It would not be the last time a writer pointed a loaded gun in my face during Texas Monthly’s first year.

In the fall of 1972, Gary Cartwright and I were making the rounds in Dallas. Gary was a journalist with a national reputation who had agreed to write a story for the first issue of a new magazine started by some young nobodies with no experience. I was the rookie editor, the nobody of nobodies. Gary was a real catch for us. If he were to write for our first issue, it would give us credibility, of which we had zero. But before Gary started writing, he wanted to put me to the test.

He took me to meet his crusty old editor at the Dallas Times Herald, who thought I was one of their copy boys. Then came the Dallas nightlife challenge. We started at the Colony Club, one of the classier joints on what remained of Dallas’s notorious Strip. I had a few drinks. Gary had more than a few, plus other substances, some of them legal. We met exotic dancers at various bars. They all knew Gary, as did the bartenders. Come midnight, Gary was just hitting his stride. He was in Hunter Thompson’s league as far as partying went. I was not.

Back then our per diem was $5 for food and $8 for a room. Gary, who was used to Sports Illustrated expense accounts, was not impressed. He’d arranged for us to stay in the apartment of his friend Pete Gent, so I went back there while Gary soldiered on into the Dallas night. Gent had played for the Dallas Cowboys and would soon publish a best-selling novel about life in the NFL. Like Gary, he was a substance tester, boundary pusher, and norm exploder. He was supposed to be out of town.

It was a restless night. Gent’s apartment was in the Love Field flight path. Two years earlier I’d been patrolling the jungles of Vietnam. Every two minutes or so, as I lay on Gent’s couch, a plane would come screaming into a landing. To me, each one sounded like enemy artillery fire. I had to fight the urge to yell “Incoming!” and throw myself onto the floor. I had just gotten to sleep when all the lights came on. A loaded gun was inches from my face. A very large human, under the influence of something far stronger than alcohol, was holding it.

Pete Gent.

“Who the f— are you?” he asked.

Gent thumbed the hammer back, his finger closing around the trigger. Gary was standing in the doorway. Without taking my gaze off Gent’s pinballing eyes, I spoke to Gary.

“Please. Tell him who I am.”

“You know this asshole?” Gent asked Gary.

Gary looked at me, then shook his head.

“I’ve never seen him before in my life.”

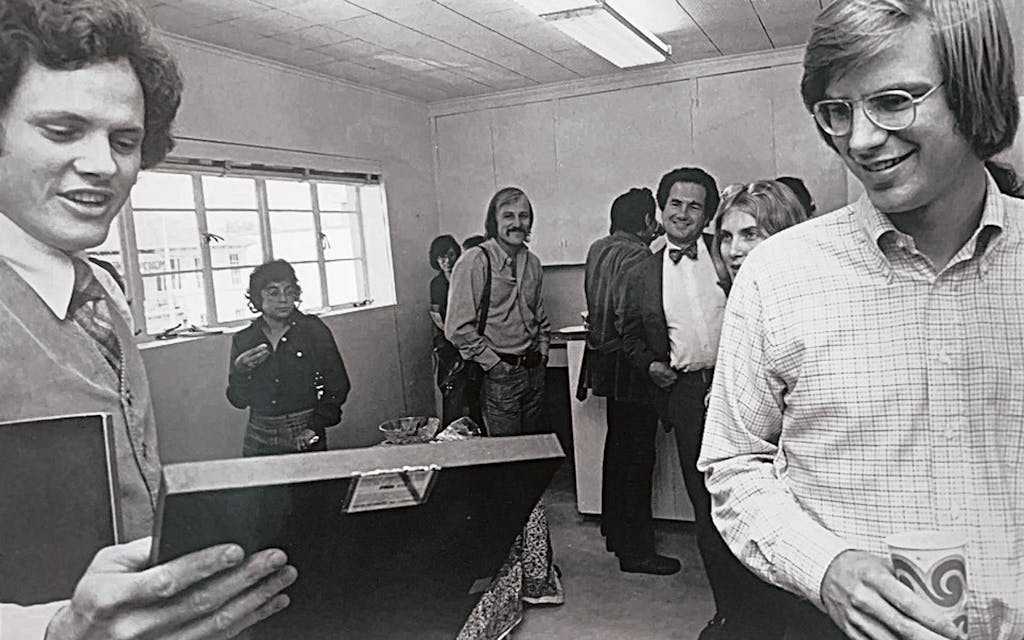

That memory comes to me while I’m reading through a bound volume of the first year of Texas Monthly. Dan Goodgame, the current editor in chief, has loaned me an office on the seventeenth floor of an elegant tower on Congress Avenue. Texas Monthly occupies the entire floor. That 1973 year was a half century ago, and we were all so young and felt like we could do anything. In those days each issue was a tightrope walk with no net. Each was a minor miracle. At some point years later, the miraculous became the normal, momentum built, the improvised became an institution, the guerrilla operation became an army. It’s all beyond what I could have imagined fifty years ago.

Trying to find the bathroom, I get lost, then lost again trying to find the kitchen, then lost again trying to get back to my temporary office. Along the way I walk down a hallway lined with the magazine’s nearly six hundred covers, arranged chronologically and mounted behind glass. I pass a state-of-the-art recording studio, where an audio team is producing a podcast episode. Texas Monthly isn’t just a magazine anymore. It’s a diversified media company with a strong online presence supported by a highly committed new owner, Randa Duncan Williams.

Over coffee in the roomy kitchen I chat with some passionate young writers. There’s a world-class energy reporter, a barbecue critic, a taco critic, a features writer. They’re creative and full of curiosity, as diverse as Texas has become—and only slightly older than we all were when we started the magazine. Across from the kitchen is a conference room that accommodates about forty people and offers a panoramic view of the Capitol. That one room feels bigger than the entire TM offices did when we started. There was nothing, then there was a magazine. How?

The answer, I think, lies in those early issues, when we built the foundation of the magazine, brick by brick—and made the bricks, too. It all started with a dream—a crazy dream, an impossible dream—in the mind of a young Dallas entrepreneur named Mike Levy. Could we make it real? If we hadn’t, none of this—the entire floor of offices, the incredible staff, the hall of

covers—would be here.

Fall 1972. Mike, Greg Curtis, Richard West, and I drove a U-Haul full of used office furniture to the corner of Fifteenth and Guadalupe, in Austin. We wrestled desks and chairs up a narrow flight of stairs to a few seedy rooms above a barbershop.

Along with Griffin Smith, who was away working his day job as a lawyer at the Legislature, that was our initial staff. We had no assistants, no art director, no photographers or illustrators. We had no typewriters yet, no Wite-out, no copy machine, no coffeepot, and no coffee. We had no schedule, no issues planned, no backlog of stories—we didn’t have any assigned. We had no writers to write them. What stories, anyway? We didn’t know. I’d been back in Texas less than a year. Greg had just driven in from California. Only Mike had worked for a magazine before, and he’d sold ads. We had no advertisers, no subscribers. In just a few months we were scheduled to go to the printer with the first issue of whatever our magazine was. We didn’t even have a name.

When we finished unloading, we sat down in our rickety chairs and took in our new home. Ants crawled up the wall. A bat fluttered in from its roost in the ceiling, which had several holes. The roof did too. Across the hall, a man who fabricated false teeth began to hammer in a slow, rhythmic manner like an Edgar Allan Poe nightmare.

The Texas Monthly creation story is an immigrant story, an American Dream story. It all starts with Mike’s father, Harry Levy. He was born in Poland and emigrated to the U.S. with his family in 1915 through Ellis Island. He moved to Dallas, went to night school, started his own plumbing business, married a young woman named Florence Friedman, and then went off to fight in World War II. Harry and Florence saved their hard-earned money to send Mike to St. Marks, the best private school in Dallas. He went on to become the first in his family to graduate from college: the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. He then worked as a freelance reporter for United Press International, sold ads for Philadelphia magazine, and earned a law degree from the University of Texas at Austin. Along the way Mike had a vision that would change all of our lives: if Philadelphia and New York could have their own magazines, why not Texas?

Once he had that vision, Mike never let it go. He studied scores of magazines, looking for how he would best run the one taking shape in his head. He worked out a budget, a business plan, a complete model for a new magazine. He first sold the idea to his parents, who backed it with their retirement savings. It was a serious amount by their standards, but considerably less than what any media company would consider adequate to start a magazine from scratch. That didn’t deter Mike one bit. He thrived on impossible challenges.

Mike would be the publisher and handle the business side. He spent months crisscrossing the state in his gray Chevy Impala, trying to find the right editor to be his partner. He carried a sample case filled with other magazines—New York, Esquire, Philadelphia—which he’d open and spread out and begin his pitch. See these magazines! We can do better than this! Texas is ripe for this! Are you in? He asked each serious candidate for a writing sample, a résumé, and a “Dear Mike” letter spelling out their plan for the magazine.

He was passionate, informed, persuasive, and driven, riding a wave of absolute conviction he had conjured up himself. After one interview, striding purposefully to his next appointment in a blinding Houston rainstorm, he walked right into a swimming pool. He interviewed some three hundred people, almost all of whom turned him down flat. It was a crazy idea, they said. He was too young, he had no experience, he didn’t have enough money, he didn’t know what he was doing. They said Texas would never support such a magazine. It would never work.

Mike pushed on. The few experienced journalists who showed some interest were, he thought, too mired in traditional journalism. So he began to look outside the box—way outside, which is how he found me. A Houston lawyer who’d been the editor of Rice University’s student newspaper gave him my name. I’d written for that paper and then had had a summer job reporting for the Houston Post before I left for graduate school at Oxford University. There I wrote a few stories for the student magazine and talked my way into being a contributor to the Economist. Along with my years as a paperboy for the Baytown Sun, that was the entirety of my journalism experience.

Mike hired me.

A few days after we moved into that shabby space above the barbershop, Harry Levy bought us some used typewriters. I put in a sheet of copy paper and typed a few words. For a moment the sound of the keys made me think we could do this. Mike walked in and looked pointedly up at the calendar marking the dwindling days till we had to ship a complete issue to the printer. Next to the calendar was the story assignment board. It was blank. My optimism vanished.

“I’m only twenty-eight. You were crazy to hire me.”

“No, you were the only one who really got my idea,” Mike said. “Everyone said that you know how to get the best out of people. And that you’d never give up.”

“What do you know, you’re only twenty-six? I was even crazier to say yes.”

“Who cares? I never give up either. That’s why it’s going to work.”

“You really believe that.”

“Yes. Don’t you?”

“Sure.”

“You scared?” Mike asked me.

“Terrified.”

“Me too.”

We looked back up at the blank assignment board.

“Well, back to work,” I said, but Mike was already out the door. He had calls to make, people to see. As it turned out, we probably would have gone bankrupt after our first six issues if our printer hadn’t forgotten to bill us. Another miracle. And here we are.

So what was my part in creating the magazine? I could say it goes back to my frontier ancestors who moved from one hardscrabble West Texas small town to another—places like Pontotoc, Rocksprings, Paint Rock, and the oxymoronic Eden, where my great-grandfather, an itinerant schoolteacher, founded the Eden Echo newspaper, which survives to this day. My mother’s great-grandparents came to Texas in a wagon in 1867. She grew up in the Montrose district in Houston. I’ve got the oil patch in my blood. My paternal grandfather worked as a surveyor in oil field boomtowns like Ranger and Breckenridge and met my grandmother while she was teaching in a one-room schoolhouse in Gordon. After World War II my father got a job at the refinery in Baytown. Our first little house had a pump jack in back. All around us oil well and refinery flares burned like Mordor.

In 1966, in the spring of my senior year at Rice, I took a creative writing class taught by Larry McMurtry. Larry was only eight years older than I was, but he’d already published two novels. The first, Horseman, Pass By, had been made into a movie called Hud, starring Paul Newman. Larry was from an even smaller Texas town than I was. In class he’d read from the new novel he was writing, The Last Picture Show. From the first lines I was in shock. You could write about high school kids in small-town Texas? I recognized all the characters. I recognized myself.

In 1971, I was just back from Vietnam and stationed at the U.S. Naval Academy. One afternoon I went to see the movie adaptation of The Last Picture Show, starring Cybill Shepherd and Jeff Bridges. The movie opens with a shot of the empty main street of Archer City. A tumbleweed blows by as the single traffic light changes. From the radio in a battered old pickup comes Hank Williams singing “Why Don’t You Love Me (Like You Used to Do).” It made me so homesick I had to choke back tears. I didn’t know what I was going to do with my life, but I knew, then and there, that I was going back to Texas.

In one of Larry’s essays he argued that we Texans had moved from frontier to city in a generation yet had not left the frontier behind. We had become, in his words, “symbolic frontiersmen.” When Mike first came to me, I didn’t yet know what the magazine would be, but I did know that it would be rooted in that mythic past yet intensely engaged with the very real present. We would get the best writers we could find to write about who we were and how we lived, stories that peered into the heart of Texas. We would tell the truth about eccentric, self-absorbed, raucous, untamed, resourceful, but never boring Texas. And we would have fun doing it.

Mike was committed to editorial independence, meaning the magazine would be free of influence from advertisers, what he called the separation of church and state. We agreed that I had to have the creative freedom to make it as good as the New Yorker, Harper’s, Esquire. It was easy to set that high bar, but how to bring it off? And what would it even be called?

Mike’s working name for the magazine was Texas Cities; his insight was that your home might be in Dallas, but you lived in Texas. The state was one big city, and the cities were its neighborhoods. Each city had local advertisers, but a Texas magazine, he believed, would be read by Texans all over the state, which would make it attractive to national advertisers as well. That was the key to his business plan.

Texas Cities was a fine name but to me it didn’t capture the full power of Mike’s vision, that ineffable quality we had of being Texan, no matter where in the state we lived. I struggled to come up with something better, then finally saw that the answer was right in front of my face. What was the new magazine about? Texas. How often would it come out? Twelve times a year.

Texas Monthly named itself.

It did not, however, staff itself. Before we moved into the new offices, it was just Mike and me, and the first issue deadline felt like it was coming up tomorrow. Mike wanted the magazine to have a core of staff writers—full-time Texas Monthly people, supported by and committed to it. The staff would be small at first, so the writers would have to be the editors too. I didn’t know a single established Texas writer or editor, so I started with people whose talent and work ethic I did know.

I called my college roommate Greg Curtis. He’d been in Larry’s writing class with me. We had spent countless late nights arguing about what made great writers great and good writers only that. He’d started the Thresher Review, a short-lived Rice literary magazine, and had gone on to get a master’s in creative writing from San Francisco State. Greg was working as a printer in San Francisco, cranking out underground comix and rock concert posters. He approached everything he loved—from boxing and pulp fiction to poker and jazz—with passion and mastery and a quirky sense of humor.

I told him I was starting a new magazine and I didn’t know if he was interested and of course if he had a good job he shouldn’t give it up, but—Greg interrupted and said he was in. He was my first hire. He did everything. He edited stories, came up with headlines and captions, and wrote humor pieces and long stories on media and true crime—a Texas Monthly trademark that he helped pioneer. He was my wingman. Greg would follow me as editor in chief, a position he held for almost twenty years, far longer than any other editor.

We would tell the truth about eccentric, self-absorbed, raucous, untamed, resourceful, but never boring Texas. And we would have fun doing it.

I tracked down Griffin Smith, who was the demanding editor at the Rice Thresher when I was a freshman and writing my first stories. Griffin was a deep and original thinker who loved European history, wine, classical music, the English language—and barbecue. Through Griffin I’d first learned that the best literary journalism could challenge every part of a writer’s education and skill. Because of his job at the Legislature he came on part time at first. For our third issue he wrote the first Best Barbecue in Texas cover story. He was one of the original architects of another TM institution dating back to 1973—the Ten Best and Ten Worst Legislators. That same year he also wrote a groundbreaking investigation of the big Houston law firms, the first of our stories that peeled back the veil on the institutions that wielded hidden power in our state. Until he went to work as a speechwriter for Jimmy Carter in 1977, Griffin was our most versatile writer and editor.

Richard West, who was Lieutenant Governor Ben Barnes’s press secretary, had been put out of work when Barnes lost the Democratic primary in the 1972 governor’s race. Richard initially came on board to sell ads, but he impressed Mike with his knowledge of the state and quickly switched to writing. The independent-minded son of the deeply conservative editorial page editor of the Dallas Morning News, Richard knew Texas. He was gregarious and indefatigable and was a voracious reader and a gifted reporter. He wrote the first Bum Steers feature and the first two Best of Texas issues.

Richard could show up in a small town like Marfa or a big-city neighborhood like Houston’s Fifth Ward that he’d never been to, and within weeks know the ins and outs as well as most lifelong residents did. He won a National Magazine Award based on his monthslong immersions in seven iconic Texas places, from the Panhandle to East Texas, from Dallas’s Highland Park to San Antonio’s West Side. Was Mike’s theory true, that for all our differences, we thought of ourselves as Texans? Richard’s stories told us, yes, we do.

Three people, that wasn’t going to do it. We needed help. Credibility, we needed even more. I admired Larry McMurtry’s contemporary Billy Lee Brammer. Billy was the author of The Gay Place, which, with its memorable main character based on LBJ, remains the greatest Texas political novel ever written. Brammer was a mysterious, elusive figure. I tracked him down chopping cedar in the then-scrubby wilds of West Lake Hills. Billy was suffering from an epic case of writer’s block. His sequel to The Gay Place lay in pieces he was unable to assemble. Would he be interested in coming on board? He would.

Billy was light-years ahead of us in terms of literary talent as well as pharmacological knowledge. The two didn’t always work together with magazine deadlines, but Billy pitched in on everything. He had great story ideas. He helped with headlines and captions. He wrote restaurant listings. He was always in the office late at night with his Hershey bars and Dr Pepper and, sometimes, cans of whipped cream that he’d spray right into his mouth. His editing was deft and unfailingly generous, and soon he overcame his writing block to do stories for us on sex and politics and the hucksters of border radio.

Sherry Kafka joined the magazine early. She was a San Antonio novelist who seemed to know most of the best Texas writers. She did the cover story for our first issue, an evocative piece about the Dallas Cowboys legend Don Meredith, who, she wrote, reminded her of the awkward boys who copied her high school papers and kissed her in the churchyard and then transformed into heroes on the football field. At the time, few, if any, women were writing about pro football. Kafka did, and with a novelist’s subtle subversion. She also wove in an inside account of how Monday Night Football, hosted by Meredith, Frank Gifford, and Howard Cosell, became a cultural phenomenon.

Brammer’s and Kafka’s participation helped give us some credibility when Greg and I met Gary Cartwright for drinks at Scholz Garten, in Austin. We were desperate to get him to write for our first issue.

“How much?” he asked.

I didn’t quite understand.

“The fee, how much?”

“Five hundred dollars,” I said.

It was an immense sum to us, but nothing like what Gary had been paid writing for national magazines.

“You say Brammer is working for you?”

“Yes, he is.”

To our astonishment, Gary accepted. We had some story ideas, but Gary had one in mind already. He wanted to write about the Cowboys’ star running back Duane Thomas, who was perplexing the team’s management because he believed that his own personal growth and dignity were more important than a fat contract or being a big star. Thomas was a complex character, a Black man given to asking questions about the value of sport and celebrity and to explaining his behavior with aphorisms of Buddhist subtlety. If we wanted Gary, it was Duane Thomas or nothing.

For all his hard living, Gary never missed a deadline, and the Duane Thomas story that he turned in was beyond anything we could have hoped for, raising issues of race and exploitation that were rarely addressed in Texas back then.

When President Kennedy was killed in 1963, Gary was living in Dallas, so when he was putting me to the test in 1972, we’d visited some of the key sites of the assassination. Gary had hung out at one of them, the Carousel Club, a seedy clip joint owned by Jack Ruby. Ruby had called Gary’s apartment the morning of the assassination to warn him and his roommate away from one of his star exotic dancers. Two days later Ruby shot Lee Harvey Oswald in the Dallas County Jail, a moment captured in a photograph that became world famous.

“What was Ruby like?” I asked Gary.

“He was a nobody who wanted to be somebody, and when his big moment came he had his back to the camera.”

I may have been a rookie, but I knew a good line when I heard one. A few years later we put that photograph on the cover to illustrate a story I asked Gary to write about Ruby. It’s still one of my favorite TM stories ever.

Gary went on to write nearly two hundred stories for Texas Monthly over the next forty years. He was constantly supportive of new writers, and mentored generations of them until he died in 2017.

The first issue was going to be 84 pages long, plus four pages for the front and back covers. Mike conjured up 27 pages of ads, though only a few of them were paid ads, including a display from the now-defunct Foley’s department store chain. Most of the rest of those pages were either public service ads, house ads for Texas Monthly, or ad space Mike had somehow traded with radio stations for free publicity. That still left us with 61 editorial pages to fill. How? Greg and I did a mock-up. Okay, table of contents. That’s one page. Maybe a column from the editor, about the issue or whatever was on my mind. Another page. Then? How about asking Mike to write a page on his vision for the magazine? He did. It was memorable. “We’re not competing with the vapid Sunday supplements with bluebonnets on their covers,” he wrote. Between us we laid down some key principles that still define Texas Monthly.

We’d also do listings of upcoming events and concise restaurant reviews, by city. If our readers found nothing else of interest in the issue, they could at least trust that we would help them find something to do.

How else would we fill the first issue’s blank pages? We decided to begin the issue like the New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town,” with unsigned shorter stories, well reported and written, that the newspapers had either missed entirely or failed to cover in depth. Brammer wrote a lovely piece about hanging out with the writer Larry L. King on the set of the film adaptation of Larry McMurtry’s novel Leaving Cheyenne. We had a piece on canoeing down the Trinity River above Dallas and Fort Worth, to chronicle its natural state before it became a flood control channel. I wrote a story about the multiracial politics of the Houston school board and another about the last speech LBJ gave, to a group of civil rights leaders. His last words were “We shall overcome.” He died the week our first issue hit the newsstands.

We balanced the two features on the Dallas Cowboys with feature stories on the rivalry of the Sakowitz and Neiman Marcus department stores (a big deal then, trust me) and the Houston consumer advocate Marvin Zindler. Richard West wrote an article on the best weekend trips, and we also had stories on the business plans of Dr Pepper and the new Dallas Theater Center. Greg did a satirical piece for the last page, which we had decided should be playful, a tradition that lasts to this day.

We promised ourselves that even if our readers didn’t always agree with us, they would be able to trust us. We planned to back up our opinions with facts, and we would double check every fact to get it right and own it if we didn’t. As it turned out Greg and I had done our own copy editing and fact-checking, and we were less than stellar at it. Throughout the Dr Pepper story we spelled it as “Dr. Pepper,” with a period. Elsewhere we said that Lockhart’s Kreuz Market lured barbecue customers in with “the smell of burning cedar logs.” In response, the owner pointed out that they only used post oak and that “If we ever burned a piece of cedar it was by mistake.” From those embarrassments were born the meticulous and relentless Texas Monthly copy editing and fact-checking departments.

Greg and I also realized we couldn’t write stories, edit them, and manage the complex flow of work at the same time. We went through a series of managing editors until we found the peerless Anne Bauer Barnstone. Alone among us on the editorial side back then, she was raising small children—which turned out to be about the best qualification our managing editor could have. Day care for adults, Anne used to call her job at the magazine, and she put the “adults” in quotation marks.

As we were working hard to get the first issue out, I was doing my best to plan ahead for the next ones. I was always looking for writers. When Mike found me, I was running the Houston Independent School District’s community relations department. A young Houston Chronicle reporter had interviewed me about a bond issue I was trying to get passed to improve the newly desegregated schools. The reporter had long hair, spoke in a distinct high voice, and seemed utterly harmless. My most outrageous and revealing quotes made it to the top of his story, which was well crafted and crackled with hidden wit at my expense. Whatever happened to that guy? It turns out he’d been arrested with a small amount of marijuana and fired. His name was Al Reinert.

That first year, Reinert wrote seven features, on everything from the best private eye in Texas to closing down the famous brothel in La Grange. He and Brammer had a lot in common—their sense of humor, their beautiful prose, their taste in drugs, and their aversion to deadlines. I remember once we were desperately waiting for Reinert’s cover story about an infamous hit man. He typically wrote in a Denny’s because they were open 24 hours. I drove to every Denny’s in town and finally found him. He’d been there through three shifts, and they’d moved a coffeepot right in front of his seat at the counter. I sat down beside him, ordered a coffee for myself, and for twenty minutes Reinert kept on writing on his legal pad. I didn’t say a word. Finally:

“How’s it going?”

Reinert shrugged and kept writing.

“Mind if I take this back and get it typeset? For the issue?”

Reinert didn’t look up, just pushed the completed pages over to me. I raced back to the office, transcribed it, edited it, ran it over to the typesetters, and edited the galleys on the spot.

That story brought us our first lawsuit. The proprietors of the Lemon Twist in Dallas said we libeled them by implying that the bar was a criminal hangout. At the deposition one of the bar’s attorneys wore gold chains and a shiny suit. Tucked into one of his cowboy boots was a bowie knife, which he’d take out at crucial moments and use to clean his fingernails. His interrogation of Reinert went something like this:

“You wrote that you learned more about organized crime hanging out at my clients’ bar than you did from reading the official crime reports. How’d you learn that?”

“From the clientele,” Reinert replied.

“What about them? Did they tell you, ‘I’m a criminal’?”

“No.”

“How then?”

“From what they looked like.”

“What did they look like?”

“Criminals.”

“Oh yeah, so what do criminals look like?”

Reinert hesitated a moment. Mike and I had told him just to stick to simple answers and, above all, don’t try to be funny.

“Pretty much like you,” he said.

They dropped the lawsuit.

Reinert also loved the space program. For our second issue he wrote about Apollo 17, the last moon mission, which launched in December 1972, just as we were finishing up the first issue. He went on to be nominated for an Academy Award for his documentary on the moon landing program, For All Mankind, which he directed, and produced with my sister, Betsy. He and I wrote the screenplay for the Ron Howard film Apollo 13. After Reinert died, in 2018, his ashes were sent into space.

I met Paul Burka in 1962, the same year I met Griffin and Greg. We all lived in the same residential college at Rice. I had wanted Paul on board at TM from the beginning, but he was working full time at the Legislature. His first contribution was to coauthor the Best and Worst Legislators feature. Paul and Griffin judged politicians not by their ideology but by their effectiveness and their character. Could they get things done? Could you trust them? If so, they had a shot at making the Best. If no, they made the Worst.

Paul was BOI, Born on the Island. Galveston. Growing up, he’d known people who’d helped rebuild Galveston after it was destroyed by the 1900 hurricane that killed thousands of people without regard for age, race, gender, income—still the deadliest natural disaster in American history. That memory informed Paul’s belief that politics should focus on how we could advance the common good and help people who’d suffered. It was a sacred calling.

For all his many talents, Paul was occasionally lacking in self-discipline about deadlines and personal appearance. Once he was even later than usual for an important editorial meeting. Everyone was waiting. I called him. Paul was a magician, skilled at making himself disappear just when his deadlines went Code Red. Surprisingly, he answered.

“Paul, where are you?”

“I can’t make it.”

“Why? You’re the key to the meeting.”

I listened to his answer and put down the phone. Everyone looked at me.

“Is he coming?” Greg asked.

“No. He says his pants are in the dryer.”

Paul became the best political writer in Texas, then branched out to write on energy and playful topics like chili, bridge, and Chevy Suburbans. Many great writers aren’t great editors, because they fall back on telling you how they would write your own story. But Paul was also a great editor, brilliant at understanding what you wanted to say and then helping you devise the simplest and clearest way to achieve it—whatever it took. Paul worked for Texas Monthly for forty years. He was the magazine’s spirit, its conscience. Paul died as I was writing this story.

Another of our early MVPs was the founder of Coronado’s Children Precision Power Mowing Team, who I booked to cut my lawn. Stephen Harrigan showed up with a crew of fellow poets. He’d already written one story for us, but at the time we couldn’t afford to pay freelancers enough for Steve to give up his yard work. His first feature was about the Children of God religious colony in Dallas. Toward the end of the story, Steve sits in a prayer circle with the Children of God and a young woman prays for him:

“Lord give Steve a safe ride back to Austin Lord show him the real reason he came here Lord God he didn’t come here for any silly article Lord you know he’ll be back Lord thank you Jesus thank you Lord.”

Then Steve ends with this:

“She says that she really loves me, and, hoping it sounds as true as I mean it to be, I tell her that I like her a lot.”

Soon Steve was writing for us regularly, and my yard never looked as good again.

Those first few years, we worked around the clock. I don’t think the lights in the office ever went out.

Over the last half century, Steve has written about the Alamo, cave diving, Galveston Bay, Comanches, and kolaches, just to name a few of his subjects. Those articles have inspired many of his books, including his recent definitive history of Texas, Big Wonderful Thing. He is one of the best, if not the best, stylists the magazine has ever published; everything he writes is informed by his compassion and his jeweler’s eye for detail.

Other longtime writers started with TM that first year. Prudence Mackintosh began by helping us out with the Dallas listings. She soon went on to do a column about raising children, then wrote cover stories and became one of our most popular writers. Mimi Swartz made her first appearance in June 1973 with a San Antonio shopping guide, but has long since been one of the best writers in Texas on everything from politics to energy to medicine. She won two National Magazine Awards for stories on health care and reproductive rights. Other great writers helped fill our pages in those early years—among them, James Fallows, John Graves, Shelby Hearon, Harry Hurt III, Nicholas Lemann, Beverly Lowry, Kathy Lowry, William C. Martin, Jan Reid, and Patricia Sharpe, who remains to this day the magazine’s authority on all matters food related.

Those first few years, we worked around the clock. I don’t think the lights in the office ever went out. We wrote by hand or on typewriters. After the first few issues, Mike got us a used IBM Selectric that was booked in two-hour increments 24 hours a day. We also got a copy machine, but Mike installed it on his desk, so whenever you went to make a copy you had to surmount his baleful stare. Meanwhile, Mike and the staff on the business side were keeping the lights on, paying for all our editorial work, and putting the magazine on a solid financial footing through what was then the worst recession since the Great Depression. Circulation began to build. By 1976 it was 200,000—and we kept growing. By November 1973 we’d had enough advertising to print 112 pages. In 1976 we passed 200 pages; two years later, 300. But that was a future we couldn’t begin to imagine right then.

It wasn’t all work. We had Texas as our playground. We were always on the road, uncovering its wonders. Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, up to the Panhandle, down to the Border, out to West Texas, over to Tyler. I wore out a set of tires in less than a year. Making phone calls for our first issue was like a comedy routine.

“Hello, this is Bill Broyles, I’m from Texas Monthly.”

“What?”

“Texas Monthly. It’s this new magazine—”

“Texas Monthly? Never heard of it. How often does it come out?”

All our distractions and our pleasures were taken in real life. There were no cellphones, no computers, no social media, no streaming services. There was no TV after midnight. Movies we saw in theaters, music we listened to live or on vinyl. We were in Austin in its magical days, and we didn’t waste them. We took meetings at Scholz’s and under the cool shade of the pecan trees at Barton Springs. We talked assignments over migas at Cisco’s on Sunday mornings. We lay on the carpet remnants at Armadillo World Headquarters with stoned hippies and cowboys and listened to Michael Martin Murphey and Jerry Jeff Walker and Willie, who’d just returned to Texas from Nashville. Austin City Limits started right after we did. Rent was cheap. The UT Tower and the Capitol were the tallest buildings in town. Freedom and possibility were in the air we breathed. Writers came. Musicians. Artists. For us small-town Texas kids, it was Paris. And paradise.

We edited the first issue’s stories and sent them to the salty old typesetters, who transformed them, letter by letter, word by word, line by line, into lead type. But a magazine isn’t just lines of type, it’s designed to be seen as well as read. We had to come up with some combination of text, headlines, and other display type that provided teasers and clues to the stories, along with photographs and illustrations that attracted the eye and deepened the reading experience—all designed in a pleasing way. It had to be done with attitude and a signature style. The Texas Monthly look.

We had an idea of what we wanted that look to be, but we had no idea how to do it. Our first issues looked amateurish, but their visual content was saved by the contributions of talented photographers and artists. For a year or two we struggled to find our design. When my then-wife Sybil Broyles and Jim Darilek started running the art department, the magazine found its look, which is not all that different from today. We had the most fun with the covers, the first impression of each issue. If someone looked at the cover and said, “I can’t believe they did that,” we’d done our job.

After all the elements of the first issue were pasted down and boxed, we raced to get it on the last bus to Dallas to make our hard deadline at the printer. If we didn’t make it, there’d be no magazine. On a few later occasions we almost missed it. Once, I sent someone to the bus depot to buy a ticket, board, and pretend to have a heart attack—so the bus would be delayed long enough for us to get our pages there.

A week later we had the first issue in our hands. We took some copies to Scholz’s to look over as we celebrated. It was so thin! Leafing through those scant pages I immediately noticed we’d left a headline off one of the short items in the front of the magazine. Damn. Mike discovered the “Dr Pepper with a period” epic fail. Gloom settled over the celebration.

“Hey, we did a magazine, come on,” I said, with more optimism than I felt.

More beer. Gloom slowly lifted. Mike left for Dallas, to try to sell more ads.

“Got to get the next issue going,” he said.

A strange look came over Greg’s face.

“What?” I asked him.

“You mean, we have to do this again?”

Back in today’s Texas Monthly offices, I closed up the volume of the first year’s issues and returned it to the shelf with dozens of others—all of them as thick as medieval Bibles. We did it again and again, fifty years on now. Six hundred issues. The “we” of Texas Monthly became hundreds of writers, editors, editorial staffers, art directors, photographers and illustrators, production people, and Mike’s whole publishing side—advertising, circulation, accounting, management. Some of them came and went; others spent their entire careers at the magazine. Month in and month out, decades in and decades out, through booms and recessions, issues fat and issues thin, they filled all those pages, they met (and bent) all those deadlines, they sold ads and managed the business, they drank and partied and picnicked together, they got married and had children and grandchildren. Many of them remain my lifelong friends. A few of them, I’ve delivered their eulogies.

We didn’t just create a magazine, we created a family.

No writer or editor or staffer meant as much to that family as my old partner Mike Levy. No Mike, no Texas Monthly. He didn’t just will his magazine into being. For 35 years he was the first one at the office, seven days a week, deluging us all with legendary Levy memos, holding everyone to the same high standards he held himself to. He was the heart of the magazine, and he wore that heart on his sleeve. Mike and I challenged each other, we laughed, we plotted, we shed not a few tears. I can’t remember a day we didn’t shout at each other.

I keep wondering why I ever agreed to join up with Mike. I mean, he was really young, and his idea was crazy. At first I turned him down. But I couldn’t stop thinking about it, so I called him back and asked him why he’d spent three years getting a law degree if all he wanted was to create a magazine. He said he needed the degree for credibility and to make him a better publisher. I thought, “This guy is serious, he’s all in. Plus it’s personal—he’s using his parents’ retirement money.” You don’t get more personal than that. With Mike, I figured there’d be no backsliding, no resting on laurels, no phoning it in. I asked myself, “Why not?” It would be fun for a few months until we ran out of money.

It all seems so mysterious to me today, how fifty years ago—in those few cramped, haunted rooms—what everyone said we couldn’t do, we did. When I asked Mike how he thought we did it, he said it was magic. Maybe so. I do know it was the most fun I’ve had in my life.

Oh, and that other time I was threatened with a gun? That was Giles Tippette, a former rodeo cowboy who did stories for us on boxers, race car drivers, and Border bullfighters. One day, he and I were arguing about some light editing I’d done to his story. Giles pulled out a Colt 38, stuck it in my face, and threatened to kill me if I changed a word. I told him if he pulled the trigger, it would be unfortunate for me and for his story too—because then it wouldn’t be published at all. Plus, prison for him, et cetera.

After a long moment, Giles handed me the gun. Yelling in frustration, he punched the wall next to my head as hard as he could. The blow left a long smear of blood. I drove Giles to an AA meeting, threw the pistol away, and published his story with the changes. The blood smear, I sprayed with clear varnish. It stayed on my office wall until we moved from our magical squalor into fine new offices in one of Austin’s first high-rises. No one ever pulled a gun on me there.

This article originally appeared in the February 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Pioneer Days.” Subscribe today.