As a photographer, I often think about time and place: exposure, people, patterns, light. And there’s no place that trains your eye to see light or prods your mind to consider time quite like West Texas, where the sun hits the open plains and jagged mountain ranges in a dependable yet dramatic way. Its rocky stretches speak of seismic moments and ages past—glacial periods, floods, inland seas, and volcanic eruptions—during which dinosaurs once roamed and the first mammals emerged from ash and began to flourish.

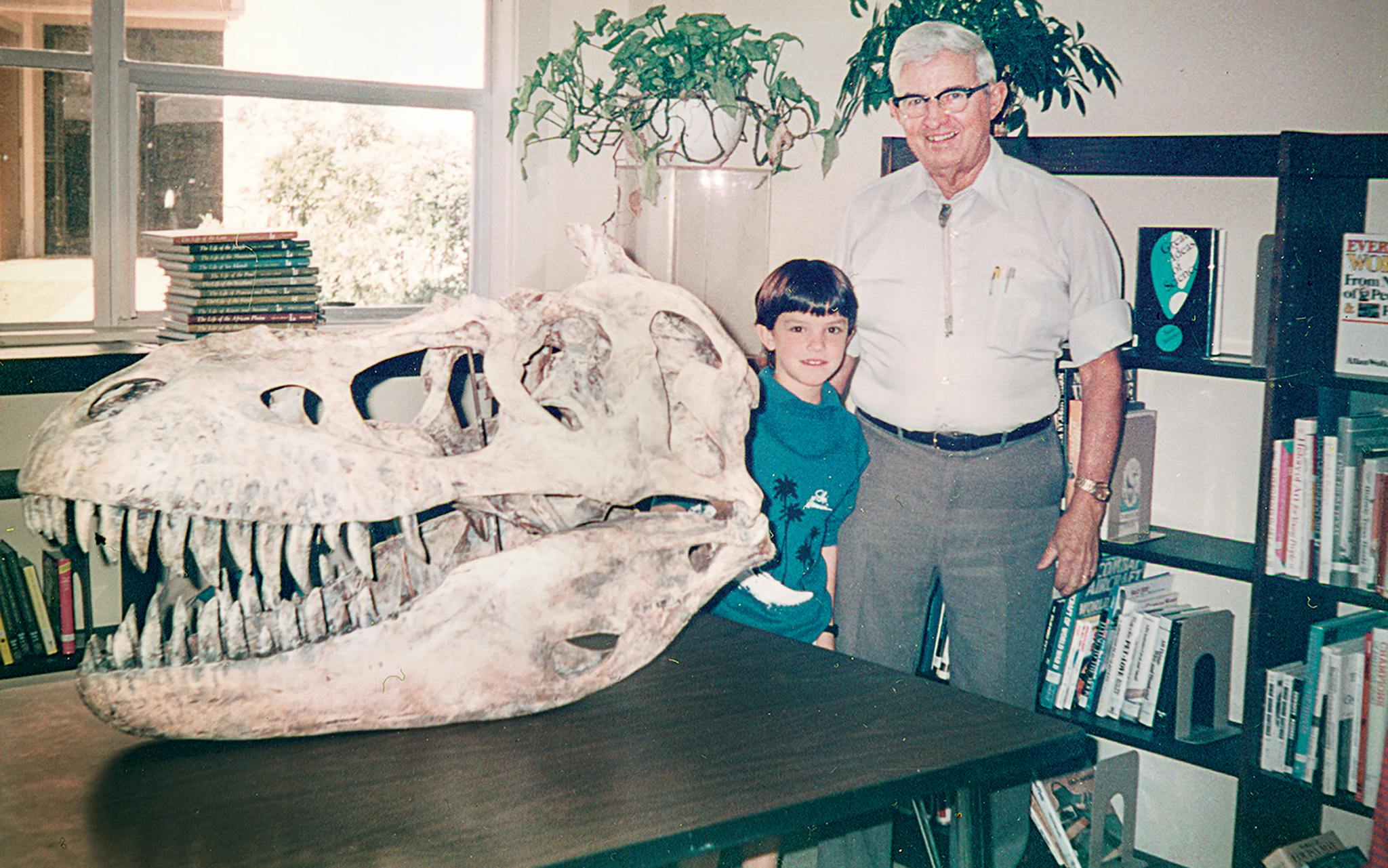

I first learned of these things from my grandfather, who was a paleontologist and was particularly devoted to the West Texas landscape and Big Bend National Park. John A. “Jack” Wilson was enamored of the area’s rocks, which date as far back as 500 million years, but it was his discovery of early mammal fossils that truly captured his attention. As a kid, most of what I knew about my grandfather’s career came from his visits for show-and-tell at my elementary school every year. He would arrive with teeth from a mammoth or the cast of a tyrannosaur skull. As my friends watched, wide-eyed, he’d bring out a measuring tape and mark out the forty-foot wingspan of the flying pterosaur, Quetzalcoatlus.

I did not fully understand his work then, or his enthusiasm for Texas dirt and its history. But several years ago, as my grandfather was reaching the end of his life, I discovered that his deep affection for West Texas and its rock formations was a passion I had come to share, a realization that set me on a personal journey to better understand his life and work. What I learned, by tracing his footsteps, is that the two of us are bound not just by love and family but also by a certain zeal for the land, a fellowship forged and cemented in the very rocks beneath our feet. This is our story.

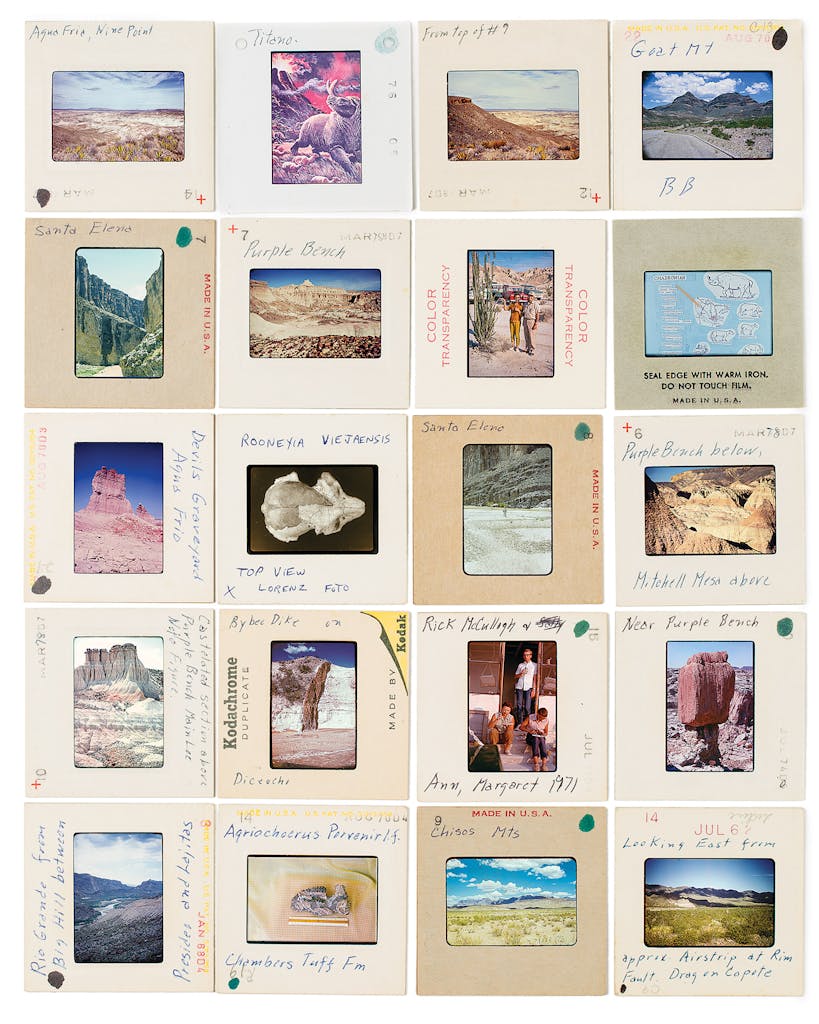

The Slides

The year before he died, my grandfather gave me three black metal boxes filled with his teaching slides. The slides featured images of geologic charts, rock formations, bone fragments and skulls, and landscapes from his annual digs in West Texas. Looking through them, I was astonished to realize that of the more than 800,000 acres that make up Big Bend National Park, my grandfather had photographed some of the exact same places that I—without knowing it—would photograph fifty years later. Yet he had documented these locations from the perspective of a scientist, while I had approached them as an artist. His interest was in the geologic formations and what might lie beneath them; I was enchanted by the color of the mountains and the way the afternoon light played across them.

The Student

Before my grandfather’s work brought him to West Texas, he was raised in the small manufacturing town of Lawrence, Massachusetts. His kindergarten teacher, Mrs. Daniels, had a rock and mineral collection in her classroom that piqued his interest in geology. Years later, as a freshman at the University of Michigan, he walked into the office of the renowned paleontologist E. C. Case. He told Case that he was interested in fossils and that he wanted to be a vertebrate paleontologist. Case replied, “Son, you’re a damned fool. When do you want to go to work?” My grandfather considered it the luckiest day of his life. In 1934, at the end of his freshman year, Case brought him along on a dig in the Panhandle. They traveled throughout the Southwest in an open-air Model A Ford wagon, looking for dinosaur bones.

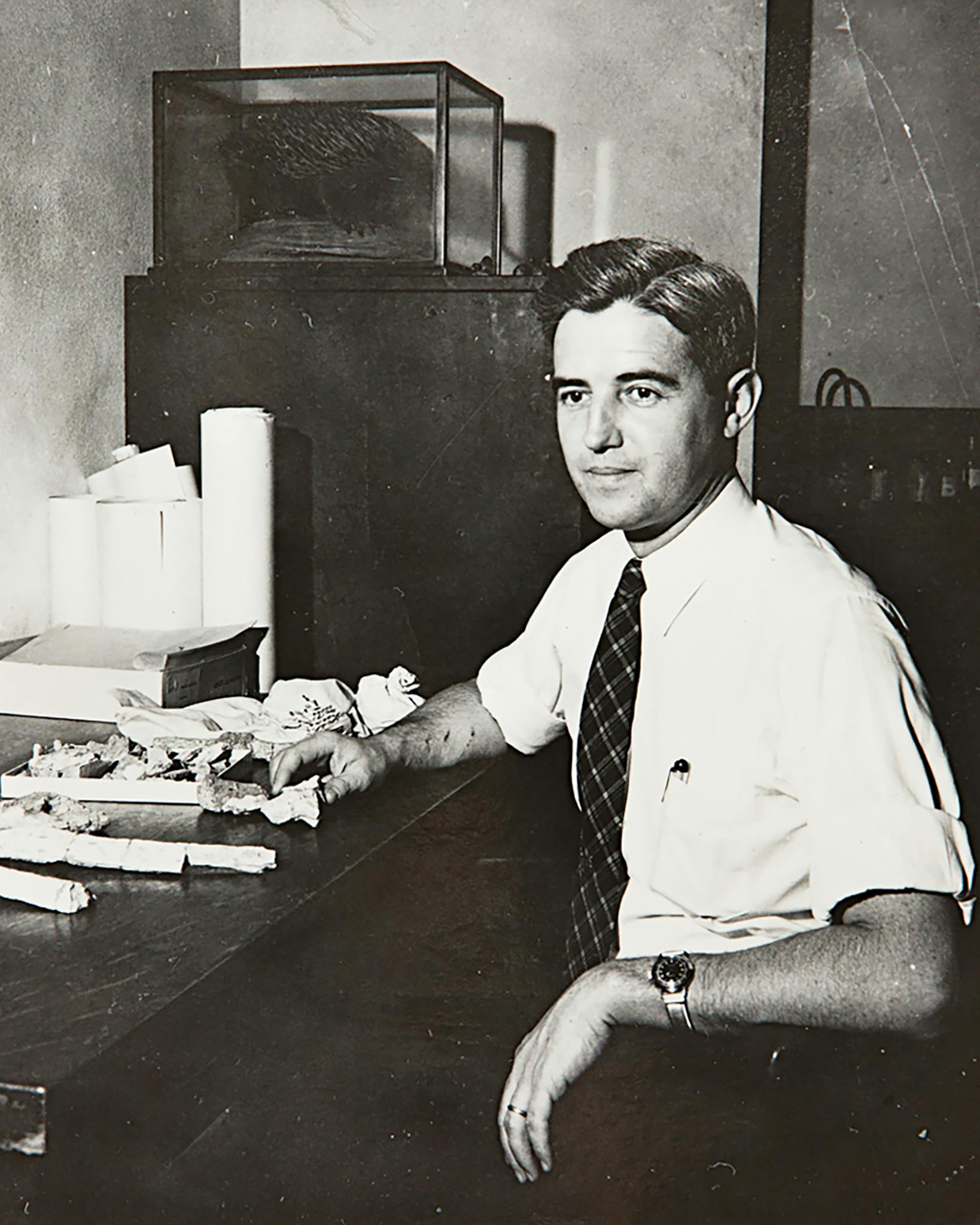

The Paleontologist

In 1938 my grandfather helped lead an expedition to northeastern Montana, where engineers had happened upon some peculiar-looking bones during a dam-building project. He and his team dug and dusted until they found the perfectly intact skull of a duck-billed dinosaur. Its entire skeleton was complete, except for its tail and one hind leg. Alive, the dinosaur would have stood 14 feet high and about 35 feet long. Excavating the bones took six weeks.

The Professor

In 1946, after serving as a signal officer in World War II and marrying my fabulous grandmother Marge, my grandfather took a teaching position in Austin, in the University of Texas’s geology department. Not long after his arrival, he began working to assemble the university’s vast collections of fossils, which for about fifty years had been scattered around different offices and labs around campus. This arduous task was not funded by UT at first, but thanks to his passion and the help of volunteers, he was able to establish the university’s Vertebrate Paleontology Lab, in 1949. There, all the fossils were cataloged and numbered, making them accessible for research and teaching purposes. In 1954 the VPL moved into a decommissioned magnesium plant in North Austin, where it remains today. My grandfather and his students would frequently add to its cache of fossils, contributing finds from their digs in West Texas every year. These pilgrimages were extremely fruitful; in the fifties my grandfather was among the first paleontologists to discover mammal fossils from the early Cenozoic era in Big Bend. He continued to lead digs long after he retired from teaching, in 1976.

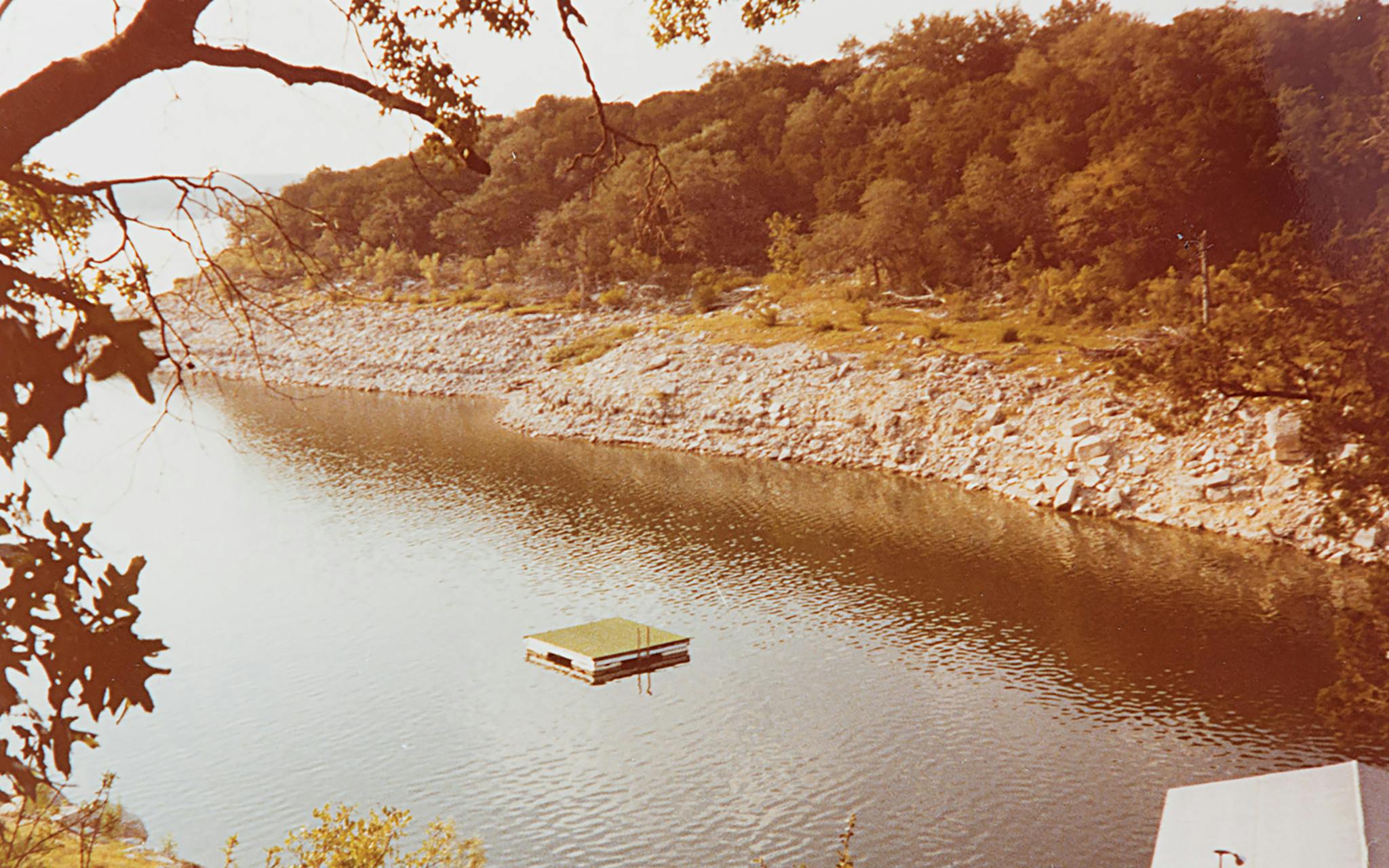

The Grandfather

As a kid growing up in the eighties, I spent many weekends and summers at my grandparents’ house on Lake Travis. I have hazy memories of being six years old, eating egg rolls my grandmother had made one afternoon and watching my parents receive a chopsticks lesson from a guest professor visiting from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, in Beijing. I remember my parents nudging me to shake hands with my grandfather’s colleagues—men like Wann Langston and Ernie Lundelius, whose names sounded so foreign and intimidating to my younger self.

The Artist

As I grew older, I didn’t make it out to the lake house as often, and my grandfather and I spent less and less time together. When I graduated from high school, in 1996, I moved to Manhattan to study photography. I loved my life in the big city, but after a few years, I was eager to head back west. I landed an internship with James H. Evans, who is a contributing photographer for Texas Monthly and whose work is a love letter to the mountains and people of West Texas. My new home was Marathon (population: 430). The town calls itself the Gateway to Big Bend, and much of my time was spent in the park. In that stark and rugged landscape, I felt as if I were the only person on the planet.

The Photograph

In 2008 my grandfather ended up in the hospital, and I went to visit him. I brought him this photograph to liven up his room. He looked so small and frail, but as soon as he saw the photograph, he brightened. He removed his respirator and smiled, then readily identified the rock formation in the photo and its exact location. In that moment, more than at any other time, I felt that the two of us were deeply connected. He died a few hours later.

The VPL

A year or so afterward, I went to the lab and saw it for the first time as an adult. It was a huge warehouse overflowing with brontothere skulls, early horse skulls, giant pterosaur bones, and mammoth skeletons. With the help of my grandfather’s former colleagues, I began to locate some of his finds. One of the lab’s jewels is this skull, Rooneyia viejaensis, which my grandfather discovered in 1964 on a ranch outside the park. As one of the most complete fossil primate skulls ever found in North America, it was the find of a lifetime. Even the paper-thin bones inside the nose survived, which is extraordinary for a roughly 38-million-year-old fossil. More than a half a century after its discovery, there is still only one known specimen of Rooneyia and no consensus about who its nearest relative is among today’s primates.

The Search

Scientists still publish papers on Rooneyia. One of them is Chris Kirk, a physical anthropologist and professor at UT. Because he too is interested in early mammals, he walks some of the same paths my grandfather once did. I met Chris one day at the lab, and the next thing I knew, I was joining him and his crew on a dig. I was never fortunate enough to go on a dig with my grandfather, but since his death, I’ve been on four—two in Big Bend National Park and two at Midwestern State University’s Dalquest Desert Research Station, also in West Texas. These digs have led me far off the trails that most visitors use. Retracing my grandfather’s steps, I now have a better understanding of how he saw the land. I can look over a stretch of pink-and-white desert and imagine a volcano that once erupted in a tropical jungle, covering all life with hot ash, crystallizing evidence of our evolutionary history under its surface. Through my camera, the mountains and rocks are no longer just pleasing compositions but almost living, breathing things, layered with the possibility of discovery. On these digs, I often find myself setting the camera down in favor of combing the hillsides for fossils.

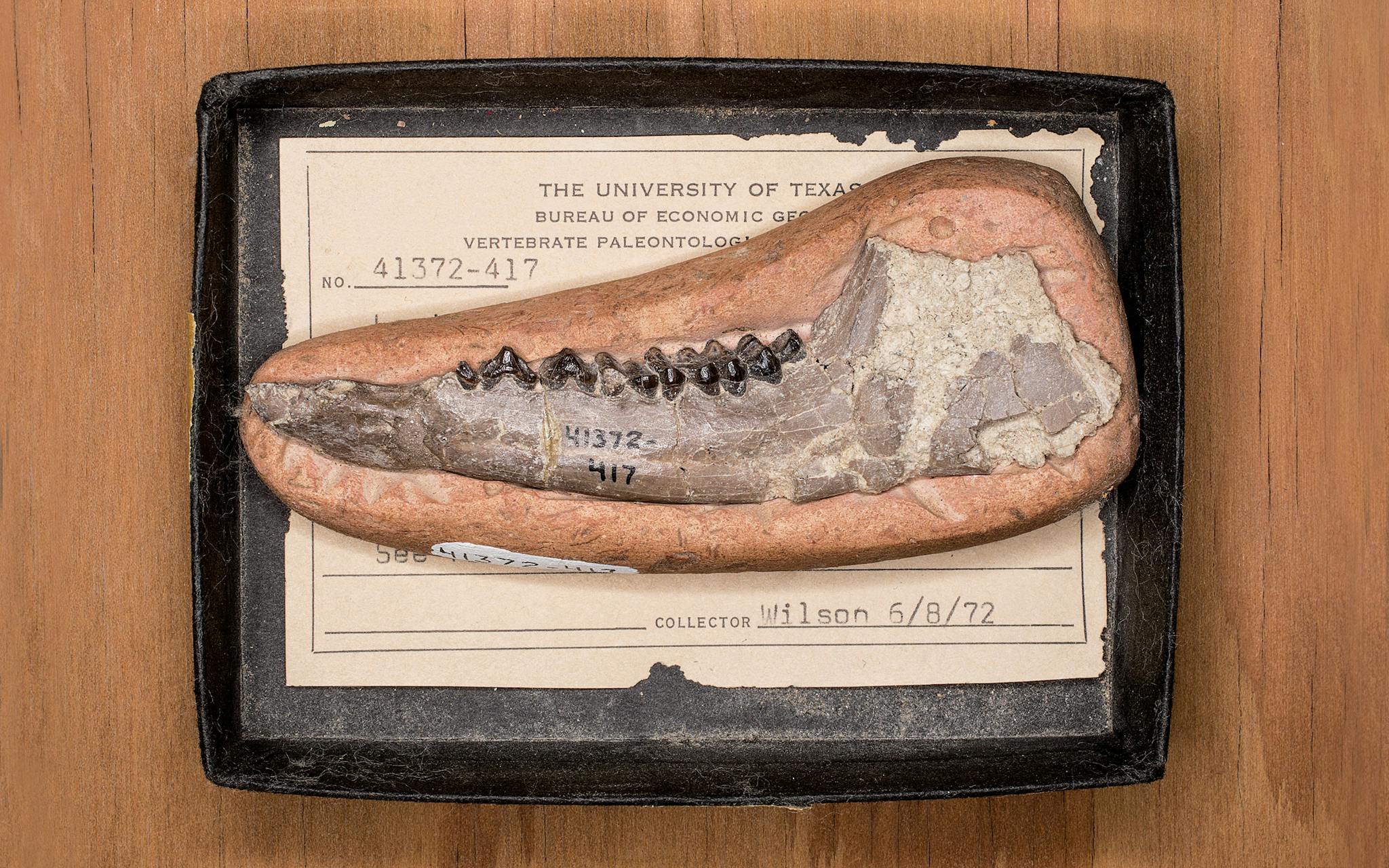

The Find

On one of my first digs, I found a piece of a jawbone with two molars that ended up being a holotype—meaning a stand-alone example of a new species, on which further descriptions will be based—of a small, early deerlike mammal that lived 43 million years ago. Finding such a specimen is rare. It was kind of a big deal, so much so that my jawbone will have the honor of being displayed in its own tiny cardboard box in one of the wooden drawers at the lab. There will be a label with a locality number, the name of the species, and the name of the collector: Sarah Wilson. It will sit right next to my grandfather’s finds from the same locality almost half a century before.

- More About:

- Photo Essay

- Marathon

- Austin