This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Someday it will happen. Maybe you’ll be trying to hunt down a parking place in Dallas’s NorthPark at Christmastime, or you’ll be fighting another traffic holocaust on Houston’s Loop 610, or you’ll be pumping gas at a San Antonio self-serve, feeling woozy from the summer heat radiating off the pavement. Then, no matter how much you like to boast of your city’s sophisticated restaurants, cultural advantages, and booming economy, a tiny thought will pop uninvited into your mind: I’ve got to get out of here.

Do not resist. Think. Think about long lines and short tempers, locked doors and open classrooms, crowded streets and empty churches, horizontal homes and vertical parking garages, too few smiles and too many smells.

There are places in Texas where the old virtues still survive, where you can leave your keys in the car or walk anywhere at midnight. Though Texas has more metropolitan areas than any other state, it still has an ample supply of unspoiled small towns. I toured the state looking for the best of them, taking as my only stipulation that the population had to fall between 1000 and 10,000. The five I chose—Alpine, Fredericksburg, Navasota, Shiner, and Canadian—are as different as the widely scattered parts of Texas they represent; yet all share a pride and a vigor that is unique to places where people have a sense of belonging together as a family.

Picking the best small towns is like choosing a friend. You look for trust (you can leave your house unlocked and keep your silver on display), health (the town is economically and politically vibrant, dominated neither by a doddering, closed gerontocracy nor by the vulgar rich), love for life (there are celebrations and festivals that bring history alive and make the town more than just a museum), and loyalty (as Lyndon Johnson used to say, “They know when you’re sick and they care when you die”).

So much for sociology. I have my own personal criteria for small-town greatness. A view and fine scenery. At least one cafe that serves good gossip along with hearty staples. A lively newspaper that acts as the conscience of the community. An enthusiastic church choir and a dramatic preacher. A good library. Air you can breathe and water you can drink without worrying about chemical content. An honest mechanic. And a maximum of three minutes to cross town.

So go now, before it’s too late, for more and more Texans are discovering small towns—or rediscovering them, really, for Texas only recently became an urban state. In the early seventies rural counties actually grew faster than urban counties, the first time in our century when that was the case. But many of the refugees moved only to the far fringes of the metropolis—Montgomery and Fort Bend counties, near Houston; Collin County, near Dallas; Comal County, near San Antonio—and now they’re being swallowed up again. They should have known better than to seek their utopia in the suburbs. Back in 1855 a small band of French Utopians established a commune on the upper Trinity River. The only trace of it today is the name—La Réunion, which survives as Reunion Plaza, a high-toned development in downtown Dallas.

Fredericksburg

Der paradise

“My family has lived in Fredericksburg for three generations. I’ve thought about moving away a couple of times, but I wanted my children to grow up here, to go to school here. I wanted them to have the same kind of background I’ve had, the same kind of values—a down-to-earth attitude.”

Elroy Behrends

Estimator

Cox Restorations

Fredericksburg

Last year what might be the state’s most perfect small town—Fredericksburg (population: 5684)—got a glimpse of one of the perils of modern urban life: the power failure. For 21 minutes this Hill Country village remained in darkness while Lower Colorado River authority officials tried to find out what had turned off the lights. An inspector with a flashlight finally spotted the culprit—a four-and-a-half-foot snake that had shorted out the circuit switches (and electrocuted itself) as it tried to reach a bird’s nest. A hungry snake and a few stolen posthole-diggers are just about the only problems in this beautiful museum-town that would please the pickiest utopian planner.

Fredericksburg is almost surfeited with excellence. Begin with the mile-long Main Street. The original plans called for it to be wide enough for an ox-drawn wagon to turn around without touching curbs, and it is. Restored century-old limestone buildings line the street—beer gardens, cafes, antique shops, and museums, as well as small-town Texas’ most beautiful library, the McDermott Building, constructed in 1882. It was once the courthouse. Half a block east stands the Vereins-Kirche (“community church”), an eight-sided structure erected in 1847 that was the town’s first public building. It is now being renovated by the Gillespie County Historical Society to house the society’s archives and local history collection. More kudos: not only does Fredericksburg have two competing newspapers, something many huge cities don’t offer, but one of them, Arthur Kowert’s Standard, won the 1979 Texas Press Association’s General Excellence Award. And, yes, the Fredericksburg High School band won first place in last year’s Interscholastic League marching finals.

Few Texas communities capitalize on their ethnic history as much as Fredericksburg. The whole town is a celebration of German architecture, drinking habits, apparel, religion, cuisine, and festivals. There are so many historic buildings that the chamber of commerce offers an auto tour lasting almost an hour. And the endless array of festivals guarantees a periodic cessation of work: the Easter Fires Pageant, “A Night in Old Fredericksburg,” the Walk Fest, the Schuetzenfest, the Saengerfest, the oldest county fair in Texas, horse racing, rodeos, and a peach festival. Gillespie County leads the state in producing nature’s foremost fruit and touts the coming bounty with a peach blossom tour in mid-March, two months before the clingstones and freestones appear.

Finding fault with Fredericksburg isn’t easy unless you harbor an obsessive hatred of antiques or businesses that have names beginning with “Der,” or unless it bothers you that Dietz’s Bakery bakes just enough of its perfect dark rye bread for local customers and is usually closed by eleven in the morning. (The owners wouldn’t bake more bread for money if it was the law.) But city fathers like Ray Fulks, head of the chamber of commerce’s industrial expansion committee and president of the First National Bank, know that the type of steady economic growth that Fredericksburg has experienced since the Johnson presidency cannot depend on visitors to the nearby LBJ ranch or urban weekenders who buy a few goods and leave. Both place heavy demands on local services such as parks and hospitals without spending much money in the community. But Fredericksburg is blessed. No one is predicting lights out here unless another hungry snake rejects the chicken-fried steak at Andy’s Diner in favor of bird’s nest soup at the power station.

Alpine

High heaven

Some towns—Longview comes to mind—never live up to their names. Alpine does: miles of unlimited vistas of the nation’s largest county; nourishing air that is never tinged with the gray of pollutants and that carries a faint chill even on sunny summer mornings; rock-jumbled mountains that encircle the town; shimmering sunlight the color of champagne; and the absence of the great noise of modern life, except for an occasional passing train. In Texas, only the nearby small-town settings of Marfa and Fort Davis offer the same kind of space, beauty, and splendid isolation. Alpine’s greatness derives not only from its magnificent scenery but also from its spirit of self-reliance and independence, supported by occasional fiscal help from Uncle Sam.

When increased costs and inflation threatened to change the bottom line of the Big Bend Memorial Hospital ledger from black to red, the directors talked about having to create a hospital district or lease the local hospital to an outside corporation. Both ideas were unacceptable to most Alpiners, so they staged a weekend High Country Hospital Roundup to raise money. One cattle drive, auction, dance, barbecue, and garage sale later, the hospital had $68,000. One ol’ boy even offered to paint the hospital’s parking lot stripes. In another civic gesture, Wilbur and Eileen Bentley decided someone ought to greet Amtrak passengers at the train station, so twice a week they shake hands and howdy visitors, offering them the unofficial Bentley taxi service if they need transportation.

The Alpine Avalanche contains one of the most vigorous letters to the editor sections of any newspaper in Texas. One man, Dr. W. E. Lockhart, had at least one letter printed each week for 54 straight weeks, suggesting, complimenting, complaining, and commenting on everything from politics to unleashed dogs. Many other letters complained about the town’s trashy appearance. Soon the chamber of commerce organized Alpine Cleanup Day; over a hundred people showed up with 28 pickups and cleaned the town from can to can’t. “More culture,” someone wrote to the Avalanche. Alpine already had the Alpine Regional Guitar Choir, the Theatre of the Big Bend, a fifty-voice Big Bend Community Choir, a chamber orchestra, and various Sul Ross University aggregations, but that was not enough for this town of 6162. So one evening last spring the curtain rose on Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

City leaders want to expand the economic base by attracting a textile or electronics plant that would hire local citizens and college students, as Midland-Odessa’s Texas Instruments facility does. Soon some company will discover the unspoiled beauty of Alpine and once again we will witness the kind of movement that helped build the nation in the last century: technology will come to the frontier, fusing the metropolis’s organizing capacity, risk capital, and sense of power with the hinterland’s self-reliance, democratic informality, and courage.

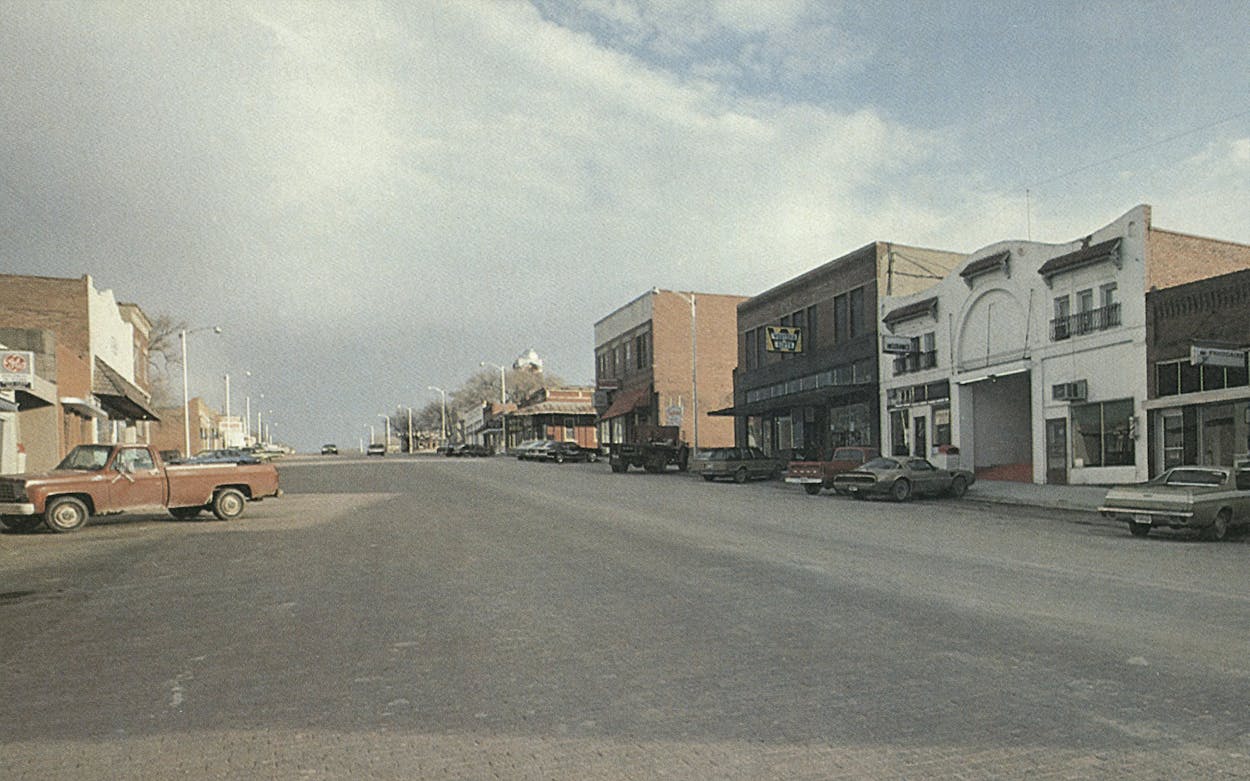

Canadian

Doing swimmingly

Canadianites were incensed when the city’s new three-tiered swimming pool opened with entrance fees that rivaled (and in one instance surpassed) those at the Amarillo Country Club. Unlike swimmers in most Panhandle towns, those in Canadian do have options. Lake Marvin is ten miles east; the Canadian River, for which the city is named, flows west to east just north of town; and there is almost always water in Red Deer Creek and the Washita River to the south. But all that made no difference. It was simply an outrage to pay so much for fun. Soon angry citizens followed the advice of editor Ben Ezzell in the Canadian Record and presented a petition with nearly two hundred firm signatures to a cowed city council. The swimming pool fees were lowered. Once again the strength of Canadian vox populi had been proved, as it had before in battles over leash laws, traffic control, and getting a light attached to an abandoned television tower.

People power is only one of the reasons that this northeastern Panhandle town of 3090 is unique. Canadian is one of the few small Panhandle communities whose status won’t change from small town to ghost town when the Ogallala Aquifer, the underground water source for much of the region, runs dry in twenty years or so. In some western Panhandle towns, such as Tulia and Plainview, growth is threatened by dwindling water supplies, but Canadian has healthy water wells and those rarest of Panhandle geographical features: surface water and hills. Unlike neighboring Ochiltree County, one of the chief breadbasket counties in Texas, only 70,000 acres out of 900 square miles in Hemphill County are devoted to growing wheat. The rest of the land is rugged draws and mesas of the Canadian River Breaks—terrain that’s useless for crops but just fine for oil and gas. Twenty-five miles southeast of Canadian is the largest natural gas well in the world, part of the Anadarko Basin, where drilling companies spent $60 million last year drilling 115 oil and gas wells, only 20 of them dry holes.

So it seemed natural to dig deeper than wheat-seedling depth to help cure the $50,000 annual deficit incurred by the Edward Abraham Memorial Home, a community-owned old-age institution managed by the chamber of commerce. A well—the Edward Abraham Memorial Well Number One—was drilled on 276 acres whose mineral rights had been deeded to the city by local property owners. It came in, and now the nursing home has an income of $100,000 a year to help pay its bills.

Canadian knows something about having its future threatened. It happened overnight in 1953 when the Santa Fe Railroad suddenly transferred a hundred families away from the line’s roundhouse-turnaround operation in Canadian, leaving businesses in trouble, bank assets tumbling, and over seventy vacant houses. That was when the city’s unique natural asset, the Abraham family, rode to the rescue—organizing fund drives, working to attract industry, and rallying the spirit of the citizens to save their town. The Abraham clan arrived from Lebanon in 1913 and eventually amassed a fortune in real estate and oil and gas. Recently Malouf (Oofie) Abraham, a former mayor and state representative, donated $200,000 for a city endowment fund. If the city matched it, he promised, he would throw in another $100,000. The city came close—$175,000—and Oofie forked over his bonus anyway.

The Abrahams also renovated the seventy-year-old Moody Hotel into a spiffy office building whose most important occupant is the Coffee Shop, the town’s chat-and-chew headquarters. Old-timers lament the passing of the Killarney Cafe, the classic small-town eatery where retailers, roughnecks, ranchers, and professional gossips gathered to meet, eat, belch, resolute, and adjourn. Now the cafe crowd divides its time among the drugstores in the two shopping centers, motel sidecars like the Vic Mon Restaurant, and more serious, get-down refueling spots like the Sage Restaurant and Private Club. The Coffee Shop, however, is the favorite, probably because of the Irish co-owner, Donna Campillo, and her French husband, who serve breakfast, lunch, and snappy patter to the locals.

Canadian does have its problems, though. Streets remain unpaved; housing is available only if you bring your mobile home; the city still has to find a way to meet the demand for electricity, having outgrown the small power plant; and the Record continues to rail away about the slipshod landscaping at Jackson Park and the miserly sum the city allocates for the library. Canadian’s greatness, and its beauty, are derived from the ruggedness of the surrounding mesas and from the character of its people. There is no soft lushness here. The town and its people will always get by, sometimes even flourish, with true grit and spare parts.

Navasota

Born again

Every other day, not long before the lunch hour, a grossly overweight old woman drives her pre–Korean War Ford to a supermarket not far from Navasota’s main street. Parking near the front door, she blasts her horn and a young man hurries out, bringing to her car the order she has previously placed by phone. Curbside grocery shopping is only one of the appealing small-town civilities that still mark life in Navasota. Despite a recent influx of industries, the rural gesture survives and the quality of life remains high. It has been said that a small town ceases to be small as soon as the continuing presence of a stranger isn’t investigated. As I checked into a motel at the end of my first day in the community, the clerk thanked me for selecting Navasota as a great small town.

Thirty years ago Navasota was slowly rotting away like the abandoned cotton fields that surround the 124-year-old town. King Cotton, the agricultural mainstay of many East Texas counties, had moved west to the irrigated lands of the South Plains near Lubbock. An era was over and the fifteen cotton gins the county claimed in 1947 had all closed. Farmers and other residents left with the cotton and kept leaving for twenty more years until in 1970 Grimes County’s population was 11,000, less than half that of 1900.

In the fifties local business officials, eager to reverse the area’s economic misfortunes, created the Navasota Industrial Foundation, but twenty years passed before Navasota’s 281-acre industrial park consistently attracted new industry. Everyone tried to help, including a high school typing class that wrote two thousand letters to companies around the nation telling of Navasota’s virtues: water, plenty of labor, good schools, wooded countryside, good soil, and nearby rivers and state parks. Finally industry responded, and now seventeen companies employing about 1400 people produce everything from cheese to mobile homes to corrugated steel culverts. Today the city’s estimated population is 5000, up 1000 from 1970.

One thing that distinguishes a great small town from an also-ran is a newspaper like the Navasota Examiner, one of the best small-town papers in the state. It fosters a sense of community, acts as a reliable grapevine, promotes civic projects, and serves as an indispensable weapon for keeping local officials honest. “We certainly feel free both to boost our town and to criticize,” said Bob Whitten, managing editor and owner. “People didn’t think the police department did anything. That’s why we began publishing everything they did, no matter how small. My wife says that’s the best reading in the paper.” Navasota has proved that a small town can avoid death by carefully diversifying its economic base while still serving as a repository of traditional rural values and face-to-face quality of life.

“It’s so nice to know the people you deal with, to breathe the fresh, clean air, to be home in five minutes at the end of the day.”

Artie Davis

Mayor, Navasota

Shiner

Beer and baseball

Early each spring, in the green, rolling country between Gonzales and Hallettsville, many of Shiner’s 1917 citizens gather at Green-Dickson Park with tractors, tillers, hoes, rakes, and trash bags to clear away the ravages of fall and winter from the park’s four baseball diamonds. Baseball is one of two passions in Shiner. Any night of the week the stands will be full of fans cheering the home team—teams, actually: one from the teenage league, two from the high schools, and two from the South Central Texas amateur league, plus Little League and sandlot teams. The other passion is drinking the beer that bears the town’s name and is brewed at the Spoetzl Brewery just north of Main Street. Founded in 1909, the brewery has operated continuously ever since, even during Prohibition, when near beer and ice sales kept the cash register ringing.

“I’ve lived in Shiner all my life—I’m 62 years old. And I’ve worked at the brewery for 26 years, done all kinds of different jobs here. I wouldn’t want to live in the city—there’s too much traffic, too much noise. No, that’s why I stay in Shiner, because it’s a small town.

“It’s kind of hard to explain just exactly why I like it here. There’s just a whole lot of things. There’s always something going on around here: big polka dances, movies over at the movie house, going fishing all the time. Yes, just a whole lot of things.”

Charles Kreming

Maintenance man

Spoetzl Brewery

Shiner

It is an easy town to get to know. Just drop by the brewery’s hospitality room during serving hours, order a free Shiner, and listen. The first thing I learned: of those pictured in the large mural behind the bar—the late owner, Kosmas Spoetzl, and a row of townspeople—the only one still alive was the man carrying the HOT TAMALES sign. The next thing I learned was the identity of the current “Eyes of Shiner.” Each week the Shiner Gazette runs a photo of a pair of eyes belonging to the head of a Shiner citizen. The person correctly identifying the mystery eyes wins two free tickets to the movie theater over in Yoakum.

Occasionally, Shiner’s celebrity, Carroll Sembera, drops by to visit with the group of quaffers, most of whom are terminally portly and fairly bursting out of their overalls. Sembera, a Shiner High School graduate, once pitched for the Houston Astros (1965–67) and the Montreal Expos (1969–70) and now is the ace of the Shiner Clippers. He also owns the town’s most popular beer-and-pool watering hole, the Tenth Inning, where the younger crowd meets after cruising along Avenue E from Saint Paul High School on the east, near the beautiful Sts. Cyril and Methodius Catholic Church, to Shiner High on the west.

“Young married folks who grew up here are coming back because of big-city pressures and because it’s easy to visit Austin, San Antonio, and Houston from Shiner. But I think being closely involved with the community is what’s most important to the people I know,” said Bobby Strauss, who came back to help run the family-owned Gazette.

The German-Czech heritage of Shiner is evident not only from its beer-drinking festivals, Lutheran and Catholic churches, and retailers like Joseph Patek, local oompah orchestra leader and grocer, but also by its fiscal conservatism. The city didn’t begin construction of a badly needed waste disposal plant until the entire $350,000 required for the project had been raised, none of it from outside sources. The Shiner Hospital Foundation, where the town’s three doctor brothers—Pat, Dennis, and Robert Wagner—practice, is a nonprofit organization that gets no funds from city, county, or state governments.

Shiner is located in an area where there are more near-great small towns than anywhere in Texas: Gonzales, Hallettsville, Yoakum, Schulenburg. All the others have to do to qualify is build a brewery and a few more baseball diamonds.

Near Misses

Utopias that could have been or once were

Sudden change is merciless. In the city a new freeway splits neighborhoods; a new building offends every eye within miles; a new industry tortures the nostrils with unrecognizable odors; a new development spoils a private memory. But when change comes to a small town it can be even more devastating. Two places that only a decade ago would have been high on the list of Best Small Towns are today struggling with the same sorts of miseries that afflict city folk.

Athens still has a lot going for it: a bucolic location on the edge of the Piney

Woods, one of the state’s oldest small-town junior colleges (Henderson County), the best small-town celebration in Texas (Black-eyed Pea Festival), and a proud political tradition as a racially tolerant and populist community. People there still look down their noses at oil-money-conscious Tyler 36 miles to the east. But the Golden Age of this Athens came to an end when the town was discovered by Dallas refugees seeking the country life. Population is climbing—37 per cent in eight years—and so are crime, traffic accidents, and unemployment. A serious vacuum of leadership has left the city unable to cope with change.

A similar fate has befallen Granbury, home of the most princely town square in Texas. There both the Nutt House (a boardinghouse reopened as a hotel) and the opera house have been restored and are flourishing. Unfortunately, the local citizens are powerless to restore the days when Fort Worth, only 37 miles to the northeast, wasn’t threatening to turn their rural county into a suburb. The main attraction for city dwellers is Lake Granbury, which has enhanced the town’s already beautiful location. But the growing population has overburdened the town’s groundwater supply, and the man-made lake is too salty to use. The newcomers around the lake feud constantly with the old-timers in town, known as “Square people.” And Fort Worth continues to encroach on the countryside.

To survive in the penumbra of a big city, a town has to be so close-knit that outsiders don’t feel wanted. That’s why Castroville, only 17 miles west of San Antonio, has been able to retain its identity. This is Alsace in Texas, with a Hill Country setting in the Medina River Valley that rivals anything the Vosges range has to offer. The whole town is a museum. There’s an automobile tour, the Landmark Inn (currently being restored by the Parks and Wildlife Department), and one of the state’s best bakeries. The trouble is, Castroville is a great place for Alsatians but not for anyone else: it is not a town that welcomes outsiders. But if it did, could it stay the same?

Other towns that rank high among my personal favorites but didn’t make the cut: Jacksonville and Palestine (great towns, but no longer small); Woodville (beautiful setting deep in the Piney Woods, but, like many East Texas towns, closed to outsiders); and Floydada (which, like most High Plains towns, was eliminated because of long-range water problems). Rio Grande City in the Valley also had to be eliminated. It’s not incorporated, for one thing; for another, it’s desperately poor—but there are times I’d rather live there than any place in the world. Where else can you find three great Mexican restaurants within walking distance of each other?

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Navasota

- Fredericksburg

- Canadian

- Alpine