Perhaps nowhere in Texas do the past and present touch as in Big Bend National Park. Sometimes called “Texas’s Gift to the Nation,” the 800,000-acre West Texas wonderland might also be called Texas’s gift to paleontology. From the mighty walls of Santa Elena Canyon to the desert bluffs of the Aguja Formation, the rocks of the park teem with more than 135 million years’ worth of fossils. Lizards run across limestone beds and posture on seashells from what was once a warm, shallow ocean. Mountain lions stalk deer in arroyos of banded Cretaceous stone. And in the Chisos Mountains, the bones of massive condors lie in caves below the perches of black vultures.

Scientists have been studying this prehistoric wealth for more than a century. In 1907, a geologist carrying out a preliminary survey of the region noted the discoveries of “saurian bones.” Three decades later, after the park was formally established during the ravages of the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration sent men to dig for fossils, establishing quarries and collections that are still turning up new discoveries. Big Bend’s fossil riches attracted flamboyant collectors—such as the fur-coat-wearing, philandering discoverer of T. rex, Barnum Brown—and dedicated scientists, such as Douglas Lawson, who found the park’s iconic giant pterosaur, Quetzalcoatlus. Throughout the last three decades, paleontologists have airlifted giant dinosaur bones, uncovered new species, and discovered more about the park’s ancient ecosystems than ever before.

As those ecosystems changed through time, so did their occupants. Rising sea levels overran the center of North America 135 million years ago, flooding land from the modern Gulf of Mexico up through Canada and forming a shallow sea full of enormous reptiles and hungry fish. Around 80 million years ago, the land lifted, and the sea slowly drained out of the center of the continent and into the modern Gulf of Mexico, leaving behind bayous and floodplains patrolled by giant crocodilians, pterosaurs, and herds of dinosaurs.

That world ended in fire and darkness, after a massive asteroid struck the Gulf of Mexico some 66 million years ago, wiping out nonbird dinosaurs and the ecosystems they lived in. Over the millions of years that followed, Big Bend gave way from tropical forest to savannas, overshadowed by the volcanoes that eventually created the Chisos Mountains. Wandering these plains were such mammals as camels, saber-toothed cats, and mammoths.

Each species found in the park is remarkable in its own right. They include the largest dinosaurs and fliers to live in North America, strange mammals like tusked swamp beasts and a swift, voracious “hell pig,” and famous species like the Columbian mammoth. The history of Big Bend can be told not just in rocks but in beasts. Taken together, they help chart the changing world of Texas’s most spectacular park. Here are some of our favorite ancient animals from Big Bend. We’ve listed them in order from oldest to most recent.

Bulldog Tarpon

Scientific name: Xiphactinus (“sword ray”)

Size: Up to 20 feet long and 1,000 pounds

Age: 85 to 82 million years ago

Toward the end of the Mesozoic Era, Big Bend was covered by a warm, shallow sea. One of the primary predators in that ocean was Xiphactinus, a car-sized fish resembling a modern tarpon. (Its jutting lower jaw also lends it the nickname “bulldog tarpon.”) Originally discovered in 1870 by Joseph Leidy, the father of American paleontology, Xiphactinus fossils first turned up in Kansas and have subsequently been discovered throughout the former inland sea that stretched from Canada to the Gulf. In Big Bend, the men of the Works Progress Administration collected skull and jaw fragments, as well as vertebrae, from their quarries. While Xiphactinus wasn’t the largest marine predator in the park—that honor goes to immense sea lizards like Tylosaurus—it was a singularly voracious one, its speed and maneuverability making it an adaptable and indiscriminate hunter. Sometimes this gluttonous species had eyes bigger than its stomach: fossil remains of one Xiphactinus show that the creature died from choking on large fish.

Horned Herbivore

Scientific Name: Agujaceratops (“Horned Face from Aguja”)

Size: Up to 21 feet long and and 6,000 pounds

Age: 83 to 72 million years ago

As the oceans of Big Bend retreated, they were replaced by open, swampy deltas filled with browsing dinosaurs. Among them was Agujaceratops, an earlier relative of the more famous Triceratops, with a horned head, parrot-like beak, and heavy frill. That frill made up a third of Agujaceratops’s body length, and a fossil skull from this animal discovered in Big Bend is the largest ceratopsid skull ever found. Originally collected from the WPA quarries of 1938–1939, the remains proved to be a rare bone bed of twenty young and adults, suggesting that Agujaceratops traveled in herds. (The bone bed also suggests that their appearance—and perhaps coloration—depended on their age and sex.) While originally believed to belong to a genus of dinosaurs called Chasmosaurus, a 2006 reappraisal found that it was different enough to warrant its own name. Today, two species of Agujaceratops are known in Big Bend. Agujaceratops was the most common type of ceratopsid found in the park and is the oldest known member of its family in North America so far.

Texas Titanosaur

Scientific Name: Alamosaurus (“cottonwood lizard”)

Size: Up to 80 feet and 65,000 pounds

Age: 72 to 66 million years ago

Deltas eventually were replaced by baking floodplains stalked by giants. The biggest of them was Alamosaurus, the largest dinosaur in Cretaceous North America. Despite the name, the species wasn’t named after the Texas landmark, nor was it originally found in Texas. Its bones were first found in New Mexico back in 1921, and its discoverer named it after the Spanish word for cottonwood trees. Most long-neck dinosaurs had vanished from the continent by Alamosaurus’s time, and it appears to have been a newer immigrant from South America. A fully grown Alamosaurus was too large to worry about predators, and likely acted as an ecosystem engineer on a scale difficult to imagine today: knocking over trees, digging wells in arid environments like modern elephants, and reshaping forests and plains with its passage and droppings. These sauropods are among the last non-avian dinosaurs known to exist in Big Bend.

The Giant Wing

Scientific Name: Quetzalcoatlus (“feathered serpent god”)

Size: Up to 9 feet tall at the shoulder, with a 36-foot-long wingspan, and an estimated weight of 551 pounds

Age: 72 to 66 million years ago

In Cretaceous Big Bend, the giants didn’t just live on the ground. Soaring overhead was Quetzalcoatlus, a giant predatory pterosaur—a cousin of the dinosaurs. The species first turned up in 1971, when paleontologist Douglas A. Lawson found an enormous wing bone in the park. He and his professor, Wann Langston Jr., named the species after an Aztec god. (The species name, northropi, commemorates “Jack” Northrop, designer of the bomber and later one of the founders of drone manufacturer Northrop Grumman.) Two species of Quetzalcoatlus are known from Big Bend; the smaller, named after Lawson, is known from more than two hundred specimens found at a site called Pterodactyl Ridge. It’s not totally clear how effective a flier Quetzalcoatlus was; some researchers have suggested it was an excellent soarer, perhaps able to cross continents. Others have suggested that Quetzalcoatlus lived more like a bustard or a ground hornbill, able to undertake powered flight but spending most of its time on the ground, hunting smaller prey. (Though when you’re a giant pterosaur, “smaller prey” includes animals the size of humans.)

The Tusked Swamp Beast

Name: Titanoides (“Titanlike”)

Size: Up to 10 feet and 330 pounds

Age: 56 to 50 million years ago

After the extinction of the dinosaurs, mammals rapidly grew to take over the newly emptied landscapes of a hothouse world. Among them was Titanoides, a large bear-like animal. The lineage it belonged to has no living relatives today, and it was among the first mammals to reach genuinely large sizes. While male Titanoides had saber-like tusks in the upper jaw, the species seems to have largely been herbivorous, using its canines in territorial or mating disputes. (The Big Bend fossils of the animal include a complete skull of a tuskless female.) Titanoides seems to have been a semiaquatic browser. On such animals today, like hippos and tapirs, tusks are generally accompanied by thick layers of fat, protecting the animals from each other’s bites. The same may have been true of this strange swamp monster.

The Hell Pig

Name: Archaeotherium (“Ancient beast”)

Size: Up to 6.7 feet long and 330–520 pounds

Age: 35 to 28 million years ago

As the tropical hothouse cooled, the landscape of Big Bend became a patchwork of jungle and savanna, overlooked by towering volcanoes. One of the most bizarre hunters of this ancient Serengeti was Archaeotherium, a rather hog-like hoofed mammal. (Despite its porcine appearance, it was more closely related to hippos and whales than to modern pigs.) Bite marks on contemporary camel skeletons and caches of bones show that Archaeotherium was an active and dangerous predator. Its cheekbones and bony skull knobs may also have helped it display in dominance battles, though sometimes such posturing came to blows: one Archaeotherium skull shows healed puncture marks around the eye from another member of its species. Interestingly, young Archaeotherium do not show the extreme jaw strength of sexually mature adults, suggesting that the genus’s powerful bites may have had a role in social behavior as much as hunting—or that the animals’ diets changed as they grew. While no Archaeotherium bones are known from the park, its teeth are found in fossil deposits of the same time just outside park boundaries.

Moose Camel

Scientific Name: Leptoreodon (“slight mountain teeth”)

Size: Up to 6 feet long, weighing 40–60 pounds

Age: 35 to 28 million years ago

As the savannas extended through Big Bend, browsing forest herbivores would eventually give rise to fleet-footed runners. An early forerunner of that transition was Leptoreodon, a deerlike animal with short limbs, a moose-like snout, browser’s teeth, and a camel’s digestive system. An early member of a group of swift, deerlike animals that later evolved slingshot horns on the nose, Leptoreodon had none. Named in 1868 from fossils uncovered in Canada and Texas, three species are known from Big Bend, mostly from jaw fragments. Likely found in dense, brushy, and wet habitats, it may have been quite comfortable in and around water, like the modern moose.

Scimitar-Toothed Cat

Scientific Name: Nimravides (“nimravid-like”)

Size: Up to 6.6 feet long and 660 pounds

Age: 10 to 5 million years ago

As time passed, Big Bend became cooler and drier, the savannas giving way to drier prairies filled with toed horses and herds of camels. Stalking these prey was Nimravides, a cat related to the later, larger (and more famous) Smilodon. Nimravides’s name is a prime example of how confusing paleontology can be: it’s a reference to an earlier mammal, Nimravus, which was thought to be a relative of saber-toothed cats before researchers realized the species was closer to dogs. (Complicating things, nobody’s entirely clear on what the describer of that animal meant by the name.) Known in Big Bend from teeth, jaw, and toe materials, Nimravides’s scimitar canines were a powerful weapon for killing prey, causing massive blood loss and leading to a quick death that saved the predator from injury. But the teeth were fragile: animals that broke them on bone would have faced a lingering death from starvation. Nimravids lived in North America from the middle to the end of the Miocene prior to the invasion of more specialized saber-tooths from Asia.

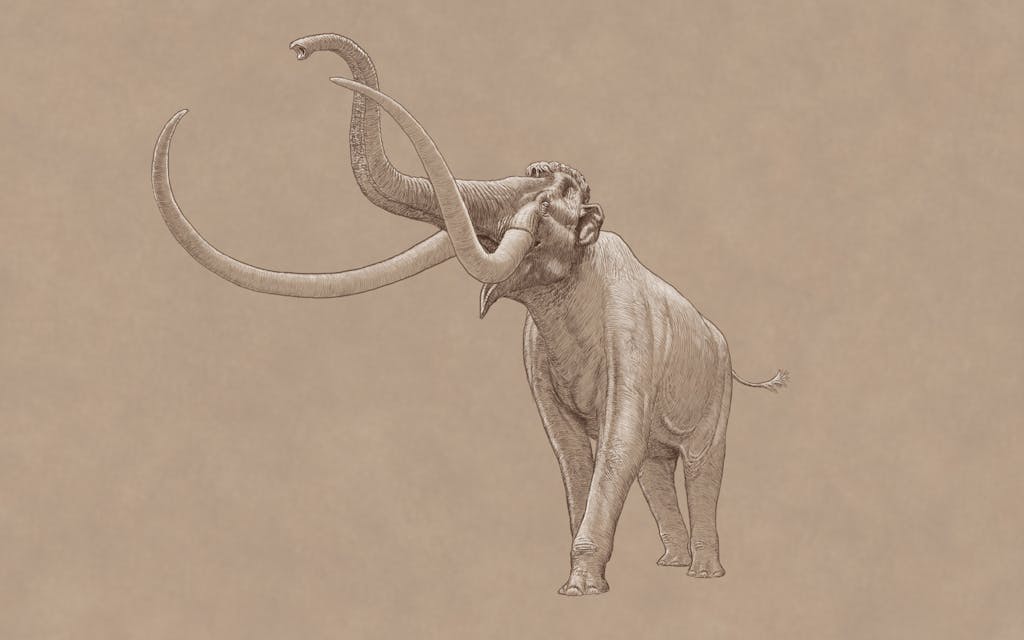

Columbian Mammoth

Scientific Name: Mammuthus columbi (Columbus’s Mammoth)

Size: Up to 13.1 feet at the shoulder and 22,000 pounds

Age: 2.59 million years ago to 11,700 years ago

Some of Big Bend’s most spectacular animals were present until almost yesterday—geologically speaking. During the Ice Age, the park was home to the Columbian mammoth, last and largest of its family and one of the most famous extinct animals in the world. Its tusks, jaws, and teeth have been found in the area: one rancher outside the park even used mammoth teeth as a boot scrape before he was alerted to its identity. The largest herbivores of their time, mammoths likely traveled between cienegas—or “desert marshes”—created by springs in the American Southwest. They coexisted for a time with America’s first humans, before disappearing at the end of the Pleistocene, likely due to some mixture of changing climates and overhunting by ancient humans.

- More About:

- Critters