This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

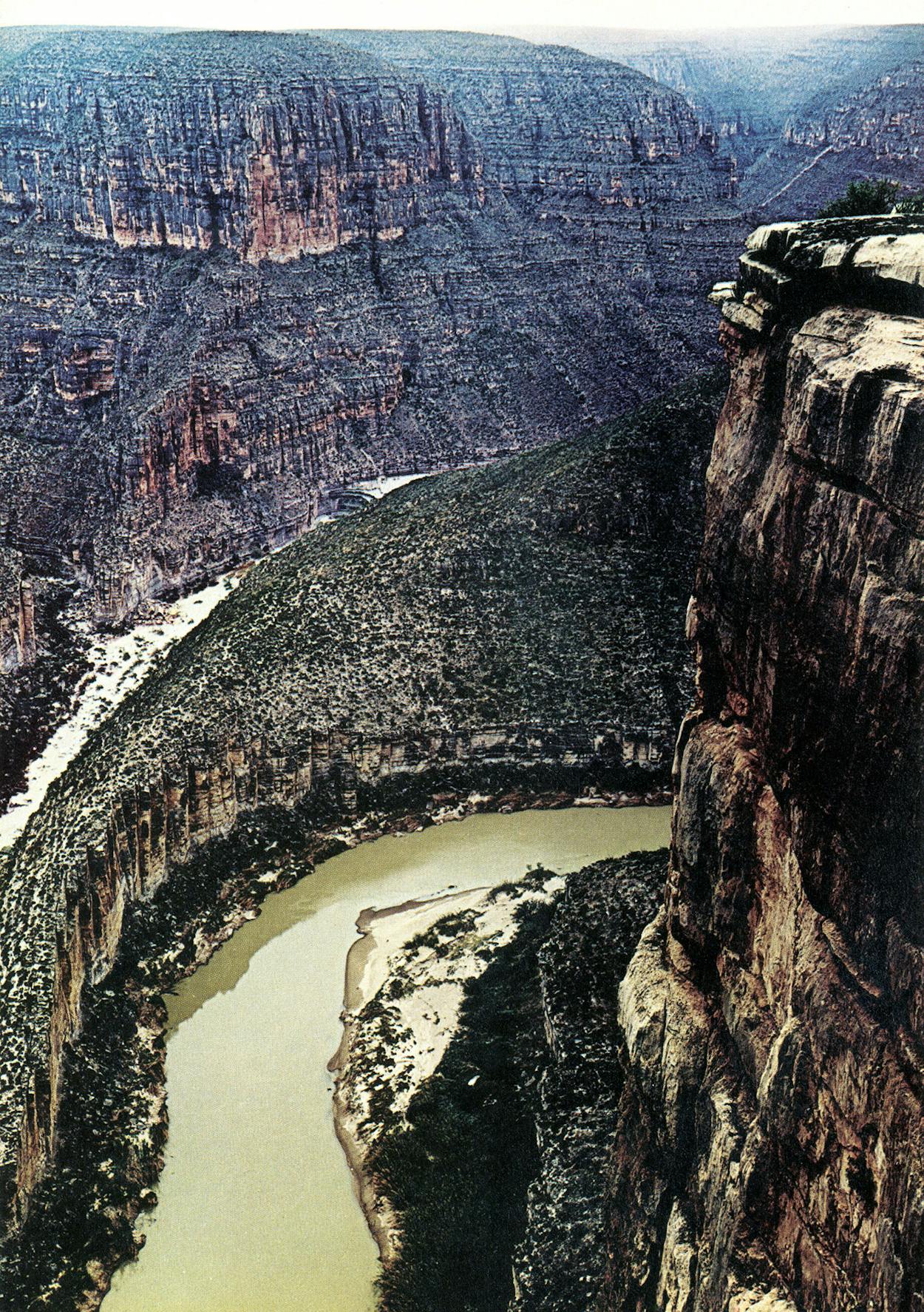

While rafting not long ago down part of the Rio Grande in the Big Bend, I learned with a shade of a disappointment that the blackish, dense, fluted, and sculptured material forming the superb high walls of Mariscal Canyon consists of Lower Cretaceous limestone partially metamorphosed toward marble by ancient heat and pressure. Not being a devout or even passably competent geological type, I don’t ordinarily get emotional about the composition of rocks. But a good many years before, I had canoed happily and ignorantly in that region with some others mainly as happy and ignorant as myself, along a stretch of the Conchos in Chihuahua to where it joins the Rio Grande at Presidio in the Big Bend, and when passing through other fine canyons sliced out of that same stone we had airily classed it as basalt. This was because it was dark and hard and sometimes shiny, but even more, I suspect, because “basalt” as a word rang richly in our ears, sounding igneous and exotically different from the prosaic limestones and sandstones and shales we were used to in our more easterly and sedimentary native habitat.

The friend who provided this mild disillusionment, Jim Bones, does not see the Lower Cretaceous as undramatic at all, and of course it isn’t, not in a haunting, otherwordly place like Mariscal Canyon. The Rio Grande, all 1885 miles of it plus some tributaries, is “his” river in a mental way that I understand, having felt thus myself in my time about a couple of other streams. The feeling comes not from deeds of title but from knowledge and caring, and it gives every stone and thorny bush and biting bug and cry in the night its full significance in the riverine scheme of things. Through informed awareness, friend Bones possesses the Rio Grande where it begins in the snowy Colorado Rockies, and where it courses clear and cold and copious through the mountain valleys and high cool deserts of the ancient Pueblo country of northern New Mexico, and in the hotter arid places south of there to El Paso and beyond, where it is often reduced to trickle or no flow at all by irrigation, evaporation, and absorption in the spongy desert soils and is replenished only when the Conchos, and later other tributaries, enter it far downstream. I think it’s most especially and belovedly his in the Big Bend, where we were taking that raft trip, a stark, lovely, forbidding jumble of deserts and canyons and crags in far West Texas. But his claim extends on past where the canyons end, or are drowned, in the upper waters of huge Lake Amistad near Del Rio, and includes the less scenic but powerfully historic final reaches where it runs through brushy rolling lands past old towns and battlefields to the tropically lush Lower Valley, discharging itself at the last into the blue Gulf just beyond the pale clean sands of Padre Island.

The Rio Grande has been a stage for explorers, revolutionaries, smugglers, and now canoeists and kayakers. Amid this procession the river remains immense, mysterious, immutable.

Insofar as most natives of this state feel propriety about the Rio Grande, it is probably in terms of this final stretch below Del Rio. Not only is that the part they see most often but it is also an international boundary imbued with the fascinated feeling that all such boundaries generate—a feeling, illusory perhaps, of distinct languages and distinct cultures and distinct breeds of people facing one another across a mere stream, or fence, or arbitrary line traversing hill and dale. Moreover, the South Texas part of the Rio Grande has had strong bearing on the flavor and directions of Texas’ past, as it still has on its present, and thus is “our” river in a basic way.

Myself, I first knew the Big River there when young, seeing it most often as a tawny flow beneath international bridges when I crossed them. Sometimes I was with college friends on feckless weekend or vacation forays that didn’t usually get past the grubby towns at the south ends of the bridges, with their promise of adventure that seldom materialized, though I guess we thought it did. Short of cash in those Depression times, we subsisted on things like street-stand goat tripe tacos at 3 cents a throw, found lodgings with corn shuck mattresses, haggled in markets over the price of straw sombreros and other gewgaws, emerged somehow unscathed late at night from side-street cantinas whose habitués sat around drinking very cheap firewater and thinking up new reasons for detesting gringos, scouted the Boys Town zona and on rare occasions did something about it but more often were scared off by impecuniousness or thoughts of disease and mayhem.

The Rio Grande was there, sluggish and turbid most of the time, but I don’t recall thinking about it as much as a river, as water, except when I envisioned, as I always did when first sighting it and often do to this day, little midnight groups of brown men wading through it up to their breasts or necks and holding bundles aloft. For wetbacks were very much with us even then, and I had worked with them on country jobs in summer and felt the pull of their language and of their grave, gentle ways. One midnight during those years in fact, I got a wet back and other parts myself when we waded out to an appointment in the river’s shallow channel near a ruined bridge somewhere, meeting a furtive fellow with an ocelot kitten in a box, unacceptable at customs, for which my college roommate handed over $6.

Just outside the more garish Gomorrahs’ commerce and fleshy joys, though, lay the real border country, a belt of dry, scrub-clad, thorny, and inhospitable land on both sides of the river, which had very little to do with fleeting weekend pleasures but held some fine, tough laconic ranch people white and brown, as well as a great deal of tangled history splattered with an astounding quantity of blood. Coahuiltecan indigenes, Spaniards, Mexicans, Comanches, Apaches, Anglo-Texans, Confederates, Yankees, and other breeds had overlapped and mingled there, and while the results had been sometimes beneficent (all readers of Webb and Dobie know, for instance, that Americans learned basic ranching and cowboy skills from Mexicans in those parts, and from there carried them up the length of the West), more often they appear to have been disastrous, if often romantic in a murderous way. I know these awarenesses have faded now, as possibly they should have, but for young Texans of my generation there were dozens of borderland names of violent places and people that rang like bells in the mind and stirred you when you went there. Roma, Mier, Camargo, Resaca de la Palma…Cheno Cortinas, Tom Green, McNelly and his Rangers, Zachary Taylor, Pancho Villa…but let them rest.

Some of us went hunting from time to time in the brushlands north of the river, for quail or dove or deer, and lucky ones got an occasional look at unchanged, almost biblical old Mexican places to the south, where practically everything was still held together with rawhide, plows were of wood and drawn by oxen, women carried water in clay vessels on their heads, and long-stirruped, casual, superbly balanced horseman used plaited hide reatas on scrub Longhorn cattle among the mesquites.

Life both human and wild was most abundant near water, and dense spiny tangles of brush near the river in its lowest part teemed with tropical beasts and birds unknown north of there. Most of that riverside thorn woodland is gone now, cleared away for irrigated farms and orchards, and with it have gone many of the creatures, including those cats—ocelot, jaguarundi—that still occurred there in my youth. Poking about with a field glass and a stock of curiosity, though, you can still find remnant thickets and in them, at the right times, chachalacas and groove-billed anis and a number of other bird species not seen elsewhere in this nation. You may find remnant shards of history too, enigmatic for the most part. Following some strange bird’s call, I once stumbled over the ruins of a thick-walled stone house where generations must have led quiet, useful, rawhide lives and where something (Indians, pestilence, outlaws, armies, flood, fire, drouth, what?) had brought it all to an end, and came afterward to a clearing where a small Mexican graveyard lay, fenced with hewn weathered slabs of mesquite, fragrant with that same tree’s bloom, and loud with the cucurucu of white-winged doves and the hum of yellow bees hived within a nineteenth-century patriarch’s cracked white-limestone tomb.

Many people feel vaguely and benevolently possessive toward one or another river or just toward rivers in general, as is pleasantly manifested in the uproar that pollution, proposals for big dams, and other threats to the well-being of running waters can sometimes awaken these days. Fewer are stirred to emphatic and particular claims of property rights such as good Jim Bones exercises in relation to the Rio Grande, which may be well for the public’s general peace of mind. It is a stout urge when it hits you, and giving in to it whole hog does not always lead to ecstasy.

For one thing, other people, troublesome as always, seldom cede you the rights of ownership, but instead catch your fish, shoot canoes down your rapids, ogle your scenery, shatter your quietnesses with portable radios, strew your sandbars with beer cans and orange peels and busted minnow buckets, and wash their sweaty torsos in the rippling, living waters you have claimed as your own. Worse, acting as individuals or corporations or bureaucracies, they may foul your river with the sewage or poisons, grab part of its flow for irrigation and give back only a shrunken muddy surplus, or impound it in reservoirs that change forever the age-old manner of its functioning, if needed they don’t dam your own stretch and wipe it out of existence. In short, if you wax too possessive toward a river you stand a good chance of ending up permanently enraged.

For another thing, a river is a complex entity, and instead of possessing it you may turn out to be possessed, even obsessed. This holds true even if you limit your interest to one facet of the river’s possibilities, as did Robert T. Hill, who mapped the Big Bend Rio Grande in 1899, battering his way through its unknown canyons with his crew in three cumbersome wooden boats, passionately in love with the river’s geography and the magnificent jagged terrain that had produced it but contemptuous of the desert with its “spiteful, repulsive vegetation” and in general of people stupid enough to choose life in such surroundings. Equally obsessive is the fascination of local historians with the local streams, the loyalty of anglers to known pools and riffles, or the single-mindedness of addicted river runners in their kayaks and canoes and rafts. On the Rio Grande and elsewhere these last are a numerous breed with whom I feel much kinship, even if they’re sometimes jealous and authoritative enough within their watery domains that a birdwatching, rather wide-ranging friend of mine says they remind her of a certain aggressive African species of river duck that takes a linear segment of stream for its own and assaults any living thing that comes there.

But broader river obsession may be worse. It derives from having a slant of mind that needs to know how things work, and it doesn’t lead to easy answers. For a river does not work by just running handsomely through its allotted landscape but rather, with its network of tributary streams, as the drainage system of a wide basin within which lie a variety of terrains and minerals and climates, all of which have bearing on what the river itself is like, as do most human activities within that basin. It works too as a small stir in water’s eternal global restlessness, which not only is vital to most of Earth’s protoplasm, including our own, but also, in conjunction with crustal upheavals and subsidences, plays a main part in shaping the planet’s surface. Whether as pounding rain and hail, mountain-gnawing frost, erosive runoff from downpours and melting snow, floods laying down gravel and silt in bottomlands and deltas, seeping underground flow, or invading seas that drop their vast thick loads of lime and clay and sand and then recede, water is primary in texturing the land. Most of visible Texas, we know, has been deposited and carved by such action, and it will keep on being thus deposited and carved and changed even if, as seems most likely, our own sort of protoplasm does not survive its brief blink of geological time to witness and study the process.

Tricked into such bottomless and somber realms of inquiry by what may have started out as simple lyric appreciation of a quantity of pretty water flowing downhill in a channel, the possessor of a river, Adam-like, has lost his innocence. It’s unlikely that thereafter he’ll look at his river, or any other, and be able merely to note (as he still will note, however, if he ever did) what birds flit in the willows and what green tongue of current might hold feeding fish and what jumble of boulders would need some fancy paddle work if one were navigating where the water churns loud among them. He’ll be queasy about the river’s well-being even when it looks fine and will find himself pondering in addition where it comes from and why and how, what all its tributaries are like along with the country they drain, what sort of life various kinds of people have managed to shape in those places, how they’ve rubbed on one another and on the river system, and all such manner of things. He has diluted his pleasure based on wonder by turning it into a quest for knowledge, and such a quest once started seldom has an end.

Pleasure based on wonder is pretty nice stuff, though, and I find with gratification that in relation to waters like the Rio Grande, together with the Conchos, Pecos, Devil’s, and San Juan rivers that feed it, I can still keep a little wonder going. I am not inwardly compelled to learn all that I can about them, even though I do feel a sort of ownership in certain spots and areas and stretches along them that I’ve known passingly or fairly well.

One such place is the mountain country of northern New Mexico, which holds the snowy sources of the Pecos and lies not far below the high part of Colorado where the Rio Grande is born. Most of us, I believe, think of rivers as arising in mountain wilderness and flowing down through more wilderness to find civilization in lowlands and near the sea. But while there is some fine wild scenic ruggedness in that section, the Big River itself has contact with civilized folk almost from the very start, being used for irrigation within a few miles of its source near Creede and then dropping down to lands where Pueblo Indians maintained a high level of culture for many centuries before Spaniards arrived to take things over. Both Pueblos and Latins shaped rather tranquil and graceful lives there, bloodied a bit at times by conflict between them and by jealous incursions of Navahos and Apaches, and outland gringos in later years have sought to take that tranquility unto themselves, sometimes shattering it in the attempt.

That presence of appreciative and often quite literate outsiders in Santa Fe and Taos and other favored spots has produced a good many expert interpreters of the region, and I am in no sense one of them. But I learned to fish for trout there long ago, after the Second War, and once spent an agreeably lonesome six months in a cabin in a creek flowing to the Pecos, a high, fresh, sparsely peopled place. Sometimes I sought larger quarry in the Pecos, or I would drive to the Rio Grande itself, below where it left its gorge near Taos. I remember wading and fishing on a quiet evening there when caddis flies were thick on the water and above it, and trout were striking at them from below while bats and violet-green swallows devoured them in the air, swooping at times beneath my elbows as I cast.

There is no fishing like that in the river’s flat hot desert reaches lower down in New Mexico where the desert air and soils work their subtractive magic on its snow-fed flow, the land where in Spanish days difficult trails coming up through El Paso connected New Mexican colonials tenuously with their parent civilization far to the south, and names like Jornada del Muerto, “dead man’s march,” testify to the perils that were found there. Nor is there any real sportfishing where the Rio Grande becomes a real river again down in the Big Bend, though I remember we took much tackle with us on that cheerfully ignorant expedition to the Conchos one spring nearly two decades ago.

If I wanted to be contrary in a picayune sort of way, I might argue that we actually made that trip on the Rio Grande itself, for a number of respectable authorities—among them intrepid, wooden-boat-encumbered, canyon-surveying, desert-hating Robert T. Hill—have maintained that the Conchos is the mother stem of the Rio Grande system because of the immensely greater volume of water it brings to the confluence at Ojinaga-Presidio, the place early Spaniards had named Junta de los Ríos.

We made an effort to learn what we could about the Conchos beforehand, but that turned out to be very little. All we were able to glean came from a couple of sketchy maps, and in gladsome consequence, whether or not we were the first to paddle all the way down the last 130 miles of the Conchos (or whatever it was; I’ve still never seen a decent map on which close measurements could be made), we were at least able to believe that we were first—latter-day incarnations of Meriwether Lewis and John Wesley Powell, with maybe a touch of French-Canadian coureurs de bois and for that matter Robert T. Hill. This was, I admit, maybe a rather boyish feeling for six grown men in three aluminum canoes to have, but it was a fine one nonetheless and was enhanced rather than dashed by vague, rather gleeful accounts from Mexican customs officials of an enormous deadly waterfall—or was it several?—somewhere in the depths of the Conchos canyons.

In any event, we found enough river adventure to keep that feeling alive, along with some awesome and spectacular places in whose like I had not been before. Places that were twilit in midafternoon, the sky a thin bright slit hundreds or sometimes thousands of feet overhead, with perhaps a golden eagle or falcon momentarily silhouetted against it, and the only sounds, down where we were, a faint murmur of potent water against carved canyon walls and nearly always the muted hollow twitter of cliff swallows whose mud nests adorned those walls, with now and then the distant down-laughing note of a canyon wren, a raven’s croak, the rap of someone’s paddle against a gunwale. We had upsets in rapids here and there, a few portages where nerve failed us or good sense didn’t, and always the pit-of-the-stomach wonder about that big waterfall. Villagers we met along the way made it sound like a huge bathtub drain down which canoes would be inexorably sucked.

These people on the whole turned out to be among the most receptive and likable I’ve ever found on trips to Mexico, curious but not nosy about what we were doing and wanting to help to the extent that the intensely parochial tenor of their lives and their ken permitted. Their presence made the trip much different from the wilderness jaunt we’d envisioned, but it was still wilderness in a way because they were there so organically, a part of the river’s fauna.

Even back in the wilds of the canyons and the rough hilly desert, where there would be coyote and javelina and mountain lion tracks in sand by the water in the mornings, we found a few human beings, most of them outlaws of a hardworking amiable sort. These were sturdy souls engaged in harvesting candelilla, a low, many-fingered spurge plant of the region, and rendering out its industrially useful wax by boiling the stuff in iron vats set up in secret places along the river. They were outlaws because in a poor region of a poor country the candelilla trade was fairly profitable, and the government sought to restrict its harvest to favored licensees. They had the dash and certitude and color that being outside the law can give, together with the courtesy and aplomb that being country Mexican practically always does, and also more knowledge of the region than their kinsmen in the pueblos.

We found five raffish-looking friendly outlaws at their wax camp in a pile of boulders one morning, and they had the enlightenment we craved. Yes, said their mustachioed, bold-eyed leader, the waterfall lay only three or four kilometers downstream, and it was very frankly, my friend, an unholy son of a bitch, a place where the river ran between and beneath stones much bigger than houses and no boat could possibly pass. And so, quite exactly, it turned out to be, except that beside the falls—a huge long cascade down through a rockslide, really—we found a couple of other affable wax-camp types tending catfish lines, who for a few pesos each helped us mightily with a tough portage over boulders and chasms and reduced to two or three hours what could have been a day’s work.

I’m told there are big modern dams in the Conchos now, with good new roads running near the river and the pueblos, but they say also that despite that kind of change the candelilleros are still functioning and still being kept on the dodge, not only in their native land but in ours too, since “wax weed” abounds in Big Bend National Park, and park personnel with quite commendable ecological viewpoint try constantly to prevent its harvest. Myself, I’d hate having to persecute such noble criminals as those, but on the other hand their lives are no doubt made richer and fuller and more vibrant by that sustained matching of wits.

Few of them are simmering spurge beside the Rio Grande itself these days, however, even those who gather plants in the park. On that recent four-day raft trip through several canyons, we saw only some flood-silted remains of disused boilers and their stone fire pits in the Mexican side, which, should they endure, will in time, I guess, take on an archeological aura of the sort that attaches to the area’s old Indian caves, petroglyphs, walls of melted adobe and tumbled stone with bloody tales behind them, mine shafts, and ruined riverbank hot-spring spas where once travelers came from far and wide to achieve a cure, it is said, for gonorrhea and other rooted ills.

The problem is not so much an excess of law enforcement, it seems, as a lack of privacy, for no self-respecting outlaw would want to carry on his operations in the public gaze. And the public gaze is what the Rio Grande’s shoreline gets a great deal of these days in the Big Bend, which until the thirties and later was the river’s true wilderness section, a hostile, difficult, beautiful place where no one went from outside without compelling reason. Establishment of the national park and the building of access roads not only have changed that state of things but have just about turned it around. Now, from the point where river canyons begin, well upriver from the park’s western boundary, to far beyond its eastern one where they disappear in Lake Amistad, the Rio Grande’s course has been intricately charted, its navigational hazards analyzed and rated on an established white-water scale of one to six, its features of interest noted and described in maps and booklets available to those who want to run any or all of the canyons in canoes, rubber rafts, kayaks, or for that matter shallow-draft jet motorboats. And on days when the river is right, neither so low as to make travel hard nor so high as to make it dangerous, anywhere from scores to hundreds of healthy outdoor Americans are likely to be doing so.

A lot of river is there, of course—about 235 miles in the part most commonly used—with a good many put-in and take-out points, so that few stretches are more than occasionally what could be called crowded, unless perhaps by a Robert T. Hill or a wax-camp operator. Moreover, the people who go there to float, whether in pairs or small groups or sizeable commercial flotillas of rafts maneuvered by skillful guides, are for the most part the kind who go to see the river and the country for what they are, since fishing in the alkaline, usually turbid water is poor except for catfish caught on bait, and there are no standard American-garish attractions along the way, or even any standard American comforts beyond some showers and flush toilets at Rio Grande Village, where a good many canyon trips end. It is not, in other words, a suitable or comfortable place for large, loud, pleasure-bent groups of sightseers and revelers of the kind so often found amid the fleshpots of the Lower Valley, and there are no such around. Outside of some members of the jet-boat set, who seem always to be at the point of getting themselves banned by park authorities but never quite achieve that desirable status, most of the Big Bend’s boat folk are clearly good, quiet, interested sorts, often gifted with wilderness skills and sensitivities and knowledge and no more anxious to disrupt others’ enjoyment of the river than they are to have their own disrupted.

For the more solitary-minded among them, though, having others there at all does diminish what they came for. Treasuring wildness, they have journeyed there to be alone with it, either individually or with four or five friends at the most, because being alone with wildness is what wildness is all about. And the presence of other people, even or maybe especially other people who treasure it too, is a diminution of wildness and a diminution of the aloneness they seek. Crowds are not needed to achieve the diminution; it resides in the knowledge that on any given day you are most likely going to encounter, briefly, one or two or five or six other parties, passing them or being passed. In that mere knowledge there is a fracture of solitude, a using up of wildness.

You could see it, on that raft trip, in the quiet, almost embarrassed greetings that were given in return for ours, whenever two or three canoes passed us in a canyon of the Bend or in one of its long, winding, bird-loud desert stretches. Sometimes, more rarely, you would see it in the set jaw and averted gaze of some possessive African duck type who passed in hostile silence. I had come with a good-sized party of people on that trip and did not expect solitude, but if I had come with such expectation I think I’d have been hostile too.

There is irony. On that long-ago cheerful journey we made down the Conchos not knowing what to expect, we undoubtedly saw more human beings in an average day than you can count on seeing now along the Rio Grande, but because they so honestly and unthinkingly belonged where they were, they left the wildness intact for us and we possessed the aloneness that, without defining it, we had been looking for when we came. And in contrast, on the magnificent, admirably preserved river of the Bend, where you see only a few people who want to belong but don’t really, aloneness is hard to have.

Maybe we could all wear Mexican straw hats.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Big Bend