This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

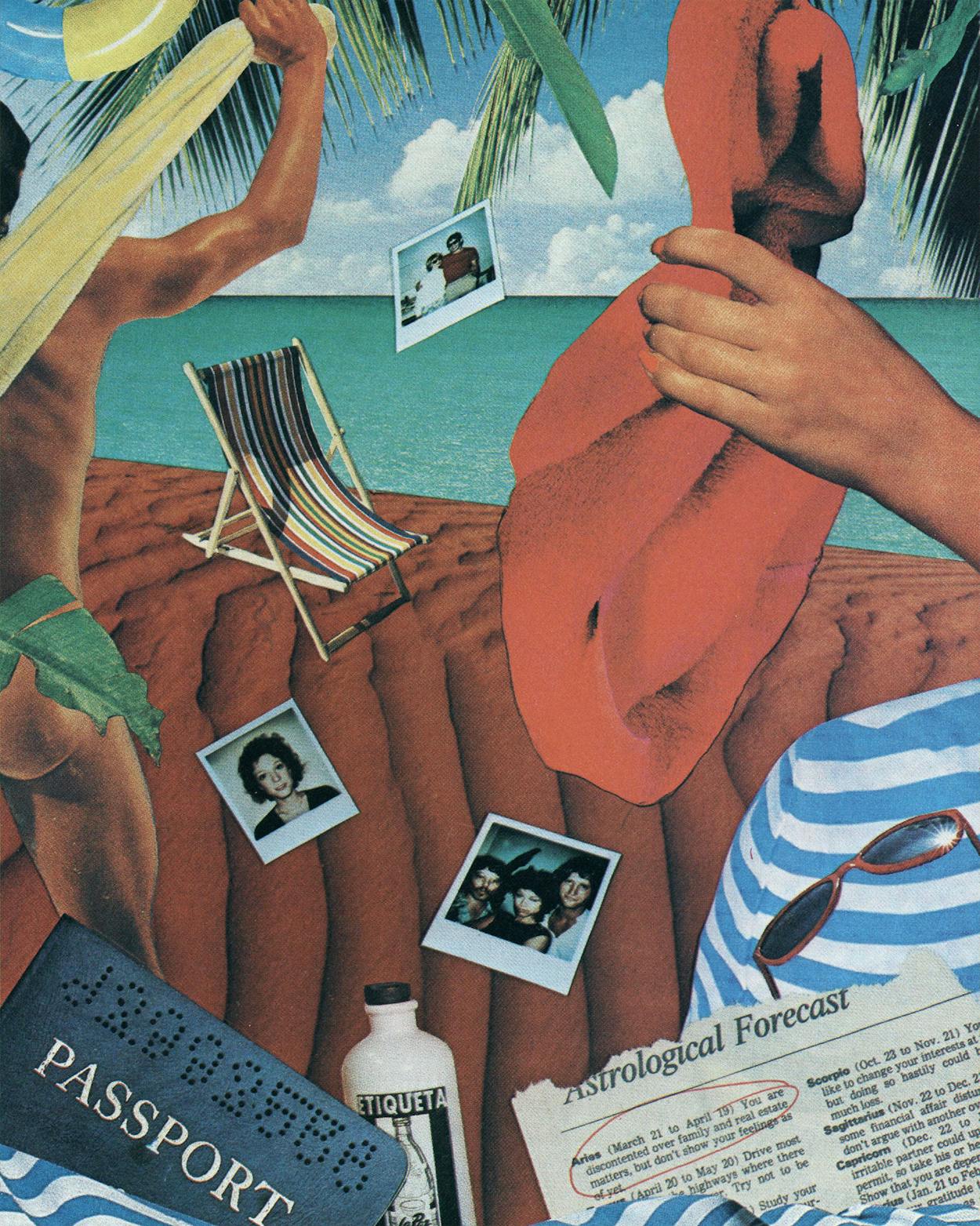

There is a beach in southern Mexico where the whiteness of the sand can blind you and at night the moon hangs like a lamp above your bed. It is on the Pacific Coast, where the horizon is blue and as limitless as eternity itself and the waves can swallow you up without missing a beat. The prehistoric hills of the state of Oaxaca begin behind the last sand dune and stretch on until they join the major range of mountains between the coast and the state capital, also named Oaxaca. The bus trip between Puerto Angel, where the beach is, and the city of Oaxaca, where most people begin their journey to the coast, can be steamy or rainy, sometimes bitter cold, sometimes get-out-and-help-the-driver-push.

Puerto Angel is a pleasant fishing village of a few thousand souls. It’s easy to imagine that the Port of the Angel got its name from a nervous priest trying to counter the bad mojo of the nearby beach. The beach was christened Zapolite by the Indians who, long before Cortez landed in the Yucatán, made human sacrifices there. The name means Playa de la Muerte, or Beach of Death. But it is the ocean, more than anything else, that gives the name “Zapolite” meaning still.

“Once,” someone may mention in casual conversation on the beach, “seven people drowned here in one week.” Who knows if the story is true? The Mexicans who live here year-round are the only people who could keep an accurate count of such things. But to them—as they sell their beer and bananas and fried fish to the young Europeans and Americans on the beach—seven drowned gringos are not a much greater tragedy than one drowned gringo. The Mexicans on the beach are a hardy and skeptical people. They go into the water only to fish, and they carry crowbars to discourage stray sharks.

The Mexicans know how deceptive the water at Zapolite can be. Just when you think you know the currents, you’ll put your feet down for a rest and realize that you’re in over your head. You’ll raise your legs and start swimming in, a little more tired than you were a minute ago, and then the first big wave will hit and send you tumbling end over end underwater. Then another wave will hit, and you’ll begin to understand why the Indians named the beach what they did.

In all truly exotic places, the one extreme, danger, is balanced by another extreme—at Zapolite, by romance. The young visitors to this alternative vacation spot know the mile-long stretch of sand by a more popular name: the Beach of Love. You need only look at the women strolling by to know why.

The beach attracts a disproportionate number of French-speaking people (Quebecois, French, and Swiss) who travel Mexico for months at a time, in vans and cars, and camp on the sand or live in thatched-roof cabanas with Mexican families. Some of the European women work for their room and board, shuttling beer from the Mexicans’ refrigerators to the men on the sand. Some of the tourists, especially the French, believing in a liberal education for their children, rear their babies alongside the Mexican babies. The French women also set fashion on the beach, dressing for the evening in wet hair, dangling earrings, and oversized men’s shirts.

There are gravel-voiced Italian girls at Zapolite who know how to blow cigarette smoke straight up, away from the eyes of the men they talk to so intently. There are sleek American girls, tall and tan and glittering with bracelets, who look like models: hip, tough (an air that Europeans cannot achieve), looking for something, anything, excitement. They will never be this young and beautiful again, and they know it.

Some of the American women are products of the Eastern Establishment, Smith College graduates who chopped sugarcane in Castro’s Cuba, women whose every liberal bone trembles at the thought of being made love to by a South American or a Mexican. Granola Girls from Colorado and Central Texas, preoccupied with whole foods and the occult, come to Zapolite to consult the stars. In groups these women walk down the beach, moving like troupes of performers. They are all casually athletic and hard-hearted—a little cynical, as all beautiful, willful women are—and after two weeks in the sun at Zapolite their breasts resemble scoops of chocolate ice cream.

The opportunities for love at Zapolite are first-rate, especially for women, because the Latin men on the beach—Mexicans, Italians, South Americans—are much more prepared to pamper women and to be pampered by them than the average Western male is. The Latins believe that women want first, foremost, and above all to be made love to. And in such a setting!

When the sun rises, it is as if God has chosen you personally to view the best of His creation. If you get up early—most people find it impossible to sleep through the red sunrise—the sea looks like molten silver, and there may be wild horses playing on the sand or porpoises playing out near Pelican Rock or, farther out still, whales jumping, while thirty pelicans line up wingtip to wingtip to form an eerie V and silently glide southward along the shoreline to the next bay, where they meet the fishing fleet as it comes in with its morning catch.

At the end of the beach, below Casa de Gloria, the hotel that sits on top of the cliffs, there are shallows in the surf where lovers can lie on the sand and be washed by the tide, where a man and a woman can spread out in the water face to face, like a four-pointed human star, whispering and kissing.

But looking out over the water and commenting on the allure of this place, Alejandro of Mexico City (there are no last names at Zapolite), who has come all the way from school in France just to chase girls over the New Year’s holiday, put into words the fear that is in the back of every visitor’s mind. “Very beautiful,” he said, gesturing at Zapolite’s charms, “but you pay for what you get.”

Casa de Gloria is not a traditional hotel. There are no rooms, just cabanas with dirt floors. When Gloria has many guests, as is the case during “high season,” roughly from December to April, she may lead you to a palm-leaf lean-to, where you can sling a hammock and sleep in between trips to the beach. There is no running water at Gloria’s, and there are outdoor toilets only.

Gloria is a mystery, a woman of unrevealed origins, and she likes it that way. After eight years in the Oaxaca sun, Gloria is so dark that she could pass for a Mexican if she weren’t so robust, so clearly the product of Anglo civilization and culture. She is American, from California or the deep Southwest—that much is certain. But whatever else there is to learn about Gloria comes in bits and pieces, colored by the karma of the beach. For a radius of fifty miles, Gloria is the most gossiped-about person, especially among the Mexicans, some of whom are convinced that she is a witch.

She runs Casa de Gloria the way Humphrey Bogart ran Rick’s American Cafe in Casablanca. You might overhear her confide to someone at the counter in her restaurant, as she did recently, “I used to own a zodiac shop in L.A.” You might hear her talk about having been married at age fifteen. Or if she’s being especially sharing, she may tell you the story of the small altar in front of her restaurant. It’s an altar like those found everywhere in Mexico, with a place for a candle below a picture, except that the picture is not of Christ or the Virgin but of what appears to be a California sun-child—Gloria’s daughter, who died of malaria at Zapolite a few years ago. After her daughter’s death, Gloria closed down the hotel and returned to the States for a while. But she gives the impression that she could never leave for more than a few months, that she too will die here one day.

The beach directly below Casa de Gloria has been set aside by custom as a nude-bathing area. The Mexican matrons who control the rest of Playa de la Muerta view nude bathers with the grim disapproval of Grand Inquisitors. Gloria herself is no libertine. At her hotel, clothes must be worn, and sometimes, when she has just warned someone wandering up from the beach to put his clothes back on, Gloria gives another impression—that no matter what she may have believed more than a decade ago, when she first drifted to Mexico burned out from the sixties, she no longer advocates free love. “You wouldn’t believe the things I’ve seen,” she says with some horror. “a couple comes here, and in a few days he’s sleeping with somebody else. Then she’s sleeping with somebody else. Then she splits for the Yucatán with somebody completely new and leaves the kids here.”

Everybody stays at Gloria’s: postcommune, precomputer travelers who roam the Western Hemisphere like gypsies, bringing along children and a car, looking for positive vibrations and natural surroundings; oil heiresses and French grandmothers who arrive in taxis from Acapulco or Puerto Escondido, 35 miles up the coast, and walk the beach at Zapolite just as naked as the day they were born; people who for one reason or another are on the run from their old lives. The thing that most of these people have in common, and the thing that is mildly unnerving to the unbeliever, is that they came to Oaxaca because their astrological charts told them to. Make no mistake, though. For all of Zapolite’s spiritual attractions, the highest priority of the tourists here is to get a good tan.

One February, on this strange beach with its strange aura and alternative values, a minor morality tale was played out. The afternoon the trouble began, Gloria sat in the dark in her house, talking to her adopted son, Juan. She was trying to explain to Juan why his fiancée had just run off to the mountains. Nineteen-year-old Juan was to have married fifteen-year-old Lucy, a waitress in Gloria’s restaurant. Things had begun innocently enough that morning when Gloria took a complaint from one of the guests about Lucy’s manner. Nothing new about that—Lucy, a pretty, jaded girl, worked ten-hour days in a hot kitchen and didn’t think much of the frivolous foreigners she served. Gloria passed the complaint on to Lucy’s mother, Josepha, who also managed the restaurant, and that’s where the argument started. Gloria told Josepha, “This isn’t the first time I’ve heard that about your daughter.” “Your daughter”—Gloria used the phrase over and over again, talking to Josepha. Maybe it was the heat, maybe it was the yellow moon that had looked like Satan’s eye a few days before, maybe it was just tension related to the impending union of these two families, but whatever the reason, Josepha flew off the handle and started throwing dishes. By the time the crockery was swept away, Josepha had departed for her village in the mountains, taking Lucy with her and vowing never to return.

Gloria explained to Juan what had happened, without ever really apologizing, not even for her poor choice of words with Josepha. Standing there in Gloria’s house at dusk, the wind off the Pacific blowing through the windows at his back and causing all manner of chimes and amulets hanging from the walls and furniture to jangle softly, Juan listened attentively, ignoring Gloria’s husband, Carlos, who was moving restlessly around the room.

Finally, as Juan stepped outside into the night and started down the trail to the hotel, Gloria called him back. “Forget everything here,” Gloria counseled him in Spanish. “Forget me and Josepha. If you love Lucy, go after her and find her and don’t look back.” Juan stared at Gloria for a long second. Without saying anything, he disappeared down the trail.

The next morning, just after sunrise, Gloria’s guests were awakened by a bloodcurdling scream, followed by the sound of crashing dishes. The guests who were already up and ordering coffee in the restaurant said the scene resembled an act from some steamy play, with fiery Carlos, who is 26, telling Gloria, who is 38, “You took the best years of my life!”

The argument had heated up, and Gloria had screamed as if she had been stabbed through the heart. Then Carlos started throwing dishes. He and Gloria had just celebrated their first wedding anniversary (Carlos is Gloria’s third husband), and they were supposed to go away to Oaxaca for a few days’ celebration. But when Carlos left that morning, he left alone, stomping down the beach. Within hours Gloria had packed a bag and gone after him, leaving one of the restaurant employees, Starlight—a delicate Belgian woman and a veteran of every quiche joint and Perrier palace on the Granola Trail between Colorado and California—in charge.

Suddenly almost the entire staff of the hotel was gone, yet 25 guests remained. Drastic measures were called for if Casa de Gloria was not to fall into the sea. In Gloria’s absence, therefore, Casa de Gloria came to be ruled by a Council of Five, headed by Starlight and including four guests, none of whom had even been in Mexico three months earlier. The council took control of everything from the hotel’s purse strings to its menu.

The four governing guests were Barbara, an advocate of every liberal American cause since Selma and a particularly close friend of Gloria’s (they both had lovers younger than themselves); Peter, from rural Sweden, a real gentle man, who had met Barbara on a commune in the Midwest; Wolfgang, from Stuttgart, a young man with an earthy sense of humor (it was he who first suggested that the International Diarrhea Championship be held at Zapolite); and Wolfgang’s beautiful girlfriend, Diana, an artist.

Gloria’s instructions were that the hotel was to be run the way it had always been run—on instinct, making enough money to meet expenses and a little more. She had made it clear that she would be happy if the hotel was still standing when she returned. So, in the absence of the demands of grinding capitalism, the hotel managers, that is, the Council of Five, chose an alternative business goal: maximizing time on the beach. Gloria had kept the restaurant open from eight in the morning until ten at night, but the Council of Five changed the closing time to nine and added a siesta from two till four in the afternoon.

The issue debated the most, however, was who would sleep in Gloria’s house. No one wanted to, although everyone was embarrassed to say why. They all thought the place was spooky. Gloria’s house had been built by a Texan named Robert, a genius, apparently—it was said that he had spent only $800 to create one of the most beautiful seaside homes in the world. The house was eight-sided, made of thick bamboo, with rough tile floors, and it sat on a cliff a few hundred feet above the Pacific. Surrounding the house was a corral, where Carlos kept a horse, and a sign above the corral—a sign like those you see over ranch gates in Texas—read “NIRVANA” in block letters. Inside the house, among other furnishings, was a chair made entirely of whalebone. What revealed the most about Gloria’s character and interests was the rows of books in her bookcases. A quick look at those books made it easy to see why the local campesinos thought Gloria had gone beyond the bounds of standard Judeo-Christian morality: Bhagavad Gita, The Tahitian Book of the Dead, Jesus the Son of Man, by Kahlil Gibran, A Separate Reality: Further Conversations with Don Juan, and No One Here Gets Out Alive, the biography of the late Jim Morrison.

The last thing Gloria said before leaving was that George—a handyman and, as he frequently boasted, a native Texan—had no authority in the kitchen. George fancied himself the best cook at Casa de Gloria (there was some evidence to back him up), and he ignored Gloria’s instructions. In the days that followed, Starlight, more an ethereal than a real being, found herself intimidated by George’s tough talk.

George was from East Texas, somewhere. He was vague about how he first arrived in Oaxaca (and it didn’t seem tactful to ask), but he did say that he had been at Gloria’s “a year, this time.” He was apparently either on the cure or waiting out some storm in Texas.

George was definitely preparing to sit out World War III, which he believed imminent. Every night before dozing off, he listened to Voice of America on the shortwave, and in his semiconscious state he heard the political commentator talking about Soviet intransigence and Cuban adventurism (half of the broadcasts were devoted to attacks on communism). With the Voice of America and old copies of Newsweek as his only sources of information, George thought that Armageddon was just around the corner. No one had the heart to tell him that the wind could carry the radiation as far as Oaxaca, easy, and that if he really wanted to escape the bomb, he needed to keep going south another few thousand miles or so.

George considered certain social graces mere frills to the business of LIFE. More than once he walked into the kitchen when Starlight or someone else was slaving over a big pot of vegetarian chili, took a taste, and pronounced, “This is slop! Who do you think’s gonna eat this?” Not all the guests spoke English, but there was no missing George’s meaning on such occasions. His comments, and sometimes the food itself, had an adverse effect on the restaurant’s trade. A few guests deserted Gloria’s restaurant to eat at the casas on the beach. And sometimes Starlight retreated from the kitchen entirely, leaving everything in George’s hands.

Still, the hotel was surprisingly well run. Sure, there were minor problems—guests came, guests went, as at any other inn—but only once did any guests leave because they did not like the accommodations. They were three older American women who arrived out of the blue one day; they must have taken a wrong turn leaving Acapulco, and they looked as if they belonged to a tour group from Fort Worth. They were genuinely shocked by what they ate and what they saw at Zapolite.

What they saw was the beginnings of the decline of Western civilization—decadence, marijuana, Oaxaca gold going for $20 a half pound, people who had lost their dreams because every night they went to bed stoned. But as the American ladies might have learned, had they stayed, being unable to dream at Zapolite is really for the best. There is so much unreality at the beach that nobody ever misses his dreams.

Zapolite is patrolled by Mexican marines from the naval base in Puerto Angel. The marines do double duty as the local police, and when they patrol the beach (usually once every other day), they look for marijuana smokers and nude bathers. Hiding behind rocks, carrying rifles bigger than themselves, the marines will watch for a while—if the bathers are women—before telling them to put their clothes back on. It is a tribute to Gloria’s influence on local politics that the marines are forbidden to set foot on her property, although they can search the Mexican-owned casas on the beach at will.

The day after Gloria and Carlos departed, however, the marines came to the beach three times, and they returned every day, repeatedly and without warning. The stepped-up visits created a paranoia at Casa de Gloria, and it only worsened with reports (which turned out to be true) that the army had begun conducting surprise searches at the crossroads outside Puerto Angel. All of this official activity led the members of the Council of Five to believe that the hotel was due for a raid or trouble of some sort from the authorities. They began to think that without Gloria or Carlos on the premises, the hotel was vulnerable. Starlight didn’t speak Spanish, and none of the five had working papers. They knew that if the authorities ever came to the hotel, they would probably shut it down. After all, for those few days Casa de Gloria was the weirdest social phenomenon in the state of Oaxaca, in a country where such things are noticed.

To her credit, Gloria doesn’t allow liquor or drugs on her property. But while she was gone, the rules were bent. There were times late at night when, had the marines ventured up from the beach, they would have found almost everyone stoned or in the restaurant pigging out.

But on the tenth day after Gloria’s departure the spell was broken. Peter went into Puerto Angel to shop for the restaurant, and a taxi driver told him that the military checks and patrols were part of the search for a dozen guerrillas who had escaped from the state police up the road in Pochutla. Peter didn’t know Oaxaca even had guerrillas, but it was good news nonetheless.

That afternoon, as Peter emerged from the market, he heard something even better. He ran into an American woman, an artist living in Puerto Angel, and as they exchanged pleasantries, she said, “You mean Gloria’s not back?”

“What?” Peter said.

“I had an opening for my work in Oaxaca two days ago,” she said, “and I ran into Gloria and Carlos. They were back together. Juan and Lucy were with them too, and Juan said that he’d found a ring. They said they were going to Mexico City for a day to visit Carlos’ family, but they were supposed to be back yesterday.” The wedding ceremony, she added, would be held on the beach below Casa de Gloria, followed by a celebration that would wake the dead.

Within hours of receiving the news, the Council of Five began to disband. Since Gloria was returning, everyone went on with the plans that had been postponed by her departure.

Amid tears of farewell Barbara and Peter left for the Yucatán, a first step on their way to West Virginia, where they would build a house and start their married life. Wolfgang and Diana left for Nuevo Laredo, to go from there to visit a friend in Austin before flying home to Germany. And Starlight, leaving a new crew in the kitchen—all of them guests of the hotel—was headed for Guatemala as soon as Gloria arrived.

In many ways Barbara was the most perceptive member of the Council of Five, and the night before she and Peter departed, she commented that Casa de Gloria seemed to have a life of its own. She suggested that maybe it wasn’t the first time that Gloria had taken off and left her hotel in the hands of the guests. Seventy cents a day plus meals is too low a price to pay for paradise, Barbara said. Guests who spend a long time at Casa de Gloria end up making another contribution to the upkeep of the hotel. And because they do, Barbara said, they will remember their vacation at Puerto Angel for the rest of their lives. If Gloria is a witch, that is her magic.

Lucius Lomax is a freelance writer.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Mexico

- Longreads