About halfway between Fort Stockton and Van Horn, in West Texas, dip down off Interstate 10 to a tract of the Trans-Pecos where desert meets mountain in spare and spectacular fashion. Sparsely populated, this remote and rugged country is nevertheless home to a quintessential Western town, a historic military installation, a desert research institute, and a world-class astronomical observatory. It’s an almost perfect locus from which to immerse oneself in the mysteries of the cosmos, the lore of the Old West, and the lavalike layers of geological history. And at its sunbaked heart lie destinations that for many are the main attraction: Davis Mountains State Park and its beloved Indian Lodge, a rustic inn whose pueblo-style architecture and canyon setting have made it an oasis for traveling Texans for 86 years.

At 2,709 acres, the park captures a swath of the rolling grasslands, scrubby hills, and forested “sky island” pinnacles that distinguish the Davis Mountains, the largest and highest range located entirely in the state of Texas. The isolated peaks were once called the Limpia Mountains, for the creek (limpia means “clean” or “pure” in Spanish) that U.S. Army engineers happily stumbled upon while scouting this harsh country for westward wagon routes, in 1849. And some would like to see that name restored: the range was rechristened not long after the 1854 establishment of Fort Davis, itself named for then–secretary of war Jefferson Davis, who would later become president of the Confederacy. Now the orderly garrison, set in a box canyon just east of the mountain range (and a 1.4-mile hike from the park’s eastern boundary), is a national historic site, where visitors enjoy reenactments of life on the frontier and learn about the fort’s original raison d’être: to protect wagon trains carrying freight, mail, migrants, and fortune seekers from so-called outlaws, whose number included Native Americans rightfully none too pleased about centuries of foreign incursions.

The longing for safe passage feels familiar in this pandemic era, even if the journeys we dare to take are a little less dramatic. But the ease with which visitors arrive at a sense of refuge in a landscape defined by endless sky, wind-carved rock, menacing vegetation, and formidable critters is still surprising. A desert, wrote Edward Abbey, “can hardly be called a humane environment; what little human life there is will be clustered about the oases, natural or man-made. The desert waits outside, desolate and still and strange, unfamiliar and often grotesque in its forms and colors, inhabited by rare, furtive creatures of incredible hardiness. . . .” And yet this far-flung spot has long been a way station, a respite of inhospitable beauty for those on their way to somewhere else. Nowadays, those travelers are more likely to be migrating monarch butterflies and visiting astronomers, resting summer tanagers and RV-driving wanderers, and seekers of peace and other intangible treasures.

Rare and furtive were the critters when my park pal and I left our rooms at Indian Lodge and joined a puffy-jacketed brigade of birdwatchers for a morning walk along the Seep Trail Loop, which, at little more than a mile, crisscrosses the mostly dry bed of Limpia Creek. These were the halcyon days of February 2020, when the park still hosted events such as “Mindfulness Walk in Limpia Canyon” and “Hike With a Homeless Dog.” Nowhere in sight were the supposed denizens of the Chihuahuan Desert, which include horny toads (hibernating), pocket gophers (underground), mountain lions (secretive), and aoudads (camouflaged). Black bears are allegedly making a comeback in the park, but (fortunately?) we didn’t see any of those. Nor did we see the javelinas who’d provided so much entertainment on previous trips out here, including the one we’d observed trying its damnedest to compromise a camper’s cooler. Our outing was rather short on bird sightings as well (a cardinal here, a mockingbird there).

But the dearth of exciting fauna just allowed for closer inspection of the indomitable, slightly terrifying flora that make this land so interesting, such as the yellow-tipped cane cholla, a favorite of cactus wrens, who nestle their eggs within its thorny, protective confines. We also admired hackberry trees, which are popular with the gray fox, who leaves in its wake bright red evidence of a satisfying meal, and parasitic mistletoe, whose berries are prized by the perky (and fun-to-say) phainopepla bird.

A Place for Us

Outside of the park, most of the land in the Davis Mountains is privately owned. Fortunately, one of those landowners is the Nature Conservancy, which opens parts of its 33,075-acre Davis Mountains Preserve to the public on specified weekends during a normal year.

Birdwatching, hiking, and camping are pretty much all there is to do inside the park, but more than fifteen miles of trails will keep you plenty occupied. We had tackled many of them over the years: The Skyline Drive Trail rewards trekkers with views of Keesey Canyon and the opportunity to study some of the park’s original stone structures, built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the thirties, including a lookout shelter and the remains of a “comfort station.” The Indian Lodge Trail is a short but challenging climb that provides spectacular vistas. For us, it also dealt broken shoes and busted butts, thanks to a painstaking descent that need not have been so precarious; we realized once we got to the end and saw the “Not a Trail” signpost that we had followed a game trail back down the mountain.

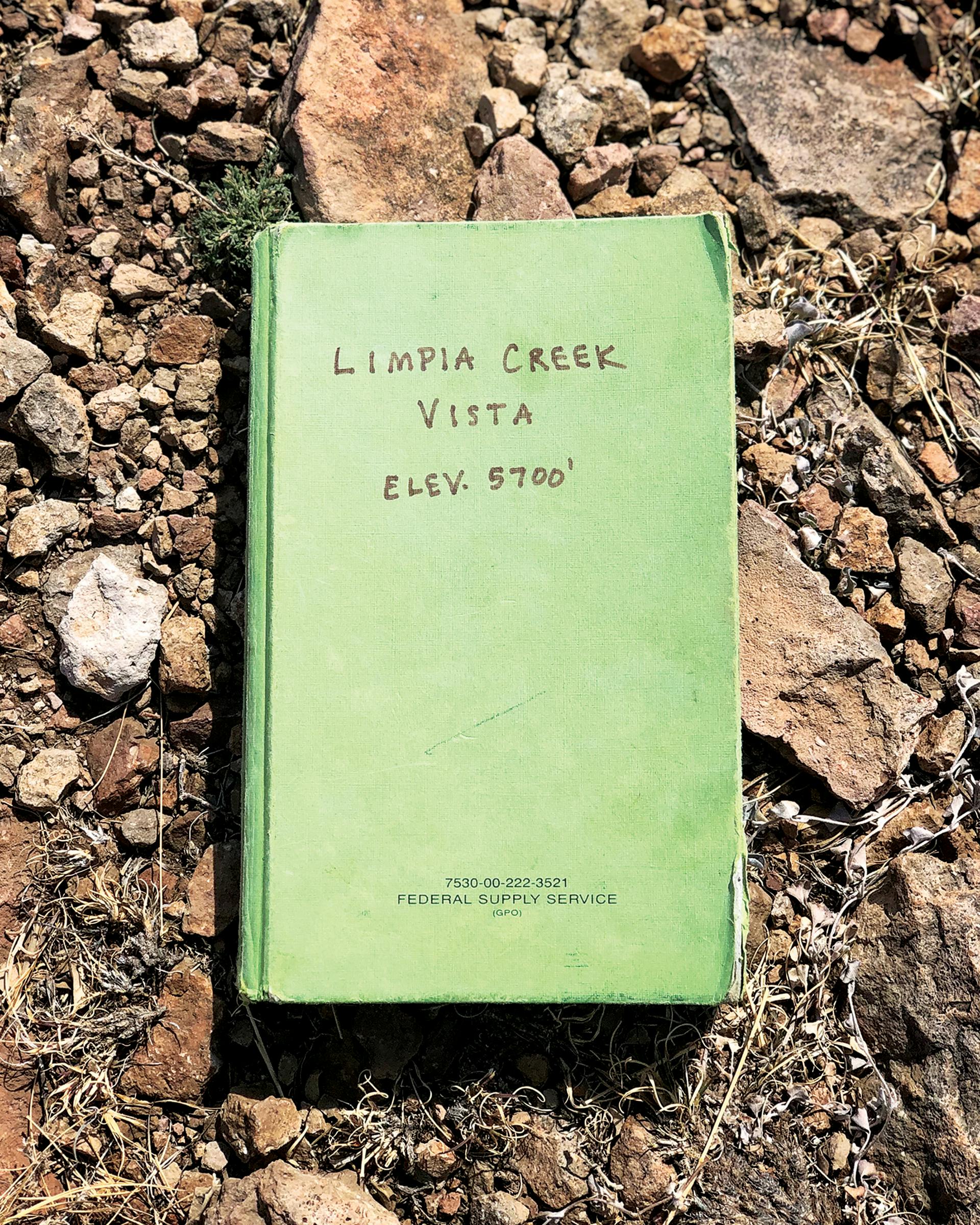

In addition to the Seep Trail Loop, we also tackled the Limpia Creek Trail, a 2.5-mile, 700-foot ascent that culminates at Limpia Creek Vista, the highest point in the park, at 5,700 feet. On a rocky path we made our way among Spanish dagger and sotol and blue-green century plants, past squat cacti with claret-hued paddles and tubular specimens sporting red and white stripes like diabolical candy canes. Up we went through taupe-colored hills speckled with oaks and rose-fruited juniper until we plateaued amid spiky, honey-colored grass, lichen-clad boulders, and craggy, rusty-red rocks, some with fractures that revealed sparkly nubbins the color of a storm cloud.

Sitting on a simple plywood bench at the top, looking out over the tiny ribbon of a highway below and the snow-white Indian Lodge shining like a beacon from afar, we opened a metal lockbox, pulled out a worn green notebook, and read the messages left by hikers who had come and gone before us. “Praise God for His creation!!” proclaimed an enthusiastic couple from Ransom Canyon. “Y’all have nice lookin’ country,” wrote a visitor from Sligo, Ireland; “Big spiders and good view” was his laconic companion’s takeaway. “Mountains have a way with dealing with overconfidence,” said one anonymous person (yep: see Indian Lodge Trail, above). A disappointed summiteer scrawled, “Where’s all the quail yo?,” no doubt hoping to see the elusive, comical-looking, dust bath–loving Montezuma. Someone named David left a cryptic bit of poetry: “The air be crisp, the morning beams. / I think I’m coming apart from the seams.”

Feeling a little worse for wear ourselves, we made it back to Indian Lodge as the sun was making an unusually grand exit, the sky a layer of creamy blue topped with a swath of fluffy pink, all of it capped with a giant dollop of tangerine moon. Turns out it was not only a Snow Moon (the name for February’s full moon) but also a supermoon, i.e., the point when the moon is at perigee, as close to Earth as it gets in its orbit.

We couldn’t have picked a better spot to bask in lunar luminosity than Indian Lodge. The inn is technically its own state park, but its picturesque location, on the north slope of Keesey Canyon, is entirely within the borders of Davis Mountains State Park. Also built by the CCC, the sixteen-room lodge was completed in 1935 to serve the newly liberated “motor tourist,” who delighted in its thick adobe walls, hand-hewn furniture, river-cane latilla ceilings, and fountain-bedecked courtyard; more rooms and an enticing turquoise pool were added in the mid-sixties. In 2006, a face-lift restored the lodge to its original handcrafted glory, and a 2017 upgrade took care of needed repairs.

Its lobby is a repository of area history, with drawers of photographs, maps, architectural plans, old brochures, and ephemera such as an original adobe brick and a CCC hatchet and pocketknife. Alas, it is closed for now, along with the pool, because of the pandemic (the inn itself is open only on weekends at this time, and reservations are required). I hope the lobby can reopen soon: it is one of my favorite places in the state, particularly in the winter, when the creaky pine floors and leather sofas are bathed in the glow of a crackling fire tended by guests who take turns feeding it logs from the stack on the porch outside. Coffee and hot chocolate are available in the office, around the corner, and volumes of Reader’s Digest Condensed Books are lined up behind a big round table invariably occupied by players of cards or dominoes.

We were lucky enough to walk into the lobby just in time for open-mic night, when participants are encouraged (in less contagious times) to bring “a story, a song, or a good clean joke.” Over the course of one evening we were treated to a body percussion dance, a poetry recitation, and a few peace-love-and-understanding ditties from a woman cruising the country in an RV with just her dog and her guitar. Outside, pressing against the casement windows, were the infinite depths of black desert night, lurking with “things that can poke, prick, bite, or sting you” (thank you, Texas State Parks Interpretive Guide). Twelve miles to the northwest, in an astronomical observatory endowed by a Paris (Texas) banker, massive, impossibly complex machinery was busy making a three-dimensional map of 2.5 million galaxies. Meanwhile, huddled in front of the lobby fire, we laughed and swapped tales with fellow travelers whom we’d most certainly never see again, having briefly passed into one another’s orbits before heading out again into the dark.

This article originally appeared in the March 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “An Unlikely Oasis.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Parks & Recs

- Fort Davis