Some 4,500 to 8,500 years ago, an unknown artist etched swirling symbols onto a shapely boulder in what is now Big Bend National Park.

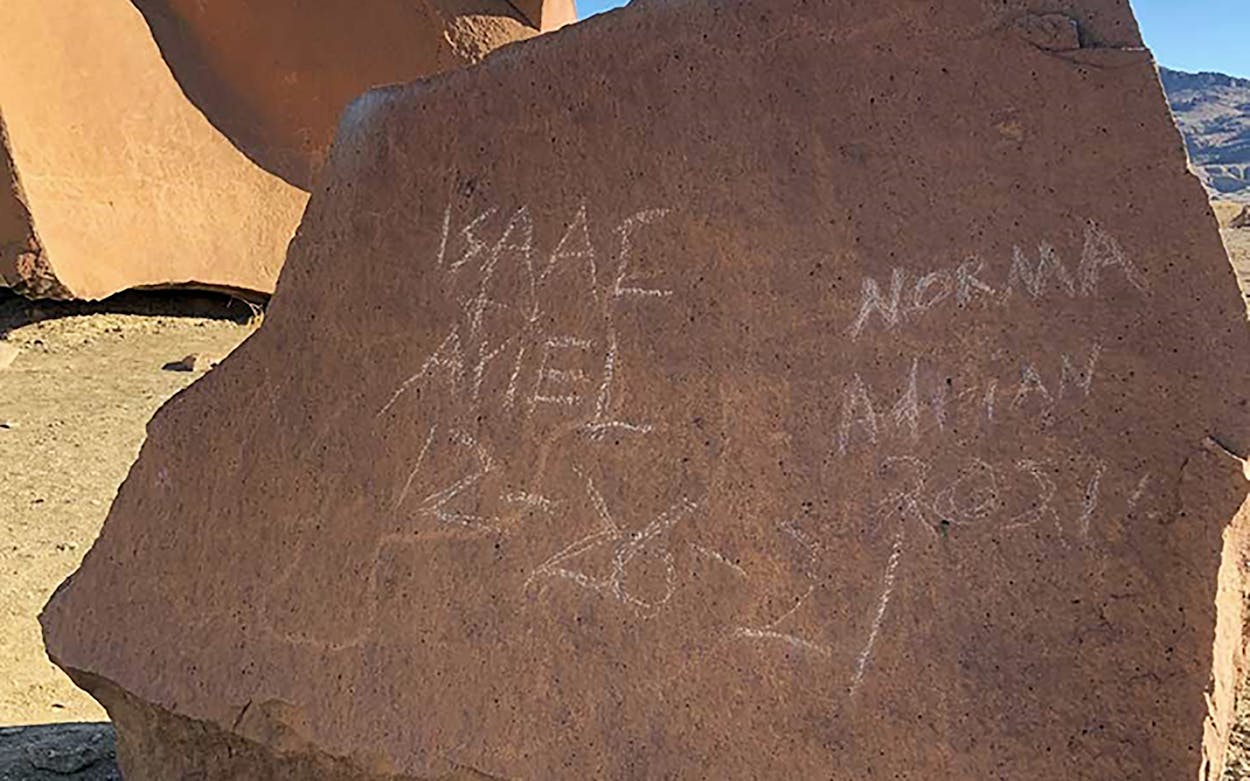

Several millennia later, on December 26, 2021, unknown visitors added a new feature to the rock art: they carved their names and the date of their crime on top of the petroglyph. Adrian, Ariel, Isaac, and Norma—or whatever your names are—if you’re reading this, a lot of folks have a question for you: What the hell?

Vandalism and looting in the beloved West Texas desert park aren’t new, but in recent years the problem has gotten worse. Since 2015, there have been fifty cases of vandalism in Big Bend National Park. The December marring was a particularly egregious case, said Tom VandenBerg, the park’s chief of interpretation and visitor services.

“Part of what we do here is take care of part of our nation’s heritage, our history, and rock art is an irreplaceable part of that history,” he says. “We love to have people discover these things, but just appreciate them and respect them as well.” Of the recent vandalism, he adds, “It’s kind of a gut punch to all of us who work here and dedicate our careers to protecting these places.”

Frustrated officials are trying a new tack: instead of dealing with the problem internally, they’re asking the public for help. This week, the park blasted out a photo of the desecrated petroglyph, saying the panel of complex abstract geometric images had been “irreparably damaged” and calling on anyone with information to get in touch. The alleged perpetrators could face criminal penalties under federal law.

The publicity prompted a torrent of outrage online. (One of my favorite comments on Instagram: “In 10,000 years or so some archeologist is going to be really confused.”) More important, it seems to have led to what VandenBerg calls “pretty strong potential leads.” VandenBerg wouldn’t share more information, but in at least one recent incident, vandals who defaced rock art at Hueco Tanks State Park were caught because they left behind important clues on the rock: their names.

Park officials are cagey about disclosing the location of the boulder—the press release refers to the “Indian Head area” in the western part of the park—but it’s not hard to find if you’re even half adept at Google. “The best way we can protect [rock art sites] is to not really provide maps or guidance to the specific locations where they are,” VandenBerg says.

The site is one of the archeologically richest in the 800,000-acre park. Situated near two springs, the area is host to a variety of petroglyphs, pictographs, metates (rock slabs once used for grinding seeds or plants), and hearths—the art-strewn living and cooking spaces of a long-ago people whose only messages from the past are communicated by what they left behind. Visitors can ponder the meaning of cryptic human forms and entoptics—the light patterns you see when you close your eyes—such as zigzagging lines and spirals.

Not so long ago, the Indian Head site was relatively unknown, visited primarily by adventurous park regulars who went to the trouble of sleuthing out its location. No more than two thousand people stopped by the site annually, according to VandenBerg. Today, that figure is four thousand.

The increased traffic at Indian Head mirrors overall trends. The pandemic unleashed an explosion in interest in state and national parks. In 2016, Big Bend National Park saw 350,000 visitors; staff are still tallying final numbers for 2021, but they expect it’ll be more than double that, around 600,000. Many of the folks coming to Big Bend are venturing into outdoor spaces for the first time. VandenBerg says the park staff welcomes the new visitors, but is dealing with the problems that come with those who haven’t been steeped in an outdoor ethos.

“If your visitation doubles, then invariably you’re going to have more people who are unaware of what public lands are,” said VandenBerg. “We literally had people that would just show up here from, say, Houston or from Los Angeles and didn’t even know what Big Bend was. Didn’t even know what you do here. But they wanted to be here. They looked at a map and said, ‘I want to go to this place that seemingly is far away from everything as I can get.’”

Of course, the vast majority of new visitors want to enjoy the park, not destroy it. But even Good Samaritans can contribute to the ruination of rock art. In the case of the Indian Head scribblers, other tourists at the site discovered and reported the vandalism, but later some well-meaning visitors made things worse by trying to clean up the mess. They’d scrubbed the boulder with water to remove the scratching, which left behind a chalky mess that damaged the rock’s natural patina.

Cleanup is a painstaking, sometimes impossible, task best left to the professionals. Archaeological technician Lin Pruitt and retired archeologist Thomas Alex used fine brushes, distilled water, and absorbent pads to gently remove the chalk residue and the graffiti. The boulder looks much better now. Hueco Tanks State Park employs a laser to remove graffiti, some of it spray-painted right over pictographs sacred to the Tigua, Mescalero Apache, Kiowa, and other Native American groups. But the process—as impressive as it is—is expensive, time-consuming, and imperfect, says park superintendent Cassie Cox. And sometimes the damage is indelible.

I’ve visited at least a half-dozen different rock art sites throughout the Lower Pecos Canyonlands of southwest Texas, one of the richest archeological areas in North America. Sadly, it’s also one of the most threatened. Climate change, floods, animals, increased humidity from the construction of nearby Amistad Reservoir, and the elements are all conspiring to wear away at the fragile rock art scattered across this vast and inhospitable region. Scientists are in a race against time to study and document the art before it is lost forever. A century’s worth of graffiti and thoughtless looting has only added to the problem. Many of the sites are somewhat protected from vandals by their remoteness and by being located, usually, on private land. Two of the most important sites—the stunning White Shaman mural on the Pecos River just upstream from the U.S. 90 bridge, and the densely painted Panther Cave on the Rio Grande in Seminole Canyon State Park—are guarded by fences. But several sites often reachable by boat on Amistad Reservoir bear the handiwork of vandals. On my phone, I have a photo of a human figure—a red, shamanlike man with an impressive phallus—painted on the chossy limestone of a cave perched above the lake. Here he stood for several thousand years, weathering climatic changes, floods, the ravages of time, the rise and fall of empires—only to be disfigured in our modern era by crude etchings by the likes of “Wes” and “LWW” and “HAAS” and “JS” and “SP.” It’s a pitiful sight.

In recent years, archeologists have increasingly come to understand the art of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands as something far more rich than the inscrutable doodles of a primitive people. The White Shaman painting, for example, appears to be a meticulously rendered creation story. An aesthetically pleasing artistic vision, yes. But it’s also likely an instructional tool used to communicate essential cultural information to successive generations. We, too, can learn about the past by studying and enjoying this art.

The guardians of Texas’s prehistoric art want folks to appreciate the value of pictographs and petroglyphs, to see them as a living connection to the past.

“Rock art tells stories of a time that is so much different than ours, but similar as well,” said Cox. “These were people just trying to survive, to live their lives with the resources they had, working through challenges and natural disasters, loving, living, raising families, just trying to make it. The art helps create a connection with those that came before us, so that we can potentially learn from them—the way they cooked food, the way they managed their natural resources, what was important to them. It tells those stories that can be shared by everybody.”

- More About:

- Big Bend

- West Texas