Houston is hard to escape. Development sprawls in every direction—“the blob that ate East Texas” is what the Economist once called the nation’s fourth-most-populous city. The never-ending urban landscape encompassed by the Grand Parkway is larger than the state of Rhode Island. Yet there is a spot in Memorial Park, just a couple of miles west of downtown, where the city disappears.

Get out of your car at the Clay Family Eastern Glades, which opened in July 2020 after a major overhaul. This hundred-acre park-within-a-park is the first completed project in the city’s ten-year, $205 million plan for Memorial, the biggest green space in Houston, and it’s a true urban oasis.

Walk across the rain garden and head right. You’ll find a picnic pavilion on the edge of the newly constructed six-acre Hines Lake. From there, as you gaze out on the serene waters, the wetland shoreline curves and follows a boardwalk that disappears behind a grove of pine trees. The water appears to go on for miles. In reality, it ends quickly at an embankment. But that’s the magic of Memorial Park’s in-progress master plan. You really do feel like you’re in the middle of nature rather than the middle of a city. You can’t hear the roar of the nearby Loop 610 freeway or the six-lane Memorial Drive that bisects the park, unlike at the Houston Arboretum down the street. There’s no whir of Metro light rail, unlike at Hermann Park’s Japanese Garden. Instead you hear the gurgles of a man-made waterfall and the cheeps of the least grebe, a small aquatic bird rarely seen inside the city before the glades opened. Turn around to look back at your car in the crowded parking lot, and the fantasy that you’re deep in nature quickly evaporates. But for one brief moment Memorial Park embodies a truism of urban horticulture: to build a successful garden is to build an illusion.

Before Half Price Books in the Rice University village shut its doors last spring, I stocked up on a collection of decades-old gardening books to help guide my attempts at building a small vegetable plot in my backyard. I was surprised to find so many tips that focused more on aesthetics than on the practicalities of fertilizer and sunlight. How do you conceal the edges of your garden to create the appearance of natural growth? How do you create the image of an organic verdancy from something that is, in reality, meticulously planned? Even a beautiful slice of nature like the Eastern Glades is fundamentally a work of artifice.

“We invented the Eastern Glades,” Thomas Woltz, the landscape architect behind Memorial Park’s new design, told me. “It’s not like it’s a restoration of anything that was ever there.”

A good garden, along with any good green space, requires design and upkeep. That’s a lesson Memorial Park learned the hard way. The one-two punch of floods from Hurricane Ike in 2008 and the severe drought in 2011 killed or threatened at least half of the trees across Houston’s most heavily used park. The land had become overgrown and unsustainable, filled with old pines and invasive species that leached nutrients from the soil. At first, park boosters agitated to replant the trees that had died and return the park to its previous, densely forested state. But the idea of Memorial Park as a piney woods was itself an illusion.

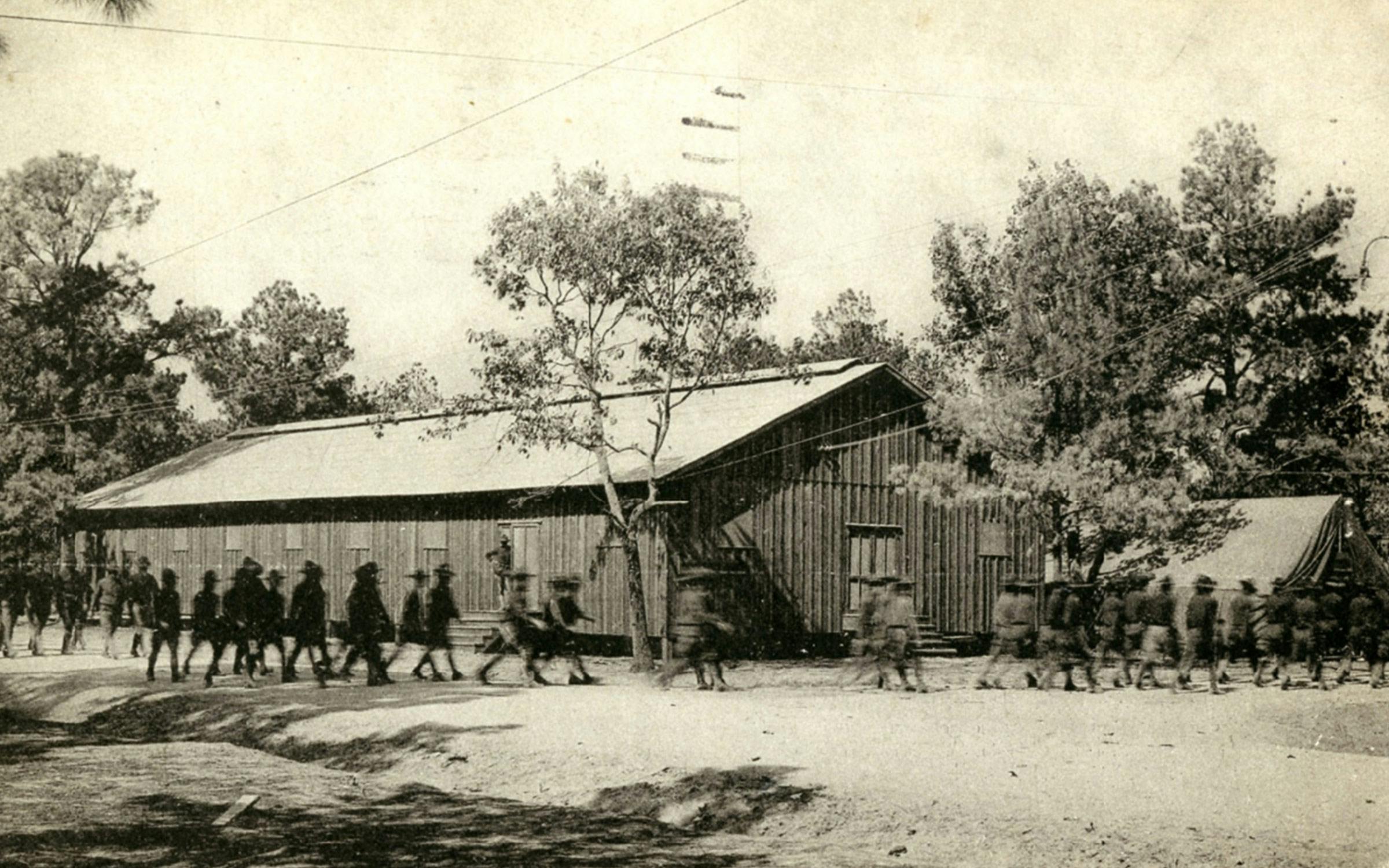

At the end of the nineteenth century, the park was the site of a brickmaking facility, orchard, and logging operation. Many of those trees had been cut down to make room for Camp Logan, a World War I training site infamous for a deadly uprising by Black soldiers who were battling racists among the local police and the community. After the end of the war, the pines refilled the campsite, burying history in a thicket of trees, all of a uniform age, all reaching a vulnerable part of their arboreal lifespan in the early twenty-first century. Peel back the layers of history, and pre-European-settler Memorial Park’s natural landscape would’ve looked like a grassy mix of wetland and coastal prairie. And even then, human intervention was likely required to maintain its verdant appearance: hidden in the soil of Memorial Park is evidence of controlled burns used by the Karankawa people to manage grasslands for hunting. Then, as now, well-maintained nature was never natural.

Out of this disaster of a dying park, the Memorial Park Conservancy decided in 2013 to rebuild the area into something more inviting. The conservancy hired Woltz, an expert in restoring damaged ecologies and owner of the Nelson Byrd Woltz landscape architecture firm. When the team first began researching how Houstonians actually used the site, they were pleasantly surprised to learn that, despite being nestled between the Galleria’s luxury boutiques and the old-money mansions of River Oaks, the park was popular with a broad spectrum of Houstonians—four million residents from 170 zip codes visited each year. Less encouraging was the fact that many of them used Memorial Park only for its jogging trails, as if this vast landscape were little more than a 1,500-acre outdoor treadmill. With much of the space occupied by dense thickets of dying trees, there wasn’t much else you could do. It was clear that the park wasn’t living up to its potential.

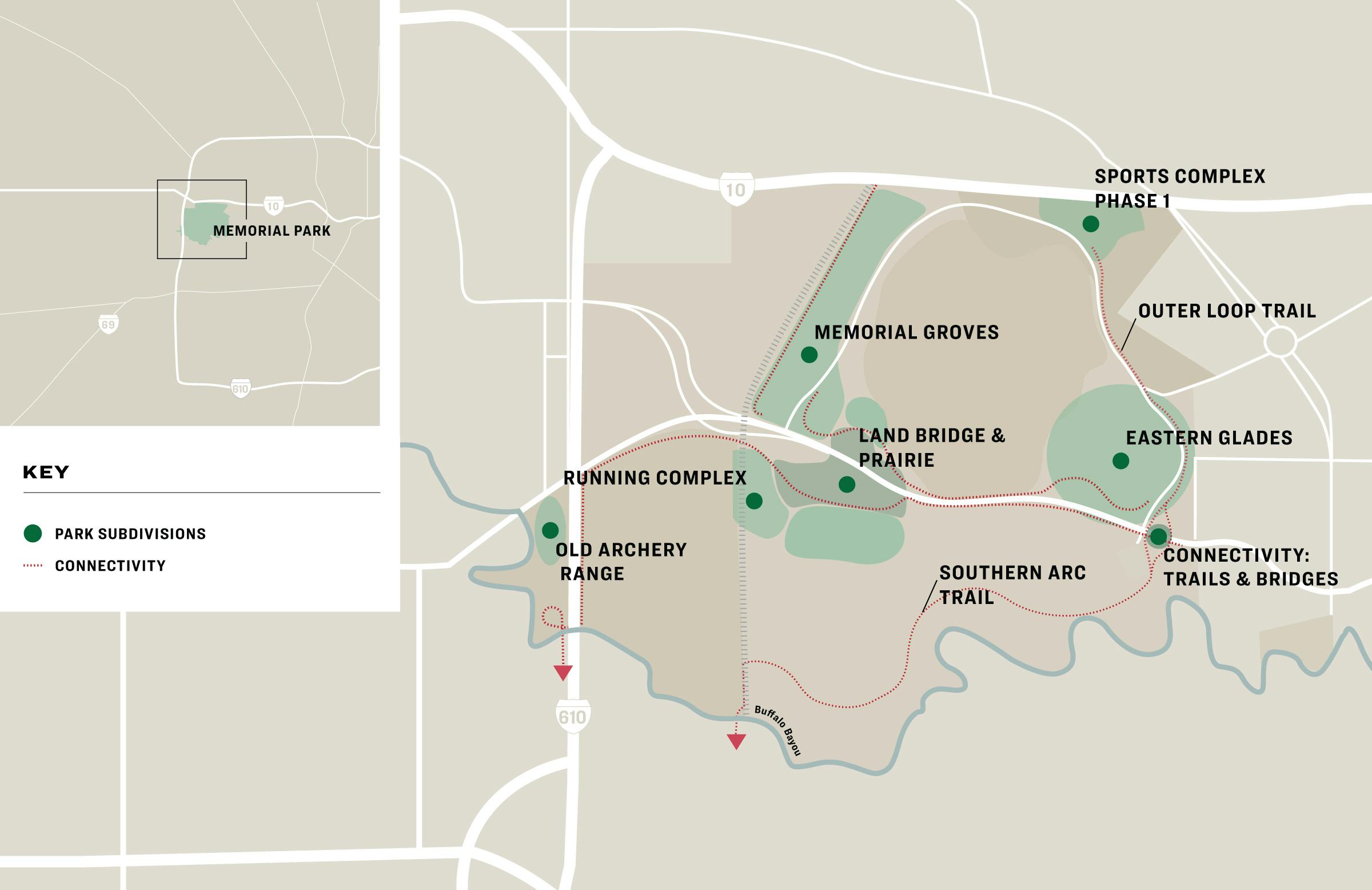

With Woltz, the conservancy engaged in an extensive public study of what Houstonians wanted from the park, and convened ecologists, preservationists, and other experts to determine the optimal use of the land not only for people, but also for native animals and, critically, floodwater management. The result was an ambitious master plan released in 2015. It called for totally reshaping the park, relocating sports facilities, reclaiming native grasslands, preserving parts of Camp Logan, and creating land bridges to reconnect the two halves of the park, which are currently divided by six lanes of high-speed traffic. Success was hardly guaranteed. Ambitious, multidecade plans like these—the conservancy’s full master plan will still have years to go even after the ten-year plan is completed in 2028—have a way of collecting dust on shelves. In 1924, William and Michael Hogg (children of former Texas governor James S. Hogg) sold the land to the city at cost with the stipulation that it be used for a public park, but an original master plan for the land never came to full fruition. In 2018, however, robust support from the Kinder Foundation helped turn ideas into action. Now the park is being reshaped by a plan, set for completion in 2028, that is undeniably transformative.

To be sure, not everyone wants to see Memorial Park’s arboraceous expanses replaced with amenities. “This is hardly an experience of nature, and neither is it environmentally sound,” said Susan Chadwick, president and executive director of Save Buffalo Bayou, a local environmental advocacy organization focused on preserving the tree-lined banks of Buffalo Bayou in and around Memorial Park. “Too much of the park is used for maintenance. Too much of it is blocked off. Too much of it is being landscaped.” From her perspective, the projects mar the park rather than enhancing it. The World War I memorial included in the plan would turn a verdant green space into “a giant cemetery.” The land bridge is a “seventy-million-dollar vanity project.”

That’s not how Woltz sees it. He points to the land bridge as perhaps the most consequential part of the project. Memorial Park is nearly twice the size of New York City’s Central Park, but the current design makes it feel more like an archipelago marred by speeding cars.

So a man-made hill, which is under construction, will connect the north and south sections of the park and hide the traffic in a tunnel covered by a hundred-acre hilltop field. Houston has a long history of paving the prairie. Now the prairie is finally getting the upper hand.

“This new parkland will symbolize the triumph of ‘green over gray,’ healing the divide created by Memorial Drive half a century ago,” said Shellye Arnold, who is president and CEO of Memorial Park Conservancy. (She is not involved with Arnold Ventures, where I work, and whose founders have individually donated to the conservancy.)

It’s a design that fits well with Woltz’s philosophy of parks. In his mind, each should reflect the city where it’s built. Some of the structures in the Eastern Glades are crafted from a pale limestone that evokes Houston’s original civic buildings. The Memorial Groves, a living monument to the soldiers who trained at Camp Logan, transforms a local historic curiosity into a core feature. The land bridge returns Houston’s grasslands to their natural state—even if there is nothing fully natural about the whole thing. The bridge is another of Memorial Park’s wonderful illusions: now you see the traffic, now you don’t.

Woltz describes Houston with an even more optimistic framing than what you might hear from the usual local boosters. In his view, the city isn’t about business, it’s about the land. We’re not a swamp, we’re wetlands. It’s not a bayou, it’s a river. “I really think Houston, instead of a city of oil, should be known as the city of parks,” he said.

The pandemic has also made the project feel more urgent. Now that convening indoors is a health risk, public parks are more than pleasant scenery—they’re a fundamental necessity. In fact, the public health aspect of urban parks was part of their original selling point. Frederick Law Olmstead, who essentially founded the field of American landscape architecture, saw his field of expertise come into high demand as booming Gilded Age cities suffered from outbreaks of cholera, flu, and other diseases. Olmstead argued that parks were necessary to allow city dwellers the “opportunity and inducement to escape at frequent intervals from the confined and vitiated air of the commercial quarter” and to “supply the lungs with air screened and purified by trees and recently acted upon by sunlight.” Today, an ample body of public health research backs him up. Researchers have found that people who live near parks have a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and premature death.

To Woltz, parks also protect more than physical health—they bolster civic health. “Unfettered access for the public to nature is a really important part of the civic rights of Americans,” he argues. Parks are places open to everyone, unencumbered by the visual pollution of modern life, the noise of streetscapes, the demands of a commercial society. I once heard Woltz refer to public parks as the “last democratic place in America where people can be in a public place without feeling obligated to buy a cup of coffee.” Many seemingly public areas, such as downtown Houston’s Discovery Green, are actually under private management—a fact city dwellers learned the hard way when the park banned anyone from playing the mobile game Pokémon Go within its boundaries.

Memorial Park isn’t purely democratic, either. The new park will be free (except for the cost of parking) and fully open to the public, but like any major urban development project, it is the result of years of power brokering, private fund-raising, and negotiation. More than half of the budget is coming from private donors. A quarter of the resources flow from the Uptown Development District and Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone (TIRZ), a board appointed mostly by the mayor that redirects the marginal increases in property tax revenue from the nearby Galleria mall area.

That reliance on private donations to maintain public green space isn’t specific to Memorial Park. Parks of all sizes across the nation depend on conservancies to maintain operations, including several in Houston. In fact, it is increasingly difficult to pay for a park’s upkeep without some kind of support from the philanthropic sector. “I am seeing the public landscape across America suffering from lack of funding,” Woltz said. “We reduce our taxation, and therefore the coffers are quite thin when it comes to tending to the public land.”

The use of a TIRZ, however, adds another complicated layer to Houston’s park planning. These special taxing districts were originally conceived as a way to jump-start development in impoverished neighborhoods, but developers have also used them to further enrich wealthy areas. The construction cranes and high-end condos that line the West 610 Loop belie the idea that the Memorial Park area needs any help spurring development.

What the TIRZ does allow, however, is a way to circumvent the budget process at city hall.

A revenue cap imposed by voters in 2004 automatically triggers tax cuts when the city collects too much in property tax dollars. Public safety and pension costs have a way of siphoning any surplus revenue. Political pressure at city council casts a shadow on spending nine figures on green space for one of the city’s wealthiest areas while so many other neighborhoods lack basic amenities such as sidewalks or flood prevention.

“There’s no doubt the city will always have more pressing issues than redevelopment of parks,” said Charles Blain, president of Urban Reform Institute, a Houston-based conservative nonprofit.

So in 2013, the city council approved a deal that extended the life of the Uptown TIRZ, which was originally scheduled to dissolve in 2029, and massively expanded its boundaries to cover Memorial Park. Now all those pesky political barriers can be easily avoided and property tax revenues can be leveraged to build a park that otherwise might not survive the usual democratic process. Of course, not everyone is comfortable with a public park being planned in part behind closed doors. “We are concerned about the privatization of our parks and parks management all across the city,” Chadwick said. “The Memorial Park Conservancy has no requirement to have open meetings. And quite obviously it now serves as a tool of the Uptown Development District.”

To its credit, the conservancy went out of its way to collect public input on the park design, hosting numerous public meetings to inform the Memorial Park plan. The nonprofit also engages the public “through periodic surveys, meetings with stakeholders, and its annual State of the Park event,” Arnold wrote in an email. The Uptown district, as a government corporation, also has public meetings.

The idea that nature should be free and accessible for every Houstonian to enjoy remains an aberration from the usual order of things in Houston. The municipal parks budget has been in steady decline over the past thirty years. In 2020, the city actually spent $12 million less on parks than did Dallas, which is physically half its size.

In a way, Memorial Park has always been an outlier from how Houston operates. It was sold to the city with the stipulation that it never be used for commercial purposes. Attempts to drill for oil within the park have been thwarted over the years—notably, in a 1976 fight involving Brownco Inc. Since the city’s founding, these 1,500 acres—almost five times the size of Austin’s beloved Zilker Park—have been one of the few places prioritized for the public. Now, at a time when Texas is planning to bulldoze hundreds of homes to expand a Houston freeway, Memorial Park is pushing a street into a tunnel to make more room for people. This isn’t how things usually work in Houston. Maybe that’s what makes it so astounding.

In 1836, a real estate advertisement pitched the new city of Houston as “handsome and beautifully elevated, salubrious and well-watered”—far from the reality of a frontier settlement amid a muddy, mosquito-infested swamp that was routinely beset by yellow fever. The marketer’s image of Houston was an illusion, if not an outright lie.

Take a walk through Memorial Park, however, around the Eastern Glades or down the hilly barrancas that divert rainwater into the bayou, and you start to get a sense that Houston is building the city described in those early ads. There’s clear water, a fresh lake, even rolling hills. Through sheer force of will, those behind the renovation of Memorial Park are crafting Houston as it has always imagined itself. The illusion is becoming real.

- More About:

- Houston