This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Several years ago I received a literary fellowship that included six months’ residence on J. Frank Dobie’s old Paisano ranch west of Austin. I used the time to make some badly needed course adjustments. I started a book, redisciplined my work habits, and regained control of some depletive vices. In the afternoons I ran two miles through the woods to the mailbox, then I snorkeled and fished the emerald pools of Barton Creek. I borrowed some binoculars, bought a copy of Peterson’s Field Guide to the Birds of Texas, dutifully recorded my sightings of loggerhead shrikes and rufous-sided towhees. In a hammock on the old man’s front porch, I even read a bit of J. Frank Dobie. All this was undertaken with a certain droll skepticism, a sense of temporary aberration. I was living out one of the fantasies of my generation, but my lease on Walden Pond expired August 1. After that, I would get back to the land of high-line wires, neon signs, and freeway traffic jams.

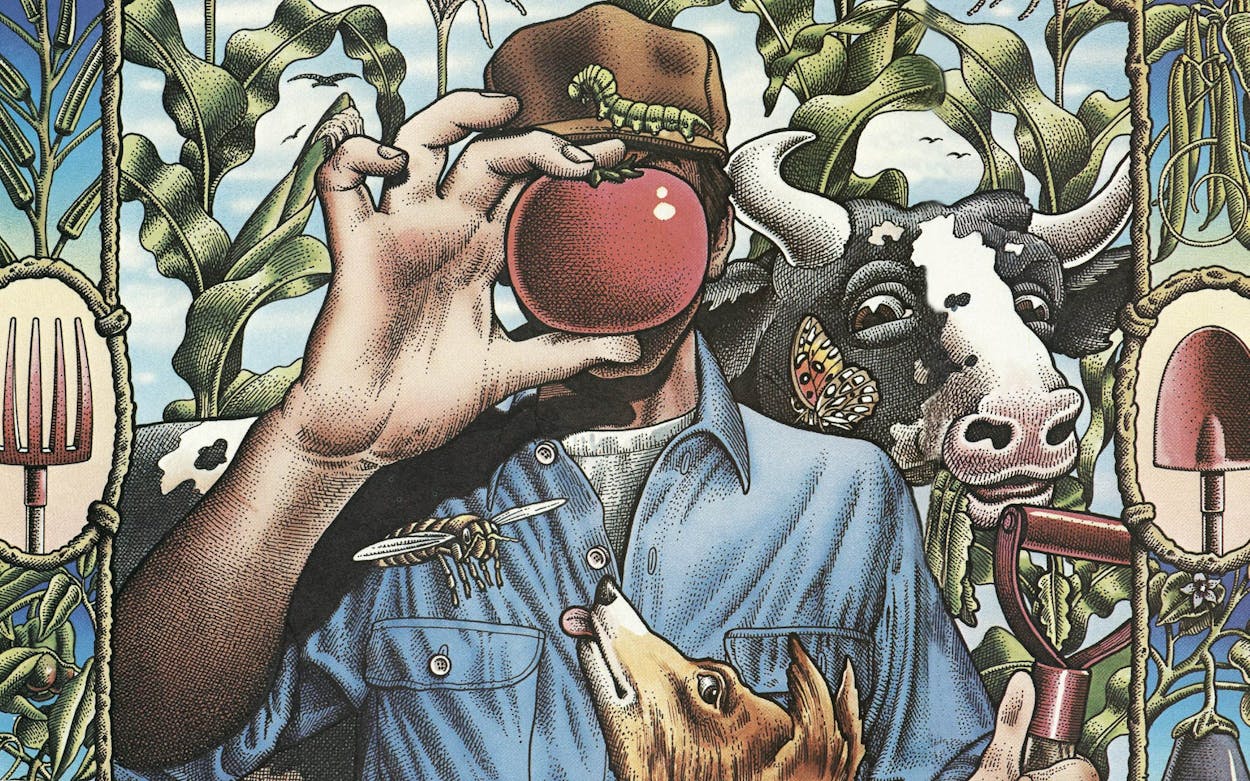

Out behind the house was a neglected garden plot that a previous fellow had impressively fenced, at great cost in labor, to keep the deer out. I admired his prose (somewhat more than Dobie’s), and since the idea of gardening seemed philosophically consistent with my turning over of new leaves, I purchased my first gardening magazine and rented my first Rototiller. On the back cover of that periodical was a photograph that still amuses me: standing between rows of blooming rose plants, a ravishing, braless gardener in tank top and fatigue pants smiled down over the handles of her newest purchase, a two-horsepower Ariens tiller. A more truthful ad would have shown her arms raked bloody by the rose thorns, her dungarees in shreds. Soon I would be bucked and yanked by my tiller, numb to the shoulders, coughing muddy phlegm. For the first time I could appreciate the toil of my grandfather, a tenant cotton farmer who until he was nearly sixty plowed behind the backsides of draft horses and mules. Turning the soil, working it deep, is the most important thing a gardener does, and there’s no joy in it.

Friends who recall that first garden assure me it was a scene of great beauty and culinary bounty. I recollect the boneheaded style of my endeavor. My instincts were organic, of course, as are all gardeners’. Unfortunately, I failed to discern that if a century’s overgrazing hadn’t robbed the ranch of most of its topsoil, all those picturesque brows of limestone wouldn’t have been peeking up through the pastures. The floor of a nearby pen was deep with manure patties from a neighbor’s cattle that occasionally eased through disrepaired fences to munch Paisano’s longer grass. I broke wheelbarrow loads of these chips in organic sacrament and spaded them into my garden. And at last I planted.

All the transplants withered. Only the zucchini seeds came up. The forces of Whole Earth hadn’t told me that it takes roughly fifty pounds of dry manure to produce one pound of soil nutrient. And while the use of chemical fertilizer poses no health hazard for humans, it’s a stopgap measure at best; the artificial nutrients decompose quickly and do nothing for the permanent condition of the soil. But circumstance demanded the fast fix, so I made the next typical mistake. When considering fertilizer, one tends to assume that more is better. Most chemical fertilizers come in fifty-pound sacks, and the instructions on the sack seldom state clearly enough that a hundred-square-foot garden requires two pounds of these chemicals at most. They never say, “Warning: This May Be a Lifetime Supply.” Fried by the overdose, my next installment of nursery transplants gasped and disintegrated into leafy outlines of dry white dust.

Luckily, I had gotten off to an early start, and it rained a lot that spring. I made a garden, but only the zucchini truly thrived. Two fifty-foot rows of it. How was I supposed to know? My previous exposure to summer squash had been limited to a passing interest in the Safeway produce bins and an occasional pot of ham-bone stew. I couldn’t begin to keep up with the garden’s mass production. On the first day of their existence, the finger-size squash were good to eat. On the second, they grew tough and reached the size of large cucumbers. By the third, they were monsters. Toward the end, I came to cheer the invasion of gray squash bugs that stung the beast plants into inactivity. In thick gloves and long-sleeved shirt—the unpleasantness of squash harvest is surpassed only by that of the prickly and caustic okra—I plunged into this jungle, and with grunts of exertion, heaved the rampant zucchini over my colleague’s deer fence. Each had the heft and balance, though not quite the length, of a 36-ounce Louisville Slugger.

I don’t believe in green thumbs: show me the dirt under the fingernails. A garden of any size requires long hours of stoop labor, and while I still had a lot to learn, I discovered that on a given day—Calm down, son, your check’s in the mail—I could be a demon with a long-handled hoe. The immediate reward of that hard and sweaty work was an odd meditative trance. The avocation guaranteed an element of calm and order in a sometimes chaotic routine. My office calendar might reflect harried scribblings of airline reservations, rescheduled interviews, emergency dental appointments, but there in the margin, in a much steadier hand, was the garden reminder. During that week in February, I should plant the beets, the cabbage, the English peas.

As it happened, my experiment in rural lifestyle was no passing fancy. I later found my own country place—a cedar log house on a hill overlooking a long valley that my neighbors, German farmers, called Rogues Hollow. Their tractors growled long into the night; in late June the slopes turned bright sorrel with their contoured fields of ripe maize. Black gumbo soil compacted with golf-ball-size rocks—there was no question of that soil’s fertility, though I shudder thinking of the broken backs of those who had to plow it with mules.

I laid out my garden a few strides from my screened-in porch. One evening at twilight I heard the strangest flapping whisper overhead. En route to summer residence at the Great Salt Lake, interlocking V’s of migrating white pelicans, more than a mile’s worth of them, looped in ponderous and stately procession toward the government watershed lake at the base of the valley. Another afternoon, while I was out for my daily jog, a rare black fox ran across the road in front of me. I raced in joy back to the house, where the radio informed me that the latest maniac had just fired a bullet at the president. Shades of John Denver, I saw my first eagle in flight while I hoed weeds in that garden. It was a lovely, secluded, impoverished time in my life.

The worst money crunch always came in the summer, when I ceased teaching part-time at the nearby state college. There were periods when the garden had to feed me; weeks passed without an ounce of hamburger in the refrigerator. But I knew better than to run those economics through the calculator. Even though I wrote the labor off, if I had added together the water bill, the costs of fencing supplies and the latest necessary tool, and the expense of succumbing to the impulses that always seize me in a nursery greenhouse, frugality would have had me standing in the supermarket checkout line instead of in my garden plot. The quality of the temporary vegetarianism was my reason for gardening.

As long as the vegetables taste right, home gardeners don’t particularly care what they look like. If the potato has a dark spot, that can usually be corrected with a paring knife. Wholesale buyers of supermarket produce know they won’t get that break from consumers. Commercial growers thus rely on hybrid strains that attain, then hold their picture-perfect color and shape through the rigors of transcontinental shipping. So we buy gorgeous table grapes that won’t spurt juice even if stepped on, tasteless tomatoes of papery texture that Safeway slips by us with the euphemistic “Firm—for Slicing,” and the creepiest of the showcase ruses, those cucumbers and rutabagas that come dipped in wax. I’d just as soon handle the toe of a pickled cadaver. Through most of the year, with certain vegetables, I can make the earth do better than that.

Even at the height of such scorn, home gardeners rely on the knowledge and resources of commercial agriculture. Our own empirical data do not tell us to plant our autumn Swiss chard as early as twelve to sixteen weeks before the first frost. When I moved to Rogues Hollow, one of the first calls I made was to the county’s agricultural extension agent. (Of the calls received in these offices—a service of Texas A&M—80 per cent come from home gardeners; in most of the large urban counties, the staff includes a full-time horticulturist.) The agent said that on the average I could anticipate first and last frosts on November 10 and March 15, leaving a 240-day growing season. That’s the luxury of gardening in Texas. With very little extra effort, it’s possible to grow and harvest three overlapping but distinct gardens in a single year.

But the Sunbelt exacts its own hungry price. Because most of the frosts are light, the ground seldom freezes, and more insects and larvae survive the winter. With the prolonged food supply, insect populations increase geometrically. We not only have more insects than the Frostbelt, we have more generations of insects. The spring broccoli in my garden at Rogues Hollow was a very pleasant surprise. I didn’t think the nursery transplants would like the coarse and poorly drained soil or be able to withstand the heat so long. I steamed the young heads, buttered them, substituted the tender leaves in recipes that called for greens or cabbage. Then one morning I walked out and found the leaves of every plant riddled with holes the size of buckshot. I never would have dreamed that growing vegetables would challenge my sense of social conscience. I was face to face with yet another loss of youth’s ideals. If I let that go on one more night, my broccoli plants would be reduced to gnawed green stumps.

Organic gardeners contend that even EPA-approved garden poisons can threaten the health of humans. More likely, they just make the gardener’s situation worse. Insects combat chemical warfare by inbreeding resistance to the poisons, and genetic superpests can result. In the garden, insects tend to attack weak and struggling plants. By using proven organic methods to enrich the soil and strengthen root systems, the gardener enables his flourishing plants to shrug off insects. The Organics observe that one Baltimore oriole consumes seventeen caterpillars a minute; over a three-month period, one toad devours 10,000 insects. Cardboard toilet-paper spools worked into the soil around tomato plants hold cutworms at bay. Bothersome slugs crawl happily into a pan of beer and promptly drown. And in dire emergencies, there are natural, biodegradable alternatives to the industry that gave us DDT: soapsuds, nicotine sulfate, the dust of a poisonous daisy called pyrethrum, and the newest panacea, trichogramma wasps, whose larvae develop in and devour the eggs of insect pests in stupendous quantities.

On the other hand, I tend to seek practical advice from the state Agricultural Extension Service of Texas A&M. While concurring that healthy plants are the most resistant to insects, the Aggies go their own way, dusting plants with Sevin, the carbaryl that succeeded DDT: those other folks can feed the little buggers if they want. In the best example of this ideological tension, Aggie horticulturists are particularly fond of debunking the Organics’ reverence for marigolds. While the pungent yellow flowers are alleged to repel Mexican bean beetles and some varieties of tiny, root-stinging nematodes, they also serve as host plants for Texas’ most destructive garden pest, the spider mite. Close relatives of the blood-sucking chigger, spider mites extract their dietary juices from the plant tissues of tomatoes, beans, cucumbers, and eggplants, among others. “Picture yourself with fifty thousand chigger bites,” one extension agent told me. “You get the general idea.”

But the Organics claim the moral imperative, and they never let up. The prophets of Whole Earth are like the old Barry Goldwater campaign slogan: In your heart, you know they’re right. Still, something in the manner of these latter-day saints always puts me off. All gardeners are know-it-alls, but the other side of that nature is amiable and inquisitive. Conventional gardeners think they can learn something from their neighbors’ triumphs and catastrophes. They’ve heard of the Tigris and the Euphrates. They know they didn’t invent the process. As for my own straying from the fold at Rogues Hollow, I claim the defense of relativity. Though I was delighted to learn I had left that slumlord, the squalid cockroach, behind in urban haunts, the sheer numbers of critters out there in the natural world staggered me.

The same spring that I saw the pelicans, the black fox, and the eagle, I also had to give up walking the woods because of the swarming ticks. I killed three rattlesnakes within a horseshoe toss of my front porch. I left the door open for my pets, and one night while I was gone a skunk ambled into the kitchen. My dog held her nose, bared her teeth, and did her duty. Sometimes a scorpion would lose its footing on the ceiling, and a little plop of terror would land on the quilt Granny had fashioned from my baby shirts. I drenched every crack and cornice of my abode with Diazinon. If that cost my garden a few pollinating honeybees, they should have stayed outside where they belonged. In that frame of mind, counterattacking the cabbage loopers on my broccoli leaves with 5 per cent Sevin dust seemed no great shakes. I had developed a case of the gardener’s peculiar and incessant paranoia: the entire chain of being was out to rob the fruits of my honest labor. Bugs were one thing, but my worst garden enemy was the ubiquitous Black Cow.

If you can’t eat cattle or sell them, they’re nothing but trouble. Breeders of Angus cattle dismiss these charges as contemptible slander, but I have it on the authority of my own observation, verified by my North Texas brother-in-law. “Oh yeah,” he told me, “black cows are death on gardens. They’re known for that.” The cattle and I lived in grudging partnership on those acres of sticky gumbo. The landlady lived in the city, I paid monthly rent, and a rancher leased the grazing rights. My contact point with the forces of animal husbandry was Ronina, the rancher’s niece. I knew right away that I wanted to get along with Ronina; she had a loaded .22 pistol in her hip pocket. But I had increasing difficulty admiring the attributes of her minions. One hot summer day I was fishing in the stock tank. A cow came to the bank, waded far out to cool off, drank long and deep, threw back her horns, and with a moo of great satisfaction splashed urine into her own water supply.

Without question, I sowed the seeds of destruction in my garden by planting corn. No matter how good it looks in the supermarket, corn is fresh only if you break it off the stalk and carry it straight to the boiling water; the kernels’ chemical conversion of sugar to starch is almost immediate. But for most gardeners, corn consumes more space than its production is worth, and no matter how much mineral oil or Tabasco sauce I pour on the silks, in the end I always peel off the shucks to find the foul mush of a well-fed earworm. And cattle will walk through fire to get at corn. They turned my first two garden fences—tight barbed wire, corner posts set in concrete—inside out. I trained my dog to chase off any large animal that set hoof on our hill. That worked with the deer but not the cows. I fired my .410 into the air to scare them away. I lofted a few arcs of that buckshot, which, I hope, stung their withers. They stared dully and chewed their cuds, waiting.

One morning I awoke to find a Hereford calf gamboling in my garden, enjoying my offering of corn. The calf reacted to my bellow with the surprise and injury of a reprimanded child, then cleared the fence with a nimble kick of its heels. I could no more have exacted vengeance from that creature than I could have fried the backstrap of Bambi. But the black ones were devious, calculating, vile. At night when I drove up to the house, a very hoarse collie greeted me with great anxiety; I saw the evil shadow slip around the corner of the screened-in porch with a supremely contemptuous flip of the tail.

I thought I had solved the problem when I installed a single-strand electric fence. Once they get the juice, cows usually stampede forward, breaking the circuit and tearing down the fence. But the simple design and repair allow for that contingency, and few cows come back for a second helping. Now I faced only the menace of the cottontail rabbits that were in love with my English peas. That’s easy, a friend suggested. Just lay out a stripe of bone meal all the way around the garden. “What do you mean, they won’t cross bone meal,” I scoffed. “They forget how to hop?” It worked because of the smell; this I established when my cat, one of the least olfactory of creatures, jumped back from the powder as if he had just taken a draft of ammonia. At last I could sit back and watch my garden grow.

But the rancher kept changing the herd on me. Every other week three more cows had to test the fence. If I happened to be gone at the time, that would just be too bad. Out dove hunting one afternoon, I walked up the slope and saw that particular black cow, my nemesis. Ignored by the dog, whose spirit on this issue was clearly broken, the cow and her calf grazed the garden boundary of Johnson grass. With a clumsy—or deft—move of her hip, the cow bumped her own offspring into the wire. The calf thrashed wildly, bawled to blue heaven—and removed the only obstacle to those knee-high stalks of sweet corn. You take the volts, kid.

On the worst morning of my entire gardening experience, I fumbled at the latch of my gate. I had a roiling stomach, bleary eyes, a bad head full of urban debauchery. As I drove up to the house, a red-tailed hawk passed before me with a soothing, reassuring cruise. But the scene in front of the house took my breath away. The fence was down, of course. The cow had razed the corn and finished off the English peas, but apparently nothing else had suited her appetite. So she had stripped my broccoli and tomato and bell pepper plants, stepped on them, broken them, splashed them with excrement. The current ascendant star in my fall garden was butternut squash. Though vines of winter squash cover a lot of ground, the infant fruit of the yellow-meated butternut surpasses any of the spring varieties in boiled flavor; then it matures into the light-bulb-shaped gourd, good for baking, that keeps through the winter. The cow had sampled each of these, then spat out the broken gourds. She had pulled down the tops of the okra plants and splintered the stalks to the wood. My garden was gone. Wiped out without a trace.

A few hundred yards down the fence line, the cattle milled about on the site of the weak and shallow waterline connection—which their weight broke with great regularity, running up my bill and testing my skill as a plumber, always in freezing weather, but that’s another story. Out of ammunition, having used my last shotgun shell a few evenings before in a stirring twilight bout with a rattlesnake, I kicked the cat away from my ankles and yanked open the door of the toolshed. With the collie bounding at my side—this was great fun—I stalked down the slope with a ten-pound sledgehammer and murder in my soul. There’s a line in a novel that I admire, All the King’s Men, by Robert Penn Warren: “We were something slow happening inside the cold brain of a cow.” But the black cow was smart enough to recognize a madman when she saw one coming. She left her calf to its fate without a glance. I had them trapped in a corner of the fence. As I worked through the crossbreeds and the Herefords, the black cow made a low, uneasy sound and cut her eyes in both directions. The drama of a bullfight, played out in reverse. Gripping the handle of the sledge, I cried out and made my move, but she looked one way and juked the other: the mighty swing and miss carried me headlong into the barbed-wire fence.

The time comes when pastoral idyll gives way to considerations of schools, commuting distance, career ambition. Last year I married, moved back into the city, and assumed I had left vegetable gardening behind, if for no other reason, because the property on Possum Trot—always that overweening rusticity of Texas subdivisions—was too heavily wooded. Sunlight is the one deficiency that gardeners can’t overcome. But that spring when the weather turned warm, my wife was out raking leaves and planting bulbs, and I found myself uprooting the grass and spading the soil of the one five-foot triangle, at the corner of the driveway and the curb, where I might have a chance.

I didn’t want much. Three or four tomato plants, some basil and dill. Even at that, the odds were long. Tomatoes require at least 60 per cent of the day’s direct sunshine, and the shade of the tall cedar reached the tiny garden shortly after noon. My neighbor, whose ornamental shrubs and flowers are for me a source of great wonder and mystery, came across the street with a little sack of five-ten-ten tomato food that had gone to waste after her unsuccessful attempt. She came back in June when I was picking my tomatoes ripe off the vine. “Nobody in this neighborhood’s ever been able to grow tomatoes,” she smiled and cheered.

Nice of her to say it, but she’s wrong. There’s a great backyard garden over on Twelfth Street and another one on Norwalk—my favorite: it’s laid out with a fine ironic view of the Safeway store. That yard even has a grape arbor and a purple martin house. One day I saw the woman who lives on Norwalk pushing her husband’s wheelchair down the side street so he could see the garden. I know those people. They hark back to days when the most desirable property came equipped with a root cellar and a canning porch. They’re contemporaries of my grandfather, who retired off the farm and lived out his last years tending a huge garden in Henrietta.

That old man was reason enough for me to take up gardening; for the first time since I was a kid, I had something to talk to him about. One day I gazed out his living room window at about half an acre of collard greens. There wasn’t a weed anywhere. I asked him how he managed that without using mulch. “Why, I never let anything go to seed!” he proudly said.

He raised that garden the way his immediate forebears farmed the American West—long, straight rows; the more space, the better. Hours of labor were no object. And if you overproduced, you shared with the neighbors, then you canned those collards. They’re still good! The urban gardener seeks new alternatives. The Organics promote a component of the French intensive method called double digging. Working the soil two feet down enables root systems to go deep instead of spreading out, which means more plants can be squeezed in. With this method, they contend, a three-foot-square garden is big enough to harvest a variety of desired vegetables. I’ve got more space than that, but this spring I think I’ll try it. I understand now that I need to garden. It’s the gentlest, most intelligent thing I know how to do with my hands.

In January I was under pressure to tear down those ragged old vines that had survived the heat of August and set quite a few blooms in the fall. The tomatoes ripened too slowly because the sun had moved to the south and left the plants in almost total shade. Yet the mildness of the winter had been ridiculous, and with each predicted light frost I brought the ripest tomatoes in to finish on the window shelf and covered the rest with tarps and plastic. “They’re mealy,” said my wife. “I don’t think it’s worth it.” This from a woman who once sent off for boxes of ladybugs and praying mantises, who walked into a feedstore in Pasadena and asked the whittlers where they kept the borage, who insisted on space in my cramped garden for her stand of zinnias. Oh, well. I’m sure I can learn from her.

“Yuk,” exclaimed my stepdaughter at the supper table. “These tomatoes are terrible. They look terrible.” I suffered these indignities in genial silence. The kid was right. Because I had never gotten the hang of watering a garden, my tomatoes suffered from blossom-end rot. I was a lazy gardener last year. I can do much better; in my dream garden I already have.

In that ideal world, the sun, plants, and bugs behave the way the Organics say they should. The shade of a tree reaches one corner of my garden early in the afternoon. These cooler beds contain my De Cicco broccoli and a handsome shrub of French tarragon (available only as transplants; seed catalogs push the fraudulent Russian variety, as flavorless as vodka). Aphids in search of my romaine lettuce—which best resists the Southern sun’s urge to rush it to seed—recoil from the interspersed chives. Beyond the shade, my red onions reinforce this line of defense. Closely interplanted nearby are two more stars of my palate, speckled lima beans and Red Lasoda potatoes. These natural companions discourage each other’s most pernicious enemies—Mexican bean beetles and Colorado potato beetles.

Alongside, a bed of eggplants invites the potato beetles to dine here and leave the less hardy vines alone. The “trap crop” is more expendable because of kitchen limitations; a little eggplant parmigiana goes a long way. But with their velvety leaves and drooping lavender flowers that produce the sensuous blue-black fruit, eggplants are the ornamental prima donnas of my garden. A neutral barrier, they also stand here to appease the caged Burpee Pickler cucumbers interplanted with companion dill and more bushes of speckled limas. Vegetables, like humans, are terrific snobs. Cukes like beans but associate their fears of disease—phytophthora, or late blight—with the dastardly potato.

As for the surplus of speckled limas, there’s no such thing. Though hard to shell, baby limas are simply the tastiest bean in cultivation. I won’t bother to pick more green than I have time to shell. Left on the vine, they harden and deepen in glossy brown color till the sun-bleached pods crack open. Soaked overnight, then cooked with a little bacon and tarragon, these speckled limas taste even better than the fresh variety. Hands down, they’re the best dried beans for the winter cabinet.

On opposite ends of the cantaloupe beds are my green bell peppers and Long Red cayennes (whose taste and reliability I find superior to the region’s more chauvinistic jalapeño). In the fullest sun, beyond the pepper and melon beds, is the hallowed shrine of my symbiotic masterpiece. While the parsley attracts the pollinator honeybees, the sweet basil repels mosquitoes and flies, and both herbs impart vigor to my tomatoes and asparagus. Solanine in the tomato’s leaves and stems repels asparagus beetles. According to the Organics, asparagus protects tomato roots from nematodes. But flavor, not these minor conquests of nature, is the primary reason people garden. Our taste buds make basil the tomato’s perfect herb companion. Substitute basil for lettuce in a sandwich with mayonnaise, crisp bacon, and sliced tomatoes; you’ll never go back to the standard BLT.

For that pleasure I must await the ripening of my caged Better Boy and Bigset tomatoes, but meanwhile the first shoots of asparagus have stemmed up through the mulch. The existence of this bed implies ownership of the ground I have tilled. Asparagus was introduced to this country by the Puritans, for whom it was the perfect crop, and a well-maintained bed of it can produce for up to fifty years. Unfortunately, the maintenance starts with the digging of a trench a foot and a half deep and never gets much easier than that. And even if you start with year-old transplants, establishment of the perennial fern requires a wait of two years before the first harvest. As a renter with an unpuritan approach to manual labor and a reformed chain smoker’s need of oral gratification, I never thought I’d be in one place long enough to justify the wear and tear on my spading fork. But finally the time has come. This gardener has paid his dues. I caress and pluck the first tender spear. Oh, go ahead. It’s been two long years. I bite the raw asparagus just below the lovely tip. Ah!

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Cattle

- Austin