The last time I was in this part of Palo Duro Canyon, the authorities were after me, for all I knew with dogs and helicopters. That may be overstating the case, but there were helicopters overhead, and my backpacking companion and I were certainly paranoid that the law was on our tail. We were trespassing—heinous and despicable behavior for which we would eventually be arrested and receive our official comeuppance. But this was back in 1987, when the only way to see this stretch of the canyon was to park alongside Texas Highway 207, duck under a barbed-wire fence, and walk across the plains for three days hoping no one saw you.

Now, twenty years later, I was confessing my crime to Doug Huggins, the assistant superintendent of Palo Duro Canyon State Park, which had recently undergone a dramatic and long-awaited expansion of its boundaries. Between 2002 and 2005, the park made two major acquisitions—the 2,036-acre Cañoncita and 7,837-acre Harrell Ranch properties—bringing its total acreage, which had languished for decades at 16,402, up to a healthy 26,275. Among the new lands was the site of my clandestine visit. But I didn’t tell Doug a few of the more incriminating elements of that story, since however sympathetic he seemed, his pickup did say “Police” on its doors.

“Actually,” he told me, “people used to do that quite a bit.”

It’s not hard to understand why. Contrary to the perceptions of many who travel it, the Panhandle is not an endless, flat plain. It actually possesses one of the most shocking moments of yin-yang landscape variation on the continent. What everyone groans at is the top of a mesa so vast that when young Georgia O’Keeffe saw it for the first time, in 1914, she immediately pronounced it the biggest single thing she had seen in her life. But that tabletop has an edge running nearly three hundred miles north and south, an escarpment where the ground suddenly falls away in a series of trapdoors to reveal hidden worlds. The effect is as confusing as a mirage, like stumbling baffled into a brightly hued mountain range in the middle of the Kansas wheat fields. Plunging as deep as one thousand feet below the flat, dull plain is a roar of color and form, a profusion of canyons carrying the headwaters of most of the major rivers that flow across Texas—such a canyonated tangle, in fact, that the Environmental Protection Agency in 2004 proclaimed it one of the state’s distinct eco-regions, the newly christened Caprock Canyons, Badlands, and Breaks.

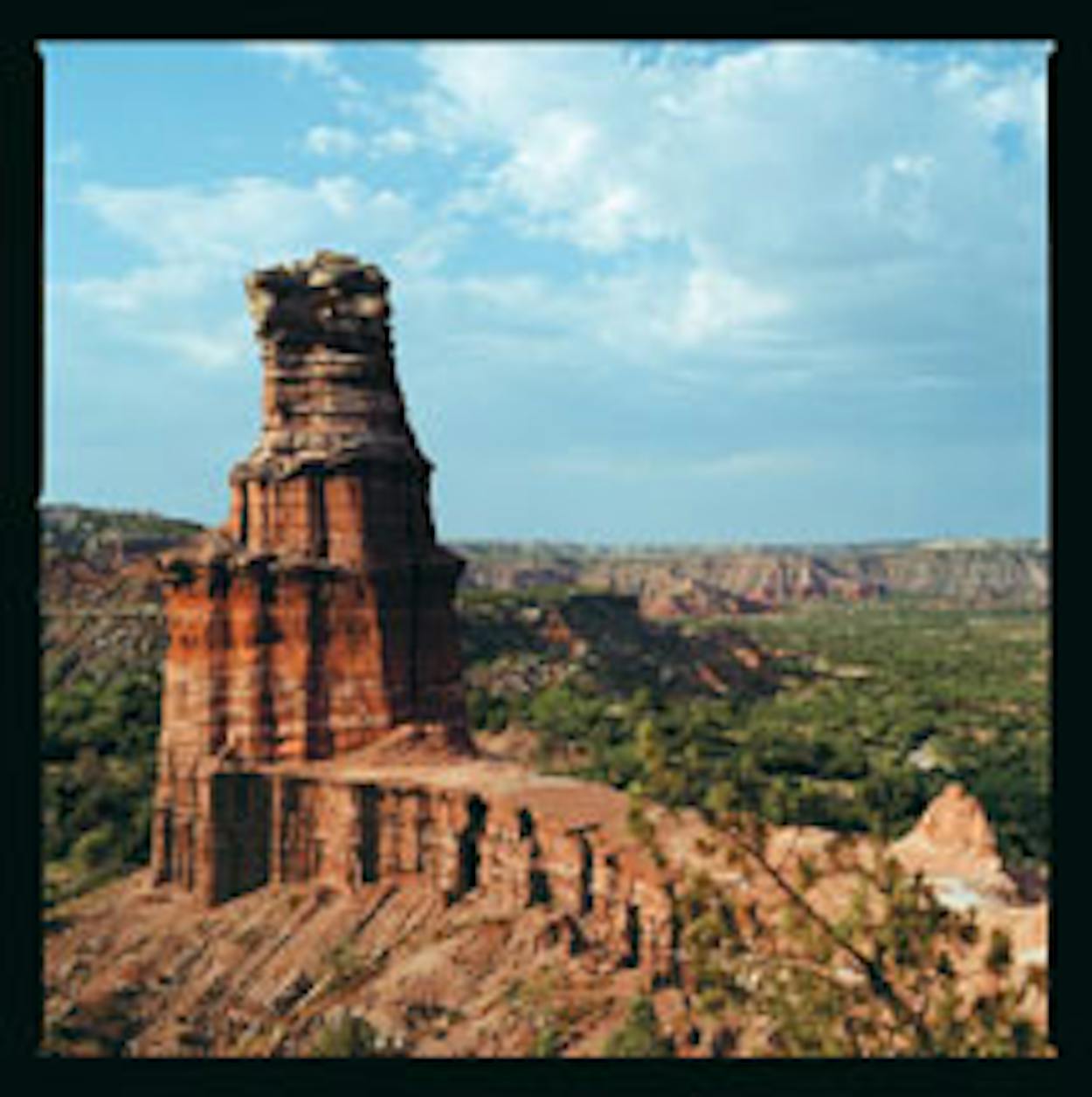

The primary star in this constellation has always been Palo Duro Canyon, a fifty-mile-long technicolor trough of slot canyons and gorges diving through Triassic sandstones. Carved by the Prairie Dog Town Fork of the Red River over millions of years, the canyon’s ecology runs the gamut from relict mountain juniper forests to desert badlands. This natural wonder has very likely been astonishing and delighting humans for 12,000 years, but over the past 150, private ownership severely curtailed which portions of it we were legally permitted to enjoy. O’Keeffe once called Palo Duro her “spiritual home.” In Texas, the trouble with making any natural landscape your spiritual home is that there may come a time when there’s a fence around it. Though Palo Duro has been partially accessible to the public since it was established as a state park in 1934, within its expansive watershed the park enclosed fewer than 17,000 acres. And with only this fraction of the total canyon in its possession, Texas Parks and Wildlife opted to manage Palo Duro like some kind of Panhandle amusement park, complete with railroad rides, car camping, and summer performances of Texas, the hokey historical laugher of a melodrama.

The problem began with annexation, in 1845. For a variety of stand-alone reasons—among them U.S. reluctance to assume the foreign debt the Republic of Texas had run up in wars to drive out Indians and Mexicans—Texas, unlike every other Western acquisition, got to keep its public lands, which it proceeded to dispose of in an orgy of surveying and selling, acquiring and privatizing. The state got railroads, canals, and an operating budget and in the process turned property ownership into an eleventh commandment. Like almost every other square foot of Texas, Palo Duro passed into private hands.

When the National Park Service did its first round of evaluations of potential sites in Texas in the early thirties, Palo Duro—with its small state park already in place—was on the docket to become a million-acre “National Park of the Plains.” During a 1934 tour, the NPS’s Roger Toll, who literally laid out the state’s future with recommendations for parks in Big Bend, the Guadalupe Mountains, and Padre Island, spent four days in Palo Duro. His escort was the rabidly anti—New Deal Panhandle wing nut J. Evetts Haley, who was beyond ironic as a choice for a guide, akin to having Dick Cheney deliver Al Gore’s global warming slide show. Disappointing NPS ecologists, who had hoped to create a kind of Great Plains Yellowstone around Palo Duro, Toll’s report concluded that with the Grand Canyon already protected, a national park at Palo Duro would be redundant.

But the NPS was still interested in Palo Duro, and a few years later, in 1938, it sent a team that recommended a less visionary but still whopping 135,000-acre national monument. These were privately held lands, however, and the NPS had no acquisition budget. The strategy then working in states like Maine, South Carolina, and West Virginia was to conduct citizen drives and ask wealthy benefactors for help. Yet while contributions for a Palo Duro National Monument poured in from places as distant as Denver, Albuquerque, and Oklahoma City, Texans seemed singularly unmoved. The funds never materialized. (A similar state campaign on behalf of the park in Big Bend, led vigorously by Amon Carter and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, netted all of $8,346.88.) As Justice William O. Douglas would later observe in his 1967 book Farewell to Texas: A Vanishing Wilderness: “There are hundreds of millions of dollars in Texas for the promotion of right-wing political and educational programs, but not many dollars for private ventures to save pieces of our outdoor heritage … (A park is socialism, isn’t it?)”

For decades the huge bulk of Palo Duro Canyon remained in the hands of a few ranching families (one of Texas’ signature features, the butte known as the Lighthouse, was not in the original park but got added in the sixties). Then, in the seventies, the TPWD purchased a couple of private ranches 45 miles south of Palo Duro to get hold of another vivid pair of canyons. Caprock Canyons State Park, totaling just under 14,000 acres, was also within the Red River watershed, and some of us immediately saw the possibility for something big: Couldn’t we fill in that lost world of canyons along the 45 miles between the two parks and create the National Park of the Plains that never was?

Fifteen or so years ago, in Caprock Canyonlands: Journeys Into the Heart of the Southern Plains, I suggested a federal solution. Having unearthed the story of the failed national park at Palo Duro while researching the book, I argued that the NPS, which was publicly lamenting its lack of Great Plains parks and casting about for new possibilities for plains wilderness preservation, ought to reopen its half-century-old files on the Palo Duro Canyon system. Apparently I was almost the only person in the state who thought so. A TPWD official told me that, frankly, any proposal combining the words “Texas,” “wilderness,” and “Washington” in the same sentence was worse than a nonstarter: It might get you excommunicated as a Texan.

Okay, so now I see the light. This is how you do it—piecemeal and by the state of Texas, which no one has ever accused of having a socialist bone in its body. By quietly having a standing offer ready, a state department long criticized for its reluctance to add public lands has pulled off a coup. The Harrell Ranch and Cañoncita additions have created the possibility for a true wilderness area on the Texas plains. The transfer features a continuing grazing lease for the Harrells, so the riparian lands, which are pretty cowed up, will probably remain so, but the upland areas are in good shape. Despite a bit of ancestral infamy for the Harrells, a couple of whom knowingly killed the last Plains buffalo wolf in the Panhandle, the family has done reasonably well by the canyon. They took good care of the historic site of the 1874 Battle of Palo Duro Canyon, which, absurdly, had never been part of the park. That site marked the end of Indian life on the Southern Plains just as finally as the Little Bighorn site did on the Northern Plains (the latter, by the way, is a national monument).

Almost as soon as I heard about these new acquisitions, I called Doug Huggins to inquire if I might see them for myself. Palo Duro Canyon isn’t just Georgia O’Keeffe’s spiritual home. It’s close to being mine too, and twenty years after I’d had to trespass to experience it, I thought things might be looking up for having a new kind of relationship with this bright, bold country. Although the new Palo Duro additions are still closed to the public while the park develops a trail network and backcountry campsites, Doug kindly offered to give me a tour. Between big snowstorms this past January, my Alaskan malamute, Chaco, and I drove over from Santa Fe, hoping to see something like my old pet vision of a national park in the Panhandle.

We spent our first afternoon exploring the Cañoncita addition by pickup. Not only does it add more than two thousand acres along the southwest side of the park, but it includes the Gilvin family homesite, a stunning location on the lip of the canyon. Though it’s considerably smaller than the Harrell addition, Cañoncita is nonetheless a critical piece, draping from the canyon rim down across the mouth of the beautiful side gorge of North Cita Canyon. Until hiking trails go in to connect the original park with the Harrell Ranch acquisition, Cañoncita provides the only route into the new parts of the park.

After a night in the nearby town of Canyon, I joined Doug and his natural resources manager, Matthew Trujillo, on a spectacular winter morning for the real treat, a return to my illegal 1987 campsite. We were just a few feet from the gurgling Red River, in the very location where Comanches, Kiowas, and Cheyennes made the last grand Plains Indian encampment in Texas history that fateful September in 1874. By four-wheeler and foot, we spent most of the day traversing the Harrell Ranch acquisition, working our way into, and then back out of, deepest Palo Duro. In many respects the park will be completely remade by the addition of these lands. Finally, it will begin to seem wild, full of bobcats and turkeys slipping away through the mesquite and grama grass, and bands of mule deer bucks strung out in silhouette across the mesa tops, and slate-headed bald eagles looping in the blue above, and behind it all the amazing lavender, saffron, chocolate, and brick-red badlands known as the Spanish Skirts providing a backdrop unlike anywhere else on earth.

Maybe, as Justice Douglas joked, a park really is socialism, but if so, it looks awfully good on Palo Duro. The experience of being down in the canyon’s core, with its riot of colors and its bountiful wildlife, was a reminder that outside of Big Bend, there is just no other big Western setting in Texas like this. The Harrell Ranch and Cañoncita additions are a start, but continuing to expand the park presence here in the Panhandle should be central to our vision of place. If the state wanted to, it could keep up the piecemeal process, adding more and more land, especially down the western watershed of Palo Duro. There lies the primary wilderness canyon country of the Texas Panhandle—marvels like the Mexican Creek and Barrel Creek canyons; or Indian Creek Canyon, which the Nature Conservancy has been trying for years to acquire; or the stunner of the High Plains, Tule Canyon, mistaken by General Randolph Marcy during his 1852 expedition as the source of the headwaters of the Red River. The Narrows of Tule Canyon is a Great Plains version of Yosemite, and in any public-spirited society it would belong to the people of Texas.

Like Harrell Ranch and Cañoncita, all this country could be ours and damn well ought to be. The plains may be on their way to becoming a sacrifice area of hog and wind farms, but for some of us there will always be the need to develop a tie with the real world underfoot—those Contact moments with sky, earth, and sun. Soon, for the first time in our time, there will be country enough for an authentic wilderness experience in the Panhandle, a stunning, unfenced expanse of Western canyon lands for channeling our inner bonobo, or at least our inner Roy Bedichek.

Imagine doing that in Texas … and not getting arrested.