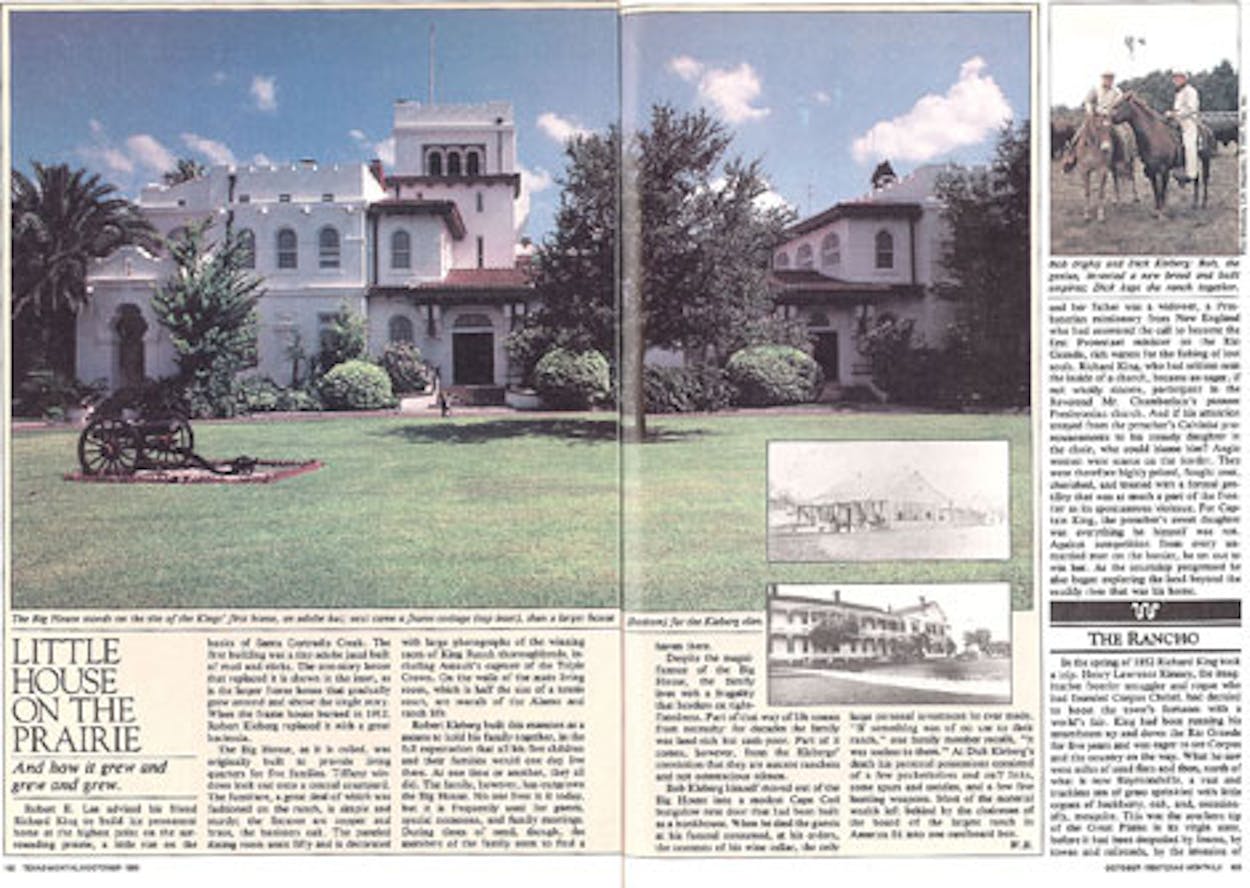

Robert E. Lee advised his friend Richard King to build his permanent home at the highest point on the surrounding prairie, a little rise on the banks of Santa Gertrudis Creek. The first building was a tiny adobe jacal built of mud and sticks. The one-story house that replaced it is shown in the inset, as is the larger frame house that gradually grew around and above the single story. When the frame house burned in 1912, Robert Kleberg replaced it with a great hacienda.

The big house, as it is called, was originally built to provide living quarters for five families. Tiffany windows look out onto a central courtyard. The furniture, a great deal of which was fashioned on the ranch, is simple and sturdy; the fixtures are copper and brass, the banisters oak. The paneled dining room seats fifty and is decorated with large photographs of the winning races of King Ranch thoroughbreds, including Assault’s capture of the Triple Crown. On the walls of the main living room, which is half the size of a tennis court, are murals of the Alamo and ranch life.

Robert Kleberg built this mansion as a means to hold his family together, in the full expectation that all his five children and their families would one day live there. At one time or another, they all did. The family, however, has outgrown the Big House. No one lives in it today, but it is frequently used for guests, special occasions, and family meetings. During times of need, though, the members of the family seem to find a haven there.

Despite the magnificence of the Big House, the family lives with a frugality that borders on tight-fistedness. Part of that way of life comes from necessity: for decades the family was land-rich but cash poor. Part of it comes, however, from the Klebergs’ conviction that they are austere ranchers and not ostentatious oilmen.

Bob Kleberg himself moved out of the Big House into a modest Cape Cod bungalow next door that had been built as a bunkhouse. When he died the guests at his funeral consumed, at his orders, the contents of his wine cellar, the only large personal investment he ever made. “If something was of no use to their ranch,” one family member recals, “it was useless to them.” At Dick Kleberg’s death his personal possessions consisted of a few pocketknives and cuff links, some spurs and saddles, and a few fine hunting weapons. Most of the material wealth left behind by the chairman of the board of the largest ranch in America fit into one cardboard box.

- More About:

- King Ranch