This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I have never heard of a swimming hole on the Red River. No canoeists navigate its rapids, and no college revelers float by in cutoffs and inner tubes, towing coolers of beer. Through seasons wet and dry, with rare exceptions it runs the color of chocolate milk, and it smells bad. Unlike our sightlier streams, it never washes clean over beds of limestone, granite, or gravel. To love this body of water, you have to forgive its ugliness and work your way forward from there.

Nevertheless, a richly layered mythology has grown up around this muddy and moody waterway that separates Texans from Oklahomans east of the Panhandle. Part of the romance of the great American West, the Red River has inspired cowboy ballads, scores of historical novels, and some choice westerns. In Howard Hawks’s 1948 classic, Red River, John Wayne drives nine thousand head of Texas cattle north toward the nearest railhead. Spurring his horse into the shallows of that river of promise, of starting over, the big trail boss points at clear pools and warns the drovers of quicksand. At a signal, cattle crowd down the grassy slope and wade into the Red with scarcely a splash; they don’t get their noses wet.

But the scene—it was filmed in Arizona—completely misses the power of its title stream. The Red was the bitch river—the moment of truth and the psychological point of departure. South of it, trail drivers endured the resentment of farmers who did not want a million hoofprints in their fields. North of it, they encountered bands of Comanches and Kiowas, who were openly hostile in the early years. Later, when theoretically pacified on the reservations, the Indians extorted beefs of tribute, which they called “wohaw.” Trail bosses tried to give them cripples. And the river showed the cowboys what they were in for. If they caught the Red “on a rise,” all the rivers north were apt to be “up and swimming” too. The Washita and the North Canadian ran just as fast, deadly, and cold.

The Red begins with intermittent creeks and flash-flood draws near Tucumcari, New Mexico, but it becomes a flowing river just south of Amarillo in the Panhandle’s geological showcase of soil erosion, Palo Duro Canyon. Between the 101st and 100th meridians, the river’s forks and tributaries continue to cut through the buttes and mesas of a crumbling, calcareous clay formation called the Permian Redbeds. Farther east, Oklahoma creeks deepen the water’s rusty shade with iron and other minerals washed down from the Wichita Mountains. From streams, gulleys, and bar ditches above Lake Texoma, about 20 million tons of dirt erode toward the Red River every year. Below the dam, loam banks slough off and hit the water with a startling galoomp. The loose banks stir more mud into the mixture all the way to Arkansas, where the river makes its big south bend, and on through Louisiana, where it eventually joins the Mississippi River. The Red can’t help its color.

In the North Texas counties where I grew up, soil conservationists and highway engineers use junk cars to keep good dirt and bridges out of the Red River. Against the caving banks, the Hudsons, Studebakers, and Olds 98’s are planted side by side with the heavy engines down, windows broken out, connected by strands of oilfield cable—a nostalgic kind of boondock pop art, I always thought.

The river’s charm and value lie in the bottomland. Teenagers make sunning beaches of sandbars that can be as white and soft as any dunes on Padre Island. When I was in college, we sang, boozed, and kissed around blazing campfires on the Red. River-bottom parties were high points of the year.

Other nights we crossed the bridges and descended on latter-day juke joints that served up fried catfish, hush puppies, beer, mountain oysters, and yowling country and western, all under the same roof. A vestige of days when the majority of North Texans voted to keep their counties dry and sober, those service establishments are strung all along the southern Oklahoma border. Boundary streams are more than bodies of water; depending on the direction of travel, they stir feelings of safety and homecoming, peril and adventure. And in Oklahoma, that strangely foreign land, anything could happen. You might fall in love. You might get knifed.

Get Along, Little Dogies

Between 1867 and 1895, nearly 10 million cattle and a million horses moved up the trails that crossed the Red. Unlike the movie cowboys, the men who drove the Longhorns feared stampedes far less than they feared rivers. Stampedes frayed their nerves and kept them up all night; river crossings killed them.

The cowboys’ tales are as hair-raising today as they were when told around the campfire. Drovers used drowned horses for pontoons to float wagons across. One drover risked his life to rescue a mule that was desperately treading water because a cracked willow limb had snagged gear tied around its neck. Another time, in a flooding Red, two drovers somehow unsaddled a panicked horse that refused to swim. Tied to the saddle was a cowboy’s watch and his $300 stash.

The Chisholm Trail, named after a half-breed Cherokee, Jesse Chisholm, crossed the Red near the mouth of Salt Creek, a tributary in Montague County. The crossing at Red River Station was marked by a store-saloon and a raft ferry. Because of the exigencies of grazing and market, the Longhorns usually came up the trail during the spring storm season. One cowboy recalled an 1871 flood that had thirty outfits and 60,000 head backed up forty miles south of the Red. Another vividly remembered the river’s power: “We had some exciting times getting our herd across Red River, which was on a big rise, and nearly a mile wide, with all kinds of large trees floating down on big foam-capped waves that looked larger than a wagon sheet, but we had to put our herd over to the other side. . . . Three herds crossed the river that day and one man was drowned, besides several cattle.”

Even today the Chisholm Trail is at the heart of Red River folklore. To find the crossing, you take FM 103 north from Nocona, wind off westward on Montague County roads (some unpaved), and finally ask a farmer if this is the right plowed field. Next one over, he replies. Landscaped with yucca and wildflowers and protected by a chain-link fence, the state’s monument to Red River Station explains that an abrupt bend in the river checked the flow and created the fording spot; at the peak of traffic on the Chisholm Trail, some days the cattle were so crowded that cowboys walked on their backs. A few yards away, almost hidden by brush, a bullet-dented metal sign denotes the Scenic Chisholm Trail Walking Tour. The bank slopes down about a hundred yards, but you wouldn’t want to picnic on it. The shallows look creamy and stagnant. The air sings with mosquitoes and gnats.

Spanish Fort, the next settlement downriver, is about five miles away. On a punitive expedition against all Plains Indians in 1759, Spanish soldiers attacked a large settlement of Comanches there and got themselves thrashed. The Spaniards said the Indians had constructed moats and swore the stockade flew a French flag. Today fewer than a hundred people live in the historic town. The onetime grocery store and post office has a new name painted across the front: “Spanish Fort Coon Hunters Association.” Inside, an old-timer named Virgil Hutson lives with his wife, Mary. He sells hunting clothes and dog collars and posts neighbors’ bulletins. “Wanted,” says one. “Broke mule-15 hands or taller.” The Hutsons do some truck farming. The fertility of the valley’s alluvial soil enables Mary to brag on a seven-acre plot that yields twenty bushels of tomatoes a day. But the river can also take the bounty away. Mary tells me she has seen it twelve feet deep behind the white house at the end of the road. The actual river bed, she goes on, is a mile and a half beyond.

The paved road runs out at Spanish Fort. On Texas highway maps the Red River Valley’s farm-to-market roads are often dead-end streets. The Mississippi’s southernmost major tributary, the Red River flows 1,200 miles from its headwaters on the dry plains of New Mexico to its mouth through reasonably populous country. But above Shreveport, Louisiana, no town or city is properly built upon it. Not one. The Red’s uncontrollability has created one of the longest corridors of rural lifestyle to be found in this country. If rivers can be invested with human traits, this one chortles at our expense.

Land for the Taking

The land grabs associated with the Red River were shameless from the start. When Thomas Jefferson purchased 800 million acres of wilderness from France for $15 million in 1803, Louisiana was loosely defined. Because the French explorer Sieur de La Salle had oversailed the mouth of the Mississippi 219 years earlier and camped for a few months near Matagorda Bay, Jefferson proposed the Rio Grande as the southern boundary. “Absurd reasoning,” replied a Spanish diplomat. The Red River became the Americans’ fallback position.

The wrangling over the Louisiana Purchase continued until 1819, when John Quincy Adams, as Secretary of State in the administration of James Monroe, negotiated the treaty with Spain. When a river becomes an international boundary, ordinarily the territorial claims meet at the midpoint of the stream. Ensuring the Americans’ navigation and water rights, Adams’ treaty defined the boundary as the Red’s south bank. In turn, the treaty had to be honored, if renegotiated, by revolutionary Mexico and then by the Republic of Texas.

The first Anglo-Americans were fugitives from justice; in 1811 about a dozen outlaws pitched camp in the woods near an ancient buffalo crossing of the Red. Pecan Point, as the fording spot came to be known, was a loose center of rural settlement, not a single community. The name “Pecan Point” referred to both sides of the river, but along with Jonesborough, a ferry crossing and village just upstream, it was the first permanent Anglo settlement in Texas—and the busy crossings of the Red River foretold the end of Hispanic dominion. The migratory trail channeled Sam Houston and Davy Crockett, with other pioneer Texans, to that narrow stretch of river valley. On the Oklahoma side, the U.S. government settled Indians whom it had forced off their homelands. Land north of the Red River was ceded to the Choctaws. A village called Shawneetown existed for a time. The Trail of Tears led to the Red’s north bank.

When Davy Crockett crossed the river two months before his death at the Alamo, he wrote home: “I expect to settle on Bodarka Choctaw Bayou of Red River that I have no doubt is the richest country in the world, good land and plenty of timber and the best springs and good mill streams, good range, clear water . . . game a plenty. . . . I am rejoiced at my fate.”

But the river itself raised a major objection to Crockett’s vision of Eden. For 165 miles in northern Louisiana, the Red was a growing logjam called the Great Raft. Though the river opened up in pools, the islands of dead trees created ten-foot dams of such compaction that shrubs and grass took root above the waterline. Geologists theorize that the backwash from a huge Mississippi River flood about A.D. 1200 may have first jammed the logs on the Red River. Whatever its origins, the Great Raft grew up to five miles a year. The spring floods brought durable cypress and cedar trees, which accumulated faster at one end than they rotted at the other, and the obstructed river spread laterally into lakes and bayous. The creator of Caddo Lake was probably the Great Raft—not the earthquake of popular legend. The Great Raft not only closed the Red to navigation, but it also disqualified adjoining terrain from cotton plantation or much permanent settlement. United States Army engineers said that nothing could be done.

To the rescue steamed Henry Shreve in 1833. Piloting ships called the Heliopolis, the Archimedes, and the Eradicator, Captain Shreve essentially used them as battering rams. Hindered by sick crews, mosquitoes, and unreliable federal funding, he would back off and whack forward again, jars to neck vertebrae notwithstanding. It took him five years to clear the Great Raft; today the city of Shreveport proudly bears his name. Swamps drained and the prairies were restored. But even south of Shreveport, the Red was never navigable for more than half the year. Upstream, one prospective navigator counted 2,100 snags and 54 drift piles in a 222-mile stretch. Shreve died in 1851. The reassembled raft closed the river that year for thirteen miles. It took Alfred Nobel’s invention of dynamite, which facilitated underwater demolition, to free the natural flow.

Civilizing the upper Red posed an entirely different set of problems. The government could only theorize about its source, for the river cut through plains controlled by warlike Indians. In 1852 an Army captain named Randolph Marcy set out to find the Red’s headwaters. In the granite Wichita Mountains, fifty miles north of the Red River, Wichitas told Marcy that all tribes feared the ride that he proposed. Westward the Red was a stream of foul-tasting water that no one could drink. Marcy calculated that the surface gypsum belt that dosed area rivers with purgative salts was 50 to 100 miles wide and 350 miles long. The soldiers and animals suffered 104-degree heat and horseflies that Marcy claimed were as big as hummingbirds. During that summer, the column was reported massacred by Comanches. The War Department informed Marcy’s family, and a minister preached his funeral sermon.

Not yet informed of their demise, the explorers ventured up the Red’s North Fork. Marcy wrote that Comanches and Kiowas favored that stream, which crosses southwest Oklahoma and heads into the eastern Texas Panhandle, because of its rich prairies and abundant cottonwoods. When snow buried the grass, the Indians fed the trees’ sweet bark to their horses. But Marcy correctly read the North Fork as a tributary. Returning to the parent stream, the column resumed its westward march along the Prairie Dog Town Fork. Four months after receiving his orders, Marcy found headwater springs, if not the true source. For the first time, the water was clear and sweet. Above the cottonwoods were the magnificent multicolored cliffs we know as Palo Duro Canyon.

Texans were not immune to Red River greed. Contradicting Marcy’s definition of the headwater stream, in 1860 the state legislature claimed the North Fork as the boundary. Once the Civil War reestablished federal authority, the United States sued Texas for seizing a large chunk of southwestern Oklahoma. Reminding all parties of the 1819 treaty and Marcy’s authoritative pronouncement, in 1896 the Supreme Court defined the Texas-Oklahoma political boundary as the south banks of the Red River and its southern Prairie Dog Town Fork. But private property lines were a different matter, and the river never ceased revising its banks. The legal matter came to a head with the discovery of the Burkburnett oil field. Every inch of the river bottom was suddenly desired for its mineral rights.

In a Supreme Court case of 1923, Oklahoma sued Texas over bottomland in Wichita County. The federal government, which held the median riverbed in trust for Indian tribes, joined the Oklahoma side of the fray. Texas won that bout. Relying on scientists and surveyors who had tromped up and down the bottom, the court decision swung on the ways the river changes its course: If the river moves its banks by gradual and natural means of erosion or accretion—silting—all parties have to live with the consequences. But if the cause is avulsion, as a result of man-made interference or calamities such as a hundred-year flood, Oklahomans can legally redefine the south bank. The court accepted the scientists’ suggestion of the boundary as the south cut bank: “the more or less pronounced bank or declivity which borders the sand bank of the river and more or less limits the growth of vegetation toward the river.”

More or less. If only John Quincy Adams had known, while he was negotiating with Spain, that empty Texas would someday be part of the union, oh, the headaches that could have been spared.

The View From This Side

Claude Zachry’s picture window and patio overlook the bluffs of the Red River in Clay County, forty miles east of Wichita Falls. From his bermuda-grass back yard, the red clay drops off 150 feet. Zachry’s land value is bolstered by orderly pecan orchards spread across fields of maroon dirt, which he keeps planted in wheat and rye. About a mile away the sand flats and cocoa-colored river make a hairpin curve back toward the house and then disappear among the trees, seeking the mouth of the Little Wichita. Morning sun was burning through the night’s rain clouds.

Tall and long-legged, Zachry has lived on the ranch since 1929. While talking with him, I kept thinking of the old-timers in Larry McMurtry’s early novels.

“When the river floods, how fast does it rise?” I asked him.

“Depends on how much water there is down below,” he said. “If they’ve had rain downstream, that holds the head rise up. But it’s not always gradual. Flood of ’35, I saw horses and cattle and logs all come down together. Parts of houses with chickens still sitting on the roof.” He rose from his easy chair and stared at the bottom. “I drowned a horse in that flood. I was trying to get to some stranded cows and didn’t know how bad it was. I swam him back toward the bluff and climbed up in tree branches and hung on to him, trying to hold his head up. But it was too much for him. When we got to shore, he just gave out and died.”

Ranching the bottomland is not the same as running a place up on the plains. On grassland wooded with mesquite, cattlemen thank their stars for knee-high clumps of little bluestem. Down among the pecans, big bluestem rustles chest-high in the breeze. But while plains ranchers can leave tractors in a hay field, if there’s a chance of rain, Zachry moves his machinery to high ground for fear of losing it. Because the last big flood in 1983 deposited so much sand, he needs a four-wheel-drive pickup in the bottom pastures.

In recent years Zachry and other Texas ranchers on the Red River have been sued for prime land by Oklahoma neighbors. “Now, I know there’s nice folks in Oklahoma,” he told me. “But it’s different over there. When people first settled this country, nobody but outlaws would live across the river, because there were so many Indians and so few sheriffs. People say, ‘Well, all those bad sorts have been killed off.’ I say, ‘Yeah, but now you got the ones that killed them.’ ”

The latest Red River land dispute began in 1975 when a crew-cut Oklahoma rancher named Buck James sued Texans in Clay County for nine hundred acres. Represented by a former Oklahoma attorney general, Charles Nesbitt, James claimed that neighbors in Texas had squatted on his family’s bottomland since 1930. A federal district judge in Oklahoma awarded the acreage to James in 1981. Contradicting testimony in the Burkburnett oil-field case, the judge ruled that a 1908 flood met the legal definitions of natural calamity and that construction of the Texas Highway 79 bridge between Wichita Falls and Waurika had unnaturally changed the river’s course. So avulsion, not accretion or erosion, had repositioned the south cut bank.

This stretch of river recently has tended to shift its streambed northward, which accrues acreage for the Texans. But since the 1981 ruling, Texas landowners as far downriver as Denison have been sued for bottom pastures and even sandbars, which are quarried for gravel. Complaining that the burden of proof lies with them, the Texans are bitter. They say they are at the mercy of contingency lawyers who solicit clients along the river and file suit in Oklahoma for a percentage of whatever they can get. In Austin those suits have raised concern over the local taxing authority and enforcement of Texas hunting and fishing laws. The federal Bureau of Land Management has been trying to mediate an agreement among Texas, Oklahoma, and the Indian tribes. But as long as ambiguities like avulsion and accretion determine case law, a permanent political boundary will not halt contention over private property lines.

Zachry descended a steep graded road and cut through the plowed fields of his pecan orchard. As we left the pickup, he glanced at my feet to see if I was properly shod. The grass was wet, and snakes were out.

“This place can really grow the cottonwoods,” I said.

Zachry followed my upward gaze with less rapture. “Yeah. If there was any market for ’em, we’d sure be set.”

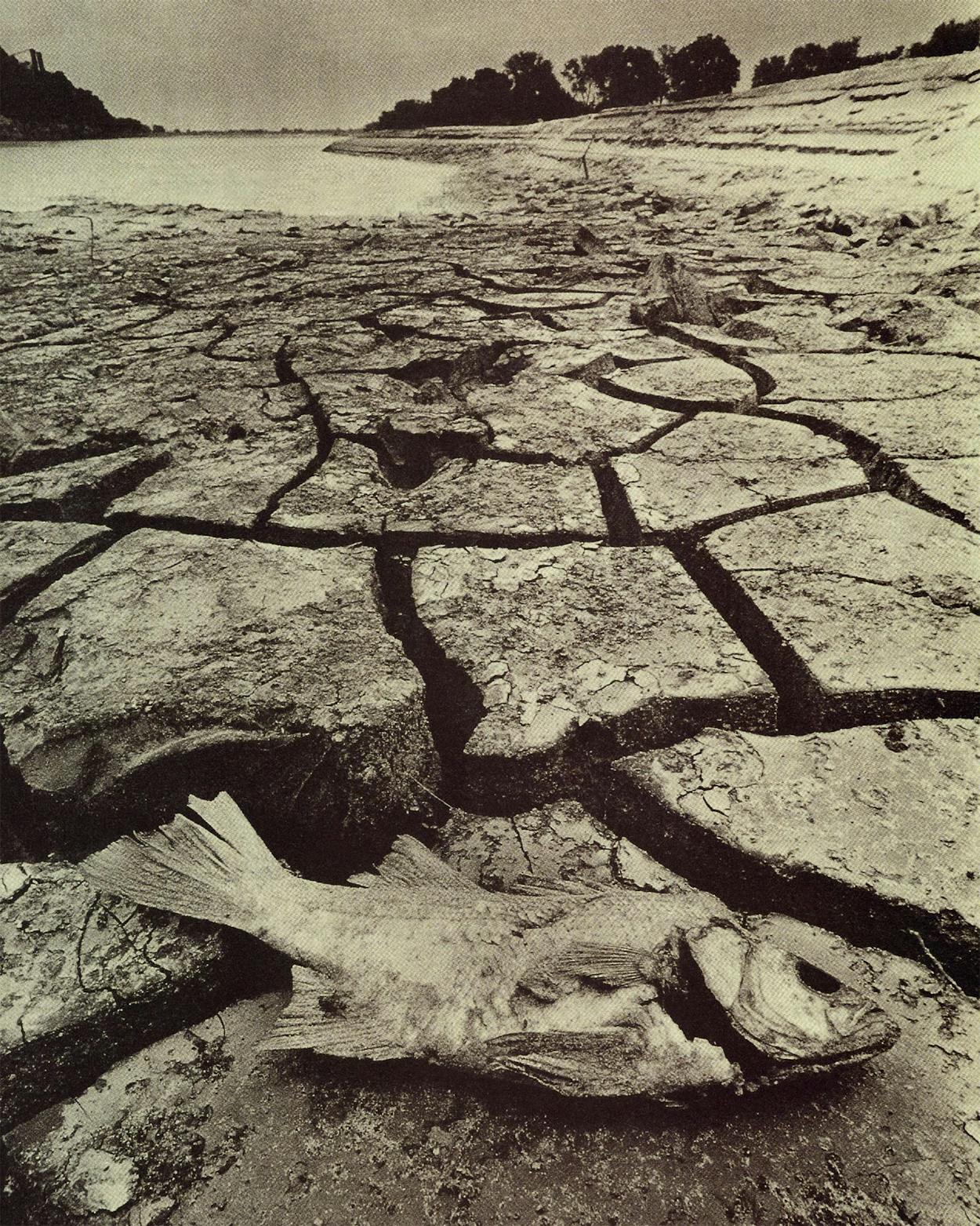

The red ground underfoot was broken up in triangles and trapezoids of half-inch crust. Short grass grew beyond the point where the ground looked solid. Along the bank the cracks in the soil were wider, predicting the next collapse. Served by crude gulleys and festooned with dead or dying shrubs and grass, the wet sandbars and silent river offered a sullen contrast to all this luxuriant green.

“You are standing on Red River’s south cut bank,” said Zachry.

“It just breaks off in the river, doesn’t it?”

“Farmers lost quarter-acres of cotton, in the old days.”

Quicksand, which pervades the Red’s legends, is created by upward-flowing groundwater that holds sand particles in suspension. But if you look for the cinematic gloop that has the consistency of Malt-O-Meal and slowly sucks you down to the chest and then to the chin, you won’t find it. In dry seasons the bed is laced with wind-arranged sand and alkaline grit. Near the dividing and intertwining streamlets, which may run no more than shin-deep, the ground looks damp but easily supports the weight of a horse. The mud makes squelching sounds under its hooves. The horse takes another step on ground that looks identical—and the bottom falls out. Plunging and pitching, it strikes for anything solid. If it topples, a rider can be crushed and buried.

“Some horses have a light step and a sense of just where they can go,” said Zachry. “We called them river horses and needed them, because we were always digging out bogged cows. If they got even twelve inches of a leg caught, it would hold them till they died.”

He moved the truck and showed me a spot with a higher cut bank. Pointing at willows and salt cedar, he said the changing river had given that acreage to Oklahoma. “It used to be yours?” I asked.

“Oh, yeah. I’ve ridden those woods a thousand times.”

He stared at the sandbars and reminisced: “In fact, when I was a young man, we used to cross it here every Saturday night. The closest dances were over in Ryan. When the moon’s up on it, I never have seen it when it didn’t look half a mile wide.”

The River Tamer

The prettiest stretch of river valley lies due north of Dallas. Here the longest of the Oklahoma tributaries, the Washita, angles down through the eastern Cross Timbers. Fringing the rich tail-grass prairie, the narrow strip of oak and elm forest attracted settlers because it supplied fuel and lumber. Preston Road in Dallas was once the link to the Butterfield stagecoach line’s Red River crossing. But the Red’s history is least recognizable along this stretch of river. If downstream towns and thousands of acres of farmland were ever to be spared its floods, a dam had to stop the Washita too. Planning of the dam at Denison, ten miles below the Washita’s mouth, officially began in Congress in 1927.

Since Lake Texoma would back far up the tributary and remove 200,000 acres from cultivation and property tax rolls, an Oklahoma governor called “Alfalfa Bill” Murray denounced it as “the biggest folly ever proposed.” During the dam’s construction, Oklahoma twice sought workstop injunctions from the U.S. Supreme Court. But no Oklahoman wielded as much power in Washington as Texas congressman Sam Rayburn from downstream Bonham. Because it was a domestic priority of the Speaker of the House, the Red River dam was completed in 1944—one of the few public works projects allowed to continue during World War II.

With 585 miles of shoreline, Lake Texoma is now the country’s tenth-largest reservoir. The four-state apportionment of water rights irrigates some farms, and two generators in the dam provide backup electricity for towns and rural cooperatives in Texas and Oklahoma. But the lake’s primary purpose is flood control. When a flood crests near Wichita Falls, it takes about three days to reach the Denison dam. Gauges up and down the river beam signals to satellites, which relay them to computers at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers office in Tulsa. That data determines the release of water through the dam. A June flood in 1957 cleared the dam by three feet and made a beautiful and frightening waterfall of the spillway—the only time the system failed. Ordinarily, the depth of the lake turns the river’s homely brown a pretty jade green.

More than eight million tourists visit Lake Texoma every year. Convenient to Dallas–Fort Worth and Oklahoma City, docks of yachts and sailboats and hillsides of condominiums have begun to appear. Urbanity encroaches, but the submerged cut bank and its foibles won’t go away. Anglers can fish with special Texoma permits or take their chances with different game wardens and laws on either side of an imaginary Texas-Oklahoma boundary in the middle of the lake. Authorities briefly tried to mark the state line with a thirty-mile string of floats, but they proved impractical and were soon removed.

Below the even grass lawn of the earthwork dam, the Red reemerges from twenty-foot tubes. Frothing and slowing the water is a grid of concrete bulwarks patterned like a waffle iron. A reinforced building at the foot of the dam contains the generators. Inside this structure I met Guy Beasley, then an area engineer at Lake Texoma. A rawboned man of ruddy complexion, he said he had been a small-college football coach, a petroleum engineer, a civil engineer, and a missile engineer; he applied for this job so he could move back home to Madill, an attractively wooded little town north of Texoma. Since the computers in Tulsa effectively regulate the flow, most of Beasley’s work concerns management of the parks and campsites.

Coming into the building, I had passed a photo lineup of military men who have ranked in Denison Dam’s chain of command. “So where’s the Army?” I asked him. “Do you ever see uniforms?”

“Hardly a one,” he said. “The Corps of Engineers is mostly civil service.”

The outdoorsman’s workplace was a small windowless office with dim unnatural light. Glad to take me for a drive, Beasley directed me to an elevator. We came out in a humming ground-floor room that houses the generators; they looked like upside-down tops. He pointed at the concrete floor between them. “Since Texas and Oklahoma share the electricity, we figure that the state line goes right through there,” he said.

Along the dam we poked through a field of little bluestem. A small bridge over a gulley marked an old driveway. Veiled by the prairie grass were the straight lines of razed buildings.

“This was a German prisoner-of-war camp,” he said, stopping the car. “There were two more over in Oklahoma, at Powell and Tishomingo. They were Panzer troops who had been captured in North Africa, and they finished the work on Lake Texoma. It was one of the largest clear-cutting projects in the history of the United States. They didn’t have chain saws then, so it had to be hard labor, but we never heard of anybody trying to escape. When I was a boy, a forty-five-piece orchestra of Germans played a concert at my grade school. They had one guard who wore a side arm. They must have played Wagner or something like that. Prettiest music I’d ever heard.”

Living on the Edge

Downstream, near Bonham, a friend and I watched a bored Oklahoma kid pass the time peeling out again and again on the Texas Highway 78 bridge. Working our way east, we crossed into Oklahoma wherever we could, but pavement was scarce along the river, and the farmhouses looked like Woody Guthrie’s hard travelers had just gone down the road feeling bad.

We circled past a drive-in with a terse and directly worded sign—“Bob’s Beer”—and left the car on the lot of a large corrugated-metal barn. “Red River Junction” was painted across the front. The river there was a quarter of a mile wide. It rose against the bridge abutments and swelled around them with a sound of rapids that you wouldn’t want to swim. Brush and foam gyrated in the whirlpools.

Fifteen miles into Oklahoma we came to Idabel. On a side street we considered a long, narrow building, unidentified except for a small solitary window filled with crumpled tinfoil and blue neon letters—“Coors.” The place was run by Rosie. She had a black beehive hairdo and an ornate rose tattooed on her chest. On her forearm was a cruder piece of work—“Mean Bitch.” The menu options were nothing but beer, cans or throwaway bottles, $1. On the stool next to me was a woman, about 23, named Jan. She wore a white long-sleeved shirt and blue jeans tucked into fringed moccasin boots. After a while we went out back for a breath of fresh air. It had rained that week, and the alley was filled with deep auburn puddles.

“Have you ever gone anywhere?” I asked. “Traveled?”

She stiffened and shrugged. “I been to Texas.”

At that moment a big gray-haired farmer walked out the back door and took long strides across the mud puddles. He was Jan’s father. He paused on the heel of one brogan and offered his opinion of me without turning his head: “Best get home, girl.”

Back on the Texas side, my friend and I passed through lush meadows and hardwood forest. The names of the Texas villages—Ivanhoe, Tulip, Telephone, Monkstown, Direct, and Chicota—reinforce the appearance of rustic contentment and prosperity. Though the river can seldom be seen, travelers sense its nearness in long spaces that open up in the horizon of blue-green foliage.

On the shoulder of U.S. Highway 271, which connects Paris with Hugo, Oklahoma, my friend and I hammed and photographed each other beside the upright granite map of Texas that marks the state line. The boundary markers are strapping and friendly things; you want to stand up against the Sabine and throw an arm around the Panhandle.

The Red River is no River Jordan, and even with the moon shining on the sandbars, it’s not half as pretty as the Seine. It’s just a muddy border stream. But coming southward, I always breathe easier when I hear the clicks under my tires of the narrow two-lane bridge. I know I’m back where I belong.

- More About:

- Water

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Panhandle