A few weeks ago, when temperatures hovered in the mid-60s across much of Texas, Wayne White stepped outside and felt the sting of minus 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

That ranked as somewhat balmy, in relative terms, for White, who is wrapping up his third winter as site manager of the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica. There, he’s responsible for the safety of a team of 42 technicians, scientists, and support staff. On an especially frigid day, as he tugged a jacket tight around his face and crunched across a sheet of white ice that extends for a thousand miles in every direction, he heard a whooshing sound as he exhaled.

“When you breathe out at minus 80 degrees, there’s a strange noise,” he says during an interview conducted via satellite phone from the station. “That’s your vapor freezing as it hurtles out.”

White, who lives in Rockport when he’s not manning research stations around the globe, tells me conditions look perfect for his daily walk later in the afternoon, after he finishes his weekly status call with the National Science Foundation (NSF). At the South Pole, he’s responsible for the safety of the crew, as well as maintaining the station itself and all NSF facilities. He makes rounds daily, checks on facilities and the crew members’ well-being, and generally makes sure things are running smoothly. “There’s nice sun and not much wind today,” he says. “Nothing but ice, nothing alive.”

White, 64, has grown accustomed to the extreme climate of his temporary home, where the sun finally came up in September after nearly six months of complete darkness. While working ten- to twelve-month stints at the South Pole, he endures wind chills of minus 134 degrees, subsists mainly on frozen foods, and sleeps in what he describes as a jail cell–size cabin.

“When you get to minus 80s or 90s … it’s amazing how fast you start to freeze and it starts to hurt,” he says. “In just minutes you’d lose your face, your ears, your feet.”

From April to September, the station plunges into total darkness, and temperatures regularly hover around minus 100 degrees Fahrenheit. That doesn’t stop White, who has been at the station since January, from getting out for his daily walk or run, always solo. In almost three years on the job, he’s never passed a day without venturing outside. White records every session, and so far has logged more than four thousand miles on the ice. “I go in any kind of weather,” he says. “It doesn’t matter how bad it is.”

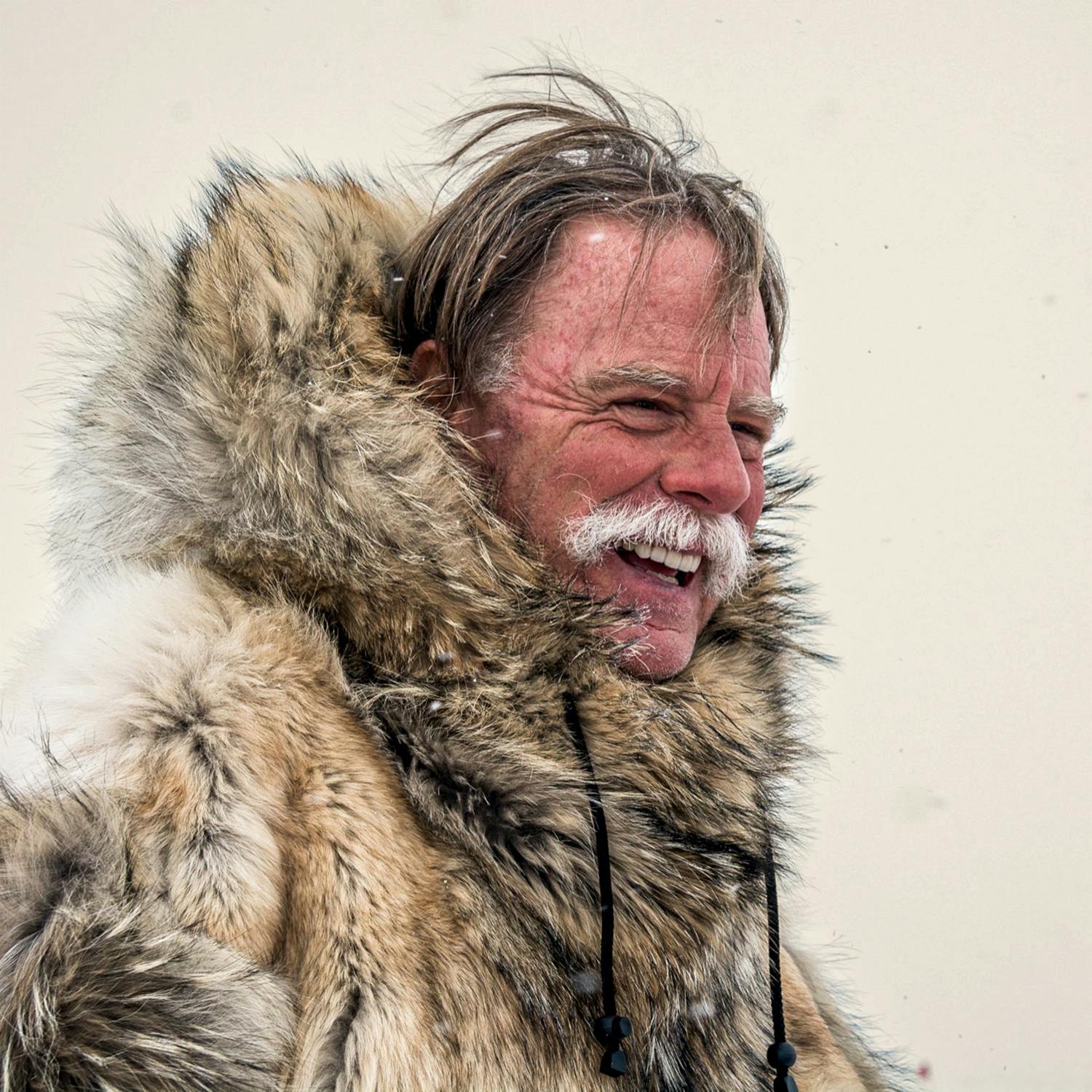

Before he heads out the door, he signs a dry-erase board (which features the handy notation “If no return, look for frozen pile when sun returns in September”) to let his crew know he’s out exercising. When getting dressed to go out, he chooses from utilitarian gear used by the military in extreme cold, a heavy canvas anorak like the one explorer Roald Amundsen wore when he was at the South Pole in 1911, or, on the most miserable days, an Inuit jacket made of Siberian wolf fur. He knows how to read the wind, stars, and snow to find his way back, even in utter darkness or whiteout conditions. “One of the worst things you face here is the wind,” White says. “The wind works its way in, and you get frostbite on your nose and face.”

The station where White works sits on two miles of constantly moving ice near the geographic South Pole. Several other buildings are scattered within a kilometer. Sure, the crew endures complete darkness for months on end and no one can fly in or out between February and November, but aside from inconveniences such as the short daily windows of reliable internet connectivity, an absence of TV and streaming video, and an inability to vote in the 2020 election because there is no mail service (some crew can vote by fax, depending on rules of their home state), it’s really not so bad, White says: “I have learned to love this … I love the harshness of this place and its history.”

A hint of light first appears to the station’s inhabitants near the end of August, a pale smudge along the horizon. A few weeks later, the station hosts its annual Sunrise Dinner. At this year’s event, White congratulated his team on making it through the winter at the remote station, an accomplishment only about 1,600 people can claim. Every success is the crew’s, he says; every failure is his own. Then he touched on the much different world the crew would find when they fly out in November. “We’re going home to a new world, a world that isn’t quite the world that we left,” he told them.

Nobody at the station wears a mask—with no outsiders since February, there has been no need—and the crew doesn’t social distance. “Some people will say to me, ‘You’re lucky to be down there during this,’” White says. “But I say it’s hellish. We can’t do anything for people back home. We’ve had deaths, unforeseen divorces, hurricanes, and fires back home, and we can’t do a goddamn thing to help … I’d much rather be home than dealing with it here.”

White, who has served as station manager at nearly twenty other posts around the world, from Ascension Island in the South Atlantic to Wake Island in the western Pacific, is a member of the prestigious Explorers Club, alongside astronauts and deep-sea divers. He will return to Rockport in mid-November. When he does, he’ll become the first person to serve as winter manager of the station three times, marking a collective two and a half years at the South Pole. In the 64 years the United States has had a presence at the South Pole, only two other winter managers have lasted two seasons; White is the only one to make back-to-back winters. The South Pole time, he says, is just “a chapter in a pretty goddamn adventurous life.”

White was born in Maryland and grew up in Iowa. He earned a degree in geography from California State University, then got a master’s in public health from Tulane University before landing a series of contracts providing operation management and support for research stations around the world. He’s always loved adventure and history, and the work takes him to some of the most extreme places on the planet.

But three winters at the South Pole is enough, he says. It’s a lonely existence, and White misses his wife of 21 years, Melissa, who has traveled all over the world with him but never to the South Pole. He also misses their cats, all 18 of them, which were rescued from hard-luck situations. White passes the time by working on his two books in progress, one about the 21 years he’s spent working around the globe and another about the South Pole experience, focusing on the psychological impact of living in so much cold and darkness.

He compares life at the station to a space mission. “Imagine you’re in an alien world, with temperatures colder than minus 100, and you block the windows with cardboard to not let light out to affect the telescopes.” The solitude breeds close connection with his fellow adventurers, however. “I’m used to these types of environments, but the intensity of a South Pole winter and the closeness of South Pole crew—there’s nothing like it on the planet,” White says.

Nancy McGee, a filmmaker and fellow Explorers Club member, compares White to the Antarctic adventurers Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton. “I have no doubt those iconic polar explorers would list Wayne White in their top five as an intrepid exploration and expedition leader,” she says.

For now, he’s anxious about flying home—a long journey that takes him to New Zealand, then on to the United States. Upon his arrival in Rockport, he plans to self-quarantine for two weeks. “Normally there would be an airport welcome home. This time I’ll take a taxi or rental car and go to my guest house and wave to my wife from the backyard,” he says. “She’s a teacher. The last thing I want to do is expose her and then those children [to COVID-19].”

After eating almost exclusively frozen food since February, White is hankering for some Mexican food and a nice fresh salad—and a trip to the grocery store. “You can’t imagine what an H-E-B seems like after being here for a year,” he laughs.

- More About:

- Rockport