This is the biggest sky you will ever see. Twenty minutes south of Amarillo, running down the backbone of the southern High Plains on Interstate 27, the land is so prodigiously, stupendously flat that at its margins, at the milky-blue line where sky meets earth, it doesn’t end as much as it seems to dissolve. It is so empty of the usual monuments of civilization that structures like grain elevators and cotton gins loom up from the green-brown farmland like medieval fortresses.

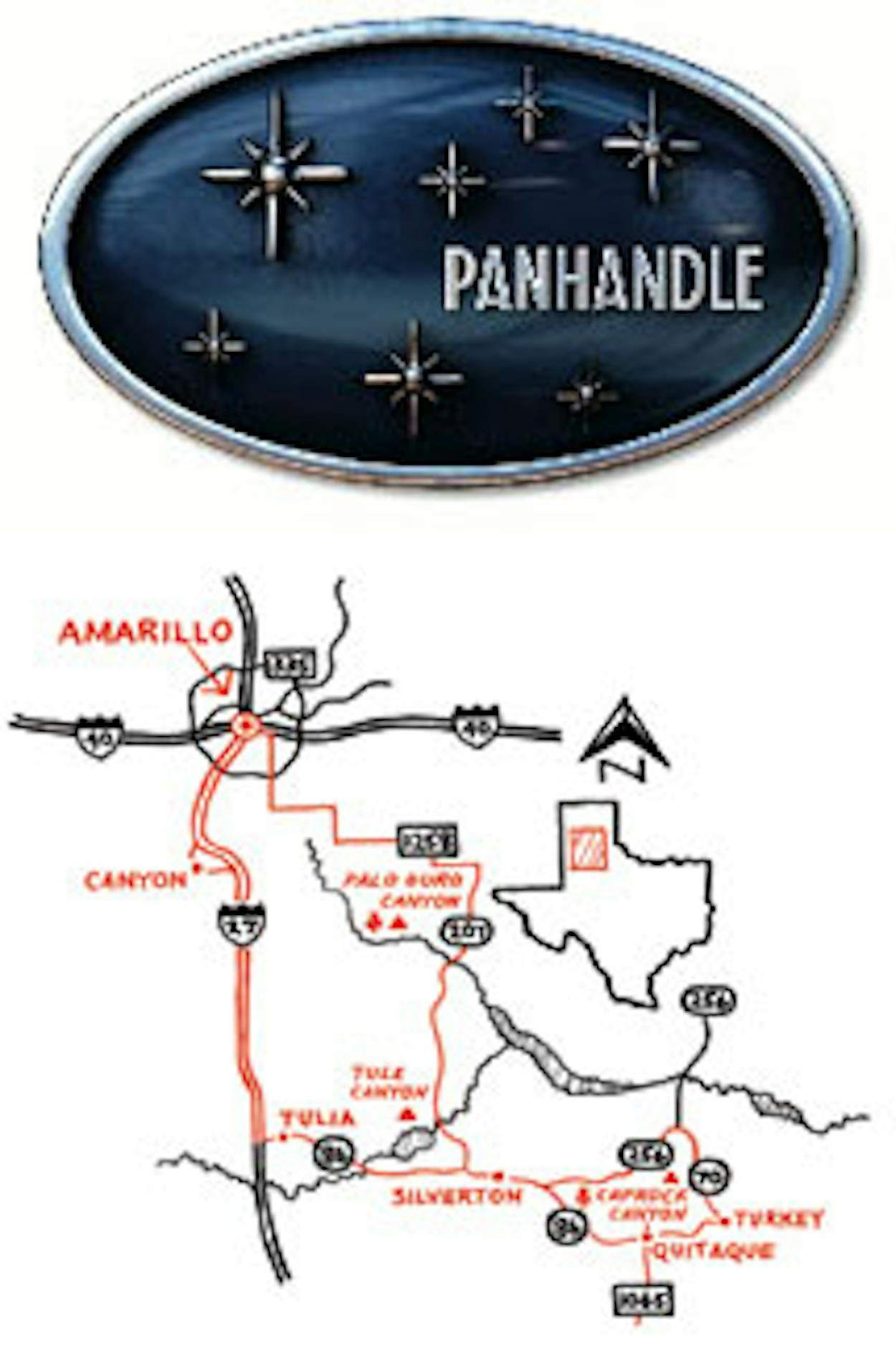

You are heading toward lovely, nearly vacant country that, if you pay close enough attention, will teach you a great deal about the High Plains, one of the most peculiar and physically stunning parts of the American West and the last major geographic part of continental America to be colonized. It was conquered and settled in the late 1800’s, in spite of a brutally inhospitable climate and a superabundance of hostile and highly motivated Comanches. I have chosen I-27 as the starting point because it offers a breathtaking and instructive view of the agricultural plains. Not only that, but it skirts the east side of Canyon, just south of Amarillo, where you can start your day at the superb Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum, a repository of easy-to-absorb information on the history, geology, and economy of the exotic world you are going to see. If the wind is right, Canyon is also where you will get your first whiff of the giant cattle feedlots of the Panhandle. Locals say it is the smell of money, and they are right, for whatever comfort that gives them.

On the way to Tulia, 32 miles south of Canyon, you get your first visual lesson in why this place is different: There are very few trees. That is because there is virtually no water; the average annual rainfall is only 21.5 inches. Indeed, there are very few trees on the entire 500-by-1,800-mile expanse of the Great Plains. When the first pioneers emerged from the dense, primeval forest that extended from the East Coast uninterrupted to a line running, roughly, directly north from Houston, they were horrified at the stark, unsheltered emptiness before them. It was nearly impossible for them to imagine farming without water or wood in a climate characterized by scorching summer heat, lethal winter blizzards, tornadoes, dust storms, frequent droughts, and hail the size of baseballs. They had a name for this vast expanse of buffalo-dotted grassland: the Great American Desert.

Considering all that, you may find yourself wondering why the Panhandle Plains are full of prosperous, horizon-spanning farms these days. Lesson two: The settlers solved the water problem. In the 1880’s, windmills allowed them to pump water from wells in upland areas and thus move both their homes and their livestock away from the banks of the only two rivers in the Panhandle: the Canadian and the Red. Then, in the past century, they figured out how to drill down into an enormous, 156,000-acre underground body of water called the Ogallala Aquifer. The farms you see are intensively irrigated—so intensively that they are quickly sucking the aquifer dry.

As you head to Tulia, there are several things to take note of. Giant center-pivot irrigating machines, which stretch the length of football fields, are everywhere. They all use water from the Ogallala. Notice the playas, shallow, clay-bottomed lakes that form all over this country and provide water for livestock and habitat for wildlife. Along with the two rivers, they represent the only sources of surface water in the Panhandle. In winter they are full of ducks and other migrating birds. Notice too the ubiquitous steel-walled cotton gins.

At Tulia, turn eastward toward Oklahoma on Texas Highway 86 and prepare to discover that the High Plains are not, as many people believe, just one flat expanse of fertile dirt produced by the river-borne erosion of the Rockies. East of Tulia, the land begins to bulge and dip here and there, evidence of a much bigger change to come. After 24 miles, just beyond a dowdy little town called Silverton, everything changes. Between Silverton and Quitaque, you suddenly plunge downward off the plains through a deeply cut canyon land where almost every single aspect of the terrain changes. Open, treeless prairie gives way to reddish dirt covered with juniper, mesquite, yucca, and prickly pear cactus. Flat cotton and wheat fields yield to steep ravines, draws, jagged buttes, twisted lava columns called hoodoos, and mesas banded with bright colors.

It is an astonishing change, part of a 250-mile-long geological formation known as the Caprock that runs in a roughly north-south line through West Texas. Sometimes it appears as a long ridge, a 50-to-150-foot-high cliff of red and tan rock. Sometimes it appears as broken canyon lands. It separates the higher elevations of the southern High Plains from the uniformly lower elevations of the so-called Rolling Plains to the east. It’s also a sort of prosperity line, dividing the more affluent oil and agrarian uplands from the more hardscrabble lower plains; the Panhandle’s big cities, Amarillo and Lubbock, are west of the Caprock.

Quitaque is in cotton country, which you can’t help noticing because wisps of cotton line the roadsides. Sometimes it is so deep it looks like snow. The tiny, five-block-long town has a decent restaurant, the Sportsman (“Thirsty?” the sign reads. “We got all that stuff. Best deal in the country”), and a couple of antiques stores, and just east of town on Highway 86 is the marvelous Midway Drive-in Theater, now outfitted with big wooden benches. But Quitaque’s main attraction is Caprock Canyons State Park. One of the real gems of the American Southwest, it is well worth the three-mile detour north from Quitaque on Farm-to-Market Road 1065.

The 13,906-acre park runs along the rugged caprock escarpment and boasts some of the most spectacular scenery in Texas. The park roads wind through brilliantly colored, river-cut canyon land, bright red cliffs and mesas topped by the pale caprock. The bison here—56 of them—make up one of the most genetically pure herds remaining in North America. There are pronghorn antelope too. Best of all, there are thirty miles of excellent, groomed hiking trails. You can take short walks or long walks, over fairly flat terrain or up quite steep terrain.

Eleven miles down the road from Quitaque is Turkey, hometown of Texas Swing King Bob Wills. Here you’ll find a pink granite monument to Wills, a friendly little cafe called Lacy’s Too, the restored Gem Theatre, and not much else. From Turkey, head north on Texas Highway 70 through the broken canyon country of the Caprock; after a few miles you’ll come to an excellent scenic picnic area. Continue north for about ten more miles, then turn west on Texas Highway 256. Briefly retrace your route through Silverton, then turn right onto Texas Highway 207 for the spectacular finale of the day’s drive. Now you are heading due north, and soon you will start seeing the folds in the earth that tell you canyons are coming, and they are indeed: two yawning, miles-wide depressions with the same sort of tortured, colorful geology you saw at Caprock Canyons State Park.

The first is Tule Canyon. Here you can take a break and stretch your legs at lovely Lake Mackenzie, created by damming up Tule Creek to provide water for neighboring towns. The lake is also just east of the site where more than one thousand Indian horses were massacred by the Fourth U.S. Cavalry in 1874. The bone pile was a Panhandle landmark for years and gave rise to stories of phantom horses on moonlit nights. After emerging from Tule Canyon on 207, you find yourself again on the high, flat plains—ranching country now, scattered with mesquite—before dropping yet again into the steep, mountainous, brick-red country of Palo Duro Canyon, which in America is second in size only to the Grand Canyon. (For camping and hiking, you can access this canyon at Palo Duro Canyon State Park, a few miles east of Canyon.)

Now it is time to head home. Keep pushing north for ten more miles on 207, and you once again bob up onto the broad plains, now measled with oil wells. Turn left onto FM 1258 and follow it back into the Amarillo area, where you can pick up I-40 for the journey’s short last leg. Before you saddle in, you might want to reward yourself for your long, sedentary day of scenery-watching by stopping at another plains landmark: the Big Texan Steak Ranch, on the right side of the interstate. There you can order a fat, juicy T-bone and talk about the amazing things you saw in the little-known canyon lands of the High Plains.