This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

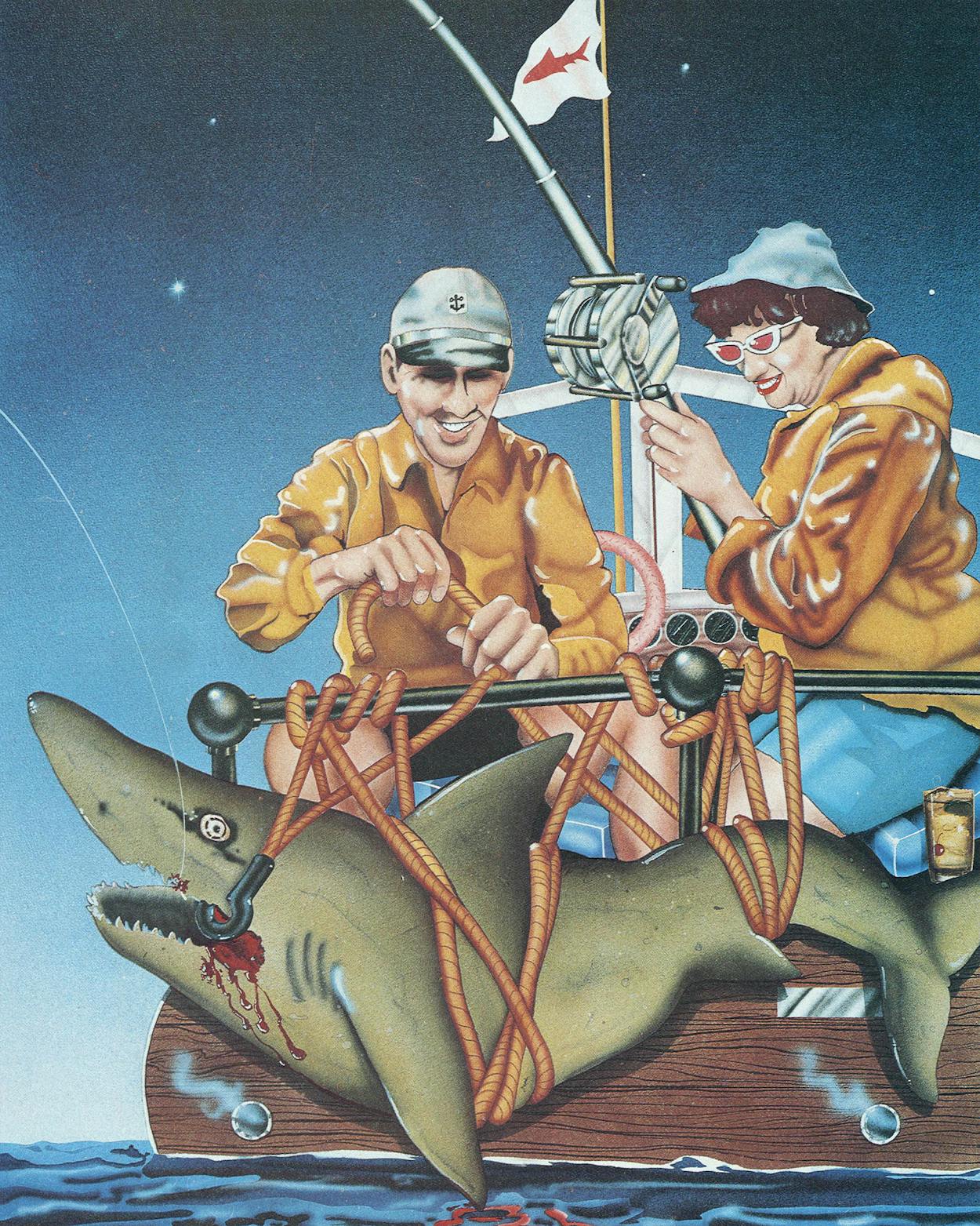

I’m a Corpus boy. Like most people who grow up on the coast I was in a position to develop an early attitude toward sharks. Sometimes I would come across the remains of one hoisted onto the “shark hanging post” at Bob Hail Pier, its mouth torn apart from two or three hours of fighting a hook, its body covered with gaff scars and encircled with ropes and chains and marked in chalk with its length, weight, and species.

Even as I watched it hang there like a punching bag, surrounded by its grinning captors, it was difficult for me to be sensitive to anything but the awesomeness of that creature. I did not ask myself, as I am prone to do now, what purpose was being served by the death of this shark. I just stared. Even in death the fish’s features seemed still attuned to blind menace, and like most observers I assumed that the shark had died by its own karma. It simply got what it deserved.

For a boy who wanted above all else to have a cunning, benevolent dolphin for a friend, who would leave the room when someone assaulted my ears with the word “porpoise,” who rode the Port Aransas ferry back and forth to watch those clever mammals cartwheeling in the ship channel, the shark was allowed only a grudging place in my personal ecology. In the underwater morality play that I imagined ran continuously in the murky bays and lagoons of Corpus Christi, the shark was the inevitable villain, a constant threat to the dolphins’ warm-blooded Never-Never Land.

Though they shared the same environment, though they shared very nearly the same bodies, the shark seemed to me a dolphin stripped of all resonance and humor, like a grandfather clock whose works had been removed but which still was diabolically able to tell time. I was stunned for days when I opened my new Time-Life book The Sea to find a picture of a shark tearing flesh from a dead dolphin. There had never been a plainer, eerier contrast: the dolphin’s permanent smile, subtly altered in death, made me think of the way Marlon Brando always looked just before he was about to cry. The shark, on the other hand, was a dead-ringer for Broderick Crawford, and there was a look of such profound and aggravating disinterest on its face that I was brought almost to tears. How could the Natural Order of Things take such sinister form?

For a long time the shark remained my counter-totem. As far as I was concerned the more death that could be wrought upon those creatures the better. Then one day I was on Padre Island gazing down at the body of a five- or six-foot shark that had obviously washed ashore long before I came across it. It was so bleached and bloated that, except for a persistently fierce-looking set of jaws, it might have been a tuna. A man in a polka-dot railroad cap walked up and automatically kicked the shark in the gills the way he might kick the tires on a used car. “That’s a shark, boy!” he pronounced. “I know,” I said, suddenly realizing that, though I did not yet love sharks, I could see when they were being ill-served. And it became evident, as the man pried open the fish’s mouth with a stick, that I must make some accommodation with those rows of teeth or be forever aligned with this bumpkin who was guffawing down the shark’s throat.

And there is of course much about sharks to be appreciated, much that is pesteringly beautiful, that cannot be sentimentalized. No other animal is so exactly what it appears to be. By human standards the shark is ludicrously primitive; but judged by its own needs, and by its own evolution toward meeting them, it is flawless. Nothing about the shark is peripheral: it exists to subsist, and is masterful at it.

The shark is unaware of and unreliant upon anything its senses do not interpret as food; so it does not attack out of nobility or nastiness or confusion or boredom. The shark’s only motive is ingestion: it abhors the vacuum that its own constant hunger maintains. Open the stomachs of enough sharks and you will find, besides maybe the chilling sight of human remains, everything from Vichy water to reindeer.

There are 34 species of sharks that inhabit Texas coastal waters. This is the conclusion of Dr. Donald Wohlschlag, who has been keeping count as he leafs through a zoological key to local marine life. Through his window I can see past the Port Aransas dunes out to the Gulf—a gray Gulf today, all its denizens securely tucked in. Wohlschlag is an ichthyologist and ecologist here at the University of Texas’ Institute of Marine Science, an idyllic laboratory/learning complex peopled mostly by tanned and bearded graduate students.

Wohlschlag himself is a rotund man with small eyes that crinkle up gleefully whenever the talk turns from fish to human folly. Sharks are really a little out of his line—he’s busy right now constructing a tank to monitor the metabolisms of pinfish and mullet—but he is ready to share both his literature and his opinions on the subject.

“Sharks are always super-nasty things in Grade B movies. We only listen to the propaganda. Did you know that at least half of the shark species aren’t bad to eat at all?”

Scanning Wohlschlag’s list, I’m pleasantly surprised to find that it includes the biggest of all fish, the whale shark, an animal that reaches a known length of 50 feet but which does not use its bulk to do damage to any form of life larger than plankton and small fish. In feeding, the animal creates a suction with its mouth and draws its food toward it, and fortunately for divers who have swum about whale sharks making a nuisance of themselves, its gullet is too small to accommodate them.

But there is another leviathan out there, this one so outrageously gruesome that it seems to have acquired its appearance not from nature but from the images of human nightmare. “The white, gliding ghostliness of repose in that creature,” was how Melville saw the great white shark, a fish that is not so much a fish as it is a twenty-foot cartilaginous void shoving itself through the ocean, ready to devour very nearly anything it encounters. It is a great white shark that lunges upward to imbibe the swimming woman on the cover of Peter Benchley’s novel Jaws, and though the proportions in that picture are exaggerated, it would be difficult to improve upon the natural grim reaper visage of the animal. Even the beast’s scientific name, Carcharodon carcharias, cannot be spoken without hearing the whisper of crunching bone. Great whites tend to be scarce, especially in this part of the world. The only confirmed sightings I’ve been able to unearth occurred near Port Aransas in 1950, but there have doubtless been a modest amount since then.

Other species are more common. Tiger sharks, hammerheads, bull sharks, makos, lemons all thrive along the coast, and all are more than capable of eating you or your lunch.

Most of the sharks people lose sleep over belong to one genus, Carcharias, all of whose members resemble the Revised Standard Version of shark that rests in the public’s imagination. An important exception is the hammerhead, from Sphyrna, a genus that includes a number of sharks with oddly proportioned heads. The hammerhead is the kind of fish you might expect to see surfacing from the ocean of another planet; Hieronymus Bosch could not have designed it better. While the heads of most sharks converge into respectable snouts, that of the hammerhead takes a wild, lyrical leap just a step further into the grotesque. Its head ends as a kind of crossbar extending laterally on either site much further than seems reasonable. This endows the hammerhead with a kind of fixed propeller which can give the fish either a whimsical or exceedingly grim look, depending on how near you are to the toothy trap door underneath it.

All sharks, though, share the same basic physical characteristics. For one thing, their skeletons are made not of bone but of cartilage, and the flesh that covers this frame is studded with thousands of toothlike projections that give sharkskin the texture of very coarse sandpaper.

Sharks perceive their world through smell and sight and sound, but exactly what it is that these senses serve is something we can’t know. Recent experiments have seemed to indicate that sharks do not experience what we know as “hunger.” Whatever causes their legendary voraciousness, it is not simply an empty gut. More likely the creature is impelled to eat by an agitation that invades the totality of its body: a shark is hunger.

The photograph album that Paul Dirk hands me across the dining room table has a flowery print cover, the kind of album usually filled with out-of-focus snapshots of the family at Disneyland. But I am in the house of a shark fisherman, and so I am not surprised when I come upon dozens of photographs of dead and disemboweled sharks, some of which have been enlarged and are hanging in frames on the wall above a row of trophies.

“I only make 8x10s of fish that are over eleven feet long,” Dirk explains.

Dirk is a big, courtly, deeply tanned man in his thirties who pours concrete for a living but whose joy in life is clearly the wresting of killer beasts out of the sea. Both of his fists put together would just about equal the size of the big Penn 16-aught reel that is fixed onto a 39-thread rod. He has almost $800 invested in this rig—even the hooks for shark fishing cost a dollar and a half apiece—and he has two back-up rigs in the garage.

Today is a miserable January day. Dirk is waiting for the middle of March, waiting for the water to reach 68 degrees so that the sand tigers and lemons, following the warmth, will move in closer to shore and start to feed near the oil rigs that are strung out in the Gulf, two to seven miles from shore. When the water reaches 72 degrees he knows it will begin to pull the hammers in, and at 75 degrees the tigers. He is erudite on these matters; his shelf-space that is not taken up by shark-fishing trophies is given over to a small library consisting exclusively of shark lore.

On the wall Dirk has a certificate of merit from the Corpus Christi Shark Association honoring him for the most sharks caught last year, but even for a pro it can be a tedious sport. It is not unusual for fishermen to camp out at the rig platforms for days at a time without a bite.

“You really got to put your hours in,” he warns.

People still fish for sharks from the Bob Hall and Horace Caldwell piers, but most of the action off Padre Island has moved out into the deeper water, out to the rigs that hover on the horizon like an oncoming armada. Before the fishing began in earnest out there, the 100 members of the Shark Association would catch as few as five or six sharks a season. From the rigs that record can easily be beaten in a month.

Dirk points out a photograph of the record tiger shark he fought for five-and-a-half hours. It was 12’1″ long, weighed 1160 pounds, and contained 66 tiger shark pups that it was about to let loose upon the sea. In the photograph the fish is slung up by its lower jaw on the shark hanging post. Dirk, his hair a little shorter, is standing beneath the dorsal fin as if it were an umbrella. Next to the great white, the tiger shark is the fiercest and is responsible for more human deaths than any other species. Dirk tells me that this particular shark tried to eat the rubber tires on the side of the platform as he hauled it up. Another tiger, a foot shorter than this one, attacked a hammerhead his wife Carolyn was hauling in and rendered it into the carnage shown in one of the 8x10s on the wall.

To catch a shark it is necessary to set the bait out about 500 yards from the platform, and since shark rigs are not exactly fly rods this must be done manually. On calm days Dirk and his colleagues board a rubber raft and paddle out with a big hunk of bonito or kingfish, set it in the water, and work their way back.

“Now when the water’s rough you can’t use a raft,” Dirk says modestly. “That’s when us hairy shark fishermen get out there.”

What he means is that they swim it out. Dirk’s own technique is to “hug the bait in close,” doing a modified side-stroke designed to keep the fish out of the water, where the smell and sight and texture of it would seep to the nearest shark. Five hundred yards from the nearest shelter, with eight or ten pounds of a shark’s favorite food cradled like a baby in his arms, Dirk becomes part of the public domain of carnivorous sea beasts. He leans back in his chair and relates a little too calmly several instances in which he has observed the famous fin zithering across the surface of the water.

“A lot of times you see them when they’re not even there.”

After a shark has been hooked, battled, hauled in, and allowed to expire, the rest is either afterglow or anticlimax, depending on who’s doing the fishing. The beast is weighed, measured, photographed, maybe its stomach opened, its jaws cut out, and then it is buried in the dunes. Occasionally an unconscionable restaurant will buy the carcass to turn it into “red snapper,” or the fisherman himself will make the effort to salvage the meat, but for the most part the shark dies not for what it yields but for what it does not. It dies for the sport it provides. Its own tenacity dooms it.

Paul Dirk opens the sliding door of his garage and the light pours in on the bags of concrete and bicycles and tools and all the standard accouterments of a suburban garage. But there, covering one wall, is something else. There must be twenty of them. Isolated from their owners, the jaws of these sharks do not seem particularly fierce. They crease in, some of them, at the center, so that those rows of teeth and cartilage seem almost comically puckered. I run my hand over the teeth of the big tiger. They are not especially sharp, not as sharp as I would have expected, but there are phalanxes of them, and the jaw that holds them seems triggered like a bear trap.

I stand there in a peculiar state of awe. There is something missing in my understanding of this graveyard.

“What do you feel about sharks?” I ask, “I mean what is your feeling about sharks?”

“Well,” Dirk says, indicating the set of jaws in which my hand is laid, “if you were gaffing that one there and you fell in with him you just know he’d chew you up in a second!”

On an August day in 1962, just about a year after a national study had concluded that the Texas coast was one of the few stretches of seashore free from fatal shark attacks, a 40-year-old Harlingen mechanic and German naval veteran named Hans Fix was surf fishing on Padre Island near Port Isabel. He had had some modest luck and had tied his stringer of fish to his belt so that they could remain in the water. The water came up to his waist, and, unless it was an exceptional day, it was fairly murky.

The shark hit him twice, both times on the right leg. Fix tried to beat it off with the only weapon at hand, his fishing rod. It might have done some good, because the shark did not attack again. His wife and two other fishermen, hearing his screams, entered the water and hauled him out. The lower part of his leg was badly mangled, and though he remained conscious and was able to describe the attack to his rescuers, he bled to death before he could be saved.

The attack on Fix is the only incontrovertible Texas shark fatality on record. There have certainly been others, but not many. It is probably true that the majority of shark attacks go unreported, since the whole point for the shark is the consumption of the evidence. But even taking that into account, Texas still remains a wonderful place not to be eaten by a shark.

Minor incidents, however, are common. One man recently stepped on a two-foot sandbar shark in the Packary Channel. The fish satisfied itself with a chomp at the offending foot and the man drove himself to the hospital. Coastal newspapers are full of the testimony of marooned fishermen who “fought off” or “swam with” or “saw the fins of” sharks on their way to shore. Surely most of these tales have grown in the telling, and surely many of the sharks who have kept a deathwatch over swimmers have turned out to be only inquisitive dolphins displaying their dorsal fins as they breached.

But it is still an undeniable and not entirely disagreeable fact that They Are Out There and that sooner or later a frequenter of salt water will see one.

When sharks attack human beings they do so out of the conviction that the potential victim is edible. The factors that contribute to this conclusion are unclear. There is hardly any doubt that it was Hans Fix’s stringer of bleeding fish that attracted the shark which killed him. A shark can sense gore across miles of water, and its prowess in rushing to its source is almost magical. In the same way it can read noise. A swimmer splashing on top of the water attracts a shark’s attention much more than the noiseless sauntering of a diver, and if a shark is attracted by noise, it is exalted when the noise becomes a thrashing panic.

Humankind is not the normal prey of sharks, but a shark is willing to waive that consideration if the signals it receives are familiar enough. Thus the first rule of shark avoidance: when in the water, do not behave like bait. Do not even associate with anything that can be construed as bait. If you are in the water and have caught or speared a fish, remove it or yourself at once. Avoid murky water. If a shark can’t see you, it’s likely to come in on instruments and its criteria for eating you will not be as strict.

And here’s some wonderful advice from someone who is sitting at a desk 200 miles inland: if you see a shark, stay calm. Look him in the eye. Chances are he’s not interested, but will readily become so once the scent of your terror wafts into his sinister nostrils and you begin to behave like a terrified and bite-sized kingfish. If the shark should attack, convince yourself that intelligence is on your side, that at last your college degree will be of some use. Then hit him on the nose, the famous One Vulnerable Spot, with the heaviest thing you can find, which will invariably be your hand, which will invariably end up in the shark’s mouth, stationed as it is underneath the sensitive nose. From there on out it’s all free-style.

Of course, the important thing to remember is that sharks rarely behave in any kind of predictable fashion. I have here on my desk an account of an attack on a boy in which the shark, a small great white, was so fixated in chewing on the poor kid’s leg that three rescuers could not loosen its grip and had to haul the boy and the shark both onto the shore where the victim was finally pried loose and saved. The shark was left to suffocate on the beach.

This is an unusual case, but it brings to mind an interesting sidelight. Most sharks, once they have settled on their prey, are not interested in anything else. This does not mitigate the heroism of the people who have come to the rescue of shark-attack victims but it does help to explain the fact that they are still alive. In 85 per cent of shark attacks in which the original victim is aided by another person the rescuer comes away unharmed.

All of this, I sincerely hope, is academic. The chances of being maimed or killed by a shark in Texas waters are staggeringly small. If sharks had wit, if their intelligence operated on the same frequency as ours, they might realize that they face, individually and collectively, a far greater risk of death at our hands than we do at their teeth.

A dolphin arcs across the logo of the bank building in which the Corpus Christi Shark Association is holding its biweekly off-season meeting. The dolphin has been idealized in the cause of gracefulness, just as the hammerhead shark on the CCSA’s own logo has been endowed with a spooky, tail-thrashing pose.

In the elevator riding up to the meeting room, I find myself surrounded by six people wearing shark’s-tooth necklaces. Paul Dirk is one of them, along with his wife and son. One necklace, swaying gently against the chest of its owner, consists of a single tooth that curves inward like a claw. For the duration of the ride it becomes an object of general admiration, and its owner certifies under questioning that it is indeed the tooth of a sand shark, Odontaspis taurus, a common enough species but one that is apparently not hooked with any regularity.

About 50 people have shown up by the time the meeting is to begin. They are a diverse group but there is some intangible link between them all, like the universal cartilage of their prey. There are old, weathered, astringent fishermen, young kids just out of high school with pointed cowboy hats and hair hanging lankly down to their shoulders, middle-aged men who look like pirates, women who are here obviously because of their husbands and women who are clearly here on their own. A man and woman arrive wearing identical maroon slacks, pink-checkered shirts, and white shoes and belts.

The conversation is about boats and weights and monofilament. I talk for a while with someone named Dan who does his fishing off a boat, farther into the gulf. He maintains that the sharks that wander near the rigs are sick, or lame, or lazy, or spawning. A boat gives him the opportunity to go after the lively ones, and after mako, the one shark that behaves like a big-game fish, leaping beautifully in its harassment, a fish for which Ernest Hemingway once held the Atlantic record.

Carolyn Dirk is not the kind of woman whose hobby you would expect to involve momentous battles with gargantuan sharks. She is in fact so demure and polite that when she says, in answer to a question, “I have an 8-7 tiger and an 8-2 hammer,” it seems that she is revealing the contents of a bridge hand rather than reciting the measurements of two monsters for whose death she has been the agent. Obvious questions are in order: for example, how did she get involved in this?

“Oh, my sister and I met some shark fishermen, and then I met Paul and we got married and I started fishing too. But I’d never fished, for anything! I sure enjoy it, though.

“You know, it may sound dumb, but if you’re going to go out there and fish that hard you want some glory for it, and the glory is getting up in front of the club and getting a trophy.”

The president of the club, who appears to be in his early twenties and has a faintly collegiate air, calls the meeting to order. He opens his briefcase and a bumper-sticker comes into view. It says “Pray for Sharks.” The meeting is informal but orderly. The first topic is back dues. There is a proposal that members must pay up before they are eligible to receive a trophy. This is only fair, and the amendment passes unanimously, the hands going up one at a time, cautiously.

“Okay, another problem,” says the president. “You know those little sharks we have on our trophies? Remember how last time the supplier didn’t have enough of them so we had to put those little men on? Well, I want you to know the sharks are on the way.”

“What do we do with the little men, then?”

“That’s up to you. Here’s the other thing: what about the patches. Do y’all feel satisfied with the way the club patches are?”

There is general agreement that the club patches are ugly.

“Not that the hammerhead isn’t as good a fish to put on there as any other,” someone explains, “it’s just that the people didn’t draw it too well. I had one and I threw it away. I mean it was that ugly!”

The meeting continues at this pitch. It is hard not to think of the sharks that are swimming tonight in the dark, moonless water three blocks from here, magnificently alert to the slightest shudders of change in their environment, but totally isolated from any awareness of the bureaucracy that is meeting to ritualize and reduce them.

Is it that unawareness, I wonder, that seems to give even a hooked and dying shark the upper hand? Though it will fight to the end of its strength, though it will gnaw at whatever is available even in the shallows of its own death, the shark radiates indifference. It does not care one way or the other, and a shark fisherman must eventually contend with that.

The rest of the meeting is taken up by a discussion of whether or not the women should be allotted a separate competition category for “most fish caught by a woman.” The proponents—all female—argue that this would give them a chance at a trophy, one that is not automatically snapped up by people like Paul Dirk. The men, by and large, don’t go for it. They see no reason why a woman cannot fish with the same expertise as a man.

“Ninety per cent of it is luck,” Dirk told me at his house earlier. “Once you get the bait on the hook, it’s just luck.”

The crisis subsides and the motion is tabled. The meeting draws to a close. Things are sluggish in the off-season, and there is an air of restlessness. Someone announces that there is a contest going on for trout and redfish. But nobody can get too thrilled about hauling in a two-pound trout, not when they’re used to throwing back anything under six feet.

Forgive this small irony. I’ve had to come to Galveston’s Sea-Arama to get a decent, close-up view of a live shark. Except for a few sand sharks, hardly larger than the mullet that drift in the swells on the beach, my first-hand experiences have been with dead or dying sharks, sharks out of their element, their grace subverted into obstinate fury.

Adjacent to the arena in which the dolphins are playing baseball with a man in a pirate suit there is a huge tank full of big saltwater fishes which lumber about morosely in the green water, skirting the circumference of a giant fishbowl dotted with viewing windows. There are groupers here, and sea turtles, and gars, and sawfish, and a lone leopard seal who cavorts among them, flaunting his warm-bloodedness.

And there are sharks. Five or six of them, swimming to the liquid strains of “Some Enchanted Evening” as it reaches them through the Muzak system. As a junior ichthyologist I am able to determine that these are either lemon or bull sharks, though I will not know for sure that they are the latter until I go home and look them up in a book. The largest is maybe six feet, a beautiful coal gray on top, modulating below to the color of the water. A remora swims steadily with it, attached to the shark’s underside by the suction cup on the top of its head.

What strikes me most about these sharks is their corporeality. They seem full-bodied, completed. They even seem to have an emotional dimension: those huge pectoral fins that hold them on course are endearing somehow. When one of them soars close to the window, that impossibly rough shark skin looks like velvet, and the shark itself, rather than appearing as a menacing mass of gristle, seems upholstered and comfortable.

Even the fatalistic shark grin is withdrawn, replaced with a look of consternation on some individuals, on others with a look of pensive brooding. I make a point of staring into the eyes of every fish that skirts by my window. The grouper’s eyes are a lovely, cloudy blue, like the photographs of the earth taken from far away in space; those of the gars are old and wrinkled and patient; but the eyes of the sharks are incredibly rigid, black on white, like the glass eyes in a taxidermist’s drawer.

Soon Vicki The Lovely Mermaid drops in from the top of the tank. She does a few cartwheels and begins to swim past the windows in the shark-infested water. The sharks do not eat her. They seem rather to congregate on the opposite end of the tank, making an effort to avoid her.

Watching her waving to the people on the other side of the glass I am struck by a phrase I have recently encountered. “Pray for Sharks.” And I do just that, because it is suddenly apparent that, for all their savagery and stalwart breeding, sharks are in trouble. Somebody is after them. Somebody, eventually, is going to try and take them away from us. Sharks are just too mean to be left alone.

I know it takes courage to swim in a tank of sharks and sawfish and turtles whose beaks could pry her arm off, but when Vicki swims by my window I just can’t bring myself to wave back.