This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Almost a thousand miles east of the political and geological turmoil of Mexico City lies Quintana Roo, the eastern state of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. Sometimes impenetrable, often mysterious, enabled by sea, terrain, and distance to keep much of the twentieth century at bay, Quintana Roo embodies the spirit of the Yucatán. The Yucatán Peninsula rises between the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea like a hitchhiker’s thumb, a slab of limestone—“living rock,” the Spaniards called it. Most of the ragged shelf is covered with jungle. In the north the dense foliage is scrubby, much like the monsoon forest of South Asia; in the south it grows increasingly lush until marshland and lagoon give way to towering rain forest. The peninsula undulates in the northwest Mexican state of Yucatán, climbs west into the mountains of Chiapas, stretches south across the border, and ends up in the mountains of Guatemala and Belize. Named for an independence leader who was also a poet, Quintana Roo captured my imagination long before I set foot there.

My journey through Quintana Roo began in Cancún. Armed with guidebooks (for Yucatán travel I favor Baedeker’s Mexico and Harvard Student Agencies’ Let’s Go: Mexico), tennis shoes, and a big hat, I ferried from there to Isla Mujeres and Cozumel, slept in the shadows of pyramids, bartered for tortillas in villages without electricity, and bused up and down the coast on a highway as straight and narrow as the road to heaven.

What follows are the highlights of my love affair with Quintana Roo, the coves and crannies that overflow with ruins, history, myth, and fish. End-of-the-world delights. Primitive escapes from telephones and plumbing. Isolated luxury beyond all pricing. Set no timetables, expect only the unexpected. In 1840 a separatist governor of Yucatán offered the troubled coastland to the republic of Texas in exchange for military aid. Consider as you float upon a sea as blue as the Big Bend sky that but for a glitch of history all this could have been ours—a fourth coast, the Texas Caribbean.

Cancun

Twelve years ago Cancún was a fishing village, an anonymous clutch of thatched huts important only to the hundred-some souls who hung their hammocks there. A mainland-hugging island adjacent to the village was notable for its dense overgrowth, a few ruined Mayan temples, and a population of monkeys and birds. That was before FONATUR, the Mexican tourism agency, had its computer spit out data to make a developer’s heart swell: one twelve-mile-long barrier island trimmed in sugar-white sand, cupped by two translucent jade lagoons, fronted by the Caribbean, and blessed the whole year with sunshine. A resort was born.

Aeroméxico’s margarita flight out of Houston arrives in Cancún just after noon every day. (Continental also flies from Houston, and American and Mexicana fly daily from DFW.) It’s a short flight; lunch trays have barely been cleared when the muddy brown Gulf gives way to the dense green of the Yucatán Peninsula. The plane continues to the eastern shoreline, crossing high above a solitary road running due south. Finally, before looping inland to the Cancún airport, you get a first glimpse of the aquamarine Caribbean. A scant two hours out of Houston Intercontinental, you step onto the runway and into the Technicolor tropics of Texas’ backyard jungle.

Once you’ve managed to get through baggage claim and customs (be sure to sign the back of your tourist card and to snag a porter, both time-saving tricks), there is very little that is complicated about a vacation in Cancún. You can drink the water directly from the tap. Desk personnel at most major hotels speak English. And for those who suffer beach burnout, ubiquitous travel agents arrange excursions to other islands and the ruins surrounding the resort. The result of all that efficiency: 80 per cent occupancy year-round. It’s fairly easy to find accommodations at Cancún City (on the mainland) anytime. If you want a room on the island, reservations are a must, but during September’s sprinkles—it never rains for long—even the resort hotels suffer a slump.

Vans that tote tourists from the airport to the hotel zone skirt Cancún City, a tediously planned community built to house the resort’s support staff. After turning east onto Paseo Kukulcán you will cross the garish green-blue Nichupté Lagoon to Cancún Island, the resort proper. A quarter-mile-wide hooked spit of land between the lagoon and the sea, Cancún Island is elaborately landscaped with topiary idols and lined with mock-Mayan hotels, modem shopping malls, calcimined condominiums, Moorish summer houses, marinas—and a golf course complete with Mayan ruin.

To get to town from the island, catch buses marked “Ruta 1” at paradas (“bus stops”) along Kukulcán. On the mainland side of the causeway, Cancún City offers its own restaurant and shopping drag (Avenida Tulúm). Wherever you go, prices are high, although they’re still less expensive than those at most North American resorts, and you shouldn’t expect any tremendous shopping bargains (most craft items are imported from Central Mexico). For the finest selection of goods from all over the country—from papier-mâché vegetables to silver jewelry—try Plaza México (Avenida Tulúm, next to Hotel America). For the tacky or the traditional—velvet sombreros, stuffed armadillos, wool sweaters—test your haggling skills at Ki Huic Market (Avenida Tulúm, next to the Municipal Palace) by bargaining down to at least half of the original price quoted. The most unusual shop in Cancún is Pacal (at the Hotel Plaza del Sol), a tiny boutique specializing in clothes and crafts from the state of Chiapas—Lacandon bows and arrows, hand-woven blouses, exquisitely carved figures of Indians in native costumes. Otherwise, shopping varies little from that in Houston’s Galleria.

Budget travelers check into hotels in Cancún City and commute to the beach. Hotel Tulúm (Avenida Tulúm 41, 988-3-05-53), Novotel (Avenida Tulúm and Azucena, 988-4-29-99), and María de Lourdes (Avenida Yaxchilán Mz. 14, 988-4-17-21) are not-quite-bare-bones accommodations that are central, comfortable, and inexpensive ($15–$20). Slightly more luxurious city hotels in the Marriott class are the Hotel America (Avenida Tulúm at Brisa, 988-3-15-00) and the well-worn Plaza del Sol (Avenida Yaxchilán 31, 988-3-08-88), both moderately priced ($25–$35).

But if you really want to experience the resort of the computer’s dreams, you must stay at one of the island’s beachfront hotels; just plan on dropping about $100 a day. There are those who refuse to set foot anywhere in Mexico unless they can get a room at that grande dame of Mexican hostelries, the hotel El Presidente. The El Presidente Cancún (Paseo Kukulcán–Hotel Zone, 988-3-02-00), with its glorious gardens, two swimming pools, a water sports marina, nightly salsa or mariachi music, and a location adjacent to the Pok-Ta-Pok golf club—illustrates why. Tourists interested in all-inclusive travel packages (in Cancún, unlike other parts of Mexico, packages are often the best deals) prefer the isolation and self-indulgence of the Club Méditerranée (for information call 800-528-3100). Strung along the Punta Nizuc Peninsula and designed to resemble an ancient Mayan city, the club is flanked by sea and lagoon. One price (around $1100 from Houston and Dallas for a one-week stay) includes airfare, lodging, meals, and most land and water sports. A hot spot for divers and snorkelers, the reef south of the club (part of the longest barrier reef in the Western Hemisphere) has been designated a national underwater park. Those with a taste for the pleasantly overblown can book into Fiesta Americana (Playa Caracol, 988-3-14-00). A Mediterranean-style villa gone mad, the multilevel jumble of pastel walls and tile roofs overlooks a placid sea and Cancún’s largest swimming pool.

Were I Jackie O. or even Lynn Wyatt, I would never stay anywhere in Cancún other than at the Camino Real (Paseo Kukulcán, 800-228-3000). A mere mention of the hotel’s name on the van ride from the airport evoked sighs from my fellow passengers, guests of other hotels. High-priced and sedate, the Camino Real is frequented mostly by wealthy Mexican families, businessmen, and honeymooners. The hotel’s food is some of the island’s best. Those who can’t afford the rooms ($130 for a double) schlepp over for the breakfast buffet.

Located at the northern tip of the island, the Camino Real’s pyramidal structure straddles a promontory that divides the sea into the reef-sheltered Caracol Beach and the rolling open sea of Playa Chac Mool. (Of the two beaches, the snowy stretch of Playa Chac Mool is the most impressive, but the undertow can be wicked; pay attention to warning flags.) Half the hotel’s rooms overlook Caracol and a private lagoon alive with sea turtles and behemoth fish. From the beach the rooms’ patios look like a stack of miniature stages that feature drying bathing suits and lounging couples. I prefer the seaside rooms, where balconies face nothing more complicated than sea and horizon and an occasional fishing boat. Windsurfing and sailing concessions, a trimaran dock, tennis courts, three restaurants, two beach bar-and-grills, and—most decadent of all—a swim-up pool bar round out the Camino Real’s offerings.

By day, people collapse on the island’s beach or float on the sea; waiters fetch drinks in slow motion. Deserted during the afternoon siesta hours, Cancún City comes alive when the sun sets. Streams of local teenagers in designer shirts (a Polo Shop recently opened in Cancún) ramble along Avenida Tulúm, shoulder-to-shoulder with businessmen in guayaberas and Mayan women swaddled in rebozos, all-purpose shawls that can also be used for carrying groceries or babies. Wizened campesinos gawk at red-faced and scantily clad young women who stumble and shriek, overwhelmed by too much sun or tequila. Tourists usually run in packs. Men in madras shorts trot behind women whose blanched strap marks crisscross their bare backs. Everyone seems to be in a hurry. Waiters scurry, crowds push and shove; there’s an air of expectation. Even children hustle to sell chicle, roses, and shoeshines.

The supper hour is the time to choose among several of the best restaurants in Cancún. For a peasant’s feast, head into Cancún City to La Parrilla (Avenida Yaxchilán 51), a popular grill. Don’t bother with the menu, here’s what to order: three or four tacos al pastor, palm-sized soft tortillas stuffed with grilled beef carved off a spit, cilantro, onion, and pineapple; guacamole, a mound as rich as it is green; grilled cebollas, lip-smacking sweet and crispy pearl onions; and a bowl of frijoles charolitos, a garlicky, smoky bean soup. Ladle a little of each of the two crunchy but not too hot salsas onto the tacos and into the beans, and squeeze lime over everything (about $3 total). Eat hearty, but save room for dessert; a genuine Italian pastry shop is just up the street. The hissing of the cappuccino machine—a sound seldom heard in the tropics—drew me to Pastelería Italiano (Avenida Yaxchilán 70), but it was the sopa inglesa, a traditional English confection of custard, strawberry jam, nuts, peaches, raisins, and meringue, that won my heart. On the island there’s the Camino Real’s El Restaurant Mexicano, a four-star restaurant in every sense. Its slightly Moorish, heavily carved wooden furnishings and elaborate wrought-iron candelabras are elegant; the plaster watermelons, vividly pink and green, are endearing. Yucatecan dishes and seafood are the mainstays of the menu, but innovative specials, such as coconut soup, carved mango salad, and freshly baked pumpkin bread, provide daily surprises. By all means, eat at El Mexicano as often as you can afford its north-of-the-border prices.

If you’ve got what it takes to disco in Mexico (practically a national sport), meander over to the Aquarius, next door to the Camino Real, to test your mettle. I did, planning to stay no longer than one hour. What followed was insane and exhausting. Dry-ice smoke billowed from the dance floor, and strobe lights freeze-framed dancers. Prince pranced across a giant video screen. A covey of olive-skinned Madonna look-alikes cooed, pouted, and squirmed. A bathroom attendant carefully arranged rows of powdered eye shadows and pots of glosses for the use of anyone with a few pesos. A chubby girl in a white satin mummy dress asked me if she looked fat. Floor-to-ceiling windows looked out upon the frothing surf pounding Playa Chac Mool to a disco beat. At four in the morning, sometime after the indoor fireworks display, I broke through the lunging line of bunny hoppers and ran for my room. Only later did I hear that Christine, a few hundred yards up the street, was where all the real action was that night.

Breakfast at the Camino Real is the best reason for getting up early when all you have planned is a day of doing nothing. Request a table on the patio of Azulejos restaurant, where grackles flash blue-black against the pink and orange of tropical blossoms. The legendary buffet stretches beyond all reasonable appetites. Consider the selection of fruit juices alone: watermelon, orange, melon, papaya, grapefruit, grape—all freshly squeezed. For those who can’t do justice to the big spread, the menu’s El Maya breakfast is a good bet, with huevos a la motuleña (fried eggs atop a corn tortilla heaped with black beans, chiles, salsa, cheese, and a few obligatory green peas), pan dulce, fried plantains, coffee, and juice (about $5).

Isla Mujeres

Isla Mujeres, two miles east of Cancún, was discovered in 1517 by Spaniards who named it the “Isle of Women” for a cache of terra-cotta figurines representing the fertility goddess Ixchel, or so the most popular story goes. Another version says that the explorers were inspired to name their discovery for the lady loves of pirates, who were often left to stew on the island while the menfolk pursued the plundering business. Believe what you will about its past, the tiny (five miles long, one mile wide) island’s solitary village is still little more than a sleepy lair of pastel clapboard houses fronted by sparkling water, where a dozen randomly anchored rowboats look like cast-off slippers. Schools of snorkelers spout and splash around the island’s reefs by day, but when the last of the tour boats pulls out at dusk, only the most amphibious of travelers—seasoned divers, displaced surfers, and thrifty Europeans enamored of the cheap beach camping—are left in town.

The most romantic way to arrive in Isla Mujeres is to be nestled in the prow nets of a trimaran, suspended a few feet above indigo and verdant water, while red and yellow sails billow and snap overhead. Trimaran trips to Isla Mujeres can be arranged at the Camino Real, El Presidente, and other hotels in Cancún; the price for a round-trip ticket (about $20) includes lunch and snorkeling gear. You may be able to negotiate a one-way ticket if you wish to stay on the island overnight. Romance aside, 25 cents will get you to the island on passenger ferries that depart Puerto Juárez—a ten-minute cab or bus ride from Cancún—every three hours from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. The last ferry back to Cancún usually leaves Isla Mujeres at 5:45 p.m., but check the schedule.

A typical day begins with huevos rancheros at the Miramar (north of the ferry dock); some mid-morning windsurfing at Playa los Cocos, the island’s sandy northern beach; a noon walk of ten paces to Palapa Cocos for what might be the best papas fritas (fried potatoes served with lime) in the world; an afternoon ride on mopeds (for rent at most hotels around town) to the southern tip of the island and El Garrafón reef for snorkeling; a little late-in-the-day snoozing on the beach; and finally, after such a day of hard work, an all-out splurge on fresh ceviche caracol (conch), pleasantly astringent lime soup (limes, chicken, chiles, tomato, and tortilla strips), and grilled shrimp at Gomar (Hidalgo 5 at Madero), one of the oldest restaurants in town—and maybe the best.

From swimming to eating, all of the town’s most popular activities are connected in some way with the sea. Indeed, the best place for a good night’s sleep is on the beach, or at least close enough to feel the ocean spray. My candidate for an inexpensive hotel is the Rocamar (two blocks inland from the pier at Bravo and Guerrero, 988-2-01-01). For a saltier sleep you would have to bunk on a boat. The nautical theme is pervasive; lacquered ropes substitute for banisters, conch shells line the walkways and serve as path lights, while nearly every countertop is inlaid with mollusks. The breezy rooms—the top floor is preferable—are pleasantly broken in, and the bay windows and decks look out on the east beach (which is craggy and too rough for swimming). All in all, it’s a sailor’s delight.

Playa del Carmen

Playa del Carmen, 41 miles south of Cancún, is an eccentric, bustling little village of thatched huts and cement-block fruit stands, an assortment of casual to ramshackle inns, a backpacker’s campground, and a couple of incongruously pricey beach hotels. Its streets are filled with schoolchildren, divers, orange-juice vendors, gossiping shopkeepers, and an international assortment of young people wearing pet parrots or monkeys and little else. The only street from the highway cuts through the heart of town to the bus depot and a whitewashed plaza before dissolving into a platinum beach sloshed by rolling turquoise surf—one of the most inviting swimming spots along the coast.

For years Playa del Carmen was a well-kept secret among divers, but in the last decade (thanks mostly to a dock plied by Caribbean cruise liners and the Cozumel ferry) the village has become a haven for laid-back entrepreneurs. A dozen cane-sided restaurants (including Restorante Bocca, an Italian pizza parlor) have a Gilligan’s Island aura about them, while the fare, generally fresh from the sea, is simple and elegant. The best place for a quick, inexpensive bite is Restaurante de la Nuestra Señora, next to the bus station. The menu is pretty much limited to fish and egg dishes, but the pescado mojo de ajo (the day’s catch broiled in garlic and butter) arrives with rice, beans, cabbage, tomatoes, salsa, and a stack of tortillas hot off the comal—a fresh, stick-to-your-ribs meal for about $1.50.

Also near the bus station is El Kundalini, a magical restaurant a block south on the street behind Posada Lily. Gilligan would have given his sailor’s cap for a share in this cafe, a breezy cane palapa (“hut”) decorated with the art of explorer Frederick Catherwood, Mary Poppins prints, and turn-of-the-century photos of scantily clad nymphets. But if there’s a castaway air to the decor, the dishes that emerge from the kitchen are as refined as those of nouvelle cuisine masters anywhere. Less than a year ago the proprietor, chef, waiter, and busboy, a Dustin Hoffman look-alike, traded the stress of his Mexico City restaurant for four canted tables and the romance of the seaside. In a kitchen the size of a closet he turns out delicately flavored renditions of traditional favorites. Road-weary and peso-poor, I landed on his stoop late one night and only his kindness and quesadillas (melted parmesan and Mexican cheeses spiced with oregano and cilantro, wrapped in soft, thin wheat tortillas and ladled with a sauce of avocado, fresh cream, and chiles; four for $1) put me back on my feet. “The locals don’t like my cooking,” he complained, in answer to my praise as he took my order with a quill pen. “They say it’s ‘muy rico, muy dulce’ ” (“very rich, very sweet”). Even so, El Kundalini’s tables are usually full, especially in the morning, when bronzed Caribbean loungers with continental accents stroll in for a breakfast of mandarin juice, fruit salad with honey and yogurt, soft-boiled eggs, French bread, marmalade, thick black coffee, and sweet cream. The view may be of chickens and pigs, but the menu evokes candlelight and roses.

Most visitors pass through Playa on their way elsewhere; I can easily imagine a lifetime of stringing shell necklaces to sell to the bandy-legged cruisers who leave the ship in search of something, anything to buy. A couple in matching straw hats, knee socks, and shorts asked me what I had found to do in town. In lazy good spirits I shared my greatest secret: the best popsicles in the Yucatán are at Paletería y Nevería la Flor de Michoacán (one sign says “Restaurant Edith,” but it isn’t), across from the bus station. Mexican popsicles, paletas, are 99 per cent fresh fruit with a splash of fruit juice or milk to freeze them on sticks (about 15 cents each). My favorite was coconut, so thick with fruit that I spent more time chewing than licking. I eventually tried all the flavors—hibiscus to watermelon.

If you’re planning to catch the last ferry of the day to Cozumel (at 6 p.m.), arrive early; tickets go on sale at 5 p.m., by which time a long line of mainland commuters has already formed. (Less-crowded ferries depart at 6 a.m., 10 a.m., noon, and 4:30 p.m.) Buy your tickets and sit back to watch the locals work the dock. Thirty minutes before passengers disembark, vendors of everything from blankets to doughnuts (fresh batches are delivered throughout the day) jostle for space between incoming boats and waiting taxis.

Should you decide to stay, the best of the moderately priced hotels is the Maranatha, a couple of blocks from the highway on the main road into town. Brand-new and positively lavish by Mexican Caribbean standards, the Maranatha offers thick towels, king-size beds, air conditioning, and hot water for about $12 double. Luxury hotels—overpriced and overrated—flank the dock. Economical quarters can be found on the beach north of the dock, but most are suited only to the truly bohemian (or the broke). One of the most popular with the French and German backpacking crowd is La Ruina Cabañas, a compound of huts that are little more than covered hammock hooks (bring your own hammock), with outhouses and something resembling a shower. If you can survive the mosquitoes, eat at La Tarraya, an open-air restaurant a few paces up the beach. Drop a few pesos on the shrimp ceviche and the pescado entero frito (whole fried fish of the day), and you’ll be convinced that you are living in the lap of luxury. Such illusions are what Playa del Carmen is all about.

Cozumel

Centuries before Jacques Cousteau introduced the magnificent reefs of Cozumel (fifty miles south of Cancún) to the world, Mayan women made pilgrimages to the Island of Swallows, pitching across the sea in canoes launched from Polé (now Playa del Carmen) to the sanctuary that some consider the Mesoamerican equivalent of the Garden of Eden. Many island shrines were dedicated to the goddess of fertility, but few survived the idol-smashing visit of Cortez in 1519. Although Cortez moved on to bigger things, he was followed in 1527 by Francisco de Montejo, a soldier of fortune who made the island a base for his bid to conquer the Yucatán. Finally abandoned by the Spanish in the seventeenth century, the isle became a favorite hideaway of pirates Jean Laffite and Henry Morgan.

Today little evidence of either conquistador or pirate remains. Though several minor Mayan shrines have been discovered, most were demolished by Americans during the building of a World War II air base, which is still in use (Aeroméxico and Continental fly direct from Houston and American flies from Dallas). The island’s modern town, San Miguel de Cozumel, is neither charming nor slick, and the landscape north and south remains much as it has always been—an unrelieved stone shelf covered with dense, scarcely populated scrub jungle and surrounded by the most limpid water of the entire Mexican Caribbean.

For the visitor, life in Cozumel is not unlike that aboard a cruise ship. Though the island stretches 28 miles long and 11 miles across, hangouts are few; by the second day all faces seem familiar. Daily choices are simple: what to eat, where to lounge, how much to drink. The amenities remain the same, but the ambience depends heavily on who’s in town.

The quickest way to size up the character of the current crowd is to drop in just after sunset at Carlos ’n’ Charlie’s (north of the dock on Rafael Melgar, above the Aeroméxico office). Inside the narrow loft you’ll find tables, stools, benches, and settees overflowing with sun-bleached California divers, Wisconsin honeymooners, giggly sorority girls, Houston yuppies, even mamas and papas flanking daughters. Central to the hubbub are Tarzanish waiters who seem hired to lust (and be lusted after). Table-hopping and margarita-slurping are the big draws, along with a good deal of babble and bluster, until around midnight when—mixes and matches made—almost everyone is off to Scaramouche (Rafael Melgar at Adolfo Salas) to disco till dawn.

Days are for recovering, sleeping on the beach, taking Robinson Crusoe excursions to deserted islands (depart from hotel El Presidente), going on diving trips, or just lolling in the water. The best beaches, as well as the luxurious hotel El Presidente (800-854-2026), are south of town. My favorite hangout, Playa de San Francisco, offers a samba band, wooden beach chairs, a palapa restaurant (with unlimited shrimp ceviche), and roving cocktail waiters. For diehards, daytime mingling is best at El Presidente (all Mexican beaches are public, even those fronting hotels), where beachfront burgers taste like those at home, for about the same price.

Those with water on their minds come to Cozumel to dive at the best reef this side of Australia, the renowned Palancar. Diving trips can be arranged by different shops all over town and by most hotels, but Cozumel is no place to learn the sport. Beginners should stick to windsurfing and snorkeling. In the water off the beaches of El Presidente and La Ceiba hotels, schools of fish work over snorkelers bearing bread. Offering balls of dough to pale blue fish with violet-rimmed eyes, hook-nosed parrot fish, and painted and smirking clown fish, I watched hundreds of the same fish you see for sale at a quarter a fin in pet stores.

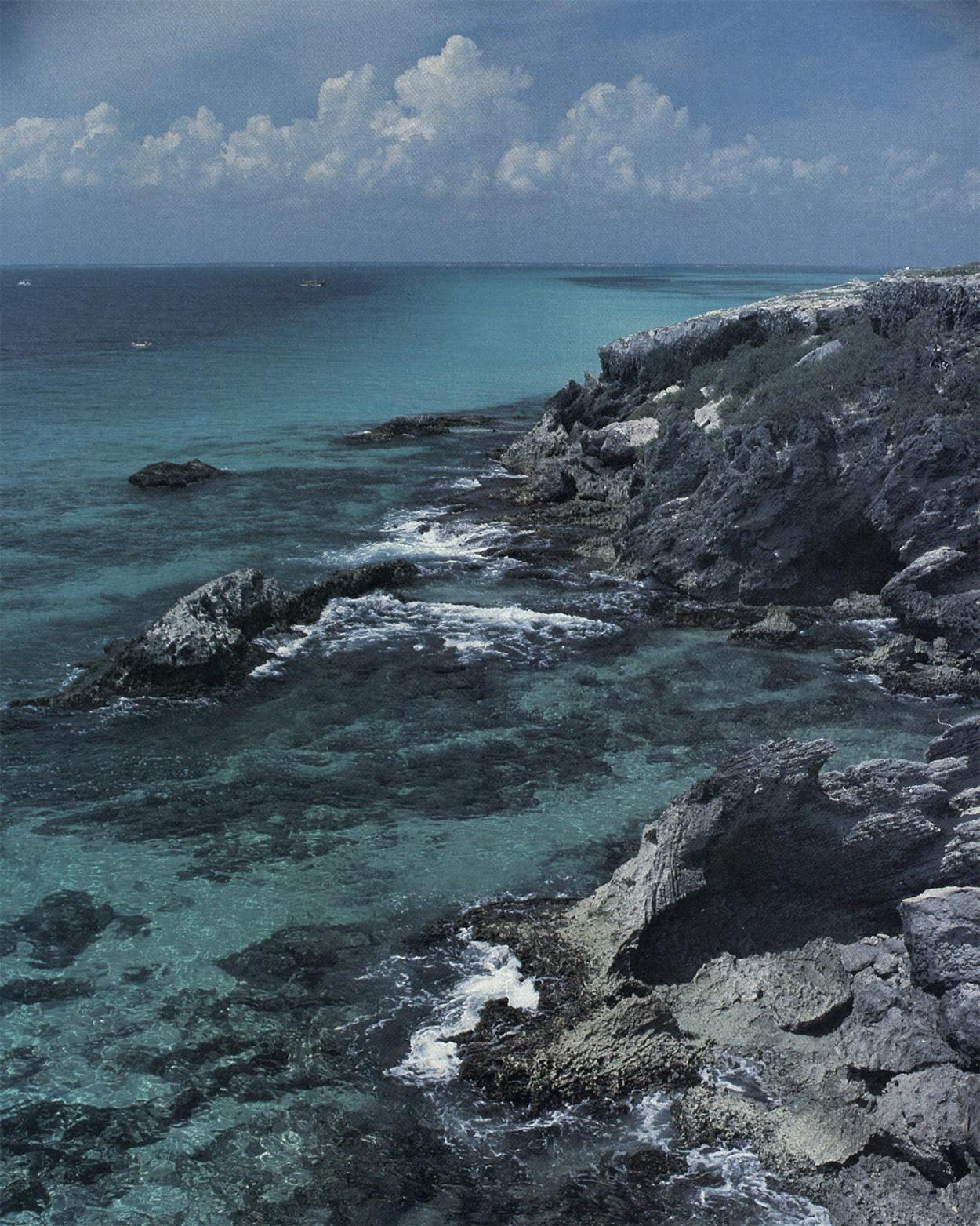

The most economical way to get around the island is to rent a moped ($10–$15 a day). Rates in town are often lower than those at beach hotels (the best were at Suites Elizabeth, Calle Adolfo Salas 3-A, 987-2-03-30); just make sure you get a full tank of gas and a working set of gadgets (horn, lights, brakes). Island roads are narrow, rocky, and shoulderless, but speeding cabs are the moped driver’s biggest hazard. Once you’ve got wheels, a trip around the southern tip and along the windward side of the island is a must. The open sea crashes along a rocky shoreline—not safe for swimming, but a few sheltered coves offer good picnicking possibilities. For further exploration, pick up a map to various ruins (really ruined, for the most part) at the tourist information gazebo on the town plaza.

Hotel accommodations along Avenida Rafael Melzar range from the self-indulgent and pricey beach hotels (El Presidente, La Ceiba, Mayan Plaza) to the comfortable-with-great-views (Barracuda, Vista del Mar) and the central, sometimes spartan, affordable, in-town hotels. Of the latter, the Hotel Aguilar (Avenida 5 at Calle 3 Sur; 987-2-03-07; $17) is the most endearing bargain—clean and cheap with a walled garden, air conditioning, a pool, and hot showers. A word about showers in Mexico: outside of major resorts (and sometimes even there) hot water can be scarce. The problem is compounded with confusion over taps; when designated “H” and “C,” “C” usually stands for caliente (“hot”). A tap marked “F” is always frio (“cold”). Sometimes hot water is available only early in the day. Often you get all hot or no hot. I always rate hotels by their showers; the Hotel Aguilar rates four stars in the shower department, with admirable water pressure a plus. The towels, on the other hand, are almost transparent. Bring your own.

Of the restaurants in town, Las Palmeras (across from the ferry dock) is a longtime tourist favorite, but pass up the Blub sandwich in favor of the sweet heat of chicken en mole. The open-air waterfront restaurant is a good place to sit out the siesta hours, sipping licuados, blender drinks of fresh fruit. Sandía (watermelon) licuados are light and sweet, and blends of banana or papaya with milk go a long way toward filling the gap between lunch and the traditional late supper. Just up the quay, Jimmy’s Kitchen serves admirable renditions of Yucatecan specialties in a dining room at the back of Carlos ’n’ Charlie’s—a quiet back seat to the front bar. El Portal (at the dock) looks and is touristy, and though you pay for it, the food and the service are generally excellent. Grilled fish is the house specialty, but even the Mexican plate is memorable (banana-leaf tamale, guacamole, skirt steak, mole, and Yucatecan salsa made with the fiery chile habañero). The best restaurant off the tourist strip is Restaurante Bar Pancho Villa (Calle 2 Norte), two blocks behind the plaza. Ask to sit in the courtyard dominated by a tree as big around as an elevator. It’s all rather shabby, but service is gracious, and the crowd of locals proves that the food is deliciously authentic and cheap. Begin your meal with the thick, smoky chipotle sauce and chips followed by consomé de Pancho Villa (a rich chicken soup full of meat and vegetables) and finish up with grilled conch (chewy and rich). Be forewarned that dinners are served with side dishes of cabbage, rice, beans, potatoes, and carrots—they’re only for the ravenous. At the end of the meal the proprietor brings you a nip of xtabentun (pronounced “ish-tah-been-toon”), a traditional Mayan liquor smelling of anise and tasting of honey (it’s sold all over the Yucatán), then leaves you to ponder and digest, order a round of coconut liqueur, or stare at the stars and plan the rest of your days. Take your time; the check will not be presented until you ask for it—the most ingratiating of Mexican customs.

Tulúm

Several times a day buses roar out of Cancún headed for the ruins of Tulúm, a Mayan city by the sea, eighty miles to the south. A first-class ticket ($1) assures you a seat and sometimes air conditioning for the hour-long trip. Traveling second class is more colorful and only slightly less comfortable, unless you’re standing in the packed aisle.

The bus stops at El Crucero, a crossroads restaurant three quarters of a mile west of ancient Tulúm. From there it’s an easy ten-minute walk to the ruins, but a cold beer (Negro León is the regional brew) and a bocadito (“little bite”) make the blazing sun more bearable. El Crucero may seem an unlikely spot for a satisfying peasant’s lunch, let alone tablecloths and Vivaldi, but serendipity is the rule in Mexico.

The founding date of Tulúm (or Zamá, “daybreak,” as it was originally named) is unknown. Tulúm, which means “fortress,” was a ceremonial city and a religious center, but unlike other Mayan sites it was also inhabited. The grid of streets that once ran across the city is often discernible. The present structures are thought to date to late in the Postclassic or Decadent Period, 1200 A.D. to 1450 A.D. The walled city was occupied as late as 1544, when the chaplain of a Spanish expedition sailing along the coast wrote, “Toward sunset we saw from afar off a town or village so large that the city of Seville could not appear greater or better; and in it was seen a very great tower.” Though the city’s inhabitants signaled the ship to approach, the startled captain chose not to land. It was left to the intrepid John Lloyd Stephens, who cleared and explored the ruins in 1841, to introduce Tulúm to the world. He did so in an absorbing account called Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatán, illustrated by Frederick Catherwood.

The entrance to the ruins is the southernmost of five archways built into a rock wall that was originally 10 to 16 feet tall and 23 feet thick (it’s but a sliver of its former self). Tickets to the site (about 30 cents) are sold just beyond a gypsylike village of market stalls. As far as Mexican archeological sites go, Tulúm isn’t large; it’s easily explored in a few hours, and unlike the massive temples of Chichén Itzá and Uxmal, the structures are of an unimposing size. Mayan men of various ages stand ready to offer their services as guides, frequently asking tourists, “Are you interested in hearing our side of the story?” Guided tours can be illuminating, confusing, or purely romantic, but they are almost always entertaining. Prices are negotiable. Usually I prefer to stumble around on my own, camera in one hand, guidebook in the other.

The two-story Temple of the Frescoes houses a remarkably vivid mural depicting several important Mayan divinities. In a niche of the building’s facade is a carving of the god most closely associated with Tulúm—a jolly winged, inverted figure known simply as the Diving God. Scholars suggest that the figure is a bee god, highly likely since Tulúm skirts the jungle called Ekab, or “home of the black bees.” In Mayan times honey was used for everything from the sacred drink to mortar.

For the most impressive view of Tulúm you must climb the broad stairs leading to the top of El Castillo, the site’s largest structure. The clear blue Caribbean (the buildings were originally painted a matching shade) lies some forty craggy feet below. The walled compound sits at the foot of what must have been the “tower” of the Spanish padre’s account, and to the north and south the rugged and isolated coastline remains untainted by time.

Although it is possible to romp through the ruins of Tulúm in an afternoon, it seems more appropriate to make a day of such an outing, with swimming and picnicking at the pristine beach three and a quarter miles south. Should evening catch you unsheltered, the best place to spend a night (or several) is just a short ride up the beach. You’ll want to hail a taxi at El Crucero (the trip runs about $3, an outrageous price in these parts, but it’s a long, hot walk through the jungle by day and a pitch-black obstacle course at night).

The beach south of Tulúm is dotted with a low-rent variety of accommodations—palapas, tents, bungalows, and cement cubicles. Of the erratic lot, Cabañas Tulúm is far and away the most well-appointed and romantic, as close to a desert island hideaway as you can get and still have running water. In fact, for $12 the amenities are plentiful: private bathrooms with showers (no towels), reasonably comfortable beds, porches with hammock hooks, and a restaurant. The eighteen blue-and-white stucco-and-tile duplexes perch atop white sand dunes and beneath coconut palms, a hundred yards from the sea. Sure, the surf roars and the wind whistles, but that only reinforces a glorious sense of isolation.

Don’t expect hot water; it’s solar-heated during the day (who needs a hot shower on the beach?). And the restaurant is a casual catch-as-catch-can affair, where the food ranges from splendid to unrecognizable. For the best time at Cabañas Tulúm, bring a well-stocked picnic hamper, mosquito coils, and candles—the electric generator operates from dark until 11 p.m. You can’t expect the end of the earth to be civilized.

Cobá

In Cobá (107 miles southeast of Cancún), the rising and setting sun controls the pattern of daily life. Men, women, children, chicken, turkeys, and dogs rise at dawn. Pigs wake when they please, only to trot down the single, unpaved street and belly flop in a favorite mudhole. By the time the midday heat settles in—dense and droning so far from the sea breezes—all is quiet again, villagers sheltered in their jacales or swinging in hammocks, pigs and dogs dozing in the street. So it goes, until at dusk exotic birds dart from the jungle in formation, a chattering salute to day’s end. The sun disappears behind the tallest pyramid in the Yucatán. Fireflies and candles scarcely disturb the total darkness that follows.

Near the village is Lake Cobá, one of six shallow bodies of water that attracted the Maya sometime before 623 A.D., the date of the earliest stela. The ruins—remains of six thousand buildings—near modern Cobá cover an area of eighteen square miles. Around the lakes and through the jungle the Maya built sacbeob, broad white roads. The limestone-paved system is still faintly visible through the jungle, though to see it one must climb the seven-tiered El Castillo to its summit (enter the site and walk straight ahead for about fifteen minutes to the path marked “Grupo Nohuch Mul”). For the best view of the surrounding lakes, follow the signs to Grupo Cobá (just inside the gate and to the right) and climb the Temple of the Church.

The ruins are open daily, but few visitors come, and the jungle constantly reclaims what archeologists uncover. A scant 5 per cent of the site has been excavated; hardy adventurers could easily spend weeks exploring the broad maze, listening to the howler monkeys, sidestepping coral snakes, spying on green jays and parrots (bring binoculars), and slapping mosquitoes (insect repellent is a must). Cleared hiking and bicycle paths (bikes are for rent outside the entrance gate) crisscross the grounds between the most-visited temples, but the rest of the site is grandly ruinous, sometimes completely overgrown. Pith helmet and khaki shorts would not seem out of place.

Lazing on the north shore of Lake Cobá is Club Med’s Villas Arqueológicas, an oasis of manicured grounds and air-conditioned rooms. The Villas Arqueológicas have little in common with Club Med’s amenity-rich resorts, but they are well-appointed hotels licensed by the Mexican government to provide first-rate accommodations at many of the country’s archeological sites. This hotel offers as many excuses as you’ll need to hole up in Cobá for a few days: hot showers, tennis courts, a bar, a swimming pool, even a well-stocked library and a relief map of the ruins (for reservations call 800-528-3100). It’s pricey by Mexican standards ($34), and the chef sometimes fails to overcome the limitations of his outpost. Never mind. Just step out the gate and around the corner to Juan Isabel’s for polio pibil (chicken marinated in sour oranges, spiced with saffron and achiote, and baked in banana leaves) or whatever else Señora Isabel is cooking that day. Though there’s not a lot of variety, it’s easy on the budget.

All Shangri-las have their price, and Cobá can be devilishly difficult to get to. It’s no problem if you rent a car in Cancún; just drive south out of the city on Highway 307 and veer right a mile past El Crucero. The wheelless can walk a mile south from El Crucero to the Cobá cutoff to flag down the bus that is rumored to turn in there at six in the morning and noon. However, after sitting on my duffel bag for a couple of hours under a mad-dog sun I hitched a ride into Cobá (Highway 307 swarms with americanos in rented Jeeps and Volkswagens). Getting out of Cobá is slightly less problematic; day visitors to the ruins and guests departing the Villas Arqueológicas are usually happy to take on riders.

Chetumal

The only reason for taking the bus ride from Cancún to Chetumal (235 miles south of Cancún and five hours of hot wind and monotonous scenery), unless you’re on your way to Belize, across the Rio Hondo border can be found in the jungles that entwine the capital city: little-known and seldom-seen Mayan ruins, inky blue lagoons, and perfectly round, depth-defying swimming holes called cenotes (“sinkholes”). To ferret out such glories you have to be resourceful, preferably with access to a car (Chetumal’s one car rental agency can be found in the hotel El Presidente), and you should venture forth armed with maps and guidebooks.

If you decide to make the trip by bus, pack snacks and reading material; I longed for both soon after passing Tulúm. Halfway to Chetumal the bus stops at Felipe Carillo Puerto, a historically important town dominated by a pink municipal building and a vast town square. Originally known as Chan Santa Cruz (“Little Holy Cross”), the village was founded during the Caste War, which broke out in 1847 and pitted the Maya against Ladino landowners. The town was the headquarters of the Cruzob, Mayan rebels who rallied troops with the help of a talking cross (and a convincing ventriloquist). Within a year the Indians had taken most of the peninsula and were ready to march into the capital city of Mérida when at the sight of winged ants, harbingers of the spring rains, they scurried off to plant their corn. The Maya were driven out of Little Holy Cross in 1901 but were allowed to resettle the city at the end of the war.

Still standing on the main plaza is the church built in 1858, where the talking cross held forth. Young boys parade in front of it, dashing across the square to tease the girls selling tacos, fruit, tamales, and ice cream to travelers who pass up the station’s 25-cent blue plate special. As usual in Mexican bus stations, there was such a crowd that I felt as if the country’s entire population was on the move, with neatly crimped sacks, roped boxes, and Nike gym bags in tow. Though every mile of my journey showed in the stains and wrinkles of what I wore, the Mayan women, almost always traveling with children, remained uniformly pristine in their brightly embroidered huipiles—white, knee-length, square-necked blouses worn over eyelet-trimmed mid-calf-length petticoats.

Back on the bus and seventy miles south of Felipe Carillo Puerto, I got my first glimpse of Lake Bacalar, a ribbon of blue snaking through the foliage a couple of miles to the east. The lake, also known as the Laguna de Siete Colores (Lake of Seven Colors), roughly parallels the highway for 35 miles. Near its southwest end is the village of Bacalar, noteworthy for its lakeside beach and the Fuerte de San Felipe. The fort, which overlooks the lake, was built by the Spanish in the seventeenth century to ward off pirates and was put to good use as a rebel outpost during the Caste War. It now houses a small museum.

Arriving in Chetumal around three-thirty in the afternoon, I found the city with its hatches battened and its shops and businesses closed as they are every day from one to five. The extended siesta is more than sensible, given the port’s paralyzing heat. During the time the streets are empty, the clean-swept, landscaped boulevards evoke the Miami of the late fifties. Nevertheless, the city does have an ancient soul. Born as a Mayan boat-building center called Chactemal (Where the Redwoods Grow), the abandoned city was reincarnated in 1898 as a Mexican military port. Few buildings in town attest to the city’s age because it was almost completely leveled by hurricanes in the forties and fifties.

The most frequent visitors to this duty-free port are Mexicans who come to buy Japanese stereos and televisions. The only bargains for norteamericanos are soft cotton Chinese shoes (about $1.50) and olive oil ($3.50 for two pounds). Otherwise, the little open-air shops lining Avenida de los Héroes, the city’s main drag, overflow with cheap plastic goods and tins of imported foodstuffs.

There is a certain charm to the Sergeant Pepperesque military band that plays in the seaside gazebo on Saturday nights; the coconut ice cream cones sold at the Bacalar bus stop are magnificent; and La Ostra (two blocks west of the bus station, on Gandhi) is a good place to try the Mayan specialty dish relleno negro (a black stuffing of ground pork, pimiento, olives, eggs, epazote, and vinegar, usually served with chicken). But to be truly happy you made the trip south, return to Lake Bacalar and Hotel Laguna (just south of Bacalar village, on the lakeside drive, no phone, $12). Local buses, which are really vans, depart Chetumal for Bacalar every hour, more or less, from two blocks north of the main bus terminal (behind the market; ask directions to the combi). The van to Bacalar will drop you at the hotel.

Fed by ground streams and swamps, Lake Bacalar encompasses several cenotes, circular cutouts where the limestone crust has collapsed into an underground river. Hotel Laguna, overlooking one of the lake’s hauntingly beautiful steel-blue sinkholes, is the newest waterside kingdom of Carlos Gutierrez, the builder of the seaworthy Rocamar in Isla Mujeres. Gutierrez sold the Rocamar and began building the hotel of his dreams on Lake Bacalar, and Hotel Laguna is the ultimate in resort rococo-kitsch. Gutierrez’s signature conch shells encrust the walls and the ceilings of the public rooms, the pool, and, of course, the bathrooms. His new passion—hand-painted tiles offering sage advice, Mexican philosophy, and bawdy humor—fills any gaps. Many of the tiles address the drinker: “For all that is bad, mezcal; and for all that is good as well.” True to such sentiment, there are three bars and only thirty rooms. When the hotel isn’t crowded, drinks may be on the house. It’s closer to a gingerbread kingdom than a luxury resort, and Gutierrez runs the place with a single long-faced waiter and a short, rounded desk clerk (who stands in as a cook on Sunday nights). Hotel Laguna’s poolside decks (ideal for parrot watching) and cotton candy sunsets go a long way toward making a visit to Chetumal and environs worth the effort.

When it’s time to leave Chetumal, you might consider taking a local flight back to Cancún or even to Mérida, the capital of the state of Yucatán (from time to time Aeroméxico offers specials, such as flights to selected Mexican cities for $1, but reservations must be made when you purchase a round-trip ticket out of Houston). Then again, you may find yourself darting on and off Highway 307 indefinitely, forever on the lookout for another lagoon, an unexcavated ruin, an untouched stretch of beach.

Barbara Rodriguez is a freelance writer who lives in Blanco.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Mexico

- Longreads