From its headwaters in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado’s Southern Rockies, the Rio Grande makes its way across New Mexico and into Texas, coursing through some of the country’s farthest flung landscapes. The most renowned and scenic area along the storied river’s nearly two-thousand-mile path to the Gulf of Mexico is the rugged and mountainous Big Bend country, in far West Texas.

Paddling the Rio Grande through deep limestone canyons in the remote reaches of this isolated and wild land makes for the most picturesque river trip the state has to offer. And I’ve wanted to experience the dramatic natural grandeur of such an adventure for as long as I can remember. The seeds of this dream were first planted decades ago in, of all places, the offices of Bowmer, Courtney, Burleson, and Pemberton—my father’s law firm, in downtown Temple. There, adorning the hallways, were striking sepia-toned black-and-white photographs of the Big Bend region.

The images belonged to Bob Burleson, a partner at the firm and a devoted conservationist. He served on the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission; founded the Texas Explorers Club, which helped lobby for the establishment of Guadalupe Mountains National Park; headed the American Whitewater Affiliation (now American Whitewater); and coauthored Backcountry Mexico: A Traveler’s Guide and Phrase Book. I recently learned that Burleson also wrote one of the early guides to paddling the Rio Grande through the Big Bend, which was first published serially in the American Whitewater Affiliation’s magazine and later by the National Park Service. He even once guided U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, another committed conservationist, on a Rio Grande canoe trip in the early sixties and, later, steered him to other natural wonders across the state. These explorations would become the basis for Douglas’s 1967 book Farewell to Texas: A Vanishing Wilderness.

The eye-catching photographs of the mountains and gorges of the Big Bend region, and the ribbon of river that carves its way through them, embedded in my childhood imagination and have remained there for some fifty years. Unlike Bob Burleson, however, I’m not an avid canoeist. I enjoy camping, and I like the water. But my paddling experience is limited to occasional afternoon excursions on the Guadalupe River, especially during the summers when my daughter attended camp in the Hunt area, and on Lady Bird Lake, in downtown Austin. I grew up the youngest of three boys and trailed my middle brother by seven years and my eldest by eight. I’ve heard stories and seen photos of a few canoe trips that my dad and brothers took in Central Texas and Arkansas, but by the time I would have been more than just whiny deadweight, such excursions had, sadly, come to an end.

This past spring, I decided enough was enough. The time to embark upon an epic Rio Grande canoe trip through Santa Elena and the other towering canyons of Big Bend had finally arrived. The long wait was over—or so I thought.

Considering my lack of real experience, coupled with my lack of a canoe, I decided to seek a professional outfitter. But after placing a few calls in March, I quickly realized that the current drought is especially severe in the Big Bend region. The Rio Grande is suffering extremely low flows and has completely dried up in some areas. Several of the guides I spoke with had begun limiting their outings to day trips.

A tip from a colleague led me to Mike Naccarato, at Far West Texas Outfitters. He had guided with another Big Bend–area service until March of 2021, when he set out on his own, catering to smaller groups, offering top-notch dining options, and providing customized experiences. Naccarato said he was game to take me on a trip. On the phone, we went over various options, with the river’s current conditions front of mind. There were really no good options in the Upper Canyons, in Big Bend Ranch State Park nor in Big Bend National Park, he said. The Great Unknown, a stretch in the national park, was out. And Santa Elena Canyon, the most popular trip, a bucket-list destination for many canoeists and one that typically offers strong boomerang options, was also out. It was so dry when we spoke that it was basically more of a hike than a boat trip.

But all was not lost. If we started a bit farther downstream, where springs feed the Rio Grande, increasing its flow, we could do anything from a four-day Boquillas Canyon run to the more intense Lower Canyons trip, considered one of the best canoe excursions in the U.S. The latter would require a seven- to ten-day commitment, so we decided to paddle just the first leg, a two-day, eleven-mile segment that would take us through the majestic Temple Canyon.

Early on a beautiful mid-April morning, near the historic Gage Hotel, in tiny Marathon, Naccarato pulled up in his white four-door Toyota Tundra, loaded with two canoes, paddles and other gear, provisions, and a sackful of breakfast tacos. I’d enticed a buddy, Mark Harris, a former magazine colleague, to join me. He’d never made the trip either, so it didn’t take too much arm-twisting to persuade him.

Mark and I brought only sleeping bags, sunscreen, clothes, and booze and beer. Naccarato took care of the rest, including dry sacks, food, ice, water, and cushy inflatable sleeping pads. He also packed a three-person tent, but because of the favorable weather forecast—clear with lows in the upper 50s—he didn’t think we’d need it.

After driving south for about an hour from Marathon, we arrived at our put-in at Heath Canyon Ranch. Right across the river, in Mexico, is La Linda, a ghost town comprising just a few deteriorating buildings—including

a stark white church. Connecting the two countries is a one-lane bridge built in 1964 by Dow Chemical, which operated mines in the area. Those shut down in the eighties, and the bridge was closed in 1997. On the Mexican side of the Rio Grande was a small encampment of folks enjoying the river—fishing, swimming, and boating. We waved at one another as our trio shoved off in our two canoes. Naccarato led, and Mark and I followed behind. “I’m trained in wilderness advanced first aid,” our guide said reassuringly. “But we’re a long f—ing way from anywhere, so don’t get hurt.” I could have sworn I heard banjo music, but maybe it was just the wind.

The Temple Canyon run is part of a 191-mile stretch of Rio Grande that holds the federal “Wild and Scenic River” designation, the only portion of the state’s roughly 185,000 miles of rivers so honored. Although often overshadowed by the likes of Santa Elena Canyon, Temple is a beautiful excursion full of natural wonders. Naccarato has recently turned to this trip as a solid two- or three-day option for clients.

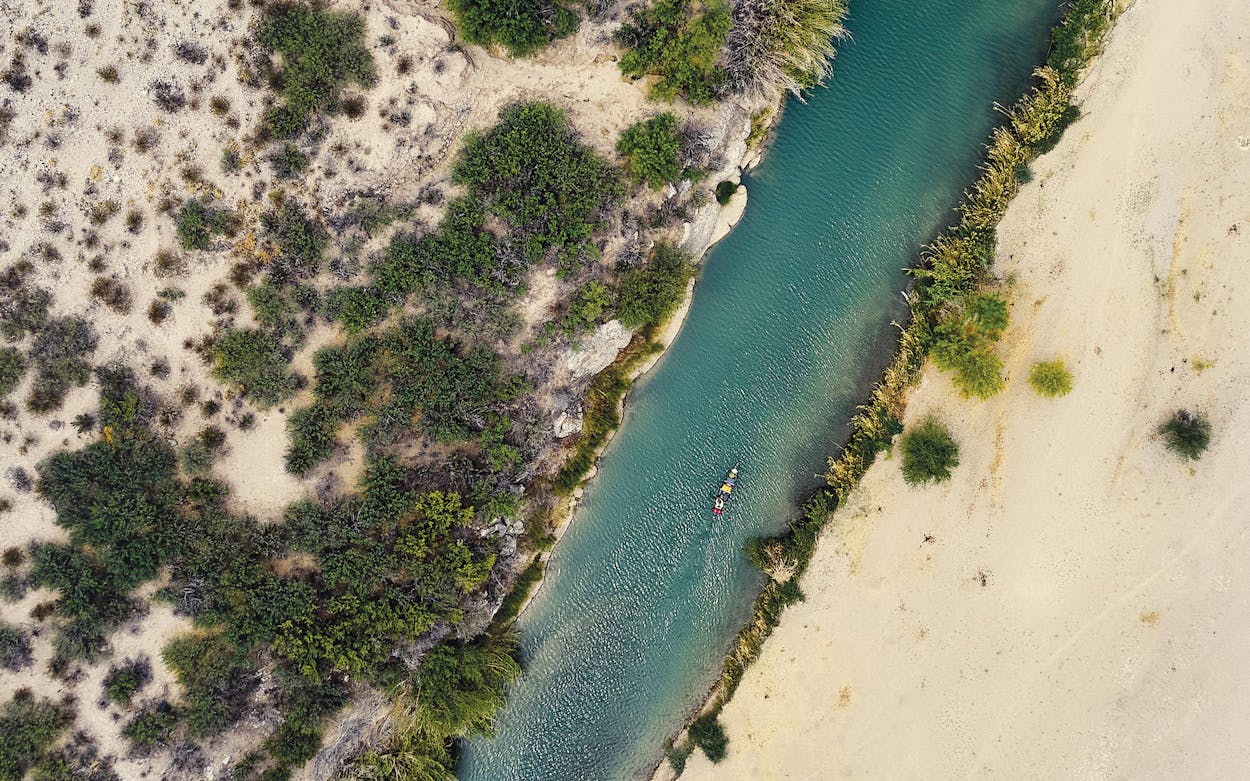

One upside to the current low flows is that the water—where there is water—is much clearer than the Rio Grande’s usual butterscotch brown. This struck me when I first glimpsed the river, before we launched. Against the unending panorama of desert browns, its teal-green hue was welcoming, the water sparkling and refreshingly cool under the rising and warming sun.

Before long, we were making our way through the high walls of Heath Canyon, which brought those long-ago photos vividly to life: the sheer canyons; the craggy, mountainous terrain; the lechuguilla, ocotillo, sotol, yucca, and other Chihuahuan Desert flora. It was all there, unchanged.

Soon we were meandering through Horse Canyon. Along both banks, we spotted occasional signs of feral horses and burros. Every so often, we’d hear loud braying. Naccarato told us that burros had come right up to him at campsites. He wasn’t sure if they were just curious or had become accustomed to snacks from river campers.

The pace was unhurried and relaxing. After a couple hours more of paddling and floating and gawking at the beauty, we stopped for a rest and some lunch. Naccarato unpacked a small kitchen and set out an impressive spread that included hummus and crackers, olives, a charcuterie-and-cheese board, sandwich fixin’s, and tangerines.

With his impressive lamb chop sideburns and an array of wildly varied tattoos (including the Major League Baseball logo on his thigh and the name “Taylor Swift” in script over his heart), Naccarato, who played drums in Austin bands in his younger years, looks the part of a river guide. He also boasts extensive back-of-house restaurant experience and honed his cooking skills when he co-owned a food trailer that specialized in cheeseburgers and veggie burgers.

In 2018 he combined his canoeing and culinary talents for none other than Anthony Bourdain, whom Naccarato accompanied on a trip with his previous employer through Santa Elena Canyon just months before the celebrated chef’s death. “Thank you for showing me this ludicrously amazing place,” Bourdain would tell his guides on one of the final episodes of his popular television show, Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown.

As we proceeded, a slight headwind greeted us. Before long, we paddled through Driftwood Canyon, where a strong gust sent a blinding but blessedly brief sandstorm across the river from the Mexican side. Such is paddling when you’re paddling through the desert. Aside from that short-lived squall, the wind wasn’t ever much of an issue. So untaxing was the physicality, in fact, that I’d occasionally catch Mark sitting for lengthy stretches with his paddle across his lap, hands clasped behind his head, appearing gobsmacked by the scenery. “Hey, Cleopatra,” I barked at one point, when I felt that the meditative trance had gone on long enough. “This barge ain’t gonna power itself. Let’s get that paddle wet, huh!”

By mid-afternoon we’d reached the area for which our run was named: Temple Canyon, so anointed by Robert T. Hill, the father of Texas geology, on his 1899 expedition down the Rio Grande. The limestone formation on the Mexican side resembles, with a little imagination, a temple of some sort perched atop the cliffs above. We found a sandbar directly beneath it and set up camp there. It was perfect: beautiful, well shaded by the tall cliff on the U.S. side with water deep enough for a refreshing dip. Firewood was plentiful, though we kept our camp blaze small and contained inside an old refrigerator drawer Naccarato uses to minimize the risk of sparks igniting the drought-ravaged brush around us (and for easy cleanup).

We were inside the Black Gap Wildlife Management Area, home to one of the state’s successful desert bighorn sheep restoration projects. We spied some tracks, but Naccarato suspected they belonged to aoudads, ruminants that were brought from North Africa to zoos and exotic-game ranches in Texas and let loose to flourish in the wild. Naccarato told of seeing them easily scale sheer cliffs. He also mentioned that when climbing, they’ll sometimes trigger a rockslide. I looked straight up, then at the scattered rocks around us, and scratched my chin. Naccarato mentioned that a friend of his had once narrowly escaped such a slide. I looked up again.

Soon, with a cold beer in hand, I had moved on from dark thoughts of being pummeled to death by falling boulders. The camping conditions were ideal, the setting was postcard perfect, and the company was good. Naccarato had set up a latrine, started a fire, and begun prepping dinner. The night’s menu would include grilled ribeye with spicy chimichurri sauce (which he prepared on the spot), mushrooms, potatoes accented with sprigs of charred rosemary, and grilled asparagus zested with fire-roasted lemon. It was delicious.

As the sun set in the west, it majestically lit up the temple. We sat beneath it around the fire on the riverbank, soaking it in, sipping tequila, and talking. This trip had really shaped up, I thought. I was happy that I hadn’t been deterred by the dire reports I’d received when I made those initial calls. Eventually, we lay our heads down on our pillows beneath a clear sky (no tent required) and a bright gibbous moon that left the canyon well illuminated. I never even unpacked a flashlight. But for braying burros off in the distance, the night was quiet. No rocks fell on us, and there weren’t even any bugs to speak of. Out here in the middle of nowhere, under the temple on this beautiful night, I counted myself blessed.

The next morning, in the depths of the canyon, the unrelenting desert sun never blasted us directly. The air was cool but not cold, and before I was out of my sleeping bag, I’d heard Naccarato rekindling the fire and preparing breakfast: cowboy coffee, eggs scrambled with potatoes and onion and cheese, crispy bacon, warm tortillas, sliced mango, and tangerines. After breakfast a wild turkey gobbled a greeting from across the river. I took an eye-opening dip in the chilly water and then packed up. We launched the canoes for a three-hour paddle past Bourland Canyon to our rendezvous with Naccarato’s shuttle driver at the Maravillas Creek take-out.

The conditions were again ideal, and the going was easy. We spotted a few of the turtles known as Big Bend sliders, heard more burros, and encountered nary another human.

Soon, we’d loaded up and enjoyed a lunch of cheese, charcuterie, sandwiches, and fruit at the tailgate of the truck. And then we were rumbling up the rough gravel road out of Black Gap and back to where we’d put in. The trip was only about twenty miles, but it took a solid hour because of the rough terrain. Back in Marathon, we thanked Naccarato for a splendid trip and said our farewells. We checked into the luxurious Gage Hotel and headed for its swimming pool and then its White Buffalo Bar. We’d return to Austin the following day, but the trip, of course, has stayed in my thoughts.

The seeds that were planted in my boyhood by those timeless photographs of faraway West Texas in the halls of my dad’s law firm had been lying dormant for decades. Now they’ve finally germinated. I’m as certain that I’ll be back for future river trips to other parts of the Big Bend area as I am hopeful that the unrelenting drought will finally release its stranglehold and that there will once again be water to paddle on the beautiful Rio Grande. Who cares if it’s muddy?

This article originally appeared in the July 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “A Grande Adventure.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Big Bend