On a brisk morning in October, the guttural calls of camels pierced the air as campers unzipped their tents and stepped out of their RVs to overlook thirteen hundred acres of sprawling Hill Country ranchland. Sunlight filtered through the mesquite and oak trees on Muleshoe Farm and Ranch in Comfort, about 45 minutes northwest of San Antonio, as attendees made their way to the campfire for coffee and their first lesson. For four days and three nights, the thirteenth annual Southwest Camel Conference would transform the ranch into a vast outdoor classroom for cameleers and their humpbacked charges.

Diane Pennock Small and her fourteen-year-old mentee Landry Simon drove nearly a thousand miles from their home in Berthoud, Colorado, for the event. They had one major goal in mind: to learn to saddle up and finally ride their five-year-old camel, Humphrey. “We’ve had a rough start with him,” said Pennock Small. The agitated camel had at times been unruly—at one point breaking his halter and forcing his owners to chase him for miles. Four hours after his escape, Pennock Small and Simon returned home with Humphrey, but “it took months to get back in the pen with him,” Pennock Small said.

With more than a dozen camels in tow, roughly fifty camel enthusiasts, experts, and trainers from across the country flocked to the Muleshoe Farm and Ranch for the camel conference. Idaho couple Lisa Berry and Darren Bell wanted to see their mammoth but mild two-humped Bactrian camel, Sampson, face his fears and finally cross water. D’Yan Gay, a 40-year-old San Antonio mom, wanted her young, energetic camel, Merlin, to be trained and safer around her thirteen children. And California resident Chad Dunivan, 48, whose camels and livestock died after he evacuated them during a wildfire last summer, was simply there to help out and enjoy the camaraderie.

The group watched presentations on camel poop, parasites, and nutrition; took part in a demonstration on how to train camels to “kush,” or lie down on command; and learned from exercises in hobbling, the process of tying the camel’s knees or ankles to get a more consistent stroll. Some of the programming was not for the squeamish. There was a live castration performed by Utah-based veterinarian and trainer Charmian Wright, and a saddling demonstration, during which a displeased camel roared a throaty growl and spewed slimy green goo onto trainer Sidi Amar Taoua’s shirt.

Taoua, who grew up with camels in the Sahara Desert in northern Niger, was unfazed. “That’s just baby talk,” he said, holding tight to the reins. For his tribe, the Tuareg, camels are a way of life. “We use them for everything,” Taoua said. “To go to the market, to go to school, to go get water. . . . To us, they are a part of our tribe. They are sustainable creatures.” Now living in Las Vegas, Taoua works as a professional exotic-animal trainer.

At the conference, he spent time with Michael “M.J.” Roberts, 35. Roberts, one of the only African American cameleers in the country, attended with his seven-foot-tall camel, Tazah, who has gone viral for his appearances around the Dallas area. The gentle giant draws crowds at nightclubs, trail rides, car washes, and even a Wendy’s drive-through. “It catches a lot of people’s attention. We’ll be riding down the street and he’ll just be looking around,” said Roberts, who often tows Tazah in a black, open-top trailer.

Roberts and Tazah joined their friends on the conference’s treks through the Hill Country, with each camel mounted or led for up to five miles a day. “It’s honestly the most real-world teaching situation for a camel or a handler, to get out on the trail and go,” said conference organizer and camel historian Doug Baum. Based in the Waco area, Baum, who owns ten camels of his own, leads annual treks through Big Bend National Park and international camel tours in Egypt, Morocco, India, Kenya, and Jordan.

While camel owners might seem rare, “we’re everywhere,” said Baum, 53, “but there’s no real clearinghouse of knowledge or information.” To fill that gap, the former zookeeper has worked since 2008 to build a tight-knit network of camel connoisseurs through the conference, which evolved from a similar gathering launched in Missouri in the 1990s, Baum said. Today, the Southwest Camel Conference and Training Clinic bills itself as the longest-running camel event in North America. Among the group this year were heavy hitters within the camel industry, including several mobile exotic-animal handlers and camp chef Gil Tafolla Hernandez, whose great-great-grandfather handled camels while serving in the U.S. Army in the 1800s. Bill Rivers, trainer and owner of Movieland Animals and Camel Farm in Pipe Creek, a company known for providing trained exotic animals for TV shows and films, also made an appearance.

“To have them in one place, it’s incredible,” said Kristin Fraihzo, a Michigan resident who purchased her first camel, Bruce Almighty, in July.

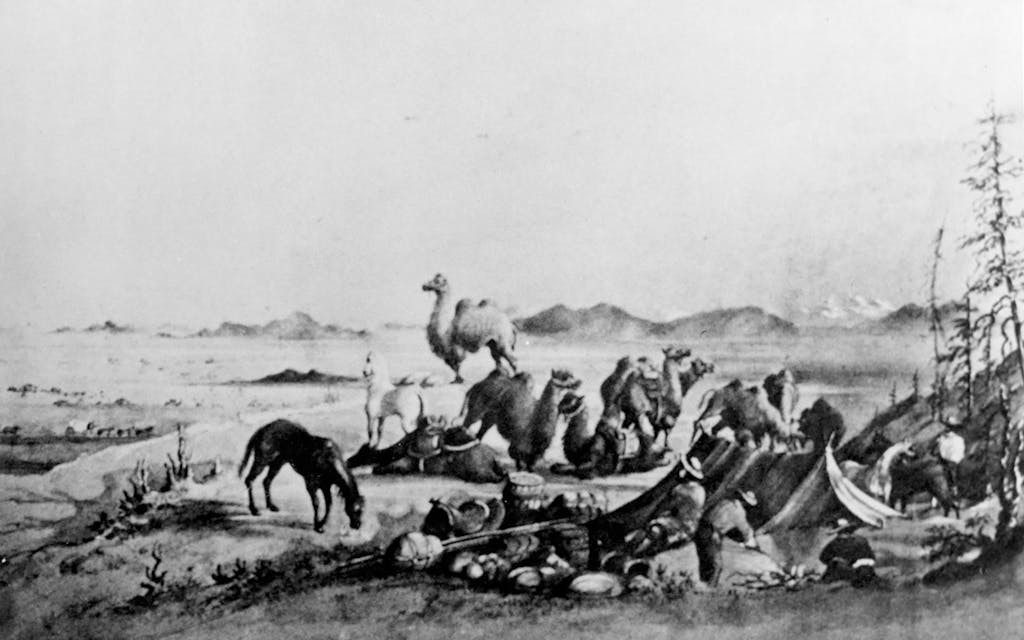

If Texas camel culture sounds like a new fad, that isn’t exactly true. Just eighteen miles from the conference is Camp Verde, the former home of the U.S. Army Camel Corps. In 1855, at then Secretary of War Jefferson Davis’s urging, Congress spent $30,000—nearly $1 million in today’s dollars—on the project, which sought to see if camels were fit for military use. Thirty-odd camels were taken from North Africa and brought ashore at Indianola, along Matagorda Bay, in 1856. By 1857, the Army had imported a total of around 75 camels from Tunisia, Egypt, and Turkey. The thinking went like this: the West was rugged, hot, and dry; soldiers there had to travel many miles in harsh conditions, without much water or rest. Wouldn’t that make Texas the perfect environment for dromedaries?

On one level, it did. The animals thrived, carrying seven-hundred-pound packs without complaint and covering as many as one hundred miles in 24 hours. But some historical accounts note that the camels didn’t get along with their human handlers or other animals on the trail. The creatures spooked skittish horses and mules and had an unpleasant smell; soldiers struggled to groom them and keep them healthy. “The camels’ ability to defecate without any warning whatsoever to anyone standing to their rear quickly overrode whatever lovable or useful qualities they may have possessed,” writes John Shapard in a Military Review article. (For his part, Baum argues that these accounts were exaggerated, and points out that most animals defecate without warning).

The military still got good use out of the camels. Two surveying expeditions, in 1857 and 1858, used them to help establish a wagon road through Arizona and California (parts of which are now U.S. Route 66). Within Texas, the camels helped find locations for forts and survey practical routes to the border. But the experiment didn’t last long, with the Civil War putting an end to the venture. The Confederate Army captured Camp Verde in February 1861, and for a time the camels hauled cotton and salt between San Antonio and Brownsville. Most were eventually put up for auction or abandoned; some ended up in traveling circuses.

More than a century and a half after the Camel Corps experiment, are Americans ready to give camels another chance? Baum estimates that the U.S. now has around five thousand camels, most of which were imported from overseas and are owned by private individuals. There’s been some progress, but “we don’t as a nation recognize their utility,” said Jim Jensen, a retired veterinarian and camel expert who presented at the conference. “They’ve been used in so many countries for agriculture, transport, dairy, and meat. There are many societies of people who have lived on the camel.”

Aside from being able to travel long distances and survive more than a week without food or water, camels, which can live for about forty years, can also handle warmer climates—a plus considering climate change, said Terri Bowen Lindley, 59, an exotic-animal trainer based in Oklahoma City. Their hair, typically finer than sheep’s wool, can be spun into sweaters, scarves, and hats. Some societies eat camel meat, and the animals’ nutrient-rich milk is a sizable commodity. According to a report from Global Industry Analysts, the U.S. market for camel-milk products is worth $3.1 billion in 2021, and it’s expected to grow. The study predicts that the global market for camel milk will surpass $14 billion by 2026.

“If this country was to go dark,” with no internet or electricity, these are the animals people would want by their sides, said Lindley. “They fit every need. There are so many things they can do.” And unlike horses, they’ll eat almost anything, have minimal grooming needs, and don’t wear shoes.

But camels, which range from 1,300 to 2,000 pounds depending on the species, can pose a safety risk if not trained properly, Lindley said. They’re also an investment in more ways than one. A typical camel sells for about $6,000 to $18,000 depending on sex, age, species, and training. Then there’s the cost of keeping them healthy. Because camels are hypersensitive to parasites, some owners test their animals’ fecal matter at least once a month, for example. And, at least in the U.S., very few veterinarians are trained in camel health.

The conference and its network are attempting to change that. Veterinarians and technicians drew blood from camels at the conference to assist a Michigan State University team in its efforts to create a DNA database for camels around the world. The North American Camel Ranch Owners Association, launched last year, announced its goals to build a registry that could help camel owners learn about their animals’ ancestry and potential breeding issues. And though the pandemic has slowed some of its efforts, association secretary Valeri Crenshaw said the group, which helped sponsor the camel conference, is also advocating for the U.S. Department of Agriculture to classify camels as livestock rather than exotic animals. This designation could help make camel health and science research more mainstream.

Longtime exotic-animal veterinarian Alice Blue-McLendon, who directs Texas A&M University’s Winnie Carter Wildlife Center, is also working to prepare the next generation of veterinarians to handle camels. In July, the center received two camels, one of which was diagnosed and treated for fibrous osteodystrophy, a common metabolic bone disease that can result in fibrous connective tissue replacing the bones. A group of about eighty veterinary students will have the chance to interact with the camels daily.

By the final day of the Southwest Camel Conference, most of the cameleers were beaming with pride. Sampson had finally crossed water. Dunivan, the Californian whose camel had died after the wildfires, was elated when his wife surprised him with the gift of a new animal. Merlin, the rowdy camel from San Antonio, had made some progress and undergone a castration that would mellow his spirit. And after some work with trainer Taoua, Pennock Small and Simon were able to ride Humphrey for the first time. “It’s a dream come true,” Simon said. “I didn’t think there’d ever be a day.”

Seeing such an interest and investment in the camels was particularly heartwarming for Taoua, who said the event reminded him of his community in Niger and felt like a “home away from home.”

“It’s rare and unusual to find people who love camels like I do, especially in the modern United States,” Taoua said. “I’ve found my tribe.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Critters

- Hill Country