This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

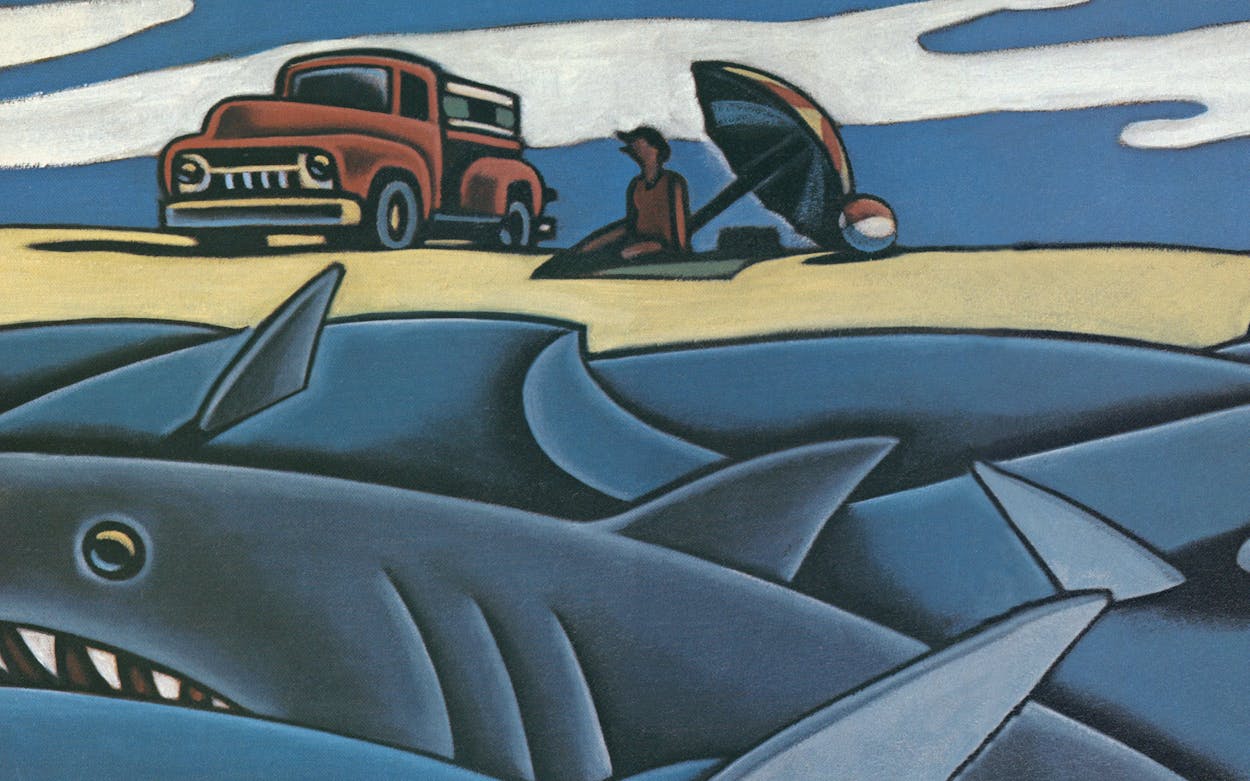

In 1962 a surf fisherman carrying a stringer of fish around his waist was severely bitten by a shark and bled to death near South Padre Island. That tragedy is the only confirmed shark-related fatality in Texas history. The last shark attack of any kind in Texas waters occurred three years ago, even with hundreds of thousands of sharks and hundreds of thousands of bathers, surfers, and fishermen all sharing the same water. That is, it was the last attack until this summer.

As of July there had been three incidents involving sharks and people—all women—within ten miles of Port Aransas. The first attack, on April 18, Easter Saturday, was the worst. A sixteen-year-old Kingsland girl named April Voglino was swimming in chest-deep water fifty to one hundred feet from shore just north of Mustang Island State Park. Her father, Robert, heard her scream and saw a five-foot gray shark ripping into April’s right arm. He grabbed the animal by its dorsal fin and hit it repeatedly. Twice he chased it away, only to have it circle back. When the girl reached land, her mother, Beth, used her hands to stop the profuse bleeding. April lost her arm above the elbow, but her parents’ quick actions saved her life.

It was a one-in-a-million freak accident, experts and authorities agreed, just another example of the unpredictable nature of sharks. Then on Sunday, July 12, during a busy tourist weekend, two more shark attacks were reported within half a mile of each other on the Port Aransas beach. At two-thirty sixteen-year-old Brenda King of Rockport was cavorting in four feet of water some 25 yards offshore. She had just handed her five-year-old niece to her aunt when something large and gray emerged from a breaking wave and knocked her down. As she struggled to get up, that same something swam underneath her and bit her on the right foot, causing several small puncture marks and leaving on her ankle a gash that required ten stitches. King is convinced that the something was a shark.

There was no doubt about what sank its teeth into Carol “Kitt” Viau’s leg four and a half hours later. The 32-year-old Port aransas resident had been bodysurfing when her left foot bumped into a large object. She pulled her leg out of the water and saw a four- to five-foot-long shark trying to swallow her foot. While she punched the creature, two other swimmers pulled her to safety. Viau suffered five-inch lacerations.

Suddenly Port Aransas was the shark capital of Texas. City and county officials responded by stepping up land and air patrols along the coastline, but if there was a killer running amok in the briny deep, it didn’t show itself again. The only feeding frenzy was that of the flock of helicopters, cars, and vans carrying reporters who descended on the town in search of a juicy story.

As surfboard and float rentals plummeted and shark-fishing excursions ran at capacity, everybody had a theory on what caused the attacks. Captain Paul Dirk, who has probably caught more sharks off the Texas coast in his career than any other fisherman, cited a migration of sharks into the area. He said the influx may have been caused by the recent red tide, which had killed a significant number of mullet and other bait fish that sharks dine on. He also reckoned that it was a miracle more people hadn’t run into sharks and vice versa.

At the University of Texas Marine Science Institute in Port Aransas, director Robert Jones conferred with colleague H. Dickson Hoese, a biology professor at the University of Southwestern Louisiana and a coauthor of Fishes of the Gulf. Studying photographs of Brenda King’s bites, they wondered whether the villain was a shark or a ray. “She said the attacker was rough and slimy. A ray is both,” Jones said, but a shark’s rough skin brushing against a bathing suit underwater could feel slimy too. The experts also speculated that heavy summer rains inland had clouded up the already murky water, possibly causing sharks to mistake flashing palms and soles of feet for mullet. Or perhaps the swimmers had wandered into a surf zone that was full of juvenile sharks.

Hoese wondered whether the temporary ban on inshore shrimping, which meant a reduced supply of trash fish discarded from shrimp boats, may have made the sharks ravenous. A rumor floating around town was that the victims may have been having their menstrual periods when attacked (it has been confirmed that two of the women were not). A shark can detect even a trace of blood, but Hoese pointed out that more than 90 percent of shark-attack victims are men.

By process of elimination, Jones and Hoese narrowed the likely July provocateurs to members of the voracious Carcharhinidae family, which includes bull, Atlantic sharp-nosed, and blacktip sharks. Their one certain conclusion would disappoint Jaws fans. Said Jones, “This is definitely not a rogue shark running up and down the beach biting young women.”

As Labor Day neared, surfers and waders had returned, and fears had subsided. The Gulf, Port Aransas’ lifeblood, was gentle and benign. But Captain Paul Dirk looked out toward the water with wariness. “Once you get out past that second sandbar,” he said, “there’s more of them out there than there are of you.”

- More About:

- Critters

- TM Classics

- Port Aransas