This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

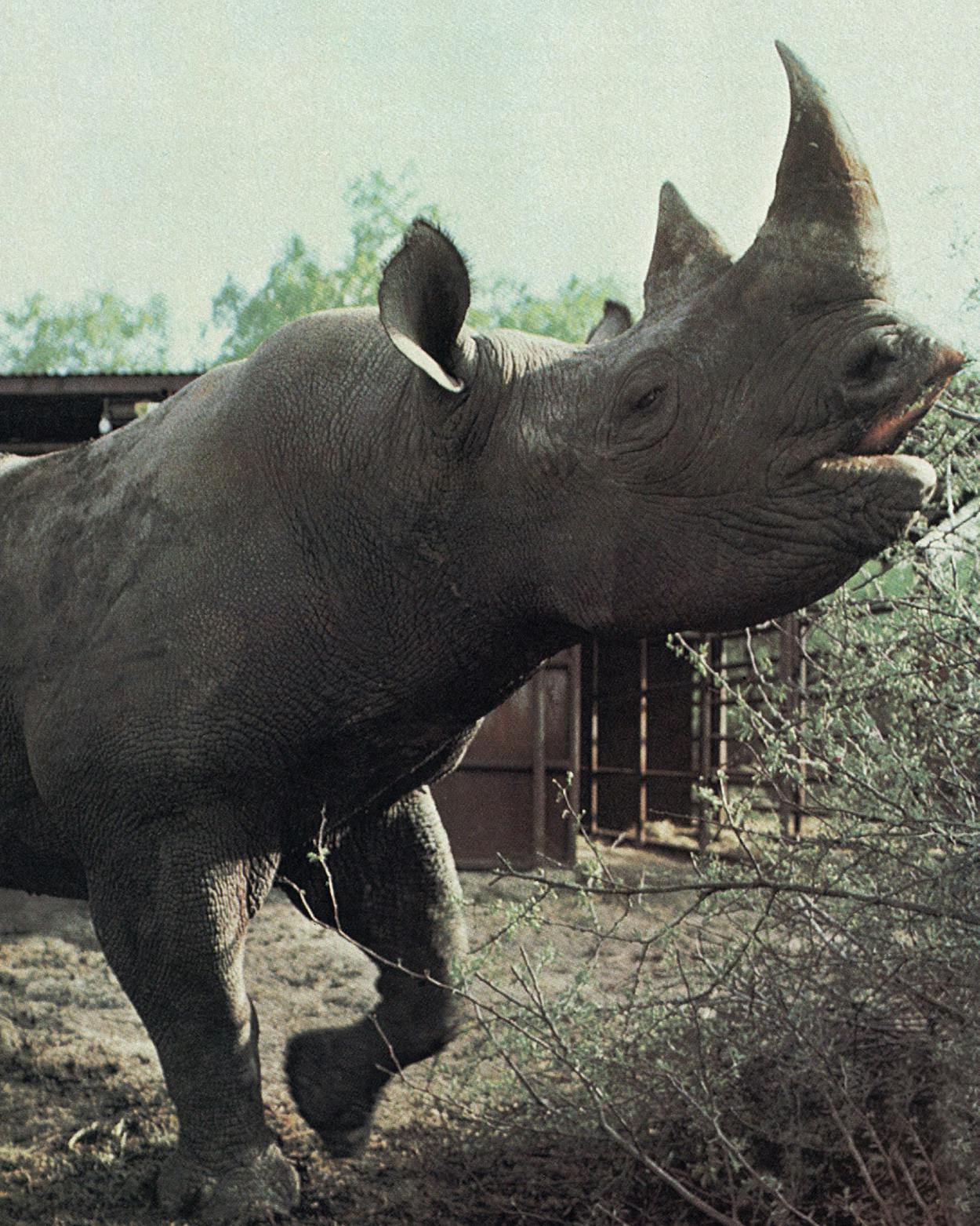

Camouflaged by the spotty shade and dusty chaparral, the black rhino lies with her massive jaw against the ground, flicking her fringed ears at the nagging flies in her one-acre pen in the Rio Grande Valley. Suddenly she hears or smells something she doesn’t like. She comes to her feet in stages, using her front knees for support. She stands there droop-bellied, about as tall and broad as a Santa Gertrudis bull.

Her skin is a gray, wrinkled, baggy fit, and her short legs are as sturdy and big around as fire hydrants. The fearsome part of her anatomy begins with a neck of astounding bulk and muscularity, yet the lines that flow into the two horns on her nose have an alluring symmetry and grace. Set below the shorter horn, her dark, piggish eyes are enclosed by puffy and deeply wrinkled bags of skin. She strains with obvious difficulty to see, then snorts and bursts forward with tremendous speed and agility. Sapling mesquites crack and flatten beneath the force of her charge. She gallops with a smooth roll of her shoulders and carries the business end of her nose low to the ground.

“The Best People I Know”

Near downtown McAllen, remote-control gates swung open to admit the cars of guests arriving at a dinner party that Calvin and Marge Bentsen were giving to celebrate the arrival of rhinos in Texas. During the three months the rhinos had been in the state, they had sent tremors through the rarefied worlds of big-game hunters and wildlife conservationists, creating a near-scandal that had rocked bureaucracies all the way to Washington. But this was a party, and on this particular night the rhinos were the symbolic guests of honor.

Within the compound, which covered a city block, the vehicles followed a circular drive past palms and willows toward a sprawling, one-story Spanish Colonial mansion. Around the side of the mansion, smoke billowed from a large barbecue pit. It was a warm May night, and the party’s host, Calvin Bentsen, had sweated the back of his long-sleeved khaki shirt from his belt to his epaulets. Though several young Mexican American men in white servant’s tunics moved around inside the mansion, taking shawls and carrying trays of drinks, Calvin trusted the cooking of his marinated fajitas to no one but himself. Squinting through the smoke at the brisket strips, he raised and poked them gingerly with a long-handled fork.

A tall, handsome, freckled man with sandy hair and an endearing gap between his front teeth, Calvin was a McAllen banker and a nephew of U.S. senator Lloyd Bentsen, and he had recently committed himself to breeding rhinos. Under the auspices of Game Conservation International (Game Coin), a small group of hunters and conservationists had managed to cut through scads of red tape and transport five endangered black rhinos halfway around the world. Calvin’s guests had all participated in the half-million-dollar project, but Calvin was the member who had volunteered for the headache and responsibility of keeping the rhinos on his La Coma ranch.

The guest list included Martin Anderson, an urbane Honolulu and San Francisco lawyer who owned a 1.5-million-acre ranch in Kenya, and Alejandro Garza Laguera, the scion of a wealthy industrialist clan in Monterrey, Mexico. The party was dominated, however, by Texas oilmen and ranchers dressed in safari attire. They had flown to the Valley, many in their own private jets, to toast their newfound success and celebrity as conservationists, but as the organization’s name implied, their first interest was game, not wildlife. Game Coin treasurer Ed Wroe, a squat, gravel-voiced Austin banker, had told me, “You’ll notice most of these people are hard of hearing in one ear. Which ear depends on whether they shoot right- or left-handed. All that heavy artillery takes its toll.”

Calvin’s wife greeted the guests at a set of front doors that were half as wide as most living rooms. Marge Bentsen was pretty and petite, though her blond coiffure added three or four inches to her height. She wore an off-white, high-waisted, floor-length dress with puffed sleeves.

A long central hall, paved with Saltillo tile, led toward distant wings of bedrooms. The sitting room that faced the foyer had a plush sofa, Victorian chairs, and a glass-walled view of landscaped grounds. There were ebony sculptures and paintings with African themes, but my primary impression on entering the house was that I had never seen so many dead animals in all my life. Horns, antlers, tusks, hides—all were artfully blended into the mansion’s decor. Marge delivered us to the young man who was to take our drink orders, then she returned to the dining room and resumed wrapping silverware in white linen napkins, which she then slipped into ivory napkin rings and inserted in the slots of a white ceramic rhinoceros. The centerpiece of the forthcoming buffet was a hollowed-out watermelon that some enterprising soul, with the help of a couple of strategically placed green bananas, had turned into yet another likeness of a rhino.

Rhinos—when they finally mate—make up for their solitary ways, years of celibacy, and stormy courtships.

In a kitchen anteroom at the end of the hall, where the barman was mixing frozen margaritas, one of the guests spoke deferentially to Harry Tennison, the president and board chairman of Game Coin, who from time to time turned away from the bar and raised a finger to his right ear, as if he was having trouble hearing. In his mid-sixties, Harry was the kind of happy old-timer that we all aspire to be. A retired Coca-Cola magnate living in Fort Worth, he had passed wealth on to his children and grandchildren and had freed himself to do anything he wanted. With ruddy, lightly veined cheeks and eyes that positively jitterbugged, he wore a loose-pocketed safari jacket and a string tie over his khaki shirt. The tie’s draw piece was a miniature head of a bighorn sheep, cast in gold.

When the barman behind him hit the switch of an electric blender, Harry abruptly danced on his toes and jerked a minute hearing aid from his left ear. “Godamighty!” he cried in response to the blender’s shrill whine. “You think that doesn’t ring my chime?”

What Harry wanted to do most these days was to hunt birds and fish for salmon, but in his day as a big-game hunter, he had contributed trophies to the walls of Indian maharajas and African heads of state. He dropped names such as “my good friend Prince Philip.” On a recent tour of England, his Game Coin colleagues had mentioned the desirability of having an audience with the queen. Their British host doubted that that was quite possible, but Prince Philip showed up shortly afterward, shaking hands and saying howdy.

Harry prided himself on his ability to get things done, and from the start he had looked upon the black rhino project as his private dream and mission. He foresaw the day when perhaps a hundred black rhinos might be scattered on ranches throughout the American Southwest. Coordinating their program with those of the nation’s zoos, the rhino breeders would swap bulls and pamper the pregnant cows in the manner of livestock. In time some of the offspring might even be returned to the South African bush.

Significantly, Game Coin pulled off the importation of the rhinos without help from environmental groups such as the Sierra Club. Harry had nothing but contempt for them; he called them tree huggers. He borrowed his conservationist approach from Aldo Leopold, Theodore Roosevelt, and European dukes, barons, and lords.

Harry and I carried our drinks through another sitting room, with walls of jungle-green, where we lifted our glasses and extended our stride to avoid stepping on the zebra-skin rugs—tails and manes intact—that were strewn across the tile floor. (One does not walk on another’s trophies.) At the end of the room, glass doors framed by matched elephant tusks opened onto a patio.

“I have hunted all over the world,” Harry said, savoring his good fortune. “I’ve hunted on the backs of camels, on the backs of elephants. Have you ever ridden an elephant? Darn things will beat you to death. Bounce you till your teeth fall out. Elephants have the clumsiest natural gait on earth—three feet down while one foot is moving. They have no rhythm in their souls.”

“What prey,” I asked, “is, ah, bad enough that you need to be on top of an elephant?”

“Tigers!” Harry cried with an ecstatic blaze of those kindly eyes. Just as quickly, his eyes clouded with concern for the potential misunderstanding. “But it was legal then, you see.”

We crossed the patio to a ground-level wine cellar that was as large as a corporate boardroom. Its chandelier was constructed from antlers. Finished with his barbecuing, Calvin joined a small group of friends gathered there. He chatted with Jean Waggoner of Fort Worth, an heiress to the historic cattle ranch in North Texas. With short hair tinted blond, animated brows, and a regal way of carrying her head that accentuated the line of her throat, she probably intimidated women half her age. An avid hunter who had done most of her tracking on this continent, she wore a Mexican sundress with belt and bracelets of finely crafted Indian silver.

Calvin rested a large hand on Harry’s shoulder. “I’ve gone on six African safaris,” said Calvin. “Brag on yourself, Harry. How many times have you been over there?”

“Thirty-four,” said the older man, grinning fiercely.

Forsaking the racked bottles in view, Calvin opened a cabinet and brought out a liter of white wine. He brandished it proudly. Cries of enthusiasm greeted the label, Zonnebloem Premier Grand Crû.

“Wherever did you find it?” asked Jean. “I’ve looked all over Fort Worth.”

Calvin winked at her and filled all the glasses around. “I now buy it by the case,” he said. Bottled in the Republic of South Africa, which is better known for apartheid than for its vineyards, the wine was crackling dry and very good.

Harry quaffed his wine and immediately poured himself another glass. “God, I love this stuff.”

We walked away from the others and took a seat on a small sofa. His eyes dewed with sentiment as he looked upon his friends. With an expansive wave of Calvin’s crystal goblet, he said, “These are the very best people I know.”

The Rhino Mystique

Harry and his friends represent one endangered species, the big-game hunter, trying to save another—the black rhinoceros. That might seem odd, but rhinos have always had a profound effect on the human imagination. Rhinos walked the earth not only after dinosaurs died out. Other mammals of that era, such as mastodons and saber-toothed tigers, succeeded the great reptiles in extinction, but rhinos have survived 60 million years.

One of the first records of man’s fascination with rhinos is a European woodcut, carved in Augsburg in 1515, that features a small spiral horn on the hump of a rhino’s neck, reflecting an ancient belief that rhinos have some connection with the mythical unicorn. A more persistent belief—that powdered rhino horn is an aphrodisiac—is thought to have originated in India, whose traders controlled exports from East Africa. Peddling the dual horns of Africa’s rhinos, the Indians probably added that selling point to a long list already drawn up by the Chinese and Southeast Asians.

Irrational belief in the magic of rhino horns has not been limited to unwashed peasants. Chinese emperors customarily received a cup or bowl elaborately carved from rhino horns on each of their birthdays; the scenes on those vessels depicted Taoist visions of immortality. Chinese and Southeast Asian physicians and pharmacologists have traditionally prescribed shavings of rhino horn for a range of ailments that includes snakebite, hallucinations, typhoid, carbuncles, high fever, night blindness, and general lethargy (use by pregnant women not recommended). Today, the use of rhino horn as an aphrodisiac is largely confined to the Indian city of Bombay and the northwestern province of Gujarat. Rhino horn is expensive, and other animal products such as monkey glands and goat bile are offered as substitutes. The Indian government has cracked down on the trade to protect its own rhino population, but pharmacists in Singapore still carve shavings from rhino horns and sell them by the gram as nonprescription medicines. In Peking the influence of Chairman Mao, who boosted the integration of traditional Chinese medicine with modern Western practice, has contributed heavily to the rhino’s demise.

Still, the largest single exploiter today is North Yemen, a tiny country on the lower end of the Arabian peninsula, across the Red Sea from Ethiopia. Men there desire rhino horn handles on the daggers they start wearing in their belts at the age of twelve. Fifty thousand North Yemeni lads come of knife-carrying age every year, and rhino horn daggers in that country’s shops bring from $500 to $12,000. Smugglers of rhino horn sail dhows out of East African ports on the Indian Ocean. Their supplies come from poachers who shoot the nearsighted rhinos repeatedly with small-caliber rifles and shotguns and wait for them to bleed to death. Then they saw off the horns and leave the carcasses to rot.

The poachers are often impoverished and take advantage of the political instability of the region. When Idi Amin’s Ugandan soldiers fled from Tanzanian invaders in 1979, they ransacked their own country’s game preserves, collecting rhino horns and elephant tusks to sell in exile; meanwhile, the Tanzanians machine-gunned hippos for meat and simply for the hell of it. Wildlife conservationists estimate that the world rhino population declined by half during the seventies, and the decade’s toll on black rhinos may have been as high as 90 per cent.

A Matter of Style

After opening several bottles of Zonnebloem Premier Grand Crû, Calvin led us out of the wine cellar, back across the patio, through the door framed by the elephant tusks, and into the den, where everyone was trying to keep from standing on the zebra-skin rugs. Sometimes the person who is not invited to a party says as much about the gathering as the guests who are. Noteworthy by his absence here was Texas’ other breeder of black rhinos, a 38-year-old natural gas entrepreneur named Tom Mantzel. Tall and personable, Tom had helped engineer the movement among American zoologists to sanction breeding of endangered wildlife on private ranches. His 1500-acre retreat southwest of Fort Worth near Glen Rose was stocked with exotics that included sable antelope, wildebeests, European red stags, giraffes, Saharan addax antelope, and Grévy’s zebras. A shipment of cheetahs would soon be on the way.

Tom’s involvement with black rhinos began in late 1981, when he attended a posh New York fundraiser for endangered wildlife. With the help of Industrial Vehicles Corporation (IVECO), an Italian truck company eager for publicity in America, and the African Fund for Endangered Wildlife, Tom raised enough money to import his own rhinos. But his wildlife sources were in Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia). When his project fell victim to that country’s internal politics, he realized he could get the rhinos only through Game Coin. Harry Tennison, because of his hunting connections, was able to get black rhinos from a state parks board in the Republic of South Africa, but his fundraising efforts had come up short. In August 1983 Tom approached the Game Coin board, proposing a marriage of convenience. Harry was out of the country when the contract was signed, and he went through the roof when he found out about it. He didn’t want to share his precious rhinos with anybody.

But the shaky marriage survived, and in March 1984 five crated, sedated rhinos boarded a 747 freighter. Their South African handler carried a gun loaded with a lethal dart; if one of those crates came apart, an angry and desperate rhino was capable of taking the jumbo jet down. The rhinos shivered overnight in New York City, boarded another flight to Houston, then were split up and trucked to the two ranches. The crated rhinos were lowered into their pens by crane and then released. While TV cameras rolled, they whirled, snorted, threw up dust, charged every sight and sound. Their collisions with the steel fence sounded like car wrecks.

Tom Mantzel and Calvin Bentsen got along fine, but relations between Tom and Harry were slow to warm up. Their chronic disagreement had elements of the tension between Fort Worth’s old and new guards, and it was also a matter of style. The fundamental difference in their outlooks was reflected in the way they reacted to the rhinos. To Harry, rhinos would always be magnificent dangerous animals, beasts whose ferocity confirmed his view of the world. To Tom and his young wildlife specialists, black rhinos were an endangered species that required protection. They discovered that they could lull the animals at the Glen Rose ranch into a passive state simply by stroking their abdomens.

“I have nothing against hunters,” said Tom the day I visited his ranch. “I used to hunt deer myself. But Harry still talks about the Big Five”—the grand slam of safaris, in which an elephant, a rhino, a Cape buffalo, a lion, and a leopard are collected on a single African trek. “That’s like white rule in Rhodesia. Those days are gone.” Harry, however, got in his own licks. Following the TV and photo coverage of the rhinos’ arrival in the Valley, Tom had to make a painful call to his Italian sponsors. All they had asked was that IVECO vehicles be used for ground shipment, thereby appeasing their board with the promised publicity. IVECO got the international spotlight at Glen Rose, but Harry and Game Coin arranged for a prominent sign on one of their rhinos’ crates, sending a pointed Yankee message around the world: “Transportation by Mack Trucks.”

An Uncontrollable Tick

As we circumnavigated the zebra skins en route to the dining room, Ed Wroe mentioned Boone & Crockett (Daniel and Davy, of course), which is the official record book of American trophy hunters. Harry and Ed spoke euphemistically of “collecting trophies”—not “killing animals.” Africa swarms with all sorts of critters, but one that they didn’t mention this night was ticks. Just a month before the party, the U.S. Department of Agriculture had discovered that Game Coin had imported not only rhinos but harmful parasites as well.

Bureaucracies tend to look askance at the transcontinental shipment of wild animals, particularly when the animals are dangerous. Most private applications die in the maze of regulations, but in this case the Bentsen name couldn’t have hurt, nor could that of Ray Arnett, one of President Reagan’s assistant secretaries of the Interior. Arnett ranked in unpopularity among environmentalists right up there with his former boss James Watt, but Arnett was also a member of Game Coin. With all that pull, Game Coin administrators easily obtained a permit from Interior. Ordinarily, to protect native livestock, the USDA would examine all exotic hooved animals and quarantine them for sixty days in New Jersey, but because rhinos have three toes, Interior was able to wave them through New York on Game Coin’s assurance that the South Africans had taken all the necessary precautions.

It was all whoops and champagne until Calvin’s older rhino cow died two months later. Summoned from the Gladys Porter Zoo in Brownsville, veterinarian Sherri Huntress performed the autopsy. The cow, sixteen or seventeen years old, had died from old age and liver disease, which prompted accusations that the South Africans should never have shipped her at all. But the revelation of that postmortem was Huntress’ discovery of live African Bont ticks on the rhino’s hide. She duly reported it to the Department of Agriculture. Pointing fingers of blame at the Interior Department, USDA officials positively swarmed around the Edinburg and Glen Rose ranches for the next few days.

Huntress disabled Calvin’s surviving rhinos with a heavy tranquilizer so the USDA inspectors could proceed with an inch-by-inch examination. At Tom’s ranch they were astounded that the employees’ trick of stroking the rhinos’ tummies eliminated the need for the dangerous sedation. The head of the USDA crew told Tom that they were concerned about a disease called heartwater, which is carried by the African Bont.

As the story unfolded, the news got worse. African Bont ticks are of the dreaded three-host variety. They might attach themselves to feral hogs, certain birds, or even rabbits, all of which disregard fences. One female African Bont tick might disperse 20,000 eggs in her life cycle, and the specter of an uncontrollable tick was feared in the Rio Grande Valley. The nine counties between Del Rio and Brownsville encompassed the permanently quarantined danger zone of Texas fever, a virulent blood disease carried by ticks and against which American cattle have no immunity. The last major outbreak of Texas fever had devastated the U.S. cattle industry in the late thirties. The government vets found no more live African Bont ticks on either of the Texas ranches, but they placed Calvin’s La Coma under a year-long quarantine, which meant that any animal shipped from the ranch had to enter the trailer soaking wet with tick dip, in the presence of a government official.

To some degree, the ensuing furor in the Valley was a function of timing, following, as it did, the Bentsen family’s importation of some controversial trees. The preceding winter’s severe freeze had killed off many of the stately palms along the Rio Grande, and Calvin’s ninety-year-old grandfather, Lloyd Bentsen, Sr., brought in queen palms from Florida to fill the scenic need. The office of Texas agriculture commissioner Jim Hightower granted the necessary exemption—necessary because the importation of queen palms was prohibited by state law. Horticulturists believed that the trees carried a disease called lethal yellowing and that Florida soil was infested with burrowing nematodes. At the time of Huntress’ discovery and the USDA’s alarmed response, allegations of Bentsen arrogance and political privilege already had Valley nurserymen up in arms. Queen palms and now South African ticks—noblesse oblige.

The Purity of Hunting

The dinner guests plucked their linen-wrapped silverware from the ceramic rhino and passed by the carved-watermelon rhino. Calvin served us personally. Arranging the brisket strips on each plate’s flour tortilla, he said helpfully, “Get you some guacamole there and some of that pico del gallo. There you go, put it right on top of the meat. But watch it, now. It’s hot.” On one of the sitting-room sofas, I balanced the plate on my knees and unfolded my napkin. It was the first time I’d eaten fajitas with a sterling silver fork that weighed two pounds.

Ed Wroe occupied a Victorian chair across the room. He was talking about the thousands of dollars people pay for a native trophy whose antlered points and spread were certified by Boone & Crockett. “It’s outrageous,” said Jean Waggoner, who shared the sofa with me. “People who don’t hunt at all. Interior decorators! I would never have a trophy in my home that I did not kill.” The purity of hunting, they all seemed to agree, was easily despoiled.

In the commanding presence of the older woman, Calvin’s daughter Margo, in her twenties, was a bit subdued. Round-faced and pretty, Margo was married to a Dallas banker. Home for a weekend visit, she had joined the party after putting her infant to bed. She wore pants and a blouse and had tied her dark hair back with a scarf. From another Victorian chair, she put in primly, “I don’t know which I hate the most, the bad shot or the illegal shot.”

Finished serving, Calvin stood in the doorway and suggested that his daughter’s views on marksmanship were not just idle chatter. “On Margo’s first safari,” he bragged, “she downed eleven animals with twelve shots. My other daughter Susan is quite a hunter too. She was on a Dallas talk show not long ago, being interviewed about the rhino situation in Africa. The host asked her if she knew a solution.” Calvin grinned and stuck his hands deep in the pockets of his khaki pants. “She told him, ‘Poach a poacher.’ ”

When the party started to thin out, we moved up toward the front of the house, where, in a small den, there was a glassed-in gun rack containing many of the rifles Calvin had used on safari. On a shelf, sample bullets of those firearms stood on end. Calvin explained which of the cartridges was suited for what prey (the one used for elephants was the size of his forefinger), then excused himself briefly and returned with a battery-operated cassette player. La Coma is well known among Calvin’s friends for its quail and dove hunts. Following one of those weekend hunts, Calvin said, a famous guest had returned to his piano in Palm Springs and composed a personalized ditty about the outing for his Texas hosts. Calvin said the cassette had arrived in the mail not long before the entertainer died. He played it now as the last of the dinner guests gathered round to listen to the scratchy recording, to the tune of “Old Man River”:

But old Cal Bentsen showed him who was best,

’Cause he’s the fastest gun in the whole Southwest.

“That really is Bing Crosby,” said one of the guests.

“Of course, it is,” cried Jean. “Oh, it’s priceless.”

Rhino Sex

The morning after the party, I met Calvin at his ranch north of Edinburg to look at rhinos and to talk about breeding them. From the highway, La Coma differed from the neighboring brushy range only in its tall game fence and a sign warning trespassers of dangerous wildlife. The foreman, Andy McClellan, was a swarthy and wiry man who stuffed his jeans into the tops of his manure-splattered boots. Four years earlier Andy had been an ordinary working cowpoke. Now ostrich chicks about the size of geese ran around the yard of his mobile home. The fender of his pickup bore a jagged hole—the result of a kick by an impassioned male ostrich.

Andy labored on this particular morning in the loading pens under the supervision of a young man from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. They were spraying the cattle, as required by the quarantine, and it wasn’t pleasant work. The sun was hot, and the poison kept blowing back in the cowboys’ faces.

Andy took a break beside a large mesquite, not seeming to mind the smell of the severed African antelope heads that were rotting in the branches of the tree. Evidently the size of the trophies hadn’t merited taxidermy, so they would become sun-bleached keepsake skulls. Reflecting on the problems of breeding rhinos, he said that he was certain the cow at La Coma had been in heat at least once. Rhino cows ovulate in cycles of 20 to 35 days, and the estrus lasts only 24 to 48 hours. Pregnancy lasts about sixteen months, and the cows mother their calves for at least two years. As a practical matter, the breeders have to hope for one fertile night of passion every three or four years. When the female comes into heat, she signals her ardor with musky sprays of urine that carry six to eight feet.

Rhinos—when they finally mate—make up for their solitary ways, years of celibacy, and stormy courtships. Sometimes they swoon over on their sides, but usually they keep their feet. The cow squeaks and pants from time to time. The bull bites at the air; his fringed ears flap continuously. The breeders have been told to expect the act to last at least half an hour. Two Indian rhinos hold the unofficial record of 83 minutes. To Westerners, the great mystery of the rhinos’ plight has been how Asians could ever have come up with that absurd business of an aphrodisiac horn. Perhaps now we know.

Andy said that the cow at La Coma had commenced spraying and rubbing suggestively against the fence that separated her pen from the bull’s. The male lumbered right over.

For the life of him, Andy couldn’t make himself open the gate, though. “It’s an awful responsibility,” he told me. “All I’d been hearing was how they’d rage and fight. I was afraid they’d hurt themselves. Next time I reckon I’ll be ready.”

“Do you plan to watch?”

“Why, sure. I have to! If they start fighting and one gets the other down . . . uh, well, I don’t know what I’d do. Bounce BBs off their ass?”

The rhino pens were hidden in a stand of mesquites about a mile away. Each fence post consisted of three 200-pound lengths of oil field pipe that were welded together and rooted in a yard of concrete. The responsibility of housing black rhinos cannot be taken lightly. As Ed Wroe had said at the dinner party, “I think we need to get old Calvin about five million in liability coverage. Sure would be a shame if one of these things winds up in downtown Matamoros.”

Calvin shoved the sole of his boot against an unyielding rung. “A member of Game Coin donated the pipe,” he said, “and the fence still cost ninety-five thousand dollars. Zoologists think black rhinos really need more room than this to breed successfully—maybe a hundred acres to approximate their territories in the wild. You can calculate the cost of that. We’re hoping that as they become more adjusted, they won’t need quite so much fence. The next plan calls for larger pens with sectioned telephone poles and cross strands of elevator cable.”

A shirtless employee named Pancho Olegin was whacking at brush with a machete and dragging it up to the pens. In the African wild, black rhinos ate the leaves and branches of acacia trees. In South Texas, they selected huisache as the tastiest substitute. Huisache is a chaparral bramble with inch-long needle-sharp thorns. The rhinos munched it thoughtfully. Pancho knew the rhinos better than anybody at La Coma did. He slept at night on a cot in a nearby metal shed, and it was he who had run up to Andy’s trailer, tears streaming down his cheeks, when the old cow died. Calvin asked him in Spanish to rouse the male, who had arranged his lair in the thickest brush and did not venture out often in the heat of the day. With an offering of alfalfa, Pancho slipped between the pipe and walked bravely through the mesquites. “Hey, bull,” he called. “Come on. Bull.” He looked back at Calvin and shrugged. “No quiere.”

Pancho selected a fist-size rock and zinged it through the brush. There was an alarming meaty thunk. Taking no offense, the bull finally rolled over, snapping a few saplings, and followed Pancho’s trail of alfalfa. Almost twice the size of the cow, he weighed 3500 pounds. Pancho stood behind a safety barricade and fed him more hay on a pitchfork. The bull playfully hooked the lower rung of the concrete-rooted pipe, causing the ground to tremble.

Watching, I thought about how Tom Mantzel runs along an identical fence at the Glen Rose ranch, slapping his thighs and cavorting with his rhinos. Tom’s young male tosses his head and performs a silly tiptoe dance in response. The rhinos on both of the ranches are potentially dangerous but no longer quite so fierce. The translocation has changed them, as it has the men. Even crusty old hunters like Calvin and Harry have come to think of the rhinos more as pets than prey. Tom and Harry buried the hatchet not long ago at a Fort Worth dinner party of their own. Harry told Tom that he just didn’t have the heart to hunt in Africa anymore.

After Pancho finished feeding the rhinos, Calvin took me to the ranch house, which made the McAllen mansion seem a model of subtlety and restraint in the use of animal decor. The walls at the ranch were jam-packed with mounted antelope heads; the floor was covered with skins of lions and grizzly bears arranged so that gaping mouths with bared teeth greeted anybody who entered the front door.

Calvin talked about how he’d gotten his rhino, as he thoughtfully stroked the mane of a lion’s pelt. “We set out from Nairobi with three lorries, a professional hunter, and the usual assortment of trackers, gun bearers, skinners, cooks, and tire changers. It took us three days to find the rhino. At the end of the second day, we came in exhausted and slept hard. That night a male walked right through camp, fifty feet from the tents. In stalking rhino, you always want to be downwind. If they smell you, they’re either gone or charging. As we followed the tracks, we saw that this one had picked up a companion. We were in very thick brush. We walked or crawled a few feet at a time. We knew something was in there, because we saw a tickbird, which has a swooping flight like our woodpeckers. That meant we were on top of either the rhino or a Cape buffalo. I was about forty feet away when I saw the rhino bull. I shot him once through the neck with a Holland and Holland four-sixty double-barreled rifle. He went down, but the rhino he’d been traveling with didn’t like that one bit. We could hear it snorting and stomping around. The pro hunter fired in the air and finally scared the other rhino off.”

Calvin ran his fingers through the lion’s mane. “That was an ideal kill,” he said. “An old male, probably sterile, that was no longer of any use to the herd. But the great safaris are a thing of the past. Back then, the going price was a hundred fourteen dollars a day, so you might stay out for a month. Now it costs eight hundred to a thousand dollars a day. The people in charge of those African governments have tried to put the blame for their endangered wildlife on foreign hunters, but you don’t find us extinguishing a species for its horn. My hunting licenses helped finance their force of park rangers. Those are poor countries over there. Without that revenue, park rangers are a luxury item. Who stands to benefit? Why, the poachers!

“They won’t let us hunt at all in Kenya anymore,” he said ruefully. “And I sorely miss Kenya. I’d wake up over there and swear I was in South Texas. The vegetation and climate are similar; even the water tastes the same—which is how, as a conservationist, I came to want those black rhinos on my ranch. In their native land they don’t stand much chance.” He smiled and looked around at the antelope trophies. “I am aware, of course, that some people think horns ought to be growing on my head. Some might enjoy seeing my head mounted on that wall.”

He walked outside to his van. “You’re my friend,” he announced with solemn and atavistic formality, then he drove away. In my hand was a gift bottle of South African Zonnebloem wine. He left me feeling oddly sentimental. Calvin is a true rhinoceros. He’s the great white hunter, and like the strange creatures making hay of his huisache, that’s a vanishing breed.

- More About:

- Hunting & Fishing

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Hunting

- McAllen

- Fort Worth

- Edinburg