Featured in the Houston City Guide

Discover the best things to eat, drink, and do in Houston with our expertly curated city guides. Explore the Houston City Guide

In 1833, a rebellious German college professor boarded a ship to North America. Ferdinand Lindheimer, who would eventually become known as the father of Texas botany, fled to the United States when his reformist political beliefs put him at odds with his family and the German government. Ever the political agitator, he eventually made his way to the battlefield at San Jacinto, where he enlisted in the Texas Army. Though Lindheimer was a little late to the Texas Revolution—according to several accounts, he joined the day after Santa Anna’s surrender—his real contribution to the state’s history would come from his dedication to the native plants and animals he found here.

In the years following the war, Lindheimer began to make excursions out into the relative wilderness of nineteenth-century Texas, occasionally tagging along with groups from the southernmost band of Comanches, the Penatekas. European and American botanists hired Lindheimer to collect specimens, many of which taxonomists had never before seen, and to send them off to be catalogued. Described by contemporaries as a man with a rough exterior but a gentle voice, he’d wander out into the far reaches of the Texas countryside with a pull-cart full of pressing papers, coffee, salt, flour, and little else. At least 373 plant species were first identified based on Lindheimer’s collections, and dozens are named in his honor—including Lindheimer’s prickly pear, also known as Texas prickly pear, a variety of the official state plant. After helping Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels bring a group of German settlers to found the community that became New Braunfels, Lindheimer settled on two acres along the banks of the Comal River, where he planted a garden, edited a German-language newspaper, and continued to explore the flora and fauna of Texas.

Lindheimer’s gift was that he could walk out into a Hill Country field and see not just shades of green and brown, as most of us do, but endless variety. Anna Strong, a state botanist with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, says a big part of plant conservation is education: “If you don’t teach people about what is out there, then they won’t know to even care.” That’s where botanical gardens come in. In addition to beautiful displays, and behind-the-scenes research and archiving, botanical gardens educate visitors and build relationships between humans and plants.

Strong says that like a lot of her colleagues, she found her love of plants at an early age. When she would go on hikes as a child, her father, also a trained botanist, would point out different species. Strong recognizes the practical benefits, like food and medicine, that plants provide, but the kind of love she’s talking about is for the thing itself. “This is a fascinating thing that doesn’t have a brain, yet persists, and has the ability to keep us all alive without any awareness that it’s doing that,” she says. “I find that beautiful.”

So do the horticulturalists who tend to Texas’s many botanic gardens. From New Braunfels’s Lindheimer’s House Garden, where you can see at least five flower species named after the naturalist, to the cacti of the Chihuahuan Desert and the azaleas of East Texas, our state has a remarkably diverse and lush array of gardens. Below, we’ve rounded up sixteen of our favorites.

Amarillo

In the High Plains of the Panhandle, the Amarillo Botanical Gardens see a different kind of weather than most of the state. “We’re more like Denver than Austin,” says Greg Lusk, the garden’s executive director. With freezing winters and scorching summers, it’s not the easiest place to maintain a year-round garden, but Lusk and his team see it as an opportunity to cultivate plants that can’t handle the long-lasting heat in other parts of the state. The garden pays homage to its natural surroundings with a section of native plants set against a tile mural of Palo Duro Canyon, the natural wonder just thirty minutes south of Amarillo. But while many gardens want to draw visitors’ attention to the plants native to the region, Lusk also hopes visitors feel like they’ve been transported somewhere else. “That’s what we all look for, right?” Lusk asks. “Escape?”

To that end, you can wander a six-thousand-square-foot conservatory featuring tropical plants, a pond, and even a waterfall. “It’s set up kind of like walking through a jungle,” Lusk says. “It just gives that feeling that you’re somewhere else.” 1400 Streit Drive, 806-352-6513

Austin

There are roughly five thousand species of plants native to Texas, and the largest living collection of those—about nine hundred varieties—can be found at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in South Austin. Native plants have been the center’s focus since the former first lady founded it four decades ago, well before gardening with endemic species became fashionable. The spring and early summer bloom at the Wildflower Center is not to be missed. Bluebonnets, firewheels, and horsemint put on a dazzling show. But the center’s interim director, Lee Clippard, says late fall and winter may be his favorite time of year to wander through the 284 acres of garden paths and arboretum trails. Without the showy blossoms, one’s attention is drawn to the faded colors and infinite textures that have thrived in the state for eons. Clippard says it’s a place to “form bonds and memories, and kind of be a part of the landscape.” 4801 La Crosse Avenue, 512-232-0100

Another urban oasis in Austin, The Zilker Botanical Garden’s live oak–shaded trails wind through a variety of lush environments, including the serene tea house and koi pond of the Taniguchi Japanese Garden. It’s so peaceful here, with only the soothing sound of a small waterfall, that you’ll forget you’re in the middle of the city. 2220 Barton Springs Road, 512-477-8672

Corpus Christi

The South Texas Botanical Gardens and Nature Center occupies 182 creekside acres where the South Texas ranch lands meet the Corpus Christi Bay. Since the late eighties, this coastal garden has been introducing visitors to a growing array of native and exotic plant species. Its conservatories are home to thousands of orchids and hundreds of bromeliads. Two resident parrots, Fred and Ethel, welcome visitors to the formal garden, which also features a reptile house and butterfly garden. Guests can also explore local flora and fauna on the nature trails and boardwalks that stretch out into the surrounding wetlands. Michael Womack, the garden’s executive director, says one of the best things about the place, and about gardens generally, is that they’re always changing as new plants grow and bloom. “Every couple of months they’re going to look very different,” Womack says. “So, go visit gardens all across the state, and then start over and do it again.” 8545 S. Staples, 361-852-2100

Dallas–Fort Worth

When the Botanical Research Institute of Texas (BRIT) and the Fort Worth Botanic Garden officially joined forces last October, they created an organization that aims to be one of the preeminent research and display gardens in the country. Founded in 1934, the Fort Worth Botanic Garden is the oldest sizable botanic garden in the state. That history is perhaps best captured in the thirties-era tiered sandstone architecture of the campus’s rose garden, and the restored pools and walkways of nearby Rock Springs Woods. Patrick Newman, the organization’s new CEO, says the Japanese garden, with its bridges traversing the massive koi pond surrounded by cherry trees and Japanese maples, is among the most spectacular in the country.

BRIT, for its part, conducts extensive research, archiving, and seed-banking projects in Texas and throughout the world. “There are a lot of plants still in the world that have yet to be discovered,” says Newman. That’s why BRIT teams can be found on plant expeditions across the globe, looking for new species. Newman says it’s important work because “the better we understand the plant world, the more we understand ourselves.” 3220 Botanic Garden Boulevard, Fort Worth, 817-463-4160

With 43,000 members and over a million visitors every year, the Dallas Arboretum and Botanical Garden is a much-beloved urban escape. Stretching out over 66 acres on the shore of White Rock Lake, the arboretum features a series of interconnected garden beds teeming with flowers. “We probably have more flowering plants planted in our garden than any other botanic garden in the country,” says the vice president of gardens, Dave Forehand. In anticipation of spring, gardeners plant more than 500,000 blooming bulbs, then change out the beds several times more throughout the year. “When people think of Dallas, they’re not thinking so much about beautiful flora and fauna,” Forehand says. “But we actually are changing that perspective.” 8525 Garland Road, Dallas, 214-515-6615

El Paso

In addition to some 3,500 plant species, 1,000 of which grow nowhere else in the world, the Chihuahuan Desert is also home to a dramatic array of wild animals that rely on those plants for sustenance, or for the sustenance of their prey. The El Paso Zoo and Botanical Gardens is the best place to see those creatures on display among their native flora. The zoo’s Chihuahuan Desert exhibit showcases jaguars, wolves, and cougars prowling among ocotillo and prickly pear. The zoo and botanical garden is also partnering with Bat Conservation International to help protect Texas’s only endangered bat species, the Mexican long-nosed bat. These tiny flying mammals feed on the nectar of the agave flower, the supply of which is diminishing as development and agave harvesting encroach on their habitat. With its joint focus on plant and animal life, the El Paso Zoo and Botanical Gardens was a perfect institution to partner with BCI to help restore agave habitats throughout the Trans-Pecos region, and it has added a new agave-centered pollinator garden onsite. 4001 E. Paisano Drive, 915-212-0966

El Paso has several other great places where you can wander among the native desert flora, including the University of Texas El Paso’s Chihuahuan Desert Gardens and Keystone Heritage Park’s Desert Botanical Garden. Both display a seasonal variety of endemic plants. 500 W. University Avenue, 915-747-5565, and 4220 Doniphan Drive, 915-584-0563

Fort Davis

Set among five hundred acres of igneous rock outcroppings in the Davis Mountains, the Chihuahuan Desert Nature Center and Botanical Gardens has five miles of trails twisting through the yucca, agave, and native grasses. “We’ve got some unusual plants here,” says director Lisa Gordon. “There’s plants that are relics of the ice age that are still here.” A highlight is the Cactus Museum Collection, a 1,400-square-foot greenhouse featuring hundreds of species of cacti from across the Chihuahuan Desert, which is North America’s largest. The path leading to the greenhouse winds through native oaks, pines, big tooth maple, and Arizona cypress before reaching the pollinator garden. “It’s just quite an interesting region, it’s quite diverse, and we want people to be aware of what’s out here,” Gordon says. 43869 Texas Highway 118, 432-364-2499

Houston

The diversity of the Bayou City has long been one of its defining characteristics, so it’s fitting that the Houston Botanic Garden chose diversity as a design emphasis. This theme is especially prominent in the global collections gardens, a centerpiece of the 132-acre grounds featuring flora from all over the world. The garden, designed by Dutch architecture firm West 8, opened to the public in September 2020. It wasn’t easy to open a venue during a pandemic, but the garden’s team saw it as an opportunity to provide a safe place for visitors to discover something new. “People were clearly hungry to get outdoors,” says Justin Lacey, director of communications and community engagement. Perusing the global collection, and its elaborately designed covered walkway, Lacey jokes, “you can go around the world in three acres.” 1 Botanic Lane, 713-715-9675

Just outside the Houston city limits, the trails and boardwalks of Mercer Botanic Gardens sprawl over four hundred lush acres, which are managed by Harris County, and where admission is free. Over the years, the garden’s staff have been frequent collaborators with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department on plant conservation and research projects, and Mercer is host to a native and endangered species garden. Eclectic touches are scattered throughout the grounds, including a small plot near the entrance that is filled only with species named in the plays and sonnets of William Shakespeare. 22306 Aldine Westfield, Humble, 713-274-4160

Mission

The National Butterfly Center in Mission is perhaps the best example in the state of a botanical garden whose principles embrace the messiness of nature. “We can try to impose order,” says executive director Marianna Trevino-Wright, “but the pollinators don’t really stand for that.” Established two decades ago as a sanctuary for the huge variety of butterflies that reside or migrate through the Lower Rio Grande Valley, this one-hundred-acre nature preserve and botanical garden is home to more than three hundred species of plants native to the region, including Turk’s cap, milkweed, and Texas lantana.

The center’s grounds back up to the Rio Grande, and starting in 2017 Wright and her team became activists fighting border wall construction plans in the area, filing lawsuits against the government and private contractors, and calling attention to how the wall would adversely affect the sensitive borderland ecosystem. Thanks to Wright’s efforts, the river remains accessible at the butterfly center. The floating dock and riverside bench are popular with the bird watchers, schoolchildren, and families who frequent the garden. Visitors can also wander through wooded trails and escape the South Texas winds at the sunken gardens. And, of course, “everywhere you go, you’re going to encounter the butterflies,” Wright says. “They’re just flying around.” 3333 Butterfly Park Drive, 956-583-5400

New Braunfels

Historical conservationists don’t know exactly what Ferdinand Lindheimer planted in his home garden, but today the Comal Master Gardeners maintain the vibrant plot next to his gray stuccoed house with blue painted windows. You can schedule a tour of the home, which still has some of his original plant pressings on display, through the New Braunfels Conservation Society, but there’s no appointment necessary if you just want to peruse the riverside garden. You’re likely to find a number of species named after or collected by Lindheimer himself, including Lindheimer’s daisy, silk tassel, morning glory, guara, and beebalm. Crushed stone paths dissect the garden’s various beds, and lead to the oak-shaded backyard, which drops down to the river. 491 Comal Avenue, 830-629-2943

Orange

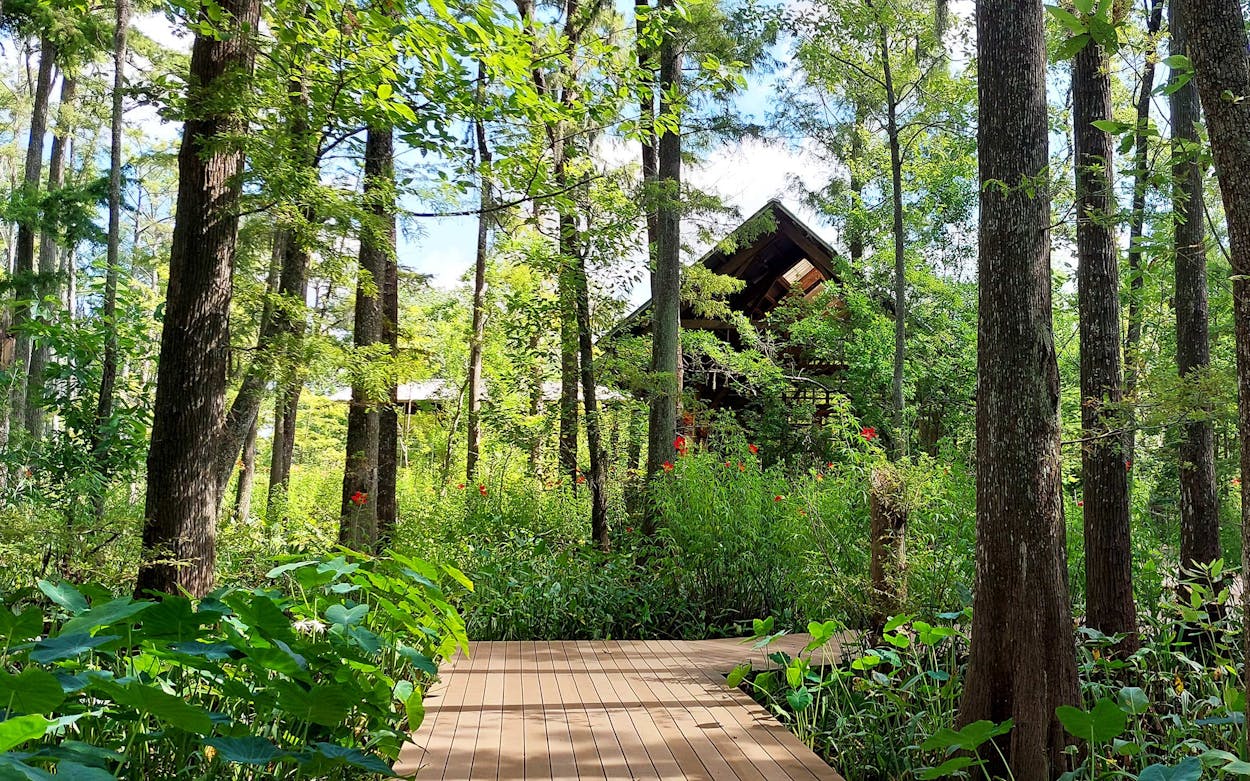

Shangri-La, the mystical mountainous utopia described in James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon, made such an impression on Orange businessman and philanthropist W.H. Stark that he named his capacious personal garden after it. In the 1940s and 1950s he opened his Shangri La to the public, allowing Orange residents to saunter among the blooming azaleas. After a devastating winter storm left Shangri La shuttered for decades, the Nelda C. and H.J. Lutcher Stark Foundation hired San Antonio–based architecture firm Lake Flato to design structures that would reinvigorate the 252 acres in Southeast Texas. In 2008, Shangri La Botanical Gardens and Nature Center began once again to welcome guests to this ecological oasis.

The grounds exhibit some of the otherworldly opulence of the fictional Shangri-La. Monstrous blooms spill out of elephant yams and corpse flowers. Visitors can spy alligators and shorebirds from the Heronry Blind, tucked beneath towering cypress and tupelo trees on the edge of Ruby Lake. And tropical and subtropical plants overflow stone terraces at the hanging garden. When ginger flowers are blooming, Shangri La’s interim executive director, Jennifer Buckner, likes to take in the intoxicating aromas while sitting on a bench tucked on the edge of the lake’s cove. “It’s just a nice little nook,” she says, “But, man, when those gingers are blooming, the smell is wonderful.” 2111 West Park Avenue, 409-670-9113

San Antonio

Marigolds, agave, and bougainvillea adorn stuccoed structures at “Frida Kahlo Oasis,” the San Antonio Botanical Garden’s current exhibition (on display through November 2). The project explores how the vegetation at Casa Azul, Kahlo’s legendary Mexico City home, influenced the iconic artist’s work. The exhibition is just one aspect of a garden that offers a little bit of everything. On these 38 acres at the center of San Antonio, garden trails unwind in every direction. Near the entrance, the culinary garden and teaching kitchen hosts local chefs who guide cooking classes using ingredients grown just a few steps away. Children play among the plant life in the Family Adventure Garden. The Texas Native trail curves through a Hill Country habitat and South Texas brushlands, but also loops around a lake situated in the East Texas Pineywoods section. Meanwhile, the towering glass structures of the garden’s conservatory house orchids, palms, cacti, and ferns from all over the world. 555 Funston Place, 210-536-1400