When Danielle Prewett and I talked, Instagram was down. There had been some sort of internal meltdown at Meta, and Instagram and Facebook were suddenly inaccessible. The outage was a minor inconvenience for most casual Instagram users, who use the app primarily as a way to distract themselves between meetings, to online shop, or to see what their ex has been up to. But what was it like for Prewett, a cook, blogger, hunter, and influencer (she doesn’t love that word, but we’ll get to that later) who has amassed a significant following on the platform and owes much of her success to it?

“What a relief, really,” she laughed, at her home outside of Houston. “The world needs a day off.”

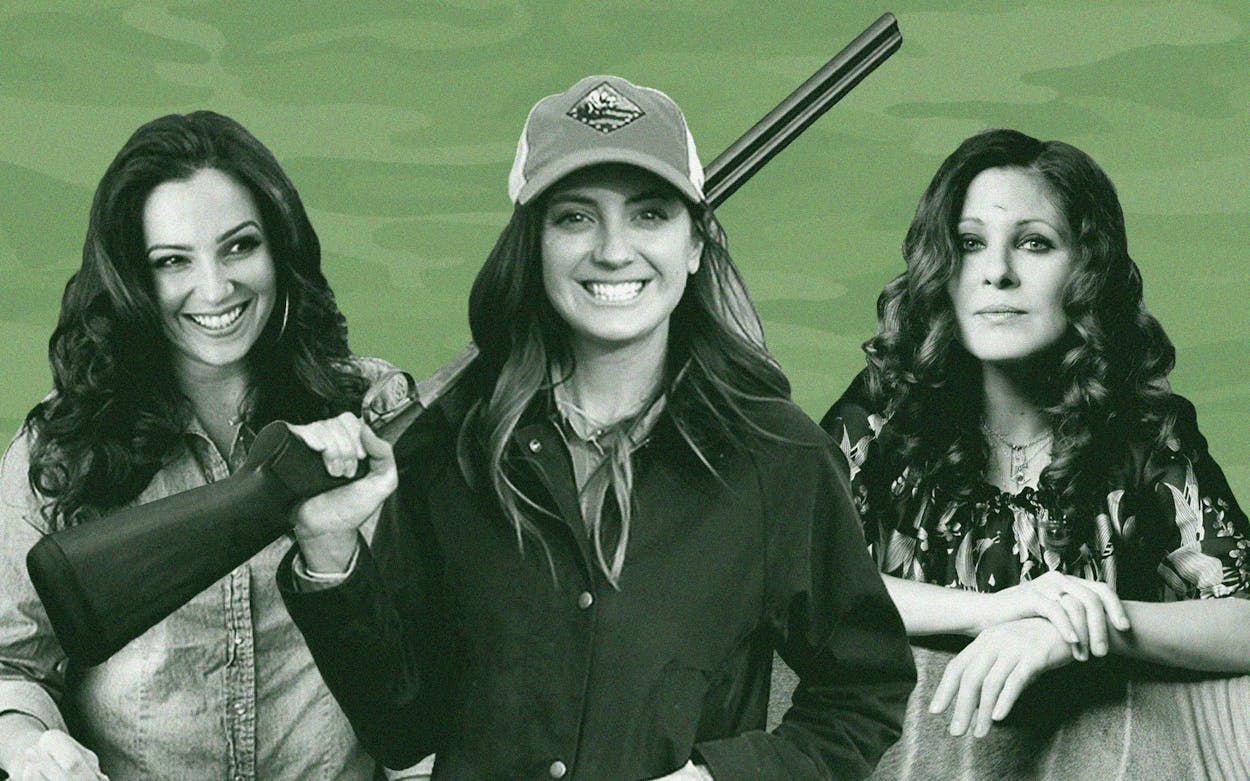

Prewett, who is the wild foods contributing editor at the website MeatEater and founder of the food blog Wild + Whole, is at the forefront of a growing number of women touting the wonders of wild game on social media. Her Instagram—when it’s up and running—has over 118,000 followers, and is a mix of hunting photos and close-up shots of exquisitely prepared game. In one, she shows off an enormous slab of elk meat the size of a parking meter; in another, she shares videos of how she prepared some delicate squash blossoms.

While it’s by no means unusual to see women in the hunting and game space, the field remains largely male-dominated, both in terms of the audience and in the type of content that gets put out. “Most of the time you think of hunting as a very masculine thing,” Prewett says. “Their recipes tend to be burgers, poppers, or something fried. And so I wanted to make something practical that would be more universal, that’s not just geared to a man’s palate. I wanted to make this more approachable for a wider audience.”

But Prewett and her peers with whom I spoke were loath to emphasize the role their gender plays in their work. “I wanted to be in this space because people respected what I was capable of doing, and not just because I was a woman,” Prewett says.

Instead, Prewett says she aims to make wild game and foraged vegetables more accessible and delicious to hunters and non-hunters who might be intimidated by the less-familiar foods and unsure how to prepare them.

The appetite for this type of content has never been greater. During the pandemic, restless Americans tired of being cooped up at home rushed to acquire hunting and fishing licenses. One report found that nationally, hunting-license sales rose 5 percent from 2019 to 2020, and according to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, sales of “super combo” license packages—which bundle together, among other things, resident hunting and fishing licenses—rose from 437,896 in the 2018–19 season to 473,180 in the 2020–21 season.

The growing interest in hunting doesn’t surprise Prewett, who sees it in part as a survival response to all of the chaos and uncertainty of the past two years.

“People are wanting to get outside and be more self-sufficient,” she says. “We saw what happens when the supply chain goes crazy. How do you get your food? Hunters know how to get their food.”

Prewett herself first started hunting when she moved to North Dakota from Houston with her husband nine years ago. There, she says, the pace of life was slower, and there was more public land to access. The couple got a bird dog, and Prewett started accompanying her husband on “upland hunts”—hunts for birds like quail, pheasant, grouse, and chukar. She still remembers fondly one of her first hunts, when her dog flushed a pheasant out of the cattails and she shot it. That night, she used the bird to make coq au vin. The meal was transformative. “I remember the first time eating this bird, it was the first time I was eating my bird, and I just can’t describe the overwhelming feeling of gratitude and appreciation for that meal,” she says. “It was just an aha moment of realizing that food can carry a lot of meaning. And I wanted to eat this way forever.”

From that point on, Prewett started hunting more and more, and she eventually told her husband she wanted to start living off the land, hunting and fishing all of their own protein themselves. It’s a decision that stuck. Since then, they’ve hardly purchased any meat from grocery stores, apart from the annual Thanksgiving turkey.

At first, her friends and family didn’t fully understand Prewett’s new approach to food. “They all thought I was crazy,” she says.

As time went on, out of both necessity and passion, Prewett started learning more and more about the nuances of cooking nose to tail, like how to deal with tougher cuts of meat and the wonders of pan roasting. She started sharing some of her tricks and recipes with friends whose husbands and family members hunted, and who didn’t know how to prepare the venison and fowl they brought home. Eventually, within a week of each other, both her brother and best friend told her that she should start a blog to share what she had learned.

“At first I really didn’t want to do it,” she says. She’s a private person, and the idea of putting her thoughts out there was intimidating. But she saw a gap in the market, one she believed she could fill with her refined recipes geared to hunters who wanted more than just a burger.

The desire to make wild game and meat cookery more approachable to a wider audience was also one of Jess Pryles’s main motivations when she started sharing her hunting and cooking stories on Instagram. Her grid is a mixture of sumptuous close-up photos of steaks, ribs, and burgers; shots of her hunting; and videos of her speaking into the camera, sharing cooking tips, and debunking popular meat myths. (In one, she replies to a TikTok in which a woman asks what is actually in a McRib: “It’s pork,” she says. “I don’t understand why people try and make out like it’s mystery meat.”)

When we met for coffee in early October, Pryles, who is from Australia, said she always loved cooking, but she grew up feeling confused and intimidated by the meat she saw in the grocery store. She didn’t know how to prepare steak, how long to cook it, or what the difference was between a New York strip and a ribeye. Then she traveled to Texas, had real Texas barbecue, and her whole life changed for the meatier.

The more she learned about barbecue, the more fascinated she became with the complexities of meat—how best to raise the animals, kill them, and prepare them. She visited a slaughterhouse to see how cattle were processed, and she practiced different meat recipes and preparations. As she learned, she documented her carnivorous journey on every social media platform there was, and eventually developed a large and loyal following of fans eager to learn along with her. Now, Pryles’s life revolves around meat: she has over 146,000 followers on her food-centric Instagram, she’s getting her graduate degree in meat science from Iowa State University, and she’s running Hardcore Carnivore, a line of meat seasonings she developed herself.

Even as she started proselytizing for the miracles of meat, she knew her education wouldn’t be complete until she hunted. She was driving through North Austin with a friend one day, marveling at all the deer around her, when she decided it was time to go on a hunt. “I’d like to prove it to myself,” she remembers thinking. “And if I’m going to continue to preach meat eating, I would like to be able to go through the entire process.” Her first time out, she managed to down a doe. She’s been a hunter ever since.

While Pryles and Prewett mostly shy away from political content on their platforms—a safe bet when courting followers and advertisers from across the political spectrum—other accounts take a more outspoken approach. Ashley Chiles, founder of the Texas Huntress, the brand under which she writes, designs, and produces short films, has over 36,000 followers on Instagram, and says her outspokenly liberal content has been central to her brand ever since she started posting about her hunting journey on Facebook in 2010. (Her Etsy shop once sold a “F— Trump” trucker hat.) “People respond to my authenticity and my lack of bullshit,” she said over the phone.

Chiles grew up in Houston, and while she came from a family of hunters, she didn’t start hunting until she was an adult, after she started learning more about sustainable farming and ethical consumption. Put off by factory farming, she concluded: “I have to hunt, or I have to stop eating meat.”

While hunting was always central to her brand, she says hunters alone were never her target audience. “It was never hunting people who followed me, it was just people,” she says. “It’s important for people who are consuming meat to think about these issues.”

Prewett says she understands the pressure some influencers feel to perform, a pressure that she argues then trickles down to followers, who expect themselves to be able to re-create similar experiences. “With hunting, you’ll see a picture of someone with a giant buck, and you’re like, ‘Wow, that’s amazing.’ But what you don’t see is: Where did they hunt that? Did they have a guide? Did they hunt behind a feeder? People don’t always share those details, and to expect other people to go out on a public-land hunt and be able to replicate that same thing is slightly unrealistic.”

She felt that pressure herself when she went on a chukar hunt in Idaho once. It was a tough hunt, with ten-to-twelve-mile hikes each day, and after several days without shooting anything, she had to go home empty-handed. “I’m supposed to be, like, Ms. Annie Oakley over here, and I’m not,” she says. “It was just extremely painful to think about how hard I worked over the course of a few days, to miss a bird on camera, and it sucks. You want to cry a little bit. But I think what people appreciate is the authenticity, because everyone’s been there.”

As a woman, she says, she also had to figure out early how to present herself. Because the audience for hunting and game content is primarily men, there can be pressure on women representing brands to look or act a certain way. As Prewett puts it: “It’s really easy to sex up the female.”

Prewett acknowledges she felt some of that pressure early on. She wondered whether she would have to wear makeup and more-revealing clothes on hunts if she wanted sponsors. She quickly decided, though, that that wasn’t for her. “I don’t think there’s anything wrong with wearing makeup while you hunt,” she clarifies. “It’s just that I don’t do it, so I don’t think it’s right for me to put on makeup and parade around the internet like that.”

That kind of pressure is part of what made Pryles reluctant to post pictures of herself on Instagram at first. She wanted to be followed and respected for what she knew and what she did; she didn’t want what she looked like to be part of the equation at all. She’s mellowed a little over time—she regularly posts pictures and videos of herself now—and says that as far as the gender dynamics go, “things even out in the wash.”

“There are opportunities that have probably been given to me because I’m a woman. If a brand is worried they have too many male ambassadors, they can throw me in there. But for every one of those, I’ve lost an opportunity because I couldn’t be in the boys’ club and schmooze my way to new opportunities.”

Prewett hopes that sharing her own failings and misfires will help inspire other people—other women, specifically—to get out and enjoy hunting, and to feel confident in preparing the meat they bring back. Still, as passionate as she feels about her work, she concedes that the Instagram blackout was a bit of a relief.

“The lines between my personal and my professional life on social media are a little blurred,” Prewett admits. “It’s refreshing just to put it away for a while.”

- More About:

- Hunting & Fishing

- Hunting