“Terry Malick and James Turrell have been talking about doing a movie,” said Hiram Butler of the Hiram Butler Gallery in Houston, referring casually to the Austin director Terrence Malick. Butler, wearing a bowtie, has represented Turrell for 28 years and has been instrumental in establishing Turrell’s reputation, having sold more of Turrell’s art than anyone else—mostly to Texans.

Turrell tried to come up with a name. “Who was in Tree of Life? Who’s the actor?” he asked those eating breakfast at the Driskill Hotel the day before the October 19 opening of “The Color Inside,” his 84th “skyspace” work at the University of Texas at Austin.

“Brad Pitt,” Butler answered.

“I need my glasses,” Turrell said, swiping a finger across his iPhone screen. As usual, the white-bearded artist was dressed in all black. Or maybe his blazer was navy. As with his works, which orchestrate light, sometimes in colored sequences that play with a viewer’s perception, the juxtaposition of his shirt, pants and blazer—all various shades of night—makes it hard to tell.

What kind of film, we don’t know, Turrell said. “Tree of Life was his utopian movie and artists are always thinking of these utopian projects.”

He handed me his phone: “Oh my God,” I said.

“It’s not your God,” Turrell, a Quaker, laughed. “But it is Brad Pitt.” Brad Pitt holding a magazine with Turrell’s face on the cover. One of Malick’s assistants had sent it.

Turrell, 70, has been acclaimed almost since the moment he began practicing 48 years ago (in 1984 he and Robert Irwin were the first visual artists to win a MacArthur Genius Grant). But this year he has become a mini-celebrity with an unprecedented three concurrent shows at major U.S. museums—the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Guggenheim. The museums in Los Angeles and New York give him updates. His New York show drew the most visitors in the Guggenheim’s history—700,000. “But LA gives me the celebrity watch,” Turrell said. Not that he can remember their names.

Texans, though, have long appreciated the artist. (Malick is far from the first.) The Dia Foundation, which has deep roots in Texas, bought the Arizona land in 1977 for his lifetime undertaking, the Roden Crater, an experiential piece in an inactive volcano. (When the foundation, backed by Schlumberger Oil, fell into economic trouble during the gas crisis of the eighties, Turrell became a cattle rancher in order to qualify for a low-interest loan to take over the lease.) His biggest collector was the late Isabel Brown Wilson of Houston, who donated fifteen works to the M.F.A.H., making it the museum with the most Turrell holdings. Now, Turrell’s biggest living collectors are Austin’s David Booth and Suzanne Deal Booth. (The latter donated “Twilight Epiphany,” the 125-person skyspace at Rice, what Turrell calls “my first really successful public outdoor work.”)

For his part, Turrell believes Texas “is very important. Art does, to some extent, follow economics,” he said. It’s “the most postponable purchase.” Though most artists “may have strong social leanings,” Turrell said, artists “can’t function in an environment that is difficult on business.” Booth, for instance, moved his company, Dimensional Fund Advisors, from California to Texas, presumably for the business climate. “You’re going to have to put up with your Rick Perrys and we’re going to have to”—Turrell paused and smiled—“Cruz on through.”

Artists, art gallery dealers and collectors must be entrepreneurs, Turrell added, and nowhere more so than in Texas, which does not have the same institutional legacy as a city like New York. But “Texas is known to throw money,” at both artists and professors, Turrell said. “This is why Texas is most respected and feared”—even disdained, as was the case, he said, with the MFAH. “That happens with success.”

“The Color Inside” was commissioned in September of 2008, by Landmarks, an initiative to install contemporary art on UT’s campus. Director Andrée Bober started the program with a long-term loan of 28 modern and contemporary sculptures from New York’s Metropolitan Museum. Since 2005, the university has set aside one to two percent of their building funds for the acquisition of public art.

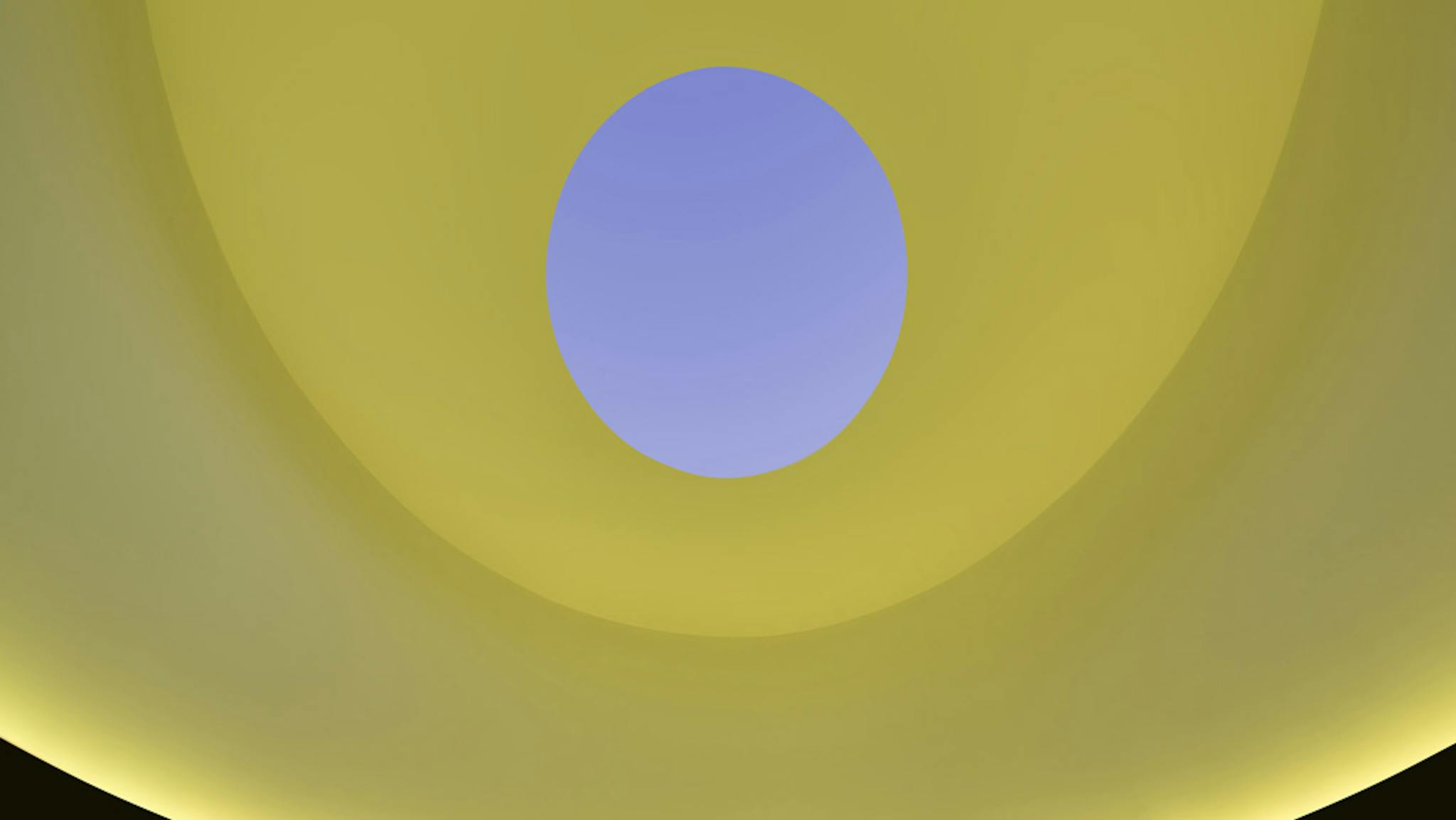

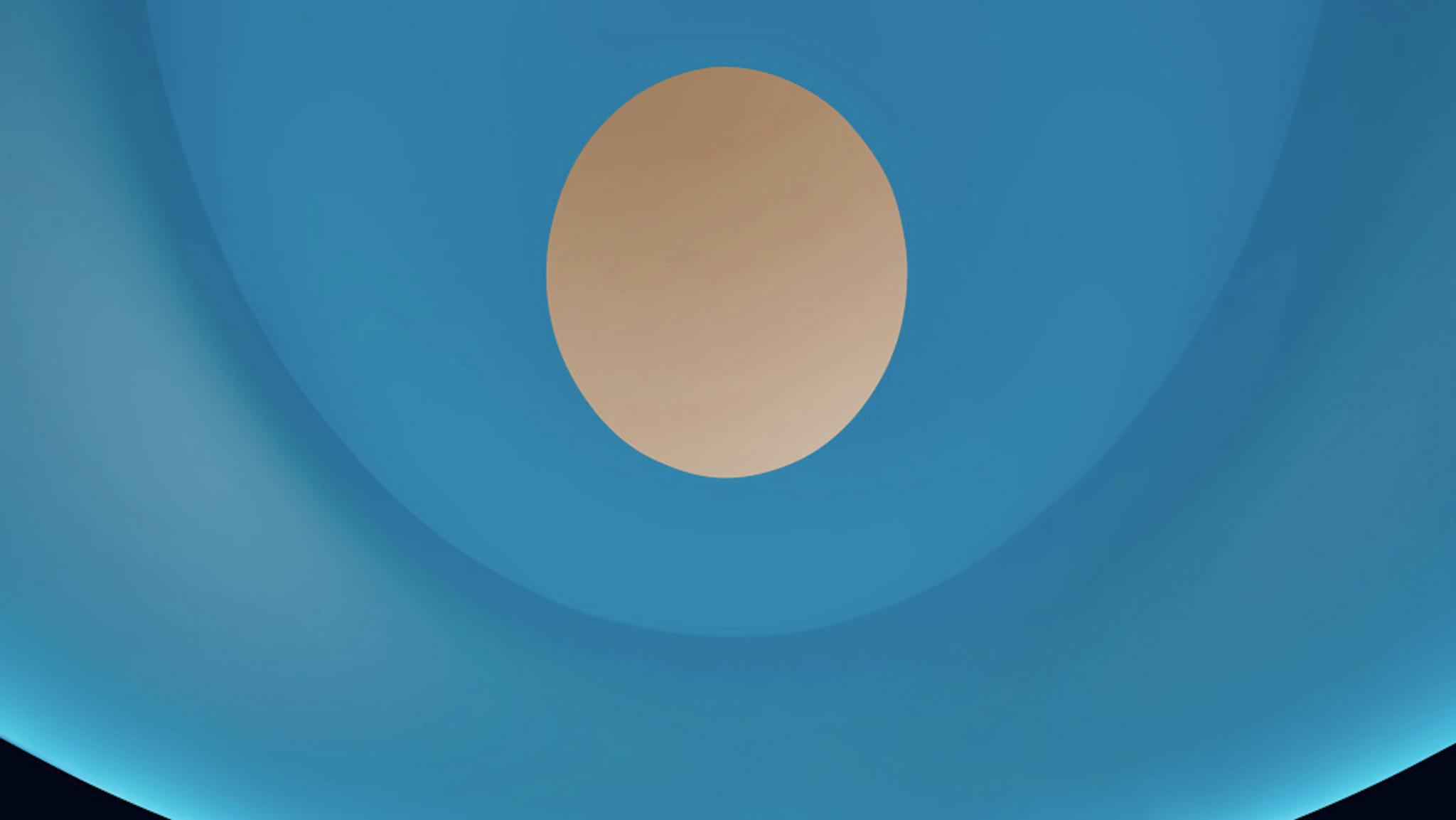

James Turrell, Interior of “The Color Inside,” 2013; Photo by Florian Holzherr

The skyspace was Bober’s answer to students’ request for a prayer and meditation room in the new Student Activity Center. Students journey through the building to find Turrell’s white cocoon on the roof. “The Color Inside” fits 25 and is open during building hours, though it is only art during sunrise and sunset—the transition from “God’s light, or the light of the sun” to our more “insignificant” light.

Turrell programmed its approximately hour-long computer-controlled LED light sequence while observing the Austin skyspace over seven mornings and seven nights in August. The work, Turrell said, is “formed by the viewer. You put the camera up there and that color is not there. It’s only in our mind.”

Turrell is most interested—as evident in his forty years of work on the Crater—in creating the sort of place, like Machu Picchu or Angkor Wat, that connects a viewer to something bigger. “Artists have always been involved in these higher purposes, and if you address the higher part of someone’s thinking, it often answers you.”

For that reason, in 2002, Bober chose to get married in one of his pieces: the Live Oak Quaker Meeting House in Houston, as did Butler five years later. In fact, there have been eight marriages at New York’s PS 1, the first U.S. skyspace, six at the Crater, and the MFAH retrospective closed for fifteen minutes this summer so a man could propose while Turrell’s “Ganzfeld” room was pink. “I have been asked twice to be the godparent of a child that was conceived in the PS1 piece,” Turrell added, laughing. “So the uses of these works is myriad.”

After announcing “The Color Inside,” “One of the first emails we received,” Bober said, “was from a young man who said that he and his partner had been together for fourteen years, and that he was ready to propose.” He asked if he could reserve the skyspace.

Turrell, who has oft been likened to Santa Claus, turned to Bober and said, “Sure.”

- More About:

- Art