Some visitors to the Kimbell Art Museum, in Fort Worth, are often left wondering what made a bigger impression: the word-class art collection—antiquities and works from Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Pre-Columbian period—or the building itself, designed by the master architect Louis Kahn. A new exhibition opening this weekend at the museum, “Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture,” makes a compelling case for the latter.

“If one thinks about architecture and the possibility of achieving great art in architecture, one would say that the Kimbell Art Museum is one of the greatest buildings in the United States and certainly, I would argue, probably the greatest building in Texas,” says William Whitaker, the curator and collections manager of the architectural archives of the University of Pennsylvania School of Design, which includes the Louis Kahn archive. “It’s got this incredible fusion, or integration, of landscape and building.”

The way to the main entrance of the museum is like a walk in the park: Pass through a grove of trees, continue on beside pools of cascading water, hear the sound of gravel crunching underfoot through the courtyard. Kahn’s goal with this progression is that by now the museumgoer has reached a state of serenity. The mind is clear and prepared to take in art. It’s time to enter.

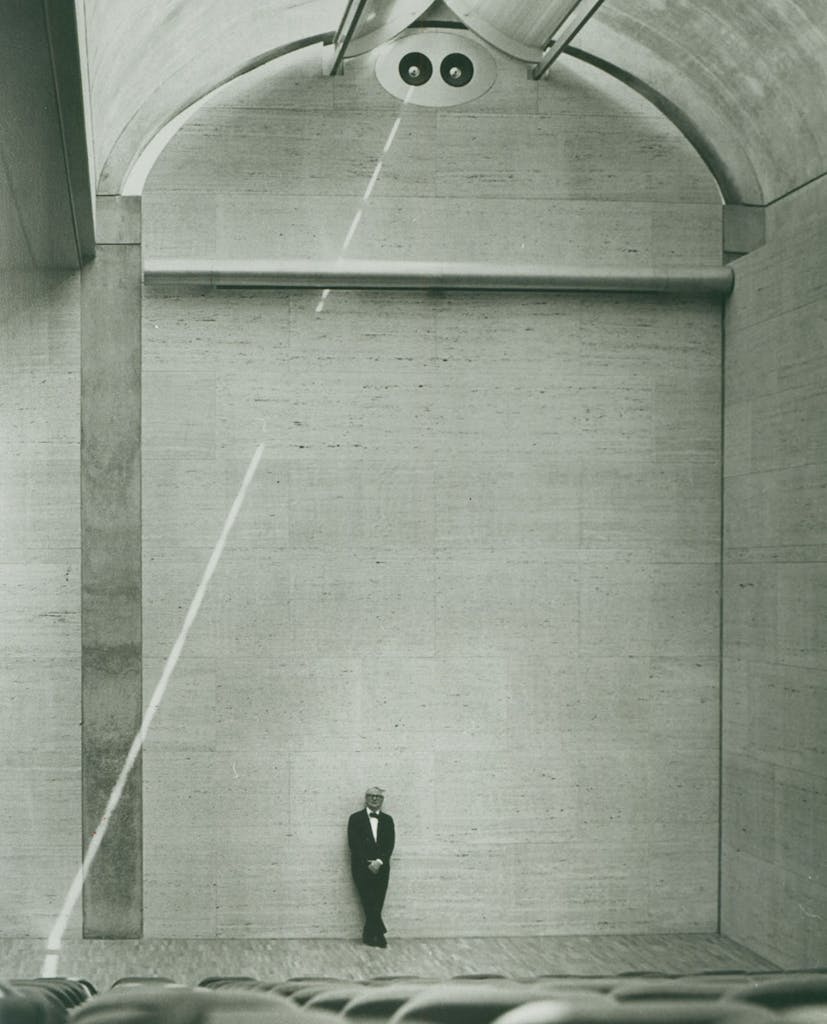

The museum can be seen as a case study in symmetry. The galleries are each exactly one hundred feet long and about twenty feet wide. They all have semicircular ceilings, or “vaults,” composed of concrete that’s been manipulated into an improbable form and scale. A strong sense of order is established with a spare materials palette: travertine, concrete, stainless steel, and white oak. Light passes through openings in the ceilings and long, narrow windows running along the walls. Three courtyards within the building aid in bringing the outside inside.

Museum, in 1972.Photograph by Bob Wharton/Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth

“There is probably no building that captures natural light so beautifully as this building,” Whitaker says. “It’s so responsive to natural light that just the subtle changes of a cloud passing over and covering the sun, you can feel that in the building. That change of light quality animates the space in a very beautiful way.”

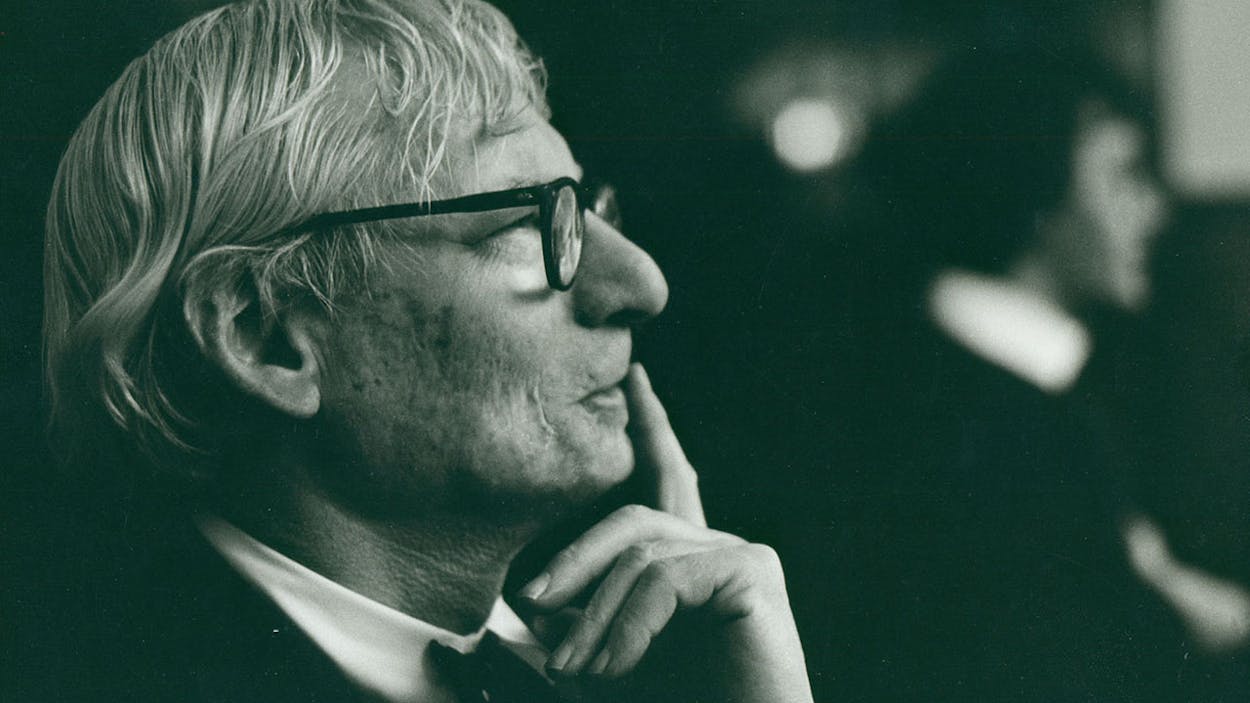

Kahn is an ideal example of the way immigrants have helped to shape the United States over the years. He was born in Estonia, in 1901, but in 1906 his family moved to Philadelphia. His drawing skills were nurtured in the public school system, and a class on architectural history during his senior year hooked him for good. He went on to the University of Pennsylvania, where Paul Cret, the architect who designed the University of Texas at Austin, became his mentor.

Upon graduating from Penn, in 1924, he worked apprenticeships, and in 1930, at the height of the Great Depression, he went off on his own. He completed very little the first fifteen years of his career, but by the late fifties (more than two-thirds of the way through his life—he died in 1974) he hit his stride. When he received the commission for the Kimbell, in 1966, he was at the height of profession, with two other monumental works already underway: the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, in La Jolla, and the National Assembly building, in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

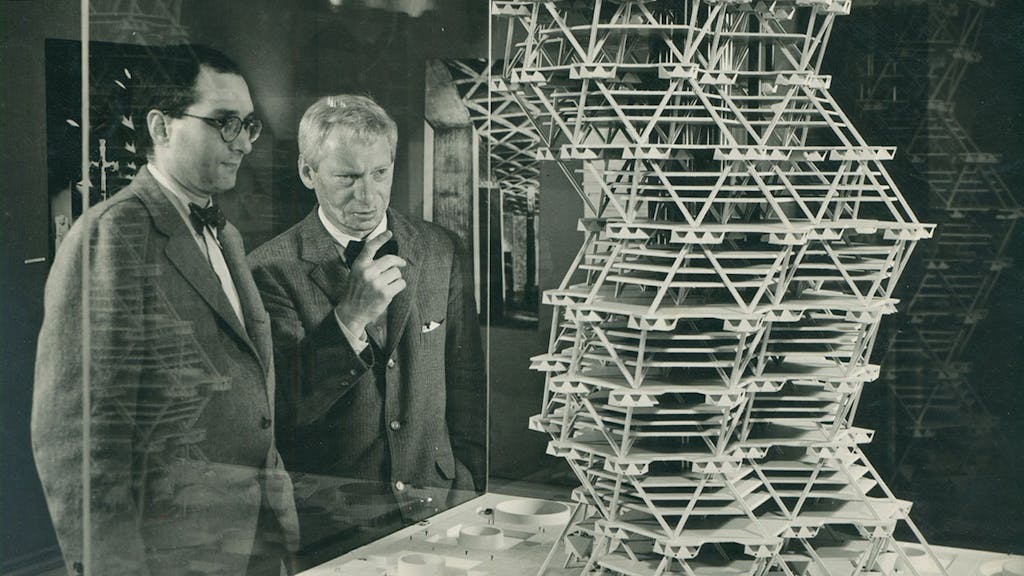

The Kimbell exhibit, organized by the Vitra Design Museum, in Germany, in cooperation with the University of Pennsylvania and the Netherlands Architecture Institute, examines Kahn’s work from an intellectual standpoint and explores how it is relevant today. There are original drawings and models, including the twelve-foot-high City Tower, a never-realized futuristic work that he collaborated on with his lover, the architectural theorist Anne Tyng. In addition, there will be watercolors and pastels Kahn completed during his travels.

This Saturday the Kimbell will host a symposium to open the exhibit. Whitaker will be there, along with Wendy Lesser, author of You Say to Brick: The Life of Louis Kahn, and Jules Prown, an art history professor at Yale University, home to Kahn’s final building, the Yale Center for British Art. There will also be a discussion with Kahn’s three children, including the filmmaker Nathaniel Kahn, whose Oscar-nominated documentary, My Architect, delves into the life of his father. A screening of the movie will take place on Sunday.

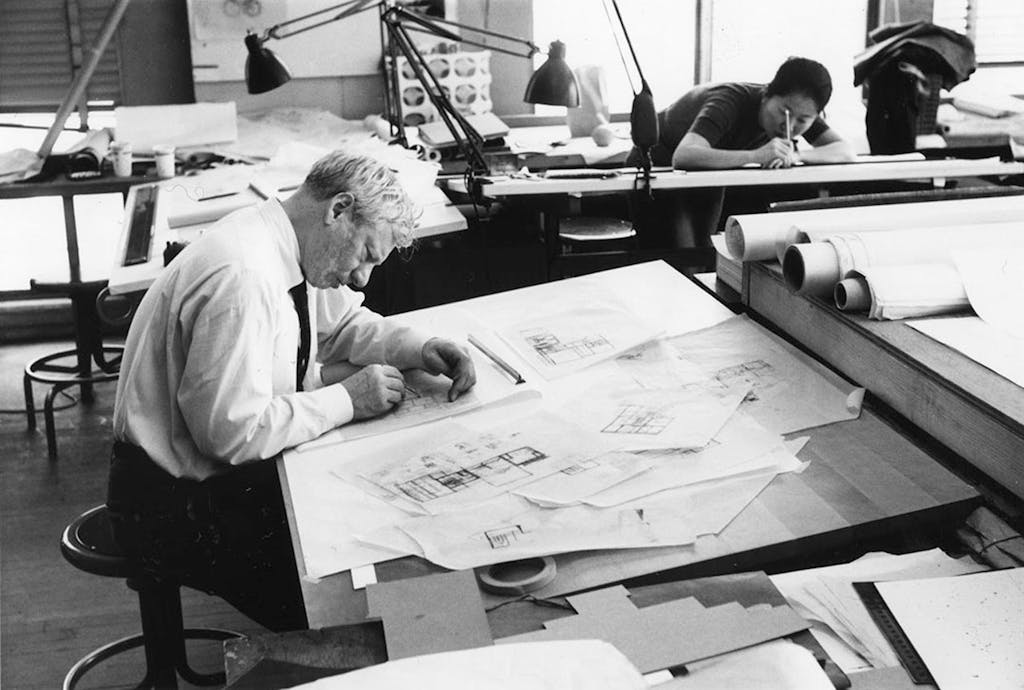

“Kahn’s famous for taking a long time to design his buildings because he’s really thinking about every last detail,” Whitaker says, “There’s a wonderful scene in the film with three guys who were very much involved with the construction of the Kimbell and they’re almost making fun of Kahn and his way of laboring over the decision about which screw head to use, whether it should be a hex head or a Phillips head.”

The exhibition includes new footage culled from the making of the documentary. Visitors to the museum will see three mini-movies focusing on the Kimbell, the National Assembly building, and the Fisher House, a private residence in Pennsylvania that took four years to design and three years to build. Each film shows the living, breathing buildings, filled with their inhabitants, with their surroundings taken into consideration.

The Kimbell Art Museum came to be only a decade after the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, also in Fort Worth, designed by Kahn contemporary Philip Johnson. They share the same block with the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, by the Japanese architect Tadao Ando, which opened in 2002 and created a triumvirate of buildings whose architectural excellence rivals their artistic contents. To see Kahn’s life and work in the confines of his greatest work inspires revelations.

“There are many buildings nowadays that are designed just to be spectacles, just to be a thing that looks extraordinary from a distance, but as you enter, that sense of spectacle doesn’t create that sense of transformative experience in the way that Kahn’s buildings can,” Whitaker says. “Kahn is an architect that a lot of architects look to, because he’s doing it in a way that every architect wishes they could do it.”

Kimbell Art Museum, March 26 to June 25, kimbellart.org

OTHER EVENTS ACROSS TEXAS

AUSTIN

Fore the Sake of the Game

By many people’s standards, golf is a rich man’s game, in part because affordable public courses are a dying breed. Ensure the next round of Jordan Spieths, Rickie Fowlers, and Michelle Wies have a place to dream big—and weekend warriors have a place to slice and duff—by attending the 19th Hole Party benefiting Lions Municipal Golf Course, an endangered course where the likes of Ben Crenshaw and Tom Kite honed their games.

American Legion, March 24, 6 p.m. the19thholeparty.com

AUSTIN

Forward March

United States congressman John Lewis, who represents the fifth district of Georgia, is a politician who doesn’t simply talk the talk but actually walks the walk, from fighting for civil rights in the sixties to staging demonstrations against Donald Trump in the aughts. To bring his story to a new audience, he collaborated on a three-part series of graphic novels, all titled March, with writer Andrew Aydin and illustrator Nate Powell, both of whom will appear at the University of Texas at Austin with Lewis to talk about the National Book Award–winning series.

Hogg Auditorium, March 24, 10:15 a.m., lbjlibrary.org

COLLEGE STATION

@rt

Brian Piana is an SEO artist, meaning he mines the internet for data, like search words on Twitter for instance, to repurpose as paintings, site-specific installations, and constantly evolving online works, with titles such as The Last 100 Offenders Executed in Texas (Who They Were and What They Said). See pieces by the Texas A&M grad—he earned a Bachelor of Environmental Design, in 1997, and a Master of Science in Visualization Sciences, in 2000—at the exhibit “Blocks,” hosted by his alma mater.

Wright Gallery, March 21 to May 25, one.arch.tamu.edu

HOUSTON

The Long Way Home

Death and even serious illness can be tough topics to broach, but Amarillo native Gail Caldwell, the Pulitzer Prize–winning newspaper critic and author, faced them both with grace and courage in her book Let’s Take the Long Way Home, a memoir about her friendship with fellow writer Caroline Knapp, who died of lung cancer. Hear Caldwell talk about loving someone to the bitter end at the 16th Annual Butterfly Luncheon, benefiting Houston Hospice.

The Houstonian, March 30, 11 a.m., houstonhospice.org

SAN ANTONIO

Free at Last

In 1999 and 2000 four San Antonio women were convicted of a crime that none of them committed—sexual assaulting two little girls—only to be exonerated this past fall. The documentary Southwest of Salem: The Story of the San Antonio Four, screening at the University of Texas at San Antonio on Tuesday, tells the story of the four women, all of whom are gay, and how the movie’s director, Austin filmmaker Deborah Esquenazi, brought light to their case with an interview in which one of the victims, almost twenty years after the fact, recanted her testimony.

University of Texas at San Antonio, March 28, 6 p.m., education.utsa.edu

- More About:

- San Antonio

- Houston

- Fort Worth

- Dallas

- College Station

- Austin