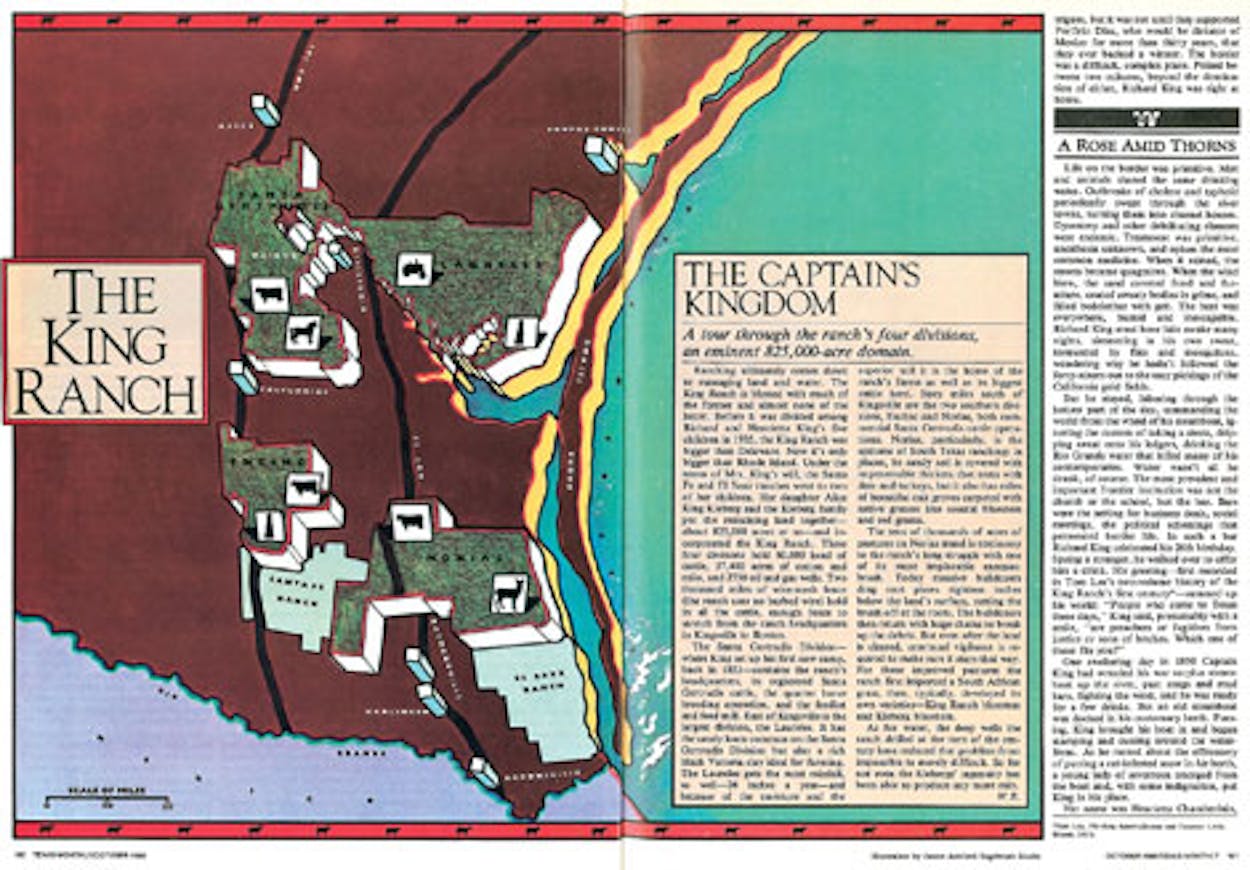

Ranching ultimately comes down to managing land and water. The King Ranch is blessed with much of the former and almost none of the latter. Before it was divided among Richard and Henrietta King’s five children in 1935, the King Ranch was bigger than Delaware. Now it’s only bigger than Rhode Island. Under the terms of Mrs. King’s will, the Santa Fe and El Sauz ranches went to two of her children. Her daughter Alice King Kleberg and the Kleberg family put the remaining land together—about 825,000 acres or so—and incorporated the King Ranch. These four divisions hold 60,000 head of cattle, 37,400 acres of cotton and milo, and 2730 oil and gas wells. Two thousand miles of wire-mesh fence (the ranch uses no barbed wire) hold in all the cattle, enough fence to stretch from the ranch headquarters in Kingsville to Boston.

The Santa Gertrudis Division—where King set up his first cow camp, back in 1853—contains the ranch’s headquarters, its registered Santa Gertrudis cattle, the quarter horse breeding operation, and the feedlot and feed mill. East of Kingsville is the largest division, the Laureles. It has the sandy loam common on the Santa Gertrudis Division but also a rich black Victoria clay ideal for farming. The Laureles gets the most rainfall, as well—26 inches a year—and because of the moisture and the superior soil it is the home of the ranch’s farms as well as its biggest cattle herd. Sixty miles south of Kingsville are the two southern divisions, Encino and Norias, both commercial Santa Gertrudis cattle operations. Norias, particularly, is the epitome of South Texas ranching: in places, its sandy soil is covered with impenetrable thickets that teem with deer and turkeys, but it also has miles of beautiful oak groves carpeted with native grasses like coastal bluestem and red grama.

The tens of thousands of acres of pastures on Norias stand in testimony to the ranch’s long struggle with one of its most implacable enemies: brush. Today massive bulldozers drag root plows eighteen inches below the land’s surface, cutting the brush off at the roots. The bulldozers then return with huge chains to break up the debris. But even after the land is cleared, continual vigilance is required to make sure it stays that way. For these improved pastures the ranch first imported a South African grass, then, typically, developed its own varieties—King Ranch bluestem and Kleberg bluestem.

As for water, the deep wells the ranch drilled at the turn of the century have reduced that problem from impossible to merely difficult. So far not even the Klebergs’ ingenuity has been able to produce any more rain.

- More About:

- King Ranch