It should come as no surprise to learn that Texas has billions and billions, even trillions of cockroaches; after all, at least half of them are in your kitchen. But it may come as something of a shock to learn that even the largest of these does not exceed 34 millimeters in length, or about one and three-eighth inches. Preposterous, you say? Well, that’s the claim of University of Texas paleoentomologist Dr, Christopher Durden, who studies such matters for a living and presumably gets hardship pay for it. Durden concedes that Texas cockroaches often look larger than scientific records show, but there can be no doubt that Texas does not have the largest roaches in the world, or even in the nation. The fact is that roaches in the Florida Keys grow up to an inch longer than any cockroaches found in Texas, and some species in Central America have a six-inch wingspan and measure four inches in length. Scientists say it is safe to say Texas has more cockroaches than any other state, but they cannot tell us how overrun we really are. There is just no effective way to count—or even estimate—cockroaches.

Nevertheless, Austin, our capital city, has gained a wide reputation as a “capital of cockroaches.” Last summer, the Austin Sun, a weekly newspaper well qualified to know, made national news with its claim that a house in Austin holds the world’s record for the most roaches in a single residence: some 50,000. Although this record has not been contested, scientists say there must be many places in Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, and El Paso which exceed that cockroach count. Being both the hottest state in the nation and one of the most urban, Texas is an ideal breeding ground, the incubation center for the entire Southwest and points beyond. Along with air conditioning, the cockroach is found in both our mansions and our slums, an ubiquitous equalizer of all types of humanity.

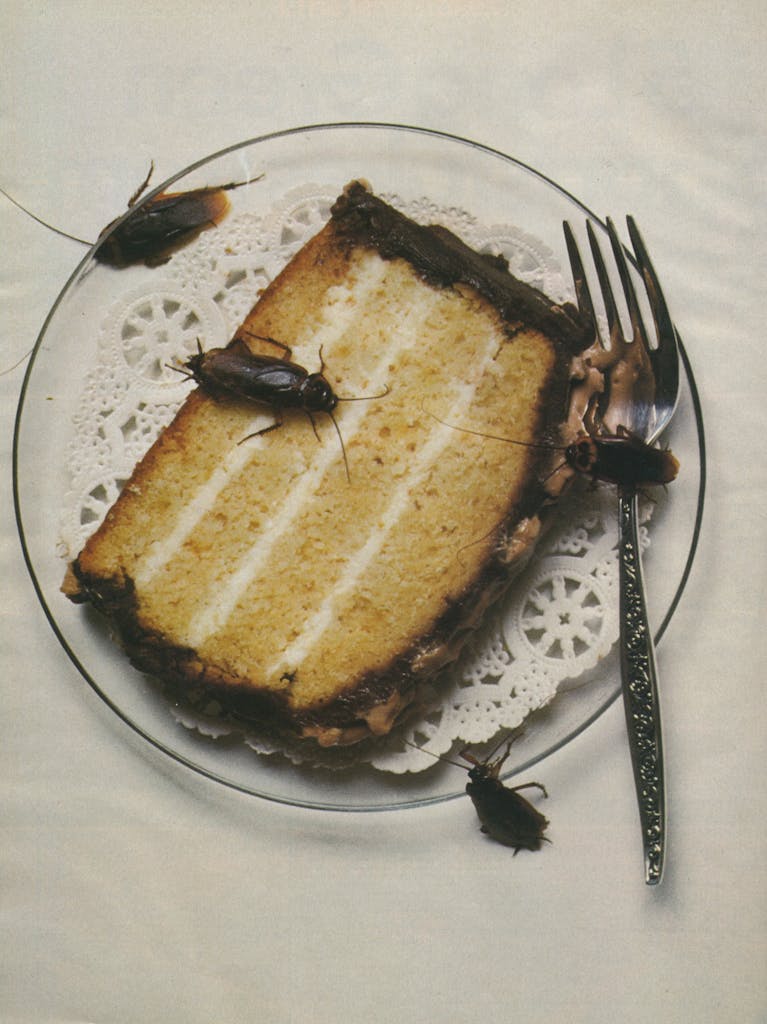

The most curious consequence of this great infestation is that the cockroach is now the state’s most celebrated insect: having won renown as an exceptionally persistent and intimidating household pest, the bug has become camp. College students honor it with annual pageantry and games. Artists immortalize it in paintings, poetry, and song. A Dallas anti-poverty protester uses it as an audiovisual, and UT football coach Darrell Royal uses it to describe an opposing team, and state politicians use it as an epithet. Already there are cockroach comic strips, T-shirts, and embroidered patches. All that remains is for Neiman-Marcus to recognize the potential market in cockroach chic.

Strange as it may seem, such cockroach cubism is not unprecedented. In Finland and in many European countries, the cockroach was once revered as a protector of life and allowed- to live freely in the homes of even the most prominent people. Other cultures, including our own, have used cockroaches for medicinal purposes—-often as a diuretic or

a digestive aid—and even for food.

The Spanish, from whom we get the word “cockroach,” were much more insightful about the bug. They called it cacarucha, later cucaracha, a derivative of their word for excrement. No name could fit better. Despite the occasional claims of roachophiles, the insect is not better than it looks. It does not merely look hideous, it really is dirty, disgusting, and hazardous to human health, capable of communicating nearly a hundred different diseases and unswervingly dedicated to living in, eating, producing, and spreading the substance for which the Spanish named it. What’s more, despite a natural inclination to retreat, the cockroach can quite easily bite—and has even been known to attack—unsuspecting human beings.

Oddly enough, the cockroach does not cause the kind of easily measurable direct damage to plants and property that other insect pests do. To be sure, the cockroach does eat and/or spoil tens of millions of dollars worth of food in Texas each year, but it does not, like its cousin the termite, devour whole rooftops.

Nevertheless, exterminators say that the cockroach is our state’s most complained about insect, and their biggest money-making pest. Much of the reason for this is emotional rather than scientific in nature. “Cockroaches are the insect people are most repulsed by,” observes Texas A&M entomologist Dr. Genaro Lopez. “When you try to put a dollar value on the damage it causes, you’ve got to consider that.” His point is well taken, for who is there who has not experienced the pulse-pounding horror of the Kitchen Light Phenomenon—that stultifying instant when the light goes on and the roaches that reside in one’s kitchen are revealed in their full infestation? The roach’s greatest evil power is this ability to inspire the most intense shock, fear, and embarrassment by virtue of its appearance alone.

As a result, the majority of regular-minded Texans still want simply to kill cockroaches, not revere them, and each year they spend an estimated $200 million to accomplish that end. However, no matter what we do, the cockroach will probably outlast human presence on the planet; besides being able to resist most chemicals, the cockroach has shown an ability to survive massive amounts of radiation, and will thus be a likely candidate to inherit the earth after a nuclear holocaust.

Ironically, recent research by a Virginia biologist suggests that cockroaches may also provide man with some important clues to finding a cure for cancer. Other scientists say cockroaches can even tell us something about our own patterns of social behavior. Superbly suited to Texas, cockroaches live in herds and display a number of “human” characteristics, including tribalism, cannibalism, and maternalism. They have a long and complicated sex life, and they can run, hop, skip, jump, swim, climb, fly, and hang upside down.

All things considered, then, the cockroach is well worthy of the great state with which it has become associated and fully deserving of death. I recently learned much more about the bug—including some interesting, inexpensive, and definitive ways to get rid of it—by going on a roach hunt through Austin. My companions represented two different but deadly areas of insect expertise. One was UT’s Christopher Durden, who specializes in fossil cockroaches; the other was Big Jim Quinn, owner and operator of Greenline Pest Control, an independent Austin-based lawn care and exterminating company. As we killed and collected specimens in slums, sewers, creeks, cracks, restaurants, and riverfront mansions, the two of them explained how cockroaches live, multiply, and die.

Durden began by pointing out that cockroaches are among the world’s oldest terrestrial beings, having come after ferns but before reptiles. Some extinct species, he said, date back more than 320 million years. When cockroaches first appeared, they were confined to the equator, then running through Baja California, Texas, and Newfoundland to Central Europe. Nevertheless, they really had an easy life. The only vertebrates on dry land were salamanderlike amphibians called labyrinthodonts, which were slow and clumsy as their names, terrible at catching cockroaches. However, as the earth got warmer, the reptiles appeared and ate the large cockroaches of the tropics; most of the survivor roaches were ones who already lived in the temperate zones. The overall cockroach population declined, and for a while, the little insects didn’t have it so good.

Then the dinosaurs appeared. Suddenly roaches were blessed with abundant sources of their five most important needs: food, water, warmth, shelter, and, not least, waste. They followed the dinosaurs everywhere, multiplying at a rapid pace once again. However, even the dinosaurs eventually became extinct, and the cockroach population began its second—and last—great decline.

Man saved them. Not since the dinosaurs had cockroaches been so readily provided with a source of their five greatest needs (particularly the fifth). Wisely, the little buggers also followed us everywhere, and they proliferated as never before. Today cockroaches are found in virtually all warm to temperate parts of the world; having accompanied man on all his travels, they are even found indoors in the less preferable climates of Alaska, Siberia, and certain Arctic regions.

Even more disconcerting, cockroaches are bigger today than ever before. “Some books incorrectly suggest that the past was the age of giant cockroaches,” Durden said. “The truth is that they are bigger now than at any time in history.” They have grown fat with civilization.

They have also grown dirtier. Durden explained that the roaches which inhabit the “wild” areas of the world, though capable disease carriers, are generally less infectious than the average insect. However, urban or “domestic” roaches are much more proficient. According to Drs. Louis M. Roth and Edwin R. Willis, authors of the U.S. Army’s definitive compilation of cockroach information, The Biotic Associations of Cockroaches, roaches have been known to carry four different strains of polio virus; typhoid; yellow fever; and nearly a hundred species of bacteria, protozoans, and parasites that can make people sick. (In fairness, however, it should be mentioned that roaches are not, as past reports have wrongfully suggested, guilty of causing beriberi, Bright’s disease, malaria, kala-azar, or scurvy.)

All this becomes even less comforting with the knowledge that cockroaches will attack and bite much larger—and usually sleeping—human adversaries. As one of more than twenty documented examples of such aggression, Roth and Willis report the experience of a Japanese entomologist who discounted the roach’s ability to bite until he awoke one morning to discover cockroaches nibbling on his toes and breast. However, they write that “the injury is usually confined to abrasion of the callused portions of the hands and feet but may result in small wounds in the softer skin of the face and neck.” Big Jim Quinn observed that on many of his exterminating ventures, “You open up a closet and they will all but jump out and try to beat you up. You tell people that and they won’t believe you unless they’ve seen it.” Other scientists say that roaches will suck at human lips when moisture is unavailable elsewhere, and the more brazen ones will eat the eyelashes of sleeping infants. Unfortunately, most of these man-eating roaches belong to a species which is extremely common in Texas—but most of the time their instinct is to run away.

The character of this smell is best discovered by experience for description can only reveal it as an ominous, awful fetid odor which might be approximated to a fecal soy sauce.

Like most long-time cockroach researchers, Durden can identify the species predominant in the room or restaurant simply on the basis of smell. While it may be difficult to persuade the layman to acquire so refined a skill, it is easy enough to detect the undifferentiated odor of roach in heavily infested areas. The character of this smell is best discovered by experience for description can only reveal it as an ominous, awful fetid odor which might be approximated to a fecal soy sauce. It is produced both by the roaches’ waste and by various sexual and functionary secretions. I saw Durden dramatically demonstrate his special training at one of the first houses on our roach hunt. No sooner had he sniffed the air and murmured “Blaitella germanica,” than three tiny roaches scurried across the kitchen sink. After Big Jim zapped them with a burst of pesticide from his double-action spray head hose, we discovered that they were, as he had predicted, typical German cockroaches, the most common species in Texas and many other parts of the world,

A sort of pale, yellowish brown with dark stripes on the front, Blattella germanica is the smallest (length, ½ inch and under), most numerous, and most elusive and destructive cockroach we are bothered with. It is sometimes called the Croton bug because it was once found in New York City’s Croton Waterworks, but it now prefers restaurants and residential kitchens. B. germanica shares the same basic roach design, though slightly more delicate than other species: a flat, streamlined body covered with an oily film; six durable, swept-back legs covered with bristles or “spurs”; heavy jaws with side-to-side pincers; and two hair-like antennae. Like other roaches, B. germanica appears to be sensitive to both light and air currents, and has a built-in alarm system, “cerci organ,” which alerts it to impending danger. “We have reason to believe that the cockroach’s conception of the universe is very different from ours,” Durden said. “They seem to use a wind-pattern equivalent of sonar to get around.” That’s one reason they can get out of the way so fast, seemingly in anticipation of the human reflex. Another way is that 75 per cent of the world’s cockroaches can fly and most can manage in water, but only a small percentage are amphibious. In the species B. germanica, the males can fly but the females cannot; both sexes can swim.

The next most common cockroach in Texas is Penplaneta amencana, the “American” cockroach. These are the man-eating ones. They are big, reddish brown, and generally found in residential kitchens. Capable of growing up to one and three-eighths inches, they are the fifth-largest species in the nation. According to Durden, P. americana also is the second most malodorous. The worst, he says, is Blatta orientalis, the Oriental cockroach, or “black beetle,” but these are not very common in North America. The smell of B. germanica Durden ranks third.

Six of nearly 40 other indigenous species are also common in Texas:

- Periplaneta brunnea—a big reddish brown roach similar to P. americana, which tends to frequent the more humid, coastal areas, such as Brownsville, Corpus Christi, and Houston, but also has been reported in high concentration in the inland city of San Antonio;

- Periplaneta fuliginosa—also about the same size and shape as P. americana, but deep reddish black in color;

- Parcoblatta species—the brown “wood” roaches, the most common of the nonflying cockroaches;

- Ischnoptera deropeltiformis—a small black wild roach of fields;

- Pseudomops septentrionaiis—a pretty little orange-, black-, and cream- bordered wild roach which runs in broad daylight along the banks of Texas and Mexican streams.

- Supella supellectilium—a small brown roach which presents particular extermination problems because of its wide dispersal throughout the house and because it can hang on ceilings; it often fights B. germanica for control of the kitchen.

In addition to these common cockroaches, we may now and then get one of the more exotic types in a food shipment from some other part of the world. The most awesome and ferocious North American species is Blaberus giganteus (length, two and three-eighths inches) of Cuba and the Florida Keys. Though never seen in the Lone Star State, this species is perhaps the closest real-life equivalent of the terrible Texas Cockroach that inhabits the national imagination. Sometimes called “palmetto beetles,” these bugs have long, spiny legs covered with sharp spurs which they will dig into humans and other adversaries; the effect is said to be similar to walking into the thorns of the yucca plant. “Many roaches have spurs, but with Blaberus they’re a weapon,” Durden said. Blaberus also emits a body grease which can cause an allergic reaction when contacted by human skin. Mexico and South America also have species of Blaberus which rival this awful thing, but the fiercest roach of all is the African Gromphadorhina portentosa. Sometimes called “the squeaking roach of Madagascar,” this species is known not only to attack but also to hiss and butt its head while doing so. The world’s largest living cockroach, meanwhile, is the Megaloblatta blaberoides of Central America, which has a wingspan of six and three-quarters inches and an overall body length of almost four inches.

Certain less fearsome but no less interesting varieties also populate the planet. One often found in creek beds is the “sand roach,” species of Arenivaga, which according to Durden, “feels like velvet,” In other parts of the world, there are luminous green roaches and roaches with bright yellow spots. White cockroaches are not albinos but roaches of one of the above species which have shed their old skin and not yet tanned the new skin.

Of the species common in Texas only P. americana has both a “domestic” variety, which lives indoors with man, and a “wild” variety. Most prefer habitats that are warm and moist. The outdoor type frequent all sorts of places, but especially creek beds, hollow logs, damp rocks, wood piles, and tropical ferns. Equally adaptable, the indoor variety prefers kitchens, basements, closets, cabinets, drawers, bathrooms, and locations near warm pipes and electrical wiring. Other less likely places roaches have been found include televisions, telephones, switch boxes, malted milk dispensers, electrical clock cases, loud speaker baffles, cash registers, steam tables, coin-operated vending machines, car radiators, incubators of premature babies, and airplanes.

Roaches are also prevalent on ships, especially banana boats. Among the earliest to record their presence aboard ship was the notorious Captain Bligh of the HMS Bounty, who logged a description of disinfecting his soon to be mutinied ship with hot water to kill the cockroaches. When scientists examined the sunken Spanish galleon whose treasure became a source of controversy in the late Sixties they found roach fossils in the ship’s hold. One species of cockroach, B. orientals, en route from the Old World to the New World, and one, P. americana, on its way from the New World to the Old.

It will probably come as little surprise to the homeowner that cockroaches live in “herds.” These herds are not, however, the mass cockroach rallies one might imagine, but groups of about 20 or 30 individuals. Larger groups, scientists say, are not stable and tend to break up. This does not mean that the cockroaches will go away or that no more than 30 are ever together at one time and place, just that they’ll occupy the sink in organized cliques rather than as an undifferentiated swarm. A single herd may consist of one or several species. At certain times, the members will be gregarious, drawn together by a need for warmth and by (to them) pleasant body secretions. On other occasions, however, the herd will fight other herds or herd members will fight each other. Often the intra-herd battles will take the form of generational warfare, with young and old vying for the choicest territory. These attacks range from raising and lowering the wings to charging, bumping, and biting. Confirmed cannibals, roaches are not above eating one another at the end of such skirmishes.

Cockroaches also fight a great deal about sex. Males fight other males, and females fight males. Drs. Roth and Willis write of one experiment in which “one female was especially vicious and attacked each new male as he was introduced into the container.” Some of the reasons for this sexual aggression have to do with the fact that the sex act itself is long and complicated. It begins as a putridly perfumed dance. The partners secrete a pheromone—roughly equivalent to a hormone with a smell—which acts as a sexual attractant and can be perceived from several feet away. If their pheromones are enticing, the partners will start fencing head to head. Then the male will turn, raise his wings, and try to back in under the female. Then comes the tricky part. The partners must grasp each other—her mouth to his abdominal scent glands—and twist out at 180 degrees, a move which leaves them end to end and facing in opposite directions. This intricacy is necessary for things to fit. The roaches will then remain so positioned for one to three hours; this is one of the longest insect copulations, but not, as has been previously reported the longest: some butterflies do it for 36 hours at a time.

Sadly, there is no season for cockroaches: they mate year round. The typical incubation period may range from a few days in warm weather to all winter, and there is no limit to the number of eggs a female can lay. The adolescence and longevity of cockroaches also vary among species, but most roaches reach adulthood in a few weeks and those who escape human wrath enjoy a total life span of about one year.

In cockroach herds, there is a more equal division of labor than is the case with bees, but, as in human communities, the female usually takes care of the young. While the eggs of some species hatch with virtually no female attention, most species display a profound maternal ism from the time sex is over until well after offspring hatch. Some females carry their unhatched eggs in brood sacs held under their bodies. Others carry young under their wings. Still others will spend an hour or so excavating a hole for their eggs which they then close with a thick oral secretion and cover with trash. In some species, the females are parthenogenic, and can thus reproduce other females without fertilization by a male.

Not too surprisingly, roaches will eat just about anything. As Drs. Roth and Willis write, “It is almost impossible, despite good housekeeping, to keep any structure used by man free of all food suitable for cockroaches.” The always popular cockroach dishes are rotten fruits and vegetables, sweets, and starches. Some of the more exotic dishes they enjoy include paper, ink, glue, wood, roses, geraniums, orchids, and palms, as welt as ants, wasps, crickets, termites, and centipedes. When water and/or any of these things are readily accessible in the kitchen or any other part of the house, roaches will surely appear.

Most surprising is that man will eat cockroaches. Roth and Willis list half a dozen scientists and observers who report that roaches have been used for food by people in Australia, Japan, China, Thailand, Guinea, and even England and Ireland. For example, while traveling in the South Atlantic in the late 1820s, W. H. B. Webster of HM Sloop Chanticleer wrote that “common salt and water saturated with the juices of the cockroach had all the odor and some of the flavor and qualities of soy.” One German doctor claimed in 1911 that “shelled” cockroaches taste like shrimp. And as late as 1946, a French student traveling in Guinea observed the commandant of the French colonial army happily eating raw cockroaches with members of the Kissi tribe. Roth and Willis also provide the following recipe, vintage 1905, which was reportedly eaten by Irishmen and “Englishmen in London”; “A succulent dish is made from cockroaches simmered in vinegar all morning and then dried in the sun. The insects, freed of heads and intestines, are then boiled together with butter, farina, pepper, and salt to make a paste which is spread on buttered bread.”

Roth and Willis also provide a longer list of instances in which cockroaches have been used as medicine, though they carefully point out that most roach-made remedies are “highly questionable” in value and “based almost entirely on pristine beliefs and popular fallacies.” Surprisingly, the remedies with the greatest number of favorable reports are the uses of cockroaches as a diuretic and as a digestive aid. In fact, Roth and Willis give a whole series of accounts from England, Europe, Asia, and even America, which describe roaches as a kind of nineteenth-century TUMS. In November 1944 the New York Times reported that a concoction of red cockroaches and liquor was one of the most commonly used remedies during an influenza epidemic in Iquitos, Peru. Other ills cockroaches have been credited with curing include boils, spasms, tetanus, earache, ulcers, warts, whooping cough, tumors, tuberculosis, heart disease, sting ray injuries, pleurisy, itching, and cirrhosis of the liver.

But if all the above uses of cockroaches are mostly old wives’ tales, modern science is now finding that cockroaches may have some medical value, after all. Peter C. Sherertz, a Virginia Commonwealth University biologist has discovered that P. americana, the common household cockroach, can ingest a powerful cancer-causing agent without suffering any harmful effect; he is hopeful that studying the way cockroaches combat cancer might provide some clues for man. Nevertheless, optimism should be restrained by the fact that the ability in one organism to detoxify a substance is not necessarily the case in another organism, and readers would be ill-advised to ingest cockroaches in the hopes they will thus be protected against cancer.

Long before the most recent news of its cancer research potential, the cockroach was the world’s most celebrated bug. Some cultures even regard it as a protector of life—in Finland, for example, superstition held that they should not be killed, especially not by burning—but cockroaches are far more likely to be viewed as profane than as sacred. One of the first things Captain John Smith wrote about on arriving in Virginia was “a certaine India Bug called by the Spaniards a Cacarootch, the which creeping into Chests they eat and defile with their ill-sented dung.” In Mexico, the cockroach took on quite another aspect of the profane as the symbol for the 1912-1916 revolution. The revolutionaries immortalized the insect, their cause, and marijuana in the song “La Cucaracha”, whose first verse goes:

The cockroach, the cockroach

Doesn’t want to travel on

Because it’s wanting,

Because it’s needing

Marijuana for a smoke.

Wanda Willson Whitman writes in Songs that Changed the World, “A cockroach seemed the perfect symbol for the raids by Pancho Villa, whose followers disappeared into the night or into canyons south of the border as the kitchen pest seems to vanish into thin air. Also appropriate, as the revolution spread, was the rapid proliferation of cockroaches. As for marijuana, that too would cross the border in time.” Presumably, this is the origin of the term “roach” for a burned marijuana cigarette, though as Hunter S. Thompson has written, “You’d have to be crazy on acid to think a joint looked like a goddamn cockroach.”

In the Thirties, Don Marquis began what might be called the literary-symbolic suburbanization of the cockroach with the publication of Archy and Mehitabel, a series of poems supposedly written by a cockroach who had been a human in a previous incarnation. In one of them Archy says:

i was once a vers libre bard

but i died and my soul went

into the body of a cockroach

it has given me a new outlook

upon life

i see things from

the underside now

Cartoonist Gilbert Shelton was one of the first Texans to mythologize the terrible Texas Cockroach. While a student at the University of Texas at Austin during the Sixties, Shelton began “The Adventures of those Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers” in the student humor magazine, the Texas Ranger, among the main nonhuman characters were Fat Freddy’s Cat and the amazing Texas Cockroach, a creature complete with Stetson, boots, and spurs, who could flip his much larger feline opponent judo-style. Later, Shelton moved to San Francisco, and became part of the scene, but Rip Off Press still publishes his work in Freak Brothers comic books, and his Texas Cockroach still outwits Fat Freddy’s Cat.

Another UT figure gained wide publicity for using the cockroach as a symbol. When a mediocre TCU football team upset his Longhorns in 1961, denying them a national championship, Darrell Royal looked for a metaphor in the agony of defeat and could find none more apt than the bane of the insect world. “They’re like cockroaches,” he said of TCU. “It’s not what they carry away that kills you; it’s what they fall into and mess up.”

Lately, however, the cockroach has become less a symbol for the hip movement and more a symbol of good old-fashioned college fun. Students at UT-Austin and Rice University now hold annual spring festivals which honor the cockroach with pageantry, feasting, and games. The residents of UT’s Simkins dormitory have had a roach—or, more precisely, a giant emblem of a roach—as their mascot for nearly five years. The dorm adopted the insectile symbol to protest housing conditions to the Administration; the symbol stuck, but gradually lost its political significance: now it represents a kind of dorm spirit of hedonism and fun. Residents there sport T-shirts and jerseys emblazoned with the roach emblem and the letters S.H.I.T.—initials which denote both “Simkins Hall Intramural Team” and the living conditions students share with cockroaches. This year the students put on the first annual “Miss Roach Contest”-—with real people, not real roaches. The winner out of 39 female entries was Sylvia Salinas, a dark-haired native of Austin, the state’s “cockroach capital.” Asked after the pageant if she herself feared cockroaches, Ms. Salinas answered, “Not the ones who live in Simkins Hall.”

Students at Rice, however, have gone one better, or, if you prefer, one worse. This year Baker College held its second annual Baker Cockroach Races—with real roaches. Among the things these poor students did was pour cockroaches out of a glass jar and time their progress to the center of a seven-foot circle. The winner was proclaimed “fastest roach.” Other prizes went to the “best decorated” and the “biggest.”

Politicians are even in on the cockroach revival. During one of the battles over the ill-fated constitutional revision effort in the spring of 1975, Convention President Price Daniel, Jr., labeled political opponents of reform “cockroaches.” The next day, doggerel about roaches was circulating through the Capitol. The press picked up the story, and the politicians Daniel had slurred began wearing lapel buttons picturing a cockroach.

In March, Charlie Young, a Dallas antipoverty protester, went still further. Convinced that the Dallas City Council was turning a deaf ear to the housing problems of the city’s east side, he turned his back on the council and released a boxful of cockroaches right in the council chamber. Orders were given to eject both Young and the roaches; Young departed but some roaches remain.

Dallas artist George Green has now added a series of oil paintings to Texas cockroach culture. Intended to portray some of the human qualities of cockroaches and the cockroach qualities of humans, the paintings range from “The Sex Life of Cockroaches” to “Cockroach Hairstyles.”

Fortunately, at least as much creative energy has been devoted to killing cockroaches. One lakeside resident, for example, used to shoot them with a revolver. Of course, methods like that can really wreck a place, so with the help of Big Jim Quinn, Dr. Durden, and other pest control experts, I compiled the following list of five more efficient ways:

The first and most expensive method of killing cockroaches is to hire a professional exterminator. According to the Structural Pest Control Board (SPCB), the state agency which regulates the exterminating business, about half the pest control companies in the state are individual or family operations which gross up to $25,000 annually. Only a few are large corporations like Orkin and Terminix which gross up to and over $1 million in Texas each year.

Many pest control operators refuse to give an average per-house figure for their services because they say infestation conditions can vary greatly from place to place. Nevertheless, SPCB director Charles Chapman says that a reasonable ball-park figure for a two-bedroom house is roughly $20 to $30. This figure is for cockroach killing only; an antitermite job may cost $150 to $300. Chapman and other SPCB members caution against exterminating services advertised for $5 to $6: to keep his price that low an operator must skimp on time, chemicals, or both. Other types of hustlers also crop up from time to time. “The main trick is the door-to-door technique,” says Dr. Genaro Lopez of Texas A&M and the SPCB. “They drive up and tell you they’ve just finished a neighbor’s house and that they just happen to have some chemicals left in their tank. They’ll quote you a price of five or six dollars but once they get their foot in the door, they pressure you for a termite job and other services. The big thing is roofing and repair work. They’ll say termites are eating your roof and that you need a new one. They’ll also say they know someone who can do that for you. They particularly like to prey on old people.” Dr. Lopez and other board members say the best way the consumer can guard against such tactics is to ask exterminators to show their license or their SPCB identification card, both of which will have the operator’s registered number.

The chemicals cockroach killers use vary from company to company, but the three main ones are diazinon, baygon, and dursban, all of which are approved by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Chlordane used to be very popular because it can kill roaches and almost every other common household pest, but the EPA has banned chlordane because a series of highly disputed test results indicate the chemical may cause cancer. Both pest control operators and environmentally conscious scientists grumble that the EPA’s ultimatum was political and not scientific in origin. Whatever the case, the label found on chemical containers is now the law, and both pest control operators and the general public are now simply required to follow the printed directions. Since the EPA has also said that long-lasting residual chemicals may not be used indoors, the effectiveness of a good pest control job should not last more than three or four months. Consequently, an efficient modem pest control program now involves two stages: an initial “clean-out” stage characterized by heavy spraying, and regular touch-up jobs every ten or twelve weeks. The downside to extermination is that the bugs can develop strains that will resist the chemicals; they will also hide until the chemical wears off. Another drawback is the inconvenience exterminating causes for the human occupants.

A simple, inexpensive, and very effective alternative is boric acid. Dr. Durden suggests mixing the boric acid with some edible white substance like flour, pouring the concoction into bottle caps, and placing these at strategic locations around the kitchen. Mix well, or the roaches will separate the goodies from the poison. Do it properly and you will knock them dead. The disadvantage to this method is that boric acid is toxic; if consumed, it can be fatal, depending on amount ingested and subsequent treatment. Bottle caps filled with the stuff should be kept well out of the reach of children.

A more complicated method of killing cockroaches is by collecting and keeping insects and animals that kill them. This is the ecosystems approach. Among the most effective cockroach killers are spiders, scorpions, owls, wasps, praying mantids, toads, tree frogs, hedgehogs, lizards, rats, sparrows, foxes, mongeese, and cats. Chickens are also renowned cockroach killers as proclaimed in the Spanish proverb: “The cockroach is always wrong when arguing with the chicken.” The problem with this method, in addition to its delicacy and complexity, is the fact that numerous of the above cockroach killers are deserving of death themselves.

Two other potentially revolutionary methods of killing cockroaches are now slated for research. One involves the apples of the bois d’arc, sometimes called osage oranges. These are green fruit about five inches in diameter, which are poisonous to both humans and cockroaches. Popular reports have it that if the fruit is punctured and placed in cabinets and closets, the smell will actually drive roaches away. University of Texas at Austin cockroach researchers plan to do some experiments with the bois d’arc apple soon. Meanwhile, researchers at Texas A&M are exploring an even more exotic way of death: the use of roach pheromones to lure the cockroaches into traps.

Of course, no matter how easy science may one day make it to kill cockroaches, it is doubtful the insects will ever lose their ability to intimidate many people simply by their appearance. The story of a young Austin woman illustrates the worst of these fears realized. “One night I kept having these dreams about something crawling all over me,” she recalled in a recent interview. “It was really horrible! I felt it go all over my face, my eyes, my mouth, even into my nose. Then I woke up. I looked down, and there, perched right between my preteen breasts, was a giant cockroach—nibbling! God! I had to spend eight months with a shrink after that. I don’t think I’ll ever get over it.”

While few people have experiences quite so extreme, the intense emotions cockroaches evoke will probably insure the continued popularity of a sixth method of killing them—the old-fashioned foot-stomping technique. The difficulty with this method is that roaches, being faster than the human reflex, can often get out of the way. However, no other method allows one the satisfaction of hearing the exquisite crunch cockroaches make when they are crushed beneath a heavy shoe.