The Urban Wilderness Hike

Franklin Mountains State Park

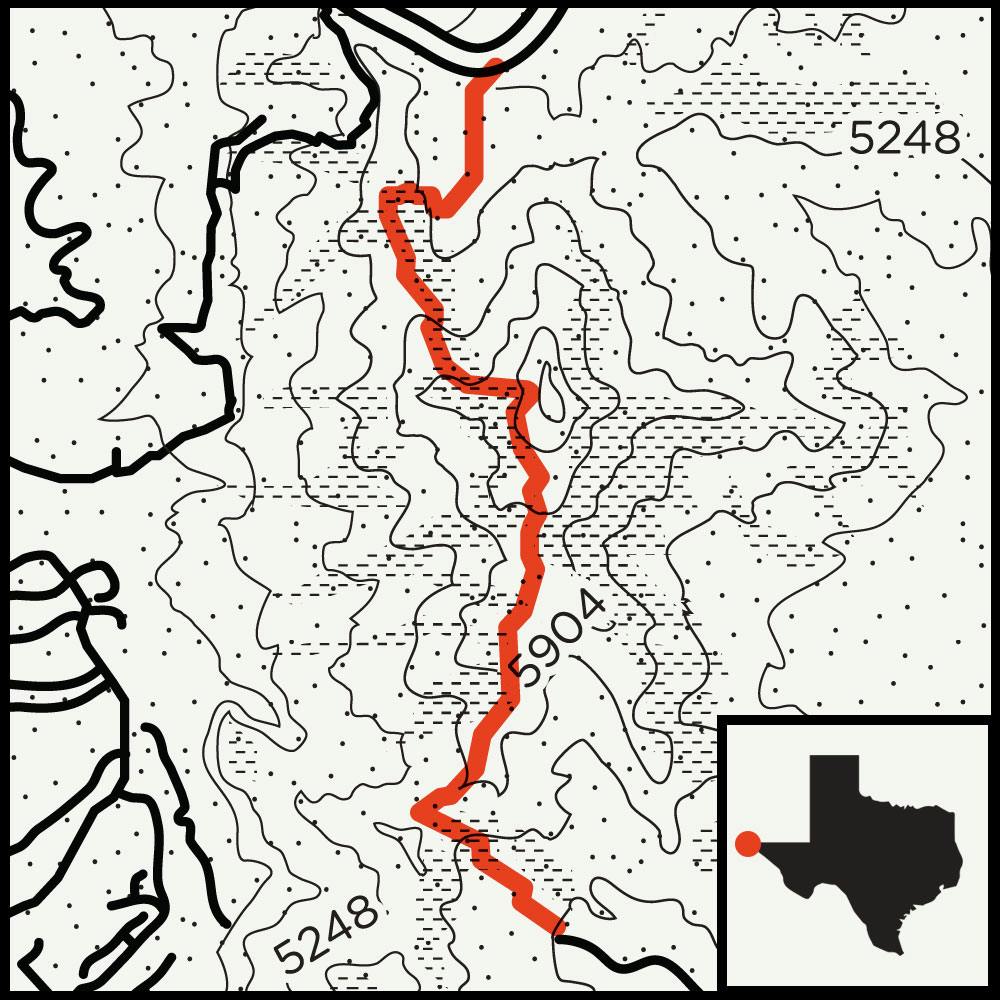

Route: Ron Coleman Trail

Distance: 3.5 miles

Difficulty: Hard. Be prepared for some steep and semi-technical sections; chains are affixed to the trail for safety.

The most difficult stretch of trail I hiked last year was all downhill.

The most difficult stretch of trail I hiked last year was all downhill.

Because previous trips to South Franklin Mountain had proved that the 6,700-foot peak, which rises like a titanic battlement above El Paso, could dish out punishment, I originally mapped out what I thought would be a fairly easy hike. I planned to take my daughter and wife over the mountain southbound via the Ron Coleman Trail. I knew it was steep but also just a few miles long. My main concern centered on the trail’s starting point, which sits in a dodgy cut of road known as Smuggler’s Pass—so named for its past use as a criminal hideout—and how we might get back after the hike.

But my daughter balked at the trail before we even started, and my wife, of course, sided with the kiddo. So as they retreated to the car, I set off on the trail and huffed my way up 1,500 feet, dusting several teens who marched to tinny tunes coming from the speakers on their phones. In time, I remembered why I came: I had the nation’s largest urban wilderness to myself. I took in the astonishing cliff-top views, with the Rio Grande splitting the United States from Mexico, and New Mexico stretching along the curve of the earth toward the northwest horizon. Borders disappear at this elevation.

However, that serenity disappeared when I somehow lost the trail markers in the shadow of the several towers that occupy the peak. After thirty minutes of wandering around, I finally retraced my steps back to the trail, followed it to the other side of the mountain, and began my descent.

I sweated and struggled the entire way down, desperately holding on to the chains affixed to the trail-side cliffs for safety. I only later learned that most people travel northbound across the mountain on this set of trails; apparently the chains are more helpful heading uphill. By the time I reached bottom, I had no regrets that my family had bided their time by driving to meet me on the other side and were waiting for me from the comfort of our car.

The Mountain Wilderness Hike

Guadalupe Mountains National Park

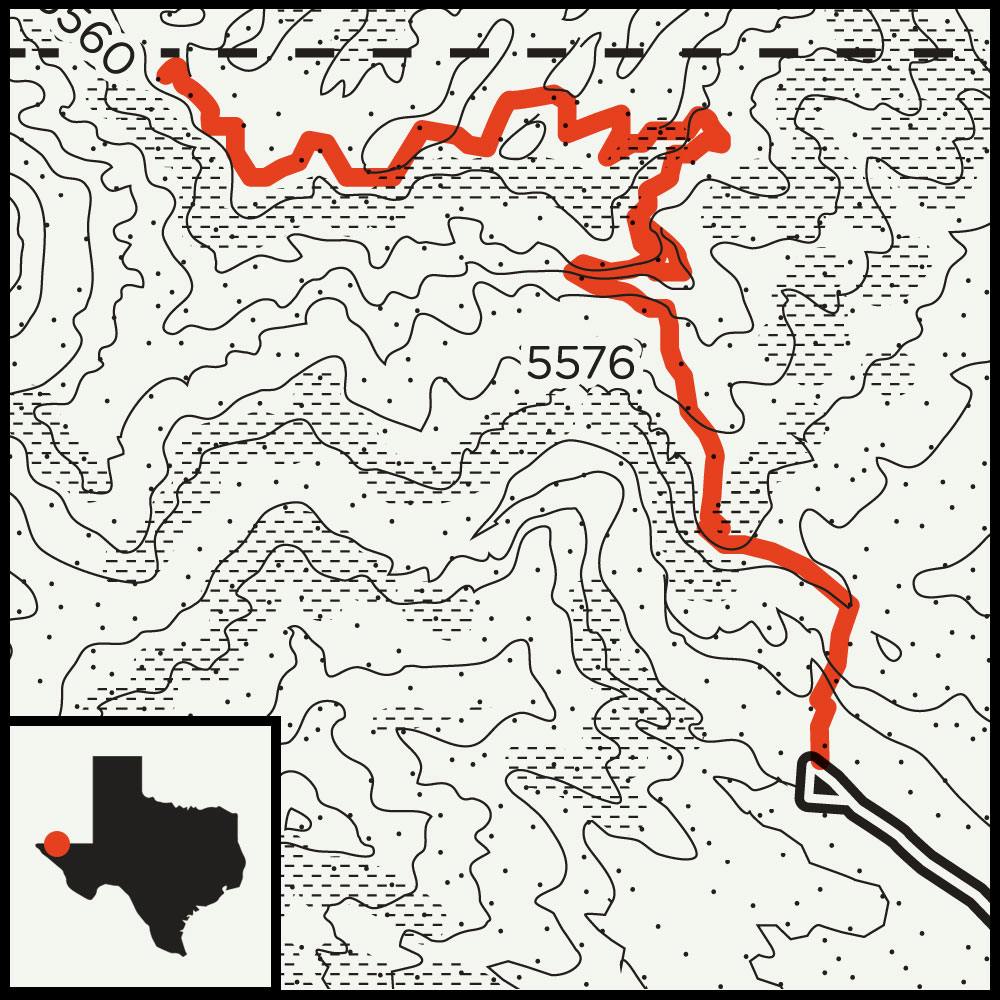

Route: Permian Reef Geology Trail

Distance: 8.5 miles (round-trip)

Difficulty: Hard. The full hike to Wilderness Ridge is not for tenderfoots, and getting to the far reaches of the trail requires a 2,000-foot climb over exposed terrain.

The promise of reaching the highest point in Texas—8,751 feet above sea level—attracts most visitors to the Guadalupe Mountains, which sit about one hundred miles east of El Paso and square in the middle of nowhere. But given the national park’s vast mountain wilderness, from low-lying white gypsum dunes to maple-lined trout streams, climbing Guadalupe Peak doesn’t need to be at the top of your agenda. I took that approach on my most recent trip to the park and set my sights instead on an isolated spot known as Wilderness Ridge, where the mountains level off to the expansive Lincoln National Forest, just on the other side of the New Mexico border.

The promise of reaching the highest point in Texas—8,751 feet above sea level—attracts most visitors to the Guadalupe Mountains, which sit about one hundred miles east of El Paso and square in the middle of nowhere. But given the national park’s vast mountain wilderness, from low-lying white gypsum dunes to maple-lined trout streams, climbing Guadalupe Peak doesn’t need to be at the top of your agenda. I took that approach on my most recent trip to the park and set my sights instead on an isolated spot known as Wilderness Ridge, where the mountains level off to the expansive Lincoln National Forest, just on the other side of the New Mexico border.

I had invited two friends for the trip, hoping to cultivate future backpacking partners, and we drove up a service road in the northeast corner of the park until we reached the trailhead to the four-mile Permian Reef Geology Trail, an intimidating, unprotected traverse that leads to Wilderness Ridge. We set off on the trail and skirted exposed fossil beds, remnants of the range’s former position at the bottom of the ocean, and then climbed past a series of daunting cliffs, where I fell behind. I followed a skinny trail, a peregrine falcon soaring overhead, until the thousand-foot drops turned to a rolling path through the pines and I reunited with my partners.

When we finally reached a spot to make camp, we recalibrated with a hot meal and a flask of whiskey and enjoyed an almost otherworldly sunset from an elevation of around 6,800 feet, perched on a plateau overlooking the McKittrick Canyon that stretched to the south and the forests of New Mexico that spread to the north. It wasn’t the highest point in the park, but we were giddy from the elevation. If that doesn’t count as a peak experience, I have no idea what does.

The Most-Epic-Big-Bend-Desert-Adventure-You’ll-Ever-Experience Hike

Big Bend National Park

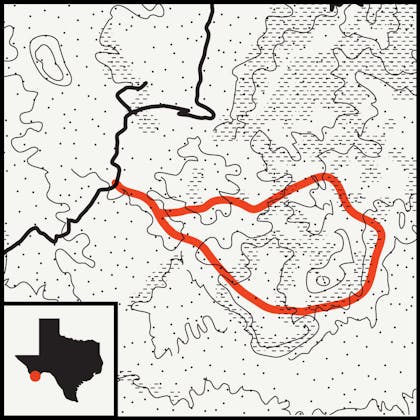

Route: Mostly unmarked trails past Mule Ear Peaks and around the Sierra Quemada to Smokey Creek Trail

Distance: 27 miles

Difficulty: Extreme. This trip calls for physical fitness and previous backcountry experience. Potential hazards include canyon descents, extreme desert heat, and miles of unmarked trail.

Three friends stood just north of Mule Ear Peaks, a sentinel-like formation near the belly of Big Bend National Park. We had reached the spot from an access point along Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive, about midway between the Chisos Basin and the Rio Grande, crossing an expanse of orangish rocks and tumbled boulders that led the way to ancient lava beds. Far to the west, a gunsight notch beckoned above a hidden ravine on the edge of the Sierra Quemada, where we hoped to find a place to pitch our tents two nights hence and refill our water at Dominguez Spring. It would be the backcountry at its finest, but we had our work cut out for us. We would soon cross a lonely arroyo, and there would be no more trails to follow.

Our grizzled trio had come in search of a true wilderness challenge, something grander, sweatier, and more daunting than just another walk in the park. Big Bend has been an escape for generations of Texans who want to get lost, yet as a frequent visitor—I’ve hit Big Bend at least once a year during my two decades in Texas—I’ve noticed it’s gotten a little more crowded lately. Last year, about 440,000 people visited, a record number for the park. During busy periods, in the spring and fall, the wait for a table at the restaurant next to the Chisos Lodge can rival anything Dallas or Houston has to offer, and it’s near impossible to get a room at the lodge itself without securing a reservation far in advance. There’s even steady competition for many of the lesser-known roadside campsites.

Survival Tip

Don’t wait until you’re thirsty to drink. Aim for a gallon of water a day, and save the twelve-ounce cans for the end of the trail.

But in the far reaches of the park, there’s always new and uncharted territory to tackle. You just need to search a little harder and walk a little farther to encounter that rare, reckless solitude. My idea to hike beyond the Mule Ears and into the desert first came about when I stumbled upon an online message board that detailed a bushwhacker’s approach to the lava fields of the remote Sierra Quemada, and I recognized a fresh challenge that would involve more than simply bidding adiós to the park’s best-known trails. We would also bypass any and all official footpaths for about half of the 27-mile hike.

The notion of navigating an unmarked route invited a raised eyebrow from the ranger at the Panther Junction Visitor Center as we picked up our backcountry permits, late last February. In fact, after the ranger learned I would be writing about the journey, she took me aside by the elbow and made me promise that I would make clear that this was a rather radical plan. “In the last couple of years, we’ve not only seen a record number of visitors but also a record number of rescues,” she reminded us, adding that we would not have been allowed to take our trip a week earlier, when temperatures threatened to cross into the triple digits across the desert, during an unseasonable heat wave. She also firmly suggested that we delay our departure a day so we wouldn’t face a forecast storm. That night, as rain laced our tents from the safety of a more developed campsite in Pine Canyon, I sent her my silent thanks.

Given these circumstances, an obvious question for some people would be why an ordinary family man would set out on such an endeavor when Big Bend offers easier hikes with superior views, not to mention plenty of rare birds and lovely woodlands in the shady mountains. For me, the answer lay in the craving for something beyond a simple change of pace, an experience that might shake awake the primitive core of my technology-dimmed mind. If my companions and I succeeded, roaming across sketchy slopes dotted with shin-daggers and searching for cairns across washes where cottonwoods and Mexican buckeye thrive in seemingly impossible conditions, we stood a chance of touching something divine. That may seem far-out, but we were well on our way by the end of first day. The gunsight notch remained in the distance, but the trail was behind us. We made camp by an old stone corral and watched the wheeling stars go by.

Survival Tip

You can always find your bearings with a stick and a little help from the sun. Place the stick upright in the ground and mark the tip of the shadow. Wait fifteen minutes and mark the shadow again. The line between the two points represents a rough east-west axis.

Near the middle of our second day, we made a sweaty ascent up a jagged chasm bisected by a fallen fence that at some point during the past century had likely kept livestock from disappearing into the wild. My companions were Pat, an old college buddy, and Perry, an Austin-based friend. We each carried about thirty pounds of gear, plus food and water. Pat had a satellite compass and altimeter, and I carried a topographic map. We had passed a dozen miles since the last trail marker, which was only a camouflage bandanna tied to an ocotillo branch.

“Do what you need to be your best,” Pat barked after a break on the ridge. If the slope up had been a grind, the descent was something entirely more hellish. I tried the old skier’s trick of adjusting my view of the slope by tilting my head, searching for landing pads where crumbling rock would not sail me into the punishing spiked cholla, saw-leaved sotol, and spiny agave. Perry struggled to stay upright until Pat lent him a trekking pole and helped him pick a safe line down the brutal decline.

We finally pushed beyond the gunsight notch and reached the Sierra Quemada, a name that roughly translates to “burned mountains,” a nod to the naked appearance of the serrated formation. Crossing such a barren and alien corner of the desert range—surely one of the loneliest spots in the Lower 48—causes the mind to pick up tiny, unbidden details: a glistening insect molt suspended on acacia thorns or the whistle of a birdsong from unseen springs. By our third day, after camping near Dominguez Spring, I ceased trying to find proper labels for anything.

It’s a style of surrender I learned by reading the late writer Jim Harrison, whose meditations on wild landscapes and romantic gestures helped make him a best-selling author. In his novella The Beige Dolorosa, a disgraced college professor smashes his watch while working on an Arizona ranch and then begins giving the birds new names. “The thrasher is now called the ‘beige dolorosa,’ ” writes Harrison, “which is reminiscent of a musical phrase in Mozart, one that makes your heart pulse with mystery, as does the bird.”

Deep into our fourth day, we came upon the first hints of a return trail, but the road home would require negotiating a few final precarious turns. A number of the lower paths led to washed-out slot canyons, a descent that would be best attempted with ropes, which we didn’t have. Taking the high road would send us climbing toward the outer loop of the Chisos Mountains, adding several more hours of hiking, which, thanks to the retreating daylight, we didn’t have, either. We decided to take our chances with the lower route.

But once we successfully completed our slow trip down, the trail began to reform beneath our feet. We looked up and marveled again at the Sierra Quemada. Having conquered nearly thirty miles and climbed over four thousand feet, we had been transformed into serious desert dogs. On steely legs, we strode at last onto the pavement, feeling triumphant and fully recharged by the electricity of the eternal.

The Peak Bagger’s Hike

Davis Mountains Preserve

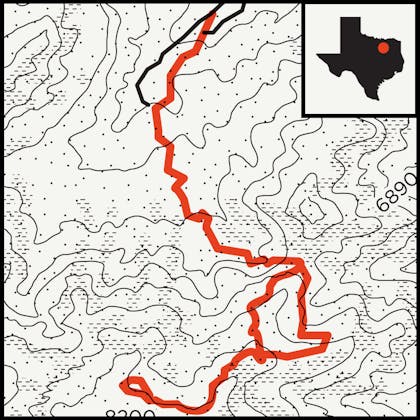

Route: Livermore Summit to Limpia Chute Trail

Distance: 6 miles (round-trip)

Difficulty: Hard. A rough jeep trail gets you close to the summit, but the hike is a grind. Loose gravel on the descent trail makes for a tricky trip down.

The Davis Mountains, the second-highest range in Texas, occupy the northern edge of the Big Bend region. But the prevalence of ponderosa pines and aspen groves makes the Davis Mountains Preserve feel a world apart from the rocky desert landscapes of the more famous national park that sits a little more than a hundred miles to the south.

Mount Livermore, the tallest in the range, tops out with a stony haystack at 8,378 feet, making it an enticing trip for peak baggers like myself. Access can be tricky, though; surrounding ranchers don’t cotton to hordes of shaggy out-of-town dirt nappers disturbing their livestock. But the Nature Conservancy, a nonprofit that manages the preserve, offers access to the 33,000-acre property, including Mount Livermore, about half a dozen times a year. (The open dates are posted on the Nature Conservancy’s website.) During last year’s spring break, my family decided to take advantage of one of the open weekends.

After camping in a quiet corner of the park, my daughter and I made our way to the Livermore trailhead. We attacked the Nature Conservancy’s recommended route to the summit, following a treacherously steep jeep trail that shoots up nearly two thousand feet in just three miles. After a dicey scramble to the top, my vertigo kicked in—the sense of space was so exhilarating I worried that gravity might lose its grip. But we left the summit flush with a sense of accomplishment. After my knees stopped shaking, we started making our way down the other side of the mountain along the Limpia Chute Trail. And just when I thought we were in the clear, my daughter suddenly leaped at me to avoid a reddish coachwhip snake streaking toward the underbrush. “Know your limit” is a frequent caution on challenging trails like these. Now we knew ours.

More Hikes

Short-Timers

These great hikes are far from an all-day affair. Fate Bell Shelter, 1 mile Seminole Canyon State Park You’ll need to schedule in advance, but the park offers guided tours of the cave paintings left behind by some of the earliest residents of this region. West Rim Overlook, 2.5 miles Big Bend Ranch State Park Dozens of trails across this remote state park offer a multitude of ways to experience the other side of Big Bend, but few routes promise the rugged grandeur like this quick out-and-back with astounding views of the Fresno Canyon formation.

No Camping Required

You don’t always need to sleep outdoors for an overnight near the trail. Lost Mine Trail Big Bend National Park The views from this nearly five-mile trail stretch into Mexico, and the trailhead is just a short drive from the Chisos Mountains Lodge. For even more, check out hikes in North Texas, South & Central Texas, and East Texas.