This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

In the gloomy predawn hours of October 6, reveille blasted through the darkened barracks of the Marine Military Academy in Harlingen and blared through overhead speakers, its rapid-fire succession of notes ricocheting off the cinder-block walls and rousing sleeping cadets from their racks. But on that particular fall morning, the cadets of Bravo Company were already awake, many lying wide-eyed in the dark. They had been jolted from their sleep not by reveille but by the panicked cries of eighteen-year-old Cadet Lance Corporal Gabriel Cortez, who had screamed and stumbled out of bed at a few moments after 0300 hours, holding his hand against his neck as footsteps rushed away and down the hall into the darkness. Along his neck, a fresh gash snaked from his right jaw down to the base of his throat, trailing off as it climbed halfway up the other side. Cadets had poured out of their rooms, and a frantic search of the barracks had ensued while Cortez sat in a chair, pale and trembling, his T-shirt covered in blood. Company commanders switched on lights until the barracks blazed in the nighttime, and the cadets were called out on line, standing at attention until everyone was accounted for. Harlingen police officers arrived and searched cadets’ rooms, peering into wall lockers and rifling through belongings; they left before reveille, having made no arrests but promising to return later that day.

By first mess, as the sun started to break over the barracks, rumors circulated that Cortez, who had been taken away in an ambulance, was dying or dead. Cadets sat in the mess hall, looking uneasily at each other over their syrupy pancakes and scrambled eggs. “There were a lot of cold, distant stares,” says Cadet First Sergeant Frank Walker of Echo Company, “because it could have been any one of us.” Cortez hadn’t seen his attackers’ faces in the dark, just fleeing shadows, and the cadets knew that whoever had tried to slit his throat lay in their midst. They went through the motions of their day with a growing sense of apprehension as that morning, and then that afternoon, and then that evening, brought no arrests. “We all thought we knew each other real well,” says Cadet Major Eliel Hinojosa of Echo Company, “but there was a part of each other we just weren’t sure about anymore.” As dusk fell over the academy, it became clear that the cadets who had attacked Cortez would remain among the corps for another night. A deepening anxiety settled over Bravo Company, where cadets found strength in numbers, some sleeping four or five to a 15- by 20-foot room.

After lights-out, a handful of high-ranking cadets decided to take matters into their own hands. They sent for seventeen-year-old Cadet Corporal Christopher Boze, an oddball widely disliked in the corps, who was told to report to the study room. There he found his roommate, Cadet Corporal Jeremy Jensen, standing before a group of eight to ten infuriated cadets. They ordered Boze to stand at attention against the wall, explaining that there was evidence of his and Jensen’s complicity in the attack on Cortez—which, Boze says, they would not reveal—and that a confession would be beaten out of them. “I’m not sure how many of them there were,” recalls Boze. “I stared straight ahead at a little blue plaque on the wall because we were struck every time we looked around or answered a question with an answer they did not like.” When Jensen’s nose and chin began to bleed, Boze was forced to wipe the blood off with his bare hand; Jensen later crumpled to the floor and rolled into the fetal position while Boze continued to maintain their innocence. “They were accusing us of trying to kill Cortez,” says Boze, “and I kept on telling them we didn’t know anything about it.” After three hours of brutal questioning, the group delivered its sentence. Across Boze’s and Jensen’s foreheads, in permanent marker, they wrote “G-U-I-L-T-Y.”

The Marine Military Academy lies on one side of the well-manicured intersection of Marine Drive and Iwo Jima Boulevard, next to the blustery airfield of the Harlingen airport; on the opposite side lies the Valley’s most potent symbol of military honor and duty, the 78-foot-high Iwo Jima War Memorial—the original plaster model, now covered in a bronze epoxy, that was used to cast the famous sculpture of six soldiers straining to plant an American flag that resides at Arlington National Cemetery. The statue’s exaggerated scale, with its dangling sixteen-foot-long M-1 rifle, dwarfs everything in its vicinity—the dusty museum next to it, filled with Purple Hearts, bayonets, and yellowed recruitment posters; the live oaks planted in remembrance of fallen Marines; and the inscription, burnished in gold, along the monument’s granite base that reads “Uncommon Valor Was a Common Virtue.”

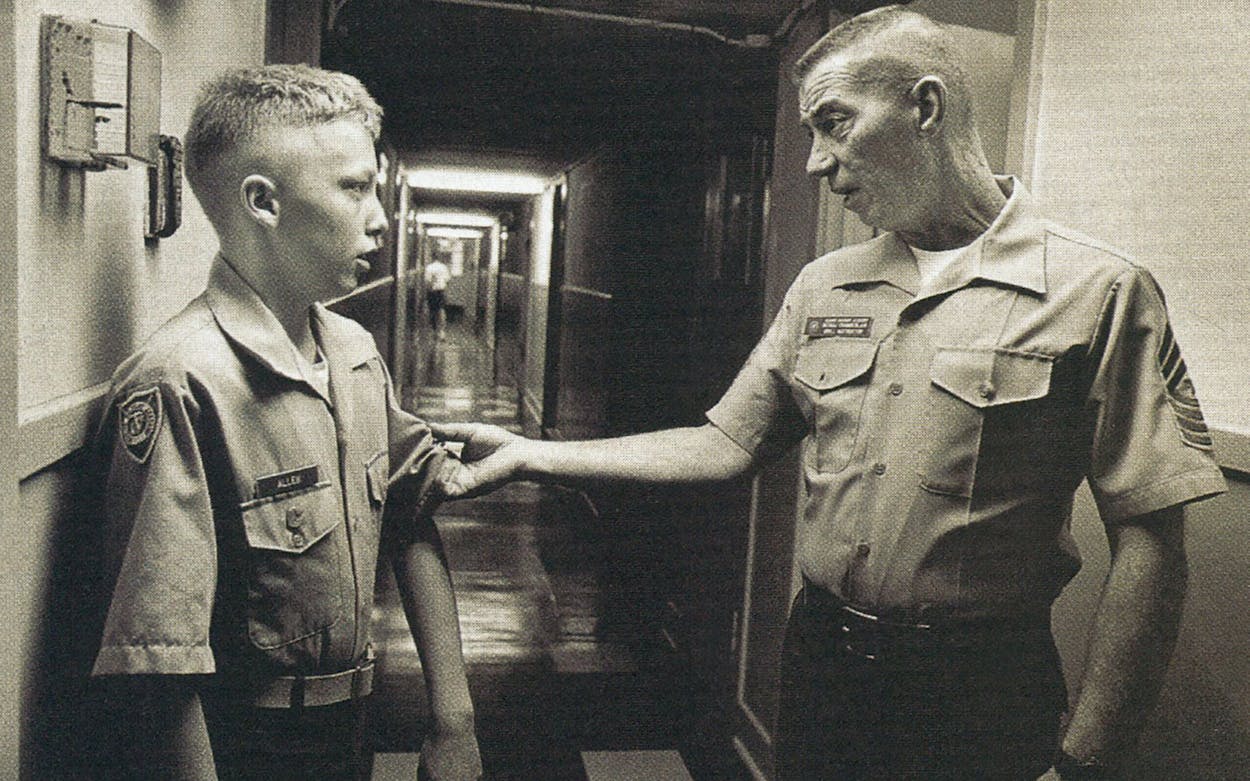

The academy is Texas’ best-known military high school and the only secondary school in the country modeled on—although not affiliated with—the United States Marine Corps, right down to its scarlet and gold colors, freshly pressed green “C” uniforms, and often-quoted Marine motto: semper fidelis, or “always faithful.” This is where wealthy Houston and Dallas families send their sons who hope to join the service someday or who, perhaps, need a little discipline. To the tune of $17,500 a year, unruly teenagers are transformed into closely cropped cadets and put through their paces by retired Marines with ramrod posture who have passed through the boot camps of San Diego and Parris Island and did tours of Korea and Vietnam. From reveille to taps, eighth through twelfth graders follow military customs to the letter, bracing for inspection and colors formation, their shoes and their brass buttons shined to a high gloss. Those who need additional discipline are often ordered to march in formation carrying rifles, scrub bathrooms with a toothbrush, or perform extra PT (physical training, or in cadet parlance, “physical torture”) in the quad, which is framed by seven barracks, each of which houses one of the academy’s rifle companies: Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, Echo, Fox, and Golf. Each company has an elaborate chain of command, and from captains down to privates, all cadets have committed to memory the hundreds of MMA rules: bed sheets are to be folded exactly fourteen inches from the top of their racks, regulation haircuts are to be trimmed once a week, ribbons are to be worn one eighth of an inch above the left breast pocket of their dress blues, and so on. At the academy, there is a rule for everything—so many rules, in fact, that they fill a 72-page manual that plebes are required to carry with them at all times.

At the academy’s helm, in a regal, red-carpeted office that overlooks the immaculate grounds, sits retired Major General Harold G. Glasgow, surrounded by mementos of 36 years of active duty in the Marine Corps. A onetime class D ball player in the Georgia-Alabama League who worked his way up from draftee to two-star general, Glasgow has the uncompromising demeanor and piercing gaze of a no-nonsense commander who takes comfort in military regimen and finds the relative chaos of civilian life difficult to grasp. He speaks passionately of honor, duty, and patriotism, of his fondness for a long-gone era of civility and responsibility, when a man could be taken at his word and when intentions were honorable. “It’s hard sometimes for our drill instructors who came through a different time, but you have to live in today’s world,” says Glasgow, who is in full military dress, his left jacket breast lined with rows of decorations for service and bravery. “I remember so vividly twenty-five years ago, all services were saying that any individual who had ever used marijuana would not be permitted to be an officer. But five years after that, there was a change.” The MMA, he explains, tries to foster the same strong work ethic and unswerving morals with which he was raised. He admits that the academy’s methods may seem dated to some—“We teach a youngster to open doors for ladies, but today he’s just as liable to get his face slapped and can’t understand why”—but he believes that the MMA’s strict discipline and honor code fill a void in today’s society, instilling time-honored ideals in otherwise impressionable teenage boys.

Even the academy’s inception during Vietnam was somewhat of an anachronism. At a time when many military schools were closing their doors, an ex-Marine and Arizona rancher named Bill Gary founded the school in 1965 so that his son could receive a proper military education. The school’s formula of austerity and military tradition proved to be popular with parents who did not agree with the permissiveness of the era, and the academy flourished in its early years. “Our whole system works on the premise that those drill instructors have the key to the liberty bus,” says Glasgow, referring to the campus bus that takes cadets into Harlingen on weekends if they have done their homework and avoided demerits. It’s a system that many here say works. Under the academy’s stern command, directionless teenagers have found purpose, many continuing on each year to Texas A&M’s ROTC program or the U.S. Naval Academy, and a handful to the Citadel or West Point. “I’ve watched the gleam that comes from a first-year cadet who’s never accomplished anything before,” says Master Sergeant Michael Krauss, who became Bravo Company’s drill instructor following the attack. “I’ve watched kids get silver wreaths [emblematic of academic achievement], who the year before could not score a .71 GPA, and watched young men who came here weighing 280 pounds weigh 185 by midterm. These are rewards for us as well, because we share in their joy.” Leslie Pritchard agrees, having witnessed one of the academy’s more remarkable success stories. “MMA has been a miracle pill,” she says, explaining that her seventeen-year-old son, Cody, had flunked out of two Dallas schools before hitting his stride at the academy. “He has a 3.8 GPA now, he was chosen Cadet of the Month—he has gained independence, confidence, self-discipline. He’s like a new kid. He’s excelling beyond my wildest expectations.” These aren’t easy victories, explains Glasgow; they are won with a firm hand.

Similarly, the general has steered the academy through new waters since he arrived in 1987, when cadets lived in run-down, poorly ventilated barracks and sometimes walked several miles in uniform into Harlingen, even in the sweltering South Texas heat. Now cadets ride the liberty bus to the mall on weekends, and the academy—whose lush lawn is dotted with sleek new buildings and the construction site for a future activity center—has a different feel, thanks to a multimillion-dollar building campaign and an enrollment that has ballooned from 336 cadets to 530. The academy’s plebe indoctrination (the grueling process of initiation into military life) has been shortened from eight weeks to three—although it’s still far from painless. “They’re pushed right down to the ground, right down to almost nothing,” says Glasgow. “Then you let them start to rise, you teach them basic ethics and values, what integrity is all about.” And plebes are no longer handed over to other cadets, or “plebe handlers,” for their initiation. Now almost all of the punitive authority that older cadets once lorded over younger cadets has been taken away—a source of never-ending frustration for upperclassmen. “Scrubbing something with a toothbrush for three hours, they don’t get the point,” says Cadet First Sergeant Frank Walker. “Physical training is more effective. You’re putting people through pain, and they understand pain.”

The academy looks more polished than ever before, but these recent changes have wrought their own particular set of problems. The school’s growing pains had gone practically unnoticed until October, when, in the wake of the attack on Cortez, the academy found itself in the spotlight. It was not the first crisis that year; in the spring, the academy had come dangerously close to losing its accreditation when it was one of two high schools out of roughly four hundred accredited high schools in Texas to be placed on probation status by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. (After hiring a guidance counselor and improving testing procedures, its status was ratcheted up to ‘warned’ this fall.) But the attack on Cortez meant that the academy had to face the scrutiny of reporters and concerned parents. In response, the institution that had deliberately sealed itself off from the civilian world for 32 years made a concerted effort to reach beyond its iron gates. “I hope that everybody has opened every door for you,” Glasgow told me after a gracious tour of the academy’s grounds this fall. “I don’t think you’ll find any secrets here.”

In an institution where symbolism deeply matters—where five-pointed stars, scarlet ribbons, and gold-plated pins dictate rank and respect—nothing could have been more emblematic at the MMA, a training ground for Marine “leathernecks,” than for a cadet’s throat to have been slashed. The attack deeply rattled parental confidence in the academy, spurring the withdrawal of 32 cadets from the school. Six days before Thanksgiving, the Dallas firm of McColl and McColloch filed a class action suit against the academy on behalf of the parents of eleven former cadets, seeking reimbursement of tuition and unspecified actual and punitive damages. The former cadets alleged that extreme acts of violence occurred in the barracks on a regular basis, calling into question the academy’s assertion that the attack on Cortez was an aberration, an act of violence unparalleled in the school’s history. “We’ve had our fair share of fisticuffs, high jinks, and wrestling around,” academy spokesman Robert Beckley told the Houston Chronicle the week after the attack, “but never a stabbing, a knifing, or a shooting or anything like that. We’re all quite stunned by it.”

Although it was true that the school had never had an attempted murder before, the former cadets’ allegations of abuse made “fisticuffs” and “high jinks” sound quaint. The former cadets in the class action suit said in interviews that the throat slashing was only the most recent and most public instance of violence to erupt between cadets and told chilling stories of cadet-on-cadet brutality, from severe beatings to sexual abuse. At a school that hardened boys into potential future soldiers, the boundaries between the necessary disciplining of teenagers and the cruelties of adolescence may have been dangerously blurred.

The class action suit was initiated by Kay Wayne, a 38-year-old Dallas single mother whose 13-year-old son returned home from the academy in the fall of 1995 with a concussion, as well as multiple bruises and contusions, that he allegedly received after being beaten by other cadets. Her son—who asked not to be identified, as did five other former cadets involved in the suit who were interviewed for this article—said that he was the victim of repeated beatings and several instances of sexual abuse, in which cadets had masturbated by rubbing against him while he was ordered to stand at attention. His tormentors, he says, went unpunished. Wayne withdrew her son from the academy after learning that he was tied up by other cadets and beaten with clothes hangers. When she began speaking to other cadets and found what she describes as a frightening pattern of abuse at the school, she decided to go forward with a lawsuit. “My son was so angry at me for putting him through that,” she says bitterly. “I wanted to be able to look him in the eye again.”

Many of the former cadets who are involved in the suit tell strikingly similar stories. Some of them were as young as twelve and thirteen years old when, they allege, older cadets beat them, holding padlocks between their knuckles and rolls of quarters inside their fists or wielding sheets that contained bars of soap and padlocks. In individual instances, they allege that older cadets grabbed them by the throat and choked them until they passed out, stabbed them with scissors, inserted mentholated balms into their rectums, smeared excrement on their faces, urinated on them, and penned explicit drawings on their bodies with markers. A few claim to have been victims of, or witnesses to, sexual assaults and rapes, which they describe in graphic detail. Their physical injuries ranged from severe bruising to concussions and ruptured eardrums; their psychic toll is unquantifiable.

If these former cadets are to be believed, how had the academy slipped so far? Numerous former employees—including board members, deans, and drill instructors, some of whom are retired Marines and all of whom requested anonymity—say the academy began to veer off track in the early nineties, when the academy’s multimillion-dollar building project created a demand for more incoming tuition money, and hence more students; the eagerness for more students, the theory goes, caused standards for admission to decline. “We never wanted to be a dumping ground,” one former board member says. “But over the years, that changed. Parents would tell the school that their children had been in a little trouble, when they had actually been in a lot of trouble. The school took kids they normally wouldn’t have taken.” The academy maintains that it does not knowingly accept anyone who has been convicted of a crime; since juvenile records are sealed, school administrators rely on what parents tell them. Two former drill instructors say that many of the cadets they supervised had been arrested before and recalled escorting cadets to see their probation officers; a third says a new student arrived on campus in handcuffs. They individually confirmed that violent confrontations happened in the barracks with regularity and named other examples, including an altercation in which a boy’s ear was bitten off, as well as an incident in which a cadet was stripped and tied to the flagpole with his mouth duct-taped shut.

“We have never condoned abuse of any cadets,” says public affairs director Robert Beckley. “Regulation 10.05 in the Right Guide [which outlines the academy’s regulations] clearly states that ‘physical abuse, ridicule, or personal degradation of one cadet by another is strictly prohibited.’ If such an incident does occur, we immediately investigate it and take appropriate action.” As for the claims leveled by former cadets, Beckley explains that “it is difficult for the Marine Military Academy to respond fully to nonspecific allegations made by anonymous plaintiffs”—referring to the fact that the suit filed by McColl and McColloch did not include details of the alleged abuse or names, dates, or places. “Until more information is forthcoming, the academy will not respond but stand ready to defend its excellent reputation of providing an environment conducive to learning and of building boys into men.”

Wayne’s suit (she has since changed lawyers) is not the first of its kind against the academy—a 1983 civil case, which was later dismissed, alleged that cadets put another cadet in a phone booth, doused it with lighter fluid, and set it on fire, and a 1995 suit that was later dropped accused several cadets of beating another with a baseball bat—but it is the largest in scale and the most serious. “I’ve had to go down to speak to MMA on at least two other occasions in the last two years, once about a hazing incident,” says Michael Thomas, a state director for the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. “In the past, the response at the school has been ‘boys will be boys,’ but that’s just not adequate anymore. There’s obviously a problem down there.” One of the most critical problems is that the school employs just one staff person, a drill instructor, to oversee each company of roughly eighty teenage boys, some of whom have been sent to the academy because of past disciplinary problems. (Marine Corps boot camps, by comparison, employ one drill instructor and at least two assistant drill instructors for each barracks, in which recruits are considerably older than the Marine Military Academy’s eighth through twelfth graders.) Former cadets say that when drill instructors retired for the evening at lights-out, the barracks became a free-for-all for abusers, and that older, more senior cadets ruled through threats and intimidation.

The school’s officials maintain that hazing is strictly against the academy’s code of conduct and insist that violators are punished accordingly. And many hazing stories, Major General Glasgow contends, are invented by first-year cadets to pull on parents’ heartstrings because they hate the rigors of military school. For this reason, parents of new students have been advised in the past not to open letters from their child for the first few weeks of school. “We had a problem for a long time with youngsters who were here because their parents wanted them here; they were doing everything in the world they could to build up a case to get themselves out,” said Glasgow in a conversation before the announcement of the class action suit. “They’d start with stories about people putting soap in socks and beating on them at night, and if that didn’t get the word across, a couple days later it would be ‘a blanket was thrown over me and somebody was hitting me from outside,’ and finally, six to eight weeks into it, if nothing worked, they’d say, ‘Mom, if you don’t come get me, I’m going to kill myself by ten o’clock tomorrow night.’ There’s such a tendency among the youth of today to yell that when they really are not serious about it at all, although a parent can’t afford to take that as an empty threat.”

But the former cadets involved in the class action suit say that they are not crying wolf—that they have left the academy far behind, but not its scars. “Remember Lord of the Flies?” asks one former cadet involved in the suit. “That’s what it was like down there. They stuck eighty kids together to fend for themselves. If you weren’t a part of the group, you were doomed.”

One student who desperately tried to fit into the group was seventeen-year-old Cadet Corporal Jeremy Jensen—a likable but “goofy” kid, in the words of his peers, who had dreams of attending Annapolis. Before starting at the academy last January, he was an average high school student from Vancouver, Washington, who had paid out of his own pocket twice a month to travel 240 miles round-trip to Young Marines meetings in Oregon, and his outstanding performance in the program had earned him a full scholarship to the academy. Jensen was excited at the prospect of getting into the Marine Military Academy and even more thrilled about leaving Vancouver and its complications behind. He had been abandoned at birth by his mother and suffered through a rocky relationship with his father, running away with a carnival when he was fifteen and later living with a Vancouver couple he called his foster parents. The academy, by comparison, seemed like a safe haven. “They say there are four ways to escape an unhappy family life: run away, get married, commit suicide, or join the military,” Jensen says. “I chose the military.”

Instead of escaping, Jensen spent two months this fall in the Cameron County jail, a depressing gray concrete building in downtown Brownsville, before being released on December 8. Jensen, along with his former roommate, Cadet Corporal Christopher Boze, had been arrested on attempted murder charges about forty hours after the attack on Cortez, on the day following their brutal interrogation at the hands of other cadets. (Boze was released the next day on bond and returned to his mother’s house in neighboring Olmito; Jensen, whose family was unable to make his $100,000 bail, remained behind bars.) The Cameron County jail is not where Jensen had planned on spending his senior year. As an ambitious junior who eagerly embraced the school’s military routine when he started there last January, he was promoted this fall and was generally well liked, although he hadn’t managed to work his way into the inner sanctum of Bravo Company’s more senior, ruling elite. But this September he received some devastating news from a Marine Corps recruiter: His asthma would prevent him from joining the Marines. His plans for the future were shattered, and he slowly lost interest in the academy, toying with the idea of withdrawing from the school after Christmas break. He stopped attending Fellowship of Christian Athletes meetings, which were popular with the corps’ high-ranking cadets, and increasingly began to pal around with his roommate.

Christopher Boze was an introverted, bookish senior with a solid academic and military record—he had had the honor of receiving two exemplary-conduct awards—who was nevertheless uniformly disliked by the corps. He was considered an oddball by many of the cadets, who described him as “weird” and “creepy” and found his skittish mannerisms unsettling. “He could tell you the name of every single part of a sailboat,” says Cadet Lieutenant Colonel Sven Jensen, referring to Boze’s fascination with marine science, “but he couldn’t hold a conversation.” Gossip about Boze’s eccentricities circulated freely in the academy’s rumor mill without regard to fact: He was a member of an esoteric Eskimo religion, went one account, and had even shot someone when he lived in Alaska; he had a cache of weapons, went another, and had once pulled a shotgun on his mother; he had threatened to throw chemicals in another cadet’s face, went a third. At a school where uniformity was the norm, Boze was a square peg. Jensen’s association with Boze caused some cadets to look scornfully upon him as well; he hadn’t just run away with the carnival, some chuckled to each other, he had been a sideshow attraction.

The two roommates say that they were just as surprised and appalled at the attack on Gabriel Cortez as anyone else in Bravo Company—that like other cadets, they didn’t learn of the assault until they were awakened and called out on line in the early morning hours of October 6. They also insist that they barely knew Cortez, a senior from Southern California who had been transferred into Bravo three weeks before he was attacked. Cortez, said one cadet, was “the kind of kid who puffs himself up by putting somebody else down.” He had an undistinguished record at the academy; after three years he was no more than a lance corporal, one rung above a private, and he had been shuffled between companies, first from Charlie to Alpha, and then from Alpha to Bravo. “He’s a wannabe tough guy,” says Master Gunnery Sergeant Jim Hager, Cortez’s drill instructor in Alpha Company, “not the martyr he’s been portrayed.”

Cortez may have earned himself a few dirty looks, but nothing worthy of an attack on his life, as far as Bravo Company cadets knew. The attack sent a chill through the barracks on that October morning, though Cortez was not in as grave a condition as had initially been feared; he was given 28 stitches before being transferred back to the school’s sick bay. “Please pray,” he wrote the next day in a letter to the corps, “for these people who have attempted to put me to rest.” Many of the cadets in Bravo feared for their lives, knowing that whoever had attacked Cortez lurked among them. “This is the straw that broke the camel’s back,” Jensen wrote that Monday in a letter he sent by overnight mail to his former Young Marines leader, asking to be withdrawn from the school. “A kid was attacked and his throat was slit. The kid was in my company and right above me. Actually one room off. Still too close for comfort. I’ve been threatened before. But I never took it seriously. Now I do.” Each hour that passed without an arrest threatened to further unhinge Bravo Company, and in the nights following the incident, panic reigned. “I don’t think anyone slept at all,” says Cadet Captain Matt Kutcher. “I had eighth graders sleeping in my room, just scared to death. It was hard, thinking that the person who did this was walking around, going to the same places you went every day.”

As Monday, the day of the attack, dragged into Tuesday without an arrest, the need to resolve the case became increasingly urgent. At least one cadet is said to have reported seeing Boze and Jensen running back to their room immediately after the attack on Cortez. Eyewitness accounts may be questionable, since all the cadets have identical haircuts and clothes and because the barracks were dark at the time of the sightings. Whether this was the reason that some cadets concluded that Jensen and Boze were the attackers is unknown; the academy would not allow them to answer questions about motive or guilt. On Tuesday night, Harlingen police officers arrested the roommates on attempted murder charges. Jensen and Boze were handcuffed and driven out of the academy’s iron gates in separate squad cars.

But at press time, the case was no closer to being solved than it was in October. One day before Jensen’s December evidentiary hearing, prosecutors dropped charges against him, pending further investigation; Boze, who was already free on bond, remains charged. It is conceivable that either or both boys could be indicted when the grand jury meets. The Harlingen Police Department and the Cameron County District Attorney’s Office have remained tight-lipped about the investigation and will not reveal whether there is physical evidence that points to the two cadets, who steadfastly maintain their innocence, or a plausible motive. Cortez and Jensen had had at least one scuffle this fall, when Jensen sat on Cortez’s desk—“Gabriel doesn’t like it when people touch his things,” his mother explains—and cadets speculate that Boze, who was sensitive to slights, may have been a target for Cortez’s taunts. Was that enough reason to make the roommates want to teach him the ultimate lesson? Or, in a company pushed close to the point of hysteria, were Jensen and Boze the most logical fall guys for a crime that desperately needed to be pinned on someone, quickly?

By all external appearances, the academy was back in full swing a month later at the Marine Corps Birthday Ball, a formal dance in which the spit-and-polish cadets wore their dress blues and nervously pinned corsages on their dates, who had flown in from Dallas, Houston, and elsewhere around the country. Jensen and Boze were already far removed from the school, awaiting indictment; the cadets who had interrogated them had been stripped of rank; Bravo’s drill instructor had been relieved of duty; and the purple scar along Cortez’s neck was beginning to heal. Most importantly, the Leathernecks, the academy’s football team, had beaten their rival team, the Harlingen High Cardinals—a particularly sweet victory for the cadets, who had grown tired of students at rival schools dragging their fingers across their necks at football games.

But beneath the academy’s veneer of tranquillity, not everyone’s mind has been set at ease. Cortez sleeps in a room specially outfitted with locks in Gulf Company, where he was transferred the week after the arrests because he didn’t feel secure in Bravo. “He told me that he wakes up at night,” says his mother, “and thinks—imagines—that someone is trying to open his door.” Meanwhile, the academy, which would like to put the terrible night of October 6 behind it, instead will be forced to answer difficult questions in the upcoming months, not only in regard to the attack on Cortez, but also about the allegations leveled in the Dallas class action suit. In addition, two criminal trials of cadets have been set for 1998. In one case a seventeen-year-old cadet will stand trial for allegedly beating a fourteen-year-old cadet (his injuries included a concussion, bruises, and a swollen face); in another trial two cadets—who allegedly assaulted another cadet to prevent him from testifying against them in court about a separate charge of unauthorized use of a vehicle—will be facing charges of retaliation. As these cases slowly unfold in courtrooms this year, an academy that remains stubbornly committed to the virtues of the past will be forced to confront the tragedies of the present. For the attack on Cortez was also an assault on the corps as a whole—an indictment against a code of conduct that has proved enormously successful for military men but is potentially troublesome for boys. In the light of accusations by former cadets that they learned to “give as good as they got,” it is arguable that the academy’s students are too young, and in some cases too troubled, to appreciate and embrace Marine Corps values without perverting them.

In the wake of the attack on Cortez, uncertainties linger as to whether the academy can teach discipline without cruelty. “If I had to make an assessment at this time,” Glasgow said of the throat slashing a few weeks after the attack, “I would tell you that two youngsters decided for one reason or another that they were going to administer what they would call ‘rites of passage’ to a youngster who was new to the barracks. Is that acceptable? Not under any circumstances—that is not something we would tolerate. We are taking extra precautions to preclude this or any other hazing from occurring. We are establishing TV monitors in each of our barracks; our drill instructors will make two additional tours of the barracks each night; and we’re putting in two more staff duty noncommissioned officers, who will make two tours each night,” he said sternly from the recesses of his office, his words seeming to echo, like the past glories of the academy. “We will keep the lights on.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Military