The late afternoon of March 25, 2012, a voice crackled over the police scanners that perch on the coffee tables or hang on the belts of many residents in San Saba: an ambulance was headed out to Harkey Pecan Farms. Scanner chatter is a rich source of gossip in this tiny Central Texas city of 3,099, and ears perked up that Sunday as paramedics and law enforcement officers rushed four miles west of town to Harkeyville, where a 1927 red-brick house sat among three hundred acres of pecan orchards. The Harkeys had long been one of San Saba’s most prominent families, and their property sat next door to a stretch of pastureland owned by another notable native son, the actor Tommy Lee Jones.

Sheriff Allen Brown was already out on patrol when the 911 call came in. He sped down U.S. 190 in his white truck, passing neatly tended rows of pecan trees and the cattle auction barn, then crossed the San Saba River and rumbled down the caliche road to the two-story house. He knew the house well; since the early sixties, generations of San Sabans had attended the church suppers and cookouts hosted there by Bonnie Harkey, the family’s matriarch. Bonnie, her white puff of hair always freshly coiffed, was a fixture of San Saba’s social scene, known for never missing a Sunday school class or a meeting of the garden club. Her pecan-based desserts were legendary, often earning her first place at the county’s pecan food show and a front-page mention in the San Saba News & Star. But she was now 85 and increasingly frail; it was common knowledge that she was suffering from dementia and required the attention of a caretaker. Six months earlier, she had been diagnosed with an aortic aneurysm, and it was only a matter of time, everyone knew, before it claimed her.

But when Brown arrived at the house, he found a puzzling scene. Bonnie’s caretaker, a fifty-year-old redhead named Karen Johnson, was sprawled facedown just inside the front door, atop the floral doormat. Her reading glasses were resting on the floor beside her head, and she was cool to the touch. The paramedics who arrived five minutes later quickly determined she was dead. What had happened to Karen? And where was Bonnie? Karen’s eleven-year-old son, who had found her and called 911, stood on the front porch clutching a cordless phone. He had been playing video games in another room, he said through tears, and hadn’t heard any commotion. There was no sign of a struggle, except for a broken fingernail on Karen’s right hand. Brown wondered if Karen had died of natural causes and if Bonnie, confused upon discovering her body, had simply wandered off.

There was plenty of space for her to do so: the orchard closest to the house stretched almost to the river. A search team, which included volunteers on ATVs, local firefighters, sheriff’s deputies, and a bloodhound named J.J. from the nearby state prison, soon fanned out across the property. A DPS helicopter dispatched from Waco made slow circles overhead, scanning the ground with heat-imaging cameras. Searchers tramped past a barn, an old metal shack, through the high grass of the riverbank, and along Tommy Lee Jones’s fence line, where horses grazed sedately on the other side. The fear was that Bonnie had tripped in the orchard or somehow fallen into the river. But both those possibilities were excluded when the bloodhound, using a scent swab from her pillow, followed her trail down the driveway almost to the road, indicating she’d likely left in a vehicle. Where was Bonnie?

That question would be answered 27 hours later and 178 miles away in Leon County, when several Texas Rangers, sheriff’s deputies, and cadaver dogs found Bonnie’s body in a creek bed near an RV campground in Normangee. She was curled into the fetal position and buried under a thick layer of leaves, mud caked into her white curls. An autopsy would reveal that she had been hit over the head and drowned in the shallow water.

It was the kind of horrific end no one could have imagined for the demure Harkey matriarch. But as an ensuing investigation would soon reveal, her death represented the final, sordid unraveling of one of the oldest lineages in Central Texas—the story of a family tree rotted through by the destructive forces of obsession, greed, and hate.

Wild pecan trees, Carya illinoinensis, have flourished throughout the South for millennia, and thousands grow along the rivers of Central Texas; when the explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca was held captive by Indians on the Guadalupe in 1532, he christened it “the river of nuts.” But human cultivation of pecans in Texas began in San Saba in 1874, with the arrival of Edmund E. Risien. An English cabinetmaker who was captivated by the wrinkly nuts, Risien offered a $5 prize to whoever brought him the finest specimens. He traced the winning nuts to a tree he dubbed the Mother Pecan, then began growing his own through novel pollination and grafting techniques, earning himself the nickname “the Johnny Appleseed of pecans.” His efforts made the trees commercially viable, and Risien became the nuts’ biggest booster, mailing samples to Queen Victoria and Alfred Lord Tennyson. Today pecans are central to the economy of San Saba, which produces up to five million pounds a year and claims to be the Pecan Capital of the World (a title contested by Albany, Georgia, and Chandler, Oklahoma).

The Harkeys were one of the first families to settle the area, before pecans were an industry. According to one newspaper account, Riley and Israel Harkey, two brothers from Arkansas, drove the first wagon train into the county while serving as Indian scouts for the Republic of Texas; they became so enamored of the loamy soil in the San Saba River Valley that they returned in 1855 with their parents and six other siblings. The Harkey brothers founded Harkeyville, which in its heyday would boast a general store, a cotton gin, a blacksmith shop, a baseball diamond, a millinery, and a racetrack. Before the Great Depression shuttered most of the town, the racehorses and mules bred by Riley were known to attract crowds of spectators from all over Texas.

It was Riley, a man with a long, bushy goatee and square head, who purchased the initial 113.9-acre tract for a farm in Harkeyville in 1885, and it was on this farm that his grandson and eventual heir, Olga Bryan Harkey, was born, in 1898. Native pecan trees already dotted the property, including one that the San Saba News would later proclaim to be among the “most beautiful and symmetric pecan trees in the county,” but O.B., as he was known, planted the family’s first orchard in 1926, installing a grove of 1,200 trees and naming it the Home Place Orchard. He considered the pecans a hobby, however; his primary interest was turkeys, which he bred by the thousands and shipped as far away as North Dakota and New Hampshire. (“They have been breeding for perfection and believe now they have a strain that gives Turkeydom about everything that is to be desired in a turkey,” the News gushed in 1932.) Still, in 1957, O.B. and his only child, 32-year-old Riley, together with Riley’s two sons—ten-year-old John and five-year-old Bruce—planted another 1,500 trees, in a grove that came to be known as the Harkeyville Orchard. As the farm’s two orchards matured, they began to yield a handsome profit.

What had been his father’s hobby became Riley’s livelihood. Though pecan trees can grow with little to no help, they are famously temperamental when it comes to producing high-quality nuts, and Riley made himself an expert—learning how to graft buds onto a seedling, trim back branches, and fertilize with zinc. He became the head of the San Saba County Pecan Growers Association, and around town, farmers sought him out for advice. Wearing his thin, light-blue coveralls, Riley dispensed tips on everything from soil drainage and fertilization techniques to how many grazing sheep to allow in the groves and how to stave off “pecan scab,” a type of fungus that looks like a horticultural syphilis. No detail in his orchards escaped him. “Riley had his own way of doing things,” recalled Winston Millican, a great-great-grandson of Edmund Risien’s who maintains his own pecan orchards in San Saba. “They still handpicked all their pecans way up into the eighties and nineties. Nobody else did that after the seventies.”

Perhaps it was Riley’s work ethic and stature that first caught the attention of Bonnie Sawyer Compton. When she and Riley were introduced, in early 1963, the tall, 36-year-old brunette was working as a telephone operator in Waco, a divorcée trying to make ends meet. Her ex-husband, a traveling salesman, had left her for another woman, and Bonnie had moved from Ocee to the city with their daughter, fourteen-year-old Connie. Bonnie, who grew up in a farming family during the Depression—her father planted cotton, corn, and wheat—had always longed for a grander life. “It bothered Bonnie that we didn’t have any money growing up,” recalled her sister, Wilma Cook. “She never said anything about it, but I could tell by the way she acted.”

If Riley represented security, Bonnie, for her part, embodied the kind of feminine presence that was missing from the Harkey household. Riley’s wife, Joan, had recently walked out on him and their two boys after a troubled marriage, packing up her Ford station wagon and hightailing it to the desert of Nevada. Bonnie, with her hazel eyes and red-tinted hair, as well as her knowledge of motherhood, was instantly attractive to Riley. After a brief courtship, the two were married at Waco’s Highland Baptist Church that April, one month after his divorce was finalized. Bonnie quit her job at the telephone company, and she and Connie moved into the Harkey house.

No longer a single mother, Bonnie found herself joining clubs, making friends, and sliding into the comfortable life she had always wanted. “If there was a club in town, she belonged to it,” said Betty Ann Johnson, a San Saba resident and Bonnie’s friend of forty years. Bonnie, a staunch Baptist, persuaded Riley, a lifelong member of the Church of Christ, to attend San Saba’s First Baptist Church with her, where Betty Ann and her husband, Craigan, also attended. The Johnsons and the Harkeys became great friends, going out to dinner and traveling to gospel concerts in Marble Falls and Burnet. Bonnie entertained often, volunteering her home for garden club and church functions, serving up sandwiches, cakes, and other dainty refreshments on fine china.

A devout reader of Better Homes and Gardens—she stored all her back issues neatly in the laundry room—Bonnie also put her stamp on the house, turning a closet into a bathroom, adding on an extra bedroom, and building a sunporch that could comfortably seat up to 27 people. Eventually the home would reach 4,872 square feet, many of its corners filled with family mementos: award ribbons and plaques for Riley’s pecans and Bonnie’s pies; framed photos from the couple’s trips to the Bahamas and San Antonio; Bonnie’s collection of Desert Rose dishes; her still-life paintings of roses and yuccas; the Harkey family Bible, set on a lace doily in the sitting room, Bonnie’s looped cursive marking big life events inside.

Riley, meanwhile, focused on the family’s holdings outdoors, tending as always to his pecan trees. “The care of the orchard was very important to him,” remembered Millican’s wife, Kristen, who grew up across from one of Riley’s groves. “The way it looked, making sure it was well manicured.” Yet while their life appeared to be in perfect order, Bonnie and Riley’s marriage was not always a happy one. “He often criticized her. When she’d tell a story, he’d interrupt and say, ‘No, that’s not the way it goes,’ ” recalled Bonnie’s sister. “They didn’t care if they were in public or not. Riley would tell her something wasn’t right, and she would say it was, and they’d get in a big fuss over it.”

One major source of tension was their blended family. The three kids did not take well to one another, and John and Bruce treated their stepmother unkindly from the outset. “They would laugh at her and criticize her food,” her sister continued. “They’d take a mouthful of food and spit it out, or they’d talk about her, giggle all the time, act rude. They had not been trained to be nice boys.” Though Bonnie tried to impose some structure, taping a list of rules to Bruce’s bedroom wall at one point, Riley rarely stepped in to discipline them.

The boys’ misbehavior got to be so unpalatable to Bonnie’s relatives that they stopped coming out to San Saba for holiday dinners. “I think part of their attitude goes back to being a Harkey,” said Teresa Cook, Bonnie’s niece. “They thought the whole county should still revolve around them. Riley trained his sons—he told them that as Harkeys they were special.”

As a kid who grew up playing in the Harkey orchards and often walked the rows with his grandfather O.B., Bruce was familiar with the dangers that could threaten a prized pecan tree. There was drought and sudden freeze and poor soil drainage. There was bunch disease and stem end blight and fungal twig dieback. There were weevils and caterpillars and webworms. And then there was cotton root rot, the most pernicious of diseases, which could kill a tree from the inside. Invisible to a farmer, the devastating fungus would stealthily invade through the roots, withering the leaves in an instant and killing the tree seemingly overnight.

But on their walks, O.B. mostly concerned himself with fire ants, which can hamper the grafting process and damage expensive irrigation equipment. “I can’t tell you how many hundreds of miles my grandfather and I walked in that Harkeyville Orchard,” said Bruce recently. “His left arm was taken off above the elbow in an accident in the late fifties, but he’d tuck a grub hoe under his stub and put a mayonnaise pint jar in his hip pocket filled with ant poison. He would go along and dig up an ant bed, and he would sprinkle them, and we would go to the next tree,” Bruce recalled.

Bruce looked forward to the day when he’d take care of the orchards himself. He expected that his father would hand over the day-to-day operations of the farm in the same way O.B. had ceded oversight to Riley in his thirties, moving out of the red-brick house and into town. Of his two grandsons, in fact, O.B. could tell that Bruce—whose given name was Bruce Wayne, after the superhero—had the keenest interest in farming.

Bonnie’s arrival, however, when Bruce was eleven, made the future uncertain. He sensed her reluctance to embrace him and John, feeling her disdain as soon as the wedding was over. In one anecdote he liked to tell, she made her feelings clear one afternoon when the family was in her new desert rose Thunderbird. “I was in the backseat, and I leaned forward and said, ‘So, do we call you Mom now or what?’ ” he said. “I still have the scar where my brother kicked me. But all she did was laugh. She never responded.” According to Bruce, Bonnie issued an ultimatum shortly thereafter. “You get rid of that kid or I’m going back to Waco,” he claims she told Riley.

Whether Bonnie was the instigator or not, it is true that those years were unstable for Bruce. John packed up in the fall of 1965 to attend Texas Tech University, in Lubbock; Connie enrolled there two years later after being named San Saba’s homecoming queen. Bruce, meanwhile, was shuttled back and forth a few times to live with his mother in Nevada (one move, when he was fourteen, was announced in the News & Star with the headline “Bruce Goes West”). When he returned to San Saba for high school, Bruce moved in with his grandparents in town rather than live with Riley and Bonnie. Handsome, with sandy-brown hair, Bruce busied himself with a slate of extracurricular activities—Spanish club, student council, Future Farmers of America—and soon figured out how to charm girls with his mischievous smile.

One of those girls was Judi Bishop, one year older and from Goldthwaite, a town 22 miles north. Teenage flirtation gave way to sobering reality with an unexpected pregnancy, however, and the two were married in August 1969, on a Friday evening at the start of Bruce’s senior year. The newlyweds moved into an apartment in town; Bruce went to class and worked at a Texaco station. On April 1, 1970, a month before her due date, Judi gave birth to the next Harkey: a seven-pound, two-ounce boy named Eric.

The baby seemed healthy, but shortly after his delivery the couple learned that his epiglottis was not fully formed, which meant that after feedings Eric had to be held or laid on his stomach so that he wouldn’t choke on spit-up. At Bonnie’s invitation, the young family stayed out on the farm for several days as they got the hang of new parenthood. But then things went suddenly and terribly awry: on April 15, as Bruce sat in English class, the baby stopped breathing. Bonnie, who had been watching Eric, rushed him to the hospital, but by the time she got there, the baby was dead. (The official cause of death was aspiration asphyxiation.) The fourteen-day-old infant was buried in the city cemetery the next day; two of Bruce’s wedding ushers were among the pallbearers, and Riley helped Bruce pick out the gray granite headstone.

Bruce and Judi were devastated. Bonnie, too, was grief-stricken. That summer the couple left San Saba and moved to Lubbock, where, like his siblings, Bruce enrolled at Texas Tech. But the marriage couldn’t weather their sorrow, and by January they had divorced. For Bruce, the following decades would turn into a blur of shifting relationships and jobs. He rekindled a romance with a high school girlfriend, Jennifer Karnes, whom he persuaded to move to Lubbock and marry him, but she grew unbearably homesick and their union lasted only three months. He dropped out of college and moved west, driving trucks in California and holding odd jobs before finding work in Nevada as an officer in the Reno Police Department in 1978. He got married and divorced two more times—a daughter was born in 1982—and then returned to Texas, where in 1987 he snagged a plum position in the Texas attorney general’s office investigating Medicaid fraud and nursing home abuse.

Back in San Saba, meanwhile, Bonnie and Riley had become grandparents again. Connie, who had married after college and moved to Fort Worth, adopted an eight-month-old in 1984, a baby that she and her husband named Carl Pressley. Bonnie doted on the strawberry-blond little boy, proudly displaying his photos on her mantel. (In one, Carl, around eight years old, sits next to Santa in a red cap, while Bonnie sits on Santa’s lap in a Christmas sweater.) Riley, for his part, began turning his thoughts to the future, and in 1991 he purchased a third pecan grove, a 94-acre plot of young trees called the Prichard Orchard. He willed it to Connie, while the other two groves were to go to John and Bruce, so that all three kids would have their own orchards someday. (John by this time had settled outside Fort Worth and had three children of his own.) In the meantime, if Riley died first, Bonnie would maintain a life estate over all the property.

Proud of his planning, Riley trumpeted what he had done around town. Clydene Oliver, the proprietor of Oliver Pecan Company, remembers when Riley, who often sold nuts to her family in bulk, dropped by her storefront on West Wallace Street. “He sat right on that chair by the door and talked about it one day for a long time, about how he had it all fixed and there wouldn’t be any problems,” Oliver told me recently. “He thought everything would be fine and dandy because the two boys knew what they were getting and Connie would get a pecan orchard too.”

For Bruce, however, the farm remained a source of tension. Over the years, he had started to wonder whether Eric might have lived if Bonnie hadn’t been the one watching him. This idea consumed him. And although he was still drifting—by 1994, when he switched jobs to become a nursing home administrator, he was on wife number seven—he nevertheless held out hope that his father would hand over the farm’s operations. In 1996, shortly after his forty-fourth birthday, Bruce married his eighth wife, a twenty-year-old named Kami Jones, and the couple drove out frequently to visit Bonnie and Riley. But his father resisted any overtures, preferring to run the farm himself, with Bonnie at his side. Bruce seethed. “He would say stuff like, ‘Well, they just need to die so that I can have the farm,’ ” recalled Kami.

Riley did die, in July 1997, after succumbing to advanced bone cancer—the result, a few townspeople speculated, of exposure to the chemicals he sprayed on his pecan trees. But to Bruce’s dismay, Bonnie effortlessly took on the role of family matriarch. In a good year, the three orchards brought in more than $100,000, so Bonnie remained comfortably in the house, paying longtime foreman Gaspar Carachero to maintain the farm. That December, she won second place for her pie and cookie entries in the San Saba County Pecan Food Show; the next year she was on the front page of the News & Star holding a plaque for her champion pecans. It was almost more than Bruce could bear. “As he saw it, Bonnie was staying on his birthright,” said Kami.

Whether the cause was resentment or desperation, Bruce’s life began to unspool soon afterward. He grew controlling in his marriage, abusing Kami verbally and then, after she gave birth to their daughter in 1998, physically. He would choke her, pull her hair, and eventually even hold a gun to her head, threatening to kill her for a perceived slight such as not having dinner on the table by six o’clock. Finally, when their daughter was four, Kami worked up the courage to walk out.

Bruce, upset about being left again, told a co-worker at the nursing home that he was contemplating Kami’s murder. He gave the co-worker three guns—two old Chinese military rifles and one semiautomatic .22—asking him to obliterate the serial numbers; he also talked about rubbing poison on Kami’s steering wheel. The co-worker and Bruce’s boss became so alarmed that they alerted the authorities, and a Texas Ranger and an ATF special agent began to record Bruce’s conversations. They set up a sting operation, in which an informant provided Bruce with an illegal silencer and federal agents then arrested him, charging him with possession of a firearm in connection with a crime of violence. Bruce pleaded guilty to a lesser charge, and at his sentencing, his lawyer tried to argue that he had simply been all talk. The judge disagreed, sending Bruce to federal prison for five years.

He was released in December 2007, and after a brief stint in an Austin halfway house, Bruce returned to San Saba for good. He needed an address to satisfy probation requirements, so he sent letter after letter to Bonnie, begging her to let him live on the Harkey farm. After talking the matter over with her pastor, Bonnie finally agreed. Bruce moved into an upstairs bedroom, where he was joined by his ex-wife Jennifer Karnes, with whom he’d renewed a relationship after divorcing Kami. They brought their own refrigerator, microwave, and coffeemaker and remarried the next fall. “Bruce and I just kind of confined ourselves upstairs and made it into a little apartment,” recalled Jennifer.

But Bruce, now a convicted felon, had trouble finding work. He did odd jobs, helped out around the farm, and went into town to buy groceries for Bonnie, who had started to grow feeble. “The orchards were in such horrible condition, because Bonnie and Connie didn’t know how to run a farm or what to do with pecan trees,” Jennifer told me. As a favor to their friends’ son, Betty Ann and Craigan Johnson hired him to clean out their barn, but the work was short-term. One afternoon, he showed up at Oliver Pecan Company an hour before closing time to ask for a job. “He just had a meltdown. He stayed for about two hours and cried,” recalled Shawn Oliver, Clydene’s son. “He told me, ‘I’m the brokest millionaire in San Saba County,’ because he had the property he couldn’t touch.”

Bruce’s financial problems were real: he had filed for bankruptcy in 1998 to discharge $176,256 worth of debts, and he owed more than $100,000 in back child support to Kami. But his narcissism did little to endear him to the residents of San Saba. “If you asked him what time it was, he’d tell you how to build a watch,” said Steve Boyd, a former Texas Ranger who succeeded Allen Brown as sheriff in 2013. Bruce claimed he’d been framed in the federal case, but many around town distrusted him, suspecting something was amiss in the Harkey family. “There are no secrets around here, and if there is a secret, someone will make up a story to fill in the gaps,” explained Boyd. “The Harkeys had that reputation—that there was always some trouble brewing after Riley died. I guess with any big estate worth any value, if you’ve got a bunch of people involved, there’s going to be fuss.”

Bruce began to spend more time with his nephew Carl, who was now 24. As a boy, Carl had suffered from ADHD and often butted heads with his mother; as a young man, he’d developed a love for motorcycles and meth, which had worn his bottom teeth down to little yellow stubs. He had lived with Bonnie for a few years as a teenager, and his grandmother spoiled him, indulging every whim: when he ruined his truck, she bought him a new one; when he said he wanted to raise Boer goats, she bought him a flock of redheaded kids; when he brought home a stray dog, she let him keep it. Carl had dropped out of high school after eleventh grade and gone to work in the oil fields around Midland; following his return, he’d married a local woman named Melissa Pafford, in 2003, when he was 19. Though the couple had a daughter and a son, they ended up separating, and Carl started dating Lillian King, with whom he had another daughter, in 2008.

While Bruce had never harbored warm feelings for Carl, the younger man sought desperately to impress his uncle. Like Bruce, Carl had a rap sheet, which included charges for trespassing and domestic violence—in 2005 he’d allegedly tried to run over his stepfather with a tractor—and he also had an eye for pecans: after realizing that a truckful of nuts could net him several thousand dollars, he’d begun filching them from Bonnie’s barn. “Carl would show up with a pickup full of pecans, and we bought them. We didn’t know he had stolen them,” said Shawn Oliver.

Carl also had a temper, one so volatile that First Baptist Church barred him from the premises after he showed up at Bible study one Wednesday to demand money from Bonnie. “If he was coming to worship and study, that was fine, but we didn’t want that anger,” explained Pastor Sam Crosby. Another time, when Bonnie refused to buy him a set of new tires, Carl blocked her car with his truck and refused to let her leave. Despite these outbursts, she continued to write checks for him. “The more we tried to convince her to get away from him, the more she would say it was not the Christian thing to do. But he was bleeding her dry,” said her niece Teresa Cook.

It didn’t help that Bonnie was showing signs of dementia. She got confused at church, showing up at the wrong Sunday school class one week. She also wrote large checks to foreign telephone scammers. After Connie had her mother’s driver’s license revoked, in 2009, Bonnie’s condition only worsened. Though Connie became her temporary guardian, more instability ensued. John joined with Bruce in court to try to remove Connie as guardian; they failed, but then Connie died suddenly, in March 2011 at age 62, after a bout with pneumonia. A local lawyer by the name of Dick Miller stepped in on Bonnie’s behalf, asking his law partner, Darrel Spinks, to get involved. Soon a court had appointed Spinks as the permanent guardian of Bonnie’s estate and her longtime friend Betty Ann as the guardian of her person.

Despite the chaos, Bonnie remained lucid about some things. In a heartbreaking letter to the Texas Department of Public Safety to contest the revocation of her license, she wrote, in shaky cursive: “I really don’t know what caused someone to report that I am incapable of operating an automobile. I try to be careful when driving. I do not take any medicine that would cause unsafe driving. I do drive slowly more times than I should because I would not want to hurt anyone. I do have family who want the property I live on and I have heard many times they want to get rid of me.”

Betty Ann stopped by the house twice a day and hired caregivers who could be with her around the clock. In September 2011, Bonnie was diagnosed with an abdominal aortic aneurysm, which the doctor explained could take her life at any moment. But he didn’t think she would survive the surgery to fix it, and Bonnie insisted on spending whatever days she had left in the house. “Every time I went, she said, ‘Please do not let them take my home away from me, Betty Ann,’ ” recalled her friend. “ ‘I want to stay here as long as I can.’ ”

Bruce and John, however, with their inheritance in sight, had already begun some wrangling over the property. In May the brothers had persuaded Carl to sell them his future rights to the Prichard Orchard for a measly $75,000, even though the property was valued at more than $500,000. (Since Bruce was broke, Carl didn’t see any of that money until August, when Spinks approved the sale of a large wheat field to a neighbor for $95,000; Carl accepted a check from Bruce for $7,500.) With rights to the Prichard Orchard secured, the Harkey brothers now set their sights on a potential buyer: their reclusive yet high-profile neighbor Tommy Lee Jones.

The famously craggy-faced movie star had been buying up property near his hometown since 1981, slowly amassing a 5,050-acre ranch in the eastern part of San Saba County. Then, in 2007, he’d looked west, buying the 209-acre strip of farmland adjacent to Harkey Pecan Farms, where he grew wheat and grazed his horses. Now word around town was that he’d begun to eye the Prichard Orchard. (Many think Jones was less interested in pecans than in the excellent water rights that come with the property.) John and Bruce reached out, and after some negotiation through an intermediary, Jones put down a $541,822.50 offer on the orchard. A contract was immediately drawn up.

Except there was one wrinkle. It didn’t matter that Carl had signed away his rights—Bonnie still had a life estate in the property. Spinks, after looking over the deal, found that the terms were not beneficial to Bonnie and refused to sign off on it. Bruce was infuriated. He was already resentful of decisions Spinks had been making—this was the last straw. “Bruce called me in the mornings, in the evenings, on the weekends. He was just incessant. The relationship devolved rather quickly,” recalled Spinks. One thing they’d disagreed on was the day-to-day operations of the farm; Bruce wanted Spinks to pay him a salary to manage the orchards, but Spinks leased the property to Winston Millican. (“Farming is gambling, and I didn’t think that was the most prudent thing to do with an eighty-four-year-old’s money, when she might need it for hospital care,” Spinks said. “I needed to shift the risk to the lessee.”)

With no money from Tommy Lee Jones and no authority to care for the orchards, Bruce was left to pine for his stake in Harkey Pecan Farms from a distance. By this time he and Jennifer had moved to his grandfather’s house in town, and to anyone who would listen, he complained loudly about Millican’s work, finding fault with everything from the way he trimmed branches to how he irrigated. On days when Millican was in the groves, Bruce would park his silver F-150 in a neighboring field and scrutinize from afar. Watching through a pair of binoculars, he’d stare, for hours at a time, at the orchards that weren’t his.

March 25 is known as Pecan Day, marking the date in 1775 when George Washington planted 25 pecan trees at his home in Mount Vernon. In San Saba 237 years later, March 25 dawned as an unremarkable Sunday. Bonnie Harkey woke up and ate breakfast, and then Karen, her caretaker—who’d brought along her young son for the day—drove her to church in Bonnie’s gold Chevy Malibu. After Sunday school, the two women attended the ten-thirty service, sitting as usual in the sixth row and listening to Pastor Crosby’s sermon from Acts, about the stoning of Stephen. Afterward, they returned home, where Bonnie changed out of her Sunday best and into a teal tracksuit. Karen’s son retreated to a spare bedroom to play, and Bonnie settled into her maroon recliner in front of the television with her beloved cat, Miss Kitty. A copy of the Baptist magazine On Mission sat on the table beside her.

But then what happened? After reconstructing Bonnie’s movements that morning, the search team was stumped. As volunteers combed the property, chief deputy Bill Price returned to the sheriff’s office to work the phones. Just after eight-thirty in the evening, a call came in. Lillian King’s mother, who knew that her daughter and Carl had been out at the Harkey house that afternoon, had asked a friend to contact the sheriff when she learned that Karen was dead. “I know things are crazy right now, but I might have some information about where Bonnie Harkey is,” the friend told the dispatcher. “I’m ninety-nine percent sure that Carl Pressley’s involved.”

Deputies spent the next few hours trying to track down Carl and Lillian, requesting a DPS Silver Alert for Bonnie and a statewide search for Carl’s Mustang. Finally, at two in the morning, after repeatedly calling Carl’s cellphone, Sheriff Brown reached Carl himself. He and Lillian were out in Normangee, four hours east of San Saba, staying at a campground. The two needed to get back immediately, the sheriff told him: Karen was dead and Bonnie was missing. “Carl started crying at this point,” Lillian later recalled. “But they weren’t real tears.”

Just before daybreak, Carl and Lillian arrived at the San Saba County jail, a compact limestone building that is the oldest continuously operating jail in the U.S. They were separated immediately for questioning, and it wasn’t long before Carl admitted that they had taken Bonnie for a drive in his car. But he said they’d gone to the San Saba River—a lie that caused Lillian to break down and spill the real details as soon as Price tried to cross-check the story. (“It was eating me alive, I just couldn’t do it anymore,” she said.) After that, Price and Sergeant John Wilkerson moved Carl to the sally port of the jail, where they could use a patrol car’s dash cam to record the interrogation. (“We don’t have the budget of big cities, so we had to use the same thing we use to record traffic stops to record a capital homicide confession,” explained Wilkerson.) Two hours later, a blubbering Carl finally admitted he’d killed Bonnie and left her body in a creek near the RV.

“She ain’t going to forgive me,” Carl told Wilkerson through tears. The sergeant did his best to reassure him: “Your grandmother’s forgiven you for everything else.”

But Carl was inconsolable, the day’s events washing over him with sudden, horrifying clarity. Lillian had dropped him off at the house while Bonnie was at church; he’d climbed in through a window and hidden downstairs, smoking meth while he awaited her return. When Bonnie and Karen got home, he texted Lillian, who was to come back and ring the doorbell, serving as a distraction while he tiptoed into Bonnie’s bedroom. He’d planned to smother Bonnie with a pillow at naptime and then sneak out, but when Karen spotted him as she answered the door, he panicked, tackling her in a bear hug and throwing her to the floor, where he suffocated her beneath his body weight. Lillian, meanwhile, kept Bonnie occupied in the wood-paneled living room, their conversation and the TV muffling the sounds of Karen’s struggle.

Carl then went to find Bonnie and asked if they could pray together in her bedroom. She agreed, and after sitting together at the foot of the bed, Carl lunged toward her with a pillow. He stopped short of smothering her when he thought he heard the doorbell; when Bonnie called out to Lillian that Carl was trying to kill her, he convinced his disoriented grandmother otherwise, saying they should all go for a drive. The three got into Carl’s car—he insisted that Lillian drive because his license had been revoked—and headed to the campground in Normangee, where a friend from his motorcycle club had loaned him an RV. By the time they arrived, it was evening, and Carl told Bonnie that he wanted to show her “a real nice fishing hole.”

They walked to a nearby ravine and down the embankment to a small stream. There, he hit her over the head with a dead tree branch and pushed her face into the ankle-deep water until she stopped struggling. He covered her lifeless body with fistfuls of leaves and mud.

During the interrogation, Price asked Carl a question. “Who else is involved in this?”

“Lilly,” Carl said quickly.

“Who else?”

Carl paused for a moment and looked down. “Bruce said he wanted me to get rid of her and take her—he’ll put money in my bank account.”

According to Carl, Bruce had come to see him on Friday to propose a deal. “Get rid of Bonnie this weekend,” Carl said Bruce told him. “I’ll pay you. I’m gonna be out of town. I don’t want nothin’ to do with it. Don’t tell anybody I had anything to do with it.” Bruce gave him $100, with the promise of depositing $350 more in his bank account on Monday, once the deed was done. There would also, of course, be the payout from the estate. (Bruce initially offered $500, but Carl, knowing his financial situation, offered to do it for $50 less. As Price would later put it, “Carl has not been accused of being very intelligent.”)

Bruce, Carl said, had been talking constantly about getting rid of Bonnie. “He was always saying, ‘Bonnie killed my son, she needs to suffer the way my son did,’ ” he told me. Bruce had taken in two of Jennifer’s granddaughters, and his money from the wheat field sale was going rapidly. “They ate out all the time, they got into online gaming,” explained Wilkerson, who obtained Bruce’s bank records during his investigation. “They were blowing through that money.” With about $20,000 left, and almost no other income to speak of, Bruce had grown nervous. According to Carl, he approached another potential hit man about killing Bonnie and Spinks but found the $10,000 asking price too steep. That’s when he’d settled on Carl.

A few hours after Carl’s confession, news reached Bruce that the investigation was tightening around him. He called Sheriff Brown. “Allen, I just got a phone call from my wife saying that she just got a phone call about you coming to arrest me, my brother, and her. And I said, ‘For what?’ ” Despite his protestations, he was arrested two days later, for criminal solicitation of capital murder, an allegation he pronounced “absolutely and totally ludicrous.” He vociferously contested Carl’s version of events. “First of all, I wouldn’t hire Forrest Gump to commit murder, you know what I’m saying?” he told a deputy. “Second of all, if I thought somebody needed killing that bad, I would take care of it myself.”

Investigators, however, had reasons to be suspicious. Bruce had grown brazen with his declarations around town. (“I just wish the old bitch was dead,” he told Les Dawson, a justice of the peace, at the courthouse. “I could get the money and go to Belize.”) It was also evident that, based on his six years on the Reno police force, Bruce knew the importance of a solid alibi, and he appeared to have carefully crafted his. In the days before the murders, he’d proclaimed to everyone he encountered—at the San Saba Printing Company, at the Corner Café, at J&J’s Tractor Company—that he planned to spend the weekend at John’s house, in Fort Worth, playing golf. (He did.)

Bruce, Carl, and Lillian were sent away to separate county jails, where they remained until Bruce’s trial this past April. (Jennifer was never arrested, and John escaped public scrutiny when he died of a heart attack three months after the murders.) At the trial, held in Burnet, Bonnie’s relatives and a handful of San Sabans watched as Bruce sat coolly through the proceedings, convinced there was nothing he’d be found guilty of. He wore a suit every day and furiously took notes, prompting one reporter to observe, “If one did not know Harkey, he could be mistaken for one of the lawyers in the courtroom.”

In exchange for a lighter sentence, Carl and Lillian agreed to testify against Bruce, and jurors also heard from two inmates, including one former Aryan Brotherhood member, who claimed that Bruce had tried to hire them from jail to kill both Carl and Spinks. The jury took one hour to find him guilty. “He genuinely thought he was fixin’ to get a not-guilty verdict,” recalled Spinks, who was present. “And when the jury read it out, his mouth dropped open and his shoulders dropped. He was floored.” Bruce was sentenced to life without parole.

The sentencing hearings for Carl and Lillian took place a couple of weeks later at the San Saba County courthouse. Carl, looking pudgy and sporting a large horseshoe mustache, nervously bounced his legs, his feet shackled, as he sat in his orange-and-white jumpsuit. He scowled as the judge read his sentence: life without parole. At her hearing, Lillian, her pale blond hair held back by a white scrunchie, sobbed uncontrollably. To comfort her, the sheriff handed her a cup of water, and her lawyer whispered, “You are making out better than anyone else in this, by far.” She received 45 years.

Afterward, one San Saban who’d witnessed all the proceedings expressed his town’s pleasure in the outcome. “We’re trying to figure out who Tommy Lee Jones plays in the movie,” he quipped, “if he doesn’t play himself.”

Bonnie was laid to rest next to Riley in the city cemetery on the afternoon of April 1—exactly 42 years after Eric Harkey’s birth. A day earlier, San Saba residents had attended a funeral service for Karen; now they crowded into First Baptist for Bonnie’s. Her closed casket sat in the sanctuary alongside photos of her with Riley and Miss Kitty. Betty Ann had provided a long pink dress for Bonnie to be buried in. She, like the three hundred other assembled mourners, was still reeling from the shock of her friend’s violent end. “We must not let death steal the memories of her joy in life!” Pastor Crosby exhorted the crowd.

Why hadn’t Bruce and Carl just waited? The question reverberated across living rooms, cafes, and hair salons around San Saba. Bonnie was ill, after all; they would have come into their inheritance soon enough. “She might have lived two years, or maybe five—but where is he now?” said Les Dawson, referring to Bruce and his future behind bars. Local columnist Lindy Lieban Schulz voiced the collective unease. “Our world has changed, and many people in it have become motivated by greed and grown up with a sense of entitlement,” she wrote in the News & Star on April 5. “Humans lose their hearts, their souls, and their ability to act like anything other than monsters.”

In August I went to visit Carl at the Telford Unit, in New Boston. He told me that the meth he’d done the day of the murders, as well as Bruce’s manipulation, were responsible for his crimes. “Bruce could con you into doing anything he wanted you to do,” he said mournfully in his prison whites. “I thought Bruce was my best friend. But he don’t care about anybody but himself.”

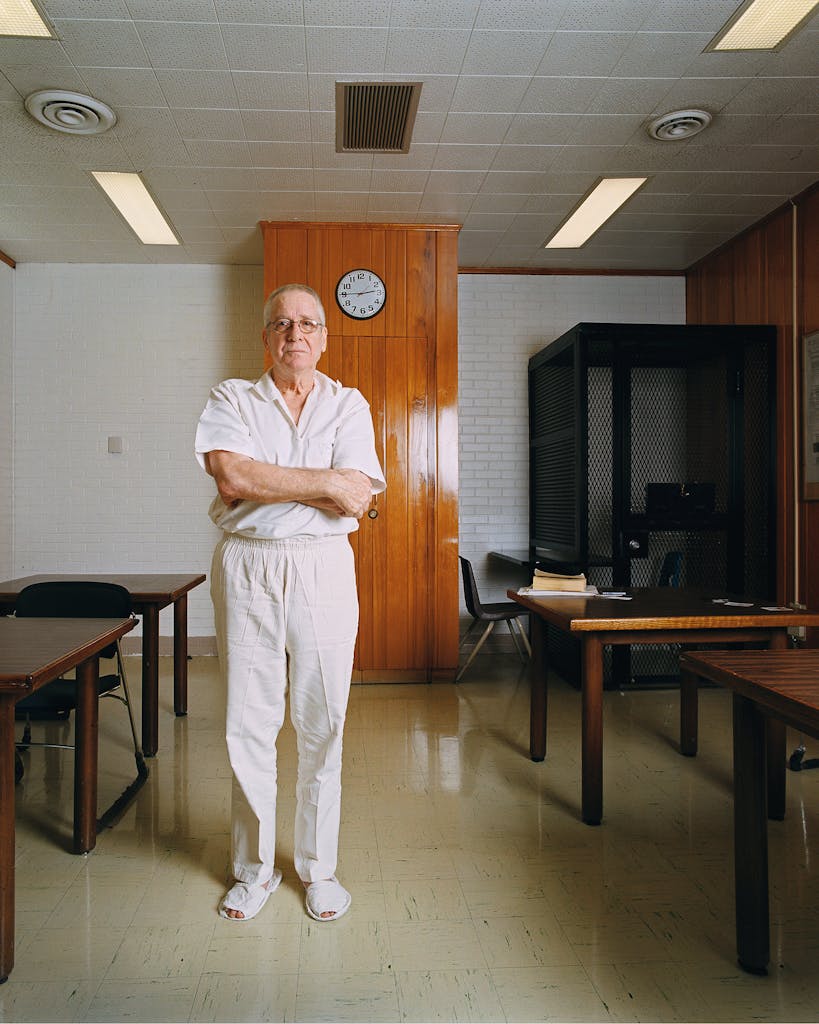

When I reached out to Bruce for his side of things, he sent me a letter. “The real story is of greed, corruption, love, hate, lies, and violence. And, I’m the only one left alive that knows the truth,” he wrote, his ballpoint indenting the paper. Shortly thereafter, I went to see him at the Byrd Unit, in Huntsville. His silver hair was closely shorn, per regulations, and he wore wire-frame glasses and flimsy terry-cloth slippers. Though he appeared physically diminished since his sentencing, his self-regard was intact. “Was I enamored with or happy about Bonnie Harkey? No, I never did like her, never did get along with her,” he acknowledged. But that didn’t mean he was responsible for her murder. “She was the closest thing to a mother I ever had,” he said, choking back tears.

He explained their animosity. “My grandfather assumed that if anyone were to take over the farm, it would be me. Because of that, Bonnie did pretty much everything she could to alienate me.” He was convinced she had caused Eric’s death. “Bonnie let the baby die because he was a threat to her, because he was the firstborn male heir to Harkey Farms,” he told me. “[The doctor] had given us explicit instructions not to feed this baby and put him down with nobody around.” (Bonnie’s niece Teresa contests this view. “Anything in this world that was wrong in Bruce’s life, he blamed Bonnie.”)

As for Carl, he was like a bad penny who kept turning up. “How is it, if I’m the mastermind, that I established an alibi before I planned the crime?” said Bruce. He’d openly shared his travel plans to Fort Worth, he continued, because he was excited to go to the big city. “I didn’t have anything to do with the death of Bonnie Harkey or Ms. Johnson,” he repeated. “Nothin’. If I waste my time and energy hating the people that have claimed I did, I’m takin’ away time from loving my wife and my children. And I won’t do that. All I wanna do is get this cleared up and go home.” He remains hopeful that his case will be overturned on appeal.

I drove to San Saba in late summer. The town has recently focused its energies on tourism, redeveloping its downtown, but the pecan industry remains alive and well. Everywhere I turned, I encountered the Harkey name: on a marker next to the courthouse, in photographs at my hotel, on Harkey Street. I made my way down U.S. 190, passing Harkey Pecan Farms and its rows of trees. Though the civil side of Bonnie’s estate was still being hammered out, Carl’s legal wife, Melissa Pafford, and their two children were set to move into the Harkey house, and it appeared that the orchards would be divided among them and John’s heirs. The Millicans, their lease having expired, were no longer caring for the orchards, and as I passed by the historic groves, the trees looked unkempt, thirsty from the drought and in need of a trim. Several of the older ones had died.

When I arrived at the historical marker for Harkeyville, I stopped the car. The marker stood in front of a metal storage building and across the way, a donkey grazed in front of a newly built house. As I got out to read the inscription, the property’s owner, a mustachioed 74-year-old named Larry Hibler, rode up to me on an ATV. “This was all Harkey before, the whole area,” he told me, stretching his hand out. His son had built the house where the Harkey blacksmith shop once stood; you could still find racing horseshoes whenever you dug in the dirt.

“But I’m the mayor of Harkeyville now,” Hibler continued. He paused, then gave a heavy sigh. “There aren’t any Harkeys left.”

- More About:

- Longreads

- Tommy Lee Jones

- San Saba