The Swingers Club

On August 11, 2004, readers of the Mineola Monitor, a weekly newspaper that serves much of Wood County, in East Texas, sat down to a familiar front page. “Area schools begin ’04 year next week,” one headline announced; “28th Annual Hay Show samples to be collected,” declared another. A photograph showed locals eating hot dogs at the Humble Baptist Church. “They braved the heat to enjoy music and good old-fashioned neighborly conversation,” read the caption.

Then Mineolans turned the page. Above the Community Calendar and next to the letters to the editor, they came to a story titled “Sex in the City,” in which regular columnist Gary Edwards revealed that a club for “swingers and swappers” was operating in town. The club was called the Retreat. There were twelve rooms, two hot tubs, a karaoke machine, a stereo, a big-screen TV, a sex swing—and a lot of beds. “We’ll do the operators of the facility a favor and we won’t say where it’s located for now,” Edwards wrote. “If they just move quietly out into the country . . . we’ll try and forget they’ve infiltrated our town with their set of moral standards.”

Swingers clubs are legal in Texas as long as no one is soliciting or paying for sex, and until Edwards’s column, the Retreat had been something of an open secret. It was located next door to the Monitor offices, in the former Mineola General Hospital, and its membership included locals as well as people from Tyler, Dallas, and Louisiana. The proprietors, Russ and Sherry Adams, lived just up the road in Quitman. On an average Friday they would host anywhere from fifteen to thirty swingers, most of whom the couple knew (the Adamses insist that the Retreat was not a club but an “on-premises party house”). “If we didn’t know them,” Russ told me, “they had to be known by other couples before they were invited to party.” Sherry would provide a snack buffet in the evening and then make breakfast burritos Saturday and Sunday mornings. “There are probably two hundred swingers within fifty miles of here,” Russ said. “It’s a lifestyle is all it is.”

Not, however, a lifestyle shared by the majority of the citizens of Mineola, a quiet town that’s home to 5,600 souls and a large number of antiques stores and Baptist churches. Edwards’s column about the swingers inspired more reader response than anything he’d ever written, and by early September, the party house was shuttered.

Things returned to normal, for about nine months. Then, on June 22, 2005, a woman named Margie Cantrell, who had moved to Mineola from California the previous year, showed up at the police station with a shocking story about the Retreat. Margie and her husband, John, were career foster parents who, after arriving in Mineola, had taken in four new kids. As Margie explained to the on-duty officer, one of her new foster daughters, eight-year-old Sheryl, had told her that she and Harlan, her six-year-old brother, had been forced to perform sex shows at the swingers club. (The names of all the children in this story have been changed.) The police couldn’t find any evidence or other witnesses, though, and the investigation was dropped.

Five months later, the case resurfaced in Smith County, Wood County’s neighbor to the south. This time the Texas Rangers were called in. And the stories got uglier: The kids had been taught “sexual dancing,” and they had been forced to have sex with each other at a “sex kindergarten” run by a guy named “Booger Red”; after “graduating,” they were made to dance, strip, play doctor, and have sex with each other at the club. The shows were videotaped, and in order to break down the kids’ inhibitions, they were drugged with Vicodin. According to the allegations, there were half a dozen adults involved in the sordid operation, including Shauntel Mayo, Sheryl and Harlan’s birth mother; Jamie Pittman, her boyfriend; and Sheila Sones, the kids’ maternal grandmother. Many of the accused had drug or alcohol problems and lived in rural Tyler. Though the swingers club was in Mineola, Smith County officials claimed jurisdiction because the alleged perpetrators lived there.

Investigators followed the case for a year and a half. Once again, no physical evidence or adult witnesses were discovered, but in July 2007, arrest warrants were issued for six people, including Mayo, Pittman, Sones, and Booger Red, a red-haired body shop sandblaster whose real name, Patrick Kelly, is rarely used, even by family. The salacious charges shocked East Texas. “6 INDICTED IN CHILD SEX RING,” screamed the Tyler Morning Telegraph’s front page. At the first two trials, held last spring, justice was swift and simple. Pittman and Mayo were each convicted in only four minutes, about the time it takes twelve citizens to stand up and raise their right hands in anger, and both were sentenced to life in prison.

The stories got uglier: The kids had been taught “sexual dancing,” and they had been forced to have sex with each other at a “sex kindergarten.”

But things were about to get a lot more complicated. Up in Wood County, a grand jury had launched its own investigation, prompted in part by local citizens demanding to know how an organized child sex ring could have run undetected for so long in little Mineola. And as the district attorney, Jim Wheeler, looked into the Smith County case, he began to have doubts. To begin with, Wheeler found out that back in 2005 two of John Cantrell’s former foster daughters, Sally and Chandra (not their real names), had accused him of sexually molesting them in California many years before. This information had never been mentioned during the trials of Pittman and Mayo. Wheeler also turned up more than a dozen swingers who went on the record with emphatic statements that there had never been any children in their party house. Wheeler later told me, “There was a total lack of corroboration for what those kids said happened.”

But Wheeler’s investigation had no bearing on the case being prosecuted 35 miles to the south. In Tyler, the kids’ testimony was enough, and the legal system marched on to the next defendant, Booger Red, who was convicted on August 21, 2008, and given life. By this point the story had gone national. “Trouble in East Texas,” Newsweek proclaimed. “A town is shaken by the saga of a child-sex ring.” Smith County assistant DA Joe Murphy summed up the feelings of many in the region and the rest of the country when he said, during Booger Red’s trial, “This case is about pure evil.”

That is the one thing, the only thing, on which everyone in this story can agree. But who are the victims? If Murphy and Smith County DA Matt Bingham are right, they are the children; if Wheeler is right, they are the defendants. How could the authorities in one county—the police, investigators, members of the DA’s office—arrive at such a different conclusion than the authorities in the county next door? Everyone looked at the same basic facts, saw the same interviews, and read the same reports, but Wood County found nothing, whereas Smith County found the worst child sex ring in Texas history. What really happened, if anything? The answers lie deep within a strange, winding story that covers two decades and two states and involves dozens of well-meaning adults and troubled children. We don’t yet know how the story ends; four more defendants are currently awaiting trial. But we know how it begins: with Margie Cantrell.

The Cantrells

Margie Easton met and married John Cantrell in 1975, when she was 25 years old. They had each already been married once and had three kids between them. Both were born and raised in California, though John’s parents were from the West Texas town of Olton. After marrying, the Cantrells settled in Vacaville, northeast of San Francisco, and had two children, Jacob and Jon-L. John was a carpenter, though a back injury kept him from working much. In 1985 the couple got licensed as foster parents and began taking in and adopting children. Their first three foster kids, all from one family, were Sally, Lorraine, and Bill.

The household grew quickly. John and Margie would usually have in their care more than ten kids and sometimes as many as sixteen. Some stayed for a short while, others for longer, until they were eventually adopted by the Cantrells. They were a religious family and became known for their willingness to foster kids with emotional problems. It was all for love, Margie would tell people. But it was also a livelihood; in 1991 foster families in California could receive up to $3,760 a month to care for a child with serious behavioral problems (Margie says the most they ever received was $1,400). Margie, who often homeschooled her kids, was tough on them; Lorraine recalls that her voice was frequently hoarse from yelling.

By the time they left California for Texas, in June 2004, the Cantrells had adopted 27 children, according to Margie, and fostered or otherwise assisted hundreds. Margie told me that they moved so that John could return to his parents’ home state—“We felt it was time to give Dad the chance to be where he wanted to be.”

They originally planned on settling in Tyler. “On the Internet, Tyler looks pretty, but then you go and it’s not that great,” Sally explained. “But we fell in love with Mineola.” Margie, John, and five of their young children moved into a five-thousand-square-foot house on Lake Brenda on the north side of town (three adult children, including Sally, rented a separate house). The following year the Cantrells were given group-home status, able to take up to twelve children. Their certification came through the Bair Foundation, a national Christian organization that finds and licenses foster homes for Child Protective Services, the state agency that investigates allegations of child abuse.

They had chosen to settle in an area where the need for foster parents was great. Poverty and drug abuse are growing problems in both Smith and Wood counties, and the narrative of neglect and abuse was all too familiar to local CPS workers. One family in particular was drawing a lot of attention. For about two years, caseworkers had been getting calls about Shauntel Mayo’s children. In November 2004, CPS received a tip that Sheryl, Harlan, and their four-year-old sister, Callie, were locked outside of their trailer in rural north Tyler while Mayo and her boyfriend, Jamie Pittman, were smoking crack inside. A CPS worker checked it out, but no action was taken. The family was a mess. Harlan and Callie’s father was in prison; Sheryl’s father was not in the picture. Mayo was a regular drug user who worked as a cashier and a maid and had a couple of arrests for hot checks.

About four months later, a social worker visited Mayo’s trailer a second time and found Sheryl and Harlan outside with a couple of pit bulls (by this time Callie was living with her maternal grandmother, Sheila Sones). There was little food, and the electricity had been turned off. CPS removed the children, who proved difficult to place in foster homes. Harlan was wild; at school he mooned others, and after he hit a couple teachers he was suspended. Over the next two months, they lived in three homes. Finally, on May 4, they were placed with the Cantrells.

Counting two other new boys, the Cantrells now had nine children. Sally had met and married a local man and gotten pregnant. Margie had not been pleased, but there was little she could do. Besides, she had her hands full with Sheryl and Harlan. When their CPS caseworker, Alexia Sirles, came by to check in two days after they were placed, Margie told her that Sheryl had been talking about “a boyfriend named Jamie that she has been dating off and on for some time,” according to Sirles’s report. At 25, Sirles was working one of her first cases for CPS, and she noted that Margie had a lot of experience dealing with sexually abused children. “She believes that [Sheryl and Harlan] are exhibiting several symptoms of sexual abuse,” Sirles wrote.

A week and a half later, Sheryl got an evaluation from Wilson Renfroe, a psychologist that the Bair Foundation had assigned to the case (it had also appointed a therapist and a psychiatrist). The girl said nothing to Renfroe about a boyfriend named Jamie, though the psychologist reported that she did say that her mother’s boyfriend was mean and that her mother had once touched her in an inappropriate manner. Renfroe also noted that “she told me she has difficulty telling the truth.”

Two days later, the case took a decisive turn. Acting in response to an “outcry” that the children had made to Margie, which Margie had duly reported, Sirles arranged for Sheryl and Harlan to be interviewed at the Child Advocacy Center (CAC) in Smith County. An outcry, in the parlance of child abuse investigators, is defined as the first disclosure that a child makes to an adult about being molested; it can be admitted in a trial even though it is hearsay (essentially, if a child tells an adult about being abused, that adult becomes a legitimate witness).

Sirles wrote in her report: “Worker met Mrs. Cantrell and the children at the CAC for a forensic interview. The interview was prompted because the children have been discussing with the foster parents ‘sexual dancing,’ and watching pornographic material with mom’s boyfriend. The children discussed having to play doctor on a ‘stage’ in front of men who paid money to see the show. [Sheryl] also discussed how she danced with her mother and two other women.” These were monstrous allegations, but Sheryl and Harlan would not corroborate them at the CAC. They said that no one had ever touched or looked at their privates and that they had never watched porn. “No pertinent information was discovered at the interview,” Sirles wrote.

During this time, Sheryl and Harlan were also seeing Greg Singleton, the therapist appointed by the Bair Foundation, once a week. Singleton is a clinical social worker at the East Texas Medical Center in Mineola. He talked to the kids about a wide range of things, from how they were sleeping to whether they got along with their new siblings. He also asked them about the allegations of sexual abuse, though it was not until June 22 that either of the kids said anything that would echo their original outcry. On that morning, according to Singleton’s notes, Sheryl “voluntarily and without prompting from me, stated that she used to have to dance with three other women (one of whom was her mother) on stage for crowds of men, whom she called ‘sickos’ without elaborating.”

Sheryl did not tell Singleton where the stage had been located, but just a few hours after the interview, Margie arrived at the Mineola police station to say that she had just come from the empty swingers club building, which she and John had been considering as a site for a group home. According to the police report, “Cantrell stated that while they were walking through, [Sheryl] began recognizing the rooms and started describing each one. Cantrell stated that she asked [Sheryl] if she had ever been in this building and she responded by saying that she used to dance here . . . she would dance toward the men in the audience and they would hand her money.” When the interview was over, Police Chief Jason Shanks and Detective Timothy Prince headed over to the swingers club building. They found no evidence to confirm Margie’s allegations.

Still, the officers took the stories seriously, and the next morning, along with FBI agent Jon Brody, they met Sheryl, Harlan, and Margie at the North East Texas CAC in Winnsboro, 26 miles north of Mineola, where the kids were interviewed by a social worker. Harlan bounced a ball and drew pictures, repeatedly denying that anybody had touched his privates or done anything to him. Sheryl was different. At first she just talked about an incident back in 2002 when her babysitter’s boyfriend had molested her. But then, for the first time, she began to recount to someone other than Margie events that had happened at the swingers club. She described a sordid world of dancing for money and food, playing doctor, and doing weird skits. In one skit, she said, the kids wore parachutes with ropes tied to their waists (which gave them wedgies). They got stuck in a tree and then came down. Jamie pretended to kill a dog or wolf puppet while Harlan pretended to kill a snake puppet—both of which were operated by a guy named Booger Red. The walls of the club had been covered with pictures of witches and dragons, Sheryl said, and six of the grown-ups had dressed in black witch outfits with white face paint. They had jumped out to scare Harlan when he danced “funky.” Their little sister, Callie, had to stay outside but their six-year-old aunt, Ginny (who is Sheila Sones’s daughter and Shauntel Mayo’s sister), was involved too. Videos had been made of the shows, but Jamie had burned them.

Prince, Brody, and a Mineola officer named Lucky Bolden drove to Shauntel and Jamie’s trailer to investigate. The couple denied having anything to do with the club and allowed the officers to search their home. The cops discovered a burn pile near the house but determined that it contained nothing more than building material. They watched some videotapes and found nothing. After that, the investigation was closed. “We felt there wasn’t any offense,” Prince wrote in a statement. Mark Taylor, then the DA of Wood County, told me, “It was everybody’s opinion that there was nothing there.”

The Smith County Case

The Mineola Police Department’s decision to close its investigation did not end the matter, in part because Margie would not let it die. She later told investigators, “I called Smith County, the FBI, and the Mineola police several times, as well as CPS, the Smith County CAC, and the Smith County police.” Sirles was also pursuing it. Upon first hearing the children’s allegations, she had notified her CPS supervisor, Kristi Hachtel, who passed the story on to Tiffani Wickel, an assistant district attorney in Smith County. Wickel knew all about Shauntel Mayo and Jamie Pittman. As the prosecutor overseeing Smith County’s CPS cases, she had been in charge of removing Sheryl and Harlan in the first place. Margie later said, “Tiffani Wickel I guess saw something in my heart, and she believed me and got right on it.”

What also helped keep the case alive were the kids’ ongoing interviews with Singleton and psychiatrist Donald Fulsom. On July 18 Fulsom contacted Sirles and told her that during his last interview with Sheryl, the girl had claimed that Mayo and Pittman had sexually abused her and Harlan. The following day, Sirles got another call, this time from Singleton, who said that Sheryl had told him that while living with Mayo and Pittman, she had been forced to “do dirty acts” and “have sex with her brother.” Singleton also reported that Sheryl had mentioned having to “strip” at “Booger Red’s house” and at “the yellow building that used to be a hospital in Mineola” and that she had been forced to take “funny pills” that made her act crazy.

Even more significant, Singleton said that in another session that day, Harlan had confirmed allegations of sexual abuse for the first time. According to Singleton, the boy stated that “his mother used to rub his ‘potty’ and ‘weiner’” and that “she ‘made’ him touch his sister’s genitals and the genitals of other children.”

That same month, both Callie and Ginny were also interviewed at the Smith County CAC. Sheryl had said that both girls had been involved in the sex ring, but now each denied knowing anything about the club—just as Sheryl and Harlan had done when first questioned. Nevertheless, three months later, CPS removed Callie from the home of her maternal grandmother, Sheila Sones, when Sirles got word of an outcry that seemed to confirm Sheryl’s story. Specifically, Callie had told her paternal grandmother, Virginia Mayo, that Ginny had been forced to dance with Jamie in front of men for money while Callie had “jumped” (later, at Pittman’s trial, Virginia Mayo explained, “I asked her if she knew how to dance, and she said, ‘No, Meemaw, I jump. Out of a cake, I jump’”). After this, on October 20, 2005, Callie was placed with her siblings in the Cantrell home.

It was a tumultuous time for Margie and John, for reasons that had nothing to do with the swingers club investigation. The previous month, Sally had accused her foster father of molesting her back in the late eighties. The DA’s office in Solano County, California, where Vacaville is located, had opened an investigation and contacted one of Sally’s sisters, Chandra, then 23 years old, who Sally said had also been abused. Chandra was reluctant to talk, but Texas CPS and the Bair Foundation were informed of the allegations, and a CPS caseworker named Rebecca Calvo was assigned to interview Sally and Chandra. According to Calvo’s subsequent report, both women affirmed the allegations, though Chandra again said she didn’t want to get involved. Calvo then questioned Margie and John, who denied the allegations. The Cantrells’ current children, including Sheryl and Harlan, were interviewed too. None of the kids made any outcries, and they were all allowed to remain with the Cantrells, though Calvo worried over the decision. She later wrote, “This worker has a number of concerns with foster children being placed in this home.”

Calvo’s apprehensions did not affect her colleagues’ confidence in Margie’s allegations. On November 3, at a hearing before a family court judge, Margie testified about what Sheryl, Harlan, Callie, and Ginny had told her about the sex kindergarten and the sexy dancing for money. Based on Margie’s testimony, Ginny was taken from Sones the next day and placed with a foster family in Palestine. Not long after, her new foster mother reported that Ginny had made an outcry in which she talked about wearing “strip clothes” with Sheryl, Harlan, and Callie and taking pills “to make [me] dance sexy for the boys.”

The case was getting bigger and more complicated. Wickel, who had been alarmed when she discovered that the Mineola Police Department had closed its case so quickly, felt the story required further investigation. She brought in the Texas Rangers. In mid-November, Sergeant Philip Kemp took over.

The Ranger

Kemp was a veteran officer of the Department of Public Safety and had spent eight years as a state trooper and eight more as a highway patrol sergeant. He had become a Texas Ranger a year and a half earlier and had been a chief investigator on only one child abuse investigation in his career. He would later state in court that he had never interviewed a child under ten, had no training in how to do a forensic interview with a child, and had never read a magazine article or a book on the subject. Nevertheless, on November 30 he interviewed Sheryl and Harlan at length.

During the session Sheryl added new details to the basic story she had been telling to Singleton, Fulsom, Renfroe, Margie, and the CPS and CAC caseworkers. She now said that eight kids had performed at the swingers club (previously she had said five) and that she had worn a pink skirt with blue glitter. She talked about a man who would announce, “Ladies and s-e-x people, here is the movie!” She told how Booger Red had once gotten mad at a woman and choked her and how a bunch of people ran out of a nearby church to see what the commotion was all about. During the interview, which Margie participated in, the children sat together at several instances, and Sheryl tried on occasion to coax the reticent Harlan into talking. At least a dozen times he denied knowing anything, but ultimately he too said he had been to Booger Red’s trailer, performed in the plays at the club, stripped, and taken “silly pills.” This was the first time that Harlan had affirmed Booger Red’s involvement.

Kemp was getting valuable new information, but according to experts I consulted, he was breaking fundamental rules for interviewing children. To begin with, he let Sheryl and Harlan be questioned together. “That’s really bad,” Elizabeth Loftus told me. Loftus is a distinguished professor of psychology, criminology, and law at the University of California at Irvine and one of the country’s foremost authorities in the study of false memories. “If they are together, you are not getting independent information. Each is hearing what the other is saying. You don’t know which is one’s story and which is the other’s.”

Kemp’s other questionable procedure, according to Stephen Ceci, a developmental psychology professor at Cornell University, was letting Margie sit in on the interviews—and indeed, sometimes lead them. “That is very improper from a forensic standpoint,” said Ceci, who is an expert in the field of children’s courtroom testimony. “He should have referred it to the CAC. They would never allow her to be sitting in the room. She’s involved in the case—she’s the outcry witness. Letting her sit there, the Ranger doesn’t give the kids an out to say, ‘No, it didn’t happen.’”

Kemp defends his techniques. In an e-mail he sent me in February 2009, he explained that the purpose of his interview was not to obtain additional information but to document by videotape what the children had said previously. “This was not a forensic interview,” Kemp wrote. “I had already been informed of all the information discussed in the interview. I just wanted it documented and I felt that if the children were at ease with Ms. Cantrell in the room they would open up and tell me what I had already been told.”

Margie is a stout woman, and in a video of the session, she can be seen looming over the children, stroking their hair and nodding at them as they look at her and talk. When Harlan covers his face with his hands, refusing to speak, she reaches over, pulls his arm down, and takes his hand in hers. Twice, when the children are incommunicado, Kemp tells them to just talk to Margie. They do, for minutes at a time, while Kemp sits quietly across the table. With Harlan, Margie leans across the table, her wide forearms just inches from the little boy’s torso, and asks, “Who video camera-ed?” Harlan says it was Jamie. Margie replies, “Let’s see, I don’t remember. Who else?” Harlan says, “Booger.”

As the investigation proceeded, Kemp made other questionable choices. He later admitted in court that he never went to Booger Red’s trailer, the site of the alleged kindergarten. He didn’t go to the club until nine months after beginning his investigation. And he never interviewed any swingers about the child sex shows they had allegedly witnessed.

In his e-mail to me, Kemp dismissed concerns that he had not investigated Booger Red’s trailer sufficiently. “A long time had already passed from the time the acts took place and the children were removed to the time I became involved,” he wrote. “It was felt that any evidence that would have been at the residence would not be present.” At Booger Red’s trial, he justified the delay in going to the club on the same grounds, saying that he didn’t go sooner because the crime scene, by that point, would have been compromised. As for interviewing any swingers, he testified that he had knocked on Russ Adams’s door several times but that no one had ever answered.

In July 2006 Kemp interviewed Harlan and Sheryl again, then he questioned Ginny. She repeatedly shook her head when asked about the sex kindergarten and the club, even after Kemp put Margie and then Sheryl in the room with her. An August interview with Callie was more productive. A year before this, during an interview at the Smith County CAC, she had not made an outcry. Now Kemp interviewed her with her new foster mother, Margie, in the room, and the little girl talked about Booger Red’s kindergarten, doing bad stuff in front of people, and taking silly pills. She described costumes (she was a witch, Harlan a bear, and Sheryl a ghost) and fantastic scenes.

“[Sheryl] would fly around,” Callie said. “I would fly around on a broom and [Harlan] would just crawl on the ground.”

Kemp asked her if she was on the ground or in the air.

“Air,” Callie replied.

Kemp asked how she got there.

“With my broom.”

Finally, in May 2007, almost two years after the Mineola Police Department closed its investigation into Margie’s allegations, Kemp brought his evidence before a Smith County grand jury. Sheila Sones, the siblings’ grandmother, was arrested first, in June, quickly followed by Shauntel Mayo, Jamie Pittman, Booger Red, and two others—Jimmy Sones, Sheila Sones’s ex-husband, and Dennis Pittman, Jamie’s brother, both of whom had been identified by Margie and the kids. All six denied having anything to do with a child sex ring. (Dennis Pittman’s ex-wife, Rebecca Pittman, was indicted in 2008 and also denied involvement.)

Kemp still had a few more loose ends to tie up. In January 2008, he interviewed Ginny again. Of the four young children, Ginny was the only one who had not yet confirmed the allegations to Kemp. During this interview, however, she finally did, though in a less-than-decisive manner. After Kemp had asked her questions for an hour—and she had denied having gone to the club or dressing up in costumes and dancing—he asked if she’d ever done a play in a building, with water around the stage and flowers on the wall. After a long pause, Ginny replied, “I can picture it.”

Kemp said, ”Okay, so you’ve been there before?”

“I think so,” Ginny said.

Kemp asked what she did there. “I think dance.” With whom? “I think [Sheryl], [Harlan], and [Callie].”

Two months later, in March, the first trial began. Jamie Pittman’s attorney, Jim Huggler, didn’t cross-examine any of the children for fear of alienating the jury. Joe Murphy, the assistant DA who prosecuted all three cases, hammered home the state’s main argument: Since, according to social workers and the children’s foster parents, there had been no contact between the two children in the Cantrell home and the other two kids during the period in which the initial outcry statements were made, they could not have “contaminated” one another’s testimony. This, Murphy told the jury, meant that their allegations were credible.

One of Murphy’s witnesses was Gayle Burress, a Tyler family counselor often called by the state as an expert in child abuse cases. Burress stated firmly that she believed the kids had been abused. “[Booger Red’s] kindergarten was the grooming spot,” she testified. “They had to teach them to dance. They had to teach them to touch each other and masturbate and take off their clothes and act sexy, because five-year-olds don’t act sexy, not if left to their own devices.” She also defended Kemp’s interview techniques, saying that nothing she saw indicated that the children had been coached or that their statements were contaminated. Interviewing children could be tricky, and she felt that Kemp had done a good job of making them feel “safe enough” to speak freely about their abuse.

Murphy’s star witness was Margie, who Kemp testified was “a caring and loving person.” On the stand, she talked about her long career as a foster parent for damaged children, saying, “I had to give up my life to do it.” She mentioned her and John’s plans for the old hospital building. “Well, this was kind of my dream,” she said. She also contradicted her statement to the Mineola police by saying that she and the kids hadn’t gone inside the club that day back in June 2005. When Murphy asked her, “Did you and the children walk from room to room?” she answered, “No.” A few moments later he again asked her, “Did you allow [Sheryl] and [Harlan] to walk through that building?” “No, no, no,” she answered.

Pittman’s verdict: guilty. Life in prison. Mayo’s trial took place two months later. Murphy’s case was largely the same as it had been against Pittman. Again, the children weren’t cross-examined. Margie assured the court, “They’re broken but they’re healing.” Justice was swift: The jury took just six minutes to sentence Sheryl, Harlan, and Callie’s mother to prison for the rest of her life.

The Wood County Case

Wood County law enforcement officers had been surprised when the Smith County DA brought indictments in a case that they had turned down. They had been horrified when they started getting angry calls from people wondering why they had failed to prosecute an organized child sex ring operating in the heart of Mineola. The nature of the case was particularly rankling, since Mark Taylor, the Wood County DA from 1979 to 2006, had made catching child molesters his number one priority. When he retired, the Tyler Morning Telegraph noted in an admiring profile that Taylor “can’t even begin to count the number of child molesters he’s prosecuted in 27 years.”

Current DA Wheeler insists that he is no coddler either. “This office knows how to prosecute child abuse cases,” he told me. Pittman’s and Mayo’s trials had received a great deal of media attention, and the way the story was being told—as a crime in Wood County that only the officials in Smith County had been righteous enough to prosecute—did not sit well with Wheeler. So in March 2008, the month that Jamie Pittman’s trial began, a Wood County grand jury began reexamining the allegations. One of the main investigators was police captain Joyce Box, a Mineola native, who had worked for eighteen years in local law enforcement and handled hundreds of sex abuse cases. From the start, she was skeptical about the swingers club. “When I started hearing about a bunch of kids doing these lewd things in front of a bunch of adults, I was suspicious,” she told me. “Sex abuse cases are one-on-one, done in secret. You don’t get an audience for them.”

Not long after starting the investigation, Wheeler stumbled upon the September 2005 allegations that Sally had made against her foster father, John Cantrell. The California case had been closed when Chandra refused to cooperate, but Box checked with the district attorney in California and received a go-ahead on her investigation. Then she called Sally. “She was waiting for someone to talk to her,” said Box. Now 28, Sally confirmed everything she’d said three years before. On May 9 Box interviewed Chandra, who confirmed the allegations. Box also spoke with Lorraine, who said she believed her sisters, who had been telling her these things for years. Box’s efforts soon prompted officials in Solano County to reopen their case.

Smith County investigators and officials inside CPS and the Bair Foundation knew about the allegations too. In fact, early in 2006, the accusations had led CPS to try to remove Sheryl, Harlan, and Callie from the Cantrell home, but according to a CPS spokesperson, the agency was “prohibited” from doing so by the family court. The fact that this information had not factored more heavily in the Smith County investigation was baffling to Wheeler. “The moment those California allegations became known to a public official in Texas,” he told me, “he or she should have paused and seriously considered them and their potential effect on the prosecution of these cases.”

In fact, the Wood County investigation was turning up all sorts of evidence that called into question the Smith County case. To begin with, Box talked to several of the swingers who had been present at the Retreat. According to a Mineola police report, one of the swingers, Roxane Storms, told Box that everyone who went in the place was carded and that absolutely no children had ever been present. Box also interviewed Russ Adams, the proprietor, who told her that his wife, Sherry, had already talked with three investigators from Smith County. The three were Kemp (who had been transferred to San Angelo but was still helping with the investigation), Ranger John Vance (Kemp’s replacement), and Todd Thoene, the lead investigator from the Smith County DA’s office. There is some disagreement about exactly when the interview took place. Vance later testified that it was “during the first trial,” in March 2008; Sherry claimed that it was in late May; Kemp told me that it was “after one of the first trials.”

Regardless of when it was done, the interview would become the most controversial aspect of the Smith County investigation. In an affidavit she gave last August in the trial court in Tyler, Sherry swore that she told the investigators that she had never seen any of the defendants and that she knew nothing about the alleged sexual abuse. “Ranger Kemp told me that when this whole thing was over that I would be in jail with the rest of them doing life,” she claimed, “because he knew what had happened in my establishment.” Still, Sherry said that she told the officers unequivocally that there had never been any children at the Retreat. In the affidavit, she also stated that the interview had been taped by both Kemp and Vance. Kemp wrote me: “I did not record anything . . . I don’t know if John Vance recorded the interview.” Vance said: “It was audio-recorded. There was one recorder in there.” However, no report was written, meaning none of the defense attorneys had heard about it.

Wood County investigators also found a transcript of Sheryl and Harlan’s May 17, 2005, interview at the Smith County CAC in which they’d said that they had not been abused—an interview that had not been seen by defense attorneys. Everywhere investigators looked, they seemed to find reasons to doubt Margie’s original story. “There’s no physical evidence that puts those children in that building,” Wheeler told me. “There are no witnesses that can ID those children as having been in that building—or any of the people on trial in Smith County. That building is fifty yards away from the highway, next to the newspaper, a mercury light in the front and back, in a neighborhood populated by cops, across the street from a nursing home, where people spend a lot of time looking out their windows—and you’re going to tell me and the forty-five thousand people of Wood County that no one saw any kids?”

The Trial of Booger Red

On June 18, three weeks after Shauntel Mayo’s trial, officers from the Wood County sheriff’s office carried out an arrest warrant for John Cantrell issued by the DA’s office in Solano County, California. Booger Red’s attorney, Thad Davidson, immediately asked for a postponement of his trial. The judge, Jack Skeen Jr., who was previously the longtime DA of Smith County, agreed, though he warned that the California charges would not be allowed into his court. Davidson, an ex-Marine, had been hired by Booger Red’s mother, Linda, who cashed in her 401(k) to make sure her son got more thorough representation than Pittman and Mayo had.

Davidson next tried to get the trial moved. “In no way do I feel my defendant can get a fair trial here,” he told KETK reporter Tamara Jolee. Davidson believed strongly in the innocence of his client, a married father of one with no criminal or CPS record. In fact, after the charges had been made, CPS had done an investigation in advance of removing Booger Red’s sixteen-year-old son, Steve, known as “Boogie” (he was placed in a group home in Dallas). The social worker interviewed a dozen friends and family, none of whom had ever seen or heard of children dancing or stripping at Booger Red’s trailer. Kids were always around, they said, but they were riding trikes and playing hide-and-seek.

Another thing that convinced Davidson was hearing from James Wood, a professor of psychology at the University of Texas at El Paso. Wood is a nationally recognized researcher on interviewing children who has closely studied the cases of ritual abuse that swept the nation in the eighties and early nineties. Those cases often featured accusations of devil worship and child sex abuse that were later discredited after it was revealed that the children had been implanted with false memories. Wood thought the Mineola case seemed to share certain characteristics with the most famous of the ritual abuse cases, the 1983 McMartin Preschool case, in Manhattan Beach, California. After a mother told police that her toddler had been abused at the day care, other parents brought forward their own children and soon there were 321 counts of child abuse against staff, as well as allegations of cannibalism. The first trial ended in a deadlocked jury, but prosecutors pushed on with a second one, which ended in a mistrial 28 months later. At the time it was the longest, most expensive criminal trial in American history.

Wood contacted Davidson, who sent him affidavits and police reports. “Reading them,” Wood told me, “it became apparent that the investigation had the classic features of a bogus case: many victims, many perpetrators, a lack of solid physical evidence, bizarre stories, highly improper and suggestive interviewing, children being pressured by adults to make allegations, and major inconsistencies and contradictions in the statements.”

Wood pointed out that at first, the kids had repeatedly declined to confirm anything about the club or the kindergarten. “We know that eighty to ninety percent of sexually abused kids who are formally asked about the abuse will report it,” he said. “Yet every single child in the Mineola case denied it when first interviewed by the official investigators. Only later, after repeated questioning, sometimes extending over several months or even years, did the children begin to allege sexual abuse.”

By this point Wood had volunteered to work on Booger Red’s defense for free. He helped Davidson develop questions for Kemp and helped Davidson’s co-counsel, Tina Brumbelow, on her cross-examination of the children. During the trial she questioned all four kids. Sheryl was on the stand for nine hours. She said that fifty videos and twenty costumes had been burned in the fire pit in front of Booger Red’s trailer, which she had visited more than sixty times. She said that Jamie had shot a dog and hanged some chickens and that Sones had cast spells from a spell book. Harlan testified that he had to do “bad stuff” with his mother. Ginny also used the phrase “bad stuff,” and when Brumbelow asked what that meant, she said, “Stuff nobody wants to hear about.” Like what? “Sexual harassment.”

Kemp was on the stand for three days. He defended his interviewing techniques, saying he’d used “common sense” and techniques he’d seen other forensic interviewers use. During the second day of questioning, Davidson learned of Sherry Adams’s interview, in which she said that no children—and none of the defendants—had ever been in her club. Believing that this was exculpatory evidence, Davidson moved for a mistrial, arguing that the defense should have been given this crucial information earlier. Murphy denied knowing about the interview, even though it had been conducted in the office of his lead investigator, Todd Thoene. Murphy told Judge Skeen, “We didn’t even know that any of this existed.”

Skeen called a hearing. Kemp was asked why no report had been written and replied that he hadn’t written one because he was no longer on the case; Vance said he hadn’t written one because “Philip Kemp advised me that [there] was no information that was gained from what he had already interviewed or had already developed.” To Davidson and other defense attorneys, it seemed as if the prosecution had been caught hiding evidence that could have proved the defendants’ innocence. Or, as Tyler attorney (and secretary of the Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association) Bobby Mims told me, “In my thirty years of practice, I’ve never seen anything like that—an absolute, honest-to-God frame-up.” When I asked Murphy about it later, he dismissed Mims’s concerns. “There was no type of frame-up in these cases,” he wrote me in an e-mail. “The defense attorneys were given everything that was in the possession of the Smith County District Attorney’s office.”

Judge Skeen denied the mistrial motion, and the trial continued. Davidson had three swingers testify that neither the children nor any of the defendants had ever been inside the Retreat. “Nobody brings a child in there,” said Roxane Storms. “Nobody.” He had Booger Red’s wife explain to the jury that there’d never been a “sex kindergarten” at their trailer. Booger Red himself took the stand and spoke softly in a thick accent. Jurors would later say they were surprised by how well he came off. He said he’d never been to the Retreat or trained kids to do sex shows . He knew Mayo and Pittman, who would come over on weekends with their kids. “We’d barbecue and let the kids run around the yard,” he told the jury. “We’d play country music and dance in the living room.” As for the allegations, he denied all of them, testifying, “I never touched these children.”

In Murphy’s closing argument he passionately reiterated the state’s case. “How is it,” he thundered, “that all four of these children—who had no contact with each other—are saying the exact same thing?” The jury took less than two hours to find Booger Red guilty of organized criminal activity. Like Pittman and Mayo, he was sentenced to life in prison. Afterward, jurors said that it was the children who had made up their minds. “The entire jury panel was breaking down in tears,” juror Todd Ressel said. He added, “Each time we had to make a decision, we all stood up and said a prayer, all twelve of us.”

Tyler defense attorneys were in shock. “I don’t mind a rough case,” Mims told me. “The prosecutor can hit hard, but he has to stay within the rules. I’d give him the benefit of the doubt up until they were given copies of the Adams statement. They had to have known they were prosecuting an innocent man.”

Both Murphy and Smith County DA Matt Bingham vehemently disagree, pointing to independent corroboration of the same things by all four children in their initial outcries. “The children had no unsupervised contact with one another,” Murphy wrote me. “Yet they all told of the same experiences. They named the same defendants.”

There are, however, some discrepancies in the kids’ initial outcries. Sheryl and Harlan’s outcry, to Margie, in May 2005, concerned “sexual dancing,” watching porn, and playing doctor on stage. Callie’s outcry, to her grandmother, in October 2005, described her jumping while Ginny danced with Jamie for money. Ginny’s first disclosure was to her original foster mother in November 2005 and concerned wearing “strip clothes” with Sheryl, Harlan, and Callie and taking pills. All the children eventually added to their stories, in ways that seemed to corroborate one another, but their initial outcries were by no means identical.

As for whether the outcries were truly “uncontaminated,” Callie’s statement that she had “jumped” while Ginny danced for money was reported by her grandmother, Virginia Mayo. But Mayo testified at Pittman’s trial that by that point she had already heard about the other kids’ allegations from Sirles. In fact, Mayo had specifically asked Callie whether she had danced, and only then had Callie started talking. “This is a particularly unreliable form of hearsay,” Wood, the UTEP psychologist, told me. “Statements reported by untrained adults who conducted suggestive interviews of children without keeping a recording of exactly what they asked and exactly what the children said.” These same qualms could apply to Ginny’s initial outcry, which was made to her first foster mother, who also asked leading questions about what Ginny wore and what the pills tasted like.

We also know from Sheryl’s testimony at Booger Red’s trial that she and Ginny were “best friends” who had talked on the phone three times a week for the previous four years. Psychologist Ceci said, “In the ritual abuse cases, by the time the kids’ testimony got downstream, to trial, it looked impressive, because all the kids said roughly the same thing. But if you look upstream, you find that they were really of different minds when first questioned. It may be due to cross-contamination that they started to say what their friends, siblings, and parents were saying.”

Bingham is sticking by the children. “I can unequivocally state that thirty-six jurors heard the evidence in three separate trials, and all believed the testimony of the children, finding each defendant, including Patrick Kelly, guilty beyond a reasonable doubt and deserving of a life sentence,” he wrote to me. “I have and will continue to stand by the conclusions reached by these Smith County jurors.”

Margie

Last November I knocked on the door of the dark-brick Cantrell home on private Lake Brenda, in Mineola. There were four cars in the driveway and a pool out back. A teenage boy answered, eating a popcorn ball. I gave him my card just as he was joined by John, who’s tall and looks like Santa Claus. I asked to speak with Margie. They disappeared, and a minute later the boy came back: “She says she has a lot to say but that her lawyer won’t let her talk to journalists.”

Since Margie would not speak to me, I spent the next five days in Mineola and Tyler looking for someone who might be able to tell me about her. Most of the dozen people I found would talk only if I assured them that I would not use their names. “Margie is very dramatic,” a reporter who had covered all three trials explained. “People in Mineola kept telling me they didn’t want to talk about her because they say she fabricates stories.” Gary Edwards, who wrote the column about the swingers, was one of the few people willing to let me use his name. “I’m not convinced that what was said to have happened up there really happened,” he said. “It all comes from one person, and I don’t have a lot of faith in her as a human being.” The first time Edwards met Margie was when she came into the Monitor offices alleging that the high school football coaches were abusing the kids. “She thinks a football coach hollering at a kid is child abuse,” he told me. “I’ve been around that program for twelve years—if actual abuse was taking place, I’d hear about it from the parents. I soon learned from people in the community that she has a propensity for stirring things up and getting herself stirred up, flying off in all directions with comments and accusations.”

This picture was at odds with the way Margie had been presented during the trial, but I wondered if the Mineolans simply didn’t know Margie that well, having lived alongside her for only four years. So I also contacted a dozen people in California and other states who had known Margie for decades. The picture that emerged was of a paradoxical, larger-than-life figure. To some she was “supportive” and “awesome,” to others “manipulative” and “controlling.” She had led dozens of children out of neglect and despair—and put others through staggering emotional and physical torment. According to her original three foster children—Sally, now 29, Lorraine, 25, and Bill, 27—Margie kept the kids in line through fear, humiliation, and violence, slapping them in the face, pulling their hair, throwing them against the wall, and slugging them in the stomach. Bill said, “It wasn’t always that way. When I was young, there was genuine love. But the older we got, she started bringing in more and more kids. She got overwhelmed with trying to care for all those kids.” John Cantrell’s son from his first marriage, Aaron Cantrell, now 40, could not speak to the violence but said, “I don’t think she has any business dealing with kids. It’s ironic that she’s in charge of foster children when she has such an extremely volatile temper.”

The kids also told me that Margie used to invent stories. Kelly Cantrell, John’s daughter from his first marriage, said, “Margie convinced all of us kids of whatever crazy idea she needed us to believe or buy into at the time, and you better not contradict her or there would be hell to pay.” Bill described her as “the puppet master.” “She brainwashes the kids to believe the stories she makes up,” he explained. Bill, Lorraine, and Sally all told me about the time when Margie gave their sister Veronica a black eye by punching her in the face—and then blamed it on Veronica’s running into a doorknob. “I saw her do it,” said Lorraine. “Then Margie and Veronica went into a bedroom for thirty minutes and came out laughing. Margie called everybody together and told us that Veronica had run into a doorknob.” Bill told me, “Veronica was too tall to have done that, but Margie convinced all of us kids that she had. Even Veronica was convinced.” California CPS often investigated the Cantrells, though nothing ever came of it. “CPS would talk to us,” Sally recalled, “but we were all brainwashed—too scared to say anything.”

I got drug into this real deep, all because they knew my name, all because of ‘Booger Red,’” he said bitterly.

However, I also found children of Margie’s who said the exact opposite. One of them was 29-year-old Laura Parker, who now lives in the Dallas area. She told me she had been a homeless teenager in Vacaville when the Cantrells took her in and became her guardians twelve years ago. “They’re awesome,” she said. “I wouldn’t be able to have a normal life if I hadn’t had their example—how to be married, how to show affection.” I asked her about the allegations of brainwashing and physical and emotional abuse. “Absolutely not true,” she said. “There’s a lot of resentment and jealousy from those kids. They’re angry inside, looking for someone to blame. This is a couple who has taken in kids that come from the worst of situations.”

Jon-L Cunha, one of Margie and John’s two biological children, is another avid defender. “My parents are good parents,” she told me. “They’ve always been there for us, always made sure we had everything we needed. We were always happy.” She also didn’t understand why Sally, Bill, and Lorraine were saying those things. “These kids have very psychotic emotional problems.”

In a case that has polarized so many people, it was fitting that the central figure, Margie, would be so divisive. In February, I finally spoke with her myself. Even after all the terrible things I had heard, I found Margie charming. She laughed easily, cried when I brought up what Sally, Lorraine, and Bill had said, and was firm about never having resorted to physical violence with her children. “That’s just talk. I don’t punch kids in the stomach until they can’t breathe. I don’t hit them. I didn’t even spank my kids except a couple of times. Those allegations are absolutely just hate. [Sally] was never hit a day in her life. Lorraine was absolutely cuddled.”

Bill, she said, had “a personal vendetta” against her and her natural son Jacob. But why? “They’re bipolar,” she explained. “Their mother’s a schizophrenic. They were broken in the beginning. Their dad used to stand Bill up against the wall and shoot guns at him and drown and revive him. The stories they’ve told are unmerciful.”

All three children deny being bipolar. “Everyone that’s against her is bipolar,” Lorraine told me. They also deny telling Margie horror stories about their birth parents. Bill told me that he has seen the county records explaining why he and his sisters were removed from their home. “It was for neglect,” he said. “There was no evidence of guns or drowning.”

As this story was going to press, Margie called with some news. “Everyone’s trying to figure out what’s really going on with [Sally], Billy, the whole bunch of them,” she told me. “Why do so many people hate Margie?” Now she knew. She said that a friend had forwarded her a few e-mails between various people, including Bill; Lorraine’s husband, Paul; and someone named John Johnson who Margie said had been making false claims to CPS about the Cantrells since 2007. “I can’t let you see them,” Margie said, “but it’s all spelled out so perfectly. Oh, my gosh! You can’t even begin to understand the hate of man! These people made us live in hell, they called me Satan, they called me monster, they called me everything.” She began to cry. “But I understand now why they did it.”

She couldn’t tell me any more, though she said she had already called Murphy’s office and left a message and that next she was going to the feds. “Just like I marched into that dadgum police department when I found out they hurt those babies,” she told me, “I’m marching into the FBI today.”

Booger

On February 9, 2009, Solano County district judge Peter Foor dismissed the sexual abuse charges Sally had made against John Cantrell because they fell outside the statute of limitations; she had waited too long to make a formal complaint. Shortly after the verdict, I asked John if he felt vindicated. “Oh, yeah,” he told me. “The judge read the whole thing, every statement.” He and Margie now have permanent conservatorship of their five Texas children (Sheryl, now 11; Harlan, 10; Callie, 8; and two others), a fact that still bothers Wood County DA Jim Wheeler. “When it comes to who is going to be a foster parent in Texas,” he said, “from a DA’s point of view, it is not appropriate for a person who has been investigated for a sex crime to be a foster parent.”

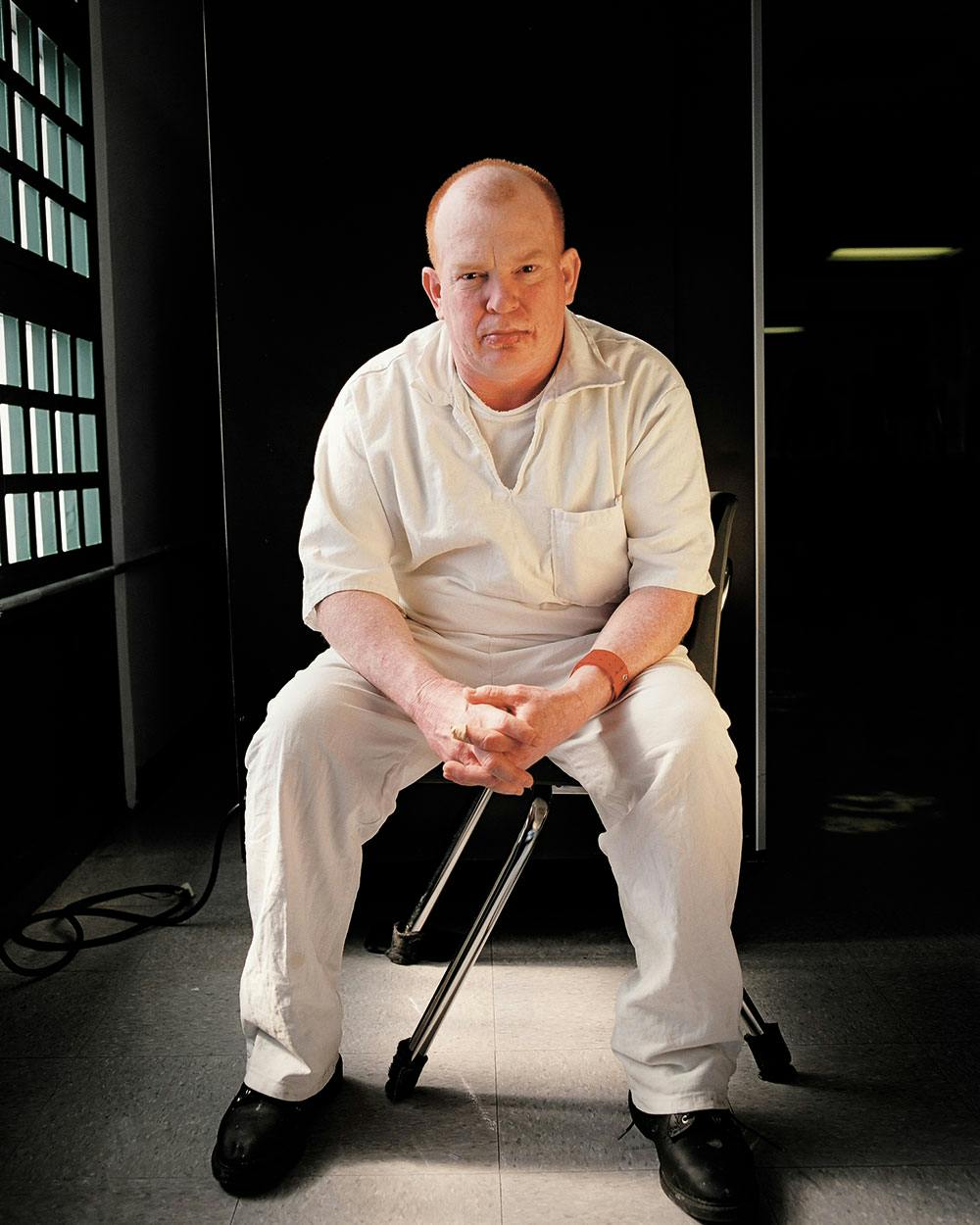

That same week I paid a visit to Booger Red at the Clements Unit, in Amarillo. Except for the time he drove his mother to visit his sister in El Paso, the prison is the farthest from Smith County he’s ever been. “It’s a long way from home,” he told me from the other side of the glass in the prison visiting room. His eyes were wary and his red hair thinning and fading. I told him that Willie Nelson was also known to his childhood friends as “Booger Red.” “I didn’t know that,” he said, smiling for one of the few times in our visit.

He described his old life, working a series of jobs like cleaning floors, hauling scrap iron, welding, and sandblasting. In his off-hours he liked to drink beer and talk about cars. He knew Jamie Pittman because they had grown up along the same rural road. They weren’t best friends, but they did hang out a couple of times a month. “I got drug into this real deep, all because they knew my name, all because of ‘Booger Red,’” he said bitterly. As for the other defendants, he insisted that he had met Sheila and Jimmy Sones only once or twice and that prior to his arrest he’d never met Dennis Pittman.

I told him that a few months earlier, around Thanksgiving, I had gone to see his trailer. The brushy plot of land where it sits, which has been in the family for three generations, is also home to his mother, Linda, and a niece and nephew of his. Linda had given me a tour, and I recounted to Booger Red the conversation we’d had. “I tell you,” Linda had said, “if there was something fishy going on, I’d have known. I used to work at Brookshire’s, now I work at Wal-Mart, different shifts, different times. The thing is, if he wasn’t working, he was home. Every weekend night he would be out here, barbecuing, drinking beer.”

It made Booger Red happy to hear about my visit. I said that I’d met some other members of his family, and that they had all been perplexed that anyone could think that their Booger had been the mastermind behind a child sex ring. “He’s a hillbilly,” his sister-in-law had told me. “I’d get ready to take his picture and he’d bend over and show the crack of his butt. He’d come home from work, hang out outside for a bit and talk to people. At a certain point he’d go inside, grab a beer, get in his recliner, take off his boots, and watch Deal or No Deal. That’s how he was.”

Booger Red smiled at this description. “That was me,” he said. “That was my day.”

He sat behind the glass in his prison whites, rubbing his hand over his forehead. How he got from that life to this is still a mystery to him: “At first I thought, ‘I ain’t done nothing, I ain’t got nothing to worry about.’ I was forty, had never been arrested. Why would a man my age all of a sudden start doing something like that? It makes no sense. I feel the same way most people do about those kinds of allegations. I just wish people would stop and look at what was said.”