This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

They say it was hard for anyone to dislike Benny Binion, unless, of course, Benny had his gun in that person’s ear and was in the process of blowing that person’s brains into West Dallas, which Benny was known to do when displeased. Even then it was nothing personal, just business. The man had thousands of friends, a fair number of enemies, and the good sense to tell the difference.

Benny Binion lived the first half of his life in Texas and the last half in Las Vegas and became a legend in both places. They called him the Cowboy, for reasons that had to do with guns, not horses. He was maybe the most popular gambler in America and certainly one of the few ever cast in bronze. There is a larger-than-life statue of the Cowboy near the rear entrance of Binion’s Horseshoe Hotel and Casino, the no-limit, no-frills gambling joint in downtown Las Vegas that Benny opened in 1951 and his family still owns.

The Cowboy was as generous with friends as he was malevolent with enemies. Politicians, judges, cops, entertainers, rodeo cowboys, robbers, and pistoleros from Dallas to Vegas owed him debts of gratitude, and sometimes debts of hard cash, which Benny was inclined to forget, rationalizing that if somebody owed him money it was his own damn fault. For Benny’s eighty-third birthday party, in November 1987, 18,000 friends and admirers showed up. The crowd included Willie Nelson, Hank Williams, Jr., Gene Autry, Dale Robertson, and other celebrities and underworld characters.

Though Benny claimed that he never went to school a day in his life, never learned to read or write, to multiply or subtract, he knew about numbers. He wasn’t much of a gambler himself, but he became, in the idiom of the trade, “a square craps fader,” square meaning honest and fader being the one who covers the crapshooter’s bet. He learned his lesson early, from an old-time Dallas racketeer named Warren Diamond, who operated a no-limits craps game in the twenties in a room at the St. George Hotel, near the Dallas County courthouse. Benny worked for Diamond, parking cars and running errands, and he never forgot the day that an oilman from Texarkana threw an envelope on the line and said, “Diamond, I’m gonna make you look.” Diamond gave the oilman a glance and said, “Pass him the dice,” meaning that he didn’t need to look, that he was ready to cover whatever amount was in the envelope. The oilman crapped out in two rolls, and Warren Diamond opened the envelope and counted out 170 one-thousand-dollar bills. The margin favoring a craps fader is small, something like 1.4 percent, but in the long run that fractional edge can make a fellow rich. By the time Benny died in December 1989, he was worth at least $100 million.

Benny had a talent for knowing exactly who and where he was and for sensing when it was time to fold his hand and go home. If his son and grandson had inherited this talent, they wouldn’t be facing federal racketeering charges today.

Benny was a product of turn-of-the-century Texas, when gambling was an accepted occupation and killing was a proper way of settling things, Old West style. It was an era that placed enormous value on individual initiative. The moral collapse that started with Prohibition and accelerated into the Great Depression made criminals out of people who were not otherwise inclined, fostering a disdain for law, an obsession with betrayal, a willingness to do almost anything to get by. The mind-set of the times was compressed in a saying that Benny repeated all of his life: “Never holler whoa or look back in a bad place.” When Benny thought of the Depression, he thought of what his pal Red Nose Kelly said one Thanksgiving Day when the bartender at the C&W poolroom asked him what he was thankful for. “Chili’s a dime and I still like it,” Red Nose replied straight off.

Born in Pilot Point in Grayson County in 1904, the son of a layabout who drank up the family inheritance, Benny left home at fifteen, bumming around El Paso and the Dallas–Fort Worth area, punching cattle, trading horses, gambling, bootlegging, getting in a little trouble but nothing he couldn’t handle. Toward the end of World War I, Benny settled in Dallas, apprenticing himself to Warren Diamond. Seldom had ambition and opportunity been better matched.

Despite the smug, pious, self-righteous image that Dallas had courted for the past half-century, there has always been a lascivious twinkle in the old girl’s eye. For most of her history, in fact, Dallas was a wide-open town. Her power daddies in the thirties and forties, particularly downtown bankers Bob Thornton and Fred Florence, not only tolerated vice, they competed with Fort Worth publisher Amon Carter to see which town could be the most wicked. Dallas landed the 1936 Texas Centennial celebration because of its reputation as a swinging town.

Though gambling was technically illegal, the systematic revenues it generated helped sustain city government and, in a curious way, helped forestall corruption. Bribes in Dallas during Binion’s reign were infrequent, usually in the form of personal loans to cops whose families had fallen on bad times. The true unit of exchange wasn’t money but information and influence. Benny wanted a rival shut down, he called Sheriff R. A. “Smoot” Schmid or deputy sheriff Bill Decker, his longtime friend and the lawman who really ran Dallas for most of three decades. Decker wanted some character run out of town, he called Benny. Rather than bribing individual cops, Binion and other gamblers cheerfully paid regular fines. Two times each week, an officer from the vice squad visited all the gambling houses and did a head count of customers. The next morning the gambling-house operators, or their attorneys, marched down to city hall, pleaded guilty, and paid fines of $10 a head. The charade was basically a taxing and licensing procedure, the perfect compromise between the dictates of piety and the doctrine of laissez-faire.

During World War II, there were 27 casinos in downtown Dallas and no telling how many whorehouses. Every weekend thousands of troops poured into town. “The downtown bankers and the big law firms believed that having an open town was patriotic,” recalls Will Wilson, who became the district attorney of Dallas County at the end of the war. In this milieu, Benny Binion was bound to succeed, his business being the city’s pleasure and vice versa.

Benny cut ties with his mentor, Warren Diamond, in 1926 and opened his own permanent craps game in room 226 of the Southland Hotel, just west of the Adolphus in the heart of downtown. Challenging a racketeer like Warren Diamond was a bold move for a 22-year-old, but it was exactly the sort of risk that energized Benny. He’d get a glint in his cool blue eyes, a sort of hard edge that told adversaries he was coming through, like it or not; Diamond was either too wise or too old to challenge his protégé. The Southland, owned by Galveston mob boss Sam Maceo, became the headquarters for Binion’s gang, known as the Southland Hotel Group. In 1928 Benny expanded his business to include the numbers racket, also known as the “policy” business. When Diamond killed himself in 1933, Benny became king of the racketeers.

Benny allowed other gamblers to operate craps games for a 25 percent cut of the action, but where the policy racket was concerned, he enforced a monopoly. Even during the Depression, the policies netted hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. The Southland Hotel Group ran several different policy “wheels,” so called because winning numbers were drawn lottery style twice daily from wire-mesh wheels; the world “policy” was there to suggest that a ticket was in some way insurance. Most customers were poor blacks from the Fair Park and the South Dallas areas, playing their hunches and dreams. Benny distributed free booklets on dream interpretations and gave the wheels fanciful names like the Harlem Queen or the Horseshoe. Benny’s gang kept 80 percent of the take and paid out the other 20 percent to the lucky winners.

Since runners picked up and delivered sacks of cash twice daily, employee theft was a big problem. Hard times called for hard measures. Benny once poked a pencil through the eye of a runner who held out on him. The bullet-riddled bodies of policy runners were found from time to time beside railroad tracks or in fields of weeds near the Trinity River bottom, but the lawmen didn’t bother to investigate.

For the most part, Benny was generous to his employees and considerate of his clientele. When a Jewish immigrant lost his dry cleaning business and everything else playing the numbers, Benny arranged for him to receive a modest lifetime pension. At Christmas the Binion gang passed out turkeys to regular customers. Not long before Benny died, some aging Dallas blacks, in Las Vegas for a class reunion, stopped by the Horseshoe to pay their respects to the Cowboy.

King of the racketeers was a title that had to be defended almost daily. The rule was, Do your enemies before they can do you, and Benny often found it necessary to arbitrate business differences with a .45 automatic. Murder was also technically illegal, but in the spirit of those times it was usually easier to beat a murder rap than to get exonerated for breaking and entering. Officially, Benny was charged with only two homicides, a black rumrunner named Frank Bolding, who was gunned down in Benny’s back yard in 1931, and a rival racketeer named Ben Frieden, who was ambushed in September 1936 as he waited in his parked car on Allen Street for a policy pickup. The area of Ross and Allen was the heartland of Benny’s territory. Killing Bolding was how Binion got his nickname; when the rumrunner charged at him with a knife, Benny tumbled backward from the crate where he had been sitting and came up shooting, cowboy style. Benny got a suspended sentence for that killing. An accommodating district attorney ruled that Frieden’s murder was self-defense, Benny having had the foresight to give himself a flesh wound before the cops arrived.

The danger to high-stakes gamblers was from robbers, not cops. Hijackers loved to prey on poker and craps games because players probably had more pocket money than banks had deposits and were not inclined to report their losses. It was necessary, therefore, to retain the services of freelance gunsels, the most dependable being Jim Clyde Thomas, Tincy Eggleston, and Lois Green. Green was the nastiest, most depraved hit man of his time. He would take the subject for a ride in the country, march him to a pre-dug grave, strip him naked, shoot him in the guts with a double-barreled shotgun, kick him into the hole, cover him with quicklime, and bury him while he was still alive, screaming for mercy.

Another dependable gunsel was Ivy Miller, who bushwhacked a gambler named Sam Murray after he made a move on Benny’s territory in 1938. At the time, the rubbing out of Sam Murray must have seemed like just another shooting, but it touched off a gang war that blazed across Dallas and Fort Worth for the next twenty years. Even after Benny departed for Las Vegas in 1946, he remained a major presence in the Dallas and Fort Worth underworld. Every time a body was discovered in a shallow grave of quicklime near Lake Worth or at the bottom of a vat of coke acid at a steel mill in East Texas, someone was sure to bring up Benny Binion’s name. He always said he had no part in any of the killings, but then Benny would say that, wouldn’t he?

Benny’s longest-running feud was with a gangster name Herbert “the Cat” Noble, so called because a dozen attempts were required to kill him. The feud was like those old Tom and Jerry cartoons, except the bullets and bombs were real.

Noble was the classic nemesis for a man of Binion’s temperament. He was everything Benny wasn’t—suave, debonair, a dashing figure who wildcatted in the oil patch and flew his own small fleet of airplanes. He was something of a ladies’ man too, and fairly well educated, at least by Benny’s standards. Noble was a city boy, raised in West Dallas, which also spawned such infamous outlaws as Clyde Barrow, Bonnie Parker, and Raymond Hamilton. By the late thirties he was a bodyguard for Sam Murray. After Murray was killed, Noble recruited one of Benny’s most valued men, Ray Laudermilk—he was Binion’s “steerman,” the guy who steered clients off the street and up to room 226. The two of them took over Murray’s operation. Noble and Laudermilk set up several lucrative policy wheels and a downtown craps game at a joint called the Airmen’s Club, near the intersection of Pacific and Ervay.

This was a betrayal that could not go unchallenged. Laudermilk knew all of Benny’s regular pistolmen, so he wasn’t suspicious when a skid-row bum named Bob Minyard walked up to his car window, drew a pistol, and shot him dead. Noble accepted his partner’s death as a business omen and promptly shut down his policy wheels. He was able to retain the craps game at the Airmen’s Club, however, when he agreed to give Benny his usual 25 percent cut. As for the skid-row bum, Bob Minyard, he became one of Binion’s regulars after that.

During the boom brought on by World War II, Benny expanded his operation to Fort Worth and bought an interest in Top O’Hill Terrace, the notorious gambling hideaway just west of Arlington. Everyone in the rackets was making big money by this time. The Airmen’s Club was doing so well that in January 1946, Benny decided he deserved 40 percent of the action. Noble refused, in effect challenging Benny’s rule, and a day later the cops closed Noble down. Noble lived in Oak Cliff, but he also had a ranch just north of Grapevine, and as he was driving to the ranch the following night, three men in a car drove up behind him and started shooting. Pretty soon two cars were careening down country roads at speeds of ninety miles an hour, exchanging gunfire. Noble managed to stop and flee on foot, but a slug caught him in the back as he escaped into the woods. Hiding under a farmhouse until help arrived, Noble was able to recognize his assailants: Lois Green, Bob Minyard, and a thug named Little Johnny Grissaffi. A few days later, while Noble was in the hospital recovering, three of his boys bushwhacked Minyard in his back yard.

“With Minyard’s murder Benny was on the spot,” a former Dallas police captain explained later in an interview with the authors of The Green Felt Jungle, a book about Las Vegas. “It was the first time someone had actually defied him and lived. He was losing face with everybody in the rackets.”

The rackets themselves were in trouble. World War II was over, troops were coming home, people dared again talk about the future. Winds of reform blew across the land, not just in Dallas but all over America. Ambitious young veterans, presenting themselves as reform candidates for political office, preached a gospel of growth, prosperity, law and order; red-light districts and gambling houses fell on their onslaught. In the elections of November 1946, Benny’s perennial choice as sheriff of Dallas County, the amiable old duffer Smoot Schmid, lost his job to a 33-year-old ex-GI named Steve Guthrie. The district attorney vacancy was captured by Will Wilson, who beat out another reform candidate, Henry Wade, for the job, then hired Wade as his first assistant. Nobody had to tell Benny Binion the party was over.

A month after the election, Benny packed two suitcases full of money and headed for Las Vegas. Las Vegas was just a wide spot on the map in December 1946—there were only two casinos in town, the El Rancho and the Frontier—but was about to blossom into the gambling capital of the world. That same month, Bugsy Siegel opened his “fabulous” Flamingo Hotel and Casino. As usual, Benny’s timing was perfect.

Benny did not cut his ties with Dallas, however. Though he now lived 1,500 miles away, he continued to control the policy racket, and he got a share from all craps games. Herbert Noble, of course, was a problem still to be resolved. Benny posted a reward of $10,000 for Noble’s scalp, the bumped it to $25,000, and then to $50,000, with a craps game thrown in as added incentive. A lot of gunsels sniffed at that proposition, and a lot of them ended up dead. Noble was no patsy.

In May 1948, as Noble drove through the entrance gate of his ranch home, gunmen riddled the car with bullets. He escaped with a bloody and mangled arm. On Valentine’s Day 1949, Noble discovered dynamite wired to the starter of his car, which was parked near the Airmen’s Club. The following September, another high-speed chase ended when Noble’s car overturned. Miraculously, the Cat limped away with just a few bruises and a leg full of buckshot.

Noble was in Fort Worth negotiating the purchase of an old Air Force training center called Hicks Field when the fifth attempt was made on his life. As fate would have it, he had driven his wife’s car that day. So it was that when 36-year-old Mildred Noble climbed into her husband’s car in front of their Oak Cliff home and stepped on the starter, an explosion blew parts of the car over the treetops. Mildred’s body was found one hundred feet from the twisted, blackened frame, her face crushed and one foot blown off.

After his wife’s death, Noble went a little crazy, spending hours alone staring at a photograph of her flower-bedecked coffin. Rightly or wrongly, he believed that the bomb that killed his wife was planted by Benny Binion’s gang, and revenge became his solitary obsession. On Christmas Eve, less than a month after Mildred Noble’s death, the 31-year-old Lois Green, the depraved gunman who liked to bury his victims alive, walked out of the Sky-Vue Club in West Dallas and was ripped apart by the blast of a shotgun. Everyone assumed that Green was done in by Noble’s number one hitter, a gunsel known as the Groceryman. A day or so after Green was killed, the Groceryman arrived in Las Vegas to assassinate Benny but was captured instead by some of Benny’s gangsters, taken to the desert for rehabilitation, and returned to Dallas—ostensibly with a mission. On New Year’s Eve, exactly a week after Lois Green was cut down, Noble walked out onto his front porch and into the beam of a spotlight and the hail of automatic rifle fire.

Again the Cat escaped with his life, but his odds were diminishing fast. As he recovered at Methodist Hospital, a bullet shattered the window glass of his fourth-floor room and lodged into the ceiling. After his release from the hospital, Noble moved from his house in Oak Cliff and moved to the ranch, where a floodlit yard and six vicious dogs offered some security. Attempt number eight came in June 1950, when an assailant hiding in a duck blind opened fire with a machine gun. This time Noble was saved by the armored plating of his bulletproof car.

Paradoxically, during all the bloodletting, there was no organized crime in Texas, not in the sense of the Mafia or a Capone-style operation. Our gangs were strictly homegrown. But Benny Binion was now part of the Las Vegas establishment, which meant that his feud with Noble—and particularly the publicity generated by the brutal murder of Mildred Noble—put a lot of heat on national crime organizations. New York crime boss Frank Costello reportedly canceled plans to move into oil-rich South Texas. By 1951 the Kefauver Senate Crime Committee was holding hearings in Los Angeles, and Benny was on the committee’s list of witnesses “wanted but not (yet) found.” Meanwhile, back in Dallas, Benny had been charged with operating a policy wheel and income tax evasion and was fighting extradition.

In an effort to negotiate a peace treaty between Binion and Noble, Flamingo Hotel president Dave Berman, a front man for the Eastern syndicate, sent a scumball named Harold Shimley to Dallas for a secret rendezvous with Noble. Meeting at a tourist court near Love Field (and speaking into a hidden microphone planted by the Dallas police) Shimley assured the Cat that no one was more grief-stricken by his wife’s death than Benny Binion, that Benny had sworn on the lives of his own wife and five children that he had nothing to do with the bombing.

Noble didn’t buy Shimley’s story. If anything the meeting only escalated the violence. In February 1951, Noble attacked an associate of the late Lois Green outside a West Dallas grocery store and got his earlobe bitten off. Five days later somebody threw a bomb through the front door of the Airmen’s Club. The Cat was away that night. Two months after that, a nitro bomb exploded in the engine of one of Noble’s airplanes, but he was saved by a steel-plated instrument panel. A few days later Noble found another bomb in another airplane. Like all the previous attempts, number eleven failed; but the Cat must have known he was living on borrowed time.

Hell, the attempts themselves were killing him. Once thickset and muscular, Noble had lost at least fifty pounds and looked like a piece of overcooked bacon. His silver-blond hair, once thick and wavy, was now limp and snow white. Though he was only 42, Noble could have passed for 60. He slept—or at least he tried to sleep—with a shotgun next to his bed and carried a carbine everywhere he went. His mind was slipping too, and he had started drinking heavily and taking pills.

And yet in the Cat’s grief-twisted brain a fantastic plot was fomenting. He was planning an air raid on Benny’s home in Las Vegas—kill ’em all, Benny, his wife, his five kids, his dog, his cat. Noble had bought a stagger-wing Beechcraft with extra wing tanks, a bomb rack, and two large bombs, one an incendiary and the other a high-explosive. He even had an airmen’s map of Las Vegas, pinpointing the Binion home on Bonanza Road. Noble might have pulled it off except that Dallas police lieutenant George Butler, who was on temporary assignment to the Kefauver committee, happened to drive up to the ranch just as Noble was doing his final checkout. Noble made a grab for his carbine, but Butler beat him to the draw. At that point Noble crumpled to the ground, blubbering like a baby and sobbing that Benny got all the breaks, that nobody gave a damn what happened to poor Herbert Noble.

That wasn’t entirely true. Someone still cared. On a hot August day in 1951 a land bomb, planted two feet from the mailbox and directly under the spot where a driver stopping to pick up his mail would sit, blew Herbert Noble into an almost infinite number of pieces. Nobody ever found or even looked very hard for his killer—though gangland rumor had it that the shock waves of the explosion knocked Jim Clyde Thomas, one of the premier hitters of the time, out of a nearby tree and broke his arm. Dallas County sheriff Bill Decker, the longtime deputy who had replaced the hapless Steve Guthrie in 1950, summed up his official take on Herbert the Cat this way: “He was folks. He lived here, and it takes all kinds of people to make a city.”

The good ol’ boy network that Benny Binion helped create in Las Vegas—a cabal of entrepreneurs, lawyers, cops, prosecutors, judges, and politicians—was nearly impregnable. But in the end it was no match for the tenacity of Dallas’ post-war crusaders or their lust for vengeance.

Vegas was Benny’s kind of town, businesslike and practical, the way Dallas had been in the thirties, only more direct, less hypocritical. The business of Vegas was gambling, which meant that everyone could be more out-front. Semantic distinctions concerning loans, gifts, and contributions were not the sort of thing that got people confused or caused them to lose sleep. When Benny loaned $30,000 to Clark County sheriff Ralph Lamb, for example, he didn’t expect Lamb to repay the money, but he expected Lamb to be there for him when he needed a favor. And Lamb was, just as Benny was there for Lamb when the sheriff was tried for bribery in 1977. Testimony appeared to establish beyond a doubt that Lamb had taken bribes. Nevertheless, U.S. district judge Roger Foley, Sr., whose son Thomas was one of Benny’s lawyers, dismissed the case. Thomas Foley and his brother Roger Foley, Jr., eventually became judges themselves, as did Benny’s other chief lawyer, Harry Claiborne.

The network was a living thing, as solid as gold. In 1951, even while Benny was fighting extradition to Texas, the governor of Nevada and the Nevada Tax Commission saw no reason to deny the Cowboy a license to operate his new casino, Binion’s Horseshoe. State senator E. L. Nores, who appeared before the commission as a character witness for Binion, claimed that Benny’s only limitation was his unbounded generosity. It was a subject on which the senator was well qualified to speak, Benny having gifted him with a new Hudson Hornet automobile a short time before.

Back in Dallas, Henry Wade had moved into the district attorney’s office when Will Wilson was elected to the state supreme court, and was plotting a strategy to get Benny behind bars. Work through the federal courts, Wade reasoned, nail Binion on charges of income tax evasion, then hit him with gambling charges after the feds had returned him to Texas. Wade had plenty of evidence, which he shared with the feds. Documents and records seized from the Harlem Queen policy headquarters on Texas Highway 183—and from Benny’s safe-deposit box at the Hillcrest State Bank—showed that in 1948 Binion had netted more than $1 million from the rackets in Dallas, hardly any of it reported to the Internal Revenue Service. Juries found Binion and his partner Harry Urban guilty of tax evasion. But while the judge in Dallas sent Urban to prison, Binion’s case was transferred to Nevada jurisdiction, and he got off with probation and a small fine.

Outraged by the light sentence, Wade traveled to Washington, where he consulted with U.S. attorney general James McGrannery and other high officials of the Truman administration. According to one report, orders to get Benny Binion were issued the following summer from the Democratic National Convention. McGrannery sent two attorneys from the Department of Justice to Dallas to supervise a new grand jury, and the FBI and the IRS made the investigation a priority. Wade was so determined to get Binion that he had an assistant DA furnish the FBI with an extensive dossier outlining Benny’s criminal history, real and alleged. The FBI showed the dossier to a federal judge, who, as Wade recalls, read it and was incited to remark, “I’m gonna get that S.O.B. back to Texas.”

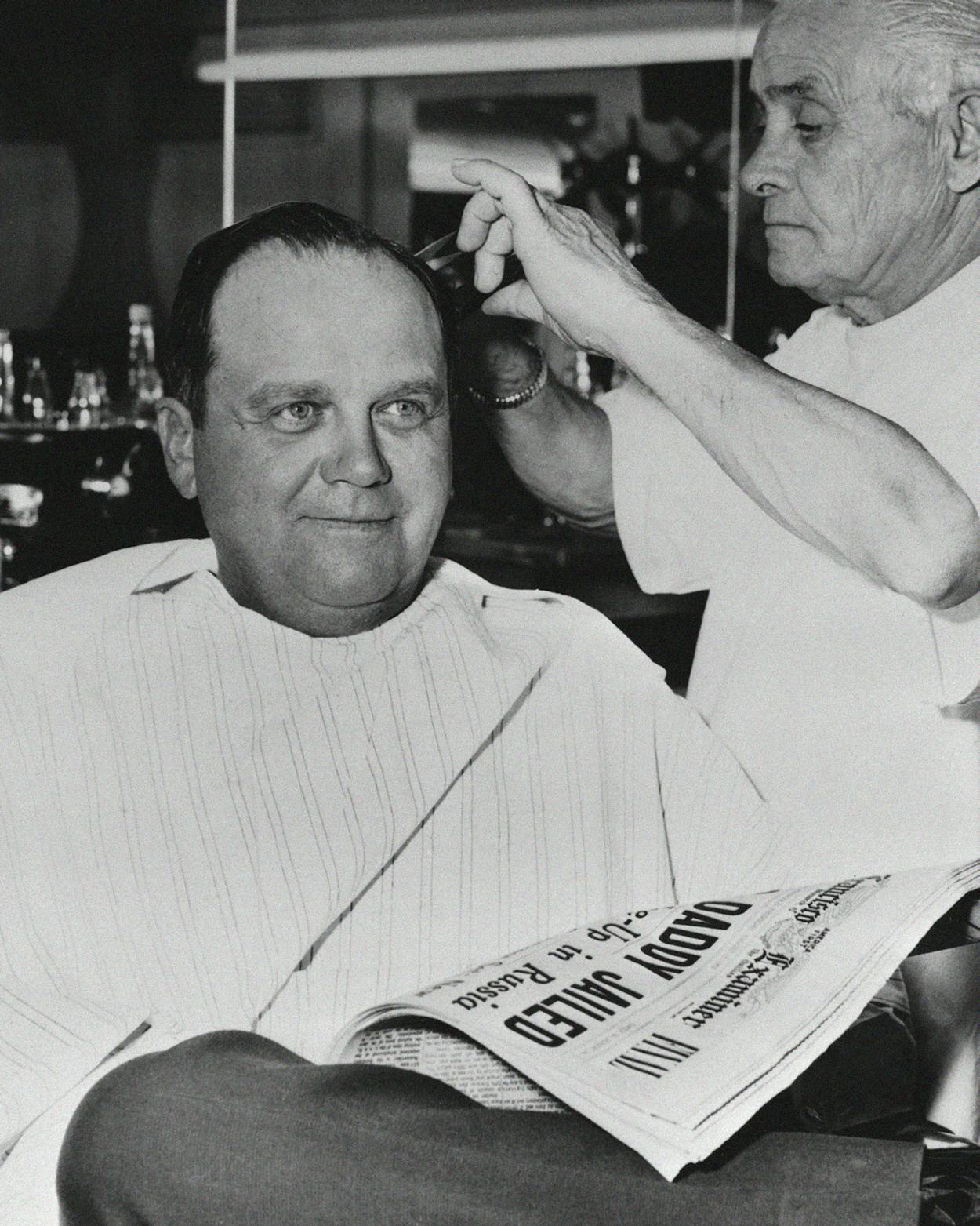

In June 1953 Benny had his chauffeur, a large black man who went by the name of Gold Dollar, drive him from Las Vegas to Dallas, where he surrendered to his old friend Bill Decker. The following December, he pleaded guilty to federal charges of income tax evasion and state charges of operating an illegal policy wheel. By previous agreement, the sentences would run concurrently: five years in the federal prison at Leavenworth, a fine of $20,000, and a payment of $776,000 in back taxes, penalties, and interest.

Benny paid his $20,000 fine on the spot, peeling the bills from a much larger roll he had brought along to bribe the judge. Benny apparently was under the misapprehension that U.S. district judge Ben Rice was prepared to give him probation in exchange for a gift of $100,000. “The FBI threatened him and scared him off,” Benny claimed later. Binion did 42 months of hard time and was released in October 1957. Wade warned him to stay out of Texas or face additional prison time, but a few months later the Cowboy was riding in the Fat Stock Show parade in downtown Fort Worth, as sassy as ever.

Never again would Benny Binion be allowed to hold a gambling license in Nevada, not that it really mattered. His wife, Teddy Jane, and his eldest son, Jack, were much better able to handle the daily affairs of the casino and hotel business. Teddy Jane was a good, hard-headed woman, not easily influenced by the gamblers and gangsters who took advantage of Benny’s generous nature. As a young woman she had predicted, “If I marry Benny Binion, I’ll spend my life in a room above a two-bit crap game.” She was half right. She spent her life in a room above Binion’s Horseshoe. Teddy Jane ran the casino as though it were a mom-and-pop cafe, trusting no one but herself to make bank deposits. She was a familiar sight on Fremont Avenue, this scrawny old lady with dyed hair and a cigarette between her nicotine-stained fingers, trudging from the casino to the bank with hundreds of thousands of dollars stuffed in the pockets of her trench coat.

Prison took something out of Benny and maybe put something else in its place. He got religion in Leavenworth from a Catholic priest. “Religion is too strong a mystery to doubt,” he said. Benny was 52 when he got out. His face was gentler and rounder, his blue eyes cloudy and not so hard, his waist and hips going to fat, his voice husky but good-humored. He still loved to talk—God how he loved to talk!—and he held court every afternoon at a corner booth at the Horseshoe, telling old war stories. Hell, yes, he remembered gunning down Ben Frieden in ’36. There had always been a dispute over how many bullets were fired from Benny’s .45. Was it one, as Benny maintained at the time, or three, as Bill Decker told the grand jury? “Weren’t no mystery to it, don’t you see,” Benny would cackle. “I shot once and hit him three times right in the heart.”

And yet there was no question that the Cowboy had mellowed. When a preacher from North Carolina lost $1,000 of his congregation’s money shooting craps at the Horseshoe, Benny gave the money back. “God may forgive you, preacher,” he said, “but your congregation won’t.” Life was a crapshoot, that’s what made it exciting. In 1980 a high roller from Austin walked into the Horseshoe with two suitcases, one full and one empty. He took $777,000 from the full suitcase and slapped it on the “don’t pass” line. Benny nodded: Damn right he’d fade the bet. Three rolls later the man walked out, this time with both suitcases full. Life in the fast lane wasn’t all that different from life anywhere else, was it? Nobody got out alive. Benny’s eldest child, Barbara Binion Fechser, was a drug addict and died from an overdose in 1983, an apparent suicide; and his youngest son, Ted Binion, pleaded guilty to a drug charge in 1987.

The stigma of being a convicted felon made Benny uncomfortable, and obtaining a presidential pardon became his final obsession. He almost got it in 1978 when his friend Robert Strauss, then the chairman of the Democratic National Committee, brought Benny’s plight to the attention of the Carter administration. By now his application for pardon had been denied four times, but Benny proposed a deal. He claimed he could deliver a vote in the U.S. Senate on the Panama Canal treaties in return for three presidential favors. One was a federal judgeship for Benny’s friend and lawyer Harry Claiborne, the second was an exemption from interstate trucking regulations for a business acquaintance in Oklahoma, and the third was a pardon for himself.

It might have come off too, except Benny couldn’t keep his famous mouth shut. The Senate ratified the treaties; Benny never made public which vote he delivered. Claiborne got his judgeship and was later impeached for income tax evasion. Trucking regulations became irrelevant when Benny’s friend went broke. And just as the Justice Department was ready to move on his application for pardon, word of a Binion wisecrack reached Washington. Mafia hitman Jimmy “the Weasel” Fratianno had testified that Benny had hired him to kill a gambler named Russian Louie Strauss, which the FBI knew was not true. But rather than issue a simple denial, Benny replied that, “Tell them FBIs that . . . I’m able to do my own killing without that sorry son of a bitch!” So much for pardon application number five.

During Ronald Reagan’s first term, Nevada senator Paul Laxalt suggested to Benny that a contribution to Reagan’s campaign treasury might help. Benny sent $15,000, and two days later his pardon was denied. In the old days such a perceived betrayal might have tempted the Cowboy to call Lois Green. But a mellower, more mature Benny was content to buy a newspaper ad calling Laxalt a welsher. Benny said that he intended to live long enough to piss on Reagan’s grave, but he finally crapped out.

What made Binion’s Horseshoe such a success—at least in Benny’s opinion—was adherence to two bedrock rules. First, the casino catered to hard-eyed, no-nonsense gamblers. No limits, no entertainment, no gurgling fountains or fancy decor. Until recently, the dealers wore jeans. The specialty of the house was (and still is) generous drinks and Benny’s greasy, fiery chili, made not from Chill Will’s recipe as advertised, but from Smoot Schmid’s old Dallas jailhouse recipe. Second was Benny’s promise that cheaters and thieves would be escorted to the alley, where their arms and legs would be broken by security guards highly qualified for the assignment. Frank Sutton, a detective sergeant with the Las Vegas metropolitan police department, says, “The Horseshoe was the only casino in town that didn’t believe in calling the police. They took care of trouble their own way.”

The wild West motif worked in Las Vegas for many years, just as it had in Dallas, but again times were changing. By the mid-eighties, Las Vegas was trying to recast its image as a sort of adult Disneyland, and the Horseshoe’s vigilante tactics were an embarrassment. After the Cowboy suffered two major heart attacks and surrendered even a pretense of control, the rough stuff got out of hand. A casino employee chased down a drunk who had thrown a brick through a window, calmly shot him to death on a street a few blocks from the police station, then strolled back to the Horseshoe as though nothing had happened. Two men assumed to be cheating at blackjack were hauled into the security office, beaten, and robbed.

In January 1988, Benny’s grandson, 33-year-old Steve Binion Fechser, and two security guards were convicted of assaulting the two blackjack players. But instead of passing sentence, district judge Thomas Foley took it on himself to overturn the jury verdict, an action within the power of a Nevada judge.

That didn’t end it, however. In April 1990, Fescher, his uncle Ted Binion, and six guards were indicted on federal charges of conspiring to kidnap, beat, and rob customers of the Horseshoe—particularly blacks and other people considered undesirable by the Binions. The case will be tried starting October 8 in the court of U.S. district judge Philip M. Pro.

Teddy Jane Binion will no doubt be among the spectators, as she was at her grandson’s trial three years ago. During a break in the trial, she approached chief deputy attorney general John Redlein, who was prosecuting the case.

“Haven’t I seen you in the hotel?” she asked.

“I used to have lunch over at the Horseshoe fairly often,” he replied, “but I guess I won’t be welcome after this, heh?”

“Not at all, honey,” she told him. “This is just business.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Longreads

- Crime

- Gary Cartwright

- Dallas