This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

My brothers at the Zeta Beta Tau fraternity at the University of Texas did not typically spend their summers in Austin. Some interned at prestigious law firms in Houston or hospitals in Dallas; others were floor runners on the Chicago commodities exchange. Many finagled trips abroad from their parents. But in the late summer of 1993, Joshua Alan Levine wasn’t interested in such pursuits. The philosophy major and honor student had a problem: He had thousands of dollars of debts—many of them from gambling—but he didn’t have the cash to pay them off. He found himself near the Drag, heading for the First State Bank. Wearing blue jeans and a Chicago Bulls cap that covered his sandy brown curls, he looked like any frat rat ready to make a withdrawal. Only this transaction would be made not with a pen but with a gun.

Josh had been casing the bank for a month. He would go there as often as three times a day, each time asking for his balance. Then he would ask to use a phone and—pretending to make a call—observe the bank in action. The tellers knew Josh on sight. One had even memorized the name of the person to whom he regularly sent large money orders. What the teller didn’t know was that the person was a Houston-area bookie and that several months earlier he had threatened to castrate Josh if he didn’t pay up. Josh had lost $11,000 to the bookie during that year’s National Football League playoffs.

Many UT fraternities have become clubs for the sons of millionaires; belonging to one is in many ways a game of survival of the richest. Throughout his four years at UT, Josh always had to struggle to afford the Zeta Beta Tau (ZBT) lifestyle. But his financial circumstances were of little importance to his fraternity brothers. I knew many students at UT with serious personal problems, but I’d never have figured Josh as a candidate for collapse. I pledged ZBT in the fall of 1988, a year ahead of Josh. We were more than casual acquaintances—he was the “little brother” of one of my pledge brothers, and we shared bong hits and pickup basketball games. Josh had every reason to be successful: He worked two jobs to help pay his tuition and ZBT’s $1,350-per-semester tab. After his first semester, his grade-point average never fell below 3.0. He was exceedingly handsome and fit—the kind of guy who never lost his tan. Josh was an aspiring writer, and he could talk about deep philosophical questions with ease. He had been president of ZBT and was a member of UT’s elite Silver Spurs, the service organization that watches over UT’s Longhorn mascot, Bevo, at home football games.

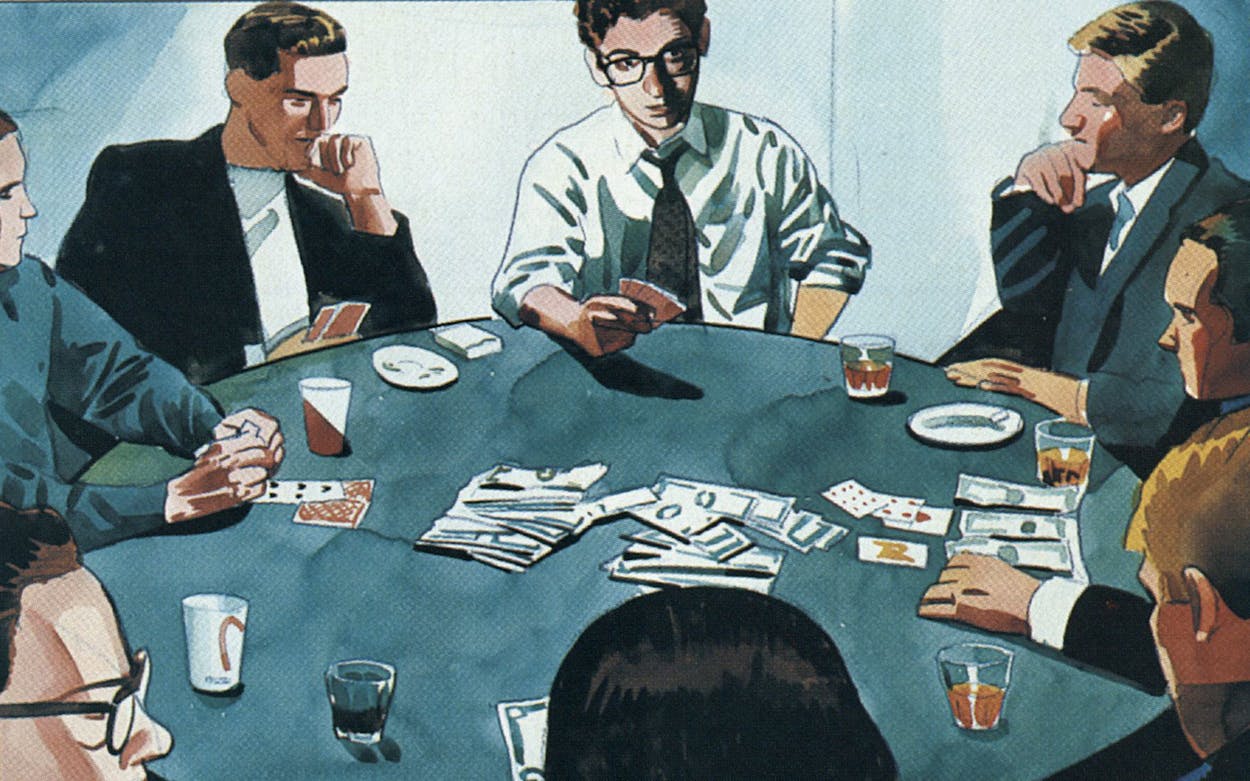

Along with the drinking, drugging, and partying that have been facts of frat life for decades, now there is widespread gambling. When Josh was a member of ZBT, the stiffest competition at the fraternity house, with the exception of the basketball court, was at the card table. Before dinner every night there was a poker game, with eight to twelve regulars playing at a round table in a dimly lit corner of the dining room. It was a tight crowd, not very friendly to strangers. Complicated wild-card games were the norm. Most players usually won or lost $50 in an afternoon, though it was not unheard of for someone to win $250. A pledge brother of mine who now works in Los Angeles quit his job waiting tables at a pizza joint because he was winning so much. No one really got into the hole too deep, except for one brother who had constant problems accessing his trust fund.

Poker and blackjack aren’t the only forms of gambling in the UT fraternity system. The most prevalent form of illegal gambling is sports betting. “I don’t think it’s ever been a problem for a UT frat student to find someone who’ll take a bet,” explains Austin Police Department (APD) vice officer William H. Horn, who handles most of the city’s gambling cases. For rich kids, who do most of the betting, there’s little risk: They can always get their parents to cut them another check. After the Austin police busted a $600,000 bookmaking ring, one fraternity man told Horn that he planned to pay off a $12,000 debt by “cashing in some stock.” Fraternity gambling is so ubiquitous that the cops tend to look the other way—or use the kids to get to bigger bookies. Of course, the police can’t look the other way when a compulsive gambler turns to bank robbery.

In his journal entry for July 25, 1993, Josh wrote: “I am seriously considering robbing a bank. Is it possible?” The solution had come to him on one of those lazy summer afternoons when he had nothing better to do than smoke some pot, ingest some psychedelic mushrooms, and dangle his feet in the swimming pool of the apartment complex he lived in. “What day is a good day?” he wrote. “What time?”

On August 17, the time had come. As Josh turned down the alley behind the bank, he felt euphoric, just as he had the summer before, when he had won $25,000 betting on baseball. It was 9:47 a.m. The bank’s morning rush was over, and as Josh knew, the security officer was taking his scheduled five-minute break. Josh unzipped a black book bag and pulled out a pair of rose-tinted goggles, black neoprene driving gloves, and a camouflage hunting mask. He hesitated—wondering for a moment if he would be able to live with himself afterward. Then he pulled out a 9mm semiautomatic Astra and stormed the bank.

“This is a f—ing robbery!” he screamed, pointing the gun at two tellers. “Put the money in the bag! In the f—ing bag!” One terrified teller tried to hand him the money. “Not to me,” Josh yelled, gesturing with the blue-steel Astra. “In my f—ing bag!”

Then Joshua Alan Levine ran away from the First State Bank with $12,097. He didn’t know whether he would be able to live with himself, but for now, at least, he knew he would be able to live.

“Every night of the week, you could find a game to bet on,” Josh said. “When I was broke, I could make money for dinner and lunch. It’s real easy to win only twenty dollars. Real easy. I was totally in the mania.” Josh and I were sitting in the Twin Sisters cafe, a casual lunch spot in San Antonio’s Alamo Heights neighborhood, last July, nearly a year after he had robbed the bank. Josh offered an easy smile as he reminisced about the gambling habit he had picked up from his ZBT brothers. In his striped blue shirt and khaki shorts, he still looked like a Zebe, not a criminal out on bail and awaiting sentencing. Beside his barely touched bowl of gazpacho sat the latest issue of the Paris Review. It was difficult to believe that just a week before, my friend had been convicted in U.S. district judge Sam Sparks’s court on two felony counts: bank robbery and the use of a firearm in a crime of violence.

After the tellers had stuffed the money into his black bag, Josh ran out of the bank, but he forgot to zip up the bag. More than half of the $12,097—in packets of tens, twenties, and fifties—fell on the ground just inside the bank’s back door. He kept running. Not a hundred yards farther, he slammed into a man loading a U-Haul truck. Even more money went flying. Josh made it to his car, which was parked a couple of blocks away, and drove to his apartment. He changed out of his robber’s gear, made a few phone calls, and brushed his teeth. His plan was to drive to his grandparents’ home in Memphis, Tennessee.

He never made it to the city limits. The two tellers had slipped packets of “tracer money” into his bag. Tracer money emits radio waves, and the APD’s robbery detail has four vehicles equipped with a device that can track them. Officer Rolando G. Fuertes homed in on Josh’s car near Interstate 35 and the UT campus and caught up with Josh when he stopped outside a Planet K off the Rundberg Lane exit. The police recovered the camouflage mask, the neoprene gloves, and the Astra under a white quilt in the trunk of his red 1991 Toyota Corolla. They found his journal, complete with a diagram of the robbery, in a backpack on his front passenger seat. And they recovered all but $4 of the stolen money.

In interviews with the police and FBI agents after his arrest, Josh said he wouldn’t be able to afford his own lawyer and repeatedly asked when the court would assign him one. “Son,” said FBI special agent James Echols, “this is what we call an open-and-shut case.” To save time and money, the government offered to plea-bargain: a four-year prison sentence in return for a guilty plea. After all, he had been caught red-handed. But Josh refused the government’s deal. He was still gambling. With financial support from family and friends, the Levines hired Jack Zimmermann, a high-profile defense attorney from Houston, to defend Josh. Zimmermann believed he could best defend Josh with a plea of not guilty due to insanity, and he urged Josh to risk a possible seven-to-ten-year prison sentence. Zimmermann would base his defense on Josh’s mental state at the time of the robbery. Psychologists said Josh suffered from bipolar disorder, sometimes called manic depressive illness, a condition that was diagnosed after the robbery. It was a long shot.

In court Zimmermann portrayed Josh as an unstable young writer who didn’t believe he could describe a bank robbery until he had committed one. Zimmermann told the jury that Josh had turned himself into the protagonist of his future novel—a “pretentious yet wonderful” character named Reynaldo Zak, who was, in fact, a character in Josh’s fiction writing. The jurors were unsympathetic. They saw Josh not as a disturbed young talent but as a spoiled frat boy.

Josh Levine was born on July 19, 1971, in Memphis. When he was five his parents moved to a middle-class neighborhood in San Antonio. His father, Michael, had a master’s degree in education with a specialty in counseling from Memphis State University but would later switch to retail sales, becoming part-owner of two Polo shops. Josh’s mother, Nancy, is a longtime public-school administrator.

“I was considered rich, upper class,” Josh told me at Twin Sisters. “I was wearing the best clothes money could buy. It was an image thing. It confused me a lot.” In the public high schools during the mid-eighties, a preppy wardrobe established one’s social standing. At MacArthur High School, Josh blended perfectly with the popular, rich crowd. As a senior he was voted vice president of the student council. He was an A and B student, just below the top 10 percent of his senior class. He belonged to the honor society and the creative-writing club and was active in Jewish youth groups.

While Josh was in high school, the Levine family fell on hard times. In 1986 his father’s faltering Polo shop was bought out. Michael then opened a women’s clothing store, but in 1989—the year Josh went to UT—it went out of business. During his senior year in high school Josh worked evenings, often well past midnight, as a line cook at the Alamo Cafe. After graduation he also worked as a lifeguard. His academic record and financial need helped him win a scholarship and qualified him for financial aid—together worth more than $11,000 over two years.

But Josh was hooked on an upper-class lifestyle. When the kids he hung out with headed for UT, they shunned the on-campus dormitory, Jester, in favor of the private, off-campus dorms—Dobie, the Castilian, and Contessa West—which were almost twice as expensive. Josh and his parents agreed that rooming at Dobie was imperative: It was smaller and more personal than the massive Jester. It was also where all the Jewish women were, and they thought it was important that he be surrounded by his own kind. When it came to fraternities, though, it was harder to convince Nancy Levine that the social advantages outweighed the additional expense.

But ZBT, then the most prestigious Jewish fraternity on campus, was rushing Josh. And for someone as plugged in to the Jewish social scene as Josh was, ZBT was a necessity. Boasting more than 160 members, it was the largest of UT’s three Jewish frats. It was also the wealthiest: Two members’ fathers owned companies on the Nasdaq. The frat was dubbed Zillions, Billions, and Trillions. ZBT threw parties and mingled with UT’s biggest and richest fraternities: Sig Ep, Delta Tau Delta, Fiji, and Kappa Alpha. (In November 1993 ZBT’s national organization revoked the UT chapter’s charter because of a violation of its “no pledging” policy. Despite several warnings, ZBT had continued to treat its new members as pledges. But in January 1994 ZBT reopened as Pi Lambda Phi.)

In 1989 Josh joined the frat with typical pre-freshman logic—UT was a big school, and to make it at a big school one had to be a part of something. And ZBT wanted Josh. He was articulate and muscular, a natural leader. He could brag about his hometown Spurs or how much he enjoyed the writing of Jorge Luis Borges. He could hold his liquor, and he was good with the girls—in ZBT lingo, he cut butt. The fraternity went out of its way to make itself affordable for guys like Josh. As a freshman, Josh waited tables at the ZBT house during dinner and was the house’s lunchtime busboy. During my three years in ZBT, I too was a waiter. Josh and I quickly became close. Our paths had been so similar: We were in the small minority of liberal arts majors. While our pledge brothers discussed their stock options, Josh and I talked about the books we had read recently. Neither of us had a family business to fall back on after graduation, a fact that bothered Josh more than me. Josh was more real to me than the other Zebes were; we shared our doubts and concerns. But I never knew about his gambling.

I was awestruck by what Josh put himself through just to be a Zebe. While his fellow freshman pledge brothers spent as little time as possible at the ZBT house, Josh worked there all day, absorbing nonstop abuse. If the pledge trainers feared that a pledge had spit in their dinner, as was often the case, they would holler for the pledge and order him to take a bite. Then they would throw their food at him. Josh was elected rush captain his sophomore year and—on the promise that he would get new pool cues—president his junior year. “He was the guy who everyone respected,” says Elliott Finebloom, one of Josh’s pledge brothers. “He was the man.” He had a serious girlfriend, a redheaded Jewish beauty from California. Josh also worked outside the fraternity. In his four years at UT he waited tables at the Cadillac Bar, shoveled manure at an equestrian center, and was a salesman for a software company and a page at the state capitol.

By outward appearances, Josh seemed to be in control of his life. But he could never shake the feeling that he didn’t belong—that because his parents could afford to send him only $850 a month to cover his living expenses, he was inferior to his pledge brothers. While they went on about how they couldn’t get full access to their trust funds until they were 25, Josh dreamed of being a writer. He told his frat brothers that though life would be rough for a few years, someday he would be an established Hollywood screenwriter. “I wanted to be known as the guy who was the Silver Spur,” he told me, “but who was also like Michener.” But Levine’s writings were anything but Michener. His prose was dark and intense, more personal than narrative. “Waking to the sound of running water and far matriculations,” reads one of his novellas, “the beamy sun prodded my eyes. . . . The wondrous light rushed me into its searing touch, a nuance of heat that made me secure. Secure to lay beneath it, finally thinking of something else other than her.”

In his drive to be accepted, Josh became addicted to some ZBT vices. His problems started with the clique he hung out with. “Team Dobie” consisted of about ten guys, all of whom smoked marijuana at least once a day and—except for Josh—were rich. “I was smoking so much,” Josh told me, “that even when I wasn’t smoking I was still high.” While Josh and a frat brother were driving back to Austin from a spring break in California, a policeman pulled them over just outside of Palm Springs. Levine, in the passenger seat, was too stoned to realize why the car had stopped. When the officer asked for a driver’s license and insurance, he noticed Levine, reading the liner notes to a compact disc, with a joint still burning in his mouth, but he was not charged.

Many ZBTs were heavy gamblers, and to maintain respect among his clique, Josh made his first football wagers in the fall of 1990, his sophomore year. He started small, with a few $25 bets. Soon he was betting on up to nine games a weekend, often risking more than $200 a game. Although Josh told me he was “unbelievably successful” from the start, he was asking his pledge brothers for loans as early as that first semester of his sophomore year. On several occasions one of his roommates, a friend from elementary school, loaned him $100.

In the beginning Josh was very businesslike when he needed money and was punctual with repayment. But as his gambling grew more serious, so did his debts. “Most of the big gamblers in the house were rich kids,” explained Josh Hanft, who was treasurer of ZBT when Josh was president. “They could afford to lose the money. But Levine didn’t have money to pay. It would hurt Levine more. He would bet way too much money trying to get back to even.” Hanft loaned Josh $1,000, which Hanft said he paid back on time.

Every UT fraternity had a bookie. Most were strictly small time, refusing to accept bets of more than $300. They never offered official Vegas odds; instead they tweaked the betting lines in their favor. Fraternity bookies also had a bad habit of not paying out winnings on time, if at all. They operated on a credit system in which bettors were free to wager their way out of debt. Since no frat bookmaker would violate the spirit of brotherhood and threaten a fellow fraternity man with bodily harm, there was no effective method of debt collection.

By the spring of his sophomore year, Josh had tired of the fraternity bookmakers. He wanted the thousand-dollar action and better odds. A fraternity brother who was regarded as the biggest gambler in ZBT hooked Josh up with a new bookie, a former ZBT who had become a professional bookmaker. Almost immediately, Josh fell into large debt to the bookie. “I didn’t have the money,” Josh recalled at the cafe. “I told him I’d pay when I could. It set a bad precedent.”

In spring 1992, the second semester of his junior year, Josh was elected president of the fraternity and inducted into the Silver Spurs. By then, Josh had paid back the bookie and persuaded him to take his bets again. But after Josh had a hot couple of weeks, the bookie took his revenge and refused to pay Josh his winnings. And there was nothing Josh could do about it, except get a new bookie. So several Zebes put him in touch with another big-time bookie, this one based in Houston.

During the summer of 1992, gambling became more for Josh than a way of getting enough money to keep up with the fraternity’s millionaires. It became a compulsion, an all-consuming emotional commitment. So much so that Josh made the gambler’s fatal error: He began to look for a way to beat the system. Employing his background in philosophy, Josh came up with an approach that he believed weighted the odds in his favor. “My thing was that you separate the money from the emotions and desire,” he told me. “You make everything completely sober. It’s like the powers of chance, the powers of the universe. I tried to do everything in my power to even those out.” His idea was to find someone who wasn’t a gambler to make his picks, because Josh believed that that person would not be affected by winning or losing.

He found a fraternity brother who was a self-proclaimed baseball expert with a knack for picking winners. That summer, Josh’s friend would phone him every morning and rattle off four or five picks of the day; Josh would decide how much money to bet on each game and call his Houston bookie. The only condition was that Josh was never, ever to bet on the Texas Rangers, his friend’s favorite team. The friend rarely picked overwhelming favorites; instead, he stuck by the streak theory: Bet on teams on two- and three-game winning streaks, but never on a team that has won more than four. Somehow, it worked. “Every night was super huge,” said a smiling Josh. “I was winning nine hundred dollars a night. We couldn’t believe it. Every week we’d go eight and one. It was beautiful. ”

In exchange for his picks, Josh said, he paid his expert 15 percent of the profits—as much as $150 a week. The only rule Josh imposed on his friend was that he could never bet on the same games he gave Josh. That was a karmic violation of Josh’s philosophy, the dreaded mixture of emotions and money. But the friend couldn’t help himself. Josh said his friend eventually wanted to get in on the action too. He picked a bad night to cross Josh’s only rule: Josh lost big, the friend more modestly. The system was ruined, and Josh turned to other frat brothers for picks.

Josh said he won $25,000 that summer. He had finally achieved the financial level of his fraternity brothers. He didn’t have to work a real job. He played the stock market. He could afford to buy his girlfriend presents and take his friends out for dinner and buy thick bags of skunky-smelling pot. He and a roommate went on a shopping spree. They bought a big-screen television, a beveled-glass coffee table, and a leather couch. They spent $8,500. “It was,” Josh recalled wistfully, “a great summer.”

Word of Josh’s amazing season quickly spread through ZBT. A sophomore fraternity brother started hanging out with him. After watching Josh’s ludicrous system, the sophomore decided to become a bookmaker. “He thought it would be so easy,” Josh told me at lunch last July. “He started saying, ‘I gotta book. I gotta book.’”

It took Josh and the ZBTs only two weeks to put the rookie bookie out of business. “Well, he was not very smart,” said Josh. “A bookie needs to have some savvy.” For example, he said, when the underdog Chicago Cubs jumped out to a 3–0 lead against the St. Louis Cardinals in one afternoon game, he phoned the upstart bookie and placed $300 on the Cubs. Unaware that the game had already started, he took the bet.

“He never turned down a bet—it was candy from a baby, ” added another ZBT. “Everyone was winning money off the dude.” After the frat bookie was unable to pay more than a thousand dollars in losses, he abandoned his bookmaking dream for the summer.

Josh was living a gambler’s lifestyle. Gone was any vestige of his hard-work ethic. He was more interested in turning a quick buck. Still under the influence of his summer of luck, Josh concocted a scheme: If a frat brother gave him some investment capital, he would guarantee that after one month he’d return the entire amount, plus 50 percent interest. His plan was to bet half of the investment on his pick of the week. A friend of Josh’s couldn’t believe he was serious. Why would he guarantee so high a return when plenty of ZBTs would jump at a mere 10 percent yield?

“He honestly didn’t think they would lose,” said the friend, who eventually talked Josh out of the plan. “It blinded him that this was someone else’s money he could lose. It just blinded him.”

Just before his senior year, Josh moved into a house with seven other Zebes. Thanks to his winning streak, Josh had plenty of cash on hand. Partly because his roommates were lazy but mostly because he wanted to impress them, Josh paid the bills out of his own pocket. He was not always reimbursed.

Josh’s gambling addiction impaired his judgment as ZBT president. In what was probably his most popular decree, he reinstated blackjack night, which had been discontinued in 1988, during my freshman year. His reasoning: “The frat needed the money. ” Blackjack night was usually held on Sunday in the house’s library. Josh found three friends who were willing backers, and each night the bank was at least $3,500. The tables were run on Colorado rules—only $5 or $10 bets allowed. The house provided a keg of beer and raked a percentage off the tables each hour. Players from any fraternity could attend, as long as they knew a Zebe.

The blackjack scheme didn’t yield much in the way of profits. “The dealers were always too stoned, and they made mistakes,” Josh explained. “It was too lax. People were drinking beer, joking. It was more of a social atmosphere.” About blackjack night, Josh told me: “I’m not saying that as a good president I should have done that, but as a president with a gambling problem, that’s what happened.”

In the fall of 1992, the extent and complexity of gambling in the UT frat system seemed to have reached epidemic proportions. A loose group of six ZBT bookmakers had centralized their operations. Their system was simple. They set up a phone number in Austin, which bettors called to hear the latest lines and place bets. The maximum bet was $300, except for the “frat daddies,” as the especially wealthy bettors were known. By the NFL playoffs, the bookies were sitting on a $600,000 operation. But in late November 1992, the APD vice squad received an anonymous call from a Zebe in serious debt who had decided to rat on his frat-brother bookies rather than pay up.

Late in the afternoon of January 20, 1993, as a burgers-and-beer party raged at the ZBT house and the daily pickup basketball games were in full swing, the APD vice squad raided the apartments of the ZBT bookies. One complex overlooked the frat house. When the vice cops stormed the apartment, with one officer breaking a window and another knocking down the door, the incident was in full view of the basketball court. “We were in awe,” remembers Josh Hanft, who was playing ball at the time.

By the fall of 1992, Josh’s gambling had grown out of control. He got a job as a salesman for a software company, working on commission. But his gambling would interfere with that job. “I made no sales,” he recalled. “I didn’t get a single paycheck.” Nevertheless, that fall the company sent Josh to a computer convention in Las Vegas. It was the kiss of death for a compulsive gambler. “The whole time I was supposed to be meeting people and pitching software, I was at the tables,” he said.

By the time he got to Las Vegas, the money he had made during his summer hot streak was gone. He left Austin owing his bookie $2,000. At eight o’clock on his final night in Vegas, down to his last $50, Josh started playing craps “for the first time in my life.” Twelve hours later he was ahead $6,500. But he couldn’t stop. He would finish four hours later—sixteen hours after he had started—with $4,000. “People were cheering my name,” he told me. “That isn’t good for someone who has a gambling problem. It was like the greatest time of my life.”

Josh’s hot streak wouldn’t last. Three weeks before Super Bowl XXVII, with all of his friends on winter break, Josh sat alone in his apartment, snorting some cocaine he had bought for the weekend. He smoked some marijuana. He stayed up all night formulating a go-for-broke strategy. The drugs gave him the nerve to wager some $30,000 that he didn’t have on a series of bets.

While the Houston Oilers were racking up a 32-point lead against the Buffalo Bills in the NFL playoffs, Josh Levine stood to lose the entire $30,000. Sitting in his apartment, which was now a disaster area, he worried first about his own safety, then about his family’s. He snorted some more cocaine. He calculated how much he could make selling all of his expensive things—the beveled-glass coffee table, the television, the leather couch, his compact-disc collection. He wondered which of his rich frat buddies could possibly front him some dough. But when the Oilers pulled the biggest choke in NFL playoff history, Josh was saved—sort of. At the end of the day he owed his bookie only $11,000.

For several weeks, Josh used his answering machine to screen his calls, refusing to speak to or call back the bookie. But one Sunday, while several of Josh’s roommates were watching a game, the bookie had had enough.

“Pay me or I’ll cut your f—ing balls off!” he screamed into the answering machine.

Josh was able to sell his things for $5,500. His bookie worked out a payment plan for the rest of the debt: Josh would direct all of his gambling buddies to him. But Josh balked at what he perceived as a devil’s compact. Painfully aware of gambling’s eternal truth—the bookmaker always wins—Josh didn’t want his friends to suffer his fate. He and the bookie came up with a new arrangement, in which Josh would direct his friends to the bookie and make 10 percent of their losses during the upcoming baseball season. He would receive the payoff, which he had estimated at $1,500, after the World Series. Josh planned to take his friends out for a raucous night of drinking on Sixth Street. “But,” Josh told me later, “my summer ended in the middle of the baseball season. ”

After his bloody playoff Sunday, Josh said, he stopped gambling. Reeling from his losses, he told his mother that he needed counseling for depression. A psychologist informed Josh that his condition was no different from that of any confused undergrad and prescribed a copy of Douglass Coupland’s Generation X. The literary prescription didn’t work. Josh fell further into a funk, embarking on a lifestyle that would lend credence to attorney Zimmermann’s insanity defense.

Josh said he lost the taste for gambling that February, but his debts were a constant reminder. He had sold most of his possessions and borrowed $3,000 from a frat brother. He ignored his bills—the $829.47 he owed for utilities and the $1,058 he owed Southwestern Bell—and had racked up $1,158.05 on his Visa card. In May his longtime girlfriend broke up with him. When his apartment lease expired that month, he lost his place to live. By day he would float from friend’s house to friend’s house, where he would sit and smoke pot and “talk about many things, namely our existence,” he recalled. Some nights he would leave Austin at four in the morning and ride his bike to his parents’ home in San Antonio. For two weeks he slept under the stars in Austin’s Pease Park. He shaved his head. Josh’s journal writings reveal his depression. “Do I truly want to be a writer?” he asked in his journal on July 21. “Do I truly want to be? I f— things up all the time and do not seem to have a habit, except for scheming and hustling. I believed I had more in me than that, but perhaps I am no better than the everyman.” Another entry, from July 19, 1993, says: “Today is my birthday. So much for that. What am I looking for? I have the problem of either being too good-looking or not good-looking enough. Twenty two and still dreaming. Hang on, Josh, hang on.” Three days later Josh wrote: “When did I change? Was it when I smoked more dope than my neurons could handle? Or when I realized I was a failure of unimportant circumstances?”

Josh should have graduated by the summer of 1993, but he was a few hours short of the required credits. His parents began to send him less money. He found a job as a midnight baker at the Kitchen Door but lasted only two weeks—the hours were too cruel. He struggled to make the $330 monthly payment on the loan from his frat brother.

Then, once again, ZBT came to the rescue. A pledge brother agreed to let Josh live in his apartment for the entire summer in exchange for Josh’s taking a computer science class for him. Josh continued to worry about how he would support himself after the summer. And in late July, after watching the movies Reservoir Dogs, in which a heist fails miserably, and Point Break, about a bank-robbing ring of surfers, he made a fateful decision: He would save himself by robbing a bank. Nothing else in life made sense.

Josh began a workout regimen to prepare for his crime. Every day he swam at UT’s main pool, rode his bike around Austin, or played basketball—and cased the First State Bank. He jotted notes about his plan on a yellow legal pad. “I am about to write down some ideas,” he wrote, “and by doing so I could be making mistake number one.” He noted that there were two cameras, one security guard, three tellers, and one manager at the bank.

He figured he needed two partners, one to drive the car and the other to disarm the security guard. He approached his close pledge brother Elliott Finebloom about the idea while the two were on a leisurely drive through the hills of Austin. Finebloom didn’t think Josh was serious and told him that the only reason he would even consider participating in a robbery was if he needed the money. Like most ZBTs, Finebloom didn’t need the money.

“[Finebloom] truly is worthless,” Josh wrote in his journal. Josh next approached another pledge brother, who had a gun, but he too refused.

After they had eaten lunch at Mad Dog and Beans near the UT campus, Josh dropped his idea on a third fraternity brother. “You don’t need to gamble,” Josh told him as he pointed toward First State. “You need something more exciting. Something more productive. You need to rob a bank. ” The friend told Josh to take him home.

Even though his friends refused to go along with the plan—none of them thought he was serious—Josh included them with code letters in his written outlines. In the journal version, Josh and “T,” equipped with ropes and grappling hooks for a surprise entrance, would meet in front of First State. Afterward, the two would flee two blocks south to Twenty-fourth Street, where another fraternity mate, “L,” would await. They would throw the bag of money into L’s open car trunk and split off in three directions.

On August 1 Josh wrote down a list of last-minute things he needed: “what to wear, what to say, what to do.” On August 16 he bought the camouflage mask and neoprene gloves at an Academy store in Austin. He got the Astra pistol through a classified advertisement in the Austin American-Statesman, telling the gun dealer he was a computer salesman from El Paso who had recently been carjacked. When he went to Red’s shooting range to try out his new purchase—he had never fired a gun before—he discovered that he had bought the wrong size bullets.

On July 25 he had written, “This project and K— [his ex-girlfriend] are the only things on my mind. If I do it and write K— a letter then there will be nothing on my mind. ”

I was the only ZBT who showed up for Josh’s sentencing on the morning of July 22, 1994, a month after his conviction. He wore a charcoal-gray suit and a gray print tie. He needed a haircut, and his eyes were bloodshot. As he waited for his sentencing, he stared straight ahead, sometimes appearing angry, sometimes listless. Barring a minor judicial miracle, he would soon start a long prison sentence. He fumbled nervously with a copy of Anna Karenina.

His lawyer, Jack Zimmermann, had argued that it was not Joshua Alan Levine who had committed the robbery but Josh’s fictional alter ego, Reynaldo Zak. The defense had a two-pronged burden of proof. Zimmermann had to prove that Josh was not only mentally ill, but also morally and rationally incapacitated during the robbery. Zimmermann relied on scientific evidence—namely, diagnoses after Josh’s arrest indicating that he suffers from bipolar disorder. Since his stay at Laurel Ridge Psychiatric Hospital in San Antonio, Josh has taken several antidepressants, including Prozac and Lithomate. Josh’s uncle and father have taken Prozac, and his grandfather had electroshock treatments.

Judge Sam Sparks said during Josh’s sentencing, “That ship didn’t sail. I agree with the jury. Mr. Levine robbed the bank probably for gambling debts or maybe to see if he could get away with it. … I sense not a hint of remorse from Mr. Levine.”

“I don’t know how to convince you how sorry I am,” Josh told the judge. “I’ll suffer for my sins every day of my life. I’m an internal person.” All that really mattered, he continued, was that his bipolar condition had been discovered. He would accept his sentence without bitterness, “because I’m a good person again. ” His mother cried.

Josh’s final gamble—and perhaps his biggest—didn’t pay off. Despite having no criminal record, Josh was given a 106-month prison term followed by five years of probation. As two U.S. marshals handcuffed him, there were no tears from Josh, only a request that he be allowed to take Anna Karenina with him. Today Josh is out on a $100,000 bond, pending an appeal.

“When I get out of jail, I want to be a skilled writer, a well-read writer,” Josh had told me at the Twin Sisters cafe. He had sounded resigned to prison. A little hard time might not be so bad. It would free him up to write Reynaldo’s story, which might make a literary classic, or at least a television movie. He had said he was looking for an agent. “Who knows? Maybe I’ll meet one in my ninth year in prison.

“I’m high on the career track I’ve chosen,” he had joked. “I’m high on life.” As he explained how he seemed predestined for prison—his grandfather was a Holocaust survivor, his father had once worked as a prison social worker—his voice rose excitedly, his eyes lit up. Just as they had when he explained the gambling philosophy that had won him $25,000 two summers before.

Alex Hecht is a freelance writer living in Houston.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Crime

- Austin