This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

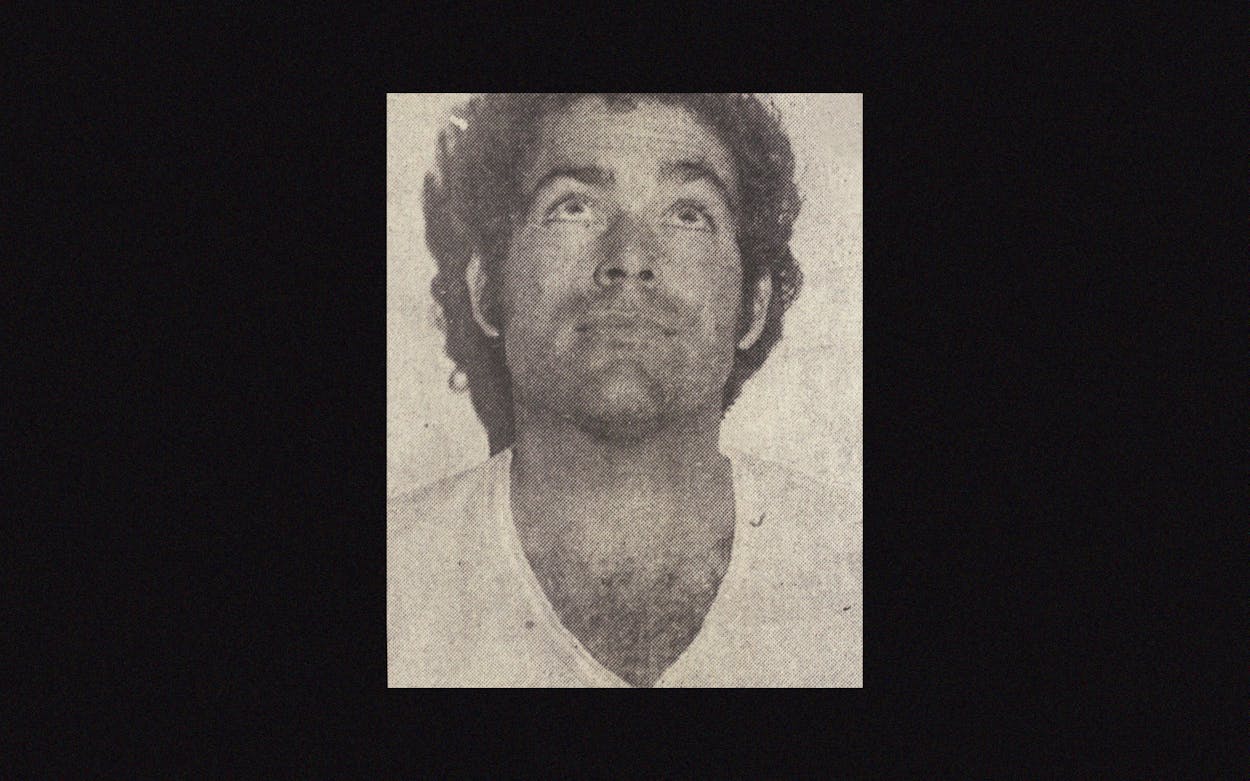

When the American inmates at Piedras Negras talked to Blake Davis, they sometimes caught themselves staring at the jagged, reddened scar that underlined the ridge of his jaw. Blake Davis was ebullient, powerfully built, well liked by the other Americans. Even in moments of discouragement he somehow managed a rueful smile. “Next week” was always the time of Blake’s anticipated departure from the Piedras Negras jail. He always had a scam.

Blake did not mind talking about his scar. He said he’d been arrested near Saltillo and charged with transporting 175 pounds of marijuana. For three weeks, Blake said, he was strapped naked to a bed while federales interrogated him, until finally he signed a Spanish confession he could not read. While he was in prison at Saltillo, Blake claimed he bribed a warden for $2000, but when the tunneling started the warden alerted the guards. Blake said he unwisely cried foul; the warden referred the matter to Mexican inmates who set upon Blake with crude knives and razor blades. Hence the scar. Blake’s tale of horror did not rate him special privileges in the Piedras Negras seniority system. When he was transferred there in August 1975, like all other new arrivals he took a seat on the floor.

When a Mexican attorney arranged his transfer from Saltillo, Blake thought he was destined for a federal prison in Piedras Negras called Penal. But Mexican officials claimed Penal was overcrowded, and they blamed Americans for a November 1974 breakout in which 24 prisoners tunneled to freedom. Blake Davis was thus assigned to the Piedras Negras municipal jail. Inside the jail were five cells for men, one cell for women, and a drunk tank, each of which measured eight feet by nine. The windowless cells contained four bunks, a toilet, a water faucet, and from six to twelve sweating, panting, claustrophobic prisoners. Mexican national inmates were eventually transferred to Penal, but the Americans waited for enough seniority to occupy one of the bunks. When they moved around their cells they shuffled. They never breathed fresh air, never saw the sky. The lights of the jail were never turned off, so their only concept of day and night came from the jail kitchen, which provided gruel in the morning, soup at noon, beans and tortillas at dinner. The Americans depended upon friends to bring them vitamins and food. After a few months their teeth began to decay and their hair began to thin. They passed the time playing scrabble, backgammon, studying Spanish. Two or three performed yoga and isometric exercises. Though the Americans inside hated and feared Mexican cops, they had a certain empathy for the jail guards, who were poor men working for five or six dollars a day and were helpless to do anything about the crowded conditions of the jail. The guards also seemed to understand that the Americans were under severe mental and emotional stress, prisoners of a foreign government and a foreign system of justice. Certain liberties were in order. Hard drugs could be smuggled past the guards, and the Mexican fink assigned to each cell containing Americans often operated a marijuana concession. Sometimes the guards allowed women to join the men in their bunks or in the privacy of the shower room. But now and then the powder-keg tension of the jail would explode. Some American would faint, his skin would turn the shade of alabaster, and the other Americans would start shouting angry demands for medical attention.

Except for weekenders in the drunk tank, all the American inmates were alleged narcotics violators. Under terms of the Mexican Napoleonic Code, any felony suspect caught red-handed, in flagrante delicto, can be held, interrogated, and denied access to an attorney for three days. If, after six days, a magistrate concludes that evidence warrants a trial, and the maximum sentence of the alleged offense is more than two years, a suspect can be held up to a year before he is tried. Even if a suspect proves in an amparo court of grievance that his Mexican constitutional rights have been violated, the charges against him still stand. In January 1975 the Mexican government enacted a law that denied narcotics suspects any kind of release on bond. From the standpoint of the Americans in the Piedras Negras jail, Mexican law was a stacked deck. Only Davis had actually been convicted, but the rest of the Americans never talked about waiting for trial. They always said they were waiting for sentencing.

Blake Davis and the other Americans knew that a California congressman named Pete Stark was spearheading a House subcommittee hearing on the fate of 600 Americans in Mexican jails, but they placed very little trust in the United States government. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) trains Mexican narcs, analyzes Mexican confiscations in its Dallas laboratories, stuffs American dollars into the Mexican control agencies at the rate of $14 million per year. Operation Cooperation, American officials like to say, is designed to disrupt the guns-for-heroin trade. But the American inmates claimed the barber-shirted federales busted any American they possibly could, by whatever methods, while their DEA benefactors applauded. It was no longer easy for American prisoners to buy their way out of Mexican jail. One of the American inmates at Piedras Negras theorized that nothing had really changed: the favors of Mexican mordida still went to the highest bidder—the United States government.

Once a month U.S. consular officials came to the jail; one of those callers was Leonard Walentynowicz, the administrator who represented the State Department at the congressional hearings. But the American inmates were in no mood to wait on Washington. Every prisoner had a plan. One considered smuggling in hydrochloric acid on visitors’ day to weaken the bars of the shower room. Another wanted to blow a small hole in the roof. Another pinned his hopes on a brother-in-law who worked for the CIA. The most dubious scheme involved advance payment to the Mexican secret police, who would then assist the escapees through a shower room window.

Blake Davis was king of the freedom schemers. For six months his father in Dallas had been trying to finance a Piedras Negras jailbreak. Every twelve hours, at six o’clock, the inmates were taken from their cells into the corridor for a lista. While the guards called roll, counted heads, and inspected the cells for signs of tunneling, the American inmates exchanged notes. They slept with their clothes easily accessible and tried to raise money through friends on the outside. Tuesday and Wednesday were the most likely nights, for there was less drunk traffic at the jail. Inevitably, the rumors reached the ears of the Mexican guards. One day in January an American tough recruited by Blake’s father signed the visitors’ register, submitted to a frisk by the guards, and came back to Blake’s cell. The American whispered through the bars that the jailbreak was on. Some of the American inmates altered their sleeping habits so they would always be awake in the hours after midnight. But when the American returned to Piedras Negras, he passed word the next visitors’ day that the break was no longer possible: armed guards were now circling the block and maintaining a lookout on the roof of the jail. Some of the inmates grew tired of constant anticipation. Every time the Coke machine noisily dispensed a ten-ounce bottle they wondered if commandos had broken down the door. After two months of breakout rumors, the guards also tired of hearing them. A new comandante ordered a search of the prisoners’ possessions, but told the warden that the guard on the roof was no longer necessary.

Blake Davis remained optimistic, for the alternative to optimism was exceedingly grim. He had lost 25 pounds during his incarceration. His body was covered with boils, and a cyst at the base of his spine was seeping pus. Poison from an abscessed tooth descended with his saliva and gave him a stomach ache. Blake Davis had served only two years of a ten-year sentence. He did not think he could survive eight more years in a Mexican jail.

In the late forties Sterling Blake Davis, Sr., introduced the limp-wristed flair of Liberace to the macho world of pro wrestling. While his old Houston crony, Gorgeous George Wagner, made a fortune with the routine on California TV, Dizzy Davis sported colorful, hand-sewn robes and dispensed flowers in the smoky arenas of Texas and Mexico. Sometimes called Gardenia Davis, he was a better wrestler than Wagner.

Davis’ luck since those days had been a carousel ride. By 1972 he owned a large home on the east shore of Dallas’ Lake Ray Hubbard, but his health was failing, and he was only 58. One of his sons seemed to be adjusting nicely to middle-class adulthood. The other, Sterling Blake, Jr., nicknamed Cooter, was doing time in a federal penitentiary for possessing 770 pounds of marijuana in Arizona.

The old man would soon be in a heap of trouble himself. In November 1973 he was named in a thirteen-count federal fraud indictment and was tried in February 1974 in the Dallas courtroom of Judge Sarah T. Hughes. Testimony in that trial portrayed Davis as a shuck and jive artist who convinced 70 customers that bullfrog farming was the wave of the future. One investor testified that Davis falsely claimed to own a 650-acre frog farm in Arkansas, from which in a single year Rice University research scientists bought 9000 bullfrogs—at $16 a frog. Frog distributors came from as far as Iowa and Florida to testify that Davis and two other men sold them a $3000 package of goods that included two portable swimming pools with inefficient filters, a few frogs, an instruction manual, and a piece of vibrating sheet metal called an automatic feeder. The instruction manual said bullfrogs could be taught to feed in captivity if they were offered a fare of bouncing maggots, and then rabbit food, on the vibrating sheet metal. One distributor said he hung a rotting armadillo over the feeder to keep the frogs supplied with maggots. Another testified that his wife watched for signs of progress with binoculars from a nearby tree. Most said they eventually set the starving frogs free.

At the trial Davis contended the feeder worked perfectly for some of his more prosperous clients, but the court remained unconvinced. “Now I heard the evidence and I don’t think the feeder is working,” Judges Hughes replied. After the jury found Davis guilty on ten counts, Hughes told him, “You are one of the best con artists that has appeared before me.” She ordered him to make restitution to his former customers, fined him $10,000, and sentenced him to five years, followed by five more years probation.

Davis, who carries the long vertical scar of open-heart surgery, pled ill health. After studying the doctors’ affidavits, in May 1974 Hughes probated the remainder of Davis’ five-year sentence. That very same month Davis’ son Blake, paroled by then on his Arizona pot conviction, was arrested 150 miles deep in Mexico and charged with possession of marijuana. Sterling Davis felt like a man accursed.

To pay his legal fees Davis had to sell most of the two acres he owned on Lake Ray Hubbard. His probation officer vetoed a couple of ideas for new employment. Finally Davis offered his services to the administrator of a noncredit educational institute in Dallas, explaining that in the frog farm episode he had been a mere management consultant deceived by the two salesmen. Davis convinced the administrator he had valid degrees in psychology and experience as an industrial psychologist. At the institute Davis tutored night students on meditation techniques allegedly developed by long-lived Andean Indians. To avoid incurring the legal wrath of the TM organization, Davis called his course Transcendental Relaxation. In January 1975 he applied for a state license to practice clinical psychology. The board of examiners informed him that before he could take the qualifying exam, two years of experience supervised by a licensed psychologist were required. Davis found a psychologist who would sponsor him. Extremely secretive about his personal finances, Davis somehow put his hands on enough money to furnish an office on Northwest Highway with a $1500 stereo that played soothing music and a vibrating chair which gave the person sitting in it a massage.

At the same time, Davis was trying to get his son out of jail. He pursued embassy channels to no avail and developed a very low regard for Mexican attorneys. To his surprise, however, he learned that if nobody was hurt, and no property was damaged, there was no law against jailbreak in Mexico. After Blake was transferred to Piedras Negras, Davis started looking for ways to raise money, including efforts to involve friends and families of the inmates. He put out a feeler which moved through an underground of Dallas bars, drive-ins, and all-night restaurants. It was not a very attractive offer. The jailbreakers stood an excellent chance of getting killed, and if they were captured by the Mexicans, they were as good as dead. If they killed any Mexicans while freeing the inmates, the American government would probably extradite them. The money Davis offered was insufficient to attract mob professionals. Davis thus interviewed a long line of maniacs and scoundrels. One group Davis rejected wanted to storm across with enough explosives to start a war. He advanced money to another gang of small-time heavies who bought guns and an El Camino pickup, then partied until the money ran out in San Antonio. Davis had high hopes for the assault team that approached his son inside the jail, but they were frightened off at the last moment by the beefed-up security. He had begun to wonder if jailbreaks happened only in the movies.

At his Northwest Highway office on Monday, February 16, Davis gazed across his desk at another prospective jailbreaker. The man did not look like much of a commando. He had an enormous belly, and when he opened his mouth there was a dark gap where his two front teeth should have been.

Don Fielden was a Marine without a mission, a truckdriver without a rig. After moving to Dallas from the northeast Texas town of Gladewater, Fielden had dropped out of Woodrow Wilson High School and joined the Marine Corps in 1966. Assigned to the infantry during boot camp at San Diego, he underwent field radio training at Camp Pendleton and drew orders to join the First Marine Division in Viet Nam. “They’d been telling us all along that this was a police action,” he recalled much later. “They instilled that thought so deep in my mind I expected to go over there and use a .45 and a nightstick. Patrol the streets. The first night I was in Da Nang, they shelled the hell out of us. I thought, man, I ain’t never seen a cop go through this shit.”

Fielden explored the Vietnamese countryside by helicopter and combat patrol. “I was able to condition my mind to where it was like I was back home squirrel hunting,” he said. “Except these squirrels were shooting back. I don’t have bad dreams about killing people over there. I’m not ashamed of it. It was a job my country told me to do.” Fielden helped ward off enemy attacks during construction of the air base at Phu Bai, then took his R&R leave in Japan. Nineteen days before he was scheduled to rotate back to the States, he was pulling radio watch in a sandbagged bunker near the DMZ. After finishing his watch, Fielden stood at the door of an unfortified wall and gazed longingly at the two-man privy positioned a few yards away. He paused in the doorway to monitor a radio message; at that moment a stray communist rocket scored a direct hit on the two-holer. Shrapnel gouged a chunk out of Fielden’s shoulder and nearly severed his right leg below the knee.

At the U.S. Naval Hospital in Corpus Christi, Fielden worked in the Marine liaison office and extended his enlistment for a year. He soon learned that antiwar sentiment was running deep; even some of the sailors at Corpus Christi treated him like a murderer of children. On his first leave he found that things were no better in Dallas. Fielden’s favorite times during that period were spent in the company of other convalescent Marines at a bar called the Town Pump. But there was scant future in the Marine Corps for a sergeant with a chronically aching leg. Fielden was severed from active duty in 1970 with a purple heart but no disability pension. In 1972 he received his honorable discharge in the mail.

Back in Dallas, Fielden sometimes told people that the hideous scar on his calf was the result of a motorcycle accident. He bought a Corvette and entertained new acquaintances with his jovial banter. But he was drinking heavily, and his weight pushed far past 200. The father of two children, he soon would be able to report he had been divorced three times.

Fielden was becoming a tough character in a tough town. The Marines had trained him to function in a world of total violence, where the ethic of work was survival. No civilian experience matched the overcharged excitement of Viet Nam, but he didn’t stop looking. He drove a truck and moonlighted for a collection agency that fronted as a nightclub janitorial service.

On the night of March 3, 1975, the freeway driving habits of a Dallas municipal employee so outraged Fielden that he fired off a couple of shots from his pistol—clean misses—while Dallas Cowboy flanker Golden Richards witnessed the incident driving in an adjacent lane. The grand jury no-billed Fielden when nobody chose to testify.

Fielden was relatively happy as a long-haul truckdriver. He liked his life on the road; trading truckstop stories about bears and tourists reminded him of the masculine camaraderie of the Marine Corps geedunk beer halls. But then on December 23, 1975, Fielden returned from a trip and parked his truck on the lot of his Dallas employer. When he returned the next day his boss told him, “We can’t use you anymore. You’re fired.”

“Merry Christmas,” Fielden said to himself.

Fielden was not making it on the outside; he remained a casualty of the Viet Nam War. As a teenaged recruit Fielden never questioned the Marine Corps line. He labored torturously for contemptuous drill instructors who told him he would “never make a pimple on a Marine’s ass.” Fielden had proved himself a Marine at home in the barracks and overseas under fire. Now he was failing in a world that did not care if he had made the Marines. Out of work, out of family, running out of money, Fielden was desperate for drastic changes in his life. During the day he wasn’t doing much of anything. At night he hung out in north Dallas trucker bars and discos—the world in which Sterling Davis’ jailbreak offer was circulating. A friend explained the situation and gave him the doctor’s phone number. On February 16, 1976, Fielden kept an appointment in the blue and silver office building on Northwest Highway.

Fielden had a very stonefaced way of listening to people. His chin jutted out and his mouth turned down: characteristics shared by the Marine Corps mascot, the bulldog. In the office Fielden listened as Sterling Davis recounted the story of his troubled efforts to free his son. Davis said that he’d studied in Mexico; a diploma on the office wall indicated he earned his PhD from the University of Mexico in 1951. Fielden did not speak Spanish, and he asked Davis to provide him with the Spanish equivalent of “get your hands up” and other key phrases. The doctor stammered and changed the subject.

Fielden earned his high school equivalency certificate during his tour in the Marines. He respected men with superior education. He did not respect men who feigned academic credentials. Fielden pegged the old man as a con, and he had scant compassion for busted dope dealers. But he said he would free the doctor’s son for $5000 and expenses, reimbursed afterward. It was a job, a mission, almost like the Marines. In a dull civilian world, where he did not quite fit, it was a chance to rejoin the action. You can take the man out of the war but you can’t always take the war out of the man.

Fielden spent most of the third week of February in Eagle Pass, reconnoitering his combat patrol into Mexico. Fielden was pleased by some of the things he saw. The Piedras Negras jail was only three blocks from the Mexican tollgates at the International Bridge. On visitors’ day he took Blake Davis some food and called him by the family nickname Cooter. Blake knew immediately why Fielden was there. Fielden thought the jail looked like the set of an Old West movie. The cells were locked with hasps and chains that could be cut with heavy-duty bolt cutters. But the jail sat far back on its lot, adjoined on both sides by the walls of buildings that extended to the street. When Fielden stepped out of the Piedras Negras jail, he was looking at the rectangular dimensions of a trap. If he had been a history buff, he might have reflected that Emiliano Zapata rode into a similar Mexican trap. Reluctantly, Fielden concluded he would need another man.

Mike Hill was broke and he was looking for trouble, if trouble would get him out of Dallas. Hill had been scraping a living off the streets of Dallas since he was thirteen years old, and at 32 all he had to show for it was a Chevy Step-Van painted reflective silver. He spent part of the winter of 1976 sleeping in his van.

The son of alcoholic parents, Hill stopped going to school when he started living alone in a deserted fire station. He subsisted at first on a diet of soda pop and bread, then stole a bicycle so he could take a delivery job. During the rest of his teens Hill’s residence alternated between the homes of friends and the state reformatory at Gatesville. Hill always ran away from Gatesville. He couldn’t stand the feeling of confinement.

In 1965 Hill was convicted of burglary but his sentence was probated. Over the next decade he was jailed and hauled before grand juries on an assortment of charges but was never indicted. A marriage produced two daughters before it ended in divorce. He bought used cars wholesale, then sold them through the classifieds. He ran a wrecker service that rousted him out of bed at all times of the night. Then in 1972 Hill discovered marijuana. When it wasn’t feeding his paranoia, a marijuana high dulled the sharp edges of Mike Hill’s world. He sold his business, motorcycled to Florida, and returned to exploit the Dallas tow-away ordinance. A fleet of independent wrecker operators hauled cars away from private property posted with warning signs, then delivered the cars to a lot leased by Hill. Hill paid the drivers $25, then charged the owners of the impounded autos $43 in cash. Perfectly legal. Ensuring order at Hill’s lot were snarling dogs and a gang of shotgun-toting cronies. In May 1975 an ad department employee of the Dallas Morning News detailed the treatment in a memo to reporter Dave McNeely, who went to the lot with newsroom comrade Dan Watson. Gruff and burly, McNeely is the kind of reporter who once got into a fistfight as a result of his questions. He does not scare easily, but Mike Hill frightened him.

The reporters’ story placed Hill in the center of a storm of bad publicity, but worse news was yet to come. Hill’s drivers towed away the car of Dallas Mayor Pro Tem Adlene Harrison. One driver tried to remove the car of Dallas undercover narcotics agents who were parked at a closed filling station observing a progressive country nightclub on Cedar Springs. The narcs ordered the wrecker driver away, and the driver called Hill. When Hill arrived at the site in his van, the narcs radioed a vice-squad officer for assistance. The ensuing argument ended, inevitably, in Hill’s arrest. In Hill’s van, Dallas officers told reporters after the incident, were a loaded derringer, a loaded pistol, a dagger, a shotgun, and two baseball bats. Adlene Harrison proposed a new tow-away ordinance to the city council, and a misdemeanor gun conviction was added to Mike Hill’s growing Dallas Police Department record.

Through it all, Hill remained eminently likable. A blond mustache concealed a beer-bottle scar, the bridge of his nose was enlarged by numerous fractures, and there was something tense and hard about his eyes, but when Hill laughed he was handsome. He was a good storyteller, and women found him attractive. He stood nearly six feet and was muscular, with only a little flab above his belt. He had an odd, slouching stride, shoulders hulking forward as he walked. Mike Hill was a familiar Texas character: the tough guy good old boy. When he drove his van into the lot of a favorite hangout the last week of February, he wasn’t necessarily up to no good. He was just passing through. A friend who also knew Don Fielden stuck his head in Hill’s van and grinned. “Hey boy. You wanta go to Mexico?”

Hill was intrigued; the whole idea seemed so, well, bizarre. Besides, he needed money badly and an expense-paid trip to Mexico sounded like a vacation. The two men arranged to meet on Saturday night, February 28, at the Denny’s on Industrial Boulevard. By this time Fielden was desperate for a partner. Few men had been interested in the deal before Hill: the risks were mortal and the take-home pay was only $2500. That night Hill listened to Fielden’s story and studied his plans for the breakout while Fielden drew pencil sketches on paper napkins. Fielden kept emphasizing, “It’s not against the law, as long as you don’t hurt anybody it’s not against the law.” Hill avoided making a commitment for a while, but when Fielden said he wanted to leave on Monday, Hill replied, “What’s wrong with tonight?” Fielden said he had to get some traveling money together and agreed to leave the next day.

Driving south in Fielden’s Ford they quickly got on each other’s nerves. Hill was a coffee freak, so every few miles Fielden had to stop at a cafe. Hill’s legs were numb from the frigid gale of Fielden’s air conditioner. Fielden wanted to talk about the break; Hill wanted to watch the passing countryside and think about getting laid in Mexico. Hill asked Fielden how much money he had raised, and his partner muttered, “A hundred dollars.” Hill thought: a hundred dollars? I thought I was getting in on a big-time deal. In the car were Fielden’s sawed-off shotgun and Hill’s twelve-gauge pump. As they drove farther south it became more apparent that Fielden intended to stage the raid without any further delay.

“Uh,” Hill said, “I thought we were just gonna go down there and kinda look at it.”

The next morning, March 1, Fielden and Hill paid nickel tolls at Eagle Pass and walked the International Bridge across the Rio Grande, on that day a shallow, muddy stream that swirled against the steep bank on the Mexican side. Hill had always been enchanted by the culture of Mexico. He liked the food, the music, the brown-eyed raven-haired women. Hill was excited as he passed the Mexican customs inspector and his sign that read TERMINANTEMENTE PROHIBIDA: La importation de armas y cartuchos . . .

Hill’s stomach convulsed with fear when he saw the jail. It was too well guarded, too far back from the street. Back in the Eagle Pass motel room, they considered diverting the Mexican cops’ attention with fires or explosions, but whenever Fielden started talking too intently about the break, Hill rolled a joint and smoked it. On Tuesday, March 2, they watched the jail from a tamale stand and inspected the streets in the vicinity, attracting a following of shine-boys, pimps, and guides. Everything still looked wrong to Hill. The street in front of the jail ran one way in the right direction, but the road was extremely narrow. Cops stood in front of the jail. Hill and Fielden weren’t even sure Blake Davis was still in the Piedras Negras jail.

Returning to the motel, Hill talked by phone to Sterling Davis for the first time. The doctor in Dallas “sounded real positive about not sending anybody any money,” and he only presumed that his son had not been moved. Fielden wanted to stage the break while he still had money to pay the motel bill. At midnight Hill put on his gloves and drove the Ford across the bridge, but as Fielden inspected the sawed-off double-barrel, Hill continued to argue strenuously against going through with it. Hill said he didn’t even know what Blake Davis looked like. If Fielden got killed, was Hill supposed to run in the jail yelling which one of you guys did we come after?

The argument was interrupted when a Piedras Negras patrol unit pulled up behind the Ford and turned its flashing lights on. Twisting around to see if the cops got out with pistols drawn, Fielden reached for the door handle and warned, “We’re gonna have to take ’em out.”

“Wait a minute,” Hill cried, grabbing for Fielden’s arm as one of the cops got out of the car. “Let’s see what he wants, and then we’ll kill him.”

As the Mexican cop approached, Hill extended a hand toward him and said, “Señor, which way to Boys Town?”

The cop’s gaze focused on Hill’s grimy glove. “Ah, señor,” he said. “Follow me.”

Trailing the patrol unit, Hill fell far enough back that Fielden was able to ditch the guns in some bushes. In the bordello Hill and Fielden thanked the cops and went into one of the bars. Hill only had $20, but he was so happy he bought one of the whores several drinks.

Wednesday was visitors’ day at the Piedras Negras jail. A guard frisked Fielden and Hill and unlocked the door which led back to the prisoners. A stocky man with curly hair greeted Fielden from the first cell. Fielden stood shoulder-to-shoulder with other visitors outside the bars as he whispered instructions to Blake Davis. Hoping to gain some insight into the man he was going to rescue, Hill spoke briefly with Blake, but he wanted badly to get out of that jail. Hill was convinced that the purpose of their visit was transparently obvious to the guards; compared to the other visitors, they looked like gangsters. And Hill had spent enough time in American jails to react emotionally to the horror of this one. The odor in the jail was appalling. The visitors were panting and drenched with sweat. Recalling the expressions of the prisoners’ faces, Hill later remarked, “Have you ever seen a drowning dog?”

In the motel room Hill and Fielden argued again. Hill wanted a third man in the car with a walkie-talkie. “I’ve got to get this deal done,” Fielden finally exploded. “I never took a deal that I didn’t do. All I want is somebody to watch my back. I’ll do it.”

“Your back!” Hill cried. “I’m thinking about my butt, I’m thinking about my whole damn body!”

Fielden drove when they crossed the bridge after midnight. As they headed for the brush where they had stashed the guns, Hill was talking fast and furiously. They’d been hanging around the jail for three days; the Mexican cops had to know something was up. They didn’t have enough gasoline money to get back to Dallas. “I don’t wanta do it tonight,” Hill said. “My karma’s not right.”

Fielden was more confident, but their lack of money worried him, as did Hill’s queasiness. Fielden knew from his combat training that in an operation like this, both men needed conviction, if not total confidence. Hill’s reluctance could get them both killed. After they retrieved the guns they came upon the same cops who had stopped them the night before. This time Fielden got out of the car. “Well, we’re through in Boys Town,” he told the cops. “How do we get out of here?”

The next morning a friend wired Fielden $50. They paid the motel bill, gassed up the Ford, and headed back to Dallas. On the way they had a flat. Fielden was disgusted, uncertain he could ever count on Hill. But he had no other partner in mind; in hiring Hill he felt he’d already scraped the bottom of the barrel. Hill told Fielden he would proceed with the breakout only if they could recruit a third man and if they had enough money for their expenses. Fielden assigned Hill the task of finding the third man. As a token of good faith, Hill said he could probably raise the money if Fielden could not.

On Saturday, March 6, Hill met Sterling Davis for the first time in the office on Northwest Highway. Hill was impressed by the verbal assurance of the craggy-faced man, but something about the office made Hill think the doctor “hadn’t been there too long.” Davis showed Hill a photocopy of a check for $5000, but again refused to advance any expense money.

Hill proceeded with marked ambivalence. In the presence of Fielden, he offered the lookout job to a hulking friend. But something—perhaps affection, perhaps doubts about the man’s reliability—made Hill ask his friend after Fielden was gone: “You remember those wetbacks you took on with a ball bat? They paid me two thousand dollars to get you across the border.” The friend quickly withdrew. With him removed from the picture, Hill next offered the job to Billy Blackwell, a stocky eighteen-year-old with shoulder-length brown hair who had previously worked for Hill in the wrecker business. Blackwell now mowed lawns for a living and said he could not read or write. Billy lived with a teenaged brother but he ran with a tough older crowd. To Blackwell, Mike Hill was a figure to admire, to emulate. Hill often teased his young protégé. “Stick with me, Billy, and we’ll go places,” he joked. “Let’s you and me rob a bank.” Billy laughed at the banter and always tagged along; Mike hadn’t gotten him in trouble yet. Hill was willing to trust his life to the eighteen-year-old. He knew that Billy Blackwell’s loyalty was absolute.

Having fulfilled his responsibility of hiring a third man, Hill again stalled. By now both men had begun to feel some sense of personal obligation to the Piedras Negras inmates, but Hill would have welcomed a development that took him off the hook. “I was trying to stay alive as long as I could,” he later explained. He called Fielden and asked if he had been able to raise the money. Sounding dejected, Fielden said he had exhausted all his possibilities. Hill regretted his offer to raise the money himself. He considered telling Fielden that his monetary well had dried up too, but he hated to lie his way out of a commitment. He kept remembering his visit to the jail—how it looked, the drowning-dog expression on the prisoners’ faces. So instead he lied to raise the money. He told a business creditor that repossession of a tractor-trailer rig in Mexico was worth $10,000 to himself and another man. With considerable misgivings, the creditor loaned Hill $1000, using the silver van for collateral, and said he was also willing to extend enough money on a separate loan to put Hill back in the used-car business. The offer provided Hill with a monetary out; he could pay his bills now without Sterling Davis’ money. But Hill had become intrigued by another possibility. An electric-haired American in the cell next to Blake’s had gotten word to Fielden that he would pay equal money if he came out too. Fielden at first intended to bring out only those two men. Hill wanted to free all the prisoners. If every freed American voluntarily came up with $5000, they were talking about a potential haul of more than 50 grand. Though Hill was more cautious than Fielden, he craved adventure, too. All those factors tipped the balance in favor of Hill’s participation. He borrowed a spare for Fielden’s Ford, walkie-talkies, new gloves, and blue ski masks with red insets on the faces. Hill was not an educated man, but he understood guerrilla psychology. They would go across in dark clothing, relying on the element of surprise. Mexican cops did not often encounter men with shotguns and ski masks.

On Wednesday morning, March 10, Hill phoned Blackwell and said, “Get your clothes together, Billy. We’re going.” Hill smoked a joint as he waited for his partners, and when Fielden’s Ford pulled up outside the metal prefab apartment Hill looked out and saw a man with sandy razor-cut hair. That’s not Billy, Hill thought, then remembered that Blackwell had been instructed to wear a short-hair wig.

Hill had described the project to Billy in extremely vague terms. He suspected that his young friend thought they were actually going down to repossess a truck. As they drove south, Hill tried to impress Blackwell with the seriousness of the situation. “Billy, what it boils down to is we’re going to war down there, actually.”

Billy swallowed hard. “Well Mike, don’t you think I need a gun?”

In Waco Fielden bought a bottle of scotch. Hill knew he had to be straight when he crossed the Rio Grande, but in the meantime he and Billy were passing joints. As darkness fell and they passed through San Antonio, tension in the Ford began to build. “Why don’t you quit smoking?” Fielden finally said.

Hill thought about it for a minute and said, “Well, hell, you’re drinking.”

They checked into the Holly Inn in Eagle Pass and watched TV until it went off. Billy got extremely quiet when Hill and Fielden pulled out the guns and ski masks. Fielden briefed Blackwell on each of the five checkpoints, and shortly after 2 a.m., Thursday, March 11, Billy wrapped his jacket around the walkie-talkie and began his lonely walk across the International Bridge.

Hill and Fielden gassed up the Ford and returned to the motel, where Hill stashed the rest of his money, about $400, in his shaving kit. He didn’t want the Mexican cops to have it. Near the bridge again they tried to raise Billy, but a Mexican CB operator broke in over them. Finally Billy called from the vicinity of the jail: “Ringo, this is Sam. There’s a bunch of activity over here now. Cars coming in and out.”

“OK. We’ll call you back in ten minutes.”

Waiting at the border, Hill took a couple of swallows from Fielden’s bottle of scotch. A few yards away two Eagle Pass patrolmen were conducting some kind of investigation. Hill and Fielden pretended to study a map, and the cops drove away after giving them a long look. The cops circled the block, circled the block again. Hill got out and went over to the patrol car. “We been trying to read that map for an hour,” he told the cops. “How do you get to Boys Town?”

The cops laughed, gave Hill directions, and drove away. In the car Hill and Fielden were unable to raise Blackwell. “They must’ve got Billy,” Hill finally said. “Let’s go on across.” Crossing the bridge, Hill swallowed a tablet of speed.

Fielden’s intelligence report anticipated three Mexican cops at the border, one in the small park behind the tollgates and three at the jail. At the border Hill saw at least six uniformed officers, all impressively armed with chromed sidepieces. After clearing Mexican customs, Hill turned off the plaza and tried to circle through the maze of narrow streets to the jail. Very quickly they were lost. A carload of Mexican youths pulled up beside them. Hill and Fielden knew that the street in front of the jail led to the bordello. “Pinoche, pinoche,” Hill cried. The Mexican youths laughed and motioned for the Ford to follow.

After tipping their guides a dollar, Hill and Fielden at last raised Billy. “Six of the cops just left,” he radioed. “There shouldn’t be but three in there now.”

They picked up Billy a block from the jail, and Hill parked the Ford one parking space away from the jail lot. “If you have any second thoughts, if your karma’s not right . . .” Fielden began, but Hill was putting on his ski mask, too.

On the sidewalk Hill did a double take as he passed the car parked in front of the Ford. “Don’t freak out,” he whispered to Fielden, “but there’s a cop asleep in that car.”

Fielden froze.

“What? Where?”

Headlights fell upon them from behind. Fielden concealed the sawed-off with his bulk and turned his face away; Hill stuffed the pump in a long flower pot on a wall, ripped his mask off, and turned to face the approaching motorists. Just another carload of horny American boys, Hill sighed to himself with relief. He put his ski mask back on and stared across the street. In the police auto pound he saw cars with all the doors flung open. Paranoid flash: they’d been set up, cops were lying down behind the seats! Fielden forged ahead with the tense determination of a Marine about to plant the flag at Iwo Jima. Hill followed at a trotting walk, searching the rooftops for soldiers with rifles. When Fielden grabbed the handle of the jail door, for the first time Hill was absolutely certain this deal was going down.

Fielden had been studying a Spanish dictionary, but he was still not certain how to say “get your hands up.” “Palmo asente!” he yelled as he burst through the door; when he saw the inside of the jail, he thought god damn, we’re gonna have to teach that boy to count. Through Hill’s mind sped an image from a favorite movie: Newman and Redford, Cassidy and Sundance, running toward a lethal hail.

Behind two counters five guards and five police officers were interrogating an eighteen-year-old Mexican girl who’d been jailed on drug charges but claimed membership in Liga 23 de Septiembre, the cop-killing terrorists of the Sierra Madres. When Fielden and Hill ran through the door the disbelieving cops froze for an instant, then scattered in ten different directions.

“Freeze!” Fielden bellowed, and gave one cop a whack with the shotgun when he proved reluctant to surrender his pistol. Hill vaulted across the counter, and the Mexican stenographer fell out of his chair in front of him. Fielden looked up after relieving the first cop of his gun and saw that two more had their pistols drawn and aimed. “Huh uh,” Fielden warned, and the force of the sawed-off twin barrels won out: two more pistols dropped to the floor. Staring at the bore of Hill’s twelve-gauge, two cops raised their hands; as if he were bailing water, a third tried to dislodge his pistol from his holster. Then Hill saw the M-1 propped against the wall. Easing toward the rifle, Hill glimpsed the toe of a man’s shoe just behind him. He yelled and wheeled his twelve-gauge around. The cop reeled back in terrified surrender. Mike Hill had come very, very close to committing murder.

The element of surprise had worked. They had subdued the cops without firing a shot, which was essential if they had any hope of escaping death, capture, or at best, extradition. Fielden hurried to the barred door which led back to the cells and popped the chain with the bolt cutters. While Hill watched the cops, Fielden encountered the unarmed guard who tended the cells and a Chicano prisoner who was outside his cell when the shouting started. Fielden ran to the first cell and weighed down on the handles of the bolt cutters. But this chain broke the jaws of the bolt cutters. Fielden looked helplessly through the bars at Blake Davis. Davis groaned, “Oh, shit.”

“Get the keys,” one of the inmates recommended. “How do you say keys in Spanish?” Fielden snapped. “Llave,” the inmates clamored. “La llave.”

What were they saying? Yobby? The Chicano inmate lashed the unarmed guard with the broken chain. The guard finally got the message when Fielden held the sawed-off to his head. Fielden walked the guard to a desk in the front office, then came back and unlocked Blake Davis’ cell.

Hill started herding the cops down the corridor toward the cells. The eighteen-year-old girl looked at Hill and said, “Me too?”

For all Hill knew the girl was a cop. “You too, baby. You better move.”

“Me too?” the girl said again.

Hill raised the shotgun to the girl’s eye level and she followed the cops down the hall. Blake came out front and Hill handed him the Mexican M-1. While Blake watched the cops, Fielden unlocked the two remaining cells containing American men. One imprisoned Frenchman opted for the security of his cell, but the Mexican nationals were extremely willing to share the fruits of American labor. One of the American inmates ran around to the back and pried a weakened bar until the women were able to wriggle free. At least two dozen inmates were soon milling in the corridor, shushing each other and trying to contain their excitement. “Nobody goes out before us,” Fielden ordered. “There’s a man out there who’ll cut you in two.”

The Chicano who had attacked the guard broke for the front. Blake shouted a warning and leveled the M-1, but the Chicano reached Hill, who’d been pacing nervously and exhorting Fielden to hurry up. In the confusion, Hill forgot to snip the phone wire. The Chicano asked Hill if he had any more guns. Hill noticed the man had blood on his head. He handed over a Mexican pistol, and the Chicano kicked open an office door, revealing two federales who had been interrogating his wife before the jailbreak started. Since then they had been hiding quietly. The Chicano proceeded to pistol whip the federales noisily.

“Who was that?” Hill asked Blake, who had followed the Chicano up the hall.

“He’s all right,” Blake replied, then returned to the back. Suddenly Billy’s voice came from the walkie-talkie: “Mike, you got two coming through the door.”

Heart pounding, Hill crouched behind the counter and waited. The Mexican cops never arrived; opening the door they’d seen an American inmate carrying a carbine. “Billy, where are they?” Hill finally blurted into his walkie-talkie.

“I don’t know, man. They left.”

Inside, Fielden herded the cops into a rear corridor but he couldn’t get the dead-bolt lock to slide. He rounded up Blake and his hirsute friend who had promised money and led the procession out into the office. One of the American men asked Fielden to take the women but Fielden shook his head. Fielden told the Americans to turn right at the sidewalk, right again at the first corner. “When you hit water you know you’re at the river.”

Hill was jumping up and down, trying to let Fielden know he was caught up in the crowd. One of the American girls grabbed Hill’s arm but he pried her fingers loose and joined Fielden, Blake, and his hairy monied friend in the front ranks. They ran to the Ford as the escapees sprinted. As the five men pulled away from the curb, the Mexican cops were already filtering back into the front office of the jail. The driver of a garbage truck pulled out in front of them. “Punch it!” Fielden yelled. “They’re trying to block us in.” “Calm down!” Hill yelled. “That guy’s just trying to turn around.” Hill had been in Mexico eight minutes, and the blurring rush of his amphetamine was really coming on. After what seemed like an eternity, they circled the plaza and reached the tollgate. Hill groaned and kept his foot away from the accelerator as the driver of a red station wagon chatted amiably with the customs toll-taker. Finally the station wagon moved on. Hill grinned at the Mexican official and handed him a quarter. Twelve cents would have sufficed.

As they crossed the bridge Fielden leaned forward and Blake started heaving incriminating evidence toward the river. Hill thought one of the guns bounced off the bridge, and Fielden looked back and saw one of the ski masks lying on the walkway. Everybody in the car was jabbering. Looming above the roof of the U.S. customs station was the neon sign of Texaco, and beyond that, Sears. “We’re home,” Hill was saying. “We’re clean, just stay calm, we’re gonna make it, we’re doing it, god damn, we’re home . . .”

The U.S. customs inspector was an old man. “Are you all American citizens?” he asked routinely. “Did you bring anything back from Mexico?”

When his editor called, Dallas Times Herald reporter Robert Montemayor was dressed to play tennis. A Texas Tech graduate and a cousin of the late Fred Carrasco’s trusted attorney Ruben Montemayor, Robert joined the Herald staff in hopes of specializing in reporting Mexican-American news. Tennis could wait. After nine months, Montemayor finally had a South Texas assignment.

On Friday, March 12, at the Maverick County jail, Montemayor talked to a Piedras Negras escapee detained on an outstanding U.S. warrant. The man sent Montemayor to the motel room of one of five escapees who’d been arrested in Eagle Pass and then released. They talked for two hours at the motel, and after midnight the escapee urgently requested a ride out of Eagle Pass for himself and his wife. He told Montemayor that Maverick County officers had warned that federales were in town looking for escapees. On Saturday Montemayor interviewed the comandante of the jail, then picked up his photographer and passengers and headed north. On the road Montemayor pressed the escapee for information about the breakout team. “They’ll be reading your newspaper,” the escapee finally hinted. In San Antonio Montemayor gave the escapee his Dallas phone number and reminded him, “You owe me a favor.”

Montemayor’s indebted passenger forwarded the reporter’s phone number to Blake, who was staying at a Dallas Rodeway Inn only one block from the Mexican consulate. On Sunday, March 14, Blake called Montemayor and said he was sitting beside the two men who had pulled off the Piedras Negras jailbreak. He answered a few of Montemayor’s questions but did not name Fielden or Hill, then said he had to turn himself over to federal marshals and would get back in touch in three or four days. Sterling Davis came to the motel happily shaking hands. Davis said there might be some movie money in this; one of his patients would draft an outline. Enthused, Blake mentioned that he’d been thinking about feeding some information to a Times Herald reporter. Sterling Davis was aghast. He pointed out that he was still on probation from the fraud conviction. Moviemakers fictionalized. Newspaper reporters named names.

Billy Blackwell took his $500 and went back to mowing lawns. Hill refitted his van with carpet, Naugahyde upholstery with a Lone Star flag motif, and a decorative American flag on the rear panel. Fielden, aware that Maverick County officers had found his sawed-off shotgun and the Mexican M-1 in weeds ten feet from the river, and suspicious of Davis’ Hollywood negotiations, told his story to his Dallas lawyer, Ernie Kuehne. Blake had served 14 months of his three-year U.S. sentence on the Arizona pot conviction. Since then he had served 23 months behind Mexican bars. Surely the federal authorities would agree that was punishment enough. When Blake turned himself over to the marshals, he confidently expected to be interrogated and freed after a few days. Instead the marshals charged him with parole violation and remanded him to the federal reformatory at El Reno, Oklahoma.

Robert Montemayor still did not know the name of the escapee who had called him. The escapee he’d driven to San Antonio came by for some clippings one day and asked Montemayor if Sterling had called him. Sterling? The Mexicans had first identified the escapee Blake Davis as Sterling Blake. Montemayor ran a check of area prisons and located Blake in the Dallas County jail, but it was a week before he was able to reach Blake at El Reno. Blake detailed his experiences by phone, then referred the reporter to his father for more information. At first Sterling Davis denied any knowledge of the matter. But twice during April, Davis granted Montemayor interviews in his office.

Montemayor noted that the doctor’s 1951 University of Mexico diploma was written in English. “I’m smiling at you, Robert,” Davis told the young reporter. “You’ll never know if a word of this is true.” Davis claimed he had spent $70,000 trying to free his son from Mexican prison. Montemayor applied a pencil to the doctor’s figures and observed they totaled only $40,000. By now Times Herald investigative reporter Hugh Aynesworth was working with Montemayor on the jailbreak story. Up to this point Davis had not revealed Fielden’s name, but two days before the article was to appear, he referred Montemayor to Kuehne, who in turn gave the reporters his client’s name. Aynesworth, who has a huge list of sources, quickly gathered information on Fielden, and when he told Kuehne the story was about to go to press, the lawyer called his client and said it looked like now was the time to talk.

Mike Hill was flabbergasted when he saw the copyrighted, joint byline story in the May 9 Times Herald. Hill had scarcely kept his role in the jailbreak secret; among friends he talked of little else. But glaring from the front page of the Sunday paper was a photograph of Fielden under the headline: DALLAS MAN EXECUTED JAIL BREAKOUT. Fielden was described in the lead paragraph as “a former Marine sergeant turned soldier of fortune.” In the story Fielden, apparently caught up in the drama of his own role, referred to Hill as “the backup man” and called Billy “a west Dallas punk.”

The next day Hill decided to share the spotlight; he appeared on the Channel 4 evening news wearing a ski mask and wielding a shotgun. In colorful detail he described the experience of standing down the Mexican guards. Sterling Davis confirmed his role in the break to UPI and consented to an interview by Montemayor and two television reporters. But the media party did not last long. The same Monday Hill appeared on TV, U.S. customs officials were in Kuehne’s office looking for Fielden. The next night at a north Dallas singles bar called the Number Three Lift, Kuehne and Fielden charted a course of action. They would cooperate fully, cop the best possible plea, and peddle the story for all it was worth. On Thursday, May 13, Fielden was charged with illegal exportation of the sawed-off shotgun and released on bond. Hill, who was not part of the bargain and had not been consulted about it, underwent the same process the next day. The following Tuesday, Fielden, Hill, the elder Davis, and Cooter were summoned before the federal grand jury in San Antonio.

The Piedras Negras jailbreak was flaring into an international incident. Mexican officials called Fielden and Hill common criminals and decried their heroes’ reception by the American press. The Mexican government initiated extradition proceedings against the American escapees. Wary of more American raids, penal authorities busily transferred prisoners and tightened security at all Mexican jails. In the past, U.S. embassy and consular officials had fielded allegations of Mexican abuse of American prisoners. Now the issue graduated from their hands. Out of Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s mid-June negotiations with Mexican President Luis Echeverría came proposals for a U.S.-Mexico prisoner exchange. In late June Gerald Ford signed a military assistance bill Congress had amended to commit the force and authority of the presidency to the investigation of prisoner abuse. Kissinger would submit a personal report to Congress; Ford would negotiate directly with the Mexican president.

To Mike Hill it seemed the world was spinning on his axis. Heads of state were probably talking about him. Yet Hill was broke again, and he was in the worst trouble of his life. One June night at White Rock Lake Fielden told Hill that he’d already cut his deal; it was every man for himself. Hill had been told by his lawyer to keep his mouth shut, but everybody else was talking. Once again Hill likened his predicament to scenes from his favorite movies. The Getaway. The Missouri Breaks. Paranoia overwhelmed him. Maybe he was an unwitting pawn on a huge conspiratorial chessboard. He was absolutely certain his old comrades were dealing him out of the movie game. Hill fired his lawyer and consented to an interview by Dan Rather. Sixty Minutes wouldn’t talk to him in Dallas; Hill had to go to Eagle Pass, where he nervously answered Rather’s questions with his back to the Rio Grande and Piedras Negras. Hill summoned a press conference the morning of June 28. He told reporters that he deserved equal blame or credit for the break, then he hitched a ride toward his arraignment in Del Rio, where he intended to plead not guilty.

In San Antonio that night Hill told me there would have been wholesale changes if he had commanded the Piedras Negras operation. “Namely, I wouldn’t have used Chubby,” Hill said of his former partner. Examining his motives, Hill said, “I’ve got a whole lot of potential. I can make a lot of money. Five thousand dollars don’t turn me on enough to make me wanta go die for it. I can make five thousand dollars in a little while, just working, doing what I do. I don’t know why I did it. But in the end I don’t think the money had anything to do with it. I’ll say this: if I ran for president I know seventeen people who’d vote for me.”

In Del Rio the federal indictments rained down. The original indictments against Fielden and Hill were superseded by a new four-count bill that named Hill on all counts, Sterling Davis on three, Billy Blackwell on two. Mentioned on three counts but indicted only for conspiracy, Fielden copped his plea. When Hill arrived in Del Rio he was looking at a maximum sentence of two years; when he left he was looking at as many as 22. Hill bitterly contended he was being prosecuted under pressure from the Mexican government. “If we’d killed anybody, the Americans would have taken us right back across that border, and I wouldn’t have blamed them a bit. We don’t have the right to go over there and kill anybody. I’d feel the same way if they’d come over and done something like that, if they’d killed anybody. But it was a peaceful kind of deal and the Mexicans don’t have any right to be mad, because nobody got hurt. They oughta be thankful for what they’ve got. That’s the main mistake people make; they ain’t never thankful for what they got left. They just cuss everybody for what happened to them. They don’t think about how bad it could have been.”

In Dallas Hill delivered Blackwell to U.S. marshals on June 30, then learned the judge in Del Rio wanted a $25,000 cash bond. Billy was in jail three days before the bond was reduced. When we talked over supper one night, Hill glumly said he had twenty cents to his name. “I’m not working because I can’t keep my mind on it,” he said. “And the way things are going, it looks like I oughta take a little vacation. It may be a long time before I get another chance.”

Ernie Kuehne is hopeful that Fielden will serve no more than a year. Endeavors to capitalize on Fielden’s exploit had proved taxing but fruitful. Austin public relations executive Neal Spelce listened to Fielden’s story and told Kuehne he believed they’d been scooped fictionally by the Charles Bronson movie Breakout. Fielden made a couple of promotional trips to Los Angeles and finally sold his story rights to Mustang Productions, a company owned in part by former Dallas City Councilman Charles Terrell. Kuehne said the deal might run well into six figures; of course, given the uncertainties of the movie business, it might amount to very little. On the advice of Kuehne, who dislikes Dan Rather, Fielden declined a Sixty Minutes interview, but after the plea was copped in Del Rio, he went public with a new image. He bought a new suit and had his hair styled. Kuehne portrayed his client as a figure larger than life, a patriotic veteran who, except for one wild act of valor, had a clean criminal record.

“Let him shoot his best shot,” Fielden said of Hill’s erratic efforts to crowd into the limelight. Asked for a personal reading of his former partner in arms, Fielden told me, “I wouldn’t go out partying with him, drinking or anything. I’m not saying I’m better than anybody else, but we’re coming from two different places. I like to feel I have a little class. I basically hired the man to do a job. He did his job, and he was paid for it.”

Fielden delved into his motives at the time of the break. “No one should be treated the way those prisoners were being treated. But the number one reason was the money. If somebody had said, ‘Well, I can’t give you any money, but would you please do it,’ I would have said, ‘Up your ass.’

“I really didn’t think I was doing anything wrong,” he continued. “If I’d known, going in, that I was going to be breaking the laws of this country—Mexico I didn’t care about—I wouldn’t have done it. But since I found out that I did break the law, I’ll have to pay for it. That’s the American way, isn’t it?”

But surely Fielden understood that even American prisons were no picnic ground?

“Now I won’t go in liking it,” Fielden said. “But the last thing I want is to owe this country anything. This country’s been good to me. If I owe it a year or two or five out of my life, well, I can’t run away. I’d be losing too much.”

Mike Hill was convinced that Fielden’s view of Hill as a hireling rather than a partner was costing Hill money. Had Blake’s electric-haired friend kept his promise to reward his rescuers? Had the other prisoners shown their gratitude to the man the Times Herald had portrayed as the leader of the jailbreak? If so, none of the money had found its way to Hill.

Billy Blackwell mowed his lawns in a daze, wide-eyed with fright. In El Reno, Blake Davis talked to nobody and hoped for an early release on parole. The world of Sterling Davis had been crumbling for some time. On May 12 he was forced to withdraw his application for a state psychologist’s license. On July 9 the Mexican consul in Dallas, Javier Escobar, announced that the National University in Mexico City categorically denied ever having granted Sterling Davis a degree. On July 12 Judge Sarah T. Hughes scheduled a hearing to discuss revocation of the discredited doctor’s probation.

Subpoenaed as a possible witness but unaccompanied by Kuehne, Fielden sat on the rear bench of Hughes’ courtroom in a new suit. “This pretrial release program is all right,” he said companionably. “They’ll send you to trade school if you wanta go. They keep trying to get me a job, and I tell them, man, I’ve got a job.” A job promoting Don Fielden. Hugh Aynesworth, whom Fielden considers “an OK dude,” shook his hand and took a seat beside him. Hill came in wearing a cowboy hat, accompanied by an attorney who wore a cowboy hat. Then Sterling Davis entered the courtroom, walking slowly and carefully, a gaunt but broad-shouldered figure in a gray suit.

Judge Hughes said they would not discuss particulars of the Piedras Negras jailbreak, since Davis was charged in connection with that in another federal court. However, U.S. attorneys charged that in November 1975 and February 1976 Davis violated terms of his probation by leaving the country without permission. They claimed that at the time Davis was telling Robert Montemayor and two television reporters he had spent $70,000 trying to free his son, he had paid only $225 of his $16,000 restitution obligations and retired only $200 of his $10,000 fine.

On the stand Davis said one of the violations was the result of a misunderstanding on his part. To him Eagle Pass and Piedras Negras were one and the same. On one occasion he asked his probation officer if he could go to Eagle Pass to take Thanksgiving leftovers to his son. He attributed the $70,000 figure to a misunderstanding by Montemayor: he had told the young reporter about a woman in California who claimed to have squandered $70,000 trying to free her son, but he never claimed that himself. (“The conversations are on tape,” Aynesworth said later.) When he quoted that figure to the television reporters, he was trying to enhance his movie negotiations; indeed, he had warned the reporters that he would not be telling the truth. In order to meet the monetary demands of his probation, Davis said that in the past few weeks he had borrowed $3000 on his life insurance policy, $2000 from his son, $1000 from his mother-in-law. After the trial in Del Rio the $2500 he had used to post bond would be forwarded. He was prepared to sign over his movie contract rights . . .

“What is this movie?” Judge Hughes interrupted. “I want to know more about it.”

“When all this came out in the newspapers,” Davis explained in a soft, deep voice, “people descended from everywhere. Movie and book people. Most were, pardon the expression, fly-by-nighters. But Warner Brothers advanced me a thousand dollars on a movie contract. The Warner Brothers people were here in town last week. They’re supposed to start shooting in September.”

Davis continued that he was not a rich man. A thousand-dollar advance is not much assurance in the movie business, and Davis’ attorney conceded the letter agreement was rather loosely written. After the frog farm trial he had trouble finding work. Just when he was getting on his feet, he had to hire a full-time nurse for his invalid mother-in-law.

“How much did you pay the nurse?” the U.S. attorney asked.

“Eleven dollars a day,” Davis replied.

“How did you afford that?”

Davis started to answer, then winced and closed his eyes. If the long moment of silence was a con, it was a brilliant performance. “I was working then,” Davis finally said, “teaching. Sometimes the students asked for counseling.”

Davis’ attorney reminded the court of the doctor’s heart and diabetic conditions and then played his trump cards. The attorney entered as evidence two letters which indicated the $5000 that financed the breakout was raised by friends of Blake and forwarded to the doctor by a Tucson attorney.

Judge Hughes recessed the hearing pending disposition of the September 21 trial in Del Rio, where the elder Davis, Hill, and Blackwell would face the charges of international gunrunning. Fielden’s sentencing was set the same day in the same courtroom. Kuehne insisted that the terms of Fielden’s deal did not include turning state’s evidence, but by pleading guilty Fielden has waived his Fifth Amendment rights. If subpoenaed, Fielden would have no choice but to testify against his former comrades.

Mike Hill cut Fielden a baleful look as he left the courtroom. As Sterling Davis moved slowly toward the elevators, he nodded to reporters and Fielden. The smile on his face was inscrutably kind. In the hallway Fielden stood talking to the U.S. customs agents who had conducted the Piedras Negras investigation. For a man bound for the penitentiary, Fielden looked remarkably happy. His rounded cheeks seemed on the verge of explosive laughter. As a part of some publicity hustle, he was going to Scotland to dive in search of the Loch Ness monster. Don Fielden. Soldier of Hollywood fortune.

Four hundred and twenty-five miles away the Rio Grande was raging. Rain had been falling at Eagle Pass and Piedras Negras for nearly two weeks: maddening rain, ten or fifteen brief showers a day. Knowledgeable residents of Eagle Pass claimed the American escapees had picked the worst spot to swim the river. As the river sweeps around the International Bridge abutments it deepens and forms strong undertows. When the American escapees splashed into the water the morning of March 11 the Rio Grande was running shallow. Four months later the flooding river churned violently and frothed with heavy debris; only the strongest swimmer could have stayed alive in that current beneath the bridge.

Across the river, the Piedras Negras municipal jail was a bristling fortress braced for attack. More armed guards, more heavy steel bars. It was no place for gringos to go sightseeing. A khaki-uniformed officer gripped his carbine sling and squinted malevolently at three American visitors who seemed excessively interested in the barred door and corridor back to the cells. When the suspicious-looking Americans hurriedly drove away, three guards ran outside to record the license number. Too late, the Mexicans had learned to be careful. In the coffin-like cells of Piedras Negras jail, two new American prisoners waited for someone to come rescue them.

- More About:

- Mexico

- Longreads

- Crime

- Eagle Pass

- Dallas