On April 19, 1994, the day that seventeen-year-old Napoleon Beazley committed cold-blooded murder, the high school senior came home from track practice, showered, and changed into a fresh pair of blue jeans. At that moment, just before he loaded his Haskell .45-caliber semi-automatic pistol and tucked it into his pants, the future held more promise for Napoleon than it had for generations of Beazleys before him, who had made a modest living raising peanuts and cotton near the East Texas town of Grapeland. Napoleon was the president of his senior class and a star athlete, a bright teenager with a loose-limbed confidence and a dazzling smile who had just been voted runner-up for the title of Mr. Grapeland High School. He didn’t drink; he didn’t smoke; he went to church on Sunday. He was an honor student and hoped to attend Stanford Law School someday. But for a light-skinned black teenager mocked by his black peers for acting “too white,” success was not always a blessing. Ambition kindled resentment on the rutted roads south of Chestnut Street, where sagging frame houses have gone to seed and young men idle under shade trees and stray dogs root around for bones. Here, the pistol lent him the hard-edged, cocksure certainty that no scholarship or touchdown could ever provide.

That night, Napoleon left Grapeland with two small-time hoods, brothers Cedrick and Donald “Fig” Coleman. What happened next would prove to be unfathomable to those people in Grapeland, white and black, who had known Napoleon throughout his short but promising life. He and the Coleman brothers headed first for Corsicana, then for Tyler, an hour’s drive north of Grapeland, looking for a vehicle to carjack. Around eleven o’clock they caught sight of a cream-colored Mercedes-Benz, which they began to tail through a residential neighborhood of large, cantilevered houses and manicured lawns. Inside the Mercedes, Bobbie Luttig sensed that she and her husband of 41 years, independent oilman John Luttig, were being followed.

As John Luttig drove into their garage, Napoleon darted up the Luttigs’ winding driveway, his pistol drawn. Fig Coleman strode behind him, holding a sawed-off shotgun, while Cedrick waited in the car. No doubt John Luttig would have peacefully handed over the keys to his Mercedes, but he never had the chance. As he stepped out of the car, Bobbie heard him utter one word—”No!”—and then saw the flash of a gun muzzle. John Luttig fell to his knees, struck by a bullet that had grazed his head. Napoleon then fired at Bobbie. Though the shot missed its mark, she sank, terror-stricken, to the garage floor and played dead, her face pressed against the oil-stained cement. Her husband was still alive, kneeling beside the car in shock. Napoleon leaned over the bleeding man and pulled the trigger again. Bobbie kept still, her eyes shut, as her husband’s blood coursed down the driveway. Only after the Mercedes skidded away did she dare move, racing to a neighbor’s house and telling the 911 dispatcher, “My husband has been shot. Please hurry!”

“Carjackers Kill Tyler Civic Leader Luttig,” the headlines read the next day. “Friends Astounded By Brutal Act.” What set this crime apart was not its depravity, or its casual violence, or its utter senselessness but its power to stir deeply divided emotions—in Grapeland, in Tyler, even in the highest echelons of jurisprudence, all the way to the United States Supreme Court. Napoleon Beazley was not just any murderer, and John Luttig was not just any victim. Napoleon was a minor at the time of his crime, and his case inevitably raised the question of whether even a vicious killer can be too young to be sentenced to death. John Luttig was not only a prominent white citizen in Tyler but also the father of the Honorable J. Michael Luttig, a federal judge who sits on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit and is believed to be on President Bush’s short list for potential Supreme Court nominees. Judge Luttig asked that “those who committed this brutal crime receive the full punishment that the law provides.” A Smith County jury later sentenced Napoleon to death.

And yet in Texas, hardly known for its hesitation in administering the death penalty, Napoleon Beazley’s death sentence has given some unlikely people pause: As Napoleon’s first execution date neared last August, the hard-nosed state district judge who oversaw his 1995 trial asked the governor to commute his sentence to life in prison, citing the fact that Napoleon was seventeen at the time of the crime. The district attorney in Napoleon’s native Houston County petitioned the governor for leniency, citing his prior good character and lack of a criminal record. No less extraordinary, the U.S. Supreme Court deadlocked 3–3 over a stay of execution after three justices with personal ties to Judge Luttig, the victim’s son, recused themselves.

Last August the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals stayed Napoleon’s execution just four hours before the sentence was to be carried out. The court can grant a hearing—or allow his execution to proceed—at any time. In the days and weeks ahead, the court must weigh both the crime and its proper punishment and rule whether justice should be tempered with mercy, or whether Napoleon Beazley deserves to die.

Words seem trite in describing what follows when your husband is murdered in your presence, when your father is stripped from your life. The horror, the agony, the emptiness, the despair, the chaos, the confusion, the sense—perhaps temporary but perhaps not—that one’s life no longer has any purpose, the doubt, the hopelessness. There are no words that can possibly describe it, and all it entails.

Testimony of J. Michael Luttig

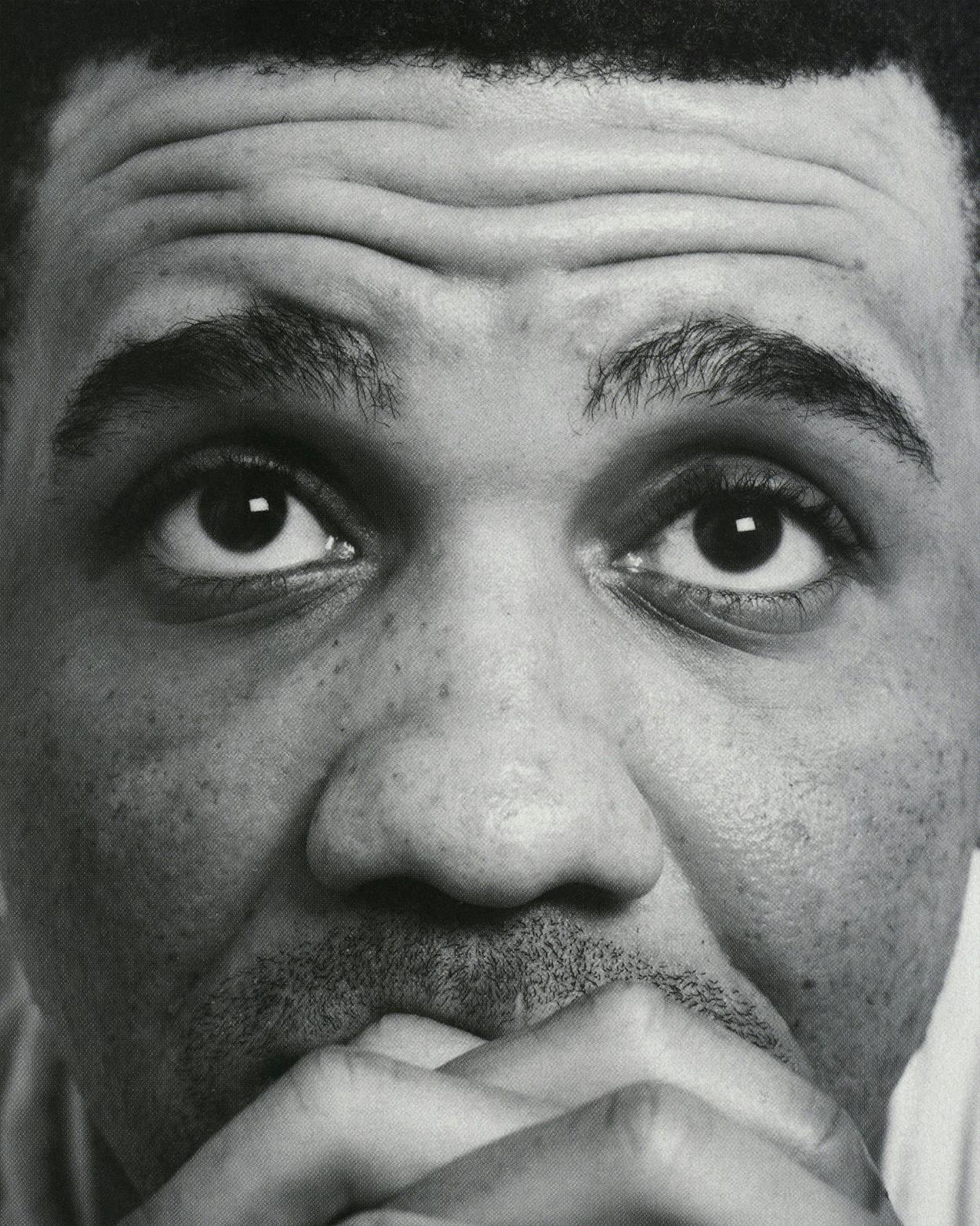

“Any explanation I give for why it happened would seem like a justification, and for me, there is no justification for what happened,” says Napoleon Beazley. He is seated behind a sheet of Plexiglas at the Terrell Unit in Livingston, the new home of death row. “I don’t blame my family; I don’t blame my friends; I don’t blame society. I don’t blame the judges, the lawyers, or the ‘white man.’ I don’t blame anybody for what happened but me.” Now 25, he has the articulate, precise delivery of the debate team standout he once was at Grapeland High, and if not for his white prison uniform, he could be equally convincing on the other side of the visitation booth as a young lawyer conferring with a client. His face has grown wan from lack of sunlight, and his eyebrows are raised in an expression of permanent surprise, as if he is amazed to find himself in such improbable surroundings. Even after eight years in prison, he seems an ill fit: He does not try to impart any false charm, or spin self-interested conspiracy theories about his case, or assign others blame. “I made choices, bad choices,” he says. “A lot of people grew up with the same opportunities and challenges I had, and they didn’t end up on death row.”

Long before Napoleon Beazley was classified by prison number 999141—before he ever fell in with the Coleman boys or felt the cool steel of a gun in his hand—he was the toast of Grapeland. Thirteen miles north of Crockett, Grapeland is a town of 1,451 people tucked away in rolling farmland, a lonely whistle-stop with one blinking yellow light, several mom-and-pop stores, and a farmer’s co-op where bags of seed lean against old tin sheds. Well-paying jobs are scarce, but the mood is upbeat: The Grapeland Messenger fills its pages with pictures of the Sandies’ football victories, washer-pitching contests, and Peanut Festival queens, and the hometown radio station, KBHT, plays Fats Domino as well as the local farm report. By sundown, the town’s business strip is deserted, the occasional Union Pacific freight train casting the only bright light for miles when it hurtles down the railroad tracks along Main Street, its high beam cutting through the darkness. North of Chestnut Street, the cars are newer, the streets wider, the yards greener. The large white houses with American flags fluttering out front suggest far more opportunity than the Quarters, the black side of town into which crack cocaine has crept, a place rattled by hip-hop’s percussive bass lines and the backfire of rusting brown Oldsmobiles that sputter down country roads.

Napoleon Beazley was raised in the Quarters, in a tidy brick house ringed by a hurricane fence next door to St. John’s Baptist Church, whose white clapboard walls shudder each Sunday with gospel hymns. Napoleon’s father, Ireland, works as a line supervisor at the local steel mill, and his mother, Rena, is the first black teller at Grapeland State Bank. The Beazleys are among the Quarters’ most prominent citizens: Ireland was Grapeland’s first black city councilman, and their daughter, Maria, attended Rice University, an anomaly for this blue-collar town. In the Quarters, where divorce and welfare dependency are the norm, Ireland and Rena have been married for thirty years and enjoy a lifestyle of relative prosperity. Upward mobility has exacted its price, however; in the Quarters they are viewed with equal parts admiration and jealousy. Over the years, some black residents have griped that the Beazleys were too standoffish, and white residents on the other side of town, though increasingly friendly, did not always greet them with open arms. “I went through the motions, and I performed,” Rena says of her time as Grapeland High’s first black cheerleader, following integration in 1968. “As far as being embraced and accepted by the other girls, I never felt that. It was lonely.”

Her yearning for a better life was born in a drafty frame house “under the hill,” the poorest part of the Quarters, where she grew up hungry alongside six brothers and sisters and whatever drifters her grandmother took in. Rena spent her summers working in the fields, hoeing peanuts until her hands were blistered, and she made do with one pair of shoes whose cracked soles let the rain in. Now, at 47, she is always stylishly turned out, her cinnamon hair done beauty-shop perfect, framing a warm but guarded smile. Outward appearances have always been important to her: In high school she had her cheerleading uniform dry-cleaned before every game, even though it meant skipping meals. She was fourteen and Ireland fifteen when they exchanged glances in the balcony of the old movie house. He was a running back, a sturdy farm boy with an easy manner and a strong sense of faith, and they married after graduation. The Beazleys wanted to give their children what they had lacked; Rena took a job at a Crockett department store when the children were little so she could buy them new clothes on discount. She starched and creased Napoleon’s jeans—he had one pair for each day of the week—and at Christmastime, she let him pick out shirts from the J. C. Penney catalog.

The middle child of the Beazley children—Maria is the oldest, Jamaal the youngest—Napoleon shares the same name as his great-grandfather, a circuit preacher. Eight years after Napoleon’s arrest, he is still remembered around town for his unfailing good manners. “He wasn’t one who had a chip on his shoulder,” says one white woman. “It was always ‘Yes, ma’am’ and ‘No, ma’am’ with Napoleon.” At school he had a nearly perfect attendance record; while other students slumped disinterestedly in their chairs, he sat in the front row, making astute observations in a soft, measured voice. And though fistfights were routine among other boys, no one can remember Napoleon so much as raising his voice. “He was the peacemaker,” says classmate Casey Vickers, now a crewman for a gas company. “If the guys were calling each other names on the football field, he’d smile and defuse the situation.” Off the field, he was a loyal friend, as when he helped Casey win back his high school sweetheart, now his wife, by ghostwriting poetry that Casey slipped into her locker.

Casey was part of the close-knit group of friends Napoleon had come of age with, all of whom were white. As kids, they played tee ball and Little League together; later on, they lifted weights and chased girls and scored touchdowns together, always certain of one another’s loyalties. “In our town it was unusual for us to be running around together, but Napoleon was always just one of the guys,” says classmate T. C. Howard, now an emergency medical technician in Crockett. “He blended in.” Still, their friendships weren’t easy. “Once school was over, it was understood that you went your separate ways—you didn’t hang out with your white friends at night or on the weekends,” says Maria. “Napoleon crossed that line.”

“People stuck with their own for the most part,” says classmate Jimmy Moffett, now a draftsman for a steel company in Dallas. “Napoleon broke the rules, and he caught a lot of flak for that. Black guys talked down to him. They put a lot of pressure on him to be tougher, to be bold.” Moffett sighs heavily, as if the weight of the past eight years were bearing down on him. “I wish Napoleon could’ve ignored all that. He didn’t have to prove anything to us.”

You sit at Thanksgiving dinner, the dinner that your wife has prepared that at all other times would be a feast. You sit there with your mother and your wife and your daughter, and no one says a word, not a single word. There is only one thought in all four of your minds and that is that your dad’s not there, and he never will be again. You make small talk. You pretend like nothing has happened and that there is nothing else on your mind. You tell your wife that the meal tastes great when you can hardly keep it down, and then you get up and you go do the dishes so that they won’t see you crying.

Testimony of J. Michael Luttig

What many of Napoleon’s white friends did not understand was just how tricky it was to straddle the two worlds divided by Chestnut Street. On the white side of town, his friends’ parents embraced him out of genuine affection and, perhaps in small part, to assuage a nagging sense of guilt. They had grown up under Jim Crow and the court-mandated integration of Grapeland High—a time so fractious that one of Napoleon’s cousins, Angie Dickson, claimed that she had been denied the title of 1969 valedictorian because of her race. Napoleon represented a more untroubled future, and the parents of his white friends welcomed him, saying he should think of their home as his own. He was, some of these parents later said, like a son to them. But in the Quarters his peers nicknamed him White Boy. “Among the people we grew up with, Napoleon wasn’t liked,” says Maria. “There was a certain way you were supposed to be, and he wasn’t that way. He was light-skinned. He spoke proper English. He stood out. We’d both been taught to carry ourselves differently, and kids took that to mean we were stuck-up. Other kids would say to him, ‘You’re white’ or ‘You think you’re white.’ ”

“I don’t think Napoleon saw color,” said Casey Vickers. “Other people did.” One time, when Napoleon was seven years old, he was turned away from a white classmate’s birthday party: “Y’all aren’t welcome here,” a man had informed his father as Napoleon stood, puzzled, holding the unwanted birthday present. But it was the ridicule of black kids, Napoleon emphasizes, that stung. “I’ve felt more racism from blacks than I could ever experience from whites,” he wrote me in a letter from prison. “Because some of my friends were white, I was ridiculed. Because I dated white girls, I was ridiculed. Not by white people, black people.” Pulled between two worlds—he would never completely belong on either side of Chestnut Street—his own identity would become increasingly fractured. “I wanted to be accepted, so I did what I thought was necessary to fit in,” he wrote. “I was, quite frankly, a chameleon, an actor. I played roles and changed colors to fit the scene and the script.” Most of all, he wrote, “I wanted to be black.”

No one, in Napoleon’s eyes, was blacker than his cousin Timmy, a Grapeland Sandies football player five years his senior who moved, poor and without prospects, to Houston after graduation. His cousin came home driving a low-slung white Cadillac, his fingers glittering with diamonds and gold. He was a crack-cocaine dealer, and although he would be arrested in 1998 in a Drug Enforcement Administration sting, that was far too late to keep Napoleon out of trouble. Back then, even after Rena had barred her nephew from the house, he managed to slip Napoleon a few rocks of crack and schooled him in the ways of the street. To a thirteen-year-old, the appeal was powerful. “When my cousin came home, he was accepted, admired, respected,” Napoleon wrote. “No one questioned his blackness.” Napoleon began dealing crack, though he sold it seldom enough that word never got back to his family or friends. As a track star, he had the perfect cover: He jogged at night with $20 rocks in his pockets, slowing down when he spotted a likely buyer. He never made much, he says, because money was not the allure: “My crack dealing was never serious; keeping the image was.” Dealing drugs garnered him the approval he hungered for. “When I dealt crack, I was accepted by the blacks everyone considered hip,” he wrote. “Sad, but true.”

Crack would take him to the deepest part of the Quarters, to the squalor under the hill that Rena had tried so hard to shield him from, a world so different from the one he was raised in, he says, that he often felt like a “voyeur.” Under the hill, a fellow crack dealer named Cedrick Coleman would take Napoleon under his wing. Three years older than Napoleon but only one grade ahead, Cedrick was the handsome, smooth-talking star running back of the Sandies, named all-state his junior year and a blue-chip player in Dave Campbell’s Texas Football. He was as close to a hero as Napoleon had ever known. As the Sandies’ second-string running back, Napoleon learned to emulate his moves—off the field as well as on. “Cedrick had all the answers,” he says.

By the summer before his senior year, Napoleon was drifting away from his friends north of Chestnut Street and growing closer to Cedrick, whose hotheaded little brother, Fig, was always underfoot. The Colemans’ world was one of capricious violence, in which cousins were gunned down, fistfights were common, and the police were known to come calling. Napoleon also began dealing crack with Cedrick.

Ireland and Rena grew concerned that summer, having learned from a friend that Napoleon was involved with drugs. They had their son tested for drugs twice, but the results were negative. “You’re wasting your money,” Napoleon told them with a good-natured grin. “You don’t need to worry.” That fall he seemed too busy to get into mischief: He earned straight A’s, played football, worked on his uncle’s farm, and lifted weights for two grueling hours a day. Still, his friends noticed that he was changing. “Napoleon was evolving into a different person,” says Jimmy Moffett. “He was trying to be something he wasn’t.” Privately, the sixteen-year-old was overwhelmed: A girl he had dated briefly that summer had told him she was pregnant, making the football scholarship he had pursued since junior high no longer an option. He would have to support the child. “All my hopes, dreams, and aspirations were in the progress of a ball,” he wrote to me. “I gave that up . . . I was trying to be a man.” He knew a military salary would allow him to provide for the baby, so he joined the Marines, deferring his induction until after graduation. His parents initially made their disapproval known, but he assured them he would attend college on the GI Bill and apply to Stanford Law. When the baby was born, in March 1994, the spring of his senior year, Napoleon learned he was not the father. He had been duped. “I was devastated,” he says.

Cedrick Coleman was back in Grapeland by then, having dropped out of Navarro College in Corsicana—not a Big Ten school, as he had hoped; his grades were too bad—and after an injury in the fall of 1993, he was no longer the football star he had once been. He and Napoleon grew closer, each deflated by ruined dreams. Napoleon bought a gun that outshone Cedrick’s .25-caliber pistol and kept it tucked in his jeans. The two friends were playing video games one afternoon when Cedrick mentioned a drug dealer he knew in Palestine who had carjacked a Mercedes and proposed that they do the same. “You down with that?” he asked. Napoleon—the president of his senior class, honor student, top athlete—answered him with little hesitation. “I’m down with that,” he replied. And so on April 19, 1994, Napoleon, Cedrick, and Fig would drive to Tyler with loaded guns.

[When I told my mother that the FBI had arrested three people, she] collapsed on the floor of the kitchen. It was a writhing kind of pain I had never seen in my life. I went down on my knees to comfort her, and she cried. . . . I thought my mother was having either a stroke or an attack, but all she was doing was coming to grips for the first time with the fact that this was really done for a car, for a ten-year-old car.

Testimony of J. Michael Luttig

Jimmy Moffett had a bad feeling the next morning in first-period government class when he saw that Napoleon’s chair was empty. Since kindergarten, he had never known Napoleon to miss a day of school. Jimmy was taken aback later that day when he caught sight of his friend, who seemed not of this world: Napoleon had dark circles beneath his eyes and his expression was grim, his shoulders slumped in resignation. He did not flash his usual easy grin. When Jimmy asked what was wrong, Napoleon stared through him. Napoleon unburdened himself two days later as they walked to the gym to have their yearbook pictures taken: Jimmy was Mr. Grapeland High School, Napoleon the runner-up. Napoleon lowered his voice until it was almost inaudible. He and the Colemans had stolen a car, he said morosely. He had shot the driver and shot at the driver’s wife. It had happened so fast, he said. It had all been a mistake. Jimmy found this admission so disturbing that, as an adult, he would be married for three years before he could speak of it to his wife. “I couldn’t imagine Napoleon doing anything that violent,” he says. “I asked him, ‘Why did you take a loaded gun? Why did you have to shoot the man?’ and he had no answer.” The crime had been for naught: Napoleon and Fig drove the Mercedes only a few blocks before it got a flat tire, and they were forced to abandon it. Cedrick, who had followed them, drove them back to Grapeland. “It would’ve been better if we’d gotten the car,” Napoleon told Jimmy.

A massive FBI manhunt was already under way: Carjacking is a federal crime that falls under the FBI’s jurisdiction, and this particular carjacking’s link to the father of a federal judge only intensified the scrutiny. Investigators had little to go on during the 47 days it took to crack the case, but loose lips would help them. Fig soon blurted out the details of the murder to his girlfriend and his stepfather, and though Jimmy kept Napoleon’s confession in confidence until later questioned by FBI investigators, teenagers in the Quarters began to whisper. Napoleon ate and slept little that spring, but he tried to keep up appearances, pouring himself into fanatical workouts that left him spent and weak-kneed. The strain showed: In photos from that time, he is often pictured standing off to the side, smiling weakly. To the Beazleys, he seemed subdued, but Rena took his changed behavior—he went to church on his own, he stopped teasing his little brother, Jamaal, he stuck close to home—as signs of maturity. “I thought he was getting his priorities straight before graduation,” she says. “I didn’t think to dig deeper.” Her son had a private moment of reckoning that May at the state track meet in Austin, moments before running in the four-hundred-meter relay. As he crouched in the blocks, listening to the cheers of the crowd, he was overcome with a sense of regret so piercing that it felt like physical pain. This was what his future should have been.

Two weeks after Napoleon graduated from high school with honors, one week before he was set to leave for the Marines, a Crime Stoppers tip—settling an old score, perhaps—sent FBI agents in Tyler hurrying south to Grapeland. The Colemans were arrested after a lengthy interrogation that night, June 6, and near midnight, Napoleon was read his rights at his grandmother’s house as his father looked on in disbelief. Ireland followed the convoy of police cruisers—one holding Napoleon, another Cedrick, another Fig—down the dark, two-lane country roads that led north to Tyler, as incredulity gave way to a profound sense of dread. Only later did he learn that his son faced capital murder charges. “There was a moment where I could’ve talked to Napoleon, but I was so devastated, I couldn’t find the words,” says Ireland. “The FBI had shown me the Colemans’ statements, and that blew my mind. They said my son killed a man. Even if he’s proven guilty a hundred times, he’s still my son.” As the sun came up over Tyler that morning, Ireland sat in his black pick-up truck and bowed his head in prayer, weeping in the first light of day. He composed himself long enough to consult with a local defense attorney before Napoleon’s arraignment that morning. “He said he couldn’t represent my son, because he knew the Luttigs,” recalls Ireland. “Then he said he had to prepare me—that my son would be killed for this.”

Bail was set at $1 million. In a city unacquainted with carjackings and businessmen being gunned down in their driveways, the brutality of John Luttig’s murder had sparked outrage. “This was a predatory hunt down of the victims in a totally random manner, and that was one reason the crime was so shocking to the community,” says Smith County criminal district attorney Jack Skeen, Jr. Emotions ran so high in the courtroom at his son’s arraignment, Ireland says, “The feeling I got was that if someone had hollered, ‘Let’s get a rope,’ they would have hung him from the highest tree.”

Napoleon was taken to the Smith County jail as word traveled through Grapeland that he had been arrested for murder. “It was like a knife through the heart of this town,” says Sandra Kerby, the editor of the Grapeland Messenger. “There was shock, sadness, a sense of disbelief.” Many assumed that the Colemans had pinned the murder on Napoleon or that they had goaded him into pulling the trigger. His arrest, even to his closest friends, was mystifying—and set off what would be years of pained examination, not just of Napoleon but of themselves. “There may have been times when he was asking us for help, for guidance, and we were so comfortable in our own lives that we didn’t notice,” says T. C. Howard. “Was there something we could’ve done? Something we could’ve seen? We looked hard. When we’d all get together, we’d try to have a good time, but the conversation always came back to Napoleon. We all felt guilty.”

That day, Casey Vickers received a collect call from the Smith County jail. When the phone rang, Casey was sitting in his parents’ living room, his hands dirty from loading feed, his face hot with tears. He was overcome with emotion when he heard the voice on the other end of the line, but he said only one word: “Why?” Napoleon would never answer him. Napoleon’s two separate worlds had collided, leaving him at a loss for words. Napoleon cried into the receiver until their time ran out. Before he hung up he told Casey, “The world is yours.”

Then the day arrives, and the trial begins, and you listen to your mom talk about how she crawled on the floor in the filth and the grease of the garage of her home to keep from being murdered by the people who just murdered her husband. . . . You listen to the pain, and you watch her face. . . . There are no words for it. You know, the idea of this elegant woman, my mother, crawling on the garage floor to keep from being murdered, that’s something that you have to live with for the rest of your life.

Testimony of J. Michael Luttig

For two weeks in the spring of 1995, a Smith County jury weighed whether Napoleon Beazley should live or die. Had Napoleon stood trial in federal court, he would not have faced execution, for federal courts cannot impose a death sentence on a minor. Federal law is rooted in the idea that adolescents, by their nature, are less mature than adults and that the impulsiveness and poor judgment of youth are mitigating factors that should exempt teenagers from the ultimate punishment. Texas law holds that seventeen-year-olds who are capable of committing “adult crimes” deserve adult punishments. Age was not made an issue at the trial by Napoleon’s defense attorney, and any testimony about his past good character was overshadowed by the sickening details of his crime. The well-mannered Grapeland honors student had, according to Fig Coleman’s testimony, told him to “shoot the bitch” as Bobbie Luttig lay terrorized on the garage floor that April night. “I was contemplating my own death, which I thought was imminent,” John Luttig’s widow told the jury, her pale face lined with grief and private sorrow. “I was wondering what the bullet would feel like as it went through my back. I was wondering what it would feel like to die.”

The all-white jury (both the prosecution and the defense had rejected potential black jurors) found Napoleon guilty of capital murder. The staggering catalog of evidence—the fingerprints on the Mercedes, the shell casings, Fig Coleman’s eyewitness testimony, the confession to Jimmy Moffett—all pointed squarely at Napoleon, who did not enter a plea of innocent or guilty and remained silent about his crime. To win a death sentence in the punishment phase of the trial, the prosecutors had to prove that Napoleon was likely to commit future acts of violence. Their argument relied not only on his past crack dealing but also on the testimony of the Colemans, who took the stand to make three damning assertions: Napoleon had boasted of wanting to kill someone, he was remorseless, and he had threatened to kill them if they talked of the crime. Two psychologists subsequently testified that Napoleon was a future danger to society, basing their assessments in large part on the Colemans’ accounts. But in sworn affidavits that the Colemans signed after receiving life sentences, they recanted their most damaging testimony, claiming they had lied as part of a deal with prosecutors to avoid the death penalty themselves. FBI investigators and even the Colemans’ own lawyers, however, signed affidavits denying their claims of deal making. District attorney Jack Skeen, Jr., also vehemently denies any deal. “This was a deliberate, preplanned, cold-blooded crime that showed a wanton disregard for human life,” he says. “The facts of the crime itself were sufficient to prove future dangerousness.”

What moved the jury more than any crime-scene photograph or 911 phone call ever could was the testimony of Judge J. Michael Luttig, whose eloquence on the stand gave jurors a glimpse of the anguish and profound loss that his father’s murder had wrought. A man of quiet intensity, he was ever-present, his brow furrowed in concentration as he listened to witnesses and viewed the evidence at hand. He took the stand on the last day of the punishment phase, and as he sat in the witness box, he searched for the words to capture a personal tragedy so shattering that it defied description. His father had been a man of great integrity and principle, he said, who was not only his hero but his best friend. “I worshiped the ground that he walked on,” he said to the jury. He told of picking out the clothes his father would be buried in. He told of how his mother trembled through the night from fear and bolted out of bed at the slightest noise. He told of hearing that the blood seeping from his father’s head had “sounded like running water.” He told of his sister’s horror at viewing their father’s body. He told of spending Christmas at his father’s graveside, smoothing the soil around the marker, “so it will be perfect in the way that he always wanted things for you. And then you sit there. You sit there for hours. Wait till the sun goes down, and it’s cold. You sit there until finally you can’t, and you get up and leave. And you say, ‘Merry Christmas.’ ”

The jury sentenced Napoleon Beazley to death after less than two hour’s deliberation. Though an unusual array of witnesses had come forward on his behalf—his high school principal, football coach, teachers, friends, and fellow church members—it was not enough to sway the jury. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals upheld his conviction on appeal, and after the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a lower court’s denial of habeas corpus relief, Napoleon’s execution date was set for August 15, 2001. State district judge Cynthia Stevens Kent, who had presided over his trial, subsequently voiced her concerns in a letter to Governor Rick Perry that Napoleon was too young to be executed. “It is my recommendation that due to his age at the time of the offense that you consider carefully and grant his request that his sentence be commuted from the death sentence to a sentence of life imprisonment,” she wrote. No less remarkable, Houston County district attorney Cindy Garner, who lives in Grapeland, wrote to the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles: “Based on my knowledge of Napoleon Beazley as a person, as well as my knowledge of the facts of his criminal offense, I would not have sought the death penalty had this case been filed in Houston County.” As Napoleon’s execution date neared, six of the sixteen members of the Board of Pardons and Paroles—which can recommend that the governor grant clemency—voted to commute his sentence to life. It was the board’s closest vote, apart from one case of likely innocence, in the past one hundred capital cases it had reviewed. Governor Perry could have granted a thirty-day reprieve, but he did not: “I am comfortable that my seventeen-year-old son knows the difference between right and wrong,” he later said. “And the law in the state of Texas says a seventeen-year-old has to take responsibility for his actions. My duty is to uphold the law.”

Last June Napoleon’s appellate attorneys, David L. Botsford and Walter Long, of Austin, asked the U.S. Supreme Court to hear Napoleon’s appeal and grant him a stay of execution. The attorneys presented several arguments, citing both Constitutional and international law; foremost among them was the claim that executing people who were under the age of eighteen at the time of their crime constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. As the case was weighed by the nation’s highest court, three justices with personal ties to Judge Luttig—Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and David Souter—recused themselves from deliberations. Their absence left the court in a deadlock—three for a stay, three against—resulting in a denial of the stay. In turn, Botsford and Long filed a last-minute petition with the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, raising numerous issues, among them Napoleon’s age at the time of the crime, racial bias on the all-white jury that convicted him, and the veracity of the Colemans’ testimony. On August 15 the Court of Criminal Appeals, in an unusual 6–3 decision, decided to stay Napoleon Beazley’s execution “pending further orders by this court.” The court did not specify which issues it would examine nor when it would make its decision regarding whether the execution should proceed.

Napoleon had already bid goodbye to Ireland and Rena and was sitting a few feet from the death chamber, writing his last statement, when prison chaplain Jim Brazzil came to tell him the news. Napoleon stopped writing and looked up at the chaplain, stunned. Brazzil asked him if he was all right. “Yes, I’m fine,” Napoleon said. “I just have to comprehend this. Give me a second.”

The first thing you come to grips with is dying, and afterwards there are only reasons to live.

Letter from Napoleon Beazley

The last time I saw Napoleon Beazley, it was a gray and blustery winter day outside the Terrell Unit. Since arriving at death row, Napoleon has had a perfect disciplinary record; by all accounts, he is a model prisoner who has spent his time imparting the life lessons he has learned to other inmates. “I’ve destroyed enough lives, so saving them is important,” he told me. “My self-redemption is important. The biggest apology I can give is to change and to show through my actions that I am a changed person.” He now spends his time in isolation, his movements limited to a six-by-ten-foot concrete cell with a slit of window, which provides a glimpse of sky above. That winter day, I stared at Napoleon through the Plexiglas that separated us and wondered at the true, innermost thoughts of a person who was, even to his closest friends, an enigma. He had committed an unconscionable crime, one for which he should pay dearly. Never again should he have the freedom to run through the grass in his bare feet, as he has longed to do, or to know the comfort of a moment outside these walls. But was death the appropriate punishment? “I’m biased,” he acknowledged. “I’m biased. But I do believe in forgiveness. I believe in rehabilitation. I believe that I can do some good while I’m still here.”

Eight years after the murder of John Luttig, Grapeland is still consumed with questions about what went wrong that April night. “We need to look at why this happened,” says George Pierson, a black city councilman who also happens to be a former warden of death row. “Everyone in Grapeland should feel some blame. Children aren’t raised just by their parents but by a community. We are part of the community.” Pierson, who oversaw 22 executions, sent a letter to the governor expressing his opposition to Napoleon’s execution. “He took a life,” Pierson says. “But justice is not equal. I saw inmates who had committed multiple murders, or who had killed blacks, who didn’t get the death penalty. Napoleon is not the worst of the worst.” For Napoleon’s friends, who have married and have children of their own, there is a yawning sense of guilt as life moves on. But no one’s burden is heavier than that of Ireland and Rena’s. The heartache of their son’s deed is worn for all to see, their faces lined with the disquiet of parents for whom sleep does not come easily. “Sometimes I think it must be a bad dream,” says Rena, who has been hospitalized twice in recent years for depression. “I’ve gone back and I just can’t understand. Where did we go wrong?” For Ireland, the anguish is no less than his wife’s. “I had to do a lot of soul-searching during the Jasper trial because I knew exactly what the father of [James Byrd’s killer] Bill King was going through,” he says. “That man may be the worst racist in the world, but I wouldn’t wish this hell on anyone.”

That night, beneath the lacquered Bible quotations and outstretched ceramic angel wings that line the Beazleys’ living room walls, they hosted a prayer service—as they do each month with fellow church members—in which they tried to summon forth divine assistance for Napoleon and the Luttig family. Sorrowful hymns drifted out into the night as friends and family crowded into the small brick house, their tears mixed with testimonials. “Show mercy, Lord,” Ireland exhorted, his voice choked with emotion. “Show mercy.” Standing behind him in the kitchen was his eighteen-year-old son, Jamaal, a Grapeland Sandies offensive guard who is now in the second semester of his senior year. The captain of the football team, Jamaal can bench-press 375 pounds, though his big, broad-shouldered build belies his shyness. He is a quiet, serious boy who harbors no dreams of athletic glory: Someday, he said, he wants to be an accountant. Jamaal has learned from his brother’s example; he picks his friends carefully, and he never strays far from home. “I’m not popular like Napoleon,” he said. “But if I get into other people’s business, I’ll get into something I don’t want to. I don’t want to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Jamaal told me this outside the Beazleys’ house as we looked up in the dark country night at the stars. They shone brightly above the line of hackberry trees, where his brother had once ditched his .45-caliber pistol, hoping that it would never be uncovered. Jamaal pointed out the North Star, then the Big Dipper. “I think I’d be pretty good at astronomy,” he said quietly, before resuming his study of the sky. It grew late, and I finally left, driving down the dimly lit streets of the Quarters, a place where even the best and the brightest can get dragged down. Jamaal stayed behind, still staring up at the stars. I hoped he would be safe.

- More About:

- Longreads

- Death Row

- Death Penalty

- Crime