This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On the morning of January 12, 1983, in a second-floor corridor of the Pentagon known as the Hall of Heroes, Paul Thayer was sworn in as deputy secretary of the United States Department of Defense. It was a proud moment for the 63-year-old Dallas executive. Margery Thayer, his wife of 36 years, stood to one side, holding the Bible on which he placed his left hand; Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, his new boss, stood to his right. Watching the brief ceremony were the nation’s top military brass, admirals and generals in full uniform. Also there were Paul Thayer’s closest friends, several of them prominent business executives who had taken time from their busy schedules to fly to Washington. Photographers snapped away, capturing the moment for posterity and the next day’s newspapers.

Paul Thayer, a college dropout who spent part of his childhood living in a tent, had led a charmed life. After quitting school, he became a World War II fighter ace, then a hot test pilot. Planes blew up all around him, but he escaped with nothing more than a broken tailbone. Then he entered the corporate world. By 50, he had risen to the chairmanship of the giant but troubled LTV Corporation; he rescued the company from bankruptcy, then led it to record profits. He became a national business leader, serving on boards of directors and as exploring chairman for the Boy Scouts of America. He earned more than $1 million a year, traveled the world in corporate jets, and bagged lions on safaris to Africa.

Within the stuffy business establishment Thayer was revered for his intrepid lifestyle and conservative values. When it came time for a Texan to lead the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Paul Thayer was the choice. After he helped Ronald Reagan push a tax bill through Congress, the grateful president invited him to the Oval Office to offer his personal thanks. Now, two years before he had planned to retire from LTV, Thayer was giving up his fat salary to accept an appointment as the Pentagon’s number two man—in effect, as manager of one of the biggest bureaucracies on earth. It was yet another extraordinary challenge, one of the most difficult and powerful jobs in government. It would be, Thayer told his friends, the perfect finale to his career.

Instead, it became the stage for his greatest humiliation. Early this year Thayer returned to Dallas prematurely, his political career shattered, his reputation tarnished, his marriage shaken. He had been done in by a couple of rookie attorneys from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, whose investigation into insider stock trading had exposed intimate details of his personal life. Their discoveries, leaked to the newspapers, forced Thayer out of office. His resignation took effect on January 12, 1984, exactly one year after he took his oath of office in the Hall of Heroes.

In a 43-page civil complaint, the SEC accused Thayer, while at LTV, of illegally passing tips about secret corporate developments to a circle of eight friends—a group that used the information to net $1.9 million on the stock market. On five separate occasions, members of the group bought stocks whose price went up following corporate developments disclosed a short time later. Each time, Thayer had advance knowledge of that news. “You might be able to explain away one transaction,” says an SEC attorney. “You might be able to explain another. But the pattern you can’t explain.”

Equally stunning were the identities of those to whom Thayer stood accused of giving the inside information—a group portrayed as his close friends, people he met for “lunches, dinners, trips, vacations, and social gatherings.” They included Sandy Ryno, a 38-year-old former LTV receptionist who quit her job in 1978 to become Thayer’s mistress; Billy Bob Harris, a flamboyant Dallas stockbroker known for his wild parties, celebrity buddies, and gorgeous girlfriends; and Malcolm Davis, a convicted gambler whose home the FBI raided in 1975, discovering stacks of betting records and $65,000 in cash. It was almost as though, said one of the lawyers in the case, Paul Thayer had a second life.

In fact, that was exactly what he had. For years Thayer traveled in two different worlds. In one, he was the conservative apostle of big business, jetting about the country to preach the virtues of industry, morality, and a balanced budget. In the other, he was slipping away from his wife and his responsibilities to carry on an affair with a woman just four years older than his daughter, an affair that continued even while he served in the Pentagon. He took his mistress with him on trips to Canada, to Europe, and to the Virgin Islands. And he helped her buy a new $200,000 home with a swimming pool. Like many men of wealth and power, Thayer had had his share of flings over the years. But this relationship was different. Says one close friend who knew about the involvement, “I think he was in love with Sandy.”

If Ryno was the reason for Thayer’s second life, Billy Bob Harris was at its center. According to the SEC, Harris served as the conduit for the illegal stock tips, taking Thayer’s inside information and funneling it to the rest of the group. It was through Harris, too, that Thayer became linked to the others who were later accused of cashing in on his information. Harris brought him together with Gayle Schroder, a Houston-area banker who loaned Thayer money and wrote Ryno’s mortgage. Through Harris, Thayer also met Julie Williams, a 26-year-old aerobics instructor who was the stockbroker’s girlfriend; Doyle Sharp, a Dallas surgeon; Julie Rooker, a Braniff stewardess who was Sharp’s girlfriend; and Malcolm Davis, who was out of prison and running a small insurance agency. The last defendant, Atlanta stockbroker Billy Mathis, a former New York Jets halfback, was linked to the case through Harris as well. Though Mathis says he never met Thayer, the SEC has accused him of buying stock on the basis of Thayer’s tips, relayed by Billy Bob Harris.

That collection of associations produced Paul Thayer’s tragic fall—and lay at the heart of the allegations against him. Normally, the SEC tries to prove that a tipster made money from his information. But in this case, because Thayer did not make any money, the SEC must establish some other motive. Here, the contention is that Thayer set out to enrich Ryno and the others in order to enhance his relationships with them. The intimacy within the group, the government lawyers argue, provided both motive and opportunity for Thayer to disclose inside information.

The SEC’s scenario raises intriguing questions. Why would Paul Thayer, a prominent man who has lived an exemplary life—at least on the surface—need to give his friends stock tips in order to ingratiate himself with them? And why, given his estimated net worth of $10 million, would he resort to such a risky method of supporting his mistress? He found plenty of easier ways to give her money without his family’s finding out. Furthermore, Thayer’s relationship with his codefendants was not nearly as intimate as the SEC complaint suggests. Except for Ryno, they were more Harris’ friends than Thayer’s; of the rest, he had extensive contact only with the stockbroker, Williams, and Schroder. In addition, the group’s trading pattern was inconsistent. None of the defendants bought all five stocks, and in two cases, the purchases were relatively small. If the defendants knew from Paul Thayer’s information that they had a sure bet, why didn’t they load up on all the stocks and make even more money?

Those issues will be central to the SEC’s case against the defendants, all of whom say they are innocent. Under zealous new enforcement chief John Fedders, the SEC has been waging an unprecedented and much-publicized war on insider trading. “Put simply, it’s nothing more than stealing by people in white shirts and suspenders,” says Fedders. The defendants say they are the innocent victims of that crackdown, guilty of nothing more than smart investing and a run of good luck.

For all the publicity it attracts, the law against insider trading is both vague and weak. The practice is so common and so difficult to detect that some people don’t believe it should even be illegal. While the SEC can suspend stockbrokers, it does not have the power to bring criminal charges, and even when it wins in court, it can do nothing more than force those who traded illegally to cough up their improper profits and promise not to do it again.

As a result, most insider trading cases are settled out of court. In this case, however, a settlement is unlikely. Paul Thayer is a stubborn man who can afford the cost of litigation, and he has declared his intention to fight to the finish. A trial will unearth more detailed revelations about his relationship with Sandy Ryno, yet he considers it the only way to clear his name. The trial is set to begin January 7 in Dallas.

The defendants have more than the SEC to worry about. After filing its complaint, the SEC referred the matter to the Justice Department for investigation of criminal charges of fraud, obstruction of justice, and perjury. Among other matters, federal prosecutors are examining whether Billy Bob Harris lied to the SEC in an attempt to conceal Paul Thayer’s relationship with Sandy Ryno.

It is impossible to say with certainty whether Thayer passed corporate secrets to the eight other defendants. Even the SEC, which investigated the case for more than fourteen months with the help of a secret informant, has only circumstantial evidence of that. But it is possible to reconstruct the events that brought down one of the government’s most powerful men, to relate for the first time the defendants’ explanations for the large profits they earned in a short period of time, and, most of all, to take a look inside Paul Thayer’s secret life—to show how the intersection of ambition, greed, and power brought nine people together in a way that has changed their lives.

The Group

A Real Flyboy

I spoke to Paul Thayer in late July. We talked in the company of his attorney, under strict ground rules: Thayer would answer no questions about his relationship with Sandy Ryno and the others or about the facts of the SEC case against him. On that, he would stand by the denial of wrongdoing he issued when he resigned from the Pentagon.

Despite his troubles, Thayer looked relaxed and fit. He is a striking, solidly built man, about six feet tall, with silver hair, bushy gray eyebrows, and a square jaw. He wore a light suit, dark sunglasses, and, as always, three pieces of jewelry: a Rolex watch, a gold elephant’s-hair bracelet, and, on his left hand, a black and gold fraternity ring that is his single superstition. He has worn it continuously since World War II, when it was lost, then recovered from the bilge of his Navy fighter after a combat mission.

Above all, Paul Thayer projects utter confidence in his own abilities. He speaks slowly, with the calm of a man accustomed to tough scrapes. In April 1982 he was practicing stunt flying in a replica of his wartime Corsair when the plane’s oil pressure suddenly dropped and its single engine went dead. Unable to put the landing gear down, Thayer, instead of bailing out, crash-landed the crippled fighter in a pasture thirty miles east of Dallas, walked three quarters of a mile to a telephone, and ordered an LTV helicopter to pick him up. “Routine dead-stick landing,” he later groused.

Thayer approaches life with the attitude of a test pilot. At age 63, he personally aired out the Pentagon’s hottest supersonic planes before deciding how much money to budget for them. “I’ll always fly, as long as I can pass a physical,” he says. “It’s a sensation that’s very difficult to describe. To those who love flying, it has a sense of freedom about it that’s very difficult to simulate on the ground. . . . Being able to operate in three dimensions is a sensation I never get tired of.”

He found boardroom life less captivating. He says he accepted the Pentagon offer because he had been at LTV long enough. “There were times when the corporate environment was a little boring. I wouldn’t say it was the rule. At some time in their life, everyone would say they’ve gotten a little bored with the situation.”

Friends say Thayer remains deeply bitter that anyone has dared to question his integrity. But he denies that the episode has affected his outlook. “I have all my friends,” he explains, “and that’s what life’s all about.”

William Paul Thayer was born on November 23, 1919, in Henryetta, Oklahoma, but he didn’t stay there long. His father was an oil field driller who moved his brood from town to town across Oklahoma and Kansas, following the rigs; the family spent one summer living in a tent. By the time Thayer reached the fourth grade, his father had settled into a job as a drilling contractor, and his family had settled into a home in Wichita. Thayer thought he wanted to follow his father’s path. He worked summers during high school in the oil fields and dropped out after his first year at Wichita State to become a roughneck. He returned to school as a sophomore at the University of Kansas, expecting to study petroleum engineering.

With war looming, the government was subsidizing civilian training programs to build a pool of potential pilots. Thayer signed on, and his life was forever changed. He left Kansas after his junior year to attend military flight school, choosing the Navy, he later said, because he had heard “it took a little more expertise and a little more training to land on an aircraft carrier than it did on a field.”

Flying from carriers based in the Mediterranean and the South Pacific during World War II, he shot down a Vichy French fighter and five Japanese Zeros, and he destroyed nine more enemy planes on the ground. He emerged in 1945 with a Distinguished Flying Cross and an Air Medal and, at age 26, became a commercial copilot with TWA. While living in San Francisco, he met a blond TWA stewardess named Margery Schwartz. They were married on Valentine’s Day, 1947.

But compared with dogfights over the Philippines, the San Francisco–Albuquerque run didn’t offer much challenge. Thayer became bored. After a year, he answered a newspaper ad for test pilots at Chance Vought Aircraft, in Bridgeport, Connecticut. In his first eight months there, three pilots were killed and three others quit, but Thayer began a 22-year climb up the company ladder. As an experimental test pilot, he became the first man to break the sound barrier in a Navy jet.

A few years later, the company moved to Grand Prairie, just west of Dallas. Thayer, in his early thirties, had begun to turn heads. Test pilots had, well, an air about them, and to Paul Thayer it came naturally. “He was a real flyboy,” says one woman who worked in the company’s accounting department at the time. “He was a real glamorous man and good-looking—full of all kinds of piss and vinegar.”

Men liked him too. Even as he rose in the company, Thayer kept his easygoing charm. He was on a first-name basis with the lowliest subordinate, and those who worked for him liked his direct manner and willingness to delegate responsibility.

In 1955 he became a company vice president, with a seat on the board of directors. In 1959 he became vice president and general manager of the aeronautics division. After James Ling’s hostile takeover of Chance Vought in 1961, Thayer emerged as a conciliatory force. When the company’s president resigned following the merger, Thayer became president and a director of the newly constituted parent firm, Ling-Temco-Vought—better known as LTV.

Vought, which was later renamed LTV Aerospace, flourished under Thayer’s control, quadrupling its sales to $800 million with the help of a massive contract to build A-7 fighters for the Air Force and the Navy. Enjoying his success, he built himself a 7524-square-foot home and a swimming pool in an exclusive North Dallas neighborhood. He was not one to spend his time scheming to get ahead. Thayer happily spent his free hours scuba diving, motorcycling, skiing, playing golf, and—most of all—flying airplanes. Promotions just seemed to find him, sometimes even before he wanted them. “I honestly can’t say I ever had a job I didn’t like,” he told one interviewer. “But there have been times when an opportunity came to go up the ladder before I wanted it to.”

Such an opportunity came again in 1970. By then Ling had built his conglomerate into the nation’s fourteenth-largest industrial corporation, a behemoth with total sales of $3.75 billion and 125,582 employees. In addition to Thayer’s aerospace subsidiary, LTV’s remarkable portfolio at its peak included Braniff Airways; Wilson Sporting Goods; Ling Altec Electronics, a stereo equipment manufacturer; National Car Rental; LTV Electrosystems, the forerunner to E-Systems; Jones and Laughlin steel; Wilson Beef and Lamb, a large meat-packing company; and Okonite, a huge wire, cable, and floor-covering company. But Ling’s empire was an unwieldy one; the master of acquisition had paid too much for several of the properties and too little attention to how all of them were run. When earnings fell way short of projections, Ling found himself short of cash to meet LTV’s enormous debt.

In May, as the company teetered on the brink of bankruptcy, a rump group of Dallas businessmen led by E. Grant Fitts, Troy Post, and banker Robert H. Stewart III seized control of the board from Ling. Two months later, Fitts, the leader of the insurrection, called an emergency meeting to pick Ling’s successor. They chose Paul Thayer. But Thayer told the LTV directors that he was happy running his airplane subsidiary. “I was like a kid with his own candy store,” he said later. Turn it down, the board members replied, and you may end up working for someone you don’t like. Thayer accepted.

He toured the country to calm LTV’s bankers. He walked the plants to give pep talks to employees. And with LTV’s chief financial officer, he developed a battle plan to turn things around. Thayer told his lieutenants that every LTV subsidiary was a candidate for sale—and many of them went: Braniff, E-Systems, Okonite, and Altec were all gone within two years. The debt was cut to a manageable level, and the company started paying attention to how its remaining subsidiaries were run. By 1972, LTV had returned to profitability. Thayer had raised the corporate phoenix from the ashes.

In 1974, with LTV reporting record profits, Thayer raided the Xerox Corporation for help with the company’s management responsibilities. He named Ray Hay president of LTV. For Thayer, the burdens of management were lighter than they had been since he had become LTV’s chairman.

Thayer began to raise his public profile, to emerge as a prominent figure in the national business community. He gave speeches about federal procurement procedures and testified at public hearings. He joined business groups—the Conference Board, the Business Roundtable, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce—and became a national director of Junior Achievement. He granted more interviews with the press, in which he talked about the problems of government regulation and the need for a strong defense. LTV issued press releases containing Thayer’s comments on President Carter’s economic policies. The company took out full-page ads in national newspapers, offering opposing sides on controversial topics; the ads included a column titled “What LTV Thinks,” under a byline and photograph of Paul Thayer.

A Neiman’s Kind of Girl

Sandra Kay Ryno started working at the LTV Corporation in September 1966, at age 21. Born in San Diego, she had a Californian’s open, friendly personality, and she remembered names. It made her the perfect receptionist. Ryno worked on the fourth floor of the LTV Tower in downtown Dallas, where she greeted visitors to the company’s elegantly furnished executive offices, known within LTV as Mahogany Row.

Born Sandra Kay Huffman, she married Ronald Ryno of Lubbock at 19, two years before she went to LTV. Six years later, in 1970, the couple had their only child, Melanie Kay. They owned a lot on Lake Texoma, and they both drove to work in Ford Thunderbirds. But in 1972 they split up. When Sandy Ryno was 27, her life as a newly single woman began.

Ryno is an attractive woman, five feet four, 118 pounds, with blue eyes, a slender face, and a striking head of full brown hair. She has clean, elegant looks; she is the sort of woman who looks classy in a pair of blue jeans. But it is her manner that males find particularly beguiling. She has a glowing smile, a sparkle in her eye, and a sweet word for everyone. At LTV men hovered around her desk, making small talk. “She exuded sexuality,” says one former LTV vice president. “She just made men feel good.”

In 1974 Ryno bought a small house across the street from a park in a middle-class neighborhood in suburban Richardson. The neighbors immediately took a liking to the single mother but thought her a bit out of place. This was a Sears kind of crowd, and Sandy was a Neiman’s kind of girl. She took time to make sure her clothes and makeup were just right. She had a young daughter and she worked, but her house was always neat. She jogged, took vitamins, and lifted a pair of little barbells that she kept at home. She collected butterflies. “She’s very refined,” says Laurie Thomas, a neighbor who baby-sat for Ryno’s daughter. “She always struck me as the type of person who would know what to do with money if she ever had it.”

Ryno didn’t seem to have much money, but several of the men she went out with did. Once, when she returned home late after a night out, her date handed her a $100 bill to pay the baby-sitter. Men just seemed to want to impress Sandy. Neighbors viewed her involvement with wealthy, successful men as a natural outgrowth of her desire to get ahead, to gain entrée to a profession that would provide a comfortable living for herself and for Melanie.

But at LTV, where Ryno spoke freely about her personal life, some of the other women began to think of her as a shameless gold digger. “Sandy’s got to look them up in Dun and Bradstreet before she’ll get serious with them,” one woman joked. One day Sandy came home with a man she didn’t need to look up in Dun and Bradstreet. A neighbor recognized him instantly: it was Paul Thayer.

A Quiet Place to Go

To Thayer’s friends, it seemed unlikely that Sandy Ryno would become his mistress. He and Margery had been married a long time, and appeared happy together. They were united particularly by their adoration of their only child, Brynn, now an actress on the television soap opera One Life to Live.

Genteel where Paul was salty, low-key where he was aggressive, Margery Thayer, most of all, was thoroughly devoted to her husband. She took up golf so she could spend more time with him, and she accompanied him on a big-game safari. But like many Dallas executive wives, Margery busied herself with charity work and social organizations, becoming a volunteer worker for the Dallas Academy of Retarded Children and serving as president of the alumnae chapter of the Delta Delta Delta sorority. She also played a good game of gin. As one family friend put it, “She was a very fine corporate spouse.”

Along the way, she became remarkably detached from her husband’s activities. He traveled often, and she asked no questions. She called the office infrequently and showed up there even less often. Doris Hawk, Thayer’s secretary since 1955, kept the family books, investment records, and checks; Margery ran the household with a separate account. She discovered that her husband had sold $24,000 worth of LTV stock to pay a Las Vegas gambling debt by reading it in a magazine. Says a longtime associate: “She has led a very, very sheltered life as far as he’s concerned.”

For his part, Thayer was discreet about his extramarital relationships. There was gossip at LTV that his machismo carried over into the bedroom, but only a few of his closest friends and business associates knew more than rumor. Those who traveled with him were among them. According to one former LTV executive: “It was proved on more than one occasion that he was a womanizer. Whenever he was out of Dallas, he was frequently with some woman.”

Most such episodes were little more than one-night stands, but Sandy Ryno was different. “This relationship was important to him, more so than any of the others,” says one close friend, a man who attended Brynn’s wedding. “He was more guarded about this than about something else I might know about.” Thayer’s involvement with Ryno began while she was working at LTV. They agreed she should leave the company, and she quit in October 1978. The relationship remained a secret to those who worked at the company.

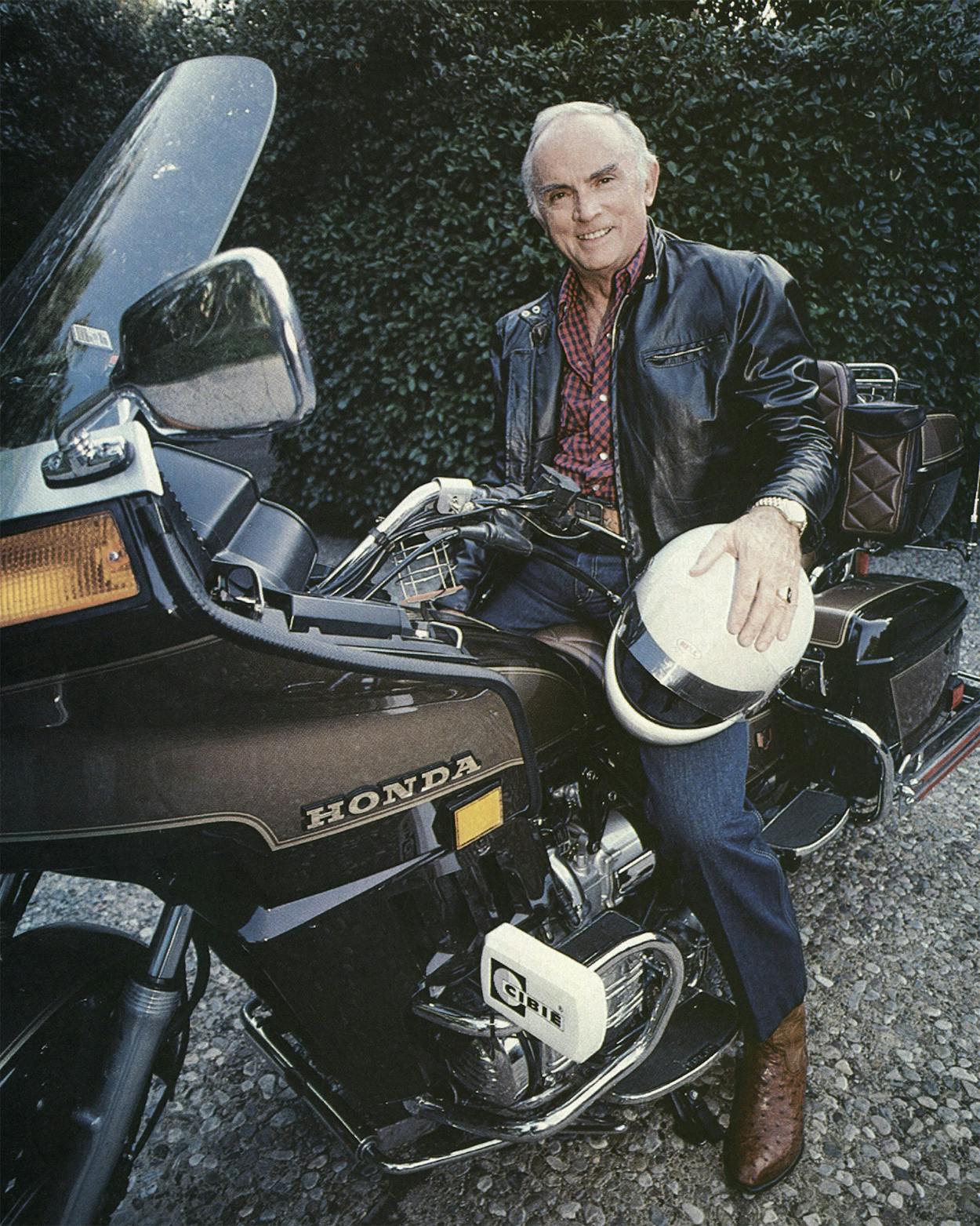

On Sandy Ryno’s block in Richardson, however, her involvement with Paul Thayer was no secret. Ryno introduced Thayer to her neighbors simply as “Paul,” but they knew he was not the average paramour. By 1980 they had become used to seeing him pull up to her small home on his Honda Gold Wing motorcycle—the biggest one made—or in his black Datsun 280Z sports car or in his large limousine with the telephone inside. One neighbor, Charles Davis, a program manager with Rockwell International and Laurie Thomas’ father, liked to chat with him about motorcycles. Thayer came by about once a week, sometimes less often, and sometimes he and Ryno would go on trips out of town.

They spent weekends fishing on Lake Texoma on the LTV yacht. Thayer enjoyed children, so Melanie joined them; noticing the bushy hair on his face, she took to calling him Eyebrows. Jason Davis, the neighbors’ son and Melanie’s friend, went along on some of the trips.

Ryno spoke freely to her neighbors about her new relationship. “The way she talked about him, I just thought he was another boyfriend,” says Laurie Thomas. “I was shocked when I found out he was married.” “We asked her one time why she didn’t date someone younger,” says Dale Davis, Laurie’s mother. “She said she cared for Paul as a person. I think [her house] was a quiet place for him to go.” They asked her about going out with a married man. “It did trouble her,” says Davis. “She told me she didn’t want to come between him and his wife. I think she wished it could have been the other way.”

The neighbors say Ryno was intent on finding a situation that would make her financially independent. “She really wanted to move up and be happy and get ahead,” says Laurie Thomas. “Paul respected that and wanted to show her how.”

When she quit the LTV job she had held for twelve years, Ryno turned to fields in which her new contacts could make her money: insurance and real estate. She began work in November 1978 with an insurance firm on Preston Road in North Dallas. Friends from LTV began receiving calls from Ryno, who said she was hunting for business. After changing jobs twice more in the next two years, she was hired in November 1980 to work for Transworld Insurance Brokers of Beverly Hills, California. Her new boss was Fred Wilson—a friend of Paul Thayer’s. It was not the first time Thayer’s friends had helped Sandy Ryno earn a living. Thayer had already sent her to see Billy Bob Harris.

The Party Palace of Dallas

A few years back, visitors to Dallas who knew where to go had no trouble taking advantage of Billy Bob Harris’ hospitality: he left his door unlocked. People would wander in, fix themselves a drink, and wait for someone to show up. In the sixties and early seventies Harris’ two-story townhouse in the Oak Lawn area was the party palace of Dallas.

The crowds gathered every Friday night, sometimes as late as 2 a.m., after the clubs had closed. There were musicians—famous ones like Ray Wylie Hubbard and the Gatlin Brothers—and football players—like Craig Morton and Donny Anderson and Walt Garrison. And women! There were gorgeous women all over the place—models and stewardesses and women who worked in public relations, all of them cast from a Hugh Hefner mold. The place rocked until dawn, and sometimes past noon. No wonder the city’s hip young crowd knew Harris as “Mr. Dallas.” He had come a long way from the dusty little Panhandle town of Gruver.

Born in 1939, the only child of churchgoing Methodists who raised wheat and cattle and owned a filling station, Harris ran track for the local high school. He was fast enough in the 440 to earn scholarship offers from SMU and North Texas State. After a short time at SMU, he dropped out and enrolled at North Texas. He likes to say he crammed four years into five and got a degree in rock and roll. After graduating as a psychology major, Harris reluctantly returned to Gruver. Briefly. After three months on a tractor, he told his father he was going to Dallas to be a stockbroker. “Don’t those people make money off their customers?” his father asked. “How many people do you know there?” “None,” Billy Bob responded. “Maybe I can get to know some.”

Harris moved to Dallas, where he slowly began to meet people and win customers. Only one thing cramped his style: he was married. During his senior year he had proposed to a classmate who was a beauty queen from Memphis. Fifteen months after the wedding she sued for divorce, saying Billy Bob had “gambled to excess, absented himself from home overnight and for long periods of time without giving plaintiff any reason for such absences and has told plaintiff he does not love her.” A judge granted the divorce in January 1965.

Harris found an apartment with Donny Anderson, a friend from childhood who had become a star running back with the Green Bay Packers and lived in Dallas during the off-season. The two joined a circle of hard-partying professional football players, celebrities, stewardesses, and models—a group portrayed in Pete Gent’s popular novel, North Dallas Forty. (A barely disguised Billy Bob Harris appears as a character in the book.) One night Harris and a young woman were driven around Dallas in flagrante delicto on the roof of a white Cadillac. In 1968 Harris and Anderson moved into the townhouse on Rawlins Avenue in Oak Lawn. Harris hired an interior decorator and also added his own touch: more than a dozen telephones and framed photographs of hundreds of his closest friends.

The two men roomed together until Anderson got married in 1971. They made an unlikely pair: the blond, muscular halfback with the rugged good looks and the short, scrawny stockbroker with the round face and rapidly thinning hair. During the week Harris spent much of his free time lounging about the swimming pool. He fretted endlessly about his appearance and sported a tan after everyone else in town had faded to white. He was particularly worried about losing his hair; he combed a thatch of it straight down to cover his bald spot and pasted it in place with hair spray.

In 1973 Harris began doing stock market reports on KVIL, a popular Dallas radio station. His increasing prominence was helping him make good money, but he didn’t keep much of it. He seemed to have an attraction for bad business deals. Friends suckered him into a succession of them, and he lost a bundle.

His life grew more hectic, and at times he had trouble coping. On one occasion two women arrived at the townhouse and found a pair of exotic birds dead on the floor; Harris had left town for several days and forgotten to make arrangements for their feeding. He was arrested in 1975 for drunk driving and placed on six months’ probation after pleading guilty.

Harris and Cowboys quarterback Craig Morton, hoping to cash in on their contacts, opened Wellington’s, a nightclub near Bachman Lake. A Dallas attorney put up much of the money, and Harris ran the place. It was the hottest disco in Dallas until racial tensions between black and white customers began to hurt the business. In 1975, when two black men abducted a young white couple from the parking lot, brutally beat the woman, and murdered the man, Harris and his partners pulled out.

That experience—and a glance at his bank account—helped persuade him to slow down. Even while he had been maintaining a frenetic pace, he had attended church regularly. Now he sat down with his preacher, Don Benton of the Lovers Lane Methodist Church in North Dallas, and confided his problems. “He wanted to change his lifestyle some,” says Benton. “He came to me and laid out his life.” The open houses came to an end. Harris began a regular routine of running and lifting weights. He got more involved in charity work. He paid more attention to his job. “Instead of leaving at three o’clock and coming home and getting a suntan, I worked late,” he says. Always a large producer for A. G. Edwards, a St. Louis–based brokerage firm, he became the company’s top broker.

Billy Bob Harris was becoming Dallas’ most prominent stockbroker. Along with his radio work, he began doing stock market reports on WFAA-TV. His friend, anchorman Tracy Rowlett, arranged the deal. Harris was terribly nervous and awkward on the air at first, but he worked hard at it—even practicing nights on TelePrompTer equipment at the Kim Dawson modeling agency—and improved.

Harris’ high profile enhanced his business. His friends became his customers, and his customers became his friends. Over the years, it has become a large, eclectic group. His clients have included the late Ruth Carter Stapleton, Jimmy Carter’s evangelist sister; Rex Cauble, the Western-wear tycoon recently sent to prison for racketeering in drugs; and Malcolm Davis, one of the SEC defendants who in 1977 was sentenced to three years in prison and fined $10,000 after being convicted of helping to run a gambling operation. According to court documents, the apartment for the business was provided by Billy Bob Harris, who rented it using the name of Dallas oilman Jack Vaughn, one of his biggest customers. The only problem was that Vaughn didn’t know anything about it until FBI agents contacted him.

For those Harris considers his friends, no request is too large, no imposition too great. “If I needed twenty thousand dollars by sunset,” says KVIL program director Ron Chapman, “he’d find a way to come up with it—and never ask me why I needed it.”

Friends and Clients

It was Paul Thayer’s daughter who introduced Thayer to Billy Bob Harris. In the early seventies Brynn joined Harris’ social circle. She became close friends with Harris and invited him home to meet her parents. When she visited her parents on holidays after moving to New York, she often had Harris join them for dinner.

Eventually Thayer started to use his daughter’s friend as a stockbroker. Harris had been making good money trading commodities, and he began trading them for Thayer. Like many of the broker’s customers, Thayer gave Harris discretionary authority over his account—the right to buy and sell without first consulting him. When Harris made money for him, Thayer began trading stocks through A. G. Edwards as well. Brynn Thayer and Doris Hawk, Thayer’s secretary, also became Harris’ customers.

In March 1980 Harris took a call from Paul Thayer, who told him, “I’m going to send you a new client.” Later that week Sandy Ryno showed up at A. G. Edwards office in downtown Dallas. “I started doing business with her, just like I do business with hundreds of other people,” says Harris. Ryno had plenty of money to play with; she opened her account at A. G. Edwards with $50,000. With discretionary authority, Harris began trading stocks and commodities for Ryno; his luck continued, and he made money for her. Occasionally she would call him with her own ideas of what to buy.

Although Harris was fond of Brynn and Margery Thayer—and knew Ryno was Paul’s mistress—he wanted to do whatever he could for the chairman of LTV. “I’m not going to lecture him on what he should or shouldn’t do,” says Harris now. “I quit trying to second-guess people and their relationships a long time ago.”

By year’s end, Ryno had decided to build a new house for herself and Melanie. She talked to Harris about it, and he phoned Gayle Schroder, his friend who owns banks near Houston, in Baytown and Manvel. The Schroder-Harris friendship was testimony to the maxim that opposites attract. Schroder has middle American virtues and lifestyle: an attractive wife, three wholesome children, a work-your-way-up career. He started his career as a teller and has spent his lifetime working hard in the banking business. Now he runs two small banks of his own and takes Fridays off to play golf at the Golfcrest Country Club, across the street from his large home in Pearland.

“He asked me if I’d be interested in financing a house for Sandy Ryno in Dallas, Texas,” Schroder recalls. “I said, ‘Who is she?’ ‘It’s a friend of Paul Thayer’s,’ said Harris.” Schroder told Harris he would be happy to handle her mortgage.

At the time Schroder and Harris had plans that made them particularly eager to ingratiate themselves with Paul Thayer. Schroder had once owned a bank in Dallas and wanted one there again. He and Harris, who had been a director of Schroder’s old bank, were going to do the deal together. They had bought a choice piece of land in Oak Lawn and cleared the site for building. But they knew that to attract customers they needed a group of locally prominent directors, the kind of people whose names would bring in business. Harris suggested Paul Thayer for board chairman.

Schroder knew that was impossible. Thayer was a director of the Mercantile Texas Corporation, a billion-dollar bank holding company, and he obviously would not quit that job to chair the board of their tiny, nascent bank. But they thought he might help in some other way—by referring customers, perhaps, or by arranging for some other high-level LTV executive to serve on the board. Harris was working to bring Thayer and Schroder together when Sandy Ryno announced that she was in need of the house loan. “It was just another opportunity for me to get to know Paul better,” says Schroder. “I promoted that relationship as much as I could for the selfish reasons I had.”

Ryno sold her little house in Richardson, and in May 1981 she and her daughter moved into their new home: a 3076-square-foot brick house with a swimming pool on a quiet cul-de-sac beside a man-made lake. The house was part of an exclusive new subdivision in Garland. She paid for the home with a $170,000, thirty-year mortgage from the First American Bank and Trust Company of Baytown.

By mid-1981 Thayer and Sandy Ryno had begun their affair, Billy Bob Harris had become their broker and man Friday, and Gayle Schroder had begun to make them loans. The web of relationships that would produce Paul Thayer’s fall had been spun.

The Deals

Ripple Effect

That fall, the president of LTV’s aerospace division met with Paul Thayer to propose a takeover of the Grumman Corporation. To Thayer, the move seemed a splendid one. LTV’s lucrative contract for building jet fighters was about to run out, leaving the company out of the business of building war planes for the first time in forty years. But Grumman was the Navy’s prime supplier, with enough orders for F-14 fighters and A-6 attack planes to last for years. Moreover, Grumman’s stock was depressed. It would be possible to make a tender offer well above the going price of Grumman stock without paying more than the company’s assets were worth.

On Thursday, September 17, executives at the Grumman compound in Bethpage, Long Island, noticed a strange thing happening to their company’s stock. In a week in which Grumman had traded fewer than 6000 shares a day, 61,300 shares had suddenly changed hands. The curiously heavy trading continued through Monday afternoon, when a call came in to Grumman’s executive suite from Paul Thayer. The LTV chairman spoke to Joe Gavin, Grumman’s president, and told him LTV wanted to talk to Grumman about a merger.

So that was it! Someone had been buying up Grumman stock in anticipation of a takeover bid. Gavin first assumed it was LTV. But when he called Thayer back to tell him Grumman had no interest in a friendly merger, Thayer assured him it was not LTV. Then who could have been buying the stock? Thayer’s company had not yet announced its plans to attempt a takeover. That information was supposed to be secret.

In fact, it was not Thayer’s company that had bought the stock but some of Thayer’s friends—and a group of their friends. Here’s how the SEC believes it worked: Days before LTV’s tender offer became public, Thayer tipped Billy Bob Harris. Nervous about using the information himself or even handling Grumman trades for the others, Harris passed the information to three of his closest friends: Malcolm Davis, Gayle Schroder, and Billy Mathis, a former pro football player working as a broker in Atlanta. Davis and Mathis then passed the tip on to their friends in exchange for a share of the profits the information would produce. Those people in turn passed it to yet another group. The result was the extraordinary jump in trading volume that so bewildered Grumman executives. Purchases by the entire group, says the SEC, accounted for an incredible 70 per cent of the Grumman shares traded on September 17 and 18. The pattern of relayed information, emanating from Thayer, being passed on by Harris, and rippling out in ever-widening rings to others scattered about the country, would be repeated again and again, according to the SEC.

Schroder bought 13,000 shares of Grumman. Davis, a competitive-backgammon aficionado, went in with two of his backgammon buddies on 20,000 shares, in an arrangement that would give him half the profits from the stock without his investing any money; five other backgammon players around the country also bought Grumman on Davis’ recommendation. Mathis bought $700,000 of Grumman bonds and 21,000 shares of stock; he recommended Grumman to a fellow broker who later gave him half the profits resulting from his purchases. All these large investments were made by the time trading ended on Tuesday, September 22.

At a press conference in New York City before the stock market opened Wednesday morning, Thayer announced LTV’s tender offer of $45 per share, a 70 per cent premium over the previous day’s closing price. The New York Stock Exchange delayed trading in Grumman because of the news. When trading resumed that afternoon, Grumman rose more than $9 a share.

Grumman fought the LTV takeover bitterly, and in October it won a court order barring the takeover indefinitely. A month later, when Thayer issued a terse statement saying that LTV was terminating its tender offer rather than endure a long and costly court fight, Grumman stock tumbled to about where it had been before the offer had inflated the price. But by then Billy Mathis, Malcolm Davis, Gayle Schroder, and the others had long since sold their Grumman shares. Mathis, with the help of his profit-sharing agreement, earned $562,670. Schroder made $176,383, and Davis, without risking any of his own money, earned $123,100.

“I Wasn’t Born Last Night”

Although Paul Thayer was disappointed that Grumman had slipped from his grasp, he could take solace in the performance of his own company. As 1981 ended, he received confidential reports that LTV was heading toward its best year ever. He scheduled a meeting of the board of directors’ audit committee for 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, January 27, to release the good news. The committee would rubber-stamp the glowing profit figures and make them public. On Thursday and Friday the board’s finance committee and the full board would meet to approve a second piece of good news—distribution of LTV’s first quarterly common stock dividend in twelve years.

At 9:32 a.m. on Wednesday, as the LTV board was meeting, Billy Bob Harris bought 10,000 shares of LTV—8500 for Schroder and 1500 for Ryno—at about $14 per share. Forty-five minutes later, the Dow Jones wire carried the news that LTV’s fourth-quarter earnings had jumped 95 per cent, giving the company record profits for the quarter and the entire year. After the announcement, Harris bought another 10,000 shares of LTV for himself. By closing, LTV’s price had climbed to $15.75 a share.

On Thursday, Thayer’s California friend Fred Wilson, the man who had hired Sandy Ryno, purchased 6000 shares of LTV. Harris bought more LTV for his father and three other customers. The next day LTV announced a quarterly dividend of 12.5 cents a share. Schroder and Ryno sold their LTV stock the following Monday. Schroder earned $16,930, Ryno $2713. Harris made a $7622 profit for his father but held on to his own shares until April 8, when he sold them at a loss of almost $11,000.

To SEC attorneys, the LTV purchases show that Paul Thayer’s friends, after trading Grumman without detection, were making bolder use of his information. This time, the government lawyers say, they not only traded stock in Thayer’s company but made no effort to conceal the involvement of his personal stockbroker, Billy Bob Harris.

In the LTV trading, however, there are clear weaknesses in the government’s case. As the defendants are quick to point out, Harris didn’t buy stock for himself or his father’s account until after the earnings announcement, the news that produced the boost in LTV’s price. Although he purchased the stock before the dividend announcement, that revelation had no effect on the price. Why, if he had inside information, would he not have bought it earlier, when he bought stock for Schroder and Ryno? LTV’s higher earnings were also widely expected. The company had publicly disclosed terrific profits in the first three quarters of the year, and it was on many analysts’ buy lists.

Harris says no one would be so brazen as to use inside information from LTV’s chairman to buy LTV stock for the chairman’s mistress. “Can you see me asking him the earnings of LTV so I can buy for his girlfriend?” says Harris. “That’s the goofiest thing I can imagine. I might have been born at night, but I wasn’t born last night.”

Something Cooking

Both the LTV and the Grumman trading involved Thayer’s own company. The next three investments would be different. In each transaction, Billy Bob Harris and his customers would make quick profits on proposed mergers. In each case, Paul Thayer was an outside director of one of the companies involved in the deal.

The first took shape on January 29, 1982, when the Wall Street Journal reported a rumor that the giant Allied Corporation was preparing a bid for a Dallas oil and gas company called Supron Energy. Billy Bob Harris was not surprised at the report. In previous months, he and others at A. G. Edwards had tried to help Supron find an attractive suitor. But after a while Supron executives seemed to lose interest in his company’s efforts; they had even stopped returning phone calls. Now something seemed to be cooking.

In fact, Allied was preparing a bid for Supron. That weekend the Allied board of directors met in Key Biscayne, Florida, to approve the deal. Among the board members attending the meeting was Paul Thayer.

On Monday, February 1, the first trading day after Allied’s board meeting, Harris bought 3500 shares of Supron for himself and 1500 for Ryno. The SEC believes that Thayer tipped Harris and Ryno that the takeover bid was imminent. Harris says he didn’t even know Thayer was on the board of the Allied Corporation, that he had simply read the newspapers and put a few facts together.

Nine days later, Allied and the Continental Group revealed that they had reached an agreement to buy Supron for $35 a share. The price of Supron rose $3.50. Harris and Ryno sold their Supron stock the next day, earning $11,401 and $4440, respectively.

From Paris to Pearland

Paul Thayer was riding high, even though LTV’s record prosperity hadn’t lasted long. On April 27, in the midst of a steel slump that forced LTV to lay off more than two thousand workers, he announced a deep drop in his company’s earnings for the first quarter. That evening, he was in Washington for a gala U.S. Chamber of Commerce party at the Hilton. Thayer was there in a prestigious new role: he was about to begin his term as the group’s chairman. The place was filled with senators, congressmen, Cabinet officers, and White House aides. Thayer and his predecessor, PepsiCo chairman Don Kendall, posed for pictures with Interior Secretary James Watt.

Thayer’s chamber position had evolved from his increased political activity. In 1979 and 1980 LTV’s political action committees had contributed almost $200,000 to congressional candidates. In 1980 Thayer also had become involved in presidential politics. He had begun by backing the wrong horse, endorsing John Connally, but he later switched to Ronald Reagan. In January 1981 a few newspaper articles had even suggested that he would be appointed Secretary of the Air Force. Thayer scoffed at the reports, saying he would never accept such a modest position. But with the chamber appointment, he had been given a major platform. He would travel the country making speeches and visit regularly with Reagan to offer the perspectives of big business.

At LTV’s annual meeting on May 14, 1982, Thayer announced that company president Ray Hay would replace him as chief executive officer at the end of the year. Thayer said he would remain board chairman until 1984, when he planned to retire. Until then, he would spend much of his time working toward “improving the business climate in this country.”

Even as the demands on his public life accelerated, Thayer clung to his other world, his private life with Sandy Ryno. But it was getting harder and harder to keep them apart. He told his secretary to clear his schedule for the end of May. He was going on a trip to Europe to make speeches for the chamber and play a little golf. He told her that Billy Bob Harris had asked to tag along and would be joining him on the private jet. He did not tell her that there would be two other passengers on the plane: Julie Williams and Sandy Ryno.

The group assembled at Love Field on the night of Wednesday, May 26. Thayer had just gotten back from a trip to El Paso and Albuquerque, making speeches for the chamber, and he was tired. The plane had a pilot, but as usual Thayer climbed into the cockpit and took the controls himself. They flew first to St. Louis, where he had a meeting scheduled for the next day. A. G. Edwards has its headquarters in St. Louis, and Harris had made appointments to meet with several company executives while Thayer was tending to his business.

That business, according to the SEC, would soon involve Billy Bob Harris. Thayer was attending a meeting of the Anheuser-Busch board of directors. The company was in the early stages of picking an acquisition target, a search that would soon focus on a Dallas bakery and snack-food company called Campbell Taggart. In the weeks that followed, there would be ample opportunity for Thayer to tell the others about the secret plans of Anheuser-Busch. But Harris says there was never any such talk, that he didn’t even know Thayer was on the Anheuser-Busch board.

The group was airborne again by early afternoon, bound for Paris. After two days in France, they flew to Portugal, and then Thayer dropped the three others off in Milan, Italy. He stopped in Brussels to give a speech for the chamber and in Geneva, Switzerland, to play in the Rolex golf tournament. Then he rejoined the others, brandishing a Wilkinson sword he had won playing golf. After twelve days, they arrived back in Dallas.

By mid-June the Busch management had zeroed in on Campbell Taggart. Thayer flew to a board meeting in St. Louis on June 23, at which the directors authorized Busch executives to draft a takeover plan for a specific company, preferably Campbell Taggart.

That weekend, Thayer again retreated into the private world he shared with Sandy Ryno. On Friday, June 25, Harris called Gayle Schroder at his bank in Baytown. In his informal luncheons and dinners with Thayer and Harris, Schroder had often joked about the bowling alley he owned in the Houston suburb of Pearland, about the money the place was making and the way kids were drawn to its battery of video game machines. In truth, Schroder was proud of the place. He had converted it from a Gibson’s discount store, and now it was a booming, well-run business. “Paul and I and Sandy and Julie are thinking of coming down and seeing your bowling alley and playing Pac-Man,” said Harris.

The Schroders picked the group up at Hobby Airport in the late afternoon—they had flown down in a private jet—and drove straight to the American Bowling Center. “The idea was for Paul to see the bowling center deal, have dinner, get on the plane, and go home,” says Schroder, who described the visit. “Billy Bob promoted this trip. He was busy promoting this relationship between Paul Thayer and Gayle Schroder.” When they arrived at the bustling bowling alley, Schroder led them to the bar, called the Turkey Club, and his guests had drinks. Then Thayer headed for the Pac-Man machine. Amid a crowd of teenagers in a suburban bowling alley, the voice of America’s business community stood over a video game machine for more than an hour, playing game after game in an attempt to best his previous score.

Thayer was obviously enjoying himself, and Schroder was pleased. He had always held Thayer a little bit in awe. He told the cooks to fry up some steaks, and they set up a buffet in the banker’s paneled office upstairs. The three couples drifted in and out to get food, Schroder led a tour of the pinsetters, and they all took turns at the video games. Thayer suggested that they spend the night; the Schroders, whose two sons were away at college, had plenty of room in their neat, two-story colonial home on six acres along Cedar Bayou in Baytown. By the time everyone went to bed it was midnight.

The next morning they all gathered for breakfast by the oval swimming pool. Thayer confided that he was being considered for deputy secretary of defense. The matter was a closely guarded secret at the time, but Thayer trusted his friends to keep it quiet. Schroder chatted with Thayer about the bank he and Harris had planned.

After breakfast they decided to go boating. At the backyard dock they got into a speedy new 23-foot Chris-Craft ski boat, the fastest thing Schroder had. They motored around for a bit, then Thayer took over the controls and headed across Clear Lake, over by NASA, for lunch at the Regatta Inn. As they neared the dock, Schroder scampered up on the slippery bow of the boat, ready to grab the mooring. They were close, but Thayer thought they were coming in too fast. Suddenly he threw the boat into reverse. The ski boat roared backward, and Schroder went flying into the dock, scraping his leg and the side of his head on the barnacles. He hung from the pier, then pulled himself up. By the time the boat had been tied up, he was a bloody mess. The damage wasn’t serious, but it put a damper on the festive mood. Schroder cleaned himself up, and everyone went into the restaurant for a quick hamburger. Then they returned to the house and went on to the airport for the flight to Dallas.

Back at work on Monday, June 28, Harris called a research analyst at A. G. Edwards and discussed the possibility that Busch might buy Campbell Taggart. Harris denies that he acquired that notion during his weekend in Houston with Paul Thayer. On Wednesday and Thursday Harris began buying Campbell Taggart stock: 2000 shares for Ryno, 3100 for his father and stepmother.

Thayer spent the Fourth of July weekend at the resort LTV had built in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, playing in a charity golf tournament he sponsored with a former Olympic skier. Then he roared off into the west with a few LTV buddies—including a retired Dallas police lieutenant—all of them on their motorcycles. On the back of Thayer’s Honda was Sandy Ryno.

As they drove through the Rocky Mountains, across the northern U.S., and into Canada, Thayer checked in regularly with his secretary. On July 6 in St. Louis, Busch executives were preparing for a key meeting to discuss the proposed Campbell Taggart acquisition. Knowing that the meeting was about to begin, Thayer stopped to place a five-minute call to August Busch III, chairman of the company’s board of directors. Immediately after that, according to the SEC, he called Billy Bob Harris. They spoke for nine minutes.

The next day Billy Mathis started buying Campbell Taggart stock. Over the next four weeks, Mathis bought 30,800 shares of Campbell Taggart at a cost of $863,541. Mathis touted Campbell Taggart to his friends and customers, including Bert Lance, who recently resigned as chief of Walter Mondale’s presidential campaign, and Jake Butcher, the Tennessee banker whose empire later collapsed; both Lance and Butcher bought the stock. All told, Mathis’ recommendations resulted in the purchase of 106,000 shares of the nondescript Dallas bread-baking company. Mathis says he purchased and pitched the stock on the recommendation of a Bear Stearns analyst in New York. But the SEC believes Mathis was high on it because of a tip from Paul Thayer, relayed by Billy Bob Harris.

On Tuesday, July 27, Thayer again went to St. Louis, where the Busch board was to give its final review of the proposal to approach Campbell Taggart. Before he left, Thayer spoke to Harris. That day Harris bought 10,000 shares of Campbell Taggart for himself and 4000 for Ryno. The next morning the Busch board authorized management to approach Campbell Taggart to discuss a merger.

The July 28 board meeting ended between noon and 12:30 p.m. At 12:58 p.m. Thayer, using his telephone credit card at a pay phone in Brighton, Missouri, placed a five-minute phone call to Sandy Ryno. That day Harris bought another 25,100 shares of Campbell Taggart, accounting for 28 per cent of the stock’s trading volume on the New York Stock Exchange. By the end of the week Harris had accumulated 70,000 shares of Campbell Taggart for a large group of customers, at a cost of more than $2 million. He had bought most of the stock for himself and the six other Texans who would become defendants in the SEC case.

Gayle Schroder, who often placed his own orders, said Harris had used discretionary authority in purchasing Campbell Taggart for him. Malcolm Davis, however, was well aware of Campbell Taggart; in addition to buying 15,000 shares for himself, Davis was touting the stock to his own network of backgammon players. By August 2 six of Davis’ friends had bought a total of 22,000 shares of Campbell Taggart.

On the morning of August 3, before trading opened on the New York Stock Exchange, Anheuser-Busch and Campbell Taggart disclosed that they were holding preliminary merger talks—discussions that would immediately boost the price of Campbell Taggart shares and result in a merger announcement six days later. For the first time, all eight defendants profited from the stock trading. Mathis earned $146,829, Harris $24,401, Davis $32,329, Ryno $21,145, Schroder $5254, Williams $6216, Rooker $6216, and Sharp $2002. But Williams, Sharp, and Rooker—though they had socialized with Paul Thayer—were never active investors in the trading allegedly based on his information. Harris insists that he bought all of their shares on his own initiative. The three of them, he says, “wouldn’t know a stock from a bond.”

A Timely Investment

The next merger Paul Thayer was involved in was the biggest and messiest of them all: the bitter takeover fight between Bendix and Martin Marietta. Thayer’s involvement stemmed from his seat on the Allied board. Allied would play a major role in the deal. Billy Bob Harris and his friends, in turn, would make a major investment in Allied’s move. When all was settled, they were $689,106 richer.

Thayer first entered the picture on September 8, when he flew to Wyoming for the semiannual convention of the Conquistadores del Cielo, a fraternity of top-level aerospace executives. During the five-day affair Thayer entertained the group by climbing into a rebuilt Corsair fighter and putting on an acrobatic air show. While on the ground, he talked about the takeover fight with the chairmen of Martin Marietta and United Technologies, which had joined the battle on Martin Marietta’s side.

By September 17 secret negotiations had begun that would eventually break the impasse. Edward Hennessey, chairman of the Allied Corporation, talked to Bendix chairman William Agee (best known for his romance with Mary Cunningham) about how Allied could help Bendix stay out of Martin Marietta’s clutches. Hennessey suggested that Allied might serve as a white knight, buying Bendix stock to keep it away from Martin Marietta and United. Allied called a special board meeting for Monday, September 20, to consider the matter. By Sunday Thayer had received a memo outlining the white knight plan.

Allied’s involvement could have enormous consequences for investors. A white knight buying up Bendix stock would increase competition for shares, pushing up the price of the stock. But for investors ignorant of the secret discussions, the game was a risky one. Bendix shares had already risen in response to three weeks of bidding. Only the entrance of a white knight would send the price of Bendix up further, and with the stakes so high, there was no reason for the average investor to assume that one would appear.

But Malcolm Davis and his friends were willing to gamble, and gamble big—with the help, SEC attorneys believe, of a tip originating with Paul Thayer and relayed by Billy Bob Harris. On Monday, September 20, Davis bought 10,000 shares of Bendix for more than $566,000. One of Davis’ backgammon friends interrupted his visit to a rare-coin convention in New York on Tuesday to buy 20,000 shares, after making collect calls from a pay telephone to Harris and Davis.

At 12:52 p.m. on Wednesday, Harris bought 38,200 shares of Bendix—at a total cost of more than $2.3 million—most of them for people who would become defendants in the SEC case. It was a hefty investment in a speculative situation. As things turned out, it was also a timely one.

Allied and Bendix executives had cut their deal that morning. At 1:19 p.m. the New York Stock Exchange halted all trading in Bendix shares pending public release of the news. Twenty-seven minutes earlier, Harris had bought into Bendix. Seventeen minutes earlier, Billy Mathis had bought the last of his 12,500 shares of Bendix.

That afternoon the Allied board approved the friendly tender offer for a controlling interest of Bendix. Allied publicly announced an offer of $85 per share, a price sure to increase the value of Bendix stock.

When trading resumed after a three-day freeze, Harris sold or tendered all the shares he had purchased. For the stockbroker and his customers, the investment of $2.3 million had paid off. Malcolm Davis made $178,764, Harris $143,075, Schroder $77,388, Ryno $51,000, Sharp $28,383, Rooker $12,948, and Williams $12,698. On the same day, Mathis sold his shares of Bendix for a profit of $184,850.

When Republican governor Bill Clements called Paul Thayer to say he was recommending him to the White House for the job of deputy secretary of defense, Thayer knew he would accept an offer. It was a tough job, Clements told Thayer (Clements had held it from 1973 to 1977, under Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford), but an extremely important one. While the Defense Secretary spends much of his time before Congress and touring military bases around the world, the deputy secretary has the day-to-day responsibility for running the Pentagon.

Thayer had been the White House choice from the beginning, even though Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger preferred Pentagon general counsel William Howard Taft IV, his longtime aide and the great-grandson of the former president. But the White House considered Taft, 37, too inexperienced.

Over the summer, the FBI conducted an extensive background check on Thayer, interviewing many of his friends, including Billy Bob Harris. The deputy secretary would have access to the nation’s most sensitive national-security secrets. It was critical that there be nothing in his public or private life that could compromise him. After completing its investigation, the FBI told the White House the good news: Paul Thayer was clean.

So it was that in November 1982, newspapers around the country reported that Paul Thayer, the colorful Texas industrialist, was going to the Pentagon. Back in Richardson, Charles Davis noticed the picture of the man who had often stopped by to visit his neighbor, Sandy Ryno. “I wondered, when he got that job in Washington, how long it would be before his private life became public. All he’d have to do is stub his toe one time, and someone would nail him for it.”

The Investigation

A Fishing Expedition

At about eight-thirty on the morning of August 26, 1982, Bettina Lawton, an attorney in the enforcement division of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, arrived at the agency’s new office building in downtown Washington. Lawton bought a copy of the Wall Street Journal from a vending machine, picked up a cup of coffee, and took the elevator to the fourth floor. Settling behind the desk in her small, windowless office, she began studying the paper for something to investigate. She already had one case assignment, but she could easily handle another. Older, more experienced lawyers had coached her that the Journal was a good place to find new cases. Lawton was 27. She had worked at the SEC for one month.

As she scanned the Business and Finance column on the front page, the second item caught her eye. “Bendix is offering to acquire Martin Marietta for more than $1.5 billion,” it began. Lawton read the rest of the item and the article on the second page, then went looking for her boss. He was on vacation, but she caught another supervisor by the elevators. “I’d like to look into this,” she said. SEC enforcement attorneys often checked out trading in takeover targets. Her supervisor told her to go ahead.

The young lawyer then started what is known in SEC parlance as an informal investigation. In fact, it is better understood as a fishing expedition. As the Bendix–Martin Marietta fight heated up, Lawton began scrutinizing trading records for the days before the Bendix tender offer became public, looking for surges in volume that would suggest someone had been tipped. She studied minute-by-minute records for individual days, looking for large purchases in particular areas of the country or by a particular brokerage firm.

During an informal investigation, the SEC cannot issue subpoenas or force anyone except stockbrokers to provide information, but almost everyone voluntarily cooperates, rather than invite closer scrutiny. Lawton called the New York Stock Exchange, which has a staff of market analysts who routinely monitor trading, to enlist some help. She told them she was looking into the Bendix–Martin Marietta battle and asked them to keep an eye out for any peculiar transactions in the two stocks.

A month after Lawton started on the case, an analyst with the New York Stock Exchange called her back. There had been a couple of big trades a few days earlier, he told her, just before the exchange had halted trading in Bendix. She might want to take a look at it. Lawton got out the trading sheets for Wednesday, September 22. The first block purchase would prove to be a dead end. The second was Billy Bob Harris’ purchase of 38,200 shares of Bendix.

In the next few weeks the government lawyer began to zero in on the colorful Dallas stockbroker. She called A. G. Edwards headquarters and asked for order tickets to determine who had bought the stocks. She checked to see whether the trades in particular stocks had preceded any major corporate announcements. And she studied reference books to see whether there was any link between Harris, his customers, and officers of the companies whose stock they had purchased. By early December Harris’ transactions in Campbell Taggart had also caught her eye. Along with Bendix, that gave Lawton two examples of well-timed trading in 1982 alone. But was there anything more? Or was Harris just a smart investor? Lawton decided it was time for a trip to Texas to see Billy Bob in the flesh.

The Secret Informant

By the first week in January 1983, Paul and Margery Thayer had leased their home in Dallas and moved into an expensive condominium in northwest Washington. Thayer’s departure from Texas had produced quite a stir. The week before he and Margery left town, there were farewell dinners for him every night. Many of Thayer’s friends attended the swearing-in, including Billy Bob Harris, Julie Williams, Harris’ father and stepmother, and the Schroders. At a reception after the ceremony, the Thayers posed for a photograph with Harris and his friends.

Thayer quickly put his imprint on the deputy secretary’s second-floor suite. He claimed a giant carved antique desk once used by Ulysses S. Grant, and he brought in Doris Hawk as his executive assistant. He rearranged a storage and projection room in the suite to make space for his Pacer treadmill and Fitron stationary bicycle. Two or three mornings a week he began his office day at seven by changing into sweat clothes and working out for forty minutes. Then he showered in his office bathroom, put on a suit, and started in on the business of defending the free world.

In many recesses of the Pentagon, Thayer’s arrival had been eagerly awaited. The Reagan administration had sponsored a massive weapons buildup, but Weinberger and Thayer’s predecessor, Frank Carlucci, had done nothing to direct it. The secretaries of the individual military services, particularly Secretary of the Navy John Lehman, had grown more and more powerful at the expense of the office of the Defense Secretary and his deputy. In the summer before Thayer’s arrival, newspapers had uncovered a succession of horror stories about procurement abuses: the Pentagon was paying thousands for spare parts commonly available for a few dollars or even a few cents.

Thayer provided some hope. While at the Chamber of Commerce he had preached the importance of a balanced budget, declaring that even the Pentagon must join efforts to curb the red ink. He estimated that waste at the Pentagon totaled between 10 and 30 per cent of the bill for new weapons. In an administration that believed the Defense Department could do no wrong, such comments were remarkable. Thayer had announced his intention to turn things around, and he seemed to be the kind of hard-nosed guy who could do it.

But by then, Bettina Lawton’s case was the SEC’s hottest piece of business. As the investigation widened, another young attorney, Carmen Lawrence, was assigned to help Lawton. And in mid-February the commission authorized a formal investigation into trading in Bendix and Campbell Taggart. Lawton and Lawrence now had subpoena power and could take witnesses’ testimony under oath; those who lied could be charged with perjury. It had become clear that trading in the stocks—Bendix and Campbell Taggart and maybe others—was extensive. More than a dozen people were involved, and Billy Bob Harris was the broker for almost all of them. Most important, the attorneys had finally established a link between Harris and inside information. It was the most explosive secret in town: the link was Paul Thayer.

SEC attorneys say that their informal investigation had gone on for weeks without mention of Paul Thayer—that at first they had no idea of his friendship with Billy Bob Harris or his relationship with Harris’ customer Sandy Ryno. They acknowledge that a secret informant gave them valuable information, but they will not say whether the tipster provided that critical revelation. The defendants once believed the informant was a disgruntled former customer of Harris’; now they are less sure. The SEC has told defense lawyers it probably will not reveal its source even during the trial. In all probability, the identity of the informant will remain a mystery.

Whatever the source, the information that brought Paul Thayer into the case was a breakthrough. With that knowledge, Lawton and Lawrence had an advantage over those they were questioning: they knew more than their targets thought they did. After the formal investigation had been authorized, the SEC lawyers called Harris back for another interrogation; the stockbroker would go through four sessions before the investigators were through. They tried to get him to provide information about Thayer’s relationship with Ryno, but Harris, eager to hide the affair, answered as though he knew nothing about it.

Creating Misery

Paul Thayer was mad as hell. He had just received a subpoena from the SEC. Why were they bothering him? It was March, and he was just three months into his new job at the Pentagon. He had his hands full; he didn’t need any more problems. A few weeks earlier, Congressman Jack Kemp had tongue-lashed him for telling the House Budget Committee that he thought the president should delay the third installment of his tax cut. Before that, he had gone up for a test run in an F-18 fighter—a $23 million jet that McDonnell Douglas and Northrop wanted to sell to the Defense Department—and the landing gear had failed. He got down by using a backup system. He would soon have to decide how many F-18’s the Pentagon should buy.

Dealing with the bureaucracy and Congress was frustrating, and Thayer was working harder than ever before; twelve-hour days were routine. But the long-term picture looked good. He planned to stay at least two years, and already he felt he was learning how to get things done in the Pentagon. He told friends he was enjoying the job.

The SEC investigation complicated matters. His first interview with the agency lawyers lasted all day, and he was often visibly annoyed at their questions. Some of them concerned Sandy Ryno. He thought it none of their business, but he answered the questions. The SEC attorneys would interview him twice more—once all day, once for just an hour.

As the weeks rolled by, he heard more about the SEC probe from the others under investigation. It was a growing distraction, even more mercurial than the Pentagon bureaucracy. At the Pentagon he could at least give orders, even if they weren’t always followed. This SEC business was completely out of his hands. Paul Thayer was not accustomed to that feeling.

Gayle Schroder, during his sessions with the SEC, spent much time answering questions about his lending practices; they would later become a part of the government complaint. Schroder’s two small banks had loaned money to five of the other defendants, including Thayer and Harris. Williams and Rooker had borrowed $30,000 apiece to invest in Bendix; they had also borrowed $60,000 each, and Ryno $78,000, to buy stock in another company, one that was not part of the agency complaint. “The SEC made a big deal out of the fact that the girls didn’t give me financial statements,” says Schroder. “Those were what we in the business call leg loans. The people I looked out to be responsible for those loans were Paul Thayer, Billy Bob Harris, and Dr. Sharp. That’s an accommodation you made to people like that.” The trust was not misplaced. When one of the loans to Ryno for a stock purchase produced a large loss, Paul Thayer paid it off.

The friendship with Schroder also provided a discreet way for Thayer to funnel money to Sandy Ryno. On one occasion, defense attorneys say, Thayer sold a part interest in a boat docked in California; he then handed the check for the sale to Schroder and asked the banker to cash it and send the money to Ryno.

Billy Bob Harris remained characteristically charming during his succession of interviews—and solicitous of the two young women seeking to undo him. After one day of testimony in Texas, Lawton mentioned Billy Bob’s Texas, the huge Fort Worth honky-tonk, and said she was thinking of dropping by. “I know the manager of Billy Bob’s,” Harris told her. “If you want to go to Billy Bob’s, give him a call. My friend will make sure you have a good time.” Harris switched lawyers twice, finally retaining Judah Best, a Washington attorney who had represented Vice President Spiro Agnew in the plea bargaining that kept him out of jail.

Sandy Ryno, who had made $79,298 from her trading in the five stocks, did not talk to the SEC until June 29, after most of the others who later became defendants. She had been scheduled to testify a month earlier but missed the appointment. She said she was sick and didn’t want to testify.

The lengthy investigation had revealed a sharp cultural conflict between the government lawyers and the people they were investigating. The SEC attorneys thought the Texans brash and arrogant, with their own notion of moral conduct and no sense of obligation to the rules of the outside world. And they thought them sexist; with encouragement from the men, they felt, the women all had embraced the role of empty-headed ornaments. They had never met women like that. Even under interrogation, the Texans didn’t seem to take the two SEC lawyers seriously; they seemed to regard Lawton and Lawrence as young girls too inexperienced to have any business questioning their behavior.

The defendants, for their part, considered the SEC lawyers nitpickers who were hung up on regulations and niceties and unwilling to take a man’s word that he had done nothing wrong. They thought the government attorneys were out to make a name for themselves—whatever the truth and whatever the price. “They play a little different game up on the Potomac than we play down here,” says Schroder. “They like to create misery. They don’t have a case; they never had a case. They used our lives for effect in this lawsuit.”

For the SEC, the story of the defendants’ lives would indeed have great impact. Thayer was a big target and a Reagan appointee; a suit naming him would show that the enforcement staff would spare no one, and it would bring enormous attention to the war on insider trading. SEC enforcement chief John Fedders had made that his staff’s top priority from the first day of his tenure—and the emphasis produced results. In his three years as enforcement chief, Fedders has brought more than half of the insider trading cases filed in the SEC’s fifty-year history.