This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

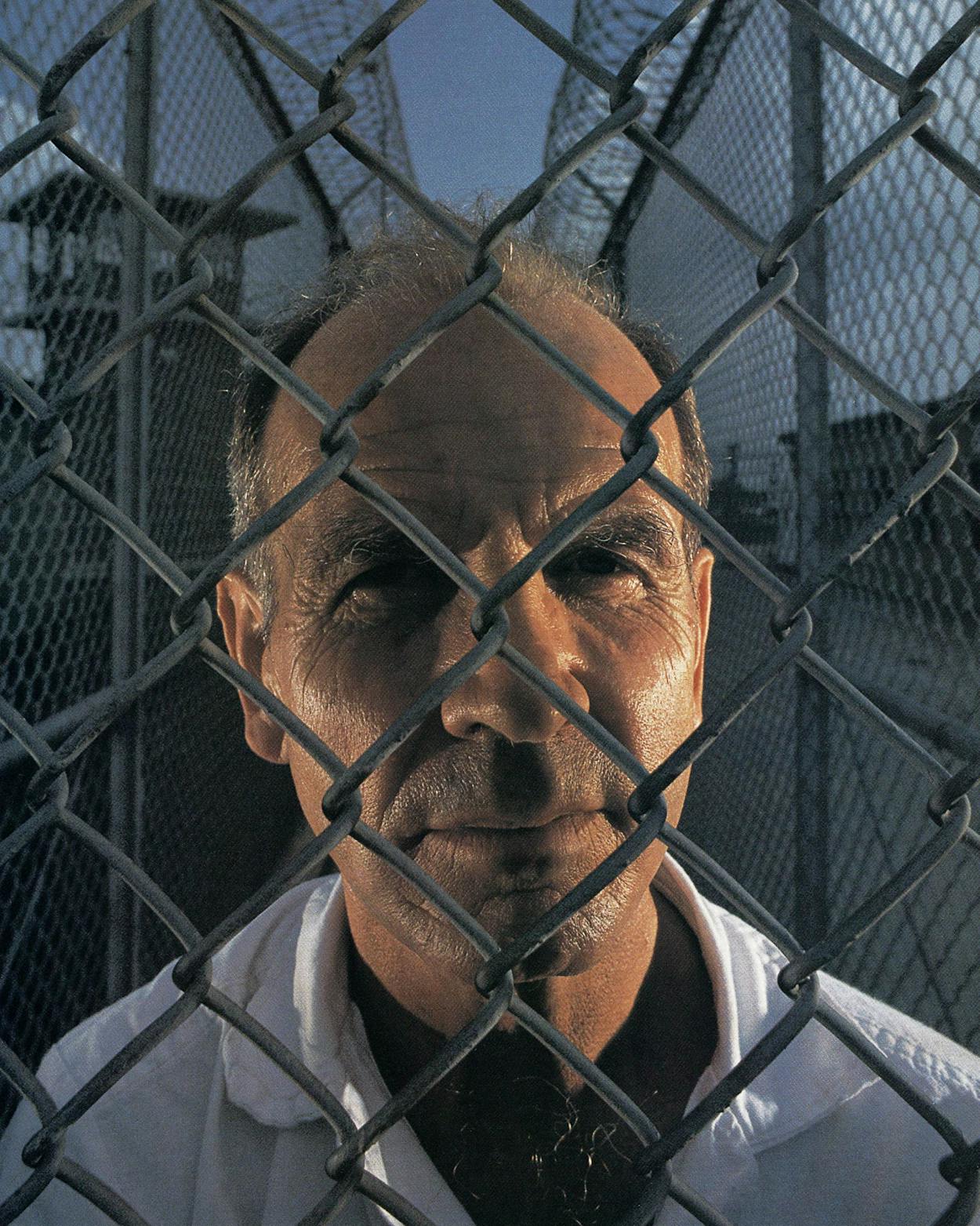

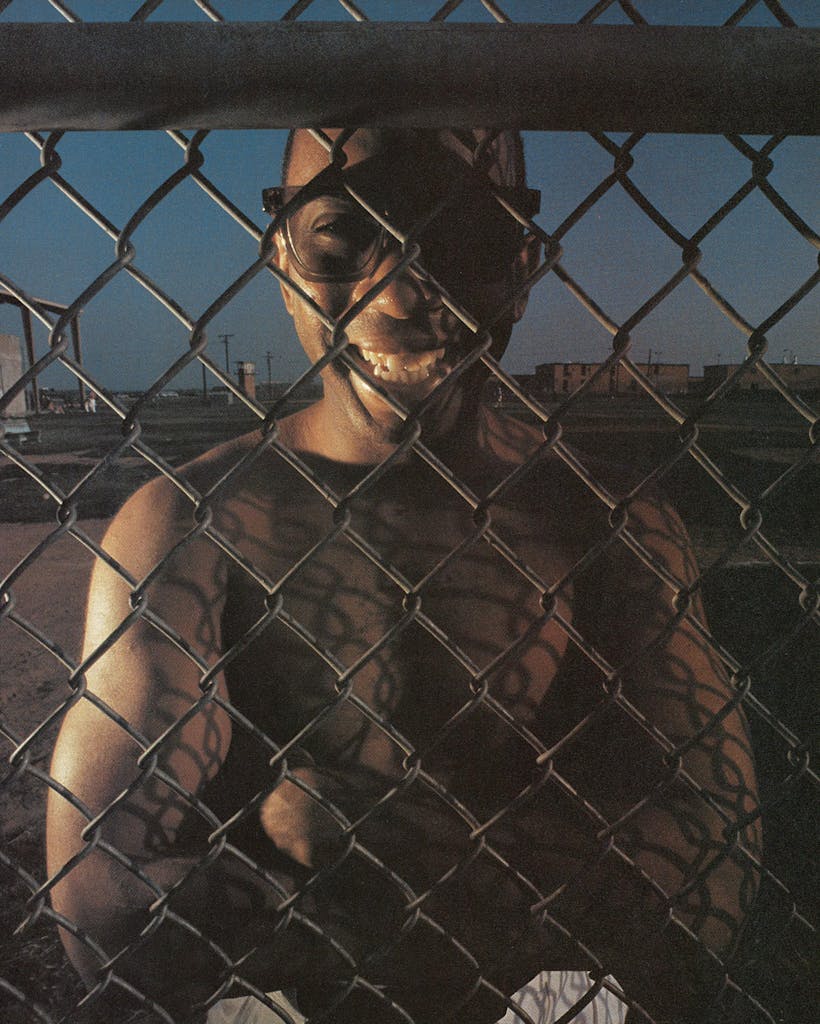

At the robbery division of Austin’s police headquarters is a bulletin board labeled the “Haul of Honor,” on which are displayed photographs of captured criminals. The thought that they could be anything but criminals causes the imagination to balk. Yet among the photographs are a handful of portraits that leave one wondering what went wrong. There is a photograph of what looks like an attractive young couple labeled “Mr. and Mrs.” They are, in fact, two gay male bank robbers who decided to expand into Texas after committing a series of holdups on the West Coast. Then there are the pictures of the two men responsible for what came to be known as the Gold Porsche Bank Robberies. One is a snapshot of a middle-aged white businessman. It is decorated with Boy Scout insignia and is captioned “All American Man.” The other is a Polaroid of a young black man sitting in a Taco Bell, a spontaneous smile spread across his face. His caption reads: “Give him Talk-O-Bell.’ He’ll talk.”

The Gold Porsche Bank Robberies (a gold Porsche was the getaway car for two of the holdups; the third was actually a blue Chrysler bank robbery) were neither the most heinous nor the longest-running of Texas crime sprees. What the robberies were was a most unusual response to the bust, committed by the most unlikely of criminals, whose thinking came down to this: Why declare bankruptcy when you can rob banks?

Like thousands of other Texans in 1987, Howard Pharr was facing a personal financial crisis. Howard is a trim man of 56 whose strong cleft chin gives distinction to his pleasant features. He was born in Waco, and after attending Baylor, he joined the Air Force, reaching the rank of first lieutenant. (“I got out just before Vietnam. I feel I missed something,” he says.) In the early seventies he was a coordinator for the state’s drug-abuse program. He possesses the sincere smile and confident handshake of the born salesman—for the past ten years, he has been selling cars in Austin. His wife, Sally, owns a vintage-clothing store, and they have a grown son and daughter. When his son was little, Howard was a Boy Scout troop leader. “In six years we produced eighteen Eagle Scouts,” he boasts.

Howard had worked at a number of automobile showrooms. Car salesmen are the serial monogamists of the business world; when the magic is gone they move on to the next dealership. In 1986 he decided to strike out with a partner, retailing and wholesaling used cars. For a while things were good—good enough for them to be featured that year in a Texas Monthly story about businesses that were making it in the bust. Then Howard and his partner had a falling-out, and Howard went to work for himself. It was tough going, and that, combined with a five-figure bill owed the IRS, soon made it clear that he couldn’t simply work himself out of his debts.

Howard decided to enter criminality cautiously, however. For his first foray he would stick with automobiles, a business he knew. In November 1987 he got in touch with a West Coast car dealer of sorts—the sort being stolen cars. The dealer knew of a young man in Austin, a friend of a friend, who was having hard times of his own and might be able to help Howard in his new endeavor. Enter Kevin Hutchinson.

Howard was immediately impressed. “Kevin was articulate, intelligent, and he presented himself well,” he recalls.

Kevin Hutchinson is all that. He is also the possessor of a variety of ambitions, all of them big, which at every turn have been thwarted by a combination of bad luck and lack of discipline. A slight man of 28, he sometimes imagines being the next Eddie Murphy, he sometimes sees himself as a nightclub impresario. He was raised in Austin; his grandmother is a maid, his mother is a professional with a state agency. After high school, he had a series of jobs—some of which brought him brushing against the show-business success for which he longed. For several years he worked at the nightclub Phases, where he started out doing maintenance and eventually got a chance to sit in the disc jockey’s booth. Then the club folded. He also had a stint on the air at a local radio station. But Kevin had a serious marijuana habit, which began to interfere with his work. The station manager fired him. He dabbled at computer school, got part-time jobs at downtown hotels, and started taking cocaine. “I was having a lot of problems with my girlfriend. I use drugs to hurt myself,” he says. Soon the cost of drugs outstripped his income, and he got arrested in Dallas for shoplifting.

Kevin found himself starting over at Austin’s swank Metropolitan Club—a private dining and exercise facility, where he made his way up from busboy to lunch-time deli manager. But his career in the hospitality industry was shattered by mayonnaise. Even though he was advised repeatedly that the city’s elite wanted to eat light at lunch, he continued to serve calorie-laden, mayonnaise-drenched salads. Soon he was out of work again.

Sitting in his green prison fatigues, with ill-fitting orange flip-flops on his feet, he has had time to think of the decisions he has made. “Life is a bunch of never-ending mistakes you have to go through,” he says. “I was desperate and compulsively ignorant. Howard put suggestions into my head like a program in a computer. If I could turn time around, I’d surely put Howard in the wind.”

Hot Cars

Howard’s first suggestion involved a Datsun 300 ZX. They would steal it, and Kevin would drive it to the West Coast dealer for a $500 payoff. Howard concedes only that he talked with Kevin about such a proposition. But Kevin vividly recalls his adventure in the hot-car trade. “Howard asked me if I had a license. I said yes, even though I didn’t, because I didn’t want to lose the opportunity to drive a gold 300 ZX to Los Angeles,” he says.

Howard applied his methodical nature and business connections to his new enterprise. Early in the day he went to the lot with the Datsun and took the car for a short drive to try it out, stopping to have a duplicate key made. After the lot closed, he and Kevin sneaked back, and Kevin took the car for a permanent test drive. “I did a hundred and twenty all the way to El Paso,” Kevin says. “I was worrying about lawmen all the way out there, but there was nothing but sun and coyotes.”

Los Angeles did not disappoint. “The first place I went was Hollywood and Vine. I put my hands into Eddie Murphy’s handprints at Grauman’s. I have the ambition to be a singer or comedian, and now I know where things are.” Kevin’s ambitions as a car thief were running into trouble, however. The dealer on the other end said he didn’t have the $500. Kevin stayed for several days, having the vacation of his life while waiting for the money. It never came through, but the dealer finally put him on a plane back to Austin. Howard met him at the airport and told Kevin he had sent four cars to Los Angeles but got paid only $100 a car—at that rate Howard might as well have sold them legitimately. The two men saw they needed a new approach. As Kevin recalls, “Howard and I decided to go to work for ourselves.”

The partners resolved to keep their new business Texas-based. Howard arranged for Kevin to take a stolen maroon Corvette to Dallas, where a customer was waiting. Howard instructed Kevin to drive to Temple, stay the night, and continue to Dallas the next morning, when the traffic would make the car less conspicuous. Temple was not exactly L.A. “I decided to look for a woman,” Kevin says. “I spent all night, but I never found one.” In the morning he pulled into the customer’s driveway. The customer and his wife greeted Kevin at the door, but the customer took that inopportune moment to explain to his spouse that they were about to become the owners of a stolen vehicle. The wife had a predictable response. “She started cursing me out and told me to get out of her driveway,” says Kevin. The chastened husband gave Kevin $100 for his troubles. Kevin spent the day in Dallas, then headed back to Austin.

Near Waxahachie, about one-thirty in the morning, Kevin stopped at a convenience store for a cup of coffee. As soon as he entered the premises he realized this just wasn’t his night. “When I walked in, a white police officer was there,” he says. Kevin said hello and tried to act nonchalant, but he noted with alarm that when the officer left he cruised very slowly past the Corvette.

Kevin got as far as Hillsboro, where a squad car was waiting for him. Soon police cars were coming from every direction. A routine check of the Corvette’s license plate had revealed that the car was stolen. Kevin spent the night in custody, then in the morning he was transferred to the Travis County jail. From there he called Howard Pharr.

The record in the case can be read as a harbinger of their skill as a crime duo. According to the arrest warrant, the car had been stolen from the car lot of Howard Pharr. “Howard Pharr does wish to file charges on Kevin Hutchinson,” says the warrant. On Kevin Hutchinson’s statement, in the space for “Family or Permanent Contact,” after the name of his grandmother, is the name Howard Pharr. And while Howard was telling police he wanted to press charges against Kevin, he was paying Kevin’s bail and attorney fees. The district attorney’s office ultimately decided the best approach to the entire matter would be to dismiss it and pretend it never happened.

“Howard was pissed,” Kevin says today of the fiasco. Worse, they had even less money than when they started. Trying again seemed like the only logical answer. So Howard gave Kevin $250 to finance a trip to Laredo, where he was supposed to make his own connection on the border to fence the stolen car he drove down. “Laredo was the most depressing thing I’d ever seen,” Kevin recalls from jail. “There were ladies sitting on the cement with four or five babies, with a cup in their hand. Even the policemen looked pitiful. I called Howard and said, ‘These people can’t buy a car; these people are desperate.’ I turned around and drove home. At that point Howard told me I had spent too much of his money.”

Acting the Part

It was mid-December, and Howard prudently concluded there was no money in stolen cars. He did, however, know one place where the money was. “Howard says to me, ‘I’ve been checking out a few banks,’ ” Kevin remembers. “When I heard that, I said to myself, ‘Banks! This white man has lost his mind.’ ”

Howard concedes that that is a possible explanation for his decision. “My lawyer talked to a psychiatrist who said I flipped my wig,” he says. But he also offers a more prosaic reason for entering the world of first-degree felony: “I wanted enough money for living expenses, to cover my debts.”

Although Kevin initially rejected Howard’s suggestion, he soon found it was another one of those ideas that played in his head like a computer program. “I thought, this man’s got a nice business, a nice house, a nice family. He’s putting it all on the line. All I’ve got is time, and I still don’t have my five hundred dollars. They’ve already got me for car theft—what else do I have to lose?

“After the arrest, when I got in jail, the brothers all laughed at me. They said, ‘You should have run from this peckerwood.’ ”

On December 14, 1987, Howard Pharr and Kevin Hutchinson robbed their first bank. Howard staked out the Bright Banc at 5730 Burnet Road, in a strip shopping center within a mile of his suburban North Austin home. He had the perfect getaway car for the job: a gold Porsche 928 that was on his lot under consignment. Howard felt that what the car lacked in anonymity, it made up for in speed. About five in the afternoon Kevin met Howard at the car lot.

Both men prepared themselves mentally for the task ahead, using a sort of psychic visualization to ensure their success. Kevin called on his show-business ambitions: “I’ve been an actor all my life. I decided to act the part of a bank robber.” Howard imagined he was back in the Air Force. “It was almost like a flight mission,” he says. Howard was the mission commander. He gave Kevin a nine-millimeter handgun, purposely left unloaded. As a disguise, he stuffed Kevin’s mouth with toilet paper. (“I don’t know where he came up with that one,” Kevin says.) His planning even extended to the color of the ink—red—on the holdup note that he wrote out on an index card for Kevin to hand to the teller. “Red ink is attention-getting,” Howard explains. Kevin had attended to the wardrobe department. He got a black knit cap and a black leather jacket to help him look the part he was about to play.

Just before the six o’clock closing, Howard and Kevin drove up to the bank. Kevin’s role was brief and profitable. In less than five minutes he was back in the Porsche with a bag full of money.

They were both exhilarated. Howard dropped Kevin off, and they agreed to split the take later. Then he drove back to the lot and returned the Porsche—“I put it on the point, that’s the corner where the best car goes.” The take was about $3,500; never again would they consider trying to sell hot cars on the border. Kevin was overwhelmed at the return on a few minutes’ effort. “My heart just about died. It was more money than I ever saw in my life.”

After distributing much of his share among his family, Kevin decided to celebrate, at which point his usual run of bad luck returned. For one thing, he wasn’t as good as Howard at giving orders. Kevin gave a friend a few hundred dollars and told him to get him a room at a classy hotel and some drugs. “He gets a room at a Motel Six. A Motel Six! ” Kevin says, still outraged. The drug that was purchased was crack. Neither Kevin nor the woman he brought along for the night had ever taken the drug before. “We both spent the night throwing up all over the place,” he says. Still, the party went on for three days—at the end of which the money was gone.

Howard also went through the money almost immediately, although for more mundane expenses. Given his bills, $1,700 was hardly the equivalent of an FDIC bailout. After Kevin recovered from his party, he called Howard to discuss their financial situation. Howard had an idea. It turned out there was another nice little Bright Banc on Research Boulevard, again only minutes from his house. On December 18 Kevin arrived at the dealership (he had exchanged his cap for a ski mask), Howard rolled the Porsche off the lot, and they robbed another bank. While Howard waited around back, a police car on a routine patrol drove by—Howard held his breath, and it passed just before Kevin came out with the money. The robbery was as successful as the first—they got about $3,500.

That night, as Kevin lay relaxing in front of his TV, his attention was caught by a teaser for the news: “Bank robbers use Porsche as getaway car.” The bad news was that someone had seen the two of them as they drove away. The good news was that the police had little information other than the make of the vehicle.

Indelible Ink

That they had been spotted but had still gotten away with it only seemed to add to Howard’s sense of adventure. He saw the two of them as a sort of Bonnie and Clyde of the eighties. He confided to Kevin his plan to drive all over Central Texas, holding up small, unprotected banks. Howard’s partner managed to veto that suggestion. “I said to him that in Williamson County they’ve still got holes in the floor to hang people,” Kevin recalls. So for their third robbery, on December 21, Howard again decided to stay close to home, choosing the First Federal Savings Bank on Burnet Road. Howard knew it well: the bank was so convenient to his house that at one time he had had an account there. His one concession to their having been spotted was to leave the Porsche on the lot. This time he took a less glamorous Chrysler.

For teller Ida Shields, a forthright woman with a gray bouffant, it was her second robbery of the year. The first one had taken place that summer, and the robber had been agitated and threatening. In spite of the ski mask and gun, she remembers Kevin Hutchinson as being wholly different. “He was very kind-talking. I know this sounds funny, but he was almost sweet. He didn’t seem nervous; it seemed to me that it was like a game for him.” Kevin’s polite request for money sent the tellers, all women, scurrying to their cash drawers. Everything was going smoothly, except for one brief moment of peril—when Shannon Ruby, following Kevin’s orders, went to get the money.

Shannon Ruby is a tall, extremely attractive woman. On the day of the robbery she was wearing a pleated silk dress. As she walked toward the drawer, Kevin recalls, the silken pleats caressed her thighs, causing him to momentarily lose his composure. Even Ida Shields noticed something was wrong with the robber. “He was just watching Shannon and the gun was drooping at his side,” she recalls. When Shannon pulled open the cash drawer, Kevin quickly came to, reminded of his purpose. “It was all fifties and hundreds. I thought, ‘We’ve hit the jackpot.’ ” His departure was slowed by his need to stop and pick up the wads of bills that were tumbling out of the bag. Just before he left, he turned to have one more word with the tellers. “Thank you, ladies,” he said.

It had been the partners’ most successful robbery of all—more than $8,000. They drove around the corner to Howard’s house. Kevin took a few thousand for spending money and stashed the rest of it, as well as the gun and the ski mask and his jacket, in a corner of the garage. Kevin went out to celebrate, and Howard went back to his car lot.

Shortly after Howard returned to work he got a disturbing call from a neighbor. There were about fifteen police cars and more than that number of officers in flak jackets surrounding Howard’s house, the neighbor reported, and a STAR Flight helicopter was hovering overhead.

Howard didn’t know it at the time, but when the pair robbed First Federal Savings they picked up more than just the money—they also picked up a radio transmitter.

The police at first believed that the robber might be inside, holding the family that lived there hostage. Lieutenant John Stewart, a large, taciturn man, was the first officer to enter the house. In case he was met with a fusillade, the other policemen were poised behind their cars, assault rifles ready. They found the house empty. In the garage they located the money and Kevin’s effects in the corner. As the lieutenant stood outside, puzzling over the situation, he noticed that a well-dressed middle-aged man appeared to be trying to sneak into the house. It was Howard Pharr. Testifying in court, Stewart said that Howard seemed neither surprised nor disturbed by the scene. “Is this a typical reaction of a person coming home and finding twenty officers outside his house?” asked assistant district attorney Ashton Cumberbatch, Jr. “No, sir, it’s not,” Stewart replied.

Howard later justified his behavior as being perfectly normal. “I’m not the kind of person who panics,” he says. “I come home and see police around my house, it’s like”—he shrugs—“what’s this?” Howard agreed to go to police headquarters for questioning. “I claimed shock and innocence,” he says. But as the questions progressed, he decided a lawyer should speak for him.

In the meantime, Kevin Hutchinson, oblivious to the events, was enjoying his version of the high life. “After I picked up my car I stopped for gas and gave the attendant a twenty and told him to keep the change. I gave four hundred dollars to my grandmother, five hundred to my lady. I bought a new sweater, an L.A. Lakers shirt, a baseball cap, and an eight ball of cocaine.

“That night I turn on the TV. I have new clothes on, I feel like a million bucks, and then I hear on the news that the police have captured one bank robber and are looking for another. On the TV I recognize Howard’s fence, I recognize his driveway. Then the camera goes on the money bag. And then it goes on my jacket. And then I say, I’m f—ed.”

As Kevin looked at the televised image of his Perry Ellis rain jacket lying on Howard Pharr’s driveway, he knew it would not take ace detective work to locate the second suspect. For most of his life, Kevin has lived with his grandmother. It is her habit to write with indelible ink on all of his clothes his name, address, and phone number.

The next day Kevin called Howard, who had not yet been charged with the robberies. Howard was in tears, complaining that the police had ripped apart his home. He told Kevin to flee. When Kevin said that he thought such an action might result in his getting shot in the back by the police, Howard turned cold and advised him to get a lawyer. Instead, Kevin confessed his crimes to his younger brother, a college student. “I said, ‘Junior, you’re not going to believe this. I just robbed three banks.’ He just jumps up and runs out of the house. He comes back in a little while, huffing and puffing, and he says he’s got an officer outside who wants to talk to me,” Kevin says.

Kevin agreed to talk, but he wanted something in return: Knowing all too well the quality of the food at the city jail, he asked to be taken to the restaurant of his choice. The officer agreed. “I wanted to go to Taco Bell, because I wanted to be fed well,” Kevin says.

Built on Trust

At first Kevin hesitated to do more than turn himself in. “Most criminal relationships are built on trust. I didn’t want to sell Howard out.” But then the police offered Kevin a deal. If he confessed, he would be charged with only one robbery. The police emphasized that Kevin really didn’t owe Howard anything. “Your ass is on the line,” Kevin says one officer pointed out. His argument made sense to Kevin.

On December 29, Howard Pharr, the former Boy Scout leader, was charged on three counts of aggravated robbery with a deadly weapon. Being convicted of such a crime comes with a jail term ranging from 5 to 99 years. In an article about the robbery in the Austin American-Statesman, Howard’s son conveyed the family’s shock, describing his father as the “all-American man.”

Kevin was charged as well, though only for one count. The former partners stood next to each other without speaking. Howard was angry at what he perceived as Kevin’s betrayal. “Kevin’s a snitch. I thought young black people were better trained,” Howard observes now. Kevin was annoyed as well: “There are all these TV cameras, and my hair was nappy.” He was also sick of seeing Howard portrayed as a person of fine character. “It didn’t feel too good to read that he’s all-American. He’s just another businessman whose business was failing, and he tried to pick it up any way he could,” Kevin says.

Even though Howard had masterminded the robberies, choosing the locations and supplying the weapon and the vehicle, Howard’s bail was set at $25,000 for each charge. Kevin’s was $50,000. The inequities of the system’s treatment of the white criminal versus the black were somewhat ameliorated by the fact that Howard, because he was charged with all three robberies, had to meet the bail three times. But that was soon done. Prominent Austin furniture dealer Les Gage, who knew Howard from their sons’ Boy Scout days, posted his bond. Kevin’s family, however, could not come up with the $10,000 necessary to secure his release. The state would have to put him up until his court date.

For Kevin, his arrest was just another of the never-ending mistakes that add up to one’s life. He did not have either the psychological or the financial resources to proclaim his innocence. His court-appointed attorney, Patrick Ganne, advised Kevin to plead guilty. Ganne hoped to use his client’s cooperation to bargain for a reduced sentence. Howard, on the other hand, retained former Travis County district attorney now criminal lawyer Robert O. Smith, as his counsel. Howard entered a plea of not guilty. It seemed a reasonable gamble: he was an upstanding businessman with no prior record, no one had actually seen him at any of the bank robberies, and there was a question as to whether the police search of his home had been conducted properly. He returned to his car lot to wait.

Wishful Thinking

Kevin was released in March 1988. Because he was the sole witness to Howard’s participation in the robberies, the DA’s office thought he would be a more cooperative one if he wasn’t coming to testify from a jail cell. He would not have to start serving his ten-year sentence until Howard’s case was resolved. Because of a nearly endless series of postponements of Howard’s trial, Kevin was free for the rest of the year. It was not a time of which fond memories are made. Kevin married his girlfriend, but the marriage broke up three weeks later. He had several odd jobs, doing yard work and cleaning pools, but felt guilty because he was a financial drain on his family and a social pariah. Since it was taking so long to resolve Howard’s case, toward the end of the year a certain sense of suspension set in. Kevin got a job at the Spaghetti Warehouse as a busboy and had dreams of working himself up to waiter (“I’m a great waiter”). He even began hoping that perhaps the prosecutors would decide he didn’t have to go to jail after all.

If anything, Howard Pharr was enjoying his freedom even less than Kevin Hutchinson. His family was suffering emotionally and financially as a result of his crimes; soon the Pharrs lost their house. Howard’s indictment did nothing to improve the economic condition of his auto business, with one exception. The publicity about the gold Porsche robberies did bring in a buyer for the car. Later that summer there was a little confusion about the title to another car that Howard had sold. The confusion rested with the fact that Howard didn’t have title, so he went back to jail on a new felony charge. This time his stay was for two weeks. As usual, he puts the best face on things. “The conditions were decent. It was sort of a basic-training atmosphere.” At that point Robert Smith, Howard’s attorney, withdrew from the case, and Howard too found himself with a court-appointed lawyer, Charles Hineman. Hineman had one of those it’s-a-small-world caseloads: he also ended up representing Kevin’s estranged wife in their divorce proceeding.

Howard Pharr too indulged in his own wishful thinking about his fate. As the holidays approached, his spirits were raised—juries would surely be more forgiving the closer it got to Christmas, he observed. Since almost everyone charged with a violent crime is found guilty anyway, actually trying such a case is viewed by the state as a huge waste of time. The efficient thing to do is to arrive at a plea bargain. But negotiations with Howard were at an impasse. The district attorney’s first offer of 40 years in exchange for a guilty plea seemed to present Howard with nothing except free room and board during his retirement years. Then for months the state refused to go lower than 25 years. Again Howard balked. The assistant district attorney in charge of the case, Kent Anschutz, was sure he could get a conviction if the case went to trial. Yet there was a nagging doubt: What would a jury of financially strapped Texans think about the businessman and Boy Scout leader turned bank robber? Maybe they would be outraged. But maybe, Anschutz worried, they would be sympathetic to this roguish response to the bust.

Attorney Hineman’s leverage came from the constitutional questions raised over the search of Howard’s home. He thought that even if they went to trial and lost, they had a fair shot at a reversal on appeal. In the end a deal was struck. On November 29, 1988, Howard Pharr pleaded guilty to three counts of armed robbery. He was sentenced to 12 years at the Texas Department of Corrections.

A Working Vacation

One consequence of Howard’s conviction was the end to Kevin Hutchinson’s dream of freedom. Because of the comparative lightness of Howard’s sentence, Patrick Ganne was able to get the state to reduce Kevin’s charge from aggravated robbery to simple robbery. In the rough calculations of justice, the state recognized Kevin’s characterization that he was like a computer that Howard had programmed. His ten-year sentence meant that Kevin could be eligible for parole after serving ten months. After all his waiting, Kevin was eager to start. “It was an adventure,” he says of the robberies, “but I’m going to put it behind me. I’m going to put drugs behind me. I’m going to do the time for the crime.”

Howard Pharr wasn’t quite so ready. A group of about a dozen friends organized a letter-writing campaign on his behalf to ask the judge that he be put on probation. The letters came from Air Force buddies, business associates, neighbors, even former members of his Boy Scout troop. Each movingly recounted examples of Howard’s character and friendship. Each said the robberies were a bizarre aberration that would never be repeated. Howard thought he would be a good candidate for a prison alternative: wearing an electronic device that monitored his whereabouts. “It costs twenty-five thousand dollars a year to put a man in prison; it’s cheaper to go to Harvard,” he points out. “I could generate tax money for the state by working. I feel bad about that—I used to work for the state.” Because Howard had pleaded guilty to a crime involving a deadly weapon, however, the judge was required to impose jail time. Howard would have to do three years before he would be eligible for parole.

Howard was scheduled to begin his sentence on January 3, 1989. Around dawn on December 31, a police officer in Williamson County pulled over the driver of an automobile-transport trailer for a routine violation: a taillight was out. Closer inspection revealed that the driver, Howard Pharr, was at the wheel of a stolen vehicle. The word was that it was Howard’s desperate attempt to get some cash together for his wife. Howard spent New Year’s Eve in jail.

Both Howard Pharr and Kevin Hutchinson planned to use their incarceration as a sort of working sabbatical. Howard looked forward to taking advantage of the adult-education classes offered. He also expected to be on the top of the cultural heap at what he calls the iron-bar motel. “An armed robber gets respect in criminal circles. Rapists, wife beaters, snitches are not respected,” he says.

Kevin hoped to hone his show-business skills. “I’m trying out my comedy here,” Kevin said while still in the Travis County jail. It was succeeding with a captive audience. “I’m getting laughs out of things I didn’t think I would get laughs out of.”

After being processed through the diagnostic unit at Huntsville in mid-March, both Kevin and Howard were sent to do their time at minimum-security prisons. Howard is working as a clerk in the education department of the Pack 1 Unit in Navasota and studying business and computer programming. He lives in a supervised dormitory with about sixty other prisoners. He is, according to Warden Bobby Morgan, “a good bit older than the average.”

Kevin works in the canning plant at the Ramsey 3 Unit in Rosharon. It is not the sort of career move the next Eddie Murphy would choose, but there was a glimmer that maybe his never-ending mistakes were behind him. On April 6, because of his good behavior, Kevin Hutchinson was promoted to trusty.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Austin