Dana Blair, the director of the Kilgore College Rangerettes, stood on the sideline at AT&T Stadium, in Arlington, on January 2, 2017, and surveilled the field like a hawk, her blue eyes in a squint and her lips pursed in concentration. She was watching her girls—members of the nation’s most prestigious drill team—perform a pregame routine at the Cotton Bowl Classic, and every movement had to be perfect. Their high kicks, leaps, and arm motions needed to be fast and precise, requiring such uniformity that even a first-time observer would notice a mistake.

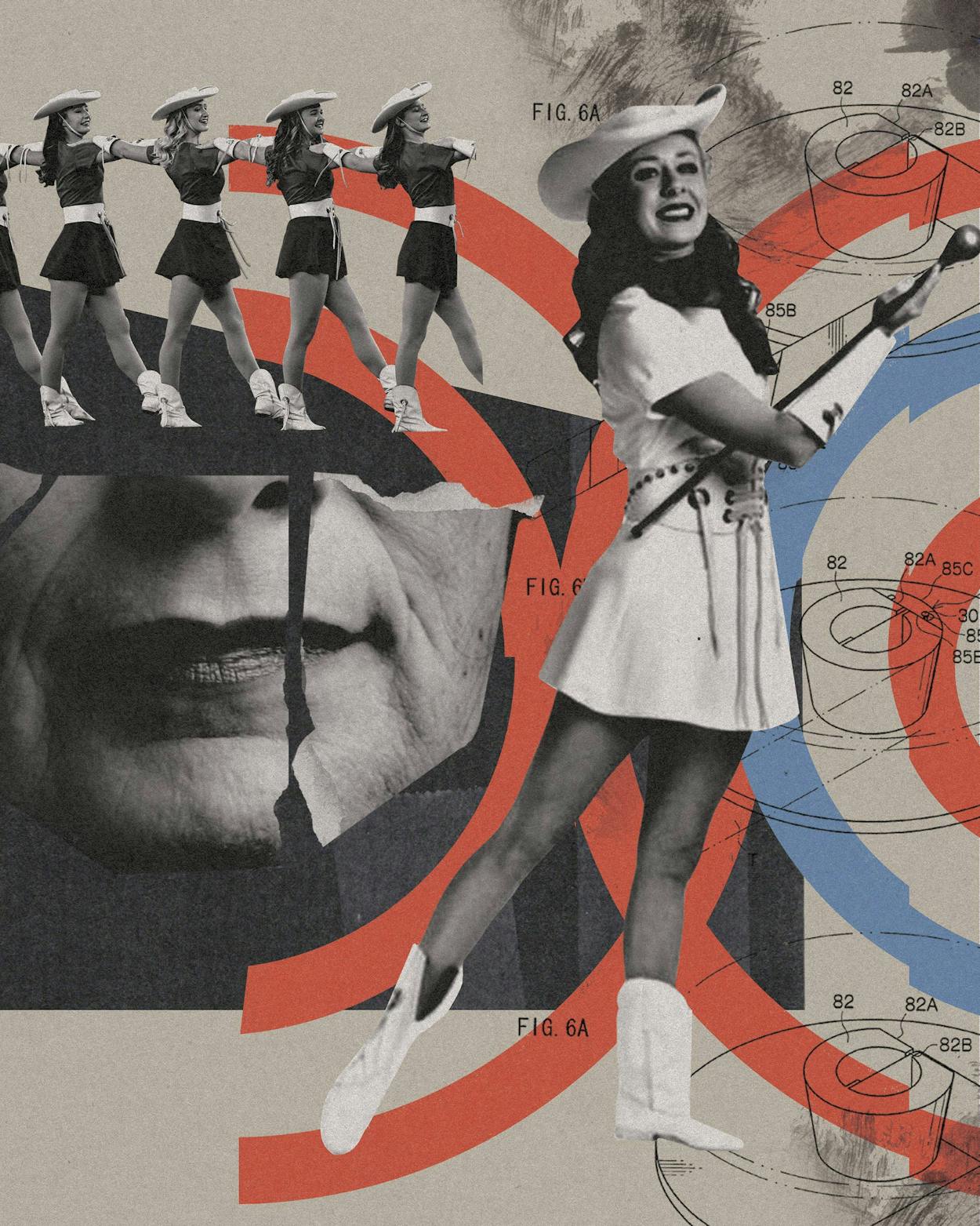

Blair did this every year, but this show had a special significance, as her only child, Alexa, was dancing at the Cotton Bowl for the first time. After watching from the stands for years, the redheaded nineteen-year-old was now dressed in the same basic uniform Rangerettes had been wearing since the group’s formation in 1940: white boots, royal blue miniskirt, white leather belt, white wrist gauntlets, candy-apple-red shirt, and white cowboy hat. The iconic look was rounded out by curled, shoulder-length hair and bright red lipstick. The performers were so similar that from a distance, their own parents might struggle to tell them apart. Dana, of course, knew where Alexa was—along with the position of every other Rangerette—the way an astronomer might point to the sky on a cloudy night and identify any star in the firmament.

Dana also understood what this day meant to her team. She had first performed at the Cotton Bowl in 1982, five years before she became the organization’s choreographer and assistant director, and eleven years before she was named director. Since the Rangerettes’ 1949 Cotton Bowl debut, their nationally televised routines have been one of the troupe’s signature appearances. The shared notion, Dana said, was, “One of my legs would have to be missing for me to not go out there. That’s how all Rangerettes are.”

Dana had always been careful not to push her daughter toward joining the group, but once Alexa began her freshman year at Longview High School, drill team cemented its hold on her. The teenager committed to doing whatever was necessary to make the squad—stretching her hamstrings and hip flexors with splits, strengthening her leg and core muscles, practicing leaps until they looked effortless. Once she made the high school roster, she was hooked. Four years of workout sessions and intensive summer camps later, she earned her spot with the Rangerettes in the summer of 2016.

Alexa’s life changed immediately. Freshman Rangerettes aren’t allowed to speak during practice except to say, “Yes, ma’am, thank you, Ms. [last name].” Save for blinking, breathing, and doing whatever they’re told, they’re expected to stand still with perfect posture, look straight ahead, and smile. It doesn’t matter if sweat is pouring down their faces, if they have an itch, if they feel as if they’re about to collapse. A few mornings a week, they do cardio and strength training, followed by an advanced jazz-dance class. After the school day, they head to the field to spend hours practicing as many as seven hundred high kicks, even in the scorching East Texas heat. “That’s definitely the most fit I have ever been in my entire life,” Alexa said.

At the Cotton Bowl, before the troupe returned to the field at halftime, Alexa felt a jolt of adrenaline when the PA announcement for their appearance reverberated through the stands. The second routine was trickier than the pregame act; the girls started in formation, each standing behind a folded white chair, head bowed. Then, sometimes in unison and sometimes in waves, they completed a series of leaps and kicks and poses, up and down off the chairs. At one point, Alexa had to run with her chair from the fourth line to the front, hitting her mark on the beat. For their grand finale, the girls stood on the chairs and kicked waist-high, never wobbling, before each dancer tucked her left leg behind the teammate to her left and slowly bowed.

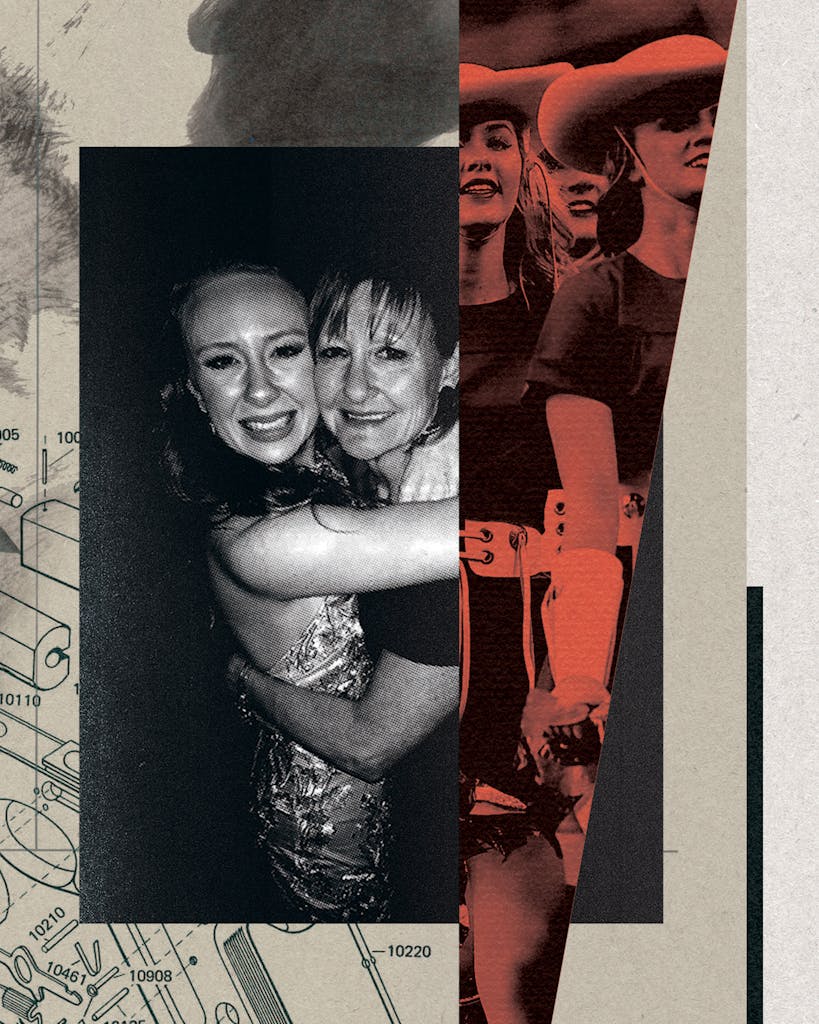

Watching Alexa, Dana remained professional at first. Was she polished? Was she ready? Check, check. She was on the mark; she made no mistakes; she was a Rangerette. “She was good enough,” Dana said, “but she had to work really hard to get to that level.” Only after that came the mother’s pride.

What few in the stands knew was that Alexa had overcome much more than an exhausting practice regimen to be there that day. If they’d been close enough to see, they might have noticed that her eyes were bloodshot and her neck was bruised. Her fellow Rangerettes knew how she’d received those injuries, but none of them dwelled on it that day, and neither did Alexa. They were focused on keeping the mood upbeat.

But all of them understood the gravity of what had happened. Four nights before the big day, Alexa and her mother had been kidnapped at gunpoint. They were lucky to have escaped—and lucky to be alive.

It was like something out of a bad movie,” Kilgore mayor Ronnie Spradlin said. Spradlin, trim and tan with bright white teeth, sat eating coffee ice cream in the front window of a shop called Kilgore Mercantile and Music one 90-degree afternoon last summer. Spradlin had been a Rangerette manager in his youth. Even if he hadn’t served as the town’s mayor since 2010, many locals would know him as a lifelong Kilgore resident and for his connection to the Rangerettes.

Between spoonfuls of ice cream, he recalled the day in late 2016 when one of his constituents, a woman with no previous criminal history named Nancy Motes, kidnapped Dana and Alexa Blair. “I don’t know if you’ve heard the story about why Nancy Motes was angry, but it’s very convoluted,” Spradlin said.

“Convoluted” might be an understatement. Those without direct knowledge of the crime assumed it was some kind of retaliation against the Rangerettes, given the Blairs’ involvement with the troupe. But to the best of anyone’s knowledge, Motes and her family never had much interest in the organization.

Not that they could have been unaware of the Rangerettes. This historic oil town of 14,000, after all, is the motherland of precision dance. The Rangerettes were the brainchild of the late Gussie Nell Davis, a figure whose legacy is venerated in Kilgore like a benevolent general in high heels and higher hair. Davis created the troupe in 1940, when the former high school physical education teacher came to Kilgore College. Charged with putting on a halftime show that would keep football fans in their seats, she envisioned a dance line that looked a bit like a hall of mirrors—young women, smiling and moving as one, virtually indistinguishable.

The Rangerettes don’t cheer. They don’t do stunts, nor do they tumble, and they certainly don’t execute moves that might offend your grandparents’ sensibilities. Rather, the group of seventy-some women execute a highly technical, athletically demanding style of dance that features jump-splits and Rockettes-style kick lines.

In Davis’s vision, the Rangerettes signified a way of life, her idea of perfection. Davis stressed manners, discipline, endurance, appearance, and physical strength, and she could be unrelenting. “By the time I was through with [my girls] they were scared to death to act like heathens,” she once said. Her most popular saying was “Beauty knows no pain,” and it became the Rangerettes’ motto.

The Rangerettes don’t cheer. They don’t do stunts, nor do they tumble, and they certainly don’t execute moves that might offend your grandparents’ sensibilities.

It wasn’t long before schools throughout Texas were fielding their own drill teams, but Kilgore’s version has remained iconic. Within a few years, the Rangerettes had become synonymous with the town, its proudest export since the thirties oil boom, and the group eventually became ambassadors for Texas and the entire country, performing for presidents, foreign dignitaries, and spectators at the annual Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, in New York City.

Thanks to Davis, Kilgore College, a two-year institution with a current enrollment of about five thousand students, has become the West Point of precision dance. And so, each summer, young women from all over descend upon East Texas for a week of intense tryouts. To make the team, they must show skill, stamina, and dedication. Once they’re accepted, they live in the Rangerettes’ $3.5 million dormitory, where framed photos of Davis and other notable alumni decorate the halls alongside Rangerette dolls, statuettes, and mounted dance uniforms. Kilgore’s Rangerette Showcase and Museum is two blocks away.

Spradlin said he figures almost everyone in town knows a former or current Rangerette. Young and old, the Rettes, as they call themselves, are all over Kilgore, reminders of the type of confident woman the town admires. Growing up, young girls in the area take dance, and as they reach their teenage years, many strive to make the Kilgore High School dance team, the Hi-Steppers. After high school, the most exceptional and devoted among them stand a good chance of earning a spot with the Rangerettes.

And though Motes didn’t seem to hold any particular grudge against the Rangerettes, she did have a grievance rooted in a high school drill team dispute. In Kilgore, dance is the air locals breathe, and that oxygen fed the flames of her anger—until everything went up in smoke.

“Makes a nice True Detective, right?” Spradlin said.

I did not realize Nancy Motes was a helicopter parent,” said Coleen Clower. The former instructor for the Hi-Steppers wore a neatly tied scarf and conducted herself with the poise of a former Rangerette, which she was. Sitting in her living room in 2019, she explained that she had known Nancy as the mother of Kyleigh Motes, a Kilgore High student who performed with the Hi-Steppers in her freshman, sophomore, and junior years. “Let me tell you what; I don’t think Kyleigh was even crazy about being on drill team,” Clower said. Not that the girl was burdensome. “She was very quiet—never had a problem with her at all. Just a sweet girl.” Folks around town said much the same thing about Kyleigh’s father, Kyle.

Kyle and Nancy Motes had lived in Kilgore for a decade by the time Kyleigh, their only child, became a high school senior. They kept mostly to themselves, and only a few neighbors and church friends knew them well. Nancy, now 62 years old, had the kind of life that many dream of. Kyleigh was well-behaved and a bright student. Kyle ran a successful construction company, while Nancy spent most of her time as a homemaker and mother, with plenty of hours to spare on her hobbies of repurposing secondhand furniture and volunteering with her church. The family’s finances seemed secure; according to a 2015 assessment, their home was worth more than $400,000.

Clower first took notice of Nancy’s behavior when Nancy served as a Hi-Stepper parent volunteer. Nancy had offered to transport watercoolers for an event and found herself struggling with the coolers’ retractable handles. “A couple of the handles were stuck, and she was trying to get them down so she could load them in her car,” Clower said. “I have never witnessed anyone so aggressive towards a cooler in all my life. She opened the back of her Excursion—huge vehicle—and was slinging them at the back of the car and seemed very put out by them.”

This outburst was odd, but it hardly foreshadowed the blowup that came in the spring of 2015, when Kyleigh failed to make the Hi-Steppers at the end of her junior year. Clower said that Kyleigh was cut spot because of an increasingly skilled and competitive talent pool that year. But Clower wasn’t directly involved with the roster decision. Emotions run high during tryouts, and she had developed a system to avoid favoritism and defuse complaints. Every year, she’d recruit three independent judges to rank prospective members on skills like splits and kicks. Before Clower even saw the scores, the principal would whisk away the results.

When Clower learned that Kyleigh had failed to make the final cut, she expected the girl to be devastated. Soon after the results were posted, she texted her: “Kyleigh, my heart is broken. I would like for you to consider serving as a manager and be a part of the team.”

Kyleigh didn’t respond, and Nancy never acknowledged the gesture. Instead, she and Kyle did something unexpected—and unprecedented. They contested Kyleigh’s scores and took their fight all the way to the Kilgore school board. In her formal complaint, Nancy wrote, “We believe there to be collusion with one or more of the judges and Mrs. Clower,” though she offered no evidence for the inflammatory claim. Nancy accused the judges of discriminating against Kyleigh and other tall girls in an effort to create height uniformity throughout the roster, and she said their decision had robbed her daughter of her senior year. “Every Friday night football game and performance, every time a Senior milestone happens,” she wrote, “it will be salt in the wound, a wound that will never begin healing for over a year, until she leaves Kilgore.”

Clower assumed the complaint would go nowhere. The district superintendent and the Kilgore High School principal both upheld the judges’ evaluations, but at a school board meeting that August, members heard Nancy’s case and voted to reinstate Kyleigh. Clower, feeling that her authority had been overridden and offended that the board’s vote seemed to validate the accusations against her, concluded she had no choice but to resign after the following school year. And in her last season running the Hi-Steppers, Clower decided that if Kyleigh was going to rejoin the team, then so should all the girls who didn’t make the cut. Every student who tried out that year was offered a spot.

Naturally, this resulted in a few awkward interactions. Nancy later complained that when Kyleigh rejoined the Hi-Steppers, “she was ostracized by teammates, many of whom she had grown up with and whom she considered best friends.” To spare her daughter further shame, Nancy—who had just spent months getting Kyleigh reinstated to the troupe—transferred her to Pine Tree High School, in nearby Longview. There, the girl spent a drill team–free senior year before heading off to college.

As the school year drew to a close, some locals still gossiped about Nancy Motes. There was talk that she had stalked one of Kyleigh’s ex-boyfriends and menaced him with her car. But months passed and the drama faded. Kyleigh began her freshman year at the University of Texas at Arlington, the Hi-Steppers hired a new director, and folks around Kilgore figured Nancy had moved on.

December 29, 2016, got off to a routine start for Nancy. She left her home and drove to Longview to shop for a pair of jeans at Cato Fashions. After stopping at Chick-fil-A to use the restroom, she got back on the road and spotted Patrick Shore, a recent ex of Kyleigh’s, driving out of a subdivision.

It was at this point that Nancy seemed to snap. As she would later explain, she suspected Shore was dating a local girl named Briana Duffield, and she devised a plan she believed would comfort her daughter: she would follow Shore until he met with Duffield, then take a picture of the couple to prove to Kyleigh that Shore had moved on quickly from their breakup and wasn’t boyfriend material. (Nancy’s logic might have been misguided—what teenager would be comforted by a photo of her ex in someone else’s arms?—but her intel was certainly off. According to Duffield, she and Shore never dated.)

To stay incognito, Nancy had brought along a disguise—a short, brown wig—though it remains unclear why she had it with her that day. She also had duct tape and a gun. She stuffed her mid-length dirty-blond hair into the wig, pulled a hat over it, and began trailing Shore.

For reasons that are unclear, Nancy eventually stopped tailing Shore and decided instead to search for Duffield. At some point, she pulled up the teenager’s Facebook page and saw that Duf-field was friends with Alexa Blair, and that they’d both been members of the drill team at Longview High School.

Nancy had a loose connection to Alexa’s mother, Dana, though their association is so confusing it practically begs for a diagram.

Nancy had a loose connection to Alexa’s mother, Dana, though their association is so confusing it practically begs for a diagram. According to the version of events presented years later in court, Shore had learned that Dana warned his mother about the rumors of Nancy’s disturbing behavior. Specifically, Dana told Teresa Shore that Nancy had once spread a tale about Kyleigh being pregnant, to prevent her then boyfriend from dumping her. Then, after the couple called it quits, Nancy drove to the ex-boyfriend’s house, and as he tried to back out of his driveway, she parked in his path and blocked him in.

Shore repeated the story to Kyleigh, and after their relationship ended, she passed it along to her mother. Nancy took the gossip personally and blamed Dana for Kyleigh’s split with Shore. But despite the tangled history between them, Nancy had never met Dana or Alexa.

Nancy knew that the Blairs lived a few blocks away from where she’d stopped following Shore, and because Alexa had been on drill team with Duffield, she thought Alexa would be able to tell her where the girl lived. She drove to a nursing home around the corner from the family’s house and parked in the facility’s lot. Still wearing the brown wig, Nancy turned off the engine and then grabbed the roll of tape and the gun. From her trunk, she retrieved an oversized snowman Christmas card.

Dana Blair was running around her house that afternoon, preparing to leave for the Cotton Bowl the next morning. “I was packing, ironing, and multitasking to get out of town,” Dana said. Alexa was watching Netflix in her bedroom.

Around six, Dana heard the doorbell. She thought it was her husband, Chris, who had just gone out to run some errands; she knew he didn’t have his house key with him, and she figured he must have forgotten something before heading out.

But when Dana opened the door, she saw a woman with short hair, wearing gloves and holding a large snowman card over the bottom half of her face. “Can I talk to Alexa?” the woman sweetly asked.

Ever since Alexa was young, Dana had taught her not to open the door for strangers. But at that moment, Dana’s guard was down. Not wanting to be rude to someone who seemed to know her family, she allowed the woman inside.

When Dana called Alexa to the door, she could tell from the expression on her daughter’s face that she didn’t recognize the woman. That’s when Nancy pulled out the gun.

“Give me your phones,” she said. In shock, Dana and Alexa handed them over. Nancy pulled the duct tape from her pocket and instructed Alexa to bind Dana’s wrists behind her back. After that, Nancy taped Alexa’s wrists together.

Alexa felt numb. Her parents had always been protective of her, and she recalled the exit strategy her dad made her memorize in case someone broke into the house: “Go out the back window and run to the nursing home.” But she couldn’t very well do that with a gun trained on her. “You feel like any wrong move you’re going to make might end up in something worse than what was already happening,” she told me later. “I was very still, almost like living in a dream.”

Dana, meanwhile, was panicking. “I was having an out-of-body experience,” she told me. “I could not get a grasp on reality, honestly. Alexa was just looking at me—she didn’t say a word, but I just know her, and she was looking at me like, ‘Get it together,’ because she knows I’m a freak-out person. I guess she thought she was going to have to be the calm one.”

As the Blairs watched, Nancy scrolled through Alexa’s phone contacts, scanning for Briana Duffield’s address. “You don’t know who I am, do you?” Nancy asked them. Dana admitted that they didn’t, and she apologized if she had somehow offended her. “You’ll know what this is about very soon,” Nancy said.

After she failed to find Duffield’s address, Nancy made an announcement. “I need you to take me somewhere,” she said. “We’re going somewhere in Alexa’s car.” Exactly what she had in mind was uncertain, but Dana knew she shouldn’t get in the car.

Alexa, who was barefoot, asked to retrieve her shoes from the bedroom. “Okay,” Nancy said, and Alexa walked down the hall to her room. As the girl stalled, trying to figure out if she could lock herself in the closet or escape through a window, Nancy told Dana to kneel by the door and went to check on Alexa.

In the split second that Nancy wasn’t watching, Dana slipped out of the tape, which Alexa had wrapped loosely, and dashed out the front door, running as fast as she could, bracing herself in case Nancy shot her in the back. “Home invasion!” she screamed over and over.

When Nancy and Alexa returned to the foyer, Dana was gone. And at this point, Nancy’s very bad plan took a turn for the worse.

It may seem hard to believe, but according to Nancy’s testimony, she initially didn’t consider her actions kidnapping. After Dana escaped, Nancy stood by the front door with Alexa, wondering if the woman was waiting for them in Alexa’s car. She marveled to herself over the Blairs’ compliance, even as she trained the gun on Alexa and told her that Dana shouldn’t have run. “That was stupid; why would she do that?” Dragging Alexa by the arm, Nancy directed the girl to her own car, which was still parked at the nursing home.

When she skidded out of the lot, Nancy realized they were being followed. Dana had run across the street just as her neighbors Lori and Travis Wilcox were pulling out of their driveway. Travis, who had been riding in the passenger seat, jumped out and ran back to the Blairs’ house with Dana, while Lori drove in the direction of two figures she’d seen walking toward the nursing home. Before she could reach them, she saw the pair get into a car and speed away. As Lori later testified, “I gassed it and took off” after them. During her pursuit, Lori had the sense to call 911 and read the suspected kidnapper’s license plate to the dispatcher. Then she continued tracking the vehicle through Longview neighborhoods, going as fast as 80 miles per hour—right up until Nancy ran a red light. “As soon as the light turned green, I tried to catch them, and they were gone,” Lori said.

Nancy was so absorbed by the chase that she momentarily forgot Alexa was in the car. In her testimony, she said a phone call jarred her back to her senses. It was her husband, Kyle, calling to ask about dinner. “I’ll be home soon,” she told him, as if she were picking up groceries. Then, she asked Alexa, “Will you call your house and see if the cops are there?” Nancy handed a phone to Alexa, who punched in the number for their landline. When Dana picked up, Alexa said, “Mom, she wants to know if you called the cops.”

Dana had called the police, and an officer had already arrived at the house, along with Chris Blair and a few concerned neighbors, but she told Alexa and Nancy that the cops weren’t there if they didn’t need to be. Dana felt the pressure building in her chest—disbelief, fear—and pictured herself at a candlelight vigil for her daughter. In her panicked attempt to put the phone on speaker so the others could hear, she accidentally hung up.

After the call, Nancy became increasingly paranoid. She started imagining that cars she saw on the highway were following her. Along the way, it may have dawned on her that she was committing a crime, and that she was in possession of evidence, because she threw Dana’s phone out the window and then smashed Alexa’s phone and tossed it too. After ditching the gloves and the wig, Nancy turned her attention to her captive.

Alexa kept her eyes fixed on the dashboard, holding the passenger-side door handle as she silently prayed and came to terms with the possibility that she might not live through the night. Meanwhile, Nancy interrogated Alexa:

Do you think you’re perfect because you’re a Rangerette?

How are you so calm—is that because of your Rangerette training?

Do you have a boyfriend? Who is your best friend? Is Briana Duffield your friend?

When Nancy came over a hill on the southeastern outskirts of Kilgore,

beyond the fields and the six-pump gas station and the country store, she pulled into a storage facility where she and Kyle rented space and parked near unit 14. “Where did the gun go?” Alexa heard her say while Nancy frantically rummaged through the car. (She didn’t find it, and investigators were never able to recover the weapon, although Nancy later admitted to using a gun when she pleaded guilty to the kidnapping.) Undeterred, she opened the door to the space and pushed Alexa inside.

“You haven’t done anything wrong,” Alexa remembers Nancy saying, as she wrapped duct tape around Alexa’s lower legs. “But you’ve seen my face, and I’m not going to jail.” She ordered the girl to lie down, and Alexa squeezed her eyes shut and did as she was told.

All of Nancy’s frustrations from the previous few years seemed to lead to this surreal, horrifying moment. She knelt on Alexa’s chest and choked her. Alexa heard something crack in her neck. “This is for my daughter, Kyleigh Motes,” Nancy said. After that, Alexa passed out.

Alexa doesn’t know how long she was unconscious, but when she came to, she played dead, to no avail. Nancy saw Alexa’s chest moving and seemed surprised. “Oh, are you still breathing?” she asked.

Nancy saw Alexa’s chest moving and seemed surprised. “Oh, are you still breathing?” she asked. But rather than finish the job, Nancy changed course.

But rather than finish the job, Nancy changed course. It was as if coming right up to the edge of murdering someone had convinced her to go no further. She decided to head home, where the salmon dinner her husband had cooked was getting cold. On her way out, she smoothed a piece of tape over Alexa’s lips. Then she left the unit and shut the door.

When Alexa heard Nancy’s car pull away, her Rangerette workouts paid off in a way she never could have anticipated. Minutes after she’d been strangled to the point of unconsciousness, Alexa exploded with energy, ripping the heavy tape from her legs. And while Nancy was driving home to her fish dinner, Alexa was bolting out of the storage facility.

Scanning the unfamiliar parking lot and surrounding streets, Alexa spotted an eight-foot wooden fence—the first one she saw that wasn’t topped with barbed wire. She sprinted to it, scaled the fence, and then climbed a second one. On the other side, she found herself in a residential neighborhood. Looking through the window of a house, she glimpsed a mother and her baby and decided to knock on the door and ask for help. “At first, my husband and I didn’t know whether to believe her,” the woman, Taylor Welch, told me. “But as I saw her face, I recognized her as Dana Blair’s daughter. She was wearing a white shirt that had the word ‘Rette’ on it, so I realized who she was, and that she wouldn’t be lying about being kidnapped.”

Alexa used Welch’s phone to call 911, and a medic transported her to the police station, where she briefly hugged her parents before providing a statement to an investigator. Meanwhile, officers arrived on the Motes’s doorstep. When a detective asked Nancy about her whereabouts that afternoon, she was indignant. She didn’t know Dana or Alexa Blair, she said. Certainly, she didn’t know anything about a kidnapping. She had no idea why anyone would call 911 and report her license plate. Even when the police took her into custody on suspicion of kidnapping, she maintained her innocence. Crossing her arms over her chest, she swore, “I have never worn a wig.” She grew sarcastic and angry, almost snarling at detectives as they asked what grudge she had against the Blairs. “Why would I kidnap someone I don’t even know?” she asked. “It makes no sense. It makes absolutely no sense. I don’t know why they would say that.”

The next morning, as Nancy was making bail, the Blairs were throwing their bags into the back of their car and driving to Arlington, where Alexa would perform in the Cotton Bowl.

“You do not have to do this,” Dana told her. “You don’t have anything to prove.”

“I am performing,” Alexa said. “I made the line. I made tryouts. I am kicking. I am dancing at my freshman Cotton Bowl. I’m doing it.”

Alexa didn’t talk much about the incident in the months that followed, and few friends or acquaintances asked for details. Instead, they gathered what they could from local newspaper articles with headlines like “Warrant: Suspect Choked Kidnapped Rangerette” and “Investigation Continues Into Armed Abduction of Freshman Rangerette.” When she saw the first detailed account of the crime in the Kilgore News Herald, she realized everyone in town was probably reading about the worst moment in her life too. “I wasn’t mad that it was out,” she said, “It was just hard to reread and relive.”

Once the initial uproar subsided, though, the Blairs’ ordeal fell off the radar. Nancy maintained her innocence for the next two years and went about her normal life, right up until her criminal trial was set to begin in April 2019. Faced with overwhelming evidence, she pleaded guilty to two counts of aggravated kidnapping and was sentenced to five years in state prison. The crime, which had kicked the small-town gossip mill into overdrive, wound up producing little drama in the courtroom.

Studying Nancy’s face at the April 29, 2019, sentencing hearing, Alexa took her in for the first time: the shoulder-length hair parted at the side, the mascara running into the creases beneath her eyes, the mouth set in a deep grimace. Alexa couldn’t take her eyes off her. She had spent a pivotal moment of her life with this woman, yet she had barely seen her; Alexa had kept her head down throughout the kidnapping. Now that the threat of violence was gone, Alexa could gaze safely upon Nancy, and the longer she looked, the angrier she felt. “For her to continue for so long not telling the truth,” Alexa said, “I think that was the most aggravating part.”

After the criminal proceedings wrapped up, the Blairs sued Nancy, asking for $700,000 in damages. The civil trial began last June, providing Dana and Alexa with an opportunity to have their story heard by a judge. Many Kilgore residents also hoped the proceeding would offer clues as to what drove Nancy to commit such a shocking crime.

Nancy didn’t attend the trial in person, but video of her pretrial deposition was played in court. Attendees watched as Nancy explained that she hadn’t been angry or upset with Dana or Alexa Blair in the hours before she kidnapped them. Rather, Nancy said, the Blairs were simply unlucky bystanders who became the targets of a more general frustration that boiled over that December afternoon, an ire that had begun simmering when Kyleigh lost her spot on the Hi-Steppers. “When I look back at it now, it looks totally crazy,” she said. “Why would I be mean to them? I didn’t even know Alexa.” In a separate statement, which was introduced as evidence during the trial, Nancy wrote, “The event was a strong response to people bullying my daughter. It started when my daughter was cut from the Kilgore drill team in 2015, after having been a member for three preceding years, and the judges were all previous Rangerettes.”

In Nancy’s deposition, John Sloan, the Blairs’ lawyer, asked, “Do you think the way you feel even approaches the way Dana Blair feels?”

“I experienced it for close to two years,” Nancy said, “the way my daughter was treated.”

Now that the threat of violence was gone, Alexa could gaze safely upon Nancy, and the longer she looked, the angrier she felt.

“So your pain for your daughter not making drill team and something you imagine Mrs. Blair saying to Mrs. Shore approaches what Dana and Alexa Blair experienced?”

“I said I can imagine the pain she felt,” Nancy replied. “I don’t know what she has felt.”

Nancy also denied critical aspects of the crime she’d already pleaded guilty to in her criminal case. When the Blairs’ lawyer showed a photo of the burst blood vessels in Alexa’s eyes and the bruises around her neck, Nancy said she couldn’t imagine how those marks got there. Aware that investigators never recovered a handgun, she also denied having a weapon during the kidnapping. (The Moteses owned several firearms, but because Nancy hadn’t fired a weapon, there was no ballistic evidence to link any of those guns to the crime.)

“Did you have a gun?” Sloan asked.

“Not that I recall,” Nancy said.

“You don’t recall having gun?”

“I pled guilty to having a gun.”

“It just blows my mind to hear her say it over and over again,” Alexa said of Nancy’s claim that she didn’t use a gun in the kidnapping. “I want to see if she can say that to my face.” (Nancy, Kyle, and Kyleigh Motes all declined interview requests for this story.)

The defense tried to use the Blairs’ resilience against them, arguing that the family didn’t suffer significant damages from the kidnapping. After all, the family drove to the Cotton Bowl the next morning. “This thing could have gone a whole lot worse than it did,” Nancy’s lawyer, Joe Young, told the judge. The defense attempted to paint the picture of a happy ending: how Alexa went on to finish Rangerettes the following year and then transferred to Texas A&M University, where she graduated in 2020; how she got a job working as the director of a middle school drill team in Central Texas. Meanwhile, her parents moved to a new home and Dana continued leading the Rangerettes. Everyone was flourishing, the defense argued. No harm, no foul.

“I think that if she intended her harm, she had plenty she could have done and she didn’t; Alexa is fine,” Kyle Motes testified, before quickly walking it back. “I mean, she’s not fine. I didn’t mean to say it like that. It’s as—if [Nancy] went up there for harm, there was ample time and opportunity for harm before they got to the storage [unit].”

Alexa told the court that she tries to avoid thinking about that night. “I don’t like talking about it,” she said. “I keep myself busy because that’s the only way I can survive without being upset or scared. So that’s what I’ve been doing for a long time. It sucks.”

Dana tortured herself with guilt over her decision to let Nancy into their home. “I’m an overprotective parent,” she testified. “Anyone who knows me knows that. That day, I opened my door, and someone came in and took away my ability to protect her.”

Young asked if she had forgiven Nancy. “I was doing a pretty good job of it until I heard she denied having a gun and denies choking my daughter,” she said.

At the end of the two-day trial, the judge ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and awarded them $575,000 in damages. On the way out of the courtroom, Dana and Alexa stood by the doorway and told me that the judge’s decision validated their experience. “Listening to our story and taking it all in, the facts,” Alexa said. “Hearing it said out loud.” They also said they felt unsettled by Nancy’s looming release. (Nancy was granted parole last November, after serving two and a half years. According to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, she was released to an address in the Longview-Marshall area, where she is required to reside until the end of her sentence in April 2024, unless the state approves a plan for her to move.) “She’ll be getting out of jail, so it’s not like—it’s not over, and she’s going to be out in the world,” Alexa said. “I don’t know if it’s over or not.”

As word of the judgment made its way around Kilgore, more than a few locals commented that they were practicing their aim, for self-defense, should they find themselves on Nancy Motes’s hit list. (In her testimony, Nancy rattled off the names of individuals she believed had disparaged her on social media, as if she might still be holding a grudge.)

Down at the Kilgore Police Department, Mayor Spradlin was sitting on a flatbed trailer in the parking lot, helping load water bottles for a police appreciation parade when he heard news of the outcome. He couldn’t say if many Kilgore residents were actually worried about Nancy’s release. “I heard she moved,” he explained. In the four years since the kidnapping, Kyleigh had graduated college and was living in another part of Texas. Kyle had relocated out of state. Spradlin’s heart went out to the Blairs, but he also felt for Kyleigh and Kyle. “They didn’t wish this on anybody.”

While volunteers arrived with more supplies, Spradlin shrugged as if there were nothing more to say, except that some parents just can’t seem to get out of their kids’ way. He mentioned a teacher who’d recently observed that mothers and fathers are becoming more meddlesome than ever. They aren’t just helicopter parents—this is a new breed to watch out for. “These are lawn-mower parents,” he said. “If you get in their way, they’ll mow you down.”

This article originally appeared in the February 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Beauty Knows No Pain.” Subscribe today.

video: Inside the story

Writer Katy Vine reflects on the reporting of this story.