The toe on Candy’s left foot was bleeding profusely. Candy stared at it and fished in her purse for the keys to the station wagon.

Now you’re in the car. You’re normal. The car is still here. Everything looks the same.

Her mind went blank, and in the few lost moments, she was vaguely aware the car was moving.

One step at a time, just do one thing at a time, and it will be all right. Don’t think about the house.

She stared down the main street of Wylie and imagined that her car was not moving at all. Then the main street was gone. She stared at a stop sign. It scared her; she needed movement.

You can’t lose control now. Nothing is changed.

She glanced down at her lap and felt a sudden chill in her legs. Her blue jeans were soaked with water. The antiseptic smell of fabric softener flooded her nostrils, and for a moment she thought she would be sick.

Why am I wet? That smell. Can’t panic. Normal. Left, right. Why won’t the car go faster?

Candy’s toe began to throb.

Oh God, it hurts. Cut my toe on the storm door, that’s what happened. How can I be wet? Oh God, it hurts. No one will know. You couldn’t have done it. No one will know.

The white station wagon wound through the Collin County backcountry. After a while it pulled back onto FM Road 1378 and continued north past an old church and a red schoolhouse, across a narrow stone bridge, and up a hill. At the crest it turned right onto a pitted gravel road that disappeared into a forest of oaks and hackberries.

At last the landscape was familiar again. Down a slight incline, left onto the gravel, and up the steeply inclined driveway. Only now could the house be seen, sitting on a little knoll, shrouded by two or three red oaks. It was like a contemporary cathedral in wood and glass, with the stylishly unfinished look of a Colorado ski lodge. Around the expansive yard was a corral of white horse fence. The station wagon nosed into the double garage and stopped.

Nothing is changed. Out of these clothes. Calm. Dry and clean. Normal.

She ran upstairs, stripping off her blouse and blue jeans as she entered the bedroom. She wiped the blood from her third toe and wrapped a Band-Aid tightly around it, flinching as she felt how deep the cut was.

I did it on the storm door. We never have fixed the storm door.

She took her shirt into the kitchen and placed it in the sink. She poured the detergent and turned on the water.

Oh, no, the smell again.

She started to retch but quickly regained her composure.

She left the blouse soaking in the sink and went upstairs to find a pair of blue jeans the same shade as the ones she had just taken off. She took a quick shower and washed her hair. As she did, she noticed an open cut at the hairline on the right side of her forehead. She dried her hair with a towel and then went to get another Band-Aid. But the springy hair around the wound kept the bandage from sticking. Finally she gave up, wrung out her blouse, put on the new blue jeans, threw the old ones in the washer, and waited while the dryer dried her blouse.

Thank goodness it was a burgundy colored shirt.

The last thing she did was replace her rubber sandals with a pair of blue tennis shoes. She laced them up tightly to keep pressure on the toe bandage. She was ready to pick up her children and Betty Gore’s daughter Alisa at church.

The children’s puppet show in the sanctuary was coming to a close when Candy pulled into the parking lot. She caught up with a friend who was going in to join the other women for lunch. “Oh Barbara,” Candy said breathlessly. “I went down to Betty’s and we just got to talking, and then I looked at my watch and thought I had time to go to Target and get Father’s Day cards and I drove all the way to Plano. But then when I got there I realized my watch had stopped and I was late, so I didn’t even go in. We’re taking Alisa with us tonight to see The Empire Strikes Back. That reminds me, I’d better go check on the kids.” As Candy headed for a classroom, it crossed her mind that she might be limping. She made a special effort to walk straight. In an empty room she found a mirror and dabbed at the cut near her hairline. Even after the blood had been stanched, she could feel it running down her forehead, exposing her.

No one must know. Day like any other.

When Candy left, one of the women noticed something odd. Candy Montgomery, who always wore rubber sandals in the summer, was wearing a pair of blue tennis shoes.

The afternoon passed in a fog. Candy bundled the three children into the station wagon. They were an odd comfort; they kept her occupied, kept the dragons at bay. At home, after she told Alisa to get ready for her swimming lesson, Candy phoned her husband at work.

“Pat, we just got home from Bible school and wanted to be sure you get enough money at the bank, because Alisa is going to the movie with us. The kids nagged about it after you left this morning, and so I promised them I’d ask Betty if Alisa could stay another night. But then I had to go to Betty’s to pick up Alisa’s swimsuit and we got to talking and I lost track of time, and then when I went to Target I noticed my watch had stopped and I missed the whole Bible school program.”

“Uh-huh,” said Pat. He had just returned from a Texas Instruments office picnic and was anxious to make some computer runs.

“Betty said Alisa could spend the night.”

“Listen, honey, that’s fine with me. I’m about to go to the bank now.”

“Pat, would you happen to know where Allan is working today?”

“Allan Gore? No. Why?”

“It’s not important. We’ll meet you in the parking lot about fifteen of five.”

Pat hung up and thought, “What was that all about?”

At 410 Dogwood Street, the home of Allan and Betty Gore, their two children, and their two cocker spaniels, no one came or went on the afternoon of June 13, 1980. The phone rang intermittently but wasn’t answered. Around noon a delivery man for a parcel service rang the doorbell but got no response. Around four Allan Gore called from the Dallas-Fort Worth Airport, where he was about to board a plane. After ten or eleven rings, he hung up. The only sign that the house was occupied at all was the muffled sound from within of a baby crying at the top of her lungs.

Behind the house the two dogs skittered nervously around the yard, howling and whimpering by turns, as if they were confused or perhaps frightened.

Candy’s son talked excitedly of Star Wars, but his mother scarcely listened. She and the children sat in the expansive parking lot at Texas Instruments, with the windows of the station wagon rolled down to alleviate the stifling heat, and waited for Pat’s conference to break up so they could go to the movies. It was a little after four-thirty. The name came out of nowhere: “Bethany.”

Candy didn’t know what the children were discussing—probably something about brothers and sisters—but she heard Alisa say her baby sister’s name, and suddenly Candy’s body tensed all over. The sense of dread rushed back. With it came the strong aroma of something soft and clean and antiseptic; it tickled the nose and infused the sinuses. There was no escaping it.

A Room Full of Blood

Allan Gore had left for St. Paul late that afternoon. It was an awkward time and an awkward trip. Back in September, when he left Rockwell International to join an obscure but promising electronics company in Richardson, he had known he would have to work long hours, but he tried to avoid working on weekends. This time Allan and two of his colleagues had to be in Minnesota over the weekend to make certain one of their largest clients, the 3M Corporation, had a fully functional message-switching system by next week. Actually, it was the kind of trouble-shooting that Allan would have loved, under other circumstances. He liked to travel, he liked the challenge, and he especially enjoyed the camaraderie of the half dozen men trying to hang in there against the colossal firms like Rockwell and Texas Instruments and E-Systems and Northern Telecom and all the other illustrious names that proliferated up and down North Central Expressway in the so-called Silicon Prairie.

But Allan wasn’t enjoying this particular trip, and for a familiar reason. Betty couldn’t stand to be left alone, even for one night. This trip would be easier on her because of the vacation they were planning. A week from now they would be in Europe, without the children for the first time in four years, and last night she had been positively radiant, describing the upcoming trip as a second honeymoon. Then this morning she had broken down again, but she and Allan had a good talk and parted happily. Allan promised to call her from the airport; the sound of his voice would reassure her.

On the way to his gate, he stopped at a pay phone and dialed home. The phone rang seven or right times, so he hung up and dialed again. When he got no answer, he assumed that Betty was taking her afternoon walk with Bethany. Just then he saw one of his colleagues and joined him in the boarding area. They could discuss the new software on the way to St. Paul. The flight was uneventful and on time. Well before eight the men had checked into the Ramada Inn on Old Hudson Road, their accustomed home when working on the 3M account. They agreed to meet for dinner around nine.

Allan sat on the bed in his room, going back over the day, wondering if he had forgotten something Betty had said that morning. He called his house again, let the phone ring fifteen times, then got an operator to dial the number. Still no answer. Betty could be moody, but she would never leave the house in the evening without telling anyone.

Allan called Richard Parker, his next door neighbor and the real estate agent who sold them their house. When Richard answered, Allan could hear small children in the background. “Richard, this is Allan Gore. Sorry to bother you, but I’m out of town and I’ve been trying to get Betty on the phone. I think the phone must be out of order. Would you mind knocking on the door over there just to see if she’s home?”

“Yeah, okay, partner,” said Richard, a little peeved at the imposition. “I guess I can run over.” Wearing only slacks and an undershirt, he slipped out the front door and hurried across the Gore lawn in his bare feet. He had always thought Gore was a weird guy, quiet and unsociable. He had sold the Gores that house three years ago, and he didn’t know them much better now than he had then. Allan was one of those guys who always kept his yard so neat. Quiet guys usually had neat yards.

Richard rapped hard on the door at 410 Dogwood and waited for an answer. He rang the doorbell. He waited a few more seconds and then sprinted back across the grass. “No answer, Allan. She must be out.”

“Okay,” Allan said. “Thanks for checking. I’ll call her later.” Now Allan was starting to worry. On an impulse he dialed the Montgomerys’ number. Candy answered after one ring. “Candy, this is Allan. Have you seen Betty?”

“Oh, Allan, where are you?”

“I’m in Minnesota on a business trip. I’ve been trying to get Betty, but no one answers, and I thought you might have talked to her today.”

“I saw her this morning when I went to pick up Alisa’s swimsuit.”

“Did Betty seem all right?”

“She was fine,” said Candy. “She did act like she was in a hurry for me to leave.”

“Do you know where she might be?”

“Maybe she went to a friend’s.”

“No, she wouldn’t go out this late. It scares her.”

“Well, I’m sure there’s nothing wrong.”

Candy’s voice was full of concern. “When I went over to pick up Alisa’s bathing suit she was okay. I remember she was sewing, and we just talked for a while, and she gave me some peppermints for Alisa and told me how she wouldn’t put her head under the water unless she got a peppermint afterward. And I took the peppermints and left.”

“Is Alisa there now?”

Candy called Alisa to the phone. Allan inquired about the swimming lesson and asked whether her mother had mentioned going out that evening. Alisa didn’t remember anything, so Allan told her to have a good time and be polite to the Montgomerys. Then Candy came back on the line. “Allan, is there anything I can do? I’d be happy to go over to the house and check on them for you.”

“No, that’s all right, I’ll call the neighbors.” A few minutes later Allan went downstairs to the motel restaurant. He returned to his room around ten o’clock, well past Betty’s bedtime. Still no answer at home. Allan called Richard again and asked him to see if Betty’s car was in the garage.

Richard went as far as the chain link fence between the two houses and peered into the garage. Then he went back to the phone and said, “Yeah, Allan, there’s only one car there, and the garage is open and the lights are on.”

“That’s strange,” said Allan. He considered the possibilities. It had to be some emergency; perhaps the baby was sick. He called the Plano hospital and the Wylie police. They had never heard of Betty Gore. Allan felt helpless. He needed to talk to someone with a calm, level head and a sympathetic ear. He called Candy Montgomery.

“One car is gone, the garage door is open, and the lights are on,” Allan said. “She never leaves that garage door open. Has she called there or anything?”

“Oh, Allan, no she hasn’t. Let me go down there and check the house. Or let me check the hospitals for you.”

“No, no, I just wanted to make sure you couldn’t remember anything else. I’ll get the neighbors to check again.”

“Don’t worry about Alisa, Allan. We have her and she’s fine.”

Allan hung up and felt sick. Why didn’t Betty call him? Why didn’t anyone know anything? Why couldn’t he make the one phone call that would make everything all right? For the third time he dialed Richard Parker’s house, but this time he didn’t waste words. “Richard, I’m really worried about her. Please go back over there and check all the doors and the garage again. If she had to leave in a hurry, maybe she left a note somewhere.”

Richard sighed—he didn’t like the responsibility and was a little frightened by Allan’s panic—but he went all the way around the back fence, into the alley, and up the Gore driveway. He was startled to see two cars in the garage. The Volkswagen Rabbit was pulled up so far that he hadn’t been able to see it from the fence. Richard walked into the garage and tried to open the door to the utility room. He could see a light under the door, but it was locked. Something about the house—the burning lights, the open garage, the silence—disturbed him. He left the way he had come.

“Something’s wrong, Allan. I don’t know what, but something’s wrong. Both cars are there and the lights are on, but nobody answers.”

“Richard,” said Allan, “I want you to go and get in that house any way you can.”

Richard didn’t say anything for a moment. “Okay, Allan, I guess so.”

“Call me back when you find out something. Here, write down my number.”

Richard took down the number and hung up and took a deep breath. Then he found his realtor’s keys, hoping he had one that fit the Gore house. Meanwhile, Allan was growing skeptical of Richard’s resolve; he had sounded so tentative. So Allan called Jerry McMahan, a computer analyst at Texas Instruments who lived across the alley from the Gores.

“Jerry, something is wrong over at my house. I’ve been trying to get Betty but nobody answers. The lights are on and the doors are locked. Would you get a flashlight and go over there and see what you can find out?”

“Okay, I’ll be back in a minute.” Jerry stepped into a jumpsuit and his house shoes and padded down his back driveway with a flashlight. In Allan’s garage he knocked loudly on the utility room door but got no answer. Then he walked into the back yard and tried to force open a sliding glass door, but it wouldn’t budge. He continued around to the front of the house, peering in windows as he went, and rang the doorbell, but still there was no sign of life. Back at his own house he told Allan, “The lights are on in there, but I can’t see anything wrong.”

“Jerry, there is something very definitely wrong.”

“She’s probably just out with friends.”

“No, she’s not with friends. I’ve already tried that. Get in that house and see what’s wrong. Take the windows off, force the doors, whatever it takes.”

As soon as Jerry told his wife what was happening, she grew frightened and insisted that he not go over there alone. So Jerry called Lester Gayler, a barber who lived next door to the Gores on the other side from Richard Parker. Two minutes later, the two friends met in the alley behind the Gore house. When Richard walked out into the yard carrying a big silver ring full of house keys, he was startled to see Jerry and Lester.

“What the hell’s going on?” Jerry asked.

“I don’t know,” said Richard. “Gore just called and said to get in the house. I’ve got these realtor’s keys. Let’s try them on the doors.” The three men walked up the Gore driveway. While Richard tried his keys, one by one, on the utility door, Jerry and Lester tried to force open the sliding door again. It was the fifth time the house had been checked that night, but doing it as a group invested the procedure with a seriousness that made them all uncomfortable. If there was something wrong inside, they weren’t sure they wanted to see it.

None of Richard’s keys worked, so someone suggested they try the front windows. Together they walked around to the street side of the house, and Jerry and Lester inspected a large window into the dining room to see if it could be pried open. Meanwhile, Richard went to the front door to try his realtor’s keys again. As he placed the first key in the lock, a chill ran down his spine. The door swung open. He had not even turned the key. “This door,” he said, turning to Jerry and Lester and stepping away from it, “this door is not locked.”

The two men joined Richard on the porch, but for a moment no one made a move to go in. Richard stuck his head in the crack the open door had made: “Betty?” he said. Then louder: “Betty!” Finally Lester pushed open the door, and the three men entered the foyer, illuminated by the lights burning in the den to the right and in the bathroom to the left. All the hall doors were closed. Lester stopped at the first one, opened it, and flipped on the light inside: Richard looked over Lester’s shoulder: a child’s bedroom. Nothing unusual. They continued down the hall to the next room. Meanwhile, Jerry peered into the bathroom, and on the tile he saw a dark, caked substance. “Oh, no,” he said, “something bad is wrong.”

At the second bedroom, Lester opened the door and flipped on the light. As soon as he did, Richard heard the hacking wail of an abandoned child and the simultaneous exclamation of Lester: “Oh, my God, the baby.”

From the doorway Richard could see Bethany in her crib, half sitting, half lying, her legs folded under her, her face blotchy and red, her hair tangled and dirty. Her skin was stained with her own excrement. Her poignantly hoarse crying curdled their blood. She had obviously been there a long time. Richard quickly gathered up the baby. Cradling her head against his shoulder, he hurried back to his house to call the police.

As Richard left, Jerry and Lester went on to the master bedroom, where they found nothing. That left the other half of the house. They entered the living area, and Jerry went into the dining room on the right while Lester took the kitchen on the left. They walked slowly, turning on lights as they went. Both of them were increasingly aware of a pungent odor that seemed to follow them through the house.

Finally Lester made his way through the kitchen to the utility room door. “Oh, my God, don’t go any farther!” Lester shut the door quickly, and in the stunned silence of the moment it was difficult to tell whether he was talking to Jerry, to himself, or to someone on the other side of the door.

“She’s dead.”

Lester had not seen the body. He hadn’t seen anything but blood—thick, congealed reddish-brown oceans of blood glistening on the tile of the utility room floor—and he didn’t want to look any further than that.

From the dining room, some fifteen feet away, Jerry saw the look on Lester’s face and heard the shock in his voice and walked tentatively toward the utility room. As Lester moved away, Jerry cracked the door open and, without getting any closer, looked in. He saw only a glimpse, but it was enough. He shut the door. “She’s blown her head off,” he said. Lester went to the telephone on the kitchen counter, thinking we would call the police, but just as he reached for the receiver, the phone rang. For an instant, Jerry and Lester froze.

Lester picked it up. “Hello.”

“This is Allan.” He had called because he couldn’t wait any longer.

Lester hesitated. Jerry sensed what was happening. “Is that Allan?” he asked. Lester meekly handed him the phone.

“What did you find?” Allan’s voice was tense and shaky.

“I’m afraid it’s not good,” said Jerry, finding no words to describe what he had just seen. “But don’t worry—the little one is okay.”

“The baby is okay?”

“Yes.”

“What about Betty?”

“I’m sorry, Allan.”

“What happened?”

Jerry had to say something. “I don’t know for sure.”

“What do you think?”

“It looks like she’s been shot.”

“How? We don’t have a gun.”

“I’m sorry, Allan. I wish I had another way to say it.” After a silence, Jerry said, “What about Alisa, Allan? Do you know where she is?”

“Yeah, she’s fine. She’s fine.”

“I wish there was something else I could say, Allan. We’ll stay here and explain everything to the police.”

“Okay, thanks, Jerry.” Allan was stunned and so disoriented that he temporarily forgot where he was. Not knowing what else to do, he called Candy Montgomery again.

Pat was a little peeved when the call came around eleven-thirty: he and Candy had just started making love. “What timing,” he said, as Candy reached immediately for the phone.

“Candy.” Allan’s voice was distant and flat. “I have some bad news. Betty is dead.”

“Oh, Allan.” Candy’s voice broke. “What happened?

“It looks like she’s been shot. The neighbors found her.”

“What about Bethany?”

Allan didn’t even hear the question. “I know that there have been some things bothering her lately,” he said, “and I know she’s been upset, and she was two weeks late with her period. But I never thought that she would—”

Allan stopped, and Pat noticed tears forming in Candy’s eyes. “What can I say, Allan?” Candy was almost whimpering.

“Please keep Alisa for a while and don’t tell her what happened. I want to tell her.”

“Oh, Allan, are you going to be all right?”

“Yes, I’m okay. I’ve got to go.”

Candy hung up and began to sob. Pat put his arm around her shoulders. “Is she dead?” he asked.

“I don’t know, I didn’t ask. How can you ask something like that? But she must have been, because the neighbors found her.”

A gun, she thought. A suicide. It’s all right now because it happened with a gun.

Allan Gore wondered whom he should call next. He stared at the wall, and his mind went blank for a moment. Then he saw Betty, as he had seen her for the last time that morning, as he would see her for months to come. She had walked out onto the driveway with Bethany in her arms. As Allan pulled away, she raised Bethany’s little hand and waved it at him, and for the first time that day Betty had smiled, really smiled.

Candy Montgomery slept for three hours and then got up, alone, to fix breakfast. Pat and the children and Alisa Gore were still sleeping. The kids didn’t know yet, of course. She and Pat had stayed up talking about Betty for a while, but when Pat was unable to get any information from the police, they gave up and lay staring at the ceiling. They tried to sleep. Pat fell asleep first, but Candy kept thinking about the last phone call from Allan. After telling them that Betty had been shot, he had called back to give them his flight schedule. Before hanging up, he said something else. “I’ve talked to the police, and I mentioned that you were over there, so they’ll probably be calling.” It was the first time Candy had thought about it.

Candy went through the rituals of a housewife, making the bed, putting away a few toys. She called softly to the children to get up, and they limped down the stairs for breakfast. Pat went outside to mow. The kids finished eating and ran out to play.

Then the phone calls started. “Candy, have you heard?”

“About Betty? Just that she was shot.”

“Well, don’t turn on a radio where Alisa can hear. I haven’t heard it, but I understand it’s all over the news.”

“Oh, is it?” Candy felt a twinge; she stared straight ahead. “Thank you for letting us know.”

The phone rang again almost as soon as Candy hung up. Since it was Saturday morning, everyone was home, listening to the radios and trading information by phone.

“Candy? Do you know Betty’s dead?”

“We heard last night. It’s so awful.”

“The police just left. They say she was murdered—with an ax.”

The dread descended again. “An ax?”

“It must have been some very sick person.”

The telephone wouldn’t stop ringing. Candy went out into the yard and looked for something to do. She got the hedge trimmers and clipped the shrubbery around the white fence. It was hard, messy work, but she pitched into it whole-heartedly, rubbing blisters on her hand from pressing the clippers so hard. Then she fielded more calls, many of them from shocked church members who naturally called the woman who always seemed to know what was going on: “Who could have such a diseased mind, to use a weapon like that?” “If they ever catch the person who did this, there’s nothing they could do to him that would be punishment enough.” “I just hate it that Betty suffered.” “They say they have a bloody footprint.” The bloody footprint was fast becoming the sole detail of the crime known to every person in Collin County.

Around lunchtime the calls began to dwindle. A friend reported that Allan was home and that when he was told that Betty had been killed with an ax, he almost collapsed. Candy sat by the kitchen table, phone cradled between her ear and shoulder, a pair of garden shears in her hands. As she spoke, she worked the garden shears back and forth, pressing with all her might as the blades cut through a pair of rubber sandals. She continued her work for several minutes, long enough to destroy all semblance of pattern on the soles, rendering the shoes into a messy heap of rubber. After hanging up the phone, she gathered the scraps and carried them to an outside garbage can.

What the Hypnotist Learned

Candy, by her own report the last person to see Betty alive, became the main suspect in the case in a matter of weeks. The police questioned her several times, but her version of the day’s events and of her relations with the Gores was always airtight. Or so it seemed, until Allan Gore admitted that he had ended an affair with Candy seven months earlier. That gave the police a motive for killing, what they had been unable to fathom when they questioned the bright, attractive housewife. They arrested Candy Montgomery and charged her with murder. For a while, Candy denied the charges.

After she was released on bail, Candy stopped reading the newspapers and watching the TV newscasts. But Pat was heartened by the way everyone stood by them, no matter what new evidence was leaked to the press. The church had been overwhelmingly supportive. Scarcely a day went by that they didn’t receive at least half a dozen greeting cards and “Have a nice day” cards and “Thinking of you” cards, some of them awkwardly worded, all of them well intentioned. People who hadn’t written or seen the Montgomerys in years were visiting Hallmark stores all over America, trying to find messages suitable for a family awaiting a murder indictment. Candy wrote replies to them all.

Candy had hired a lawyer she knew from church, Don Crowder, to represent her. Crowder, a partner in a small firm with attorney general Jim Mattox, usually handled personal injury work. He had never been close to a murder case before, and suddenly he had the hottest one in Texas on his hands. As he began to delve into the case, he realized he was going to need help prying the memories of that horrible June day out of Candy. He enlisted the aid of a Houston psychiatrist, Dr. Fred Fason, who was a good-humored, fatherly charmer with a huge nose, bushy eyebrows, and a sweet, intelligent mouth. He called himself a River Oaks shrink; he dealt with a lot of Valium-addled socialites and impotent millionaires. Dr. Fason didn’t mind if people knew that, either; it was the only advertising he had.

That’s why when Crowder called in early August, Fason was quick to say that he didn’t care much for the courtroom work—it was bad PR. But when the attorney outlined the case, Fason was sufficiently intrigued to say that perhaps he would serve as a consultant and see the client once for diagnosis.

Candy and Crowder flew to Houston, where Fason administered a battery of tests. Afterward, the psychiatrist pronounced himself hooked on the case. He agreed to try to break into Candy’s memory through hypnosis. Two weeks later Candy returned to Houston accompanied by one of the Crowder associates, Elaine Carpenter. Carpenter noticed that Candy seemed more detached than usual, almost numb, on the plane ride down, and as they waited in Fason’s dark, antiseptic reception area, Candy grew even more vacant.

When Fason arrived, he offered a cheery greeting and then ushered Candy into his spacious office. Candy felt comfortable around Dr. Fason; she found him businesslike yet playful at the same time. After Candy disappeared, Carpenter settled back in a chair and perused a few old magazines. Hours passed, with no one coming or going. Carpenter started pacing about, bored and wondering what could be going on inside. Suddenly she heard a shriek. It was loud and eerie, and it came from Fason’s office. Then she heard several more in quick succession; they were low-pitched, like moans, or like the noises people make when they’re having nightmares. She couldn’t tell whether they came from Candy or someone else. And they didn’t stop.

It was Fason’s voice that got to Candy—soft, deep, resonant, the source of his power and his art. Fason was a psychiatrist, but he was also a first-rate clinical hypnotist. On this day he began with a speech about the need to “be completely open and level,” because if Candy wasn’t or if she didn’t think she could be, the interview was over. “No, there’s no question about that,” she assured him.

“All right,” he said. “I want you to start and tell me about what happened that day.” Candy reluctantly began with vacation Bible school and ended up telling Fason everything about the morning of Friday, June 13—more than she had told Crowder, more than Pat knew. Then they talked a long time about control and anger and Candy’s deep-seated unconscious fears.

After a couple of hours, when Fason was sure that he had won his patient’s trust, he decided to try hypnosis. Candy was remarkably susceptible; she went under quickly, and her hypnotic trance was deep. Fason’s smooth, soft voice carried her far under, until her body was totally relaxed; then he took her back to Betty Gore’s utility room. “When I snap my fingers,” he said, “you will begin re-experiencing and relating that time to me as you go through it. One. Two. Three.” He snapped his fingers loudly. “Begin. What’s happening, Candy?” she said nothing; she looked worried. “What’s happening, Candy? You can tell me.” He waited for a response that didn’t come. “What thoughts are going through your mind? I’m going to count to three. When I reach the count of three, your thoughts and feelings will get stronger and stronger—stronger and stronger and stronger—so strong you will have to express them and verbalize them. One. Two. Stronger and stronger, so strong you will have to get them out. Three. Let them out. What’s that you’re feeling, Candy?

“Hate.”

“Okay. You hate her. Express your feelings. Stronger and stronger.” Candy whimpered. “You hate her,” repeated Fason.

“I hate her,” she whispered.

“You hate her. You hate her. Say it out loud.”

“I hate her.”

“Louder.”

“I hate her. She’s messed up my whole life. Look at this. I hate her. I hate her.”

“When I count to three I want you to back up in time again, Candy. I want you to go back in time to where she’s shoving you. You’re in the utility room, and she shoves you. Just relax. One. Two. Three.” Candy whimpered and moaned softly. “What is happening? Go through it. The feeling is very strong. One. Two. Three. She’s pushing you.” Candy moaned again. “What’s she going to do? What’s happening? Tell me. What is it?”

Candy tried to say something.

“What? Louder.”

“I won’t let her hit me again. I don’t want him. She can’t do this to me.”

“The feelings are getting stronger,” said Fason. “Stronger.” Candy squirmed on the couch but didn’t respond.

Fason made her go deeper into the past, asking her to back to “the first time you ever got mad. Do you recall ever being that mad before? Do you recall it?” No response. “When you were little. Let’s go back, back in time. Let’s get in the time machine and go way, way back in time. Back when you were little. One. Back, back in time. Two. Three. The time machine stops. How old are you, Candy?

“Four.”

“Four. Tell me about it. What made you so mad?”

“I lost it.”

“What did you lose?”

“Race.”

“You lost the race?”

“To Johnny.”

“Do you like Johnny?”

“He beat me.”

“What did he say when he beat you?”

No answer. “How did you feel?”

“Mad. Furious.”

“What are you going to do?”

“I’ll break it.”

“Break what?”

“The jar.”

“How did you break it?”

“I threw it against the pump.”

“Are you scared?”

Candy nodded. “My mother took me to the hospital.”

“What did your mother say?”

“Shhhh.”

“Did what?”

“Shhhh.”

“What did she say?”

“Shhhh.”

“When I count to three, your feelings will be stronger and stronger. One. Two. Three. What are you seeing?”

“I’m afraid.”

“What are you afraid of? Are you afraid of being punished for your anger? Is that what you’re afraid of?”

“It hurts.” She rubbed her hand across her head.

“Your head hurts? Where does it hurt?”

“I’m scared. I want to scream.”

“When I count to three, you can scream all you want to. One. Two. Three.” She shivered but made no sound. “Just kick and scream all you want to,” said Fason. “It’s okay. It’s okay to do it.” Candy shrieked, an eerie wail that could be heard through two walls of Fason’s office. “It’s all right,” he said. “Just kick and scream all you want to.” Candy was breathing hard. “How did you feel when she said shhh?”

“I’m afraid and I’m going to kick and scream.”

“When I count to three you’re going to kick and scream all you want to. One.”

“I can’t.”

“Yes, you can. Two. Three. Kick and scream all you want to.”

She screamed even louder. “It hurts,” she yelled, and then screamed again.

As soon as she stopped, Fason thought it wise to bring her out of the trance. It would take more interviews to sort out the details of Candy’s childhood trauma, as well as of the terrible and fatal struggle between Candy and her friend Betty, but by the end of that first session, Fason had done what Crowder had asked him to do. He had found—in the memory of her mother’s perhaps ill-advised discipline at a painful moment—the trigger of Candy Montgomery’s rage.

A Dance of Death

By October 1980 Crowder was ready for the trial. When it started, he stunned everyone with the declaration that his client would plead self-defense. And when Candy was called to the stand as a witness, seats for the day’s proceedings were hotter than season passes to Dallas Cowboys games.

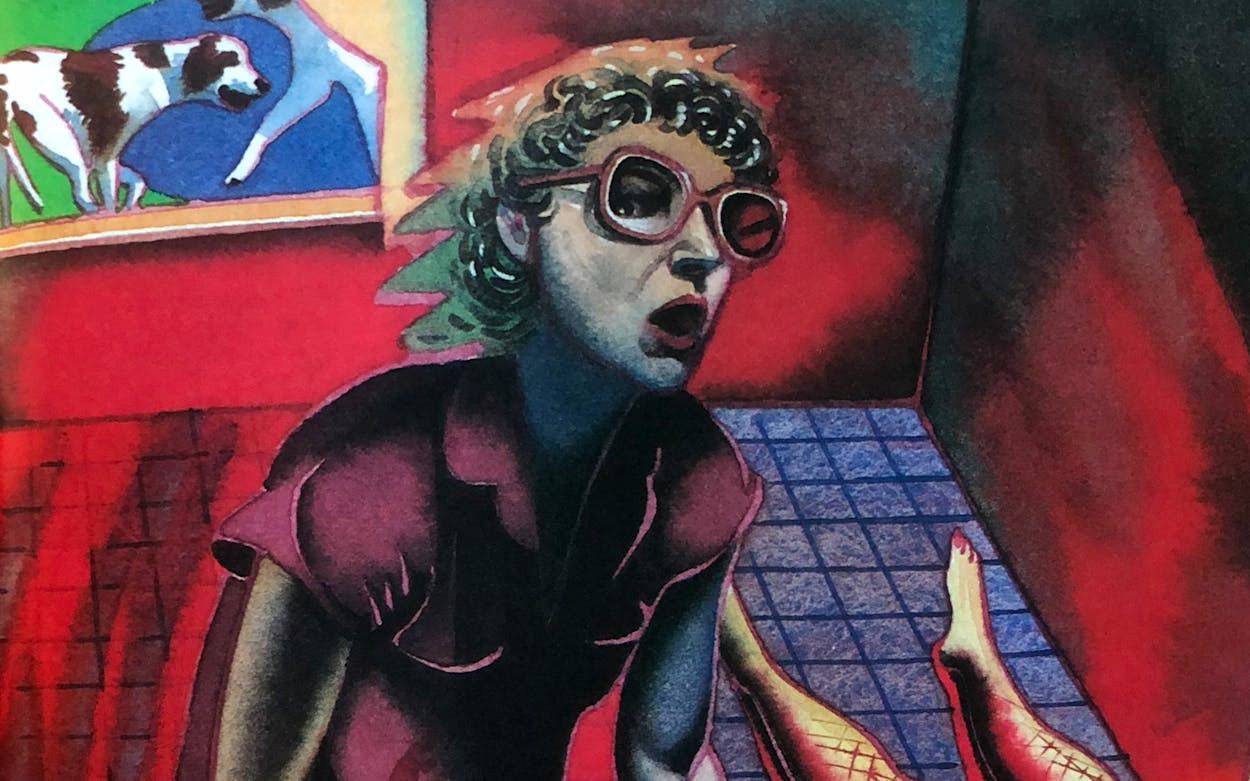

In the courtroom Candy looked sober and matronly; Crowder had been explicit about what she was to wear. Her hair was short and wavy. She wore earrings and a loose-fitting blue dress, dark and subdued, with a hemline well below her knees. Over her shoulders she draped a white woolen sweater. In spite of Crowder’s coaching, though, Candy was less than a model witness. Her voice was clipped and nasal, her manner cool. As Crowder questioned her—about her children, her upbringing, her community and church activities, her friendship with the Gores—Candy gave short, functional answers. She sounded like a stuffy schoolmarm, overenunciating her sentences and banishing all emotion from her voice.

The story she told had not sprung spontaneously from her conscious memory. Two months before the trial, most of the facts of the case—what had actually happened inside the utility room—remained unknown. Dr. Fason had changed all that with three long, wrenching hypnosis sessions, and after each one Candy had repeated the events of the thirteenth to Crowder. Whenever her conscious story conflicted with her unconscious story, Crowder confronted her with the lie and forced her to admit the facts she would rather have forgotten. From those sessions, the best possible reconstruction of the killing of Betty Gore emerged.

She wasn’t expecting Candy until noon, so when Betty responded to the polite knock that morning, she looked annoyed. No doubt she had just sat down to rest for the first time that day after putting Bethany into her crib for her midmorning nap. She had probably hurried to the door so the noise wouldn’t wake the baby. Betty held a half-finished cup of coffee, and from behind came the muffled sounds of The Phil Donahue Show. Since she hadn’t intended to go out that day, she was dressed for housework: tight-fitting red denim shorts, a yellow short-sleeved pullover, and sandals. She opened the front door halfway and peered out.

“Betty, I have a special favor to ask you.” Candy was not long on salutations, but no one minded her abruptness; the friendliness in her eyes and her smile was greeting enough. “The girls wanted Alisa to go see the movie with us tonight, and I told them that if it’s okay with you, it’s okay with me, and I’ll be happy to take Alisa to her swimming lessons to save you the extra trip.”

“That’s okay,” Betty said. “Come on in.”

“I thought it would be,” said Candy, “and so I just ran down from Bible school to get Alisa’s swimsuit.” The two women walked into the living room, which was dominated by a large playpen in the middle of the floor, with toys and children’s books strewn around it.

Betty switched off the television and went to the kitchen. “Want some coffee?”

“No thanks.” Candy sat next to the sewing machine, where she noticed that Betty was making something out of yellow cloth. Betty came back and sat on the other side of the small table. She seemed tense, as though she were anxious for Candy to leave. “So where’s Bethany?” Candy asked.

“Bethany got up very early today, and she just went back to bed.”

“Oh, no!” said Candy, frowning. “I wanted to play with her.”

“Candy, if you’re going to take Alisa to her swimming lesson, remember that she doesn’t like to put her face under water,” Betty said. “So when she does put her face under, be sure to give her peppermints afterward. That’s the reward we use.”

Betty was loosening up a little, as though the small talk was a welcome interruption to the morning chores. They chatted awhile, then Candy glanced at her watch. “Well, it’s getting late and I have some errands to run. You want to get me Alisa’s suit?”

Betty didn’t stir from her chair. Her face was blank; her eyes were unfocused. “Candy,” she said calmly, “are you having an affair with Allan?”

Candy was stunned. “No, of course not,” she answered, a little too quickly.

Betty squinted, and a steeliness crept into her tone. “But you did, didn’t you?”

“Yes,” Candy said, quietly now, “but it was a long time ago.” Candy was still, and her eyes avoided Betty’s. Betty said nothing, staring past Candy’s head, transfixed, sullen. “Did Allan tell you?” Candy looked into Betty’s face for some sign.

“Wait a minute,” Betty said. She rose abruptly from her chair and walked through the open door of the utility room and out of sight. Candy wondered how recently Betty had found out. Candy also realized, with a quiet panic, that she had nothing to say to her.

After a few seconds Betty reappeared in the doorway, her face tense. She was clutching the curved wooden handle of a three-foot ax, the kind used for chopping heavy firewood. Her stance, oddly enough, wasn’t very threatening, since she held the ax clumsily, away from her body, the blade pointed at the floor. Candy was more worried about what Betty would say more than what she would do. Candy stood up but didn’t move from the chair. “Betty?”

“Well, don’t see him again,” Betty said. It was an order.

“Under the circumstances,” Candy said, “I think I’ll just bring Alisa home and drop her off right after Bible school.”

“No,” said Betty harshly. “I don’t want to see you anymore. Just keep Alisa and take her to the movie, because I don’t want to look at you again. Bring her home tomorrow.” Betty laid the ax against the wall, just inside the living room, and walked past Candy into the middle of the living room. “I’ll get a towel from the bathroom,” she said, over her shoulder. “You get Alisa’s suit off the washer.”

All Candy wanted to do was get out of the house because she suddenly had a sick feeling in the pit of her stomach. As she took the swimsuit off the washer, Betty reappeared behind her. “Don’t forget Alisa’s peppermints.” The tone was softer now, more reassuring. The two women met at the utility room door, and Betty handed the towel to Candy.

“That’s okay,” Candy said. “I have some peppermints at home I can give her.”

Betty reached into a bowl of candy by the fireplace. “I’ll give you a few of these anyway.” As Candy stuffed the swimsuit and the towel into her handbag, Betty gave her the handful of candies, and she dropped those in as well.

When Candy looked up at last, Betty was staring at her, but her expression was no longer one of rage. Her face was full of pain. Candy thought of how Betty would cry after she left, and she felt a stab of conscience. Both women hesitated, as though something important would be settled by the tone of the parting. Reflexively, clumsily, Candy placed her hand on Betty’s arm. When she spoke, her voice dripped with pity. “Oh, Betty, I’m so sorry.”

All at once Betty’s rage erupted. She flung the hand from her arm and shoved Candy backward into the utility room. Betty grabbed the ax resting by the doorway and rushed in after her, holding it like a weapon, diagonally across her chest. The blade was pointed at the floor. “You can’t have him,” Betty screamed, crowding Candy. “You can’t have him. I’m going to have a baby, and you can’t have him this time.”

“Betty, don’t,” said Candy, putting her hands on the ax as Betty moved in. “This is stupid. I don’t want Allan.” For a moment neither woman moved. They gripped the ax firmly, their eyes locked. Then Betty began to jerk the ax, trying to control it. “Betty, don’t do this,” Candy pleaded. “Please stop.”

“I’ve got to kill you.” Betty spoke slowly, with impersonal finality.

As they grappled for control, Betty wrenched the ax violently and jerked it upward. The flat side of the blade slapped against the side of Candy’s bobbling head. “Betty, what are you doing?” Candy stepped backward, farther into the utility room, and grabbed her head with her hand. “Betty, stop.” Candy looked at her hand; it was streaked with blood. Then she looked back at Betty and saw her raising the ax blade over her head, almost to the eight-foot ceiling, as though to smash her with a single powerful blow. Candy screamed at the top of her lungs, a high-pitched, pleading sound, and jumped sideways into a cabinet, spilling books and knickknacks onto the floor.

Even though Candy had no place to hide—Betty was between Candy and both exits—the ax missed her entirely and landed harmlessly on the linoleum. The blade made a dull thud, bounced once, and sliced a gash in Candy’s toe. Just as it did, Candy grabbed the blade, wrapping her fingers around the thick heavy metal. Her pleading now turned to anger. She said no more.

The exaggerated blow and the drawing of blood unloosed the surging fury of both women. As soon as Candy grabbed the blade, Betty started shoving and jerking the handle. But Candy held on tightly, and the struggle degenerated into a wrestling match. Betty thrust and jabbed the ax and Candy’s body, kicked at her legs, kneed her in the thighs. Candy responded by trying to jerk the handle out of Betty’s hands. From a distance, nonsensically, came the frenzied, high-pitched barking of dogs. Betty moved her hands up the handle, trying to get leverage. Finally she bit Candy on the knuckle. With her head bent, Betty was off balance, and Candy shoved the ax against Betty’s body with all her might. Betty reeled backward and fell against the door of the freezer, her feet slipping a little on the linoleum. Candy didn’t hesitate. As Betty struggled to regain her balance, her body facing away, Candy brought the ax up with both hands and brought the blade down on the back of Betty’s head.

The blow resounded with a hollow pop, like a cork coming out of a wine bottle, and then blood gushed across the back of Betty’s neck. Candy dropped the ax, jumped away from Betty, and felt time shift into slow motion. Betty began to slump toward the floor, blood pouring out of her skull, but she continued to struggle to her feet. Terrified by the blood and the certainty that she had just killed her, Candy bolted for the living groom door, but an eternity seemed to pass as she tried to reach it. She finally put her hand on the knob, started to pull—and Betty slammed her body against the door.

Candy looked up and saw blood spreading across the side of Betty’s face. Betty picked up the ax again, like some nightmarish vision of a corpse that stalks its killer. Tears spurted from Candy’s eyes. The barking of dogs, wolfish and primitive, grew louder. “Let me go, Betty, please Betty, let me go.”

Betty’s voice came from a thousand miles away: “I can’t.”

Candy grabbed the ax again, and the women began a macabre dance around the utility room, once again jabbing and pushing with the ax that hung between them. Betty’s head dripped blood until the linoleum was slick with crimson. They circled endlessly, one losing her grip, then regaining it before she could be shoved away. At one point, when Betty bumped against the freezer again, Candy removed a hand from the ax and grabbed the knob of the door to the garage. She pulled the door open a few inches, but Betty managed to shove her away, slam it shut, and push in the lock on the knob. They kicked each other as they jockeyed for position. Their shoes squeaked on the sticky red floor, and above the steady electrical hum of the washing machine, they grunted and breathed heavily. Betty grabbed Candy’s hair with one hand. Then Candy slipped on the blood and went down hard directly in front of the freezer. As she did, Betty tried to raise the ax but, growing weak from loss of blood, couldn’t get it up in time. Candy tackled her by one leg, and Betty sprawled forward, almost on top of Candy. By the time they were upright again, the ax was between them and they fought over it from sitting positions. Candy shoved Betty hard, jumped to her feet, and lunged at the garage door, but the knob wouldn’t turn. She pivoted as Betty moved toward her. “Betty, don’t,” she said. “Please let me go. I don’t want him. I don’t want him.”

Betty’s eyes flared in a final paroxysm, but her reply was eerily restrained. Placing one finger to her lips and gripping the ax with her other hand, she breathed from somewhere deep in her throat: “Shhhh.”

The susurration echoed through Candy’s subconscious like a psychic alarm. She grabbed the ax and used it aggressively, pushing the handle against Betty’s legs. Through a window came the hysterical canine sounds, desperate now, the barking and howling of frightened creatures. Candy jerked the ax and then leaned backward with all her might, wrapping both hands around the blade. The handle was covered with blood, and when Betty tried to pull just as hard, as though in a tug-of-war, her hands slipped off and she plunged backward into the room. She wouldn’t stay down, though. She lunged toward Candy, but Candy had time to raise the ax and bring it down with all the adrenaline-fueled strength she could gather. There was no pity or remorse or conscience now. Candy destroyed Betty out of pure, unadulterated hate—anger over what this woman had done to her, rage that now her life might be changed because of this stupid woman. Candy stopped at the point of utter exhaustion. There were, in all, 41 chop wounds. Forty of them occurred while Betty Gore’s heart was still beating.

The huge courtroom was silent. Candy Montgomery’s voice had barely risen above the traffic noise from the square. Crowder continued his questioning, but Candy was lapsing into her monotone again. While describing the struggle, her cheeks had trembled and she had sobbed silently. But now she recovered her composure. Crowder feared that her testimony seemed too rehearsed. “When you went over there,” he said, “did you mean to kill her with that ax?”

“No.”

Crowder picked up the ax and placed it on his right hip. Time for a bootleg play, he thought. “But you did kill her with the ax, didn’t you?” he said as he walked back toward the witness box.

“Yes.”

“This ax right here—“

“Don’t make me look at it.”

He grabbed the ax with both hands, brought it into full view, and thrust it toward Candy’s face.

“Don’t!”

“You killed her with this ax right here, didn’t you?” Pat Montgomery could hear Candy’s scream in the witness room, thirty yards away. Candy burst into tears and seemed to rise out of her chair. “You killed her with this ax right here, didn’t you?”

“Yes,” she said, so he would take it away.

One of the woman jurors dabbed at her reddened eyes with a tissue. Another squirmed in her seat, offended by the cheap trick. She, too, wondered why Candy seemed so cold and impersonal, but she also felt an odd sympathy toward her. Her story hung together; it didn’t seem whitewashed. But how can you be sure? She wanted the prosecutor, Tom O’Connell, to be tough, to pry open every part of the story, to find the one lie in it that would make it all come apart.

Crowder led Candy through the rest of her day and had her admit all the cover-ups and evasions of the following week, as she had tried to avoid detection.

After a ten-minute recess, O’Connell drew a deep breath and plunged in. This is what he had been afraid of. Candy was intelligent, attractive, direct, she handled herself well, and she used the best possible explanation, the “I freaked out” excuse. He would probe at her story, trying to pick out the discrepancies.

There are prosecutors who froth at the mouth like mad dogs and wave their arms and work themselves into a frenzy of moral outrage, but O’Connell wasn’t one of them. He stuck to his original plan and tried to expose the cracks in her story. He asked Candy to repeat her account of what happened in the utility room, but with much less detail. She didn’t hesitate, and there were no contradictions. She even added small details, like the location of the peppermint candies in a glass bowl on a shelf next to the fireplace. It was the kind of thing a bald-faced liar wouldn’t know. O’Connell’s questions wandered from place to place, from the utility room to a friend’s divorce and back to the cover-ups. He emphasized that a year-old baby had been left alone by this woman who prided herself on her motherhood. He pointed out Candy’s repeated lies to her friends. And then, abruptly, he stopped.

“You many stand down,” said the judge.

Candy’s testimony ended on a Friday. The following Wednesday, the jury heard the final arguments and reached its verdict that same afternoon. Candy Montgomery was found not guilty.