This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I first met Sam Corey during a time that must now seem like the high point of his life. His massage parlor in San Antonio, the Tokyo House, was doing well, so well in fact, that he had expanded to Irving and was engaged in a legal fight to open parlors in Dallas. At the same time he was running for mayor of San Antonio. His campaign had no importance politically and its main effect was that it produced a great amount of publicity for Sam. He adopted the slogan, “Let’s put the nitty gritty before the city,” had several masseuses run for city council on the same ticket with him, and promised voters that, if elected, he would hire a girl in hot pants to chauffeur the mayoral limousine. Sam also took a stand on such genuine issues as the completion of a freeway running through town and construction of a domed stadium. He even, in his first press release, claimed that in order to finance his campaign, he would mortgage everything he owned and live in poverty, just as he had “successfully lived in the days of monastic existence as a Brother of Mary.” All this, the whole campaign, was a mixture of hokum and bombast, of a need to be taken seriously combined with a perverse delight in acting not at all serious. Sam wanted to be mayor and had a few ideas, not many but a few, of things that needed to be done in San Antonio. But apparently, the real reason he wanted to be mayor was not so much to get things done as to cruise around town in a limousine driven by a girl in hot pants. Sam assumed the voters of San Antonio would find this idea endearing.

I found it, if not exactly endearing, at least intriguing and went to San Antonio to write a story about Sam, his massage parlors, and his political shenanigans. Never has a reporter had a more willing subject. When I returned a few days later with a photographer, Sam, who weighed over 300 pounds at that time, immediately agreed to my suggestion that he pose getting a massage. He stripped off the tentlike dark blue suit that he had worn especially for this session. Then, in only a pair of voluminous white boxer shorts that began at his rib cage and extended in yards of billowing white cotton below his knees, Sam crawled up on a massage table and lay there, giggling as foolishly as a baby in its crib, while a team of his masseuses kneaded his ponderous belly and rubbed his stubby legs and the photographer circled the scene clicking off shot after shot.

The candidate for mayor lying on the massage table, moaning in lugubrious pleasure, seemed incapable then of anything beyond low foolishness. But while Sam was busy posing for my photographer, two men were waiting for him in his office. One of them was Dr. Charles Guilliam, and he and his associate were there to sell Sam a credit-card service for his massage parlors. This Dr. Guilliam was neither a psychologist as he claimed nor was his name Guilliam. He was Claudius James Giesick, a 26-year-old rip-off artist, con man, and pathological liar, who less than a year later would take his bride of a few weeks, a young masseuse Giesick had insured for $351,000, to a lonely road outside New Orleans and push her under the wheels of a speeding automobile.

Her skull and hips were brutally crushed, and yet she lingered for nine hours before she died. After a five-day trial, a New Orleans jury took only twenty minutes to decide that Sam Corey was the man who drove the car. Whatever cause far in the past or deep in their psyches made Corey and Giesick capable of conceiving and carrying out such a scheme, the direct series of events that led to the murder began when Sam, rosy-skinned from his massage and full of himself from being the center of attention for most of the afternoon, pulled his blue suit back over his boxer shorts and went into his office to talk about credit cards with this man posing as Dr. Guilliam.

I have seen Sam only twice since then. Once was a casual visit at the Tokyo House several months before the murder; the second was at Angola State Prison in Louisiana where Sam now waits on death row. Giesick, who testified against Sam in return for a lesser sentence, is serving his 21 years in another part of the same prison.

Angola is deep in the backwoods of Louisiana, not far from the southwest corner of Mississippi. The road that leads to the prison curves past ramshackle cabins, a logging mill, and a single tiny settlement grown up around a service station, before it dead-ends abruptly at the prison gate. Inside, the prison is all cement floors and pale green walls; my first impression was that life there would be rather like life locked inside a high school lavatory. A Cajun guard led me through barred doors that he opened and locked behind us and down a short hallway and through another set of doors to death row. The guard motioned me into a long, narrow V-shaped room with nothing in it but two metal folding chairs. After a few minutes, another guard brought Sam in. He was handcuffed to a thick leather belt which went around his waist and buckled in back. As the guard unlocked the handcuffs and unbuckled the belt, Sam looked over at me. He had not known until the guard had come to get him that I was coming to visit, and the news had obviously cheered him up.

Sam has always maintained his innocence. Just before my visit Giesick had told reporters that he had lied on the stand and related a completely different account of his wife’s murder, one that didn’t implicate Sam at all. Giesick’s changing stories had given Sam new hope that he might be released and spared the electric chair. Seeing me now, Sam immediately assumed that I had come to help him. The look in his eyes as he gazed toward me was positively beatific. “Greg, I can’t believe it,” he said. “It’s wonderful to see you.”

“It’s good to see you, too, Sam,” I said, but I was feeling more than a little uncomfortable. Sam assumed I was there to write what he called the real story, but I had no way of knowing whether the real story as I saw it would help Sam or not. I tried to mention this a few times but my small warnings were washed away by the torrent of Sam’s enthusiasm for seeing me and his desperate hope for himself.

He looked miserable. He had lost, he told me, more than 150 pounds and now weighed 185. Instead of looking trim, however, he looked deflated. Skin hung in slack folds about his surprisingly small frame. His eyes were deep, black holes in a rather large head. He wore a T-shirt, blue-black gabardine slacks, no socks, and black brogans that were now, since he’d lost so much weight, far too large for him.

He smoked a small pipe with a curved stem. He would light it, take a few puffs, let it go out, then light it again. He kept all his burnt matches in a neat pile beside him so as not to litter the bare floor of the room we were locked in. Frequently as we talked Sam would rise from his chair, shamble over to the guard who was sitting just outside the door, and explain to him the important nuance of something he had been telling me. “No kidding,” the guard would say patiently and I could tell that he had had to listen to Sam’s story many times. Then Sam would shamble back to his chair and, distracted now, fiddling with his pipe, ask me, “Where were we? What were we talking about?”

He stuck to the same story he told at the trial, that when the girl was run over he was in his motel room with a prostitute named Linda whom he had met outside a massage parlor on Canal Street earlier that afternoon. Linda has never turned up and that, to say the least, put a crimp in his defense. Sam says he said good-bye to her in the parking lot of a Holiday Inn and hasn’t seen her since. “I’d never have been with her at all,” he told me, “if I’d known I was going to have to explain to the whole world what I was doing.”

A television blared in the background. At one point, Archie and Edith singing “Those Were the Days” echoed down the cellblock. “It’s two o’clock,” Sam said. “All in the Family.” He went on to say how bored he was, that it wouldn’t be so bad except for the boredom. He gets out of his nine-by-twelve cell only one hour every day so he can take a shower.

“If any good has come of this,” he told me, “it’s that this whole experience has brought me closer to God.” He receives literature and letters from the members of the Full Gospel Business Men’s Fellowship. He keeps a small altar in his cell, and a priest regularly hears his confession. Otherwise he is a debilitated man, desperate for the sympathy of anyone, pleading his innocence while the weight of his sentence pushes him farther and farther out of touch with reality. Just before I watched him get locked in his handcuff belt and led away toward his cell, he said to me, “But you know the worst thing about all this?” And without waiting for me to reply, he answered his own question, “It’s ruined a perfectly beautiful city for me. New Orleans. I’ll never go back there again.”

But later, driving back to New Orleans from the prison, I remembered one moment with Sam different from the rest. He was telling me how he’d met Linda outside the massage parlor. He’d given her some money to wait for him while he had his massage. “I had a very good massage,” he said. And his whole countenance, until then very serious and businesslike, changed completely. A wicked gleam appeared in his eye and, smiling and flushed, pleased with himself and giving me conspiratorial winks, he said, “I got a local there, too.”

I knew what a “local” was. That is massage parlor jargon for a masseuse masturbating her client. But I didn’t understand why this moment remained so vividly in my mind or why it seemed so revealing of Sam or what it had to do with murder.

Patricia Ann Albanowski, the masseuse who would be run over and killed early one foggy morning in New Orleans, was a girl who pursued love. She grew up in New Jersey, but in September 1972, when she was 24, she left her parent’s home and moved to Dallas. She had come halfway across the country after a dark and handsome pharmaceuticals salesman named Roger. She had a broad flat face with rather thick features which she tried to cover with too much make-up. On the other hand, she had long, slender legs, graceful movements, pretty strawberry blond hair, and a pleasant, if slightly goofy, disposition. Roger indulged her for a while.

They may or may not have been married. Trish later told neighbors different stories. Sometimes she said that she had never been married, other times that she had, and still other times that she had been married twice. Whatever their legal status, she moved in with Roger in a large apartment complex in suburban Richardson. She worked at various jobs, in a food-processing plant for a while, in a carpet company. One day she came home to discover that Roger had moved out. About the only thing he left behind was the message that she could find the mailbox key in the manager’s office.

Whether for lack of money or lack of inclination, Trish didn’t return home, leave Dallas, or even move out of the apartment. She still had her job at the carpet company but was so alone and friendless that she was forced, since she couldn’t afford the apartment by herself, to advertise for a roommate in the newspaper.

Luckily, a girl who turned out to be pleasant and dependable answered the ad. When she came to see the apartment for the first time, Trish, instead of telling her potential roommate about the rent or the living arrangements or asking her any question about who she was or what she did, immediately began talking about Roger. She didn’t call him by name but said that a guy had just moved out and left her all alone and that he had been in pharmaceuticals and now she was very sad. Trish talked on and on and her potential roommate didn’t know what to say. She thought it odd enough to have a few second thoughts before finally moving in. But the explanation was simple enough—Trish didn’t have anyone else she could talk to.

The roommate soon discovered about Trish what her neighbors and her succession of bosses always discovered, too. She was a cheerful, good-hearted, sweet girl, but hare-brained and empty-headed, someone so bewildered by the world around her she seemed to be living in a fog. She could not hold on to a job. Eventually even her boss at the carpet company, a man who liked her personally more than many people did, finally had to let her go. He could afford only one girl in his office and Trish, despite her best intentions, had an aggravating tendency to work at her desk all day and leave everything more confused than when she started. Around the apartment complex she became an object of pity. Her neighbors told each other they felt sorry for her. They also agreed that she was a little strange, an impression that was most strongly reinforced when Trish was trying hardest to make friends. She would knock on someone’s door and start talking to them on and on in a vague and confused ramble; she would lurk behind the floor-to-ceiling window at the front of her apartment and make what she hoped were funny faces at the people walking by; and she would stand at her kitchen windows with the curtains only inches apart and stare, sometimes for more than an hour, into the identical kitchen window of the identical apartment next door.

She made no secret about what she wanted, although it was obvious to everyone anyway. She wanted a husband or, lacking that, a man. She attended mass regularly, knew how to keep her apartment clean, liked trying to fix it up to look nice, could cook some, and enjoyed playing with children. But these wifely qualities didn’t seem to appeal to the men she attracted. They came and went, a long string of them after Roger left, and none of them stayed with her for very long. Some were unsavory; one threatened to disfigure her and she lived the next weeks in extreme terror.

In the fall of 1973, about a year since she had come to Texas and nine months since Roger had left, she told the managers of the apartment complex that she was going to take a second job. That came as no surprise in itself since, needing money badly, she had recently sold some of her furniture to people at the complex for absurd prices—$30 for a nearly new console television. She told her neighbors, depending on her mood, that she was working as a model or as a hostess in a club. In the summer she lost her job at the carpet company, and after a brief stint at a food-processing company, she fell back on her new work for her total support. The only person who knew what she was really doing was a bachelor who lived in the apartment complex. She gave him a book of matches from her new place of employment: the Geisha House of Massage. Trish was neither a model nor a hostess but a masseuse. She began to keep very late hours and frequently arrived home with different men. When the bachelor asked her about one of the men he’d seen leaving her apartment, she replied, “Oh, him. He’s a client.” And the bachelor assumed she meant him to know exactly what she had implied.

Dallas had an ordinance that prohibited masseurs or masseuses from massaging anyone of the opposite sex, as did many of the suburban towns surrounding the city. Massage parlor operators tried to have the law declared unconstitutional by the courts, but while they were fighting that legal battle, which they were never able to win, they established their businesses in unincorporated county areas in the environs of Dallas. The first to arrive was Sam Corey, who opened his Tokyo House on a street just west of Irving, which is in turn just west of Dallas. Neighbors protested, not wanting what they took to be a den of prostitution in their midst, but their pleas to officials and picket lines outside Sam Corey’s door weren’t able to force Sam to close. On the contrary, the business looked so successful that a man named Jim Floyd opened a competing massage parlor of his own and named it the Geisha House. His first location was just outside Irving not far from Sam Corey’s place. He soon opened a second parlor southeast of Dallas near Seagoville.

The Irving parlor may have been somewhat better, but the Seagoville parlor, the only one still operating, is merely a mobile home on cement blocks at the side of a highway access road. Inside two bored masseuses pass the time between customers by playing solitaire. They are surrounded by cheap furniture, dirty carpet, dismal wood paneling, overflowing ashtrays, empty soft drink cans, and half-empty cups of coffee so old the coffee looks solid. Trish worked here. She also worked in the Irving parlor. Whatever it seemed like to her, to anyone else it would seem like a place, even among massage parlors, where one would go only at the very end of the line.

About the time Trish started working full-time for the Geisha House, a man in his late twenties who said he was Dr. Guilliam, a clinical psychologist, became a regular customer of massage parlors in the Dallas area. He was a few inches shorter than Trish and had let himself get just slightly on the pudgy side, but he had a pleasant, open face, an easy and friendly way of talking, and always seemed to have plenty of money. Trish was still unabashedly looking for a man. All the other masseuses knew it; they thought she should have been smart enough to know that a massage parlor was the wrong place to look. Still, Trish wasn’t shy about saying that she wished she could see something more of Dr. Guilliam.

Trish got a call one afternoon from another masseuse who had gone to a meeting with their boss Jim Floyd. She said Floyd was sending a man over and Trish was to give him a complimentary massage. The man turned out to be Dr. Guilliam. He took an immediate interest in her. They spent a long time together that first meeting. He seemed to understand her loneliness. He talked about his work and the money he made from it. She made love with him. After that he kept coming around to see her and, right from the start, began asking her to marry him.

At first she said yes, but then she changed her mind. He was nice and all that, but she didn’t have any strong feelings for him and there were certain things about him that worried her. It turned out that his name wasn’t really Guilliam but Claudius James Giesick. He told her he used Guilliam because he had helped apprehend some gold smugglers and, as protection from reprisals, the federal government had given him a new identity. He said he really was a psychologist; however, he didn’t have an office, and he would disappear suddenly only to turn up again later. Trish had already had too much experience with disappearing men. Still Giesick-Guilliam kept coming around to see her.

Giesick, despite his glib and friendly manner, didn’t seem to have many more friends than she had. The only one she knew about was Sam Corey, the owner of the rival massage parlor in Irving. Giesick had brought Corey with him several times and when Trish decided that she didn’t want to marry Giesick after all, it was Corey who interceded and convinced her that she should. He said that Giesick really loved her and had enough money to take good care of her. She agreed a second time to marry him. At least it would be better than working at the Geisha House.

Nevertheless, Trish didn’t feel completely comfortable with her decision. She went to see her former boss at the carpet company and talked to him about it. He said the man sounded a little suspect and gently asked her if she thought it was a good idea to marry someone she knew so little about. Neighbors at the apartments would occasionally ask her the same thing, but she took these questions as criticisms of her and responded by defending her decision. Only to her bachelor acquaintance did she say that she didn’t love Giesick but that he was nice to her and made a lot of money and that was why she was going through with it.

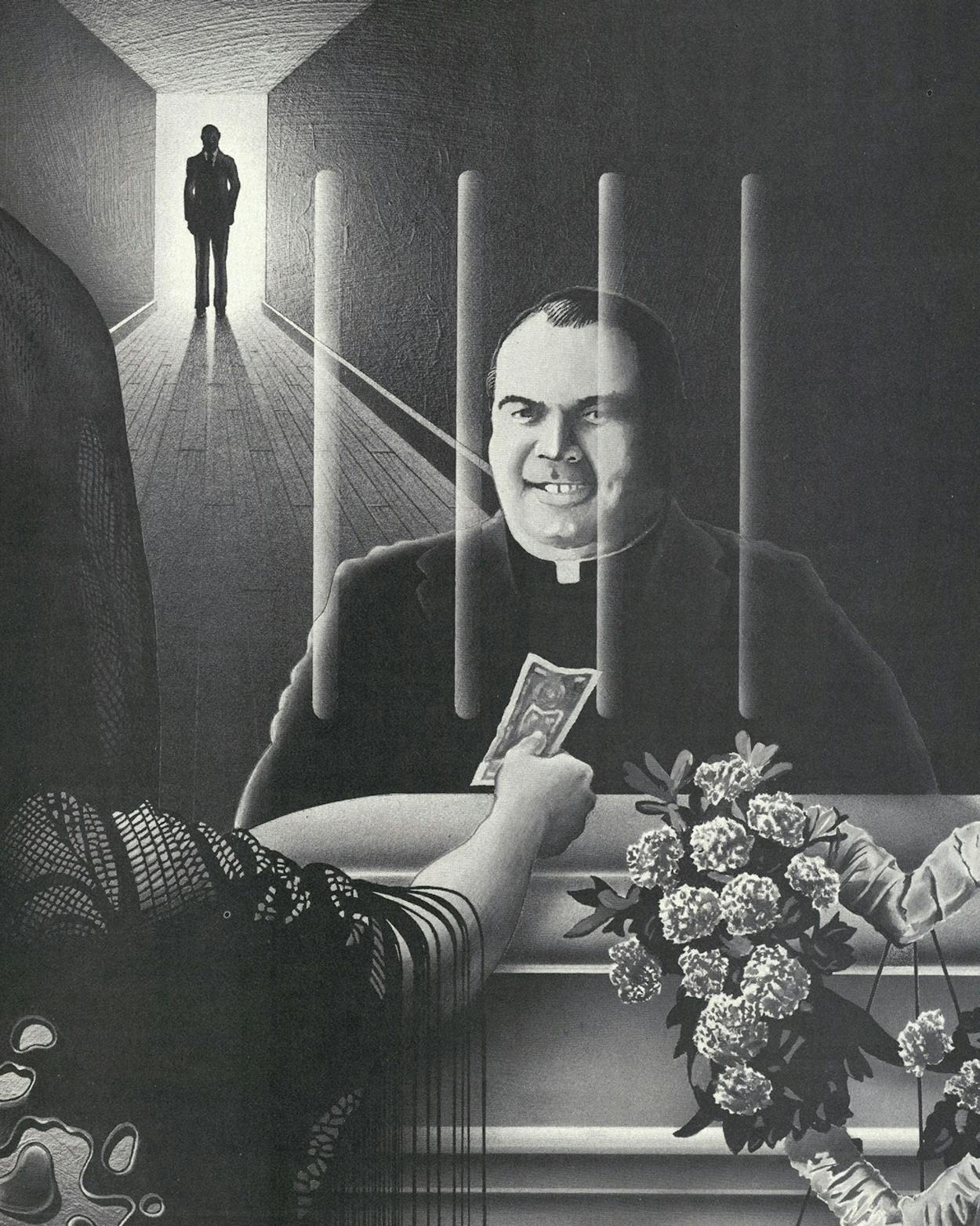

Giesick told Trish that he had been married twice before. Once was to a former Miss Texas who, along with their child, had been killed in a hit-and-run accident. He had been married another time and divorced. That prevented them from being married in the Catholic church as Trish would have liked. It turned out, however, that Sam Corey had once been a novitiate in the Brotherhood of Mary and had now become a pastor in something called the Calvary Grace Christian Church of Faith. His motive in becoming a pastor was no more high-minded than the wish to escape police harassment of his massage parlors. He wanted to claim massage as a religious rite in his church, a rite whose practice would be protected under the Constitution. He had even taken steps to change the name of his business from Tokyo House of Massage to Tokyo House Massage Temple. Even so, Sam Corey had the legal right to perform marriages, and his old affiliation with the Catholic church made him seem to Trish something closer to a real priest than an ordinary minister. On January 2, 1974, he performed the ceremony in Trish’s apartment. Only Sam Corey, Giesick, and Trish were there, although two other names were falsely added to the marriage license as witnesses. After the ceremony, Trish called her parents in New Jersey. “Hi, Mom,” she said. “This is Mrs. Giesick.” The new couple set up housekeeping in the apartment where Trish had been living since she came to Texas.

Before they were married, Giesick had promised that he would buy her a $100,000 house in Richardson and a yacht and take her on a long honeymoon trip. But after the marriage, the first thing her husband bought was life insurance. Losing one wife in an accident had taught him a lesson, he said. He wanted to be prepared in case, God forbid, anything should happen to either of them.

Their marriage had taken place on a Wednesday. The following Friday her husband had an insurance agent call on them at the apartment. The next Monday Giesick bought a $50,000 policy with a double-indemnity clause that covered both him and Trish. It seemed like a rather large policy to her, but her husband was a man who made lots of money and should know how much insurance to buy. When she signed the forms, she wrote “Patricia Ann” and was about to add her maiden name, Albanowski. She got as far as the “A” when she realized her mistake. She drew two lines through the letter and wrote “Giesick” after it.

Then her husband left town on what he told her was a business trip. He gave her a number where he could be reached but it turned out to be the number of an answering service. Trish desperately called Sam Corey and finally managed to reach her husband through him. Giesick told her he would be back by the weekend and she should start checking with travel agencies because they were going to take that trip he’d promised her. They would go to Florida, the Caribbean, home to New Jersey, perhaps to South America. When he reappeared that weekend he was sporting a new dark blue Chevrolet Monte Carlo with a black vinyl roof. He also presented Trish with a St. Bernard puppy as a wedding present.

Sunday afternoon, January 13, her new husband drove Trish out to the Dallas–Fort Worth Airport, which had just opened that day. They were leaving for New Orleans and he thought it would be a good idea to buy more insurance for the trip. He took her to the Tele-Trip insurance booth and asked specifically for the $300,000 annual policy. The woman in the booth explained that $200,000 of the coverage would be on vehicles, common carriers, and scheduled airlines, but the remaining $100,000 would only cover common carriers and scheduled airlines. Giesick immediately asked if that extra $100,000 covered automobile travel. The woman in the booth told him it didn’t and Giesick said that he definitely was not interested in the additional coverage. The woman wrote out a $200,000 policy for Patricia Ann Giesick with Dr. Claudius Giesick as the beneficiary.

It was late in the evening before they were ready to leave. They planned to go to New Orleans first and from there to Florida where they would see Disneyworld and catch a boat for a Caribbean cruise. Trish insisted, although it was getting a little late, on taking the puppy down to the apartment of her bachelor acquaintance so she could say good-bye and let his young son, whom she had always liked, play with the puppy. When she introduced the two men, Giesick, normally so glib and outgoing, was coolly polite, remained in the background, and said very little. It was after nine o’clock by the time they left, but Trish now insisted on showing the puppy and saying good-bye to two girls who lived in a neighboring apartment. Again Giesick stayed quietly in the background. But when the visit dragged on, he interrupted, on this midwinter night, with, “Come on, Trish. Let’s get going before it gets hot.”

The vague unease about Giesick that had bothered Trish before their marriage did not go away. If she had hoped that his strange behavior would change on the trip, she was disappointed. They arrived in New Orleans Monday afternoon and the first thing Giesick did was disappear again. He told her the car, new as it was, was having transmission problems and he needed to see about having it fixed. Their motel was an isolated Ramada Inn far away from the center of the city on a road called Chef Menteur Highway. This road had once been the major thoroughfare entering New Orleans from the east, but when a new interstate opened, traffic on Chef Menteur dropped off drastically. The Ramada Inn and the Quality Inn next to it survived only because several large plants nearby brought in business. A few blocks away there was a shopping center with a grocery store, a service station, and a few small shops, but nothing that was very entertaining. Left alone in the motel, Trish had nowhere to go and nothing to do but play with the puppy.

Giesick didn’t come back to their motel room for more than two hours. He said that he’d had to hitchhike from the dealer where he’d left the car. He acted very restless and upset. They watched television in their room for a while, but still he was restless. About 9:30 p.m. he suggested that they go walk along the highway for a while so they could talk things over. Trish said all right, although she was tired from the long drive from Dallas. It wasn’t a pretty or quiet or easy place to walk. Cars and trucks, noisy and belching exhaust, rumbled past. Their wheels frequently spit out gravel that had spread onto the asphalt from the narrow shoulders. It was dark and Trish and her husband stumbled along the side of the road. They couldn’t really talk—it seemed like a car or truck went by every second—and Trish was soon ready to go back to the motel. But her husband seemed determined to stay out there. They walked up and down the same stretch of road several times before Giesick finally agreed to return to their room.

But he didn’t stay there. He said the puppy needed walking and left her, almost exhausted, alone again in the room. Perhaps a half hour later he came back. He said he’d found a pretty bayou just on the other side of the shopping center down the highway and wanted to show it to her. Reluctantly, tired as she was, Trish agreed to go. They walked the four or five blocks to the shopping center and another hundred yards up a street called Michoud Boulevard. It led past the shopping center to a low four-lane bridge spanning the bayou and on to a new and now, since it was nearly midnight, quiet residential area.

In the parking lot of a service station near the bridge a Chevrolet Monte Carlo, the same year but a different color from the one she and her husband had driven to New Orleans, was parked alone. A police car, lights on and motor running, had stopped next to the Monte Carlo and a patrolman was shining his flashlight into it. They had hardly gotten to the bridge before her husband wanted to take her back to their room again. But once there, he said he needed some time by himself to think things over and went out walking once again. Trish went to bed and her husband didn’t return for several hours.

They slept so late that it was after one o’clock the next afternoon when Trish, alone, wandered into the motel lobby and asked if there was a good place to eat nearby, a place close enough to walk because their car was still in the shop. The only place, other than the motel restaurant, was a combination bar and restaurant across the street. She ate there and went back to her room. Her husband was gone again—he had said he was going to hitchhike to the dealer to see about the car—and she had nothing to do. She spent the time waiting in the room or playing with the puppy on the small lawn just outside their door. Once the phone rang and she answered it, thinking it must be her husband. “Hello,” she said, but whoever was on the other end of the line hung up without saying anything. It could have been a wrong number, but the phone rang several more times that afternoon and each time the same thing happened. She was alone in a strange city, stuck in an isolated motel, married to a man she had known only a month, and now strange phone calls plagued her dull and lonely afternoon.

Her husband returned about six o’clock with the news that their car still wasn’t ready. They sent out for some pizza and spent the evening watching television or, rather, she watched television. Giesick was even more restless than the night before. He took the puppy out for several walks and other times went out by himself. He told her something had come up in his business and he was going to have to catch a plane the next day for a quick trip. He asked her to take some of his clothes to the desk clerk to see if they could be cleaned in time. Then he went out again because, he said, he needed to be by himself and think. She glumly gathered up her husband’s dirty clothes.

It was just before 10:30 p.m. when she took the clothes to the desk clerk. Trish was despondent. She talked to the clerk a little and tried to make a joke about all that had gone wrong since they’d come here on their honeymoon. The brief conversation made her even sadder and, back in the room, she called her mother in New Jersey. Trish talked with her for half an hour. She told her about their difficulties with the car and said her husband was acting so strangely that she had begun to worry about something else—all that insurance Giesick had bought for her.

When her husband returned from his walk, it was well after midnight. Trish didn’t want to be alone in the room anymore, but she was apprehensive about seeing him as well. For the first time, however, he was more like the way he’d been before they were married, more solicitous of her, filled with plans for what they would do together in the future. And he had seen something he wanted to show her. Down on the bayou they’d visited last night was a small family of ducks. They were right there near the edge of the road. The two of them could walk down there, discuss their future together on the way, and then watch the ducks on the bayou.

That wasn’t much of an evening’s entertainment for a honeymoon, but at least it was something. Trish put on a pair of old blue jeans, a red-and-blue- striped cotton jersey, and a heavy white sweater. Outside it was slightly chilly and there was a thick fog. Giesick had a flashlight which helped them see their way, but even with its light, it was very easy to stumble and impossible to see very far ahead.

Still, Trish was feeling excited. The combination of cool, damp fog and her husband’s better attitude helped pick her out of her doldrums and she found the walk down the highway to the intersection and then down Michoud Boulevard more interesting than it had been the night before. With her new enthusiasm, she kept pointing out various things they passed to her husband and kept wanting to stop and examine trees and street signs and store windows more closely. He indulged her for a while but seemed determined that they should get to the place along the bayou near the bridge where he’d seen the ducks. They walked under the overhead lights along the short bridge. The fog, illuminated beneath the lights, was a shimmering, golden mist. Just across the bridge they walked down a short terrace to the bayou’s edge. The grass, wet from the fog, was slippery. It was very quiet, the water making no sound, no one out but the two of them, no lights on in the houses nearby, and, except for an occasional car, no traffic on the boulevard. They spent several minutes down by the edge of the water until finally, when they were somewhat chilled, they began to climb the few slippery steps back up the terrace. During the climb a souped-up car with very loud mufflers drove by. The car was dark-colored and the driver looked very young. By the time they had reached the top, no longer than a few seconds, the car was out of sight, its mufflers a low moan resonating deep in the fog.

Her husband had fallen slightly behind and Trish waited on the sidewalk for a moment with her back to him. Then she started across the street. She had taken only a few steps when hands shoved hard against her back at the same time something tripped her. She sprawled face down in the street. She turned on her side and tried to push herself up on one arm to see what had happened. But a car traveling at high speed came at her out of the fog. One front tire hit her head; a rear tire, her hips. The car drove completely over her and kept on. She tried to lift herself on one arm again, then fell back against the pavement. If she saw anything before losing consciousness, it was her husband coming tentatively toward her.

Young Ricky Mock had just dropped his friend off at home. He was driving back down Michoud Boulevard, his loud mufflers roaring in the quiet night, when he saw the accident. A woman lay bleeding in the road. A man knelt over her. The man flagged Mock down and asked him to call for help. Mock gunned his ’73 Dodge down Michoud, the car’s mufflers roaring louder now, and turned right on Chef Menteur. Eight minutes later there were five patrol cars and an ambulance on the scene.

As ambulance attendants administered to the woman, the man walked over and sat on the curb. He had blood on his hands. An officer named Henderson came over to ask if he was hurt. “No,” he said, “but she’s hurt bad.” Henderson asked him if he could describe the vehicle that had hit his wife. “I think it was a four door, a late model,” the man said. “There was only one person in it and he was dark. I really don’t know what kind of car it was.” Henderson asked if he’d seen which direction the car took when it reached the highway. “No, I didn’t,” the man said. “The car never slowed down. In fact, after it hit my wife it picked up speed.”

The ambulance was leaving by then and the investigating officers, Henderson and his partner Lesage, put the man into one of the patrol cars which would take him to the hospital. Henderson and Lesage stayed behind to take measurements and inspect the scene for whatever additional evidence they could find. The man had given his name as Claudius I. Giesick, Jr. He said he had driven with his wife to the bridge and now his car was parked in the supermarket parking lot nearby. The officers walked over and inspected his car—a 1974 silver-blue Monte Carlo with a black vinyl top. It had no license plates. There was nothing else to help them, no skidmarks, no gouges in the road, no mud samples or other physical evidence of any kind, and no witnesses except Giesick. Henderson and Lesage went on to Methodist Hospital to question him some more.

When they arrived, they saw Giesick in the parking lot outside the emergency room talking with a short, but very heavyset man. The heavyset man had his back to the officers. Giesick waved and walked up to meet them. The heavyset man, even as Giesick walked away, didn’t turn around but stood exactly where he was and kept his back to the officers.

Giesick had apparently regained some of his composure. When the officers asked him if he could remember anything else that might help them in their investigation, Giesick said he remembered more about the car. “It was dark,” he said. “I believe it was a late model. After it hit my wife, I think it took a right at the highway. And I remember one more thing. It had loud mufflers.” He explained that just before the accident he and his wife were standing near the bridge looking at the water. They were getting ready to go back to their car in the supermarket parking lot when she said, “Let’s race back to the car,” and started to run across the street. She didn’t see the car coming which by then was only a few yards away. It didn’t have its lights on. It swerved to try to avoid her but it was too late. The car knocked her to the ground, ran over her, and never slowed down.

The officers took down where Giesick was staying and then left the hospital to join in the search for the hit-and-run car. They stopped numerous cars that night but to no avail.

At 1 p.m. on January 16, a priest at the hospital contacted Lesage to say that Patricia Ann Giesick had passed away at eleven that morning. The officer then tried to call Giesick at his hotel and, since Giesick wasn’t in, left a message for him to come to the district station at 11 p.m. when Lesage came on duty. Instead of coming to the station, Giesick called. He said he was already back in Dallas and left a number where he could be reached.

By now the death was in the news. Reporters called it “New Orleans’ first traffic fatality of the new year.”

The next afternoon Henderson went to the Ramada Inn where the Giesicks had stayed. Giesick had registered under the name of Charles J. Guilliam. At the time of the accident he explained this by saying he didn’t want anyone to know where he and his wife were staying on their honeymoon. Henderson now learned that Giesick had paid his bill with a credit card issued to Dr. Charles Guilliam. The motel clerk had checked the card and found that it was valid. Giesick told the clerk Guilliam was a good friend who had given him the use of the card as a wedding present. Giesick had signed Dr. Guilliam’s name to the bill and then signed his own name below it. Henderson and Lesage turned in their report with the recommendation that Homicide Division question Giesick further and make a more detailed investigation of the accident.

That job fell to Detective John Dillmann, a young, intense, extremely serious investigator with the general size and build of a college halfback. He began by reviewing Henderson and Lesage’s report and interviewing them personally. Dillmann shared their doubts about Giesick but became especially determined in his task after reading a letter the New Orleans Police Department received about ten days after the accident. It was written on behalf of Trish’s mother by her lawyer. From this letter and from telephone conversations with Mrs. Albanowski, Dillmann learned that Patricia had called home only a few hours before her death and said she was worried about the large amount of insurance on her. She had also complained about their car still being in the shop. But Giesick, when he talked with Mrs. Albanowski after Patricia’s death, at first said they had driven to the scene of the accident. When Mrs. Albanowski questioned him about the car being in the shop, he had changed his story to say they’d walked. She didn’t know how much insurance money was involved, but she was extremely concerned that Patricia’s death might not have been accidental.

It is one thing to suspect, as Dillmann already did, that this accident was really a murder. That suspicion combined with his immediate sympathy for Patricia’s parents made Dillmann very determined about his investigation. But it is another thing, sympathy aside, to find whether those suspicions are true, and still another to develop the evidence to prove those suspicions in court. Dillmann began with very little solid information. He knew two names, Giesick and Guilliam, knew from motel records when Patricia and her husband arrived in New Orleans, and knew from Mrs. Albanowski her daughter’s address in Richardson, the date she and Giesick had married, and the make of their car.

Beginning with the car, he canvassed Chevrolet dealers in the vicinity of the motel and discovered the one where Giesick, using the name Dr. Charles Giesick, had taken his Monte Carlo on January 14, the day he and Patricia arrived in New Orleans. Giesick claimed the car had transmission problems, but the mechanics found nothing wrong with the transmission. They made a few minor repairs and called Giesick. He picked up the Monte Carlo shortly after 5 p.m. the next day. Yet, Dillmann noted, later that night Patricia had complained to her mother that their new car was still in the shop.

Dillmann returned to his desk at the station and soon received a call from a representative of the Farmers Insurance Group who wanted to talk to the officer investigating the accident. One of Farmers agents had just contacted the home office. This agent had sold the Giesicks a $50,000 policy with a double-indemnity clause and Giesick had recently registered a claim to collect the $100,000 for Patricia’s death. This information confirmed Mrs. Albanowski’s statements about the large amount of insurance on her daughter.

Dillmann had been assigned to the case on a Tuesday. The following Saturday, February 2, he flew to Dallas hoping to question Giesick. Unfortunately, Giesick had disappeared, but Dillmann took the opportunity to interview Patricia’s neighbors. He learned that she had come to Texas about a year and a half earlier and had known Giesick only a short time before marrying him. She had worked at several jobs, and according to one neighbor, had recently been working as a masseuse in “one of Sam Corey’s places.”

Dillmann was unfamiliar with this name and ran a routine check on it. Corey turned out to be well known to the Dallas and San Antonio vice squads because he owned massage parlors in both places. He lived in San Antonio but flew to Dallas almost daily. His only real trouble with the law, however, was recent. Although free on bail, he was under indictment in Dallas County for the theft of some massage tables from another parlor. On Monday morning, checking with the Bureau of Vital Statistics, Dillmann learned from the Giesicks’ marriage license, much to his surprise, that the presiding pastor had been the “Rt. Rev. Dr. Samuel C. Corey” of the Southwest Calvary Grace Christian Church, a church not registered in Dallas County.

Still, assuming Corey was actually ordained, there was nothing wrong with performing what appeared to be a legal marriage. Corey’s involvement was peculiar and suspicious, but certainly not yet incriminating. For that matter, the same might be said, with only slightly less justification, about Giesick. But that afternoon Dillmann received a call from a representative of the Mutual of Omaha Insurance Company. They had written a $200,000 accident policy on Patricia Giesick. The insurance official suggested that he take Dillmann to the Dallas–Fort Worth Airport so he could interview the employees who had sold the insurance to the Giesicks. These interviews, which Dillmann conducted during most of the following day, revealed that Corey was involved in aspects of the case rather less religious than the rites of holy matrimony.

Dillmann talked with four employees of the Tele-Trip Company, a branch of Mutual of Omaha, which had issued the $200,000 policy on Patricia. From their statements he learned that two men had first come to the Love Field booth on January 10. One of the men was identified from a photograph as Corey; Dillmann had no photograph of Giesick, but the second man had identified himself by name and he matched Giesick’s general physical description. When they first approached the booth, Giesick was holding a brochure that explained the various types of policies available. He asked about one called Plan C. Corey then prompted Giesick to ask about hit-and-run. After Giesick had asked, Corey again prompted him to say that he was interested because a friend had been involved in such an accident and the insurance company hadn’t paid. Again, Giesick followed the prompting. Then he asked several more questions, all having to do with hit-and-run coverage and all prompted by Corey. He said he was interested in this coverage because he was planning a trip to Africa where the roads were very narrow and he wanted to be sure he was covered.

Two days later, on January 12, the two men returned and again asked about Plan C. This time Giesick was particularly interested in an additional rider of $100,000 that could be added to that plan to bring its total value to $300,000. On his earlier visit he had left the definite impression that the coverage was for him; now he said it was for his wife. He returned the following afternoon with her and asked specifically for the $300,000 policy. When he learned that the $100,000 rider didn’t cover accidents involving private automobiles, he said he didn’t want it after all and bought the $200,000 coverage in his wife’s name with himself as beneficiary.

Dillmann, at the end of a week’s investigation, now had a choice. One option was to fly to San Antonio and question Corey about the marriage and his trips to the insurance counter. But Dillmann, like a halfback, favored end runs over plunges through the center of the line. Obviously Corey was, in some strange way, linked to Patricia’s death. But he still had nothing that linked Corey directly with the events in New Orleans. And he thought he was more likely to find that in New Orleans than in San Antonio.

Back in New Orleans he returned to the Ramada Inn on Chef Menteur. He talked to two desk clerks, the manager, a waitress in the restaurant, and a maid. They had all seen Corey with Giesick the morning after the accident and identified him from a photograph. According to their statements, Giesick had returned from the hospital about 10 a.m. that day. He was covered with blood and a little later gave his clothes to a clerk to send to the laundry. About 11 a.m. he entered the motel dining room with Corey, whom these witnesses, like the Tele-Trip personnel, all described as heavyset and very shabbily dressed. A few minutes later a priest from the hospital phoned to tell Giesick his wife had died. Giesick talked with the priest for several minutes and then left the motel with Corey.

Late in the afternoon one of the clerks went back to Giesick’s room to tell him his clothes wouldn’t be back from the cleaners until the next day. Corey was with Giesick in the room. The two of them were packing suitcases into a maroon car with a white roof. Giesick said he’d pick up his clothes later and asked if he could leave his Monte Carlo in the motel lot until he came back for his clothes. The clerk nodded but when she looked for the car the next day, it was gone.

Two days later, on Friday, January 18, Corey appeared at the Ramada Inn again and asked for Giesick’s clothing. The police had requested the motel staff to notify them if anyone should come by to pick up this cleaning. The manager stalled Corey by saying he’d have to wait a few minutes as the clothes weren’t back from the cleaners. Corey, suddenly very nervous, didn’t wait. He got back in his car and sped out of the parking lot so fast that his rear wheels spun up a sheet of gravel. He stopped in the parking lot of the motel next door where he talked to a man waiting in a late-model blue car. The two men then drove off toward town.

The last person Dillmann interviewed was a maid who had seen Corey when he came back for Giesick’s clothes. She said he was the same man she had seen walking across the street toward the Quality Inn next door the day before the accident. Dillmann walked straight next door and, from the motel register, discovered that Corey had checked in about 2 a.m. on January 15, about 24 hours before the accident. Not only had Corey been in New Orleans when Patricia was killed, but he also had been staying right next door.

The same night clerk who had checked Corey into the motel, a young student with the unfortunate name E. J. Swindler, had seen Corey the next night around two o’clock, only about fifteen minutes before the accident. Corey had come into the lobby asking for a place where he could buy aspirin. Swindler had no idea where to suggest at that late hour, but Corey came back about 25 minutes later to tell Swindler he’d managed to find an open doughnut shop down the highway where he’d made his purchase. Swindler said Corey was in a happy, expansive mood and seemed very pleased with himself.

Dillmann also noted that one of the calls Corey made from his room was to the residence of a Dr. Charles Guilliam at an address on Tuxford Drive in San Antonio. And, exploring one final nuance, Dillmann checked back with the Ramada Inn to see if they had rooms available on the night of January 15. They had. Even though Corey knew the bride and groom well enough to have married them, he stayed out of sight in an adjoining motel.

Whatever Dillmann may have suspected at this point, all he could prove was that they were both in New Orleans on the night of Patricia’s death. He had yet to talk with either Corey or Giesick to see how they would explain their actions; nor had he talked with this Dr. Guilliam to see where, if anywhere, he fit in. And he could not identify the murder weapon. Had it been Corey’s car or Giesick’s or Guilliam’s?—had he, by the way, been in New Orleans, too?—or had the weapon been some other car entirely?

A week later, Giesick was arrested in San Antonio on an old charge of passing worthless checks. That was enough for Dillmann to catch a plane in the hope of getting to San Antonio and interviewing Giesick before he got out of jail. And the way he’d gotten arrested was the first sign that, while Dillmann was trying to crack the case from the outside, the case might be cracking from the inside, too.

Giesick had contacted a San Antonio police detective with a story that he had spent the last two years keeping out of sight because his life was under constant threat from a criminal named Zent. Now, Giesick said, his wife had been killed in an accident down in New Orleans and the police from there might be making some inquiries about him. Would the detective tell New Orleans that Giesick had disappeared because he was a police informer in San Antonio? The request was so strange that the detective simply ran a computer check on Giesick, discovered the warrant, and arrested him. Dillmann wasn’t sure, either, what Giesick was trying to do except throw up a smoke screen to hide himself from inquiries out of New Orleans. And Dillmann didn’t get to ask Giesick what he was up to. By the time his plane landed in San Antonio, Giesick had been released on bond—posted by Sam Corey.

Dillmann had arrived in San Antonio early Sunday morning, February 17. Although thwarted in seeing Giesick, he asked Corey to come to the police station at 10 a.m. and took a formal statement from him. Much of what Corey said was untrue. He “emphatically and positively” denied knowing whether Patricia had worked in a massage parlor; he said he had seen Giesick only one time since his marriage and that was in Richardson; he claimed he had first heard of the accident when Patricia’s mother called him at his massage parlor in San Antonio on the morning of January 16 and that he talked with Giesick long distance later that day; he said he had not been in New Orleans for several months; and he said that, although he had just posted bond for Giesick, he didn’t know his address.

Then, having watched calmly while Corey lied to him at every turn, Dillmann drove out to the Tuxford Street address of Dr. James Guilliam. A woman in her middle twenties with long, straight blond hair came to the door, said she was Dr. Guilliam’s wife, and that he was out of town where he couldn’t be reached by phone. She claimed her husband was a consulting psychologist and a business associate of Giesick’s. The only contact he had with Sam Corey was an occasional visit to his parlor for a massage. No, she had no pictures of her husband to show Dillmann. She became very nervous and insisted that her husband answer any more questions personally. As Dillmann left the house, he noticed a small detail that led him closer to what he had already begun to suspect—that Guilliam and Giesick were the same person. Patricia’s neighbors in Richardson had told him that Giesick had given his wife a St. Bernard puppy. There were several St. Bernard puppies in the Guilliams’ yard.

That growing suspicion was confirmed later that evening. Sitting in his motel room, Dillmann got a call from a San Antonio police officer who had known Giesick for six years. Giesick had asked the officer not to tell the New Orleans police he was now using the name Guilliam. This was, Dillmann thought, an obvious attempt to continue the confusion that Giesick’s double identity had created during all the investigation. It also meant that Giesick was getting more and more worried about Dillmann finding him and was taking greater chances to try to prevent it. The San Antonio officer told Dillmann that Giesick was living on Tuxford Street with his wife Kathi, a woman with long, blond hair. She was the same woman Giesick had been married to for the six years the officer had known them. He didn’t think they had ever been divorced although Giesick now was asking him to say that they had been divorced for several years.

Dillmann went to the Bexar County Bureau of Vital Statistics and found that Giesick had married Katherine Kiser in September 1969. There was no record of their ever being divorced. He talked with several neighbors near the Tuxford Street house who, from the mug shot taken when Giesick was arrested, identified him as their neighbor Dr. Charles Guilliam. Dillmann tried again to interview the blond woman he now knew to be Kathi Giesick, but she wouldn’t talk at all without a lawyer.

That evening, February 18, after Dillmann had been working on the case for three weeks, he got to interview Giesick at last. It was Giesick, finally, who contacted Dillmann and, while he refused to come to police headquarters, agreed to meet at Sam Corey’s massage parlor. During the interview Giesick claimed he was working with retarded school children in Dallas and had degrees from universities in Brazil, Germany, and Mexico. None of this turned out to be true. Giesick also volunteered, and subsequent checking confirmed, that he had been married four times: once from 1966 to 1967, which ended in divorce; once in California, a marriage that was annulled after three days; once to Katherine in 1969; and then, bigamously, to Patricia. His version of the accident was essentially the same story he told New Orleans police: he and Patricia had gone out by the bayou to look at ducks and she raced into the street where she was hit by a speeding car. Then, he said, the evening after the hit-and-run he’d flown to Houston and on to Dallas. He didn’t mention seeing Sam Corey until the night of January 17 when he flew to San Antonio. Toward the end of the interview Giesick began acting extremely nervous, insisting that he had to catch a plane to Dallas and didn’t have time to talk any longer. Dillmann pressed on. If he’d flown from New Orleans, what happened to his car? Well, he’d flown back to get it and on the way had stopped at the Ramada Inn to pick up his clothes. And yet, Dillmann knew, it was Corey who had tried unsuccessfully to pick up Giesick’s clothes. Why had he listed himself as a widower on his marriage license? Giesick said he’d lied about that to Patricia and was simply keeping up the lie. After that Giesick insisted on leaving to catch his plane.

Dillmann himself then flew to Dallas, where he told police what he’d found, particularly the new information that Giesick was already married when he married Patricia. They had a justice of the peace issue a warrant for Giesick on charges of bigamy. On February 22 San Antonio police arrested him in front of his house on Tuxford as he tried to flee in his Monte Carlo. Dillmann had thought this car was possibly the one that killed Patricia, but a thorough examination by the police lab found nothing that could prove the car had hit anyone.

Although disappointed—after all the time he’d spent on the investigation, the best case he could make against Giesick was bigamy, not murder—Dillmann returned to New Orleans and tried, in the hope he could find additional evidence, to discover more about Giesick’s and Corey’s activities while they were in New Orleans. He learned that Giesick, far from losing all means of transportation when he took his Monte Carlo in for repairs, had immediately rented another Monte Carlo from Avis. In fact, Avis had come to the dealership to pick him up. At two o’clock that night, exactly 24 hours before the accident, Giesick and Corey appeared at the Avis rental desk at the New Orleans airport where Giesick exchanged his rented Monte Carlo for another one that was identical except for color. He gave no reason for wanting to exchange cars and the attendant, when he checked the returned car, found nothing wrong with it. Dillmann was now disappointed to learn that the second Monte Carlo was out of the state and he would be forced to wait for its return before inspecting it.

He conducted several more interviews. A guard at the hospital had seen Corey there shortly after the accident. The doctor who treated Patricia said she had tire marks on the left side of her head and left shoulder. If she had been hit running across the street, as Giesick had claimed, she would have been struck around her waist and hips and thrown clear rather than run over. And Dillmann found Ricky Mock, the first person on the scene. When he heard the loud mufflers on Mock’s car, Dillmann deduced that this was the car with loud mufflers Giesick had described as the hit-and-run car.

At this point he was stalled in his investigation until the Avis car turned up; but he managed to make some progress anyway with the unwitting help of Giesick and Corey. They were beginning to show more strain under the pressure of Dillmann’s dogged pursuit. Corey resorted to a private polygraph examiner he had once employed to screen girls who worked in his massage parlor. Apparently Corey thought he knew enough about polygraphs to be able to beat the test. Instead the test showed deception or guilt when Corey answered no to the questions “Do you know who killed Patricia Giesick?” and “Do you know who was driving the car that struck Patricia Giesick?” Corey then pleaded with the examiner not to let the New Orleans police know the full results of the tests.

The examiner, of course, was legally obligated not to conceal possible evidence, and when Dillmann learned of the test he flew back to San Antonio. The examiner said he had concluded from the test that Corey was involved in Patricia’s death or at least had knowledge that Giesick planned to take her life. Dillmann went straight to the Tokyo House where he told Corey that, because of his knowledge of Giesick’s plans, he should voluntarily come to New Orleans and give a statement to police. Corey denied having any knowledge, but Dillmann told him what he’d just learned from the polygraph examiner. Flushed and nervous, Corey called the examiner, who confirmed that Dillmann was telling the truth. Corey then became mysteriously ill, complaining of severe pains in his chest. He said he would think about coming to New Orleans and tell Dillmann his decision the next day. But when Dillmann returned to the Tokyo House, the receptionist said Mr. Corey had suffered a stroke. Further questions were referred to Corey’s lawyer, William Miller. Dillmann had no luck that day trying to contact Miller.

Unless Corey agreed to go voluntarily, Dillmann had no way of forcing him, so he returned to New Orleans himself and waited—waited for the Avis car to turn up, waited for something to break in San Antonio. Three weeks passed and nothing happened. But during that time Corey and Giesick were apparently feeling the heat of the investigation more and more. They must have met together in fear but not yet, judging from the plan that resulted, in mistrust. The first Sunday in May, Giesick met in a Denny’s with a San Antonio police detective and regaled him with a tale about the night of Patricia’s death. The detective called Dillmann who in turn called Giesick so he could repeat the story.

It was the wildest and most desperate story yet. Giesick said he was ready to surrender himself in New Orleans and plead guilty to conspiring to kill his wife. Giesick said Sam Corey wasn’t involved in this conspiracy, and, on the contrary, had been the one who prevented him from carrying out his plans. Giesick said he had met a “hippie” he knew only as Ronnie in Dallas. They had conspired to take Patricia to New Orleans where Giesick was supposed to beat her over the head with a rock and Ronnie would run over her with a truck to make her murder look like an accident. Corey learned of the conspiracy, came to New Orleans, and talked him out of it. Then he and Patricia went out walking by the bayou. He told her of his former plans. She became hysterical and ran into the street where, completely by accident, she was run over. Although he had planned to kill her, her death was purely coincidental. Giesick added that now he knew he was a habitual liar but was under psychiatric treatment and thought he was making progress. He was willing to confess to conspiracy now because he believed he was emotionally unable to serve the long prison sentence that would certainly follow a murder conviction. He repeated that Sam Corey was never involved in the conspiracy. Dillmann was somewhat less than greatly moved by Giesick’s tender emotional condition. He assumed since Giesick had been so careful to exclude Corey from guilt, that Giesick was making his confession because of pressure from Corey.

Two days later Giesick called Dillmann again. The pressure had finally produced a break between the conspirators. Giesick said there had been an attempt on his life by, he believed, Sam Corey. He wanted to know, if he came to New Orleans, confessed everything, and agreed to cooperate, would he be granted a lesser charge than murder. Dillmann consulted the district attorney’s office and called Giesick back to say his cooperation would be taken into account but if he came to New Orleans he would be arrested. Giesick declined to come. “I’d rather take my chances with Sam Corey,” he said. But the break was final. Two days later Giesick’s attorney was in the DA’s office trying to work a deal to get Giesick a reduced charge in return for testifying against Corey.

On May 13 the Avis car, the one Giesick had rented at the airport the night before the murder, arrived back in New Orleans. A thorough inspection revealed two nine-inch strands of human hair wrapped around and embedded in a spot of grease on a tie rod near the right front tire. Dillmann sent these hairs to the FBI Crime Lab. In order to obtain samples of Patricia’s hair to compare with those on the car, Dillmann went to New Jersey where she had been buried near her parents’ home, obtained a court order, and had her body exhumed. He took samples of her hair and sent them to the FBI. Hair, unlike fingerprints, does not have enough unique characteristics for one to say with certainty that it comes from a particular person. But there are some fifteen different traits by which hairs can be compared, among them color, texture, oil, type of scales, and various others. The hairs on the car, which had been crushed and ripped from the scalp as they would have been in an accident, matched Patricia’s hair in all fifteen characteristics. Dillmann had found the murder weapon.

On June 6, 1975, a year and a half after he began his investigation, Dillmann told an Orleans Parish grand jury what he’d learned of Patricia Albanowski Giesick’s death. After listening to four hours of testimony, they returned indictments against Jim Giesick and Sam Corey for murder in the second degree.

But the conduct of the trial changed many things. The maximum penalty in Louisiana for second-degree murder is life in prison. Sam Corey now awaits his execution on death row.

Ralph Whalen, the man who prosecuted Sam Corey, joined the Orleans Parish District Attorney’s staff in 1971, immediately after graduating from the Tulane law school. He didn’t seem like one of that school’s most promising graduates. Not especially enamored of study, he had finished in the middle of his class and took a job with the DA as much from default as from choice. He spent his first week observing the trials in progress. That Friday afternoon, riding a crowded rush-hour bus home, he began to cry. The spectacle of defendants and victims and police and tales of horrible crimes and men and women hauled off to jail had overwhelmed him. He wasn’t sure he was doing the right thing. Perhaps his deepest sympathies were opposed to the very office he was now serving. Hadn’t he seen people go to jail that very week for smoking marijuana, an act he wasn’t sure should be a crime at all?

The following Monday, however, he was given a handful of case files, a pat on the back, and the instructions that it was time for him to get in there and start prosecuting. The moment he stepped into a courtroom as a lawyer with a case to win, those tears became a relic of a past life. The courtroom battle intrigued and inspired him; he lost his doubts about whether the defendants he prosecuted deserved jail; and he became so skillful so quickly that by the time the Corey case came along—the most publicized criminal case in New Orleans since Clay Shaw—the newspapers were referring to Whalen as “the Whacker,” and he had decided that a prosecutor’s job was his life’s calling.

Whalen found himself matched against a lawyer whose reputation was as old and established as Whalen’s was new and promising. Irvin Dymond, the most famous criminal lawyer in New Orleans, the man who had defended Clay Shaw, had taken Corey’s case. While Whalen was short, trim, neatly dressed, and aggressive and intense in the courtroom, Dymond had a calmer style, slower, and, in appearance at least, not at all flamboyant. About 30 years older than Whalen, Dymond had not only the benefit of longer experience in the courts but also a marvelous deep voice and a talent for a sonorous and compelling oratory that is seldom found outside the South. William Miller, Corey’s San Antonio lawyer, also helped with his defense. He had, strangely enough, first been Giesick’s lawyer. When Giesick abandoned him for C. David Evans, a well-known San Antonio attorney and former state legislator, Corey went to Miller. Dymond’s responsibilities were to try the case while Miller’s were research and investigation, a separation of duties that did not prevent the two lawyers from publicly disagreeing about the progress and direction of the defense.

The prosecution’s case, despite all the evidence Dillmann had compiled, was weakened by the lack of witnesses to the crime. There had been two people, a man and a woman, in a car in the parking lot where Giesick had left his Monte Carlo. Officers at the scene questioned them and discovered that, though they were both married, they weren’t married to each other. Both the man and the woman denied seeing anything. They pleaded with the officers not to take their names and the officers acceded. The prosecution could establish only that Giesick was present at the scene, but not what he did there; it could establish Corey’s whereabouts before and immediately after the murder, but had no evidence that placed him precisely at the scene. The DA’s office had no doubts that these were the guilty men, but juries were unpredictable. They might not convict without some direct evidence or testimony about exactly what happened that night. The events on Michoud Boulevard remained a large spot of white canvas at the center of an otherwise convincing painting.

At the same time, Giesick’s attorneys had been trying to make a deal for a reduced sentence in return for their client’s testimony against Corey. Giesick could be the eyewitness the prosecution needed. David Evans, Giesick’s attorney, also added another bit of pressure. He said he would fight extradition from Texas every step of the way. It was unlikely that, in the end, the Texas courts would refuse to extradite Giesick, but such legal maneuvering would tie things up in Texas for at least a year, perhaps longer. Eventually, the DA, who had come to believe that Corey was the instigator and mastermind of the plot, agreed to let Giesick plead guilty to manslaughter. Giesick surrendered himself and agreed to testify against Corey.

The case finally came to trial on November 6, almost ten months after Patricia’s death. It had been scheduled once before, but Irvin Dymond, saying that he’d not had time to prepare his case properly, asked Whalen if he would agree to a continuance. Whalen agreed, but as the November 6 date approached, found that he was the one now not ready to go to trial. In the last ten months, important witnesses had moved or changed jobs and Whalen couldn’t find some of them. He asked Dymond if he would agree to another continuance, but Dymond, thinking he had Whalen on the ropes, refused and insisted on going to trial. When the trial opened and Giesick and Corey stood stonily ignoring one another before the bar, Whalen shocked everyone by announcing that he was dropping the charges of second-degree murder against Sam Corey. A moment later he added, “Your honor, it is the state’s position that a charge of first-degree murder more accurately reflects the crime and we intend to seek such an indictment.” Corey walked out of the courtroom a free man only to have Dillmann arrest him once again.

Whalen, forced into a corner, had spent some time consulting the law books. Louisiana had recently revised its laws concerning the death penalty to comply with Supreme Court decisions. The result was a special and specific category of crimes that were defined as first-degree murder. That offense carried a mandatory death penalty. Part of the statute stated that murder is in the first degree “when the offender has specific intent to commit murder and has received anything of value for committing the murder.” The Louisiana lawmakers probably had murder for hire in mind in writing that passage, but Whalen saw no reason why it couldn’t be applied to Corey’s case. Wasn’t the state contending that his motive was more than $300,000 in insurance money? Would not obtaining that money be receiving something “of value for committing the murder”? One day after the second-degree murder charge was dropped, the same grand jury again heard Dillmann’s testimony and returned a first-degree murder indictment against Sam Corey.

When the trial began late in April 1975, the prosecution began with the testimony of a pathologist who had performed the autopsy on Patricia. Then Whalen put Giesick on the stand to tell how he and Sam Corey had plotted murder.

Whalen had warned the jury in his opening statement that he had made a deal with Giesick whom he described as “a killer, a murderer . . . a man about as bad as they come.” Though this might have seemed at the time like undermining his own witness, it was Whalen’s attempt to lessen the effect of evidence the defense would surely introduce about Giesick’s character. He had been diagnosed by a psychiatrist as a pathological liar with a lifelong history of anti-social behavior. He had threatened the life of the father of one of his former wives.

He had been indicted for writing bad checks. He posed as a doctor of psychology. He had made much of his living for the past ten years by confidence games and insurance rip-offs, an occupation that had forced him to adopt a double identity. Under cross-examination by Dymond, he freely described a method he used to steal cars from airport parking lots. Everything he had, as he would also admit on the stand, he’d gotten by cheating someone. And the defense witnesses, the majority of them, were people called to discredit Giesick with testimony about actions he wouldn’t admit so readily. A masseuse said he had suggested murdering her husband for insurance money. Another masseuse, one who had bought Sam Corey’s parlor in Irving, said she’d hired Giesick as a psychologist to help two of her employees who were having emotional problems. Giesick treated them by prescribing frequent sexual intercourse with him. Later he propositioned the woman’s fourteen-year-old daughter. Other witnesses testified to similar behavior.

Still, for a person as thoroughly bad as he was shown to be, Giesick made a good witness. He has an easy-going, soft-spoken manner and a glib tongue that, treacherous as it is, can also be charming. He does not, on first impression, seem like a killer or even, when he tries hard, which he did on the stand, like a liar. And in the end the jury chose to believe him.

The tale Giesick told on the stand was not so much of violence, although it was violent, and certainly not one of cleverness, but one of remarkable coldness, callousness, and cynicism. Giesick, using the name Guilliam, had met Sam Corey when he came to the Tokyo House in San Antonio to sell him a credit card service that day I was winding up my story. After that they saw each other occasionally and twice happened to run into each other’s cars. (These accidents had all the earmarks of insurance frauds.) Around November 1973, while they were eating in a restaurant in San Antonio, Corey first brought up the possibility of Giesick marrying a girl and the two of them killing her for insurance money. Corey said he knew that Giesick was wanted for a bad check charge and threatened to turn him in unless he went along with the plan. Their conversation lasted about an hour and a half and at the end of that time Giesick had agreed to the idea.

He began frequenting massage parlors in San Antonio and Dallas looking for a girl. Before long he found Patricia and married her. She was the perfect victim. She was lonely, gullible, down on her luck, and desperate for both money and affection. He began insuring her. On at least one occasion Corey provided the money for the premium.

After the marriage, Giesick drove with Patricia to New Orleans and checked into the Ramada Inn on Chef Menteur. He immediately took his car to the shop for unneeded repairs and from there called his wife Kathi in San Antonio who told him where Corey was staying. Giesick rented a Monte Carlo from Avis and met Corey at his Holiday Inn. Then Giesick drove back to the parking lot at the intersection of Chef Menteur and Michoud where he parked his rented car. He walked the rest of the way back to the motel. The plan was to make Patricia think they had no car. This would confine her to the motel most of the time and force her to walk across the highway to the small bar and restaurant if she wanted to eat. They originally thought this might provide an occasion for her to have an “accident.”

That night Giesick took the St. Bernard puppy out for a walk as an excuse to meet Corey. Corey signaled from his car by flashing his lights. They discussed possible locations and the mechanics of the crime. Then Giesick went back in, got Patricia, and walked her up and down Chef Menteur. Corey was on the road driving a Buick he and Giesick had stolen from Love Field in Dallas. But the traffic was too heavy to risk anything then.

Giesick took Patricia back to their room, took the dog out for another walk, and met with Corey again. They decided to try again that night on Michoud Boulevard near the bridge over the bayou. Giesick went back to the room and talked Patricia into coming outside with him once again. As they walked up Michoud toward the bridge, Giesick noticed a police car by his parked rental car. An officer was shining a flashlight inside. Giesick panicked a little, took Patricia back to their room, told her he needed time to think by himself, and, outside, told Corey the police had spotted his car. They both got in the rental car, Corey driving, and went to the airport where they exchanged that car for another one using the phony excuse about transmission trouble. On the way back, Corey checked out of his motel and moved to the Quality Inn next door to the Ramada Inn where Giesick and Patricia were staying,

The following afternoon Giesick picked up his car at the dealership and spent the rest of the afternoon and evening driving Patricia around and watching television in their room. (Patricia, however, later that night told her mother and a desk clerk that their car was still in the garage. The defense never questioned Giesick about this discrepancy.) Giesick took the dog out several times that night and met with Corey. Corey whispered through the door of his motel room, and Giesick stood facing away from him so Patricia, if she should happen to wander outside, wouldn’t see him talking with anyone. They agreed on a time and place.

After midnight Giesick drove Patricia to Michoud Boulevard. (Here again his testimony conflicts with Patricia’s comments about their car.) They walked across the short bridge and down to the edge of the bayou. Corey drove past, made a U-turn, and parked in front of the first house in the block after the bridge. He signaled with his parking lights that he was ready.

Giesick and Patricia walked up to the road. He stopped by a small tree. Holding his flashlight behind his back, he signaled three times. Corey signaled with his lights and then started toward them. Giesick waited for the right moment, grabbed Patricia, and shoved her and tripped her at the same time. Corey ran her down and kept on going. Sometime later, after the police and ambulance had arrived, Corey drove by the scene again. Giesick concluded his testimony by saying that he met Sam Corey on the roof of the hospital as Patricia lay unconscious below. “Don’t worry about it,” Corey said. “She’s not going to live. Everything’s fine. We’re home free.”

The rest of the prosecution’s case was designed either to augment or corroborate Giesick’s testimony. Whalen knew that Giesick’s psychiatrist would testify for the defense that the prosecution’s star witness was a pathological liar. But Whalen, by taking special courses and with a certain amount of study on his own, had learned rudiments of psychiatric theory and practice and how they applied to the law. He knew that the psychiatrist would also admit, as he later did during Whalen’s cross-examination, that the testimony of a pathological liar could be believed if it was corroborated.