This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Big Jim sits astride his Harley, waiting for a red light to change. It’s long after midnight and there’s not a car in sight, but Jim doesn’t think about running the light. A cop car could be sitting in the darkness around the corner, its cruising lights turned off. And now is no time for a Bandido to be getting into even minor trouble in Fort Worth. Ever since that fight at Trader’s Village and the arrests that followed, the cops have been chasing down Bandidos on any charge at all, even for minor traffic infractions. Now not only the cops, but someone else—nobody knows who—has joined the game. At midnight three weeks ago, chapter president Johnny Ray Lightsey was blasted with a .38, and he fell dead in the street. Jim blinks a little, remembering that Johnny Ray was gunned down while waiting at a lonely intersection for a red light to change. He knows it could happen again.

Part of the trouble with police is a Bandido tradition. Ever since the club’s first chapter was formed fifteen years ago in Houston, police and Bandidos have been instinctive enemies. The Texas Organized Crime Prevention Council has called the Bandidos a little Mafia, and with encouragement like that, Jim tells himself, it’s no wonder that every two-bit police recruit in the state thinks that he has to earn his uniform by harassing Bandits. The club’s founding president, Don Chambers, is locked up in Huntsville for a life term on a murder charge, and Jim believes Chambers is not the only Bandit wrongly in prison. “Free Don Chambers,” say white letters on the front of Jim’s black T-shirt. “Support Your Local Bandidos—Or Else,” they say on the back.

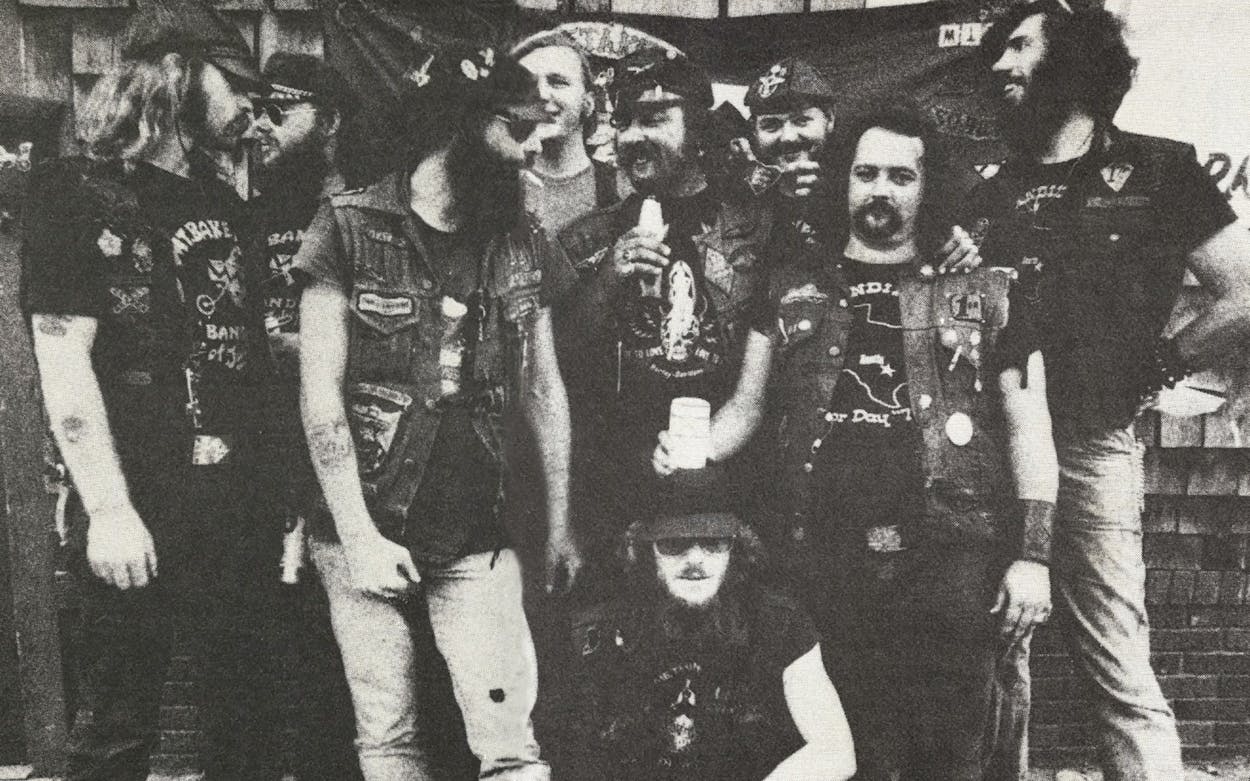

Run-ins with the police have not limited the growth of the Bandidos; if anything, their legal troubles have made them more attractive to their potential members. Leaders won’t divulge the group’s size, but today there are Bandido chapters in seven states, and probably 1500 members or more—enough to warrant the claim that the Bandidos are the nation’s second-largest outlaw biker clan, after California’s Hell’s Angels. Before joining up, most would-be Bandidos tell themselves, as Jim did, that being a Bandido means risking arrest and imprisonment every day. Rather than pale before that prospect, those Bandidos who stay in learn to welcome it, because if there are any qualities the macho motorcyclists respect, fearlessness tops the list, way ahead of honesty, intelligence, dexterity with a pistol, or even brotherliness.

“Doe follows Jim out to this bike, but she doesn’t move to mount it as usual. ‘Jim. I don’t want to be no Bandido’s old lady. You could get blown away. A woman can’t live with that, thinking her man may die any minute.’ ”

Jim joined the Bandidos four months ago, just when a new wave of police harassment was unfolding in the wake of arrests at the Trader’s Village chili cookoff in Grand Prairie. As both the police and the Bandidos reconstruct it, a young Dallas woman took leave of her boyfriend to beg a ride on a Bandido motorcycle. Half an hour later, when she and the Bandido rode back to the cookoff, the young lady leaped from the bike and screamed to her boyfriend that she had been raped. A free-for-all between bikers and onlookers ensued. The Bandidos joined forces and “all came together like a kind of magnet” one witness observed. At the end of the brawl, seven cookoff patrons were hospitalized, some for stab wounds. The Bandidos got off physically unscathed, but eight of them were jailed on charges ranging from rape to misdemeanor assault. As the Bandidos tell it, there had been no rape, and the member who gave the young lady a ride was Herbert Brown, not Ronald Kim Tobin, whom police charged with the crime.

The incident was a classic case of confrontation between outlaw bikers and the citizenry, and the highly publicized charges that came out of it gave the police a reason to come down on the Bandidos, whenever and wherever they could. It became almost impossible for a Bandido to cross town without being stopped for a flickering taillight or having to show title to his Harley. Club members in Fort Worth pooled their resources—and even took jobs—to bail members out of jail or to pay off bondsmen who held Bandido bikes as collateral. Jim, who had been in and out of outlaw biker groups for most of his adult life, had never seen teamwork and defiance like the Bandidos showed after the Trader’s Village bust. So he joined up with them, damn the police.

“Damn the cops, anyway,” Jim thinks to himself, chuckling a little. He’d had trouble with them virtually all his life. His mother, lacking anyone else to call for help, telephoned the police when her labor pains began. A patrol car came for her, but before it reached the hospital, Jim was born, right there in the back seat. The first event in his life had not been the caress of his mother, but a butt-beating by a cop, and life had followed that pattern pretty closely ever since. If there was anything Jim aspired to in his good-natured moments, it was getting a chance to give some cop a good butt-beating, just to even the score. As a Bandit, he might sooner or later get the chance.

The front wheel and the headlight of Jim’s Harley flutter up and down, vibrating unnaturally. The vibration comes from underneath him, from the motorcycle’s frame, which is broken in three places—two of the breaks are at the back, where the engine joins the transmission. When the light changes, Jim eases out, hoping to keep the vibration down. He can hear his motor squirming around as he gains speed. If he doesn’t weld those breaks in the frame, it won’t be long before the engine twists loose from its mounts. He promises himself to do something about it soon.

Every night at this hour for the past ten days, Jim has ridden this road over to the Nevada Club,* a topless bar on the East Side, to pick up Doe at closing time. He never asked her to move in—that would have been too much trouble—but she had anyway, thinking herself privileged to be able to. The money she brought in from her dancing job wasn’t half bad, he knew, but that wasn’t all Doe had going for her. Unlike the other women he’d known, Doe wasn’t a troublesome bitch, always giving orders or complaining. If she keeps behaving right, Jim tells himself, she might be worth making into a permanent old lady. He hadn’t given her a Bandido jacket patch for old ladies, but he might, in about another month. Another month would give him time to see her react to trouble. Within a month, there would probably be a big bust, or somebody else would get shot. An incident like that would give Jim the opportunity to see if Doe was worth being made a Bandido old lady, because it would put her through the test of Bandido bad times.

The vibration in his engine quiets as Jim speeds on the final stretch going out to the Nevada, but it comes back as he slows down to enter the sandy parking lot. He parks his bike and goes through the small throng of hangers-on gathered around the front door. Everyone but employees has cleared out of the club. Inside, Doe is sitting with Julie, also a dancer at the club, and the girl who had introduced Jim to her. Julie liked to consider herself Jim’s old lady, but he had never taken her in.

Doe follows Big Jim out to his bike, but she doesn’t move to mount it as usual. Jim looks up. She raises a pale hand to her mouth and yells out over the din, “Jim, I’ve got to talk to you.” He pushes the kill switch and his motor goes dead.

Doe, a frail young woman of about twenty, runs her hand through the black, almost kinky hair that clings close to her head. Jim looks down at her waist, where the ends of her blouse are tied, about three inches above the belt buckle on her jeans. He stares up at her cleavage, where the butterfly tattoo is. Around her neck is the same little bare silver chain she always wears. In all important aspects, she looks the same to him. Jim wonders what she could want.

“So, yeah, you want to talk to me?” he mumbles.

“Jim, I don’t want to go home with you tonight. I don’t want to be your old lady.”

Jim strokes down on his shaggy beard and spreads his legs out stiffly, one on each side of the Harley. The skin on his broad face is drawn tight now, and he stares at Doe over the handlebars, nailing her with his pale blue eyes.

“Yeah, why not?” he growls after a minute.

As she explains, he shrugs his shoulders, and, with his left hand, takes off his Harley cap, running a palm over his thinning hair.

“Jim, I’ve been kidding myself. I can’t be a biker’s old lady anymore. I’ve tried before, and it just won’t work. I need a man who works forty hours a week, just like me; not somebody who’s going to spend all day puttin’ around with his buddies.”

Jim has heard these gripes before but never paid them any mind. He’s hacked now that she would take them so seriously.

“Lookit, I’ve already heard it, right? What are you going to do, tell me about your first old man again?”

“Well, Jim, it’s for real. My old man was as much a one-percenter as you are, and you know it. Then that truck hit him and—poof—he was gone. I’m not ready for that again. I can’t handle it. And here you are, a Bandido. You could get blown away anytime, and you know it. A woman can’t live with that, thinking her man may die just any minute.”

“If you talk like that, you ain’t ready to be a Bandit’s old lady,” Jim drawls, smiling ironically.

“That’s right. I don’t want to be no Bandido’s old lady.”

“Well, that’s it, I guess,” Jim mutters. As she stands there a little distraught and unsure of herself, Jim fires up his motor. He could hang around and argue with her, maybe even change her mind, but he doesn’t see much point in it. That would be conduct unbecoming to a Bandido. Without another word, he rolls his machine back away from the sidewalk and roars off.

He heads his bike to the north side of town, toward Nasty’s house, where he knows his Bandido brothers will be tinkering with their motors in the garage. But the incident with Doe has disturbed him more than he would like to admit. He has known and lived with several females, but none like Doe. For one thing, she is headstrong, and, reluctantly, he admired that in her, even as she was telling him off. Not many women, he thought, had the nerve to come straight out and rebuff him like that, right on the street. The others would have run off, leaving notes behind or telling him good-bye over the phone. But not Doe. She was ferocious, despite her size.

Nasty’s garage is a center for the Bandidos and has been for about six months, ever since the police raided their last clubhouse after the Trader’s Village arrests. Nasty’s two bikes are usually parked inside amid the refuse of another half-dozen bikes and parts from perhaps twenty more. Around its pine walls are several mechanic’s tables, and on its greasy floor a scattering of tools. Centerfolds from Easyriders, a biker magazine, and photos of two or three of the looser women who hang around with members of the Fort Worth chapter are nailed to the walls.

The windows in Nasty’s simple frame house are dark when Jim rides up, a sign that Nasty’s wife and son are in bed. As he rounds the corner, headed for the garage in back, the garage lights go out, and the four Bandidos inside, on guard against the sound of any bike—for it might carry Lightsey’s killer—come creeping out the doors, taking cover with their weapons. But they recognize Jim and, with a round of laughter, go back into the garage. When they switch the lights on, Nasty and E. J. are over by the red refrigerator drinking beer. Both have just come in with the night’s receipts from the Magic Lounge, a bar on the Jacksboro Highway that Nasty operates. Jim gets off his bike and saunters up to the refrigerator to take out a beer.

Though Jim has grown accustomed to him, Nasty is a terror to behold. He is a satanic reincarnation of Abe Lincoln. Dark eyes peer out from his narrow face, which is surrounded by a thin, straight, glistening black beard. Like the Great Emancipator, he speaks in a high-pitched, gentle voice that contrasts with his lankiness and his dead-serious demeanor. On one wrist he wears a studded leather band. From his hip pocket sticks the narrow, heavy handle of a 9mm automatic pistol, and above his bed, Jim knows, hangs a Thompson semiautomatic. Seeing Nasty loitering in the garage or behind the bar at the Magic Lounge, there is little to show that the man is a father, a homeowner, a decorated veteran, and the husband of an entirely traditional wife whose occupation is nursing.

E. J., the short, squat figure next to Nasty, is Jim’s oldest friend. He is wearing a black Bandido T-shirt, his tattooed arms are akimbo, and he has a beer in one pudgy fist. E. J. seems to balance, not stand, on tiny feet shod in blue and yellow jogging shoes rather than black motorcycle boots. Wiry black hair sprouts wildly from the top of his head, and his unshaven chin. His paunch overhangs his jeans all around the waistband.

E. J. and Jim had ridden together even before both became Bandidos. Once, when Jim’s bike was down, he borrowed a car from E. J. and drunkenly drove it through the plate-glass window of an orthopedic supply house, which brought suit against them both. It was Jim who was riding with E. J. the night that E. J. plowed his Harley into the front seat of a Toyota as it made a left turn. The Toyota simply collapsed, and its driver was killed by the impact. E. J. was thrown over the car’s roof and suffered two broken legs. Someone remarked that the Toyota looked as if it had been hit by an unidentified flying object, and ever since then, E. J. had been nicknamed UFO. “That means Unidentified Fat Object,” he sometimes jokes when introducing himself. E. J.’s strongest asset was his sense of humor, and Jim knew it well, because when Jim didn’t have an apartment of his own—and that was most of the time—he lived with E. J. and his old lady, Trisha, a dancer at the Magic Lounge.

The two other Bandidos in the garage are Rockin’ John and the club’s pledge, Ken, usually called by his title, Prospect. Rockin’ John spilled his bike on one of Fort Worth’s remaining brick streets last weekend; only today did he get out of the hospital, and the beer he is drinking doesn’t quell the pain that still plagues him. Rockin’ John is kneeling at his Harley, trying to wrest off the seat. Prospect is helping. Nobody notes that Jim is perturbed. After a few seconds, Rockin’ John, disgusted with a rusted bolt on his wrecked bike, bellows out an obscenity.

Jim chuckles. “You think you’ve got troubles. Well, brother, I just lost my old lady.”

“So what’s that?” Rockin’ John spits back. For Bandidos, bikes are more important than women.

Jim doesn’t know how to reply at first. Then he blurts out, “Well, if nothing else, that’s going to be a helluva blow to my income.”

Everybody laughs, especially E. J., whose roar can be heard halfway down the block. When the garage has quieted down again, Rockin’ John continues needling Jim.

“Man, I can see you could sure use some of that income. Look there at your pants,” he says, pointing at Jim’s crotch.

Jim, who has sat down on a wire milk carton, casts his eyes down to his legs. His faded denims are ripped at the seam on the left side. He is not worried by that, because he has another pair in his room at E. J.’s place. But somehow this problem with Doe has not come to an end that he can live with.

“Don’t worry, bro, if she don’t come crawling back tomorrow, I’ll give you my old lady,” E. J. says, putting a pudgy arm around Jim’s neck.

“Say, now, don’t do me no favors,” Jim drawls.

“A knife pops up, its blade glinting in the light. The Chicano has the knife. Lloyd spins away and picks up a pool cue. Bandidos, itching for some action, form a cordon around the pool table, sealing off the area of conflict.”

About noon, E. J. stumbles into Jim’s room in the house they share, grabs Jim by the shoulders, and shakes him.

“Say, bro, wake up. It’s Doe on the phone. Says she wants you back.”

Jim blinks. “Huh? Doe? Shit!”

“Do what you want, bro. I’m just giving you the message,” E. J. growls, trundling back off to his and Trisha’s room.

Still in the ripped pants he wore last night, but shirtless and barefoot, Jim rises and makes his way to the wall telephone in the kitchen.

“This is Big Jim. Who is it?”

“Jim, I have to tell you that I screwed up last night.”

“Huh! Yeah, you can say that again.”

“I’m serious, Jim. I still want to be your old lady.”

“Well, you’re going to have to earn it now. Things won’t be the same.” He grins, awaiting her response.

“Jim, I mean it. I’m sorry. I want you to come get me so we can talk.”

“Well, I ain’t got much to say.”

“Jim, I’m serious. Come get me now. I’m at the Nevada.”

“You hold on there. It’s going to take me a while, you know. I just got up,” Jim explains. He holds the yellow receiver at arm’s length and blinks at it. Little noises are still coming out; Doe is talking. He blinks again, and hangs the receiver in its cradle.

He tells himself that it was probably some guy. Some jerk came to the club and Doe wanted to hop in bed with him. That’s why she dreamed up that whole rap about not wanting to be a Bandido’s old lady. But there’s no sense in bringing up anything about another guy, he decides. After all, he is back in command.

He brushes his teeth, finds his boots, shirt, and Harley cap. In the kitchen he makes a cup of coffee, and sits at the table, groggily mulling things over. There’s really no sense in going over to see her. He could just pick her up tonight at closing time as usual. But he decides to go over to the Nevada anyway.

Fort Worth in autumn is a nearly ideal town for biking. The winds are not high and the cold has not bitten hard yet. The streets are wide and traffic is relatively thin. With practiced ease, Jim cuts in and out, passing cars that are already exceeding the speed limit. Only one stoplight halts him en route to the east-west freeway.

The freeway was resurfaced last spring, and the new finish is not good for motorcycles. Grooves half an inch deep snake along the pavement, to reduce hydroplaning on rainy days, the highway department claims. But the new surface steals traction from narrow motorcycle tires. The treads of Jim’s front tire catch in the grooves, causing the wheel to bob and bounce. Jim feels the traction slip, but he has learned how to deal with it. The higher the speed, the less noticeable the loss of traction. He races down the freeway at 80 mph, not because he wants to see Doe, he tells himself, but because he doesn’t want his bike to spill on the pavement. In minutes, he is at the exit nearest the Nevada.

Doe is waiting for him outside. He rides up next to her, and she mounts the bike without saying a word. Pressing her hands hard against his waist, she leans forward, and with her lips next to his ear, speaks over the hum of the Harley’s engine.

“Honey, let’s get some lunch.”

Jim nods.

They ride back to the north end of town, to a favorite Bandido diner, where both of them order without saying anything to one another. Jim is waiting for her to speak first, but Doe says nothing. When they have finished eating, she pays the tab and they walk out. Jim starts his Harley up and she climbs on back.

“Coming to get me tonight?” she asks as they pull out.

Jim doesn’t answer. When they pull up at the Nevada a few minutes later, she asks again, as if Jim hadn’t heard the first time.

“Well, I think it would be better if you met me at Kim’s house,” he mumbles.

“If that’s the way you want it,” she drawls, as slowly as she can. Jim turns his Harley and rides off without nodding her way.

Nine figures kneel in a circle in the shadows of dusk on a parking lot behind a beer joint on Fort Worth’s South Side. Each Friday evening the Bandidos come here for their weekly meeting. The owner of the stark tavern was an admirer of Johnny Ray Lightsey, and he still welcomes the Bandidos; if nothing else, they buy a few beers before and after their powwows. Now that Lightsey is gone, the chairman of the meetings is Kim Tobin, 28, a husky six-footer who works weekdays as a diesel mechanic. His long blond hair is pulled back into a ponytail. He listens more than he speaks, and when he does speak, it is in the manner of a still-shy adult. The chief business tonight is filling a vacancy for vice president. There is no show of hands to make it formal, but Tobin, voicing the consensus, tells E. J. he’s it. Elated, E. J. challenges everyone to a game of pool back in the bar, where Prospect, several women, and a couple of Bandidos from out of town are waiting.

In the group of well-wishers is a gargantuan, swarthy young man with a beard stubble and bushy black hair. His filmy pink shirt is unbuttoned above the waist, and there are two chains around his neck, a bear claw hanging from one, a five-pointed silver star on the other. This kid, Lloyd Tobin, is Kim’s nephew. The Bandidos protect him, perhaps because he is unable to fend and befriend for himself, even when sober. Tonight he is staggering drunk. He wanders from the sidewalk out front to the bar and pool tables inside, giving everyone strong-arm embraces they could do without. Apparently penniless, he guzzles the drinks others offer him.

Jim circles through the crowd. There’s no sense saying so, but he’s a little ticked by the incident with Doe last night. She’s got no right to tell him to work, Jim thinks. Besides, she’s not the only woman he can have; there are others. One of them is Nadine, a barmaid at the Acapulco Club. Jim hasn’t seen her in several weeks, because he hasn’t wanted to. If he shows up tonight, he reasons, she’ll probably be so overwhelmed that he can wheedle free beers from her for the whole Bandido club. He proposes to Kim that they ride over to the Acapulco, and when Kim nods okay, everyone prepares to go.

There are a dozen black Harleys outside, all of them belonging to Bandidos. One by one, the riders crank them up. Kim leads out across the street, and the others fall in behind. Nasty brings up the rear, fishtailing for fun every time they stop at a light. The Bandidos are masters at riding in packs, handlebar to handlebar. When their line rides up on motorists, the cars slow down to let them pass. The Bandidos whip through traffic at more than 50 mph, while Lloyd weaves drunkenly in his Chevy, following about twenty yards behind. A cop comes in sight and, bypassing Lloyd’s swerving vehicle, tails the Bandidos, five yards off Nasty’s taillight. The Bandidos slow to 35 and creep onto the parking lot of the Acapulco, as the cop rolls slowly by, peering as if trying to pick out a particular member. The Bandidos pretend not to see him and file inside.

The Acapulco is a neighborhood club that on weekends attracts single females as well as men, most of them Mexican American. There is a small dance floor in one corner and pool tables against another wall. The sleek U-shaped bar is heavily populated tonight.

Most of the Latinos sport shiny print shirts open at the chest, wedge heels, and Sansabelt pants, and at least half of the young gallos wear gold medallions around their necks. When the Bandidos come in, the Acapulco’s male patrons frown a bit, staring at them from corners of the room and the other side of the bar. Several look up from the pool tables, mystified as much as irritated. The women move a little closer to their dates, seeking shelter; those without men turn their heads away. The Bandidos are now in a situation biker patois describes as “being ugly in a no-ugly zone.”

Suddenly, there is a commotion over by the pool tables. Everyone, Chicano and Bandido, rises to look. Lloyd is scuffling with one of the Latinos, a young man with a neatly-trimmed black goatee. A knife pops up, its blade glinting beneath the Tiffany-style lamp that lights the billiard table. The Chicano now has the knife, having wrested it from Lloyd’s fist. Flustered, Lloyd spins away and picks up a pool cue. Then he advances on the goateed Latin with his head lowered, like a swordsman stalking his opponent.

Kim strides in through the back door, the entrance nearest the pool table. He steps between Lloyd and the Latin, lays a hand on Lloyd’s cue, and with an authoritative flick of the arm shoves his nephew backward. Bandidos spring out of other nooks of the bar, grab Lloyd, and drag him out the back door; Lloyd shouts as he goes. The Bandidos form a cordon around the pool table, sealing off the area of conflict. Some stand with legs spread wide, their hands twisting pool cues held waist high. Everyone is waiting for an order from Kim.

The Latins congregate on the other side of the room, spouting Spanish. Some of them glare over at the Bandidos, but others are merely watching curiously, “¿Mano, qué pasará next?”

A second Latin has somehow wedged himself in at the pool table, a man older than the goateed youth who took Lloyd’s knife away. The older one holds the other by the shoulder. Tobin is talking to them, but the music is too loud; no one else can hear. He is not apologizing, it seems; his gray eyes are intent on the two men confronting him.

The goateed Latin stomps away from the pool table over to the bar, where two male friends and a woman gather around him, telling him to cool down. Instead, he breaks away for an instant and, pointing at the Bandido line, screams, “They’re just a bunch of pussies. Pussies—that’s all they are!” His friends pull him back to the bar, but the Bandidos, stung, tense up on their pool cues, itching for action. Tobin, however, gives no signal to move. The older man, apparently an uncle of the goateed youth, is now nodding his head in agreement with something Tobin says. Tobin sits down on the edge of the pool table and, calling Prospect over, orders him to bring a beer. Then he lays aside his cue, and looks at his hands as he chats with the older man. He pulls from time to time on the brim of his black Gimme Cap. When Prospect brings him the beer, he fondles it as he speaks. The dispute isn’t resolved yet, but the Bandidos can see that Kim won’t be calling them to combat. The Latins drift apart, and most of the Bandidos slink outdoors, where their bikes are. Tobin and the older man are left alone, conversing at the pool table.

Ten minutes later, Tobin comes out of the bar. He wants no part of their banter. Instead, he picks Lloyd out of the circle and upbraids him. “Now, listen up, Lloyd, I know you got riled, but you had no right to. You’ve got to think about these things more. You know you’ve already been to the joint once, but you’re about to get us all into trouble for you. Listen, you’re not alone anymore. You’ve got us; you’ve got a family now. We’ll take care of you, but you’ve got to understand that now you have more people to think about than just yourself.” Lloyd, who is mute throughout the little lecture, is overwhelmed and blubbering by the time Kim finishes. He throws his arms around Kim, who returns the embrace. Pretty soon, the other Bandidos pass by, patting Lloyd on the back. When he raises his bushy head and asks who has a cigarette, everyone knows he has regained composure. The trouble with Lloyd, everyone agrees, is that he’s not Bandido material. He should know that with Lightsey’s killer running loose, Bandidos must guard their violent urges. “We’ve got to save ourselves for the shithead that shot Big Johnny,” one of them tells Lloyd.

Bandido Weird Larry is sitting on his haunches over by the bikes when Big Jim steps out of the club with Nadine, the barmaid. Larry rises to his feet to join the crowd around her. Though married for more than fifteen years, Larry has been quarreling with his wife ever since he joined the Bandidos four years ago. This afternoon they were spatting again—over his paycheck from the fencing company he works for—and tonight Larry is looking for a diversion from his troubles at home.

A fair-skinned girl with shoulder-length auburn hair, Nadine can’t be a day older than eighteen. She is also either stoned or drunk. Big Jim dwarfs her, his arm around her neck. She scissors her legs nervously back and forth, answering the Bandidos’ jive questions, hugging closer to Jim when they laugh. Before long, Larry belts out the perennial biker demand: “Show Us Your Tits!” There is a general murmur of glee as she raises her cotton pullover and exposes an apple-colored nipple on a spotless white breast nearly as large as a football. “How about that!” Weird Larry exclaims as she puts an arm around him. Big Jim momentarily leaves her side, and she looks up at Larry from under his wing, asking, “Aren’t you one of my brothers, too?” Larry points to his Harley hat festooned with a dozen trinkets, then shows her the Bandit patch on the back of his denim jacket. Then he raises her blouse again, and she looks at him, and says, giggling, “Go ahead, lick it.” Larry bends over her, and another Bandit takes over the other breast.

“Say, Nadine, you’re going to ball us all, aren’t you?” Larry squeals out.

“Sure,” she stutters. “You’re all my brothers, aren’t you?” Somebody assents, and she assures them, “I’ll give y’all anything you want, ’cause you’re my brothers and I’m your sister.” There is drunken or drugged pride in her voice.

But Big Jim comes from the back of the circle to intervene.

“Listen, brother, this chick has got to go back inside right now. She’s got work to do.” Obediently, the girl turns to go, and as she walks off, Jim tells her to bring some beer. A few minutes later, she comes back with cans of Coors and Budweiser. There are cries for more beer, and she returns inside with Jim close at her heels. She goes behind the bar and gives him a beer. Then, a moment later, when the bartender and manager are not looking, she sets up another. The can is still unopened. Jim lowers it into a pocket of his black leather jacket. She passes him another and another. Five minutes later, Jim goes back to the street with half a dozen beers in his jacket. A few seconds behind him, the girl steals out, a beer under her blouse.

For the next hour, Nadine pivots back and forth, inside and out, as if the club gave curb service to Bandidos. When closing time comes, she steps out with Big Jim at one side, Larry at the other.

Everyone mounts and rides to Tobin’s house, a sparsely furnished shack on the North Side. An out-of-town Bandido and two locals crowd around the rear door of a van, preparing its bed for the gang bang. Doe, still in the clothes she wore this morning and looking aged with fatigue, and Julie, outfitted in cowgirl garb, pull up in Julie’s pickup. Both have just gotten off from their stage jobs at the Nevada. Instinctively, they know what is afoot. Doe makes straightway for the living room, where Nadine stands under the arms of Big Jim and Larry. She, or someone else, has removed her blouse. Doe stops just inside the doorway, listening.

Larry and Jim are arguing like farmers disputing ownership of a cow.

“Jim, there ain’t no way this girl can be your old lady.”

“Huh, where’d you come from with this shit?” Jim asks Larry, blinking puzzledly.

“If she’s your old lady, have you got a patch on her?”

“I ain’t got to,” Jim slurs, a little drunkenly. He has not turned to see Doe standing behind him.

“What do you mean you ain’t got to have a patch on her? Ain’t you never heard of an old lady patch?”

“Man, I got three old ladies now, and they only give you one patch. On top of that, brother, I ain’t given an old lady patch to none of my old ladies.”

“That’s just the point, see. You got to have a patch on your old lady. One patch, one old lady. You got to have a patch on all your property.”

“What do you mean, I’ve got to have a patch on all my property. I ain’t got no patch on my pocketknife, and it’s mine.”

“Yeah, but you got to have a patch for an old lady.”

“Look, Larry, the girl is with me and you can’t claim her. She’s going to be my old lady, not yours, and that’s it, brother.”

Only a few minutes earlier, Jim planned to give Nadine to the club for a gang bang. But Larry’s insistence, his off-the-wall lecturing, has gotten on Jim’s nerves. Now he claims Nadine as an old lady and is convinced he always planned to. Nadine, however, has run off in the confusion—Doe and Julie have handed her a blouse and hustled her off to the back of the pickup where all three are talking low. Jim doesn’t know where Nadine has gone, but he fears that if the argument with Larry continues, he and a brother Bandido will come to blows. He wheels and goes outside.

On a sheet of notebook paper, Big Jim’s first two old ladies are writing out a set of rules for the new recruit, who has enthusiastically grasped the prospect of old ladyhood. As Doe writes, Julie explains to Nadine what each rule means. The rules, which have apparently never been written out before—the men in the yard laugh when they are told what the project is—are common sense to Bandidos. They say that old ladies must help keep their men and motorcycles in good order, contributing to the financial needs of both. They forbid a Bandido’s old lady to gossip about club members when women gather together, and they command above all obedience, cleanliness, and truthfulness. There is a prohibition against unauthorized adultery, though it isn’t called that.

By now, everyone knows that there isn’t going to be any turn-out. Some club members, like E. J., have already gone off with their own old ladies, and others, like Nasty, who did not bring their wives, have gone home. Even Larry has left for his house. Jim, nearly alone now, walks gingerly over to the pickup. He steps quietly up to the back and puts a forearm on Doe’s neck. She cranes her neck to see him. “Yeah, what’s up now?”

“Let’s go home,” Jim mumbles.

Doe looks at him, then turns her head back to Julie and Nadine, who have heard, and are staring at Jim, waiting for him to beckon. But Jim says nothing more.

“What about your other old ladies?” Doe demands sharply.

“I ain’t got no other old ladies,” Jim mutters, glancing downward. Then he looks up at her again. “All I got is just one.”

Nadine only vaguely understands what is said, but Julie catches it.

“You goddamn scooter slime, you lousy damn scooter slime!” she wails.

Jim winces but turns away. Doe stands up in the pickup bed, then jumps over to follow behind him.

When Doe awakens the next morning, Jim is not in bed with her. The kitchen door is open, and Doe looks out. There sits Jim, on the back of his bike, legs outstretched, feet crossed on the gas tank, the chrome studs on the brim of his Harley hat gleaming in the September sun. Gingerly, and with the cheer that carried over from last night’s victory over the other women, she opens the screen door and calls out to him.

“Honey, do you want some coffee?”

Jim looks up from his musing.

“Naw, never mind.”

“Is there anything I can do for you?”

Jim chuckles, then looks down his legs to his feet again. “Now that I think of it, you might buy me a new bike.”

She giggles and steps out onto the porch, but Jim, raising a hand in the air, halts her before she can come to his side.

“Listen, baby, don’t bother me now. I’ve got some thinking to do.”

“What about?”

“Aw, about them Hondas. I can’t see why anybody wants to ride ’em,” he quips. The Bandidos’ antipathy toward Hondas is endemic. A real man can only ride a Harley.

Doe goes back inside without saying anything. Today is Sunday, a day off for her, and waiting in the house for Jim to think through some silliness—probably something about his bike—is not what she had planned for the day.

Jim looks up at the tree branches overhead, which have already lost their leaves. It’s nearly October. Winter will be coming and that will make his pickup a necessity. But the old Datsun, parked a few feet away in the back yard, won’t run anymore. It will take money to fix it. He’s a month behind on the payments for it, too. The finance company will be wanting money before long. What Doe brings in will help, but that alone is not enough to make it through the winter.

Winter isn’t the only problem, either. There’s self-defense. Jim doesn’t own a weapon; he borrows a pistol when he can from one Bandit or another, but most of the time he’s unarmed. Lightsey’s killer might come back, and Jim needs a gun—to greet him, he thinks, chuckling aloud.

Getting an income is a problem almost too big to think about. What Jim would like is to go into some kind of business. The trouble is, he doesn’t know what kind of business to start up. He’s never given business or money that much thought before, and now, because he has no money, he can’t go into business no matter how much he may want to. There’s no sense in thinking about that, he tells himself.

There are other options, of course. He could let Julie come in as his second old lady, like she wants to; that would give him the income of two dancing girls. But both of them would have to eat, too. And they’d probably be continually harping at him about something. It’s not worth it, Jim thinks. Women are too much trouble to manage. There’s running dope, or selling hot bikes, or burglary, but Jim decides against those pursuits, too. Jails are cold in winter, he recalls. Sooner or later, a man with dealings like that has to go to jail. Being a Bandido is jail risk enough.

But all that only leaves one thing: work. It’s hard to work for a boss, he reminds himself. But what else is there to do? He considers his assets. He has no skills, except being a Harley mechanic—and there’s no market for that. He has an equivalency diploma, an honorable discharge from the Navy, and a prison record for auto theft: not much to offer. He’d have to lie about most of his life to get a job. Nobody would trust him. He’d have to pretend he wasn’t a Bandit, and that prospect chills him. About sunset, he crawls down from his bike and goes indoors. He still doesn’t know what to do about an income. One thing is for sure, though. He’s not going to tell Doe about any plan to look for work. That would make the bitch think she’s running the show.

The next day, after taking Doe to the Nevada, Jim stops by the diesel shop where Kim works, hoping that Kim will have some advice. Kim has more than that. If Jim wants to come on as a mechanic’s helper, he says, there will be a job open next week, right there in the same diesel garage. Jim agrees to try it out.

Back at home, however, he sees new problems with working. For one thing, his bike won’t hold up long, and if he starts a job, he won’t have time to fix it. He will need the Harley to ride to work on, and that means he’ll need to be finished with the repairs by Monday. Jim starts in immediately. By nightfall, he has the Harley on a box and the wheels off and he’s ready to pull the engine.

The next day, Doe takes on her assigned role as parts cleaner, without knowing why Jim is impatient to rebuild the bike now. E. J. joins in, too, but as an equal.

“There’s two important skills you’ve gotta have for a job like this,” E. J. counsels. “You got to have the know-how and the know-where. You’ve got to know how to do the work, and you’d better know where to get the parts.”

They visit other bikers, even several who are not Bandidos. The parts come in, almost all of them from trades with other Harley riders. A few items, like piston rings, they buy from the dealership, though neither of them enjoys giving the dealer their trade. In their eyes, Harley dealers are little more than profiteering pirates. By Thursday afternoon they have reworked the motor inside and out and have also borrowed a welding rig for work on Friday. It is dark as they lay the engine aside—time for E. J. to take over the Magic Lounge from Nasty, who is getting off early that night. When E. J. gets in his car to leave, Jim jumps in with him.

Several Bandidos are already on hand at the lounge. Prospect, Herbie Brown, and Kim are there. About 11:30, Lloyd comes in and sits down with the Bandidos, who welcome him as they always do, with free beer.

About midnight, twenty blocks away, Nasty is awakened by the sounds of banging at both the front and rear doors of his house. Naked, he leaps from bed, picking up his automatic pistol and running toward the rear of the house. As he peeks out through a curtain, his kitchen door is thrown open by a cop.

“Get your family out of the house!” the patrolman bellows.

The garage, fifteen yards from the back door, is in flames. Nasty pulls on his jeans and ushers his wife and child out the front door. Still barefoot, he runs to the rear of the house and begins hosing it down; paint on the wooden structure is already blistering under the heat.

After the fire crew has come and gone, he gets a flashlight and tallies up the ashen, soggy remains inside. Two bikes and hundreds of parts are ruined. A padlock from the rear door of the garage is missing and so is a set of Harley gas tanks. Somebody has broken into the garage, taken what he wanted, and set it on fire.

The Bandidos at the Magic Lounge do not hear about the arson until much later that night. At almost the same instant that Nasty is awakened, Kim and Lloyd step outside the lounge. Kim wants to show Lloyd the changes he has made to convert his ’36 Harley to electrical starting. As he bends over to point out a wiring detail, he feels a searing blow at his waist and tumbles down. Lloyd, too, falls, struck by a bullet that enters his chest and dances across his body, exiting at his shoulder. Gravel flies about them, kicked up by automatic-rifle fire. By the time the others reach the front door, pistols in hand, the assailants have driven on down Jacksboro Highway. Later, the Bandidos easily connect the two events: whoever torched Nasty’s garage drove immediately to the lounge and opened fire on the Tobins. The attacker, they reason, was probably the same man who shot Johnny Ray Lightsey off his bike. Kim and Lloyd are hospitalized, and once again the Bandidos sleep with their pistols.

Two nights later, Big Jim squats in the kitchen of E. J.’s house, over his cycle work. That afternoon he welded up the cracks in the bike’s frame; now he is picking at the transmission. Earlier that night, another club brother kept watch on the house, but now it is nearly 4 a.m., too late for prudence. Big Jim is out of cigarettes, and neither Doe, sitting tiredly at the kitchen table, nor the Bandidos drinking in the living room have any left. Jim and Doe decide to buy more.

It is a somewhat ambitious plan. The only means of transportation at their disposal is Prospect’s battered old pickup, which he left in the back yard early that evening. It has a leaking radiator hose. But he can drive it, Big Jim thinks. He’ll have to remove the hose, cut away its tattered end, and clamp it back on again. He picks up a screwdriver and steps out the back door, onto the porch. Doe is a few steps behind him. As he turns toward the pickup, he sees a flash and hears a boom. He collapses back into the doorway. Blood jets from his belly.

Before he can clutch the wound, another flash comes, from a shotgun about fifteen feet away. This time his forearm is hit. “Get out of the door!” a Bandido yells from inside. But Jim can’t move. He falls backward through the still-open door, landing beside his engine. There is another boom; this time, his side is crushed. He leans his uninjured right arm over the Harley engine, lying down, playing dead. Now he hears return fire. Two Bandidos are at the kitchen window, discharging their pistols at a figure in the darkness.

A moment later, there is silence. The assailant has run away.

Doe has turned away from Jim; she is weeping.

Jim, still conscious, shouts for an ambulance. But already his vision is blurred.

“E. J., brother E. J.,” he moans.

E. J. kneels at his side, a revolver in his fist.

“Take it easy, brother. We’ve called an ambulance for you.”

“E. J., you take my bike. It’s yours, brother.”

“Nah, no need to say that, brother,” E. J. mumbles. “You’re going to make it all right,” he says, not believing himself. He looks around the room; all the other Bandidos are worried, too. No one thinks Jim will live. Doe will not look his way. She moans as Trisha comes and leads her off to the bedroom.

Jim does not lose consciousness. When the ambulance comes, he asks the driver to let E. J. ride along to the hospital. But E. J. does not go to the hospital, not immediately. There is other business to take care of. The cops are searching the kitchen, demanding to see the weapons the Bandits used in self-defense. And there’s the matter of the dog, too. E. J.’s black-and-brown mutt failed to bark when the phantom gunman came into the yard. As soon as the cops are gone—taking one Bandit pistol with them—E. J. paces up to the dog, which is playing at another Bandit’s heels. When the animal looks up at him, E. J., with a swift, straight-armed motion, aims his revolver and fires. The dog falls dead without a whimper.

“I never gave that dog a name,” E. J. explains to his startled club brother. “But now I don’t have to. We can just call him Dead.”

And a few seconds later, he adds, “Yeah, and the same goes for the dude who shot Big Jim and Kim and Lightsey. We’ll just call him Dead, too.”

Half an hour later, two patrolmen in Richland Hills on Fort Worth’s northeast end stop their car behind a van parked in a lower-middle-class residential district. The garage doors of the nearest house are open, and so are the rear doors of the van, which carries two Harleys. Suspecting a burglary, the patrolmen question the tall, long-haired man attending the vehicle. By radio, they ask for a registration check on the motorcycles. Their suspect, Steven Daniel Vance, 22, turns out to be a resident of the nearby house. But both motorcycles were reported stolen earlier that week. Vance is arrested for theft.

The two patrolmen search the van for other contraband and weapons. They find six handguns and a twelve-gauge pump shotgun. All are loaded, the shotgun with green Federal Express shells like the spent cartridges found in the yard where Big Jim was shot. The weapons are turned over to Fort Worth investigators for ballistics testing.

Two days later, Vance is charged with the shooting death of Johnny Ray Lightsey. Fort Worth homicide officers say that bullets fired in ballistics tests of a .38 caliber pistol found in the van match up with slugs taken from Lightsey’s body. They also report that marks on shells fired from the suspect’s shotgun match those on the spent ammunition found where Big Jim’s assailant stood. In addition, bullets fired from the semiautomatic rifle taken from Vance pair with a slug in Kim Tobin’s bloodied leather jacket.

Though the evidence neatly implicates Vance, it is unlikely that he was the only actor in the Bandido shootings. Fort Worth homicide investigators and Bandits alike believe that at least two men are responsible—one who drove the vehicles from which Lightsey and the Tobins were shot and one who fired upon the victims. The Bandits also believe that Vance could not have been alone that night North Richland Hills policemen arrested him: unloading motorcycles from a van is ordinarily a two-man undertaking. Vance, however, refused to discuss his associates or accomplices with prosecutors. All winter he was mum as he sat in jail awaiting trial.

For several years both police and Bandidos have known Steven Daniel Vance as Trapper John, a member of the Ghost Riders club, a local organization which, though originally formed as a Bandit farm league, has drifted beyond the control of its founders. The Ghost Riders have in recent years been closely allied with the Dallas Banshee chapter, which is also hostile to Bandits. On the night of July 9, 1977, outside a bar on Harry Hines Boulevard in Dallas, Steven Vance was wounded by a shotgun blast fired from a passing car. A police report filed on the incident indicates that Vance told investigating officers the Bandits had shot him.

The morning after Johnny Ray Lightsey was killed, two Banshees were shot off their motorcycles at Madisonville, between Houston and Dallas. One of them, before he died, identified his attackers as three men in a tan Lincoln Continental, and gasped, “The Bandits hit me.” Banshee national president Ronald Bush took up the accusation, telling reporters, “The Bandidos don’t want any other motorcycle club in Texas and the only way they can get us out is to kill us off.” He further said that if the Bandidos wanted war they would get it.

An Austin Bandido who drove a tan Lincoln, and who had business dealings in the Fort Worth–Dallas area, Jan Colvin, 31, turned up dead on a vacant lot in Irving last November. His death may be part of a Banshee “payback” for the Madisonville killings. But Bandidos believe Colvin was killed by disgruntled business associates, not Banshees.

The Texas Bandidos enforce a hegemony all their own over the 75 other outlaw biker clubs in Texas. Bandidos forbid members of other clubs to wear various regalia items on denim membership jackets, or “colors.” On the list of prohibited adornments are rocker patches that say Texas—for the Bandidos consider that their native, exclusive turf. Last spring, the Fort Worth Bandidos demanded that a midcities club of black bikers, the African Bandits, change their name. To avoid war, the blacks chose compliance: today they call themselves the Mandinkas.

The clubs that Bandidos regard as imitators sometimes pull public stunts, like beer raids or showdowns with the police, which the Bandidos believe are best left to experts like themselves. As the Bandidos see it, the trouble always comes home to them anyway, no matter what club is involved. They say that practically every crime committed by bikers in Texas is attributed to them, because they are the most notorious club in business. Taking the heat for others, the Bandits believe, gives them the right to call the shots.

Dozens of smaller clubs have been absorbed into the Bandidos. But from time to time, other clubs have defied Bandido dictates. Almost every member of the Fort Worth Bandit chapter has “battle patches” sewn on his jeans, patches forcibly taken from the members of other clubs in sovereignty disputes. The chapter’s battle flag, too, has its swastika surrounded with such trophies—patches taken from the Ghost Riders, the Diablos, the Damned Few. Some clubs, like the Freewheelers, though still organized elsewhere in Texas, no longer have chapters in Fort Worth because absorptions and forcible “patch pullings” have decimated their numbers. Like Jim, who was a Freewheeler, most Fort Worth Bandidos once rode with smaller clubs.

The Bandidos frequently fight with the members of other clubs, but usually win, and they are probably right to believe that none of the other clubs are nervy enough to declare an all-out war on them. That is why, from the first, they have suspected that Lightsey’s killers were individuals seeking to settle some private score—a private score against Bandidos, perhaps, but not a club complaint. In their own search for the men behind the Fort Worth shootings, they are looking for Vance’s friends, not for fellow club members or allies. All winter long they kept their ears open to rumors, but apparently learned little.

The winter was not a good season for the Bandidos. Kim, when he recovered, was brought to trial for the rape alleged to have occurred at Trader’s Village. Despite protestations from Herbie Brown and the other Bandidos that Kim had nothing to do with the Dallas woman, Kim Tobin was convicted of raping her and was sentenced to an eighteen-year prison term. Weird Larry, or Larry Dale Sparks, was also placed in the dock for a chili cookoff stabbing. Though eligible for parole, he was handed down a seven-year sentence.

Steven Vance initially fared much better in court. Prosecutors did not ask for his indictment on the Tobin shootings, and a grand jury no-billed him for the Lightsey murder. On January 26 he pleaded guilty to the shotgun shooting of Big Jim Bagent and received a probated ten-year sentence. As soon as he left the jailhouse, he went into hiding from the Bandits and, perhaps, from everyone except his attorney and probation officer. But twelve days later he was behind bars again. Local officers working on a felony fugitive warrant picker him up for return to Louisiana where he had skipped out on a one-year probated sentence for drug possession. At his new midcities apartment they found a van reported stolen from a Dallas floral shop a slim three days after his release from custody in Fort Worth. Probably because he suspected the Bandidos were trying to hunt him down, Vance was well armed. The police took a .357 Magnum revolver from him at the door of his apartment; inside they found a sawed-off shotgun and a rifle. All three arms are forbidden to probationers, and mere possession of the short-barreled shotgun is an offense. Trapper John will be a prisoner for years to come, but at least guards will stand between him and the Fort Worth Bandidos, even if they all meet up in Huntsville.

If better days were ahead for the Fort Worth Bandidos over the winter, the first sign came from Houston. Bandido national president Ronald Hodge of Houston sent the Fort Worth chapter a new leader, Butch Goodwin, 34, a stocky, bearded ex-convict with the words “I love my Bandit brothers” tattooed on one arm. Goodwin put a stop to the chapter’s laxity: its members began riding armed and in pairs. Not a shot was fired at them, perhaps because Vance’s accomplices were cowed or because they simply lost heart when Trapper John was jailed. Then in mid-March, Judge Howard Fender overturned Kim Tobin’s eighteen-year sentence and Kim was freed on bond. There is little likelihood that he will ever be brought to court again for the alleged Trader’s Village rape, but the trial had cost Kim his most precious resource. On the Sunday after his release, he sold his Harley to pay off his attorney’s fees.

Three months after his wounding, Big Jim, flanked by Butch and E. J., paid me a visit. His comrades helped him up the front steps, and Jim came through the door gingerly, balancing his hulk on a four-pronged cane. I received these Bandidos from my bed, where I lay recuperating in a body cast, the payoff from an October head-on crash between my own Harley and a pickup. E. J. and Butch quickly left to carouse in Austin’s topless bars, while Jim and I talked until daybreak, empathetically trading hospital trauma tales. He showed me the gashes surgeons left on his abdomen, the cast covering the bone blasted out of his arm, the brace on his paralyzed left foot.

He had suffered in other ways as well. His old Datsun was repossessed and Doe left him. Jim had no insurance, but he believes that he has something better, the Bandidos. “You know, I haven’t had a cent all this time. My brothers give me what I need,” he told me.

Jim did not want to talk about anything he might have known about Vance or his phantom accomplices. When I asked him why he was shot, his answer was evasive, if witty:

“I really don’t know why they did it, but I’ll tell you one thing, that’s what. I don’t think it was no accident, they convinced me of that.”

E. J. also told me little.

“If we ever find out who was involved, I can assure you that he will be duly reprimanded,” he said.

Bandidos I spoke with later were equally sly and closemouthed, and that is as good an indicator as any that if they can, they will carry out a vengeance in their own style. Their judgment, we may assume, will come as a crack in the night.

*This name and the names of a few other places and people occurring later have been changed.

The Harley Grail

Even bikers have a church. Where else could they drink tax-exempt beer?

Fighting and feuding, always competing for control of their territories, motorcycle gangs are hostile, sometimes violent, rivals. But one day every week, on their sabbath, bikers of every persuasion put aside their hostilities and come together to pay homage to their one true god, Ralph. The holy see of the First (and only) Church of Harley-Davidson is Denton, where each Friday night First Churchers congregate at one of two watering spots, the Crossroads and Benny’s. “We’re mainly a beer-and-reefer church,” says founder Malvern Daugherty, 31, better known to his followers as Reverend Box. The Reverend and his co-pastor, Blue J. Murphy, an Irving police patrolman before his conversion, pass an offertory hat. “Give freely, give freely,” Reverend Box urges the flock. “After all, your tithes are tax-deductible.” These tax-deductible tithes are used to buy beer, which is consumed in communion services celebrated in the homes of the faithful. The masses begin at midnight, closing hour for Denton bars. Glossolalia is profuse by the time the spirit takes hold, usually by 3 a.m. “I get as stinking drunk as I can,” Reverend Box confesses.

The First Church is ecumenical—by biker standards, anyway. Among its two hundred followers are devotees of the Bandidos, Scorpions, Ghost Riders, and other rowdy Fort Worth–Dallas motorcycle cults. Even riders of Japanese bikes are let in—testimony to a missionary zeal or a liberality that is viewed as high heresy by ordinary outlaw biker sects. “Hell, we’ll take in anybody who’ll behave right. We’ve got a few members who don’t even ride bikes,” Reverend Box says.

Though he founded the church eight years ago, Reverend Box has not succeeded in imparting theological orthodoxy to his followers. “I’m not so sure about some of the others, but I’m a confirmed heathen,” he explains. Some members of the flock, but not all, share with Box a faith in Ralph, the Harley god. The pious believe that Ralph abides in the innards of every throbbing Harley engine, and that he is a jealous and exacting god. In order to worship him, Harley owners must kneel and carry out monkish acts of ritual devotion, like changing oil, tuning up, and keeping Ralph’s motor-temple clean. “The more religiously you carry out maintenance, the more Ralph smiles on you,” oracle Box proclaims. Inspired study of the Harley repair manual is considered necessary to gain Ralph’s grace.

First Churchers fear Ralph’s wrath, which a few of them have suffered firsthand. “You’ll be puttin’ down the road one day when all of a sudden your motor will thunder out ‘Rraaaallphh!’ That’s his punishment for infidels. You’ll find that your motor won’t run anymore, if it’s in one piece, and as for Ralph, he’ll be gone from it, back to his celestial home.” This vengeful visitation, Box says, is called “Ralphing it on the road.”

In addition to Friday night services, Reverend Box and Reverend “Blue Jay” perform weddings (three in the past eighteen months) and in sacramental fashion dish out chili—even to the unsanctified. It was Reverend Box who invited the Fort Worth Bandidos to break bread at last year’s Trader’s Village chili cookoff, precipitating a riot. One of the Harleyite chili deacons won first place honors and another came in second in the jalapeño-eating competition at the 1978 San Marcos Chilympiad last September. Reverend Box says both cookouts are on the First Church calendar again this year.

Stewardship of First Church coffers is a simple matter. Both Reverend Box and Reverend Blue Jay are ordained ministers of the tax-gimmick Universal Life Church. The Harley congregation owns no property other than a beer box. When beer is bought for ceremonies, Box and Blue Jay save the receipts. Before reckoning day, each April 15, the pastors file a tax statement with the IRS. Within weeks, Uncle Sam sends them a refund for the excise and sales taxes paid on liquor purchases. This year, Box estimates that the First Church will be refunded some $200. All of which, of course, will be promptly committed to glorifying Ralph’s holy name.

D.R.

You Are What You Ride

Why you don’t meet the nicest people on a Harley.

To the deep disgust of every outlaw biker, Japanese motorcycles have taken over the American market. Their advertising is everywhere, always insinuating that if you own a Kawasaki, a Suzuki, or a Honda, you will be popular and meet interesting people who, no doubt, are vegetarians and joggers. The slogan “You meet the nicest people on a Honda” may have sold lots of bikes to respectable suburbanites, but it also explains why most outlaw bikers would never ride a Honda. Horses made the Comanches the masters of the plains, and Harleys give their riders superiority over all living creatures. Right-thinking Americans, especially Bandidos, know this is true.

Lone Star drinkers, Adidas wearers, and Fleetwood Mac fans sport their loyalties and good taste on T-shirts, but no cult compares with Harley-Davidson’s. Without any authorization from the motorcycle maker, devotees and profiteers have spawned a thriving commerce in rings and earrings, caps and gloves, ashtrays and beer steins, patches and hashish pipes, even panties and bras, all emblazoned with the winged Harley trademark. As a tattoo, the Harley emblem is more in demand than the Navy anchor or the Marine Corps bulldog—or even “Mother.”

The machine behind the Harley mystique is a 650-pound roaring motorcycle with a two-cylinder engine. Like that other air-cooled classic, the 1200cc Volkswagen engine, the Harley motor can be endlessly rebuilt. Thousands of forty-year-old Harleys are still on the road, but there is no such thing as a vintage Honda (the first one wasn’t built until 1948), and there never will be. Honda has produced so many models that none of its dealers can afford to keep all parts in stock. Harley produces only three motors. Some parts for it can be found at auto supply houses, and nearly all are on the shelves of dealerships. Bikers hoard and trade old Harley parts; junkyards take in old Hondas, which are built to sell, not to last. Harley handlebar tubing is bigger, so the bars won’t break. Airplane bolts with reinforced heads are used on Harleys, but not on Hondas; many who have worked on the rice-burners have had stove-bolt heads break off in a wrench. There are plastic body parts on Hondas, but not on Harleys. The gearshift, clutch, and brake levers on Hondas are likely to bend or crunch off in a spill, but Harleyites ride away from accidents. A Harley is a machine your grandchildren can inherit when you’ve ridden it to your grave. About the only thing a Honda is good for is riding to work, because Hondas don’t break down—for three years, after which they rapidly turn to trash. But real bikers don’t work, or ride disposable motorcycles, either.

Honda now makes a machine with a 1047cc displacement that some misguided people claim rivals Harley’s performance. Of course, if you want a four- or six-cylinder engine that sounds like a sewing machine, has a radiator, a fuel gauge, and little lights to tell you what gear you’re running in, then, yes, you do want a Honda. Nobody who rides a Honda smokes real cigarettes, but if you want a Honda and you do smoke, you’d better get a purse to carry your low-tar brand in, for a very simple reason: Harley T-shirts, made only in black, all come with cigarette pockets. But Honda T-shirts come in white and rainbow colors, and you’ll have a hard time finding one with a pocket. And that explains the difference between Honda and Harley—Honda has no class.

D.R.

- More About:

- Longreads

- Fort Worth