This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The greatest friendships are sometimes the most unlikely, and in this category we can speak of the relationship between Rex Cauble and Muscles Foster—one of them (Rex) being a member of the Texas super-rich with an established reputation as a fanatic against the use of marijuana, and the other (Muscles) being a rumpled, slightly crazy cowpoke who was the admitted ringleader of probably the largest dope smuggling operation in the state. At one of the trials psychiatrists would call their friendship “a father-son relationship,” but psychiatrists have a way of boiling off the broth to get to the bone. Muscles did need the guidance of a successful older man, since his own father’s tragic example was nothing to emulate, and certainly Rex craved devotion. What each of them needed, however, was less than what he found in the other. It was an extraordinary friendship.

They don’t see each other anymore, of course; it’s not possible with the siege of federal agents at Rex’s door. It has been nearly two years since Muscles’s dope ring was broken, and since then the government has poked into every corner of the Cauble empire, looking for evidence that would establish Rex—owner of several ranches and Cutter Bill Western Wear stores, former chairman of the Texas Aeronautics Commission, political friend of John Connally and other notables, and possessor of a vast fortune—as the kingpin of the narcotics underworld in Texas. It’s easy to believe that Rex wishes he had never met Muscles Foster. Rex sits in his Denton office surrounded by civic awards and photos of the rich and famous, and yet there is an emptiness in this sanctum that is as keenly sensed as the clamor of the grand juries outside the walls. Muscles is missed.

They met somewhere in the grandstands of the horse business in 1960. Rex was a square-faced oilman with bushy eyebrows and a big-shot cigar, and although he was only a neophyte breeder of quarter horses at the time, he had ambition and a fortune to spend. Already he owned some of the most famous studs in the industry, including Silver King, Hard Twist, and even the great Wimpy—the original stud of the entire quarter horse breed, who was twenty years old when Rex acquired him. But it was a young palomino stallion named Cutter Bill that would make the Cauble stable famous in the horse world. When Rex and Muscles met, Cutter Bill was four years old and just beginning to show the form that would make him the world champion cutting horse and set a record for money earned in a single year of competition. Cutting, in horseman’s parlance, means picking a calf out of a herd and holding it apart, one of the fundamental skills of a good cow pony. The first time Muscles watched Cutter Bill perform, he realized that the horse would become a legend.

Women and Horses

Muscles knew horses. He had grown up in the rodeo, riding bulls and broncs for not much money. His real name was Charles, but the cowboys called him Muscles, which was a joke of sorts, since he was slightly built and weighed about 130 pounds. He had big ears, a goofy grin, and shoulders that rolled forward from slumping in the saddle so that he stood in the shape of a question mark. Muscles had traded his first horse before his voice broke—for a $90 cow and a Mickey Mouse watch—and from then on he knew he had a gift for buying low and selling high where horses were concerned. Some of the big men of the Texas horse world, the Caruths and the Phillipses, extended lines of credit to Muscles to buy mares for them, and he quickly earned a reputation as one of the sharpest traders in the country. Soon after they met, Rex became another of Muscles’s millionaire clients.

Rex and Muscles grew close, but not in the way of business friends. It’s a common observation that rich and powerful people surround themselves with obsequious, ego-dependent individuals who trade flattery for access to monied society. Muscles was certainly willing to make that trade, although his feeling for Rex was more complex than the adoration of a sycophant.

Muscles had barely known his own father, except as a darkly raging drunk. When he was ten years old his mother took him and his three sisters out to U.S. 80 in front of their home in Mineola and hitched a ride to Dallas. Four years later Muscles ran off to rodeo in Oklahoma. Small as he was, Muscles could ride with the best; one year his winnings put him within a few dollars of the world bull riding championship. Then he suffered the first of three bad marriages, this one lasting only two weeks. He returned to Dallas and learned that his father had died in Terrell State Hospital. By then he was worried that his own life was following the same sad script to the end.

“Through large and frequent donations, Rex had become allied with some of the most influential politicians in the state—notably John Connally.”

With his amiable smile, Muscles made friends everywhere he went, and yet inside he was a brittle man with a single great weakness: women. He was their devoted fan. The sight of an approaching female filled him with hope and unbearable anticipation. If she even remotely fulfilled the promise of his imagination at fifty paces, his jaw would drop open with admiration; a few steps closer and his love was in full bloom and his hand was reaching instinctively for his wallet. Money was his standard approach to women. He was not a handsome man—there was something monkeyish about him, with his small head and long, dangling arms—and like many ungainly people, he idealized beauty and imagined that whatever interest a woman had in him was a charitable form of corruption. He would promise them anything and give them all he had—this horse trader, who was so canny in one sphere of his life and so loony in another. When the promises rang hollow and the money ran out, the women would leave him and Muscles would go into a decline. He would mope and moan for a while, then suddenly disappear. Sometimes he would be gone for months. Finally he would return, full of Oregon or Maryland or some such place where he had passed a little time and made a few friends and then vanished as abruptly and inexplicably as he always did.

The last woman who married him actually stuck around long enough to bear him two sons; then, in 1965, they were divorced and she left, taking the boys along. Muscles shattered like a china saucer. This time he did not wander into Oregon. He called for help, and the man he turned to was Rex Cauble. Rex had suffered his own trials in marriage, so when Muscles called and began to sob on the phone, Rex told him to pull himself together, he’d be right over. “It’s not the end of the world, Muscles,” Rex told him when he got there, but Muscles was disconsolate. He walked around the house wringing his hands and weeping, “like a wet dishrag,” Rex later said. Finally Muscles got around to asking for money—he planned to lure his family back in the only way he knew how—and Rex wrote out a check for $9000. Muscles’s wife spurned him but took the money, and soon after that he tried to commit suicide. He was taken to a Dallas sanitarium in a straitjacket, having convulsions and foaming at the mouth.

Most of his friends thought he was just off on another jaunt, but when Muscles returned months later they realized that he was a changed man. He was bland-faced and had trouble remembering names. It was the shock treatments, he apologized. He told his best friend, Willis Butler, that it was like having his mind erased, but of course some of the memories wouldn’t go away. Although he had never been a drinker (years after a teenage encounter with white lightning, a whiff of whiskey still made him queasy), he now discovered the gentle anesthesia of rum and Coke. Upon Muscles’s release from the hospital, William Caruth, another millionaire who was fond of him, let him use his Saber Ranch, the Dallas landmark directly across the highway from NorthPark shopping mall, but Muscles stayed drunk and left the property a mess.

When Caruth booted him out, Muscles went to Rex and asked for a job. Rex hired him to breed mares and break horses. A few months later Rex promoted Muscles to be the overseer of all his property, which included several large ranches and many smaller lots around the state.

It is hard to figure out what Muscles and Rex meant to each other. Rex had an explosive temperament, and nobody made him angrier than Muscles, whom he found “loyal, obedient, and undependable.” But since he valued the first two qualities so highly he suffered the third. “He thought a lot of Muscles, but, I mean, he would talk to him like a kid,” one of the cowhands later testified. “He’d talk to him pretty hard. I would have quit, but Muscles didn’t.”

Muscles dreaded those blasts from Rex. “If you ever had your ass chewed out by an expert,” he recalls, “you can say one thing: he’s second to Rex Cauble.”

During the late sixties Rex acquired a steel company, a welding company, and a horse trailer company in Fort Worth, and his Cutter Bill Western World stores in Dallas and Houston became famous. They featured fancified Western clothes at extravagant prices—“the Neiman-Marcus of Western wear,” they were called by the Los Angeles Times. He also ordered an architect to build the most splendid stable in Texas beside the interstate north of Denton, on the ranch where he lived. The stable had its own show ring and a trophy room for the ribbons and loving cups his horses brought home. On the roof he had painted, in enormous black letters legible only to airplane passengers, CUTTER BILL CHAMPIONSHIP ARENA, and in front of the stable he erected a gilded statue of his palomino stud, which twinkled in the sunlight like a yellow god. Rex could boast assets of the $80 million, and yet every Wednesday that Muscles was in residence at the ranch—he lived in the guest house—the old man would stop by and pick up his laundry.

Rex the Two-fisted Chairman

Through large and frequent campaign donations Rex had become allied with some of the most influential politicians in the state—notably John Connally, whose picture is as ubiquitous in Cauble’s many offices as photos of the president are in the warrens of the federal bureaucracy. When Connally made his first run for governor in 1962 he asked Rex to be one of his campaign coordinators, and after he was elected he appointed Rex to the Texas Aeronautics Commission, which was a small-time agency that built boondocks airports—until the following year, when some of the governor’s friends and business associates invested in Southwest Airlines stock. Then the TAC became quite a conspicuous place to be, especially during Rex’s tempestuous reign as chairman, when he forced through rulings in favor of the infant commuter airline and once pushed out another commissioner who had posed an objection concerning the use of the TAC staff. The press began referring to Rex as “the two-fisted chairman,” which very much corresponded to his image of himself.

Rex also became a member of the Special Texas Rangers, an organization of law-enforcement enthusiasts—cattlemen, corporate executives, and lobbyists—who were allowed to carry guns and badges and even to dress like Rangers. Rex subsequently got acquainted with some of the characters in the Department of Public Safety’s narcotics division, a netherworld of hustlers and sharks who were nearly indistinguishable from the element of society they were supposed to police. Rex had always had an affinity for the rogues and the con men who were an established part of the high-rolling fraternity of Texas oil barons, in which Rex was a charter member. He became a patron of the DPS narcs, using them for part-time security work and frequently lending them flash money and the use of his plane. At one time he had four ex-DPS agents working for him.

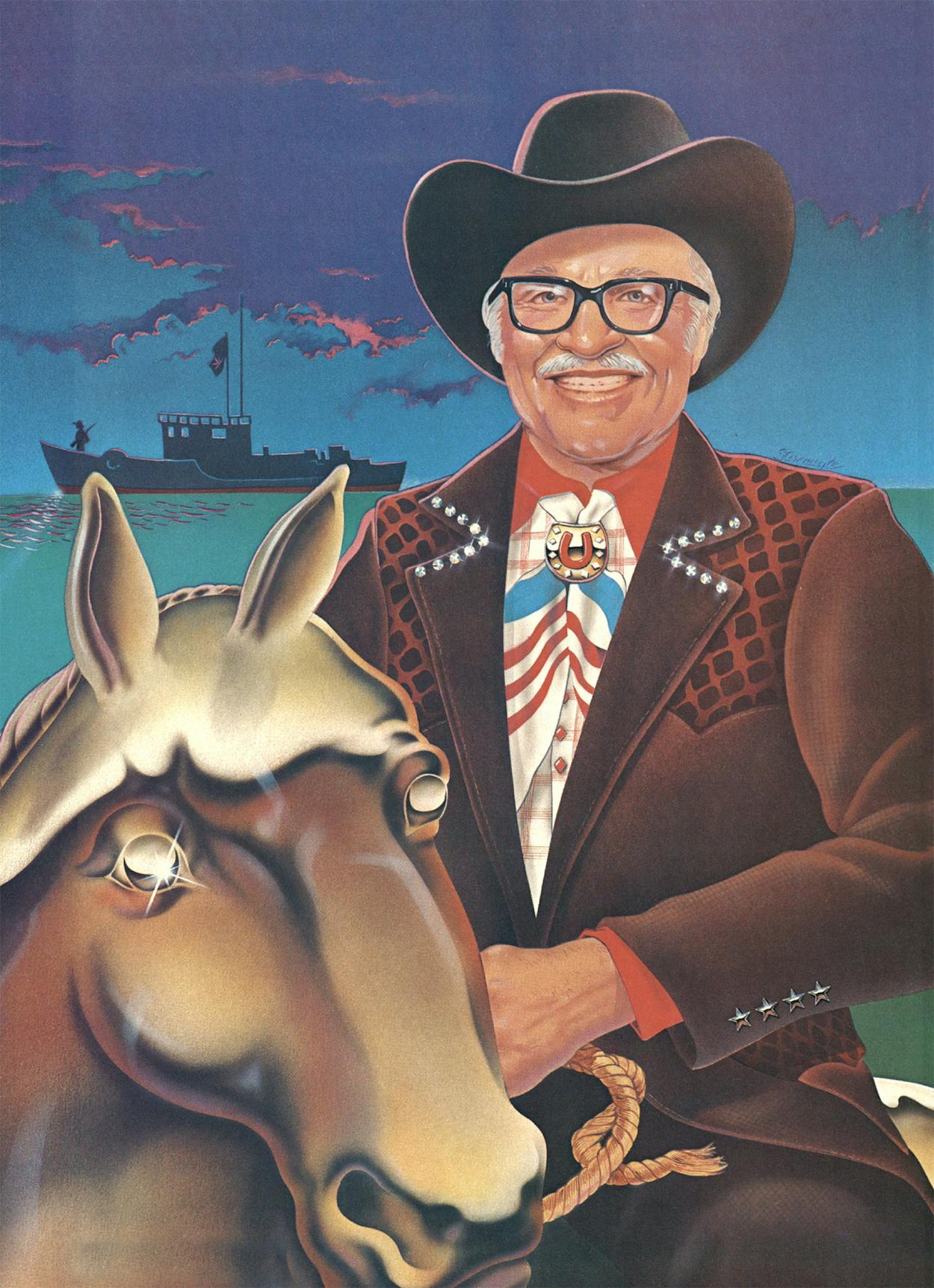

Rex seemed fascinated by the violent world these men inhabited. They made him an honorary member of the Texas Narcotics Officers Association, and he threw parties for them in his Denton show barn. He liked to appear at these shindigs dressed in flamboyant Western outfits from his Cutter Bill stores, and if he sometimes felt a little false in his jeweled suits and python boots, the fact that he could play Daddy Warbucks to some of the roughest cops in the state gave him a feeling of true-grit legitimacy. The highlight of the parties was the appearance of Manuel T. “Lone Wolf” Gonzaullas, a legendary Texas Ranger. Once when Rex was still just an oil field bum, Lone Wolf had chased him off a freight car. He was aged now, but he could still shoot with either hand and he still walked stealthily, as Rex remembers, “like he was walking on eggshells.”

Rex brought glamour to Denton, and Denton liked it. His parties glittered with Texas society, and Rex’s money and position became a kind of symbol of the greater aspirations of the small college town. Rex represented Denton in the same way that his stud Cutter Bill represented his own desire for graceful possession of power.

Enter the Smugglers

Over the fourteen years that Muscles worked for Rex, his responsibilities increased until he either controlled or had access to the entire Cauble empire—the ranches, the airplanes, the stores, and also the Long Branch Saloon, a Denton night spot that Rex established to provide for Muscles’s retirement. And yet, as great as his authority was, he could never string more than a few months together at a time before he would disappear, usually just when Rex was trying to coax him to go into the hospital. Muscles was terrorized by the shock treatments; he said they were killing him, that he woke up in the morning after a treatment and just felt like dying. When his black moods started to close in on him, Muscles would walk out to the interstate and stick out his thumb. Rex would curse his name for weeks, and then in the middle of the night a collect call would come from the bus station in some godforsaken landfall and Rex would wire him the dough to come home. Muscles was in his forties, but he called Rex “Poppa.”

Once Muscles went over the hill carrying the keys to every lock on the ranch and leaving in the lot nineteen mares that he had bred to three different studs. Rex had a devil of a time getting the breeding straight. A couple of weeks later the keys arrived in the mail and Rex blew up again. Muscles finally turned up in Georgia at the ranch of Ray Hawkins, who seemed to be part horseman and part hippie—a long-haired cowboy whose principal asset was a quarter horse stud named Tardy Too. Hawkins had come to Denton to buy a horse from the Cauble stable, and Muscles may have learned then the source of his sizable income.

Also visiting the Hawkins ranch at the time were Carlos Gerdes and Jamie Holland. Carlos was a good-looking Latin who was experimenting with organic gardening. “He was dead serious about it,” Muscles says. “He would work his tail off to grow a single cucumber.” Jamie Holland was quiet, sullen, and extremely muscular—“healthy,” as Muscles describes him. Muscles noted that, like Ray Hawkins, Carlos and Jamie seemed to have quite a lot of money, considering that they were so young and apparently unemployed. It was an observation that many people were beginning to make, not just about Muscles’s acquaintances but also about the hundreds like them in Florida and California, and in Texas as well.

In the early seventies some of these young men were living on the Gulf Coast of Florida when somebody realized that the local shortage of marijuana might be eased by making a quick run to Jamaica, where grass was plentiful and sold for $10 a pound. They made the trip in a 28-foot boat and unloaded their conspicuous cargo on the docks of the marina in the Tampa Bay area. On that day the modern age of marijuana smuggling was born.

If Carlos Gerdes was not present at the birth, he certainly attended the infancy. One of his friends estimated in court that Carlos made at least $10 million in smuggling. In the St. Petersburg area he became known as an eligible young bachelor with money. Through one of his sweethearts he met Jamie Holland, who was dating her sister. He also met John Ruppel, a distinguished-looking white-haired man in his late fifties whose name, along with Rex Cauble’s, would one day surface in the hearing room of a New York grand jury investigating the narcotics underworld.

The geographical advantage of basing a smuggling ring in Florida was its proximity to the Caribbean, but by 1975 the U.S. government had largely destroyed the Jamaican pot fields, sending most American buyers to Colombia. At the same time, the State of Florida had instituted more stringent drug laws, and big-time smugglers like Carlos were lying low and looking for a new base of operations. So when Muscles appeared on the scene, carrying the keys—both literally and figuratively—to the Cauble empire, he seemed to offer the perfect solution.

“Florida’s big-time dope smugglers wanted a new base of operations. When Muscles appeared with the keys to the Cauble empire he seemed a perfect solution.”

Muscles claims even now that he went to Georgia only to break horses. While he was there, however, an agent of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation who was keeping Carlos under surveillance thought to write down the license number of the Chevrolet Suburban that Muscles was driving. It was registered to a horse trailer company in Fort Worth. After the computer had done its work the name of Rex Cauble made its first appearance in the records of narcotics agents all across the country.

Waiting for the Monkey

The government’s case against Rex really begins immediately after Muscles’s return to Denton in 1976. According to Rex, Muscles said he was interested in going into the shrimping business, and as unlikely as that might have been, Rex contacted a boat broker in Aransas Pass and told him that Mr. Foster would be in touch with him about the purchase of a shrimp boat. Muscles went down to meet the broker, and soon after that, in August, Carlos Gerdes and John Ruppel appeared and purchased a steel-hulled shrimper called the Monkey.

In December Muscles visited Willis Butler. As teenagers, Willis and Muscles had spent some time together in the care of Bob Grant, who was part owner of the Mesquite Rodeo and a man beloved for his care of misplaced youngsters like Muscles. Willis was near to being a brother to Muscles. “I loved Muscles,” Willis later recalled. “I would get so mad at him I could kill him, but we have been down a lot of roads together.” They had even gone into the “lead business” together at one time. In the lead business you sell worn-out car batteries to a smelting plant, which salvages the metal. Willis by this time had graduated to the “milk business”—he was driving a dairy truck—and Muscles also had a good job, with Rex. But his pockets never jingled when he walked; he simply couldn’t keep money together. For him it was like raking leaves in a high wind. So Willis was surprised when Muscles appeared with a cashier’s check for $15,000 drawn on the Denton bank owned by Rex Cauble. He told Willis he was on his way to Colombia to set up a dope deal.

It is worth a pause to wonder why Muscles ever got involved in the marijuana business. Cowboys were smoking pot long before it was fashionable in Haight-Ashbury, but Muscles never had a taste for it. His stomach was too delicate and the odor made him sick. Muscles loved money, but what he loved most about it was giving it away; you couldn’t say he was a greedy man. He says he became a smuggler for the adventure. His psychologist says he did it because he was grandiose and not “rule-governed.” The government would suppose that he did it for the same reason he did most things in his life: for Rex.

Two months later, in February 1977, Muscles was back in Texas and on the phone to Willis. He had some “errands” that needed doing in the Beaumont area, Muscles said, and he was willing to pay $50,000. Willis was on his way. Muscles stationed him out on Sabine Pass with a pair of binoculars and told him to watch for the Monkey and contact the crew when it came into view. Unfortunately, that first shipment was delayed, and it was three days before Muscles remembered Willis. He found Willis still there, asleep in his car on the side of the road.

They rotated watches after that. When it was Muscles’s turn he walked out to the end of a community fishing pier and just stood there, staring out to sea. One of the other smugglers suggested that he might be less conspicuous with a fishing rod in his hand, so he went to a sporting goods store and purchased seventeen rods and assorted tackle. He spent the rest of the afternoon trying to figure out how to rig his gear. The Queen Mary might have passed by and he wouldn’t have noticed.

But when the Monkey finally heaved into port, loaded with more than 30,000 pounds of marijuana, Muscles redeemed himself. He cleared out the foreman on Rex’s Meridian Ranch in Fort Worth so the smugglers could use it to divide the shipment and distribute it to the buyers. Willis drove the marijuana to the ranch in a tractor-trailer. Carlos kept the books and handled the distribution.

After the deal Carlos, Jamie, Ray, and some of the others went to Denton to celebrate. They stayed with Muscles in the guest house on the Cauble ranch, and one morning they all had breakfast with Rex himself. Hawkins told Rex he was in the market for land in Texas. Jamie and Carlos had already bought land near Gatlinburg, Tennessee, where John Ruppel had constructed a mountaintop palace. Jamie had plans to be a rancher, and Carlos announced that he was finally going into organic gardening in a big way. Rex later maintained that he had no idea what brought the young men to Denton—“They were just Muscles’s friends,” he claimed—although Ray Hawkins gave him $100,000 in cash toward the purchase of a ranch in Valley View, and Jamie Holland bought one of Rex’s prize bulls to get his own herd started. It may have been then that they planned their trip to Las Vegas, the natural conclusion of a big smuggle. In Vegas, illegal money is casually lost on the gaming tables or easily laundered as winnings.

The trip actually began with Carlos Gerdes in St. Petersburg; he and two of his partners chartered a plane to fly to Gatlinburg. On the way they drank whiskey and practiced playing poker, using real money that Carlos produced from one of his aluminum suitcases. Carlos always carried the money that way. “We discussed what a good suitcase it was,” Muscles remembers. “I thought it was hideous.” In Gatlinburg they picked up John Ruppel and switched to a Learjet, then flew to Love Field in Dallas, where they transferred to yet another plane, a Beechcraft with Cauble’s name written large across it. Muscles came aboard, and while they were transferring the luggage a woman drove up in Muscles’s Suburban station wagon. She was Fern Lynch, Rex’s girlfriend of long standing. According to John Ruppel’s testimony later, “they loaded several of these aluminum suitcases into her station wagon, and they talked and joked and she left.”

In spite of all the effort that the government subsequently expended trying to link Rex and Ruppel, investigators were never able to connect the two men in Las Vegas, although both of them made a practice of going there to gamble every New Year’s Eve—Rex called it “duck hunting” so his wife wouldn’t know. He stayed at Caesars Palace. Ruppel also liked to go to Las Vegas. He was there on New Year’s Eve, 1977, as were some of the other smugglers and also the boat broker who had sold Ruppel and Gerdes the Monkey. During the time the smuggling ring was in operation, Ruppel spent each New Year’s Eve in Las Vegas. Rex intended to go every year, but he was waylaid by surgery once and an ice storm another time.

Muscles made the first trip to Las Vegas dressed in his ranch clothes, with a pair of dime-store spectacles hanging on a shoelace around his neck. He had to borrow money to gamble, since he had already given $130,000 of his loot to his girlfriend. Carlos took pity on him. He hired a girl named Cookie and gave her several hundred dollars to buy Muscles some decent clothes. She selected a pair of silk shirts at $150 each, and Muscles wore them in the casino with his old jeans and a brand-new pair of jogging shoes.

Mick Jagger, a Poor Example

Jogging shoes? The hands on the Cauble ranch were embarrassed for Muscles, especially when he began a tentative jogging program, his old white legs looking like something that might have been chased out of a cave. The cowboys didn’t realize that Muscles was undergoing radical behavior therapy with Dr. Donald Whaley, who is a long distance runner and the director of the Center of Behavioral Studies at North Texas State University.

In 1974 Rex had solicited Doc Whaley to treat his son, Lewis Rex, who, Rex said, was “addicted” to marijuana. “He feels that marijuana has robbed his son of motivation,” Whaley said. “Actually, I diagnosed Lewis’s problem right away as Rich Kid’s Syndrome.” Whaley became an arbiter between father and son, and in gratitude they threw a charity benefit for Whaley’s center. Willie Nelson came to perform, and it was at the Nelson concert that Doc Whaley first met Muscles.

Partly because of his son’s drug use, Rex launched a campaign against marijuana. When Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones went shopping at Cutter Bill’s (the store is famous as a celebrity stopover), some of the salespeople drove him up to the Denton ranch for picture taking. Rex heard about it and hit the ceiling, saying that Jagger was a poor example for the nation’s youth. Rex had some of his best employees take a lie detector test to determine if they had ever used marijuana, and when the president of Cutter Bill’s failed the test Rex fired him on the spot. “I have never seen a person so fanatic against pot,” Doc Whaley remarked. Rex is like that: explosive and capricious. His naturally florid complexion reddens with anger until you think his face might split open like an overripe tomato. He would fire his best merchandiser for participating in what the world knows is accepted practice in the upper reaches of the garment industry.

He was determined to find a crack replacement to run Cutter Bill’s. In fact, he already had someone in mind, someone perfect. After all, who could represent the wonderfully profitable marketing alliance of cowboy nostalgia and disco trinketry better than the one and only original Marlboro Man?

The Marlboro Man

That’s how Les Fuller billed himself. To see was to believe: in his early middle age Les was lean and tall—six foot three—with a sharply modeled face resembling Paul Newman’s and the sun-etched crow’s-feet around the eyes that Marlboro Men always seem to have when they light up and stare off into the distance. And it wasn’t just that Les was good to look at. He was a fixture in the Dallas clothing world—a sales manager for Parade Dress, well liked and widely admired in the industry. Hiring Les seemed to be a smart move from every perspective. He was experienced, he had good connections, and, with his gold bracelets and necklaces, his open Western shirts, his swagger and aplomb, he was the very personification of the cosmic cowboy.

There existed between Muscles and Les an oddly competitive friendship that centered on their relationships with Rex. Although Les wasn’t a real cowboy like Muscles, he was at least an earnest imitator. He had learned to ride cutting horses, and one year his stallion War Chip won the cutting horse championship, just as Cutter Bill had done a decade before. Rex liked to imagine that he and Les had more in common than the heavy silver championship buckles they wore on their belts.

Muscles could not help envying the Marlboro Man’s rugged handsomeness and easy way with women. As Muscles skulked around the Texas coast overseeing his burgeoning smuggling business, he would sometimes sign himself Les Fuller—an absolutely stupid imposture, but one that was almost irresistible to Muscles. Perhaps it was while he was pretending to be Les Fuller that Muscles realized that the role itself was a fraud.

Les was in trouble from the moment he took the job at Cutter Bill’s Western World. “After the first thirty days he was there,” Muscles recalls, “I said to myself, ‘He’ll never make it.’ ” Les had the same feeling. Within six months sales were dropping off the charts and his self-esteem was racing after them. His friends say it wasn’t Les’s fault, that Rex was siphoning cash out of the stores and Les couldn’t keep up the inventory. Muscles claims it was because Les was such a snob—“He wanted to sell strictly the millionaire product.” In any case, Les blamed himself. The Marlboro Man facade crumbled with the first tremor of defeat, and the whole world could see the uncertain man inside. On April 12, 1978, Les sat down and wrote out a will on a sheet of legal-sized paper, then scratched off a final letter. “Dear Rex,” he began, “I failed you and I failed myself. For that I can’t go on, cause there’s no place for me. I’m truly sorry that I let you down. But believe me I really tried—I just never could get a handle on CBWW. You are a true friend—I hope you’ll forgive me—like you, I never could stand failure, but unlike you I failed!”

A few moments later Les emptied a bottle of Valium tablets and gave himself up to the darkness.

Mafioso Muscles

Muscles was a genius. The most dangerous part of the smuggling operation is finding a safe place to unload, and oh boy, did Muscles find a place. He combed the coast and came up with a spot near High Island, in the sparsely populated stretch between Galveston and Port Arthur, under a bridge that crossed the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway. You couldn’t see it from the bridge, and you couldn’t see it from the canal either, because Muscles had dredged an inlet off to one side. You couldn’t even see it when you got under the bridge, since the whole area was covered with scrub and weeds twice the height of a man. You just couldn’t see it at all. It was as if Muscles had found a seam between the fabric of real life and the fourth dimension, and in this invisible spot he built the Thompson Seafood Company.

The amusing thing is that Muscles occasionally insisted on bringing in seafood, something no one else was interested in. As many as four boats were making runs to Colombia, and every trip was worth millions. One of the smugglers later testified that they bought the pot in Colombia for $25 a pound and sold it in Texas for $200 a pound. “Expenses and everything would bring the cost up to about sixty dollars,” he said, which meant that the average load of 35,000 pounds would net $5 million.

Muscles was making a killing, and yet at the moment when he should have been his happiest he went into another decline, for the same old reason: his girlfriend had thrown him out of the house. In a state of depression he wandered up to Tennessee, and it was there that he met Leslie Sprinkles, a nicely formed blonde. Muscles persuaded her to come to Texas, and when they arrived he borrowed one of Rex’s ranches and “gave” it to her, along with a half-interest in the Long Branch Saloon, which Rex also owned. Muscles assured Miss Sprinkles that he was the majority stockholder in Cauble Enterprises and that he was just keeping ol’ Rex on as a sort of figurehead. He really did give her a $17,000 flesh-colored Cadillac, but he kept it in the garage so Rex wouldn’t see it. Muscles explained his caution by telling her that he was in the Mafia, and when her eyes got wide he allowed that he was the actual godfather.

Rex Enraged

Les Fuller was recovering under the care of Doc Whaley, who told him, “Get your life in order and quit being a showboat. You’ve got a tough job to do, and you’re only Les Fuller, not the Marlboro Man.” Rex had been terribly understanding. “We’ll just make out like nothing happened,” he said, and of course everyone was very careful around Les when he came back to Cutter Bill’s. Unfortunately, things didn’t get better; they got worse. It was only a matter of time before Rex would have to make a change.

Federal lawmen had already begun an investigation of Cauble’s enterprises, bringing with them a series of subpoenas for financial records and other documents. The subpoenas were shot through with references to Muscles Foster, and Rex must have gathered pretty quickly that the heat was on. The Texas Rangers had already stumbled onto some marijuana sweepings at one of the Cauble ranches, but the investigation had been dropped—perhaps because Rex was one of the principal sponsors of the Ranger Museum in Waco, or because of Rex’s long membership in the Texas Narcotics Officers Association, or because, the way the political situation was shaping up, Rex stood to become the next commissioner of public safety. He was a strong supporter of John Hill in his race for governor, and the rumor was that if Hill won he would put Rex in charge of all state law enforcement.

Rex called Muscles’s cronies into his office one by one and told them to stay away from Muscles because he was too hot. “I raised so much hell,” Rex later remarked, “that Muscles finally disappeared.” He sent one of his men to find him, and word came back that Muscles was hiding out at Les Fuller’s.

“On September 23, 1978, Rex Cauble called me into his office in Denton,” Les later told federal agents. “Rex jumped me about being disloyal and hiding Muscles.” The FBI was looking for Muscles, Rex told him, and so were the Texas Rangers. “I thought that was kind of funny because Rex could have the Texas Rangers find Muscles if he wanted to,” Les said. In the course of the argument Rex accused Les of faking his suicide because he “didn’t have guts enough to use the .357 Magnum” that he always carried.

Les threatened to quit, but Rex persuaded him to stay on, at least until after an upcoming style show in Austin. As Les rose to leave, according to his statement, he told Rex, “ ‘When you started all this stuff about Muscles I did not know what was coming down but now I do know’ . . . I told Rex that I had a lawyer and this lawyer had a letter detailing what had gone on and I told Rex just to be sure that nothing happened to me. Rex just looked at me . . .”

Two days after his meeting with Rex, Les cleaned out his desk at Cutter Bill’s and left the best job he had ever had. He was 49 years old and in trouble. Willis Butler could not have called him at a more vulnerable time. “He asked me if I wanted to make the boat trip to South America,” Les later stated. “I said yes.”

Stick ’Em Up

The Agnes Pauline was a handsome eighty-foot shrimper that had been outfitted with sonar, radar, and quite a lot of very expensive navigational equipment, all of which would break down during the voyage. After their first day out the crew started calling the ship the Aggie, as if that were the kind of joke she had turned out to be.

There were five on board, three men and two women. Les brought along Gloria Davis, a strapping cowgirl he had met on the horse circuit. A green-eyed blonde with an acid tongue, she loved Les, and that had been a tonic to his ego after his unsuccessful suicide attempt.

Gloria noticed right away that “the three super sailors with us didn’t know how to work the rigging on the shrimp boat. Oh, well,” she wrote in her diary, “I guess you can’t think of everything.” She and Holly, the other woman, set about arranging the galley while the men steered the ship out of Galveston Bay to the open sea. They soon got their first inkling of what the trip was going to be like. “The brooms we had hung on the wall were flopping around like plastic pennants in a strong wind,” Gloria wrote. “Doors were banging open and shut, the portable radio and miscellaneous items slid off the table, and then the biggie happened. The refrigerator door flew open and spit out 5 gallons of milk, a bottle of salad dressing, two bottles of orange juice, a jar of strawberry jam, and a can of 7-Up. . . .

“We finally got it all cleaned up and went upstairs to check on the guys. The first thing they asked me for was something to eat. Well, needless to say, my stomach wasn’t about to let me back down in the kitchen again. I looked at Holly and I knew she felt the same way. I headed for the nearest bed and I think she did too, after making a stop in the bathroom first.”

It took nine days to reach Colombia, through fifteen-foot seas and winds that reached thirty knots. Les was beleaguered by kidney-stone attacks, the pump broke down so often that it was almost impossible to shower, and it didn’t help that the Aggie started taking on water the moment she left port. The sonar unit had been installed upside down on the hull, and the water gushed in steadily. They had to pump bilge water constantly. It wasn’t altogether horrible, however. Gloria wrote that her first night at sea was “a terrific experience. The ocean was calm, the sky clear and the moon and stars looked as if they were sewn onto an endless black velvet canvas as a large pearl centered among a thousand tiny diamond chips.” She and Les stood watch together at the wheel, and they were so moved they hardly spoke.

The Aggie anchored off the Colombian coast in a gale, and in the middle of the night one of the men discovered that the anchor line was broken. They were drifting backward into the rocks in winds up to forty knots. There was nothing to do but steer straight into the face of the storm.

To make things worse, they couldn’t establish contact with Big Pete, their Colombian connection, for several days, so they just steamed along the coastline. Finally Big Pete sent word that delivery would be postponed another three days. “I think it’s our bad luck that keeps us going,” Gloria decided. “If we didn’t have bad luck we wouldn’t have any.”

At last the cargo was ready to be loaded. “The reality of this trip was finally starting to grip me,” wrote Gloria. “I sat perched atop the wheel house with my shotgun, two boxes of shells & a 38 revolver. It’s not the danger that bothered me, it was the way it was affecting Les. He was like a kid playing cops & robbers.” After midnight Big Pete’s boats arrived—elongated canoes with outboard motors. They pulled up on either side and started throwing bales of marijuana aboard. The loading wasn’t finished until nearly dawn, and everybody just about collapsed.

The return was easier; with all that ballast in the hold, the Aggie sat better in the water, although she was leaking faster than ever. Everyone was euphoric. They took pictures of each other posing on the marijuana bales, holding their weapons. Les looked tan and rugged aiming an automatic weapon into the sunset and wincing like the Marlboro Man. Right away he started talking about making another run.

They passed Thanksgiving on board and celebrated by charcoaling a seven-pound roast—“not very traditional but good,” Gloria decided. After dinner the guys were making plans, so Gloria took her coffee and went out onto the deck. The air felt nice and cool on her shoulders. “When there’s no moon out, it’s totally black outside. There’s no horizon, nothing to divide the sea from the sky. It’s almost like you’re weightless, floating through a black void.” She thought about Les, who was down in the cabin sketching out his new career, and it made her shiver to think of the risks involved. “If we were to get caught it would mean we would be separated for a long time. I don’t think I could handle that. I love him and need him so deeply, I couldn’t live without him. To me, nothing in this world is important enough to risk that. I guess I’m just feeling sorry for myself because he doesn’t feel the same way I do.”

Tempers got short when cigarette rationing began, and everyone was ready to be home by the time they finally made it back to Texas six days after Thanksgiving, 1978. They passed up Muscles’s invisible seafood company near High Island and steamed through Sabine Pass right up to the public docks in Port Arthur, where they had reserved a spot to unload their shipment. Once they left the open ocean, the smell that had trailed them all the way through the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico caught up with them. They passed right in front of the Coast Guard station and docked next to some other shrimpers that were gassing up at the docks, only two blocks from the county courthouse in downtown Port Arthur. “The odor of marijuana,” Les later confessed, “was tremendous.”

Of course they had been as good as caught, really, before they ever left port. The entire operation had been like a ripe fruit waiting to be plucked—and the pluckers had been pulling rank and fighting jurisdictional problems for the entire 22 days the Aggie was at sea. In the end everyone got in on the bust, which began as soon as Jamie Holland and Willis Butler and some of the cowhands arrived with tractor-trailers to unload the boat. A crew-cut fed leaped up and actually said, “Stick ’em up.” Agents popped up everywhere. Customs agents, Treasury agents, Drug Enforcement Administration agents, DPS narcs, and even the Galveston County sheriff, who was eighty miles outside his jurisdiction. Everybody but the courthouse stenographer and the Port Arthur police got credit for the bust, and the Port Arthur police chief afterward complained angrily about the lack of cooperation: “But I guess the state and federal authorities don’t really care.”

The cowboys read the scene at once: box canyon, surrounded on all sides, no way out. The agents scrambled on board and ordered the crew to lie face down on the deck. One of them walked over to Les Fuller and stuck a shotgun in his ear. “Okay, cowboy,” he said, “are you going to give us the big man in Denton?”

The Jabbering Cowboy

The twenty tons of pot taken out of the Aggie’s hold were quickly described as the largest amount of drugs ever seized in the Beaumont–Port Arthur area. In the usual escalation of real values into “street” values, the feds estimated the pot to be worth $24 million. The case fell within the province of the assistant U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Texas, an assertively clever man named David Baugh who is one of the few black prosecutors in the country.

In one of the trials that followed, much was made of David Baugh’s ambition—a charge that was no less true of the lawyer who made it—and there was in fact every reason to believe that David Baugh was on the verge of a great career. The only brake on his forward progress was his unfortunate location: Beaumont, a city that, while not free of sin, is also not graced with the juicy gangland felonies of Houston or the tony white-collar crimes committed in the skyscrapers of Dallas.

But a marijuana case—no matter how big—is not the most prized scalp for a prosecutor’s belt. Possession of marijuana is no longer a crime in eleven states, and mere possession is seldom prosecuted in federal courts unless intent to distribute is proved. The mixed national attitudes, reflected in the variety of laws and penalties from state to state, invite comparison with liquor prohibition, when the rumrunners of Thunder Road were performing a service that many a citizen appreciated. David Baugh himself had talked about having to surrender certain behaviors when he became a federal prosecutor, and he sometimes wore a gold marijuana leaf in his lapel.

Back in Denton an attorney named Bill Trantham got a call from Muscles Foster. Trantham—or the Tarantula, as he came to be called by the legion of lawyers involved in the case—is a tall, brown-haired man with an unruly moustache and a perpetually astonished expression. His office is only a few steps from the Western State Bank, where Rex’s office is, and as an attorney he had frequently performed legal services for Cauble Enterprises. “Some of the boys are in trouble,” Muscles informed him, and he got $20,000 to Trantham to bail them out. Trantham drove all night to Beaumont, and when he arrived he found the bail set at $1.6 million.

In the prosecutor’s office the happy realization had dawned that this case was far bigger than it had first seemed. The government set out to establish its bargaining position. Around the courthouse, reporters were casually informed that the kingpin of the operation was Les Fuller—the word “kingpin” in this case being like a tail in search of a donkey and the donkey who gets stuck with it gets the heaviest charge, that of continuing criminal enterprise. That term is used to cow defendants into becoming government witnesses. To say that Les Fuller was the kingpin was tantamount to saying that he was facing ten years to life in prison, with no possibility of parole. The desired effect—abject terror—was quickly achieved. Out on bond, the cowboys scurried to their lawyers (who had been carefully chosen by Trantham) to see what deals they could make. The Marlboro Man was the first to crack. Names and dates tumbled forth and subpoenas went out, bringing in Carlos Gerdes, Ray Hawkins, and finally John Ruppel. But Muscles Foster was nowhere to be found.

The name of Rex Cauble did not appear on the subpoenas. Instead, the government began the cautious process of grand jury investigations, as many as three at a time, that subpoenaed records from Rex’s bank and the sales of his horses and virtually all of his business enterprises—but not Rex himself. In Denton, Rex watched nervously as a parade of FBI agents dispatched by Baugh went in and out of his bank, and he got reports from newsmen of Baugh’s frequent references to his involvement in the case. Articles began appearing in papers around the state outlining the links between the smuggling operation and the Cauble empire—information that Rex believed could have come only from the prosecutor’s office. “I never had bad publicity in my life,” he complained. “That damn nigger wants to nail my hide to his wall!”

The Unsuccessful Self-sacrifice

In the early days of December Muscles called the Tarantula from Memphis to find out what had happened to the busted cowboys. Trantham advised him to stay where he was, and then flew all the way to Memphis to fetch him. Trantham claims that Muscles was crazy when he found him in Memphis, although government investigators said that Muscles’s insanity blossomed on the long ride home. That may be so. As they passed through Little Rock, Muscles began to discourse on the future of marijuana smuggling, which, he told Trantham, would be conducted mostly with submarines. He already had his eye on a Navy surplus model that he had heard was selling for only $1 million. In his mind Trantham pictured Muscles with his cowboy hat sideways on his head, peering through the periscope of his sub as he murked along the bottom of the Houston Ship Channel.

Doc Whaley checked Muscles into Arlington Neuropsychiatric Hospital. “He was bonkers,” Whaley explained. Nobody told the government where Muscles was, so the speculation around the federal building that Muscles had been “taken care of” became an article of belief.

But Muscles was too crazy to stay in the hospital. After he got into an argument with a nurse he checked himself out. He hid out in a trailer in Krum, a couple of miles west of Denton, and finally called Willis Butler. “Willis came out and we had a little talk,” Muscles recalls. “I said, ‘You boys have got yourselves in a hell of a mess, but you all got families and I ain’t got no ties. Since I got you all in this jam just put the blame on me. I’m gone.’ ”

Willis had already made plans for dealing with the government. During the next week he made a number of calls to Tennessee, pestering Jamie Holland and John Ruppel to repay the money he had spent to outfit the Agnes Pauline. It was the tapes Butler made of these conversations that provided the principal evidence against Ruppel. They also offered the strongest exculpatory evidence for Rex.

“You know who they think’s done it is R. C. Big Man down there,” Jamie Holland says on the tape.

“They are wrong,” Willis replies.

“Well, I know,” says Jamie, “but they are trying to get after him. See, they wanted him on a bunch of other things.”

Willis finally went to the government and agreed to testify, with the rest of the cowboys, that Muscles Foster was the kingpin. It was the hardest thing Willis had to do in his life, since Muscles was his closest friend. The week before the first trial was scheduled, Willis drove up to the Oklahoma border and rented a cabin in a state park. Like Muscles and Les Fuller before him, Willis had reached that dark moment when life was no longer separate from the void. He opened the oven door in the cabin’s kitchen and turned on the gas. Then he lay down on the bed and waited. Not being much of a cook, Willis failed to realize that the burners on the stove had a pilot light. Thirty minutes later there was a terrific explosion that shattered the windows and blew the roof off the cabin—awakening Willis from his slumberous voyage to eternity, leaving him shaken and nauseated but otherwise perfectly fit to testify.

Secret T-shirts

By the time the trial began, in September 1979, the government had indicted 29 people. Pretrial hearings in federal judge Joe Fisher’s formal marble-and-walnut courtroom were overwhelmed by a lawyer-mob that shoved the prosecution away from its traditional table and even spilled into the spectator section. After the negotiating and the plea bargaining, only 12 of those indicted chose to stand trial; the rest pleaded guilty or testified for the government or, like Muscles, had never been found.

“This is not a marijuana trial,” David Baugh told the jury, “this is a racketeering trial.” He outlined the scale of the smuggling operation, estimating that 172,000 pounds of grass worth $34 million had been brought into the country by the defendants between August 1976 and December 1978. Three men were charged with the kingpin count of continuing criminal enterprise: John Ruppel, Carlos Gerdes, and an Orange shipbuilder named Martin Sneed. Ray Hawkins, Jamie Holland, and seven others, including a Louisiana horse dealer and his brother, faced conspiracy charges. The government also charged Jamie Holland’s wife, Beth, with criminal knowledge.

While the government prosecuted the defendants, the defense prosecuted Rex Cauble. It was a strategy formulated by some of the best narcotics lawyers in the country. They pointed out that the main government witnesses were all Cauble employees who had driven trucks full of marijuana to Rex’s ranches around the state, where the loads were divided and distributed, and who frequently met to scheme in Rex’s stores or his Denton saloon or his Houston apartment. “Has it occurred to you,” the jury was asked by Gerry Goldstein, the most renowned marijuana lawyer in Texas, “that everyone in this case connected to Cauble is either cooperating with the government or missing?”

The witnesses wanted to pin the tail on Muscles (as Muscles had suggested), but the lawyers kept pointing them to Rex. Larry Dale Washington, one of the cowhands, testified that Rex had paid him $5000 that Muscles owed him and that Rex had said he would take it out of “Muscles’s money.” Two of the cowhands admitted on the stand that Rex had bailed them out of jail and pad for their attorneys. None of them, however, would testify that Rex’s involvement went further than a vague guilty knowledge of what was going on everywhere around him. “Why are Cauble employees putting innocent people into this?” asked Ray Hawkins’ lawyer, referring to his client. “To protect the general.”

It was not, in the end, a good defense. Although two of the defendants were acquitted by the jury and one of them, Ruppel, appealed on a mistrial, nine of the twelve were convicted. (Later Judge Fisher overturned the continuing criminal enterprise conviction against Sneed.) Beth Holland and the Louisiana horse dealer were acquitted and the jury failed to reach a verdict in the case of John Ruppel.

Sometime in the middle of the trial David Baugh received at his office a package wrapped in brown paper and bearing the return address of Thompson Seafood, High Island, Texas. Baugh opened it with great caution. Inside was a yellow T-shirt with a note from the Tarantula. Baugh’s guffaws rang through the halls of the federal building, and pretty soon federal agents and defense attorneys were trailing into the prosecutor’s office like a column of ants. Urgent orders were placed over the telephone, and in a few days yellow T-shirts were everywhere, but always worn discreetly under blouses or long-sleeved shirts and suit coats. Witnesses wore them on the stand. Defendants wore them inside the bar. Even a favored news reporter in the audience wore one. Occasionally someone would open a collar to show a wink of yellow, like a gesture of fraternity. Gerry Goldstein finally blew open the conspiracy by entering his shirt into evidence. The judge looked at it in bewilderment. On the front of the shirt was a picture of the Aggie loaded down with marijuana plants, sailing behind the state of Texas. Above and below it, in bold, black letters, were the words “Cowboy Mafia.”

A Million for Muscles

The government assumed that Muscles was dead; the unspoken (at least to reporters) corollary was that Rex had killed him. Carlos Gerdes and another conspirator had refused to testify before the grand jury that was still looking into the smuggling operation, and they were being held for contempt of court. “They’re afraid the same thing could happen to them that happened to Muscles Foster,” a federal narc explained.

But Muscles was not dead; he was alive and well and living in Bolivia. He had gone into the lead pipe business in Santa Cruz. Bolivia does not extradite people charged on drug offenses, so Muscles made no effort to disguise his identity. On the contrary, he went out of his way to let his American acquaintances know that he was a wanted man, since they might not wish to associate with him.

One day a couple of Bolivian policemen appeared grinning at his door and said they were interested in talking to him and would he mind going into town? Muscles got his hat. He already knew what was going on. They didn’t go to town; they went to the airport and flew across the country to La Paz, where an American narcotics agent was waiting for him. “I minded in a way, and in a way I didn’t mind,” Muscles said. It had been hard to get news in Santa Cruz, and until he was kidnapped Muscles had been worried that everyone had forgotten about him. All of his life he had wanted to be wanted and now he was. Really wanted.

On the flight to Miami he admitted to his abductor that he’d done all right in the smuggling game, but that it was the man he used to work for who had made all the profit. When Muscles landed in Miami he was astonished at his sudden celebrity. “I couldn’t believe it. Mafia! Racketeering! I couldn’t believe they’d think those things.” A federal magistrate set his bond at over $1 million—$1 million for Muscles Foster! At last he was being treated as if he really was what he had once boasted of being: the godfather.

If You’ve Got G. Brockett Irwin . . .

In Muscles’s absence, John Ruppel had been convicted in the marijuana case on several charges, including that of continuing criminal enterprise, but because David Baugh had not revealed the terms of a government deal with two of his witnesses, the new judge in the case, Robert Parker, granted Ruppel yet another trial, his third. In the second trial—Ruppel II, as it became known around the courthouse—the defense attorney had continued the strategy of prosecuting Rex, so that David Baugh was finally moved to tell the jury, “There is ample evidence to indict Mr. Cauble”—an astonishing statement to make in open court. The obvious conclusion, since Rex was still unindicted, was that there was not yet enough evidence to convict. In the minds of nearly all observers, Muscles Foster’s return would take care of that.

Now that Muscles was back, he would be tried with Ruppel, the aging millionaire. Since Muscles claimed to be a pauper, Judge Parker had to find an attorney to represent him. The previous defendants had been represented by the finest—and most expensive—lawyers in the nation, some of whose fees began at $100,000. Court-appointed attorneys usually receive $1000, and although a lawyer with an established practice will occasionally accept a court appointment, for the most part such chores are foisted upon either younger attorneys who need exposure or legal hacks who will go through the motions just to pick up a fee. Judge Parker wanted Muscles to be well represented in a courtroom that included David Baugh and Ruppel’s highly respected, extremely expensive counselor, Robert Ritchie. Parker let his mind wander over the list of possible attorneys, and perhaps he smiled when he remembered the Longview Pygmy.

In a way, the choice was an act of rehabilitation. G. Brockett “Jerry” Irwin, at the age of 34, was in a troubled phase of his career, though his debut on the courthouse scene had seemed to promise a new Percy Foreman or Racehorse Haynes. Jerry Irwin had already developed a modest reputation in East Texas for winning impossible cases when he took on the defense of Don Trull for aggravated kidnapping. Irwin is very blond, with fair skin that turns florid when he gets passionate, and at five three and a half he is an object of fascination to jurors—rather like a miniature horse that dances at the circus. Although Trull had confessed to the crime on videotape, by the end of his trial, Irwin had persuaded the jury that the person who had been kidnapped—the victim in the case—was so much more worthless than his client that they let Trull go.

Right after that triumph Irwin was hired to defend Billy Sol Estes on a barrage of charges ranging from mail fraud to income tax evasion. It was the perfect case to establish Irwin’s career: a big name and a remote chance of winning. His defense of Billy Sol was as brilliant in its way as the Trull case; it was essentially that Estes is such a liar that nothing he ever says can be used against him. The jury was almost convinced. They acquitted Billy Sol on eleven counts and then convicted him on two. After that, Irwin was no longer the invincible dwarf; he was the man who lost Billy Sol. So when he returned to his office one day and found a note from Judge Parker appointing him to defend Muscles Foster, he recognized it as both a charitable act and the best chance he might ever get to make his mark in Texas jurisprudence. It certainly was the most improbable case in his career.

Muscles’s sisters, who wanted to arrange for his defense, were skeptical of a court-appointed attorney; they demanded Racehorse Haynes. But Bill Trantham agreed to meet Irwin in Longview. “I found him on the top floor of the only tall building in Longview, surrounded by pictures of himself,” Trantham recalls. “I knew then I was dealing with a fully developed ego.” He drove back to Denton, convinced that Jerry Irwin was the best lawyer for the job. In the meantime, one of Muscle’s sisters had placed a call to Racehorse, who told her, “If you’ve got G. Brockett Irwin, you don’t need Racehorse Haynes.”

The Last of the Marlboro Man

David Baugh had reason to be cocky. Since the beginning of the case, twenty people had been convicted and only two acquitted (and both of those were small fry by any measure). It was his biggest case and he’d performed brilliantly. There remained only his latest trial before he delivered his masterstroke, which he had been promising for more than a year now: the indictment of Rex Cauble.

There was plenty of circumstantial evidence; in fact, the transcripts were overflowing with references to Rex’s involvement, elicited by the best defense lawyers Baugh had ever faced. His entire approach to Rex had been laborious accumulation of facts and details, which were certainly damning but not enough for a conviction. However, there were two men whose testimony he was certain would clinch the government’s case. One was Muscles; he would surely fall. He was charged with seven counts of racketeering and possession with intent to distribute, as well as continuing criminal enterprise. In every trial so far, the witnesses had pointed to Muscles as the kingpin, and they could hardly change their stories now. After Muscles was convicted he’d be facing ten years to life with no parole; he would have to either testify against Rex or expect to grow old and die in prison.

One witness was already in the bag. He had been strangely absent from all the previous trials, and yet of all the government witnesses he had wound up with one of the lightest sentences. The Marlboro Man was Baugh’s hole card. More than any other evidence, Les Fuller’s statement had linked Rex to the case. Baugh had not chosen to play the Les Fuller card in the previous trials because he hadn’t wanted to tip his hand to Rex, but now he called Fuller’s lawyer to set up a meeting with Les in Dallas. Rex Cauble had finally been subpoenaed to testify—by both the prosecution and the defense—and it might be the very best moment to spring the trap.

The lawyer tried to reach Les, but Gloria—now Gloria Fuller—told him that her husband had flown down to Port Isabel with some business friends. On its return the plane took off from Port Isabel with four men aboard: Les; Jim Geders, a Dallas flight instructor; Jim Cole, part owner with Geders of an air charter company; and Steve Ott, a young man who worked for Geders. All four of them were accomplished pilots. A storm front had passed over Waco, so when the plane failed to arrive in Dallas a search was begun over the pastureland between Waco and Austin. Nothing was found.

It was in Corpus Christi that a television newsman named Ron Fulton, listening to a radio scanner, overheard a Coast Guard transmission about a duffel bag that had been picked up in a shrimper’s net in the bay. “Charlie, Oscar, Lima, Echo,” said the Coast Guard radioman, reading the name on the duffel bag: Cole. It was the first indication that the plane had never reached Central Texas but had gone down shortly after takeoff in clear weather.

Three bodies came up rather quickly. From a rented helicopter, Cole’s son spotted his father’s body in Corpus Christi Bay near Portland, and then Geders washed up on the shore near the causeway. Ott was found by a shrimper off Port Aransas. But no Les.

No one except Gloria seemed to believe that Les was dead. The authorities were not even searching for his body. There seemed to be an assumption that Les had staged the crash to keep from testifying. Gloria vowed that she would not go back to Dallas without his body. After Ron Fulton broadcast an appeal for assistance on the evening news, a boat operator and an electronics expert volunteered to help her with the search. It took more than a week, but they finally found his body, bloated and partly eaten by crabs. Gloria identified it by the gold ID bracelet on his wrist. The rest of his jewelry, worth thousands of dollars, had been looted. The airplane is still missing.

Rex Takes the Fifth

David Baugh had been trumped—by fate or what?—but he still had Muscles. The Longview Pygmy developed two strategies for Muscles’s defense. The first was to acknowledge quite honestly that the case was hopeless and to make a deal with the government. Irwin went to Baugh before the trial and tried to negotiate a plea, but Baugh was making no bargains. The more leverage he had on Muscles the better, and life imprisonment was good leverage. The second strategy was the only defense available, considering all the government witnesses and Muscles’s own loose statements. That was to plead insanity.

Insanity is an old and reliable defense in murder cases, or assault, or any other kind of case involving a rash, ill-considered action. Given Muscles’s history of depression and hospitalization, he would be an easy candidate for acquittal in a case like that. But the government wasn’t charging Muscles with doing something crazy. It was charging him with doing something clever—running the biggest smuggling operation in Texas for three years and making an extraordinary amount of money from it. On its face the insanity defense seemed ludicrous. Certainly it had never been offered in a smuggling case.

The trial was moved to Marshall, where it began May 23, 1980, with the government’s presentation of the “criminal enterprise.” David Baugh outlined the case from the day the Monkey was purchased until the seizure of the Agnes Pauline. Sitting at the defense table were Muscles Foster, in a Bolivian shirt and blue jeans, and John Ruppel.

“My first impression of him was that he should be on the Supreme Court,” Muscles says of his codefendant, and in fact it was easy to imagine Ruppel as a kindly judge with white hair and black glasses, tapping his gavel in gentle reprimand if the spectators got out of line and nodding off when the testimony began to wander. In Gatlinburg, where Ruppel had retired, he was known as an openhanded philanthropist. He had donated land for the new animal shelter and was one of the major boosters of the Fraternal Order of Police. John’s wife, Margaret, was a sweet-looking woman with a white ponytail and a gravely wounded expression. Outside the courtroom the Ruppels seemed to be exactly the sort of couple you might expect to see flying off to Hawaii for their golden wedding anniversary. Ruppel’s every physical aspect, from the frank little smile he gave the jury when he first sat down, to the clean and nicely shaped nails of the fingers he held intertwined as if in prayer, denoted respectability. As the jury listened to Baugh’s description of the smuggling operation, it was hard to imagine that this well-barbered old fellow would have anything to do with that crumpled reprobate beside him, Muscles Foster.

Irwin began his opening statement with an attack on David Baugh, who was, he warned the jury, “possessed of great ambition.” His client was a “lame pawn,” not a kingpin; twice he had attempted suicide, and during his many trips to the hospital “on at least thirty-one occasions they electrocuted Mr. Foster’s brain a little at a time.” Muscles was not innocent, Irwin admitted, but he was not guilty by reason of insanity. “He will not roll his eyes and he will not drool,” but “he suffers from anxiety reaction; chronic, moderately severe obsessional personality with chronic depressive trends; recurrent reactive depressions with paranoid features; an underlying manic depressive problem, probably associated with a genetic basis; alcohol dependence if not addiction . . .” Muscles seemed to sink in his chair under the load of clinical terms. Finally, Irwin alerted the jury that “the ghost of Rex C. Cauble will float through this courtroom throughout the trial,” and he suggested that the prosecutor was out to get Cauble only because “success has catapulted him to some fame.” That was the first time any defense lawyer had spoken well of Rex Cauble.

It was not the ghost of Rex Cauble but the old man himself who took the stand as the first witness, his face so red that he seemed ready to explode but speaking in such a whisper that he was barely heard beyond the bar. Baugh approached this moment with special savor: the ultimate kingpin, to Baugh’s mind, was finally out in the open, in the flesh and on the stand. At that moment Baugh must have wished Les Fuller were alive and waiting in the wings. Baugh asked the witness his name.

“Rex Carmack Cauble,” he said in a low voice, staring in frozen fascination at the confident black prosecutor who had been his adversary and the object of his curses for a year and a half. Rex gave his age as 66 and his business as “investments.”

“Do you know Muscles Foster?” asked Baugh.

“I respectfully decline to answer because of my attorney’s instructions.” Rex was being represented by William Hundley, the Washington attorney who had defended Tongsun Park and former attorney general John Mitchell.

Judge Parker would not let him get away with that; if Rex wanted to take the Fifth he’d have to admit it. “Is the basis of your refusal to answer the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution?”

“Whether you are guilty or not guilty, you are afforded that right,” Rex responded grudgingly. He claimed afterward that taking the Fifth was the hardest thing he ever did in his life.

Then the government began the parade of cowhands, who repeated their previous testimony when Baugh questioned them. Irwin seldom bothered to counter the incriminating statements. Instead, he used the government witnesses as character references for the defense. It was maddening to Baugh. The cowhands told how stupid Muscles was when he bragged to women, and what he was like when the women ran off and he went to the hospital. They remembered how changed he was when he returned. “He would go to bed of a night and maybe not sleep thirty minutes,” one of them said, “and he’d be up a-walkin’, and be mumblin’, talkin’ to hisself, and if you was ridin’ along, why, he would kind of be chewin’ on his tongue or spittin’ like.” It was sad and sometimes funny, those images of Muscles on the end of the fishing pier trying to assemble seventeen rods, or driving all the way from Beaumont to Dallas to pick up a battery charger and then forgetting what he went for, or gambling in Las Vegas casinos in his silk shirt and old blue jeans.

From Baugh’s perspective, the case was wandering out of control. Dr. Littlejohn, the court-appointed psychiatrist, testified that the defendant Foster “lacked substantial capacity during the period of 1976 through 1978 both to appreciate the wrongfulness of his conduct and to conform his conduct to the requirements of the law.”

At this point, Baugh’s boss, U.S. attorney John Hannah, arrived from Tyler to take the reins. Hannah is a stony-faced man with the ace of spades tattooed on one hand. He had to break down Littlejohn’s testimony. Hannah began by saying, “Assume that Mr. Foster coordinated the trucks and drivers to transport marijuana. Could the jury use that as some evidence pointing toward his sanity?”

Littlejohn nodded. “If he was able to function in a supervisory capacity over others, make judgments about deliveries and assigning trucks and this type of thing—yes, it would certainly affect the way I felt about the way he functioned at that time.”

“And if he managed the activities of at least five people over a period of two years to smuggle marijuana,” Hannah continued, “that would be evidence of his sanity, would it not?”

“Yes, sir.”

“If he left the country and traveled to Bolivia to escape prosecution, that would be evidence of his sanity, would it not?”

“Well . . . if he left to escape prosecution that he knew was coming, yes . . .”

Hannah began to run down the list—“that he arranged offload sites . . . that he established a shrimp company using a fictitious name . . . that he took part in the importation of 172,000 pounds of marijuana in five shipments over a period of two years without being detected by law enforcement officers”—and if all those things were accepted as true (and they were not disputed), wouldn’t the jury have to accept the fact that Mr. Foster was sane? Littlejohn more or less agreed that they would. John Hannah placed his notes in his briefcase and returned to Tyler.

“When Hannah got through with Littlejohn, I didn’t see any way to salvage the case,” Irwin admits. During Ruppel’s defense Irwin sat at the table and seriously considered a plea bargain on any terms. He really had only two witnesses to call: Doc Whaley, who could add some history of Muscles’s mental problems, and Muscles’s sister Joanne Wells.

The Ruppels each took the stand; they seemed like nice folks, very normal. Ruppel’s defense was that he enjoyed helping youngsters get ahead in the world, but that some of them had obviously taken advantage of his charity and naiveté. It was a pretty Milquetoast defense compared to the Byzantine complications of Muscles’s mentality, which was on trial beside him.

Irwin decided to press on; he called his witnesses. Doc Whaley told of Muscles’s “great feelings of inadequacy, his misgivings about his personal appearance. He often spoke of how ugly he was and how he could never keep a woman because he was too unattractive.” Joanne Wells told the jury about her brother’s early life, the father who had died in a state hospital, another sister who is a paranoid schizophrenic. “Mr. Cauble took care of my brother,” she testified. “He not only saw to his dental work, he sent him to the eye doctor, he tried to make him eat properly. He saw to his clothing. He would go once a week and gather up his clothes and send them to the laundry.”

Joanne testified that after Muscles ran away because of Leslie Sprinkles, “Mr. Cauble sent people looking for him all over the state, and Mr. Cauble had to go to the hospital and Muscles heard about it. So he came home and I met him in Denton and we went out together. We were expecting a big confrontation with Mr. Cauble. Well! We walked in the door and Mr. Cauble’s face lit up like a Christmas tree. I’ve never seen anything like it. And Muscles said, ‘How are you, old man?’ and he said, ‘How do you think I could be with you running off all over the country?’ ”

In a way, it was a risk to draw out this love relationship between Muscles and Rex, but there it was, two men with as complex an emotional relationship as anyone could imagine, each fearfully dependent on the other in ways that psychiatrists had described but couldn’t explain. Irwin closed Joanne Wells’s testimony by asking what Muscles had talked about doing if he hadn’t gotten caught. She said he told her he had planned to go to Iran to free the hostages.

The jury retired at 4:30 p.m. on June 3, 1980, and they reached a verdict a few moments after midnight. Nice Mr. Ruppel was convicted on four counts, although he was acquitted of continuing criminal enterprise. Muscles Foster was found not guilty. Muscles nodded and looked around. He asked the marshal if he could say hello to his sisters, who were standing in the spectator section. He was so disoriented that the judge called him to the bench. “Mr. Foster, this verdict means you are a free man,” the judge explained. “You’re free to go.” Muscles thanked him and said he believed he’d gotten a fair trial. Then he turned around and walked outside.

He strolled out of the courthouse to where Jerry Irwin’s Buick was parked. Strange, to be suddenly out of jail and free of the courthouse, like any ordinary citizen on a summer night and unlike, well, the godfather of the Cowboy Mafia. Muscles waited for Irwin to unlock the door and then he sat and gazed at the stars through the sunroof. Finally Muscles looked at Irwin and said, “Now how in the hell did you do that?”

Inside the courthouse, David Baugh was asking the same question. Of the two witnesses he might have used to convict Rex Cauble, one was dead and the other—as far as the jury was concerned—was crazy. The entire foundation of his case had crumbled with Muscles’s acquittal. He would try to rebuild it, of course, but in the eighteen months he had been preparing to indict Rex, the odds favoring conviction had never seemed worse. Was it over? He couldn’t say. Was Rex guilty? He couldn’t prove it, not now at any rate, and he must be wondering if “not now” really means “not yet” or “not ever.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Marijuana

- Longreads

- Cowboys

- Denton