This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

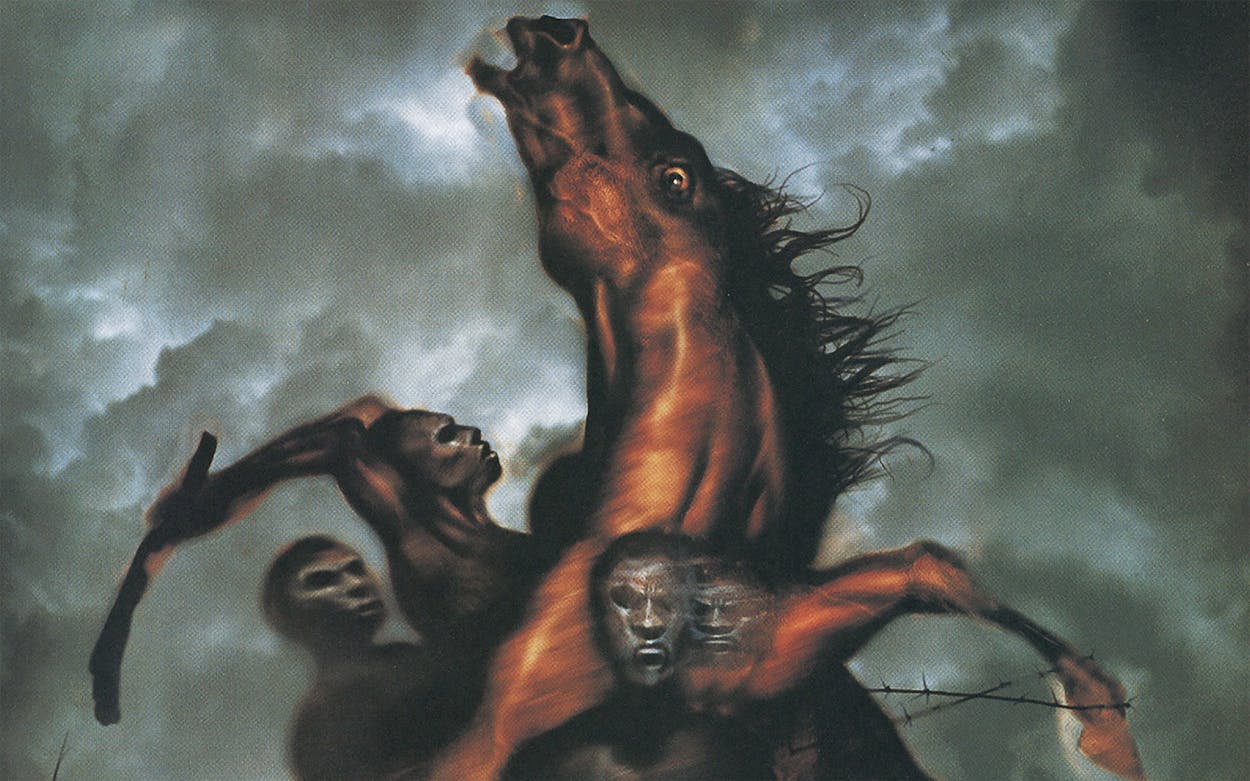

The horse was a fourteen-year-old sorrel gelding with a blaze face. As it lay there in the bloodstained meadow, with its right eye gone milky and its rear covered with gashes, the softness of its coat remained unmarred, its hindquarters still rippled, and above its sturdy back, its long mane hung in an insouciant tease. Its legs still suggested power and grace, war and play. Even beaten to death, the horse looked strangely indomitable.

Its registered name was Mister Wilson Boy, and in earlier years it had been a prizewinning cutting horse. Of late its knees had become arthritic, and so the horse had passed its final days in a ten-acre pasture just west of the East Texas town of Silsbee. Both the pasture and the horse were owned by Silsbee High School football coach Charlie Woodard, an even-tempered 53-year-old man who taught Sunday school at the First Methodist Church. Woodard was that rare Texas football coach who was more interested in the lives of the boys who played the game than in the game’s outcome. He loved children, and one way he showed this was by frequently letting them ride Mister Wilson Boy around his pasture. Woodard trusted his horse around children, and children around his horse—until the morning of Monday, September 18, 1995, when he was informed that the brutes who had clubbed his horse to death four days earlier were seven boys and one girl, ranging in age from eight to fourteen.

The revelation shocked and disturbed Coach Woodard—“It ruins my faith in humanity,” he told a friend. The owner’s reaction turned out to be the tamest on record. From all over America, letters seething with revulsion and vindictiveness poured in to the Hardin County courthouse: “What horrible children we are raising in this country.” “They are our future Mansons, Gacys, and other perverts. Do not allow them back into society.” “I believe any punishment you can give these monsters cannot be severe enough!” “I would suggest a public, bare-butt caning of them.” “Perhaps we should wrap them in barbed wire and beat them with sticks.” “Hang them and get it over with.” So hostile was the public sentiment, says Hardin County prosecutor David Sheffield, that “it put me, the prosecutor of the kids, in a position of wanting to defend them. We had to put up metal detectors in the courthouse halls. After reading all these letters about how the kids should be hanged or mutilated, we were worried that some nut was going to come down to Hardin County and take care of the horse problem himself.”

Improbably, the Silsbee horse-killing case became one of the most talked-about crime stories of 1995. Readers of the New York Times, the Washington Post, and newspapers in England and Australia were alerted to the macabre drama; Time magazine sent a reporter and a photographer to Silsbee; and Ann Landers waxed indignant in her column. In an age that finds us immunized from any horror we may inflict upon each other, the eight Silsbee youths may have committed one of the last outrages left to commit.

Why they did so was a matter lost in the stampede to punish them. What clues there are suggest a conclusion at odds with the prevailing belief that the horse killing was simply the grisly handiwork of eight Jeffrey Dahmers in the making. The perpetrators shared three elements: their town, which was Silsbee; their attitude toward authority, which (with one notable exception) was disrespectful; and their skin color, which was black. The Hardin County authorities never revealed that last fact to the press, perhaps fearing that the disclosure would only further inflame the public’s passions. Since then, however, two mothers whose four children have been sent to correctional facilities insist that the sentences were racially motivated. Few Silsbee residents want to believe that this is true, just as few wish to believe that the experience of being black in East Texas somehow set the stage for the children’s violent outburst in Coach Woodard’s pasture. Regardless, it is hard to deny that this peculiarly rural crime story harbors more than a few distinctly (and depressingly) urban elements. It is as if William Golding retold The Lord of the Flies using the characters from Boyz N the Hood and then set his hostile mob loose on Silsbee.

“When we heard about what happened to Charlie Woodard’s horse, I said, ‘I’ll bet I can tell you exactly who did it,’ ” a faculty member of Silsbee Middle School tells me. “Sure enough, I was right. They were the worst kids we had.”

Then she catches herself and says, “I take that back. Oliver was a big surprise. That one blew us all away.”

Oliver (whose name, as with the rest of the juveniles in this story, has been changed) grew up in Silsbee, a quiet East Texas town of lumber mills and churches less than twenty miles north of Beaumont. He grew up on the predominantly black west side, an area abutting the railroad tracks that no one would confuse with suburbia. Of the eight juveniles accused of killing Coach Woodard’s horse, none had it worse than Oliver. His mother had died in childbirth, and his father was addicted to crack. Oliver lived with his father and three siblings in a house that seems to be standing only as a monument to decay. Its roof is tattered, its front door is pocked with holes, and the walls appear to be on the verge of collapse. When Oliver’s father was sent to county jail on a drug possession charge a few years ago, the children moved in with their maternal grandmother a couple of miles away, in a one-room rural shack that appeared to lack running water, judging by the condition of the house and the smell of urine that accompanied the children to school.

“A baby got killed around here recently,” Darlene says, “and the next day everyone forgets about it. But every day we hear it: horse killing, horse killing.”

If any of the accused had a right to hate the world, it was Oliver, who wore soiled clothes and shoes that seemed to be rotting off of his feet and was teased even by the other black kids for being poor and malodorous. Yet Oliver won the hearts of the Silsbee teachers. He was shy and unfailingly polite—“You could tell he was raised by his grandma,” one of them says—and though he seldom had adequate school supplies, he was, as one teacher puts it, “a wonderful student. Half the time he never had socks, much less pencils and paper, but he still made A’s and B’s.” To avoid being teased by the others in the bus line, Oliver and his younger brother would sit in an art teacher’s classroom after school and draw pictures until the bus arrived.

One day in December, when Oliver’s father was in jail, a teacher asked Oliver what he hoped to get for Christmas. “Well,” the boy said with a rueful grin, “I’d like to get a bicycle. But I don’t think Santa will be bringing me anything.” The teacher was touched and contacted other faculty members. Pooling their money, the Silsbee faculty bought bicycles, underwear, and socks for Oliver and each of his three siblings.

Oliver did nothing to make the teachers regret their charity. But by the spring of 1995, it was becoming clear that the fourteen-year-old boy was having trouble keeping up with his schoolwork. Perhaps there was turmoil at home with the return of Oliver’s father; perhaps the relentless teasing, combined with the onset of adolescent hormones, had gotten the better of him. In any event, the Silsbee Middle School authorities believed they had no choice but to flunk Oliver and have him repeat the eighth grade. Thus stigmatized, Oliver returned to school in August 1995 and found himself in the company of new classmates—including Mason, Willie, and Sam, who along with Sam’s younger brother Doyle and Willie’s younger sister Charisse were the faculty’s consensus choice as some of the worst troublemakers at Silsbee Middle School.

The five had much in common. Like Oliver, they lacked reliable father figures, and their mothers worked for low wages—though each child was far better off than Oliver. All five of them had been given after-school tutoring; all five, wrote one administrator to the Hardin County authorities, “were hand-scheduled to make sure they had the teachers who we felt could give them the opportunities they needed.” Yet they were often disruptive in class, given to defying teachers’ orders, and consistently involved in hallway skirmishes with classmates. They bullied, stole change from other kids. Four of them had been placed on probation in the spring of 1995 for breaking into the school on one or two occasions, vandalizing the classrooms, and stealing money out of the vending machines.

Sam, the only one who didn’t participate in the burglaries, was a college scholarship-quality football player and the smartest of the group—“But also the meanest,” says one of the teachers. He was heard to address one black lawman with “Hey, boy” and once lunged at a teacher and had to be restrained in a headlock by the principal. Though county authorities couldn’t prove it, they believed that Sam had been involved in a drive-by shooting in 1994 and a related aggravated assault the following year—“The two most violent juvenile crimes we’d had till the horse incident,” says one official. Sam was more astute at covering his tracks than his twelve-year-old brother, Doyle, who in addition to the burglary had twice been shipped off to the authorities for disorderly conduct at school. Mason, a frequent runaway whose mother had long ago told probation officers, “I can’t control him, and I wish you’d send him somewhere,” was perhaps the most openly rebellious of the lot, while Willie saw more sport in bullying his smaller classmates. Willie and his twelve-year-old sister Charisse were inseparable, and the latter was every bit as hard-edged as the former. Charisse took her schoolwork more seriously than the rest until her wayward attention span or hot temper would inevitably do her in. “They were all scared of her—white kids, black kids, even the teachers,” says one faculty member.

The company that Oliver fell into was, by all accounts, unsupervised—“a pack of kids running around like a pack of dogs,” as one local law enforcement official puts it. They roamed the streets of Silsbee day and night. School sports would have been available to them had they not been thrown off the teams or kept from trying out because “their stubborn behavior and poor attitude made them impossible to work with,” according to one coach. When disciplined, several of them would claim that they were being singled out because of the color of their skin. In fact, most of the Silsbee teachers were white; then again, about 30 percent of the students were black and seemed to get along fine with the faculty. It dismayed faculty members to hear children so readily playing the race card.

Then again, a few of the veteran teachers had an insight into the matter. After all, they had taught the children’s mothers too.

“It was a racist thing, that’s what it was,” Joyce says as she disperses her cigarette smoke and stares furiously at the ground. “They’ve done ’em so wrong. Shackled down and all. Locked up like animals. The good Lord ain’t sleepin’, I’ll tell you that.”

“They come from good homes,” chimes in Darlene, her voice louder but less bitter than Joyce’s. “Good homes! Sometimes I pull double shifts trying to make ends meet. I don’t have no record. They try to make it sound like they was runnin’ wild.”

“Like we was drug addicts,” spits out Joyce. “Street women. You can’t watch any child seven and twenty-four. It ain’t like that. I felt like telling ’em, ‘Okay, just take me to jail, ’cause I was wrong. I wasn’t paying more attention.’ But we was working. Every last one of us was working. Working hard.”

There is a pridefulness about the woman that must be terrifying to some, including the waitress at the local Golden Corral who tiptoes up and asks if Joyce would like her glass refilled, a question Joyce sullenly answers in the affirmative only after it is asked three times. Her attractiveness is the hard kind, while Darlene is rounder and more genial. In the restaurant, everyone is staring at us. The two women are conspicuous in every way, and they are not apologizing, not for anything. Darlene and Joyce work together at a retirement home. They have known each other since childhood, during which time they cultivated fearsome reputations. (“Darlene would meet you at the candy machine, and if you didn’t give her your change, she’d whup you,” remembers one former classmate. “And Joyce was just as mean as a snake.”) Though they have little good to say in return about their birthplace—“Hardin County: Hard On Blacks” is their summation—they have remained in Silsbee, as if daring the city to make the first move. In the meantime, they have raised their children to wear chips on their shoulders as they have, to grow up in a posture of resentment, and to obey a singular commandment: “Thou shalt not respect any white authority figure.” Today, each woman has two children in state correctional facilities, all four having been punished for their role in the killing of Coach Woodard’s horse.

“When they sent Sam off, they made him get down on his knees and they shackled him,” Joyce remembers in her low, venomous voice.

“And my Charisse—when I go visit her in that reform school, they bring her out in shackles,” moans Darlene. “They got her in a place where they don’t let her see sunlight or nothin’. And if they get bad, they get strapped down to a chair. I told her, ‘Girl, behave, you do what you have to do. But don’t you let them strap you down to no chair.’ ”

“Jesus ain’t sleepin’,” murmurs Joyce.

“Now, my boy Willie owned up to what he did,” Darlene says. “He said that he hit that horse one or two times.”

“They were chunking sticks at it,” nods Joyce. “But the horse was still alive when they left. Those children did not beat that horse to death.”

One of the more embarrassing elements of the mothers’ shared sense of victimization is that they promote this classic child’s lie—namely, that a second group of children actually arrived on the scene and killed the horse after their own children had vacated the premises. Repeatedly the two women undercut their own credibility: criticizing the media for sensationalizing the horse-killing case and then asking me if I intend to pay for this interview; extolling their sense of parental responsibility and then falsely claiming that they are meeting the court-ordered restitution payments for the horse’s death; and generally refusing to acknowledge that their children are somewhat less than angelic.

All the same, there is something inherently sympathetic about their predicament. It has been all too easy to criticize the mothers, all too easy to forget the fathers who long ago abandoned the household. No thanks to the fathers, the women are not welfare mothers; they do not have arrest records. There is little doubt that they truly believe they are doing the best job possible of raising their children. In fact, Joyce offers me a challenge: “You come to our houses, and you tell me if we live like street trash.” And after we hop into the car and drive to her apartment, I find that she is right: It is neat and modestly fashionable—and Darlene’s house, though forbidding in appearance from the outside, is warmly cluttered with pictures of her two incarcerated children.

The public response to their children’s crime has staggered the two mothers. Men and women they grew up with have written to the Silsbee Bee, suggesting that the children be neutered or beaten to death. People they have never met, from all over the world, have labeled their children monsters. After Joyce, in the heat of indignation upon her children’s arrest, made the unfortunate remark to a reporter that “if they’re gonna make me pay restitution for that horse, I better get some of that meat in my freezer,” one student told her that a schoolteacher had remarked to her class, “They ought to give her the meat with maggots in it.” A schoolteacher! “People get shot every day,” Darlene says with a sigh. “A baby got killed around here recently, and the next day everyone forgets about it. But every day we hear it: horse killing, horse killing.” It wasn’t teenage white kids in nearby Lumberton selling crack on schoolyards, it wasn’t a drive-by shooting in Kountze—it wasn’t those less-publicized crimes, it was an animal, only an animal, and after all, it was still alive when their children left . . .

And besides, there is the pool. Among whites and blacks alike, it is acknowledged that the Silsbee Swim Club, located on the northeast edge of town, continues to discourage black children from using the only “public” pool in town. Compared with most small East Texas towns, Silsbee has always struck me as a harmonious and inviting place; no one could put it in the same league as its Klan-friendly neighbor, Vidor. But it is easy to see how blacks in Silsbee have viewed the pool as an ugly reminder that there will always be two distinct classes, one with privileges withheld from the other.

“I’m gonna show you where our children swim,” Joyce says as we drive. She directs me toward a battered old mulecart dirt road that zigzags its way until it dead-ends in the middle of a pine thicket. Directly below us is a fast-moving, malt-colored slough. It is of indeterminable depth, and one can only imagine what lurks beneath the surface. We glumly stare at the creek in silence for a while. Then Joyce says, “A little girl came and told us our children was swimming in here. We come over here and we yell at ’em, ‘Y’all get out of that ol’ nasty water right now!’ ”

“We whupped ’em right there on the spot,” remembers Darlene.

A friend of the women who has accompanied us begins to shiver. “They never should’ve been out here,” she murmurs.

“That’s right,” Joyce says. “They never should’ve. But they got nowhere else to go.”

Apparently it all began with the children swimming in Coach Woodard’s stock tank. They had discovered the tank while following a trail that led from the projects into the Piney Woods. After a mile or so, the trail emptied out to a pasture surrounded by barbed wire. A mile and a fence were nothing for bored kids looking to stay cool on summer afternoons. There was too much heat, and too much time to kill—beginning in May, when Willie, Charisse, Doyle, and Mason were all suspended through the end of the semester following the second burglary of Silsbee Middle School.

Now it was a new semester, though it was starting pretty much as the last one had ended. On Wednesday, September 13, Doyle was hauled into the principal’s office. Someone had spray-painted the word “Doyle” on the kindergarten walls. There was only one Doyle in the school system. “Why did you do it?” an administrator asked him.

He shrugged. “I thought it would be fun,” he said. Then he added, “I just didn’t have nothing to do.”

It had been that kind of day, and not just for Doyle. His big brother Sam, along with the chronic runaway Mason, had been disruptive in school and were now spending their daytime hours in detention cubicles at the Student Alternative Center, adjacent to the high school. Getting lectured at, hunched in a little space all day long like a dog at a kennel—on days like this one, they had to get out. They had to hit the trail.

When they got to the pasture, two cows and a calf were standing by the tank. Suddenly no one was thinking about swimming. They advanced on the cattle. The dumb animals skittered away. The kids began to chase them, around and around the pasture, laughing at the cattle, throwing sticks at them. In a panic, the cattle rammed through a rickety wooden gate and fled to another area of the property. The kids agreed that the whole episode was rather thrilling. They resolved to come back the next day.

Eight of them did. Accompanying Willie, Charisse, Sam, Doyle, Mason, and their new classmate Oliver were two brothers, Tory and Horace, who were eight and nine respectively but already well on their way to establishing themselves as classroom scourges. A ninth boy, Maurice, had chased the cattle with them the previous day but was grounded by his parents that day after his progress report arrived in the mail. He would miss out on the fun.

Along the trail they happened upon two other boys, who were walking their dogs. “We’re going to the pasture to chase some cattle around,” someone explained. Why not, said the two boys. And so a throng consisting of nine boys, one girl, and two dogs followed the trail, crawled under the barbed wire, and roamed around the pasture, searching for the cattle until they saw, instead, the horse.

It stood alone, grazing in the meadow, about 150 yards away from the barn where it spent its nights. Only an hour or so earlier, at five in the afternoon, Coach Woodard had paid it his daily after-school visit. Now it stared at ten young strangers. They were not here to feed it, or to ride it. Still, they were coming its way. Mister Wilson Boy began to run.

They gave chase. The horse galloped around the pasture several times with Willie, Sam, Doyle, Mason, Oliver, Tory, and Horace on its heels. The meadow was littered with oak limbs ranging from one to two feet long and one to two inches wide. The boys began to pick up the sticks and hurl them at the horse. Tory, the eight-year-old, found a glass bottle and flung it, but the horse was too fast. The others, however, were hitting their mark. Charisse tossed one stick, missed, and then began scrambling around the meadow, gathering sticks for the boys.

Suddenly they had the horse backed up against the fence. The boys closed in. The horse tried to pivot away, and one of its hind legs became entangled in the barbed wire. Sam, Doyle, Willie, Mason, and the nine-year-old boy, Horace, began to flail away at the horse, hitting it repeatedly in the backside, ribs, belly, and neck. Then, from shock or a well-aimed throw, the animal fell hard to the ground.

The boys descended upon it and went to work on its head while the horse lay defenseless. The two boys with the dogs had seen enough. They retreated to the woods as the others jeered at them.

When the horse was no longer moving, one of the boys took a stick and rammed it hard up the animal’s nostril. Their blood-stained weapons were strewn around the horse. The children looked around. It was still daylight. To round off the afternoon, they broke into Coach Woodard’s toolshed, stole a few ropes, a machete, and a few cans of spray paint, threw a Weed Eater into the stock tank, and started the tractor engine—which was still running at seven o’clock Friday morning, when Coach Woodard visited the pasture to pay his ritual morning visit to Mister Wilson Boy.

On Monday, September 18, one of the two boys who had retreated from the pasture showed up at school crying. He wouldn’t say why he was upset. But across town, in the Student Alternative Center, Mason put the finishing touches on a sketch he had been making of a demon figure, scrawled “Lord of Pain” above it, and then leaned over to the boy in the adjacent detention cubicle. “Me and Sam and Doyle was the ones that killed the horse,” he whispered.

The horse killing had been the talk of Silsbee all weekend long, but the perpetrators were thought to be gang members from Kountze or perhaps some satanic cult—until Mason opened his mouth. The listener told what he had heard to Hardin County deputy sheriff Thomas Tyler, a hefty and amiable black man who had lived in west Silsbee his entire life. Tyler plucked Doyle from class that morning. The twelve-year-old boy gave the deputy the names of all the children who had been out at the pasture.

That Monday evening, the mothers of the perpetrators took their children to Tyler’s house and conferred in the deputy’s garage. He knew all of them—was kin, in fact, to more than one. The mothers were upset, the children less so as they recounted the episode. They didn’t know it was Coach Woodard’s farm. They hadn’t tried to kill the horse. They were just playing around, and one thing led to another. The horse, they insisted, still looked alive when they last saw it.

The parents offered to pool what money they had to give Coach Woodard. Several pledged to give their kids a whipping. When they had run out of things to say, the deputy weighed the situation. “Well,” he said, “I’ll do all I can to help. We’ve got to bring ’em all in to the juvenile office tomorrow—there’s no way around that. At the very least, I’ll try to see to it that they don’t punish the girl since she didn’t hit the horse.”

On Tuesday morning, the ten children who had been out at the pasture were taken by their mothers to the Hardin County courthouse. With their mothers present, deputy sheriff Darrell Werner questioned the children individually. By Werner’s questions, the ten suspects could apparently tell that the crimes, in increasing order of severity, seemed to be: chasing the horse, throwing things at the horse, hitting the horse while it was standing, hitting the horse while it was on the ground, and, worst of all, causing the horse to fall to the ground. Several of the children adjusted their stories accordingly. When asked, “Who knocked the horse to the ground?” four of them replied, “Oliver.”

Deputy Werner also wanted to know who the leader of the mob was. Several of them said, “Oliver.”

Oliver told Werner that none of this was true. All he did, according to his written confession, “was just chase the horse. I did not hit the horse or take anything from the property.” Werner didn’t believe him. Too many of the others had fingered him as the ringleader.

While each suspect was being questioned, the other children sat outside in the courthouse hallway with their parents. One building employee stepped out of her office and saw two children on their knees in front of a vending machine, reaching up into its guts, and pulling out bars of candy, the mothers sitting obliviously nearby.

The children were released to their parents. But angry callers had already begun telephoning the courthouse. At the same time, Silsbee faculty members and administrators confronted the Hardin County authorities. Why were these brutes being allowed to go back to school, and back to the streets of Silsbee? What kind of message did this send to the other students? Kill a horse, and see you at school tomorrow!

Less than 24 hours after their release, state district judge Bill Beggs ordered Willie, Charisse, Sam, Doyle, Mason, and Oliver held without bail until the conclusion of their hearings (the eight- and nine-year-old boys were too young to be removed from their parents, and the two boys with the dogs were exonerated). Beggs would later explain, “I considered a number of factors, including the safety of the community and the safety of the children involved.” But Beggs, who had been appointed to fill the vacated 88th District post, was doubtlessly considering politics too. An unelected Republican judge who ignored the outcries of angry white community leaders and let black hoodlums roam the streets of Silsbee would feel the voters’ wrath in the 1996 election.

And so the horse killers were again rounded up, driven away from school in marked vehicles, and imprisoned on the third floor of the Hardin County courthouse, in the cramped juvenile detention center. Extra mattresses were dragged in and tossed on the floor of the three-bedroom cell to accommodate the overflow—which was eased somewhat when Oliver and Mason were caught brawling in the cell and were subsequently shipped off to a juvenile center in Conroe.

The severity of their predicament took a while to sink in. Three or four days into their detention, the children were carrying on so loudly that a probation officer was moved to strip the center of all of its televisions, games, and furniture. The atmosphere became less festive after that, but it still did not exactly resemble a prayer-group meeting. Juvenile probation officer Ed Dickens, who had seen more than his share of miscreants during his five years of service at the Hardin County office, became disgusted with the seeming nonchalance of the horse killers. “Don’t any of you have so much as an ounce of remorse for what you did?” he demanded during a visit. Not one of them volunteered a show of contrition. Later, however, they penned notes of apology to Coach Woodard. Through visitors, they learned what was being said about them outside the courthouse. They began to ask Dickens questions about what reform school was like.

On October 5, after two weeks in custody, Willie and Mason were brought before Judge Beggs. Both of the fourteen-year-old boys were already on probation for breaking into Silsbee Middle School, which qualified them for a minimum three-year sentence at a Texas Youth Commission (TYC) correctional facility for juveniles. But because the TYC accepts only so many juveniles from each county, Beggs gave Willie a lighter sentence: six months at a private boot camp facility in Cotulla. With a rap of the gavel, two men in fatigues stepped forward and fitted the boy with shackles.

Mason, whose record included several runaway incidents as well as a citation for “making terroristic threats” and whose confession of the horse killing seemed far less believable than the others’, was sent off to a TYC facility along with Doyle. Doyle’s big brother Sam was sentenced to the Cotulla boot camp. Despite his repeated denial of wrongdoing, Oliver was sentenced to Cotulla as well.

On October 13, Charisse stood before Judge Beggs in the quiet courtroom, while just outside, a throng of TV cameramen and reporters angled for position. The twelve-year-old girl had not been implicated by the others in the actual beating of the horse. On the other hand, no boot camp facilities existed for girls, and Beggs did not wish to consider a lighter alternative, such as a wilderness camp. The judge ordered her to be sent to a TYC correctional institution two hundred miles away. For the first time since the horse killing a month earlier, Charisse broke down into loud, almost terrifying sobs.

Before the children were led away, investigating deputy Darrell Werner made a point of shaking each one’s hand. “Best of luck to you,” he told them.

They will need plenty of it. All six will return home this year, as the TYC needs the bed space for incoming juveniles and Hardin County cannot afford more than five months’ worth of the $237 daily fee charged by the Cotulla boot camp to house Willie, Sam, and Oliver. They will return to a world that considers them sick and twisted, and to a community that deeply resents the negative attention that the juveniles have drawn to Silsbee. It is an open question whether the six children will have learned anything—or, for that matter, whether learning anything will do them any good. For although the boot camps in particular are designed to teach respect for authority and to rehabilitate self-esteem, the lessons do not wear well in the precarious environment that helped spawn the crime to begin with. “It’s hard to come home and say no to your peers,” says Ed Dickens, the probation officer for the six. “And if the parent doesn’t grasp the seriousness of the matter, how can we expect the kid to?”

He manages a rueful smile from behind his desk at the county juvenile probation office and adds, “No, if experience holds true, we’ll see them back here again.”

But for what it is worth, the six are doing well—particularly Oliver, who is a squad leader at the Cotulla boot camp and has been chosen to march with the honor guard at a Texas A&M function. We can hope that the children will somehow beat the odds and somehow give this story a happy ending. For now, the following will have to do:

Throughout the shrill ordeal, Coach Woodard maintained a low profile. Unlike the Silsbee school officials, he made a point of not attending the trials or giving interviews. (“It’s best for the community that I not say anything,” he politely told me.) Letters of sympathy poured in from all over. Some of the envelopes contained checks to help buy the coach a replacement for Mister Wilson Boy, whose monetary value had been set by authorities at $10,000—though Woodard could easily have pressed for more, had he so chosen. The checks totaled somewhere in the neighborhood of $20,000; one check was written for $7,000. Coach Woodard sent each check back with a thank-you note. He wasn’t looking for charity—even though only one of the four families had made any of the $49.41-per-child monthly restitution payments. Besides, things had a way of working out. A friend named Jane Hill phoned the coach one day and said she had a four-year-old gelding that wasn’t getting much attention. How about if the coach kept the horse out at his pasture?

Coach Woodard looked embarrassed, but a little eager as well. “Well, Jane,” he stammered, “how long do you want me to keep him?”

“Just as long as you want,” she assured him.

A more troubling question came to mind. “But what if something were to happen to him out at my place?” he asked.

Take the horse, she urged him. And he did. The coach called the horse Jane, after its original owner. It was a sorrel with a blaze face.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Horses

- East Texas