This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

They probably first saw each other at a cross-country meet in the early autumn of 1995—two high school girls from neighboring small towns, competing in the two-mile run. There is no evidence that they said hello. Nor did they shake hands, as athletes sometimes do before the start of a race. Why should they have? It is doubtful the two girls even knew one another’s names. Adrianne Jones was a clear-complexioned, sun-kissed blonde, the kind of girl one boy described as “not just good looking, but I mean, good lookin’.” Diane Zamora, thinner and not as tall, was mesmerizing in a different way—her hair a dark circle around her face, her eyes dark as well, her eyebrows like slim shadows against her skin. “When she looked at you,” another boy would later say, “it was hard for you to stop staring back.”

There was no reason for the two to imagine that they had anything in common beyond cross-country. They were just pretty young teenagers in the full bloom of youth. What Adrianne and Diane did not know about each other, however, was that they were both drawn to the same boy—a lean, muscular high school senior named David Graham, who was described as “the perfect guy” by one classmate and “a brilliant student” by another. David was the kind of young man any parent would admire. He made straight A’s. He said “yes, sir” and “yes, ma’am” when talking to adults. “His life was so unblemished,” said one woman who knew him, “that he didn’t so much as throw a spitwad in school.”

At the time, David had chosen to be with Diane, who was called “the disciplined one” of the family by her mother because she would start studying for school before six o’clock each weekday morning. But David could not deny that there was something intriguing, and somewhat seductive, about Adrianne, who was called “bubble butt” by her mother because her bottom moved in sexy little circles when she walked. He found himself spending more time with her, talking to her, staring at her hazel eyes.

The two girls lined up for the cross-country race, waiting for the starter’s gun. It would not be long before they would meet again.

I thought long and hard about how to carry out the crime. I was stupid, but I was in love.

—From the killer’s confession

In the early morning hours of December 3, 1995, a farmer driving along a desolate country road saw the body of a teenage girl on the ground behind a barbed-wire fence. At first, he thought he was looking at road kill. The girl’s face was nearly unrecognizable. One bullet hole was in her left cheek, another in her forehead. She had been hit so hard on the left side of her head that the part of the skull above her ear was caved in like a pumpkin. She was wearing flannel shorts and a gray T-shirt that read, “UIL Region I Cross Country Regionals 1995.” Within hours, police officers identified her as Adrianne Jones, a sixteen-year-old high school sophomore from the town of Mansfield, southeast of Fort Worth.

A former farming community built around a grain elevator, home to an old indoor rodeo arena and some cheery antique stores along Main Street, Mansfield was one of the last places in the Dallas–Fort Worth corridor that still felt like a small town. In 1984, looking for a safe place to raise his family, Bill Jones moved his wife, Linda, and his three children—Adrianne and two younger brothers—to Mansfield from the Dallas area. He found a modest neighborhood where the homes were clustered together, the yards were like little green squares, and the echoey sound of children at play drifted down the streets. Jones, who made his living repairing heavy construction equipment, was a no-nonsense, bearded man who kept his heavy brown work boots on when he arrived home at the end of the day, wearing them even when he sat in his easy chair. He also was determined to keep a tight rein on his children—especially Adrianne, who was known as AJ. “I truly felt that if we had some rules that kept her away from teenage temptations,” Jones said, “we’d be okay.” It was only that autumn that he had allowed Adrianne to stay out past nine o’clock on weekends. If she told him she was going to a movie or to Six Flags Over Texas in nearby Arlington with friends, he would often make her produce a ticket stub when she came home to prove where she had been. He had nailed her bedroom windows shut so she couldn’t sneak out of the house at night.

It could hardly be said that Adrianne was a rebel. She took advanced honors courses, studied at least two hours a night, and was a good athlete. After she hurt her knee playing for the girls soccer team, she decided to join the girls’ cross-country team to get in better shape, and she became so good in the two-mile run that she helped the team qualify for the November regional meet in Lubbock. “Her school spirit was just so awesome,” said Carla Hays, an editor for the school newspaper, the Mansfield Uproar, bestowing upon Adrianne one of the greatest compliments a high school girl could receive. “I could see her becoming a cheerleader someday.” She also managed to work twenty hours a week at Golden Fried Chicken, a local fast-food restaurant. “She was my superstar employee,” said the restaurant’s manager, Tina Dollar. “I made her the cashier at the drive-through window because she knew how to put a smile on everyone’s face. She wore a hat with a smiley face drawn on the visor, and after taking an order, she’d say funny things to the customers like, ‘Okay, drive forward to the ninety-ninth window to get your food!’ ”

Adrianne thrived on attention, especially when it came from the teenage boys around town. One of Adrianne’s closest friends, Tracy Bumpass, called her “a big flirt.” Linda Jones, a chatty blonde who worked during the day as a massage therapist in a Mansfield hair salon, said her daughter would spend two hours putting on makeup just to make it look like she wasn’t wearing any: “When I asked her why she went to such trouble to put her makeup on before she went out of the house, she said, ‘Mom, you never know who you might meet.’ ”

And there were plenty of high school guys who wanted to meet her. They’d slowly cruise by the Joneses’ house. A few of the courageous ones would pull into the driveway to talk to Adrianne, who would be waiting for them in the front yard, casting quick glances toward the front door to see if her father was watching them. “I’m sure lots of guys really liked Adrianne,” said Sydney Jones, a friend and former soccer teammate. “She was the kind of girl who would say hi to you in the hallway at school even if you didn’t know her.”

It was precisely Adrianne’s popularity that was going to make the investigation into her murder so difficult. (Because Adrianne’s body had been found in the outskirts of the Dallas suburb Grand Prairie, detectives from that city’s police department—Dennis Clay and Dennis Meyer—and their boss, deputy police chief Brad Geary, were put in charge of the case.) Adults who are murdered rarely have more than a couple of dozen people close to them. But a high school student crosses paths with hundreds of other students every day. And it quickly became clear to the detectives that Adrianne knew her killer, or killers. There was no sign at the crime scene that she had struggled. There were no marks that her hands or legs had been restrained. Nor was there any indication that someone had broken into her house or had gone through her window to abduct her. Furthermore, an autopsy found no evidence that Adrianne had been sexually assaulted, which meant that this was not the act of a rapist. Adrianne’s death, the cops realized, was more like an execution, the result of some colossal fury. As one investigator would later say, “It takes a cold-blooded person to shoot a pretty young girl in the face from two to four feet away. That girl was mangled, and it was sickening to look at.”

Never did I imagine the heartache it would cause my school, my friends, Adrianne’s family, or even my community.

It was a story that would eventually send shock waves across the entire country: a terrifying, macabre tale that would have people everywhere asking what had happened to the best and brightest of America’s youth. At the start, however, Adrianne Jones’s murder was just another killing in a small town. Because so much local media attention was then focused on the kidnapping and brutal murder of a little girl named Amber Hagerman in Arlington, Adrianne’s death barely made the front pages of the Dallas and Fort Worth newspapers. In a society long accustomed to drive-by shootings and metal detectors at school entrances, dead teenagers didn’t warrant the press that they once did.

But within Mansfield itself, the news had residents reeling. High school administrators set up special rooms for students to meet with counselors. A tree was planted in memory of Adrianne next to the junior varsity soccer field, and more than 150 of her classmates joined hands around the tree and shouted, “Unity! Strength! Courage!” Some residents wore ribbons in her memory, and a small cross made from two branches wrapped with red electrical wire was placed where her body had been discovered. After the family held a private funeral for Adrianne at the Methodist church, Linda Jones agreed to allow the cross-country and soccer teams to come to the church for a second memorial service. On the altar was a glamorous color photo of Adrianne, taken a few weeks earlier, that Linda had planned to give her for Christmas. “Try to remember the good things about Adrianne,” she said in a spontaneous eulogy, trying to bolster the spirits of the students. “Do you remember the way she walked with that bubble butt of hers?”

Nearly crazed with grief, Linda consulted psychics to try to find out what had happened to Adrianne. She made sure to wear some item of her daughter’s almost every day—either a piece of clothing or her shoes or her makeup. At night, she and Bill left the light on in Adrianne’s bedroom, as if hoping their daughter would find her way back home. Kids drove past the house, staring through the open curtains, able to see Adrianne’s vanity, where she had put on her makeup, her stereo, and her bookcase, which still held a couple of her Stephen King novels.

Among the nearly 2,500 students at Mansfield High, it didn’t take long for the rumors to start flying. “A lot of us had this weird feeling that the killer was walking the halls with us,” said April Grossman, a friend of Adrianne’s who also ran cross-country and played on the soccer team. “Those of us who were really close to Adrianne were scared because we thought she might have been killed because of something she knew. And we thought, ‘Well, will the killer come after us thinking that Adrianne had told us the secret?’ ”

Some kids said they had heard that Adrianne used to slip out of the house to attend all-night “rave” parties as far away as Denton (an hour’s drive north of Mansfield). Maybe, they whispered, someone she met at a rave had wanted to kill her. Others said they had heard that she knew drug dealers. There was so much gossip about the boys Adrianne had been with that Linda went so far as to tell one reporter that her daughter was no “sleep-around.” There was even a preposterous story that a close girlfriend of Adrianne’s had wanted to kill her because Adrianne had told that girl’s mother about her getting drunk at a party. “About the only thing we didn’t hear,” Bill said, “was that Adrianne had been abducted by aliens.”

Still, for the investigators in the case—who had come to include the Mansfield police, a Texas Ranger, and extra Grand Prairie detectives—Adrianne’s murder had all the makings of a high school whodunit. Although the Texas Education Agency had named Mansfield High a mentor school (a distinction given only to the best high schools in the state), the teenagers there were like teenagers anywhere, their lives often driven by insecurities, inchoate yearnings, and a provincial restlessness. Wavering in that territory that lies between childhood and adulthood, the students tried on and discarded different selves as quickly as they went through blue jeans, always searching for the perfect fit. It was here that they confronted raw new emotions, like their own budding sexuality, and here that they first attempted to make their way through such moral dilemmas as whether to “do it” or not.

Sitting outside the high school in their unmarked cars, watching students troop in and out, the detectives prepared themselves to enter the humid realm of adolescence. They talked to school officials about the students who had a knack for minor trouble. They asked other kids if they knew anyone who was jealous of or angry at Adrianne. Within days, they had compiled a long list of kids they wanted to talk to.

Bill and Linda Jones had told the police that on the night of Adrianne’s death, they had reluctantly allowed her to talk on the phone past her usual ten o’clock cut-off time. Her new boyfriend, Tracy Smith, had been out of town that weekend with his parents, and he didn’t call until ten-thirty. Bill and Linda didn’t know Tracy that well. He was a large kid who was built like a lineman on a college football team, and he went to high school in the nearby town of Venus. Apparently, he and Adrianne had met just a couple of months earlier at the Golden Fried Chicken. Bill told Adrianne she could talk to Tracy but only for a few minutes.

During that call, Linda heard her daughter say, “Hold on, there’s someone on the other line.” Adrianne punched the call-waiting button and spoke quietly for a minute, then clicked back over and finished her conversation with Tracy.

“Who was that who called in?” Linda later asked.

According to Linda, Adrianne replied, “Oh, that was David from cross-country, and he’s upset about something.”

After talking with Tracy, Adrianne went to her room. At ten forty-five, Linda Jones saw that Adrianne was still awake, ironing her pants for school the next day. She seemed “sort of antsy,” Linda said. Linda told her to turn off the lights and go to bed.

Sometime after midnight, one of Adrianne’s younger brothers heard the constrained tumble of a slow-moving engine outside the house. When he looked out the window, he saw what he thought was a pickup truck driving away.

The next morning, Adrianne was nowhere to be found, and Linda and Bill thought she might have risen early to go running. But when they discovered her running shoes in her bedroom, they got anxious. Linda called Lee Ann Burke, the cross-country coach at Mansfield High, and asked, “Who is someone named David on the cross-country team?”

“Well, there’s David Graham,” Burke replied.

“Adrianne’s missing,” Linda said, “and I think he called her last night.”

Burke was baffled. She didn’t even know David and Adrianne were friends. David, a senior, was a decent cross-country athlete, but he was best known around the school for his position as battalion commander of the school’s Junior ROTC program. Burke sent April Grossman to David’s second-period math class to ask him if he had called Adrianne the previous night. David stared at April as if she were not making sense. “Did I talk to Adrianne? No. Why would I?”

As their investigation began, the detectives did conduct a perfunctory interview with David Graham, but they were so certain he was not involved that they didn’t even try to give him a polygraph test. For one thing, David’s name was not among the thirty or so listed in Adrianne’s personal phone book. Nor did the detectives hear his name mentioned by any of Adrianne’s friends when they asked who might have had a close relationship with her. In fact, Tracy Bumpass said that Adrianne told her all of her “deepest, darkest secrets,” but not once did she ever talk about David.

Besides, David had supposedly been seen with tears in his eyes at the memorial service, seemingly stunned like everyone else that Adrianne was gone. Few students considered themselves good friends with David—“We all knew him, but we really didn’t know him, you know?” said Kenny Grant, whose locker was next to David’s throughout high school—and he certainly was not part of the school’s most popular crowd. Still, he intrigued other kids. With his military burr haircut and ramrod posture, he seemed to be a throwback to a different era. The youngest of four children, David lived with his father, Jerry Graham, a retired Mansfield elementary school principal. He was divorced from David’s mother, Janice, a former teacher who lived in Houston. At the age of seven, after seeing his first air show, David told his father he wanted to become an Air Force pilot, and he never wavered from his dream. Although ROTC students at Mansfield High were usually the subjects of jokes—“We thought of all of them in their green uniforms as sort of geeky,” one girl said—it was clear that David was going places. He was a National Merit commended student (just below the rank of National Merit semifinalist), and Congressman Martin Frost had agreed to support his application to enroll the next fall in the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs. “Some of the more sarcastic guys in school would address him as Colonel Graham,” said Jennifer Skinner, who sat near David in a government class his senior year. “But you could tell they sort of said it out of respect.” Added another classmate, David Brennan, “He could fall asleep during class and then wake up and still answer the teacher’s questions.”

David Graham might have seemed tailor-made for the military—when he and others in the ROTC squadron presented the colors before the football games, he stood so perfectly still that people tended to watch him instead of the flag—but he never came across as one of those overly aggressive GI Joe types. He quit the football team after his freshman year because, it was said, he didn’t have the necessary ferocity to make it in Texas high school football. What’s more, girls liked him for his courtly manners. Angel Lockhardt, who was on the girls’ cross-country team, said David gave her rides home a few times after cross-country practice, “and he always acted like a gentleman.”

Plenty of girls would have dated David—“He was one of the last cool guys on earth,” a girl who served with David in the Mansfield High ROTC would later tell a reporter—but what few of them knew was that he already had a girlfriend. Her name was Diane Zamora, and she was a high school senior in the nearby town of Crowley. She was just as smart as David, and she was equally determined to get into one of the U.S. military academies. She was a member of the student council, the Key Club, the National Honor Society, and the Masters of the Universe, a science organization. She played flute in the marching band, and like David, she ran on her high school’s cross-country team. “When you looked at the two of them together,” one of Diane’s relatives said, “you just knew that a great future lay before them.”

The plan was to (and this is not easy for me to confess) break her young neck and sink her to the bottom of the lake . . .

The first major suspect to emerge in Adrianne’s murder was a Mansfield teenager, Tara (not her real name), who lived in a trailer park and already had something of a reputation around town. A year before, she thought her boyfriend had had a sexual encounter with one of Adrianne’s closest girlfriends. According to police records, Tara attacked the girl with a baseball bat, hitting her over the head, breaking her cheekbone, and leaving her with a concussion. Tara also shot and wounded her boyfriend. A restraining order was filed against Tara to keep her out of school and away from the girl she had attacked. At the hearing, Adrianne testified for her friend. Tara, in turn, allegedly told Adrianne, “I’ll get you for this.” Some students were convinced Tara was the killer. She fit their picture of what a killer would be: a surly, aimless individual far removed from the mainstream of suburban teenage life who had already shown her willingness to use a gun and a bat.

But the police discovered that Tara had a solid alibi, and she passed a polygraph test. Although Bill and Linda told the police they were suspicious of Adrianne’s boyfriend, Tracy Smith—Linda said he had never tried to contact the family after Adrianne’s killing—he too passed a polygraph.

Tracy did, however, give the police another clue. He said that Adrianne had told him that it was someone named Bryan who had clicked through on the phone that night. She had never mentioned David. She had said that “Bryan” was depressed and wanted to meet her that night to talk.

The detectives then learned that a Mansfield teenager named Bryan McMillen worked at an Eckerd’s near a Subway sandwich shop where Adrianne once worked. According to Adrianne’s friends and family, Bryan had become infatuated with Adrianne and often dropped by the Subway to see her. “He began to bother her so much that when she saw him coming, she started ducking her head behind the counter,” Linda Jones said.

The investigators’ suspicions were heightened when they discovered that the seventeen-year-old Bryan took four kinds of medication to battle symptoms of clinical depression. They asked him to come to the police station for an interview. According to an affidavit, Bryan first said he didn’t know an Adrianne Jones. Then he admitted that he did. A detective asked him if he had talked to Adrianne the night she was murdered. Bryan said he could have talked to her, but he didn’t remember. He had been drinking that night for the first time in six months, he said, and had become intoxicated. When asked why he had been drinking, Bryan said he had gotten upset because all of his friends had found girlfriends, but he hadn’t. He told detectives he felt like the “odd man out.”

It wasn’t hard for the police to put this scenario together: a lonely boy, unable to get the beautiful blonde from the high school to pay attention to him, devising a way to meet her late at night, then losing control. The detectives bored in, asking Bryan if he had gone to Adrianne’s house that night. Bryan said he might have. He said it was also possible he could have taken her somewhere. He just didn’t remember, he said.

A week later, in the pre-dawn hours of December 15, 1995, police officers armed with guns and a search warrant arrived at Bryan’s house. He was arrested for murder, and his pickup truck was impounded. This time, the story made the front pages of the newspapers, but several of Bryan’s friends defended him, saying that he was a gentle, slightly baffled kid who would never resort to violence. Bryan’s father insisted that the night of the murder, Bryan came home and never left the house.

Finally, after Bryan had spent Christmas and New Year’s Eve in jail, a lead prosecutor in the district attorney’s office arranged for a polygraph. “He not only passed,” the prosecutor said, “he passed with flying colors.”

Bryan’s release triggered more rumors, but no other suspects emerged. Because Adrianne’s brother had said that he had seen a pickup truck, the police ran computer checks to find any student who owned one. It never occurred to anyone that the vehicle her brother had seen might not have been involved in the murder. Nor, apparently, did anyone guess that Adrianne had told Tracy about a “Bryan” to keep him from learning about her relationship with someone else. Only months later would Tina Dollar, the manager at the Golden Fried Chicken, remember that Adrianne had once pulled a small photo of a boy out of her wallet and showed it to her.

“His name is David,” Adrianne had said.

. . . [Her] beautiful eyes have always played the strings of my heart effortlessly. I couldn’t imagine life without her; not for a second did I want to lose her.

David Graham and Diane Zamora first met about four years before Adrianne Jones’s murder, when their parents began dropping them off at a small airfield south of Fort Worth. They went there for weekly meetings of the Civil Air Patrol, an Air Force auxiliary organization that teaches the basics of the military life and leads search-and-rescue missions for downed aircraft. But there was no romance between them in their younger years. Despite her good looks, Diane was careful around guys. She did have a boyfriend during her sophomore year in high school, but the relationship was not particularly heated. When the two went out for dinner on Valentine’s Day, Diane asked to be taken home at eight-thirty because she needed to study. “She kept telling us she wanted to focus on her studies and her goals instead of on guys,” said her aunt Sylvia Gonzalez. “And she always made it a point to tell us she was never going to lose her virginity unless she got married. When two of her cousins got pregnant in high school, she said she couldn’t believe how stupid they were. She swore that nothing like that would happen to her.”

In the world of high school sexual skirmishing, Diane firmly put herself into the camp of “good girls.” A girl who goes too far, she would often say to her family, gets called a slut. When she realized during her sophomore year that her boyfriend was bent on having sex with her, she dumped him.

Diane’s father, Carlos, a kind, soft-spoken man, was an electrician; her mother, Gloria, was a registered nurse. The family was deeply religious. Gloria was the daughter of a minister who led a nondenominational Spanish-speaking church on the south side of Fort Worth. Gloria, her five sisters, and their families never missed Sunday services, and after church, the entire Zamora clan would gather for lunch at a cafeteria. Diane was the eldest of the Zamoras’ four children, and the most driven. When she was nine years old, she announced to her family that she wanted to become an astronaut. She sent off for NASA brochures, and by high school she was keeping a spiral notebook containing a list of achievements she had to accomplish to get a college scholarship. She knew exactly what her grade point average and SAT scores needed to be. She carried a knapsack full of schoolbooks everywhere in case she got stranded and had some time to fill.

At Crowley High School, Diane was not one of the social girls who gathered between periods in the school’s chalky-smelling hallways to swap gossip. While she was not considered unfriendly, she was known around school as someone who kept to herself. “She didn’t have a whole lot to say,” one student said. She preferred associating with the smart kids at school—“homework buddies,” she called them—and she was determined to become an academic star. Late in her junior year, when she posed for her high school graduation picture, she asked that she be allowed to wear the special tassel for being in the top 10 percent of her senior class—even though she had no idea at that time whether she would achieve that honor. Diane said she wanted to have the photograph as a way to keep her motivated.

Diane did end up in the top 10 percent of her senior class. Gloria Zamora told her friends that the reason Diane worked so diligently was because she knew her parents could not afford to send her to a good college. When her father got laid off from work, Diane watched Gloria take on two nursing jobs a day and then sell Mary Kay cosmetics on the side to help pay the family’s bills. At one point, the electricity was cut off in their small house for more than a week. Diane studied by candlelight. But even with her ambition, Diane was still a teenager, filled with the same impulses and longings as any other girl her age. While she kept Civil Air Patrol military fatigues in her closet, she also had a collection of teddy bears on her bed. She took an after-school job at Fast Forward, a store oriented to teenage girls, because she liked the discount she could get on hip clothes. She listened to both contemporary Christian music and popular groups like Pearl Jam. “Diane was a really sweet girl,” said one former neighbor, Dale Rogers. “But I thought she was a little naive and sheltered from the outside world. She was really a virgin in life, you know? She hadn’t really experienced anything. She didn’t know all the things that could happen between people.”

And then, in August 1995, just before the start of her senior year, her life changed. She told her parents that she had fallen for a boy: David Graham. He was just like her, she said breathlessly. It was not only that they had known as children what they wanted to do with their lives. They both loved calculus, physics, and government, and they talked on the phone late into the night about their homework. Their feelings, well known to any adolescent, were a mixture of adoration and total possessiveness. When they were together, they never stopped touching. Diane would put her arm around his waist, sliding one finger into a belt loop, and David would encircle her with his arms. “He always had both arms around her, like he was afraid she was going somewhere,” said Diane’s aunt Sylvia. “The two of them looked like they were wrapped up in one another.”

It was not difficult for David and Diane to be swept away by the romantic grandeur of their relationship. By then, they were the stars of the Civil Air Patrol—David was a cadet-colonel in the CAP’s youth division, the highest accolade given, and Diane was the wing secretary—and they saw themselves as the top guns of the twenty-first century. David saw himself becoming a great fighter pilot, Diane a famous astronaut. Abandoning her plans to study physics at an academically elite major university, Diane applied to the Air Force Academy, where David was set on going. After she learned that the deadline had passed for applications, she applied to the U.S. Naval Academy with the intention of transferring her commission after graduation from the Navy to the Air Force so she could be stationed with David.

Diane’s family knew that David’s personality was a little different. He had a collection of hunting rifles, which he once brought over to their house. When he came to church with Diane, he wore his combat boots, pants, and a T-shirt, and he kept his arms closely around her through the service. He once showed up at the Zamoras’ house with a couple of his ROTC buddies from Mansfield. For entertainment, David took them out to the front yard and ordered them to march back and forth. “Diane was laughing, thinking it was funny,” said Sylvia, “but I think the rest of us wondered a little when David said, ‘I can get these guys to do whatever I want.’ ”

Still, no one could say that David was ever impolite around Diane or her family. On weeknights he drove the eighteen miles from Mansfield to Crowley and quietly sat in the Zamoras’ living room to do homework with her. When her parents couldn’t afford a pair of $100 combat boots for Diane, David bought them. After Diane had a serious wreck driving David’s pickup truck, requiring pins to be put into her left hand, David spent entire nights at the hospital with her. “Unlike that other boyfriend of hers who just wanted to go all the way,” said a relative, “David genuinely cared for Diane. I don’t think Diane had ever had that kind of attention.”

That September, about a month after they started dating, they told Diane’s parents that they were engaged. David had sold a couple of his hunting rifles to make a down payment for an engagement ring. They were going to get married, they said, on August 13, 2000, after they graduated from their military academies. They already had the wedding planned. They were going to charter a bus to carry their relatives in Texas to the famous Cadet Chapel on the Air Force Academy’s campus. There, David would wear his uniform, Diane a white wedding dress, and at the end of the ceremony, they would walk under crossed swords held by other cadets.

Not long after they announced their engagement, her family confirmed, Diane lost her virginity to David—an act that had a dramatic impact on her life. “After it was over, she was real confused by what had happened,” one relative said. “I know she felt guilty because she had wanted to wait. But once she went through with it, she became more committed than ever to David. I remember her saying, ‘If I can’t be Mrs. David Graham, then I will die as Miss Diane Zamora.’ ”

Indeed, they were hopelessly in love, focused as laser beams on each other. In that classic teenage way, they developed their own secret love code. She called him Tiger (the Mansfield High School mascot was a tiger), and he called her Kittens. And they ended many of their telephone conversations with the words, “Greenish brown female sheep.”

Greenish brown is the color olive. A female sheep is a ewe. Olive ewe. I love you.

When this precious relationship we had was damaged by my thoughtless actions, the only thing that could satisfy her womanly vengeance was the life of the one that had, for an instant, taken her place.

On the first weekend in November, David traveled to Lubbock with other members of the Mansfield High cross-country team for the regional meet. Both the boys’ and girls’ squads had qualified, and the school provided them a large van for the trip. One of the students who went on that trip was Adrianne Jones.

In many ways, Adrianne was Diane Zamora’s polar opposite, an ebullient girl who knew how to charm guys and get them to look twice at her. When she posed for one studio portrait, she made sure to show some cleavage. Although she was far from sexually naive, she wasn’t overtly promiscuous in a way that would make her an outcast among the more popular girls. Diane, on the other hand, rarely put on makeup for school, and except for David, she thought most high school guys were immature. It is not known if anything happened between Adrianne and David in Lubbock. No one can remember whether they sat next to one another on the van or stayed up late talking at the motel. Some of Adrianne’s friends think she would have kept her distance from David. As one friend pointed out, Adrianne had her standards: She would never sleep with another girl’s boyfriend.

But something did happen when they returned to Mansfield. For whatever reason—perhaps Adrianne looked at David on that van and saw the kind of guy that even her father would like—she asked him to give her a ride home. They didn’t go straight to her house. Adrianne surprised him by asking him to take some turns that he knew were out of the way. They ended up behind an elementary school, where David parked the car, and he and Adrianne had sex—a brief but truly fatal entanglement.

Apparently they told no one. Their encounter seemed to have been an impulsive, one-night fling. But a month later, late in the evening, a friend of David’s who lived in the nearby town of Burleson heard a tapping at his window. David and Diane, their clothes bloodied, came through the window. According to the friend, David begged him to ask no questions. But the friend noticed that both David and Diane were upset. They lay on the floor and held each other. It was the same night Adrianne Jones disappeared from her home and was murdered.

But the friend never reported the incident to the police, and soon David and Diane were back to their old ways. Using his father’s credit card, David bought Diane and Gloria leather coats as Christmas presents. He got Diane’s engagement ring out of layaway so she could begin to wear it. On Valentine’s Day, he gave her a teddy bear and flowers.

Diane’s family could not help but wonder about the relationship as it progressed. David and Diane seemed so absorbed in one another’s lives . . . so obsessed. “No matter what we were talking about, Diane brought up David’s name. She was always talking about David this or David that,” said Diane’s cousin Ronnie Gonzalez. One night when they were apart and David didn’t call, Diane tearfully begged her mother to call his house to see if anything terrible had happened to him. David was no different. He came over every afternoon to run with Diane, and some nights he would stay so late that he would fall asleep on the couch. His father would call, demanding that he come home, but David would dawdle for hours before leaving. Whenever Diane would go to a school function at night, David would phone every hour from his home until she got back.

That spring, they learned within days of each other that they had been accepted to their academies—David to the Air Force, Diane to the Navy. At special ceremonies at their high schools, they were presented with their academy acceptance letters. The Mansfield students gave a long ovation to David, who had Diane at his side. “I know this sounds strange to say now,” recalled Becki Strosnider, the former editor of the Mansfield Uproar, “but we thought it was so cool that he had followed his dream.” For her part, Gloria was so proud of what her daughter had done that she called the Hispanic-oriented La Estrella section of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and suggested a story. When she spoke with David and Diane, the reporter, Rosanna Ruiz, asked them if they were being realistic about being married in five years, considering they would be so far apart. But the two insisted that they would stay in touch daily through e-mail. “I was surprised at how adamant they were,” Ruiz recalled. “They said they were certain the marriage was going to happen and that there were not going to be any outs. Then they stopped and looked at one another.”

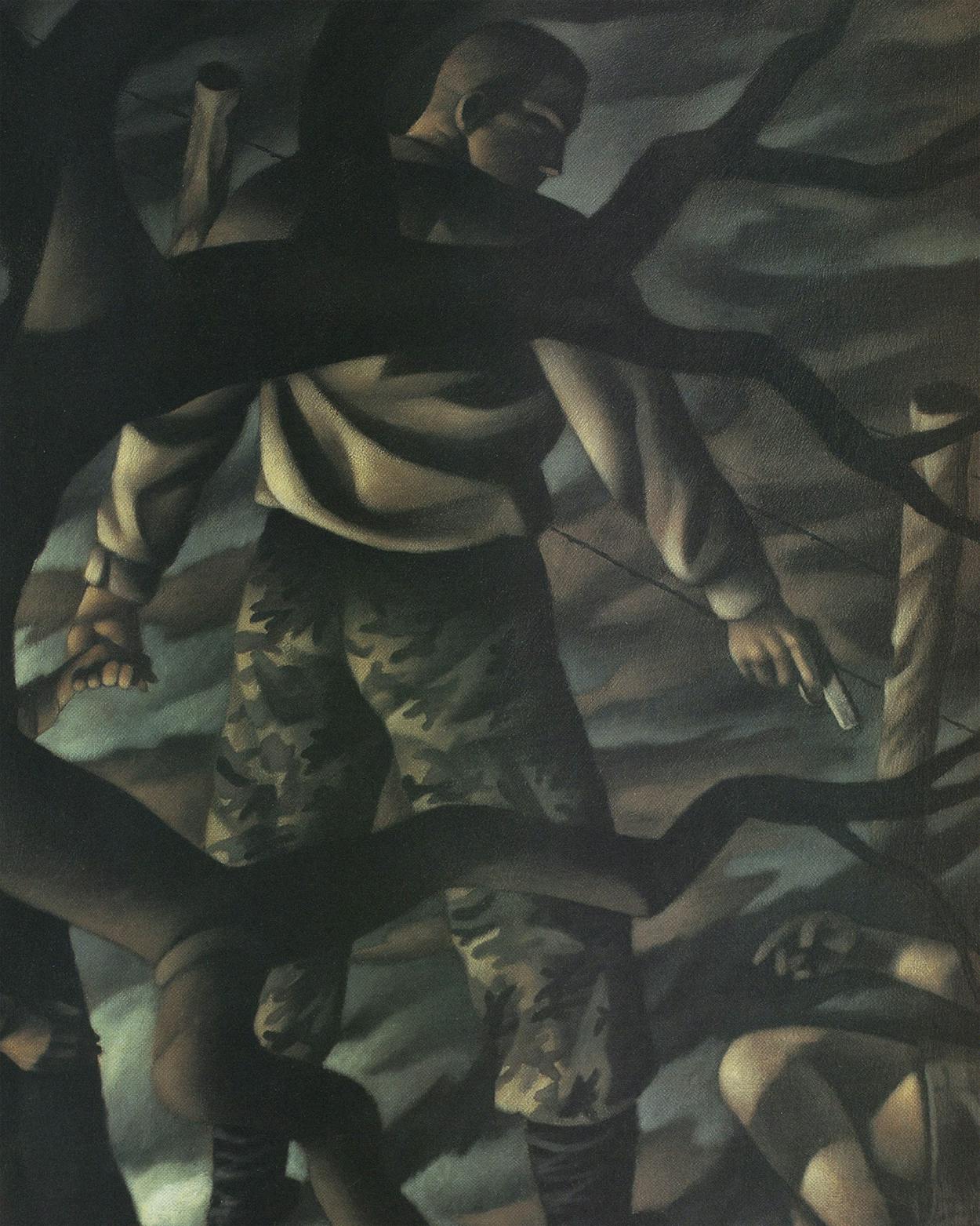

In the summer of 1996, after nearly three hundred interviews, detectives put the case on what they called slow-down mode. Bill and Linda Jones sank deeper into despair. Bill had to restrain himself to keep from interrogating every teenager he saw in town. Linda would get into her car at night and drive to the site where Adrianne was found, hoping she might come across the killer. Some students continued to see counselors about Adrianne’s death. April Grossman painted a portrait of Adrianne in art class to honor her. She showed it to David, who sat behind April in government. He looked at it, paused, and then said, “You did a good job, April.”

We realized it was either her or us . . . I just pointed and shot.

Only 1,239 young people were accepted out of the 8,736 who applied to enter the Air Force Academy for the fall 1996 semester. Of the nearly 10,000 who applied to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, only 1,212 were accepted, 200 of those being women. Just by getting into their academies, David Graham and Diane Zamora had become part of a select group of American teenagers. To stay there, however, they had to survive grueling summer boot camps designed to eradicate their civilian habits and teach them the exacting discipline of military life. For the freshmen at the academies—known as plebes at the Naval Academy and Doolies at the Air Force Academy—the six-week summer sessions were humid days of nonstop marching, push-ups, running, and taking orders. Upperclassmen belittled them every time they made a mistake. At meals, the freshmen were required to keep their eyes focused on their plates at all times except when questioned by a superior. They had to be prepared to answer a barrage of questions and recite long passages about academy rules from memory. The system was unnerving and often demoralizing, and it was not unusual to see a cadet or midshipman resign his or her commission before the summer was over.

By all indications, David successfully completed his Basic Cadet Training in Colorado Springs. According to relatives who read them, Diane’s letters home indicated that she was capably enduring “plebe summer” in Annapolis. She wrote in detail about her daily schedule, from the ninety-minute calisthenic sessions at six in the morning to the evening drill period in which they marched with M16 rifles. She wrote that she was going to church again at the Naval Chapel and that she had joined the glee club.

But her squad leader, Jay Guild, a good-looking plebe from suburban Chicago, said Diane was not physically keeping up with the other plebes and seemed emotionally distracted. “She liked to talk about David,” Jay said. “She missed him a lot. She often talked about him very strangely, as if she didn’t trust him but she still wanted to be with him. It was very odd.”

Jay said Diane went on “crying fits” when David wouldn’t answer her e-mail. She told him she suspected David was cheating on her with a female cadet at the Air Force Academy. Apart from David for the first time since they began dating, Diane became plagued with jealousy, and she decided, in turn, to make David jealous. According to one source, Diane stopped sending David e-mail for several days, telling him that her computer had broken. A few weeks into the plebe summer, Jay added, Diane told him that she was considering breaking up with David, and she suggested that the two of them become boyfriend and girlfriend. She then sent David an e-mail telling him that Jay had kissed her.

David and Diane, who once had found such security in their all-consuming devotion, seemed to be whirling out of control. When David heard about Diane and Jay, he attempted to contact Naval officials to inform them that Jay was sexually harassing Diane. He sent threatening e-mail to Jay, demanding that he have nothing more to do with Diane. One person close to the investigation said that David wrote Diane letters begging her not to deceive him. In the letters, David would write such lines as, “Remember what binds us together.”

It was clear that Jay was captivated by Diane. When Diane’s parents and Jay’s mother arrived in Annapolis for Parents’ Weekend on August 9, they were told that Jay and Diane had been reprimanded by upperclassmen for excessive fraternizing. He had been seen sitting on the edge of her bed at night at Bancroft Hall, the coed dormitory where all the midshipmen lived. The truth was that Gloria was relieved to hear the news about Jay and Diane. “I got the very strong feeling that Diane’s parents felt the relationship between Diane and David had become an unhealthy one,” said Jay’s mother, Cheryl Guild. At one point in the weekend, Diane and her parents went to lunch with Jay and his mother. During that lunch, Diane got up to call to David. Cheryl could see Diane across the room, talking on the phone, and she noticed the girl was physically shaking. Gloria leaned toward Cheryl and said, “I wish Diane had met Jay first.”

Jay said that at one point in the summer, he asked Diane if David had ever cheated on her before. “She said yes, and I said, ‘What did you do about it?’ She told me that she had asked David to kill the other girl.”

Stunned, Jay listened as Diane told him that she had watched David kill a girl named Adrianne. She never said she had participated. “All she said is that she told him to do it and she saw him do it,” Jay said.

Although the Academy’s strict honor code, known as the Brigade of Midshipmen Honor Concept, states that a midshipman must immediately report another midshipman who lies, cheats, or breaks the law in any way, Jay told no one—and would eventually be asked to resign from the Academy because of his silence. “I didn’t want to believe it,” he said. “I thought maybe she was trying to get attention.”

But in late August, Diane told the story again, this time to her two roommates, Mandy Gotch and Jennifer McKearney. They were having a late-night conversation, and one of the girls mentioned how Diane and David seemed so in love. According to an investigator in the case, one roommate said to Diane, “I bet you two would do anything for one another.”

Diane replied, “Yes.”

“Even kill for one another?” the roommate asked.

Diane paused. “We have,” she said. Then she told them the story about Adrianne—whether out of guilt or pride, no one is sure. Initially, the two roommates were skeptical about what they had heard, but the next day, they nervously told a Navy chaplain about the conversation. The chaplain contacted a Navy attorney at the Academy, who then began calling police departments in the Dallas–Fort Worth area to ask if they had an unsolved murder of a teenage girl. On August 29 he contacted the Grand Prairie police department. The next morning, detectives were on a flight to Annapolis.

I just wanted it to be a dream. . . . I wanted to be able to drive Adrianne back home, to go to sleep, and to wake up back on December 3, free to make my decisions all over again.

They pulled her out of the first pep rally of the season for Navy’s football team, the first night when the plebes were allowed to mingle with upperclassmen and feel a part of the Academy. Across the Yard came the sound of pounding drums and cheering midshipmen as Diane was escorted down a long hallway in the administration building and then was led into a room where several detectives and Navy officials waited.

She admitted to nothing. She said only that she had been insecure throughout plebe summer, and she thought such a tale about murder would make her look tougher in the eyes of other plebes.

The cops weren’t buying it, but what could they do? They had no evidence against her. Navy officials told her they were temporarily suspending her and sending her home until the matter was straightened out. They gave her an airplane ticket that took her from Baltimore to Atlanta and then on to Dallas. When Diane reached Atlanta, however, she changed planes and flew to Colorado Springs, where she went to see David.

No one knows what was said between them. But the two did have their photographs taken by a friend of David’s. David was wearing his Air Force uniform, Diane her all-white Naval outfit. In that one moment, they looked at the camera with a nearly desperate look, as if they knew that this was their last time together—that the fairy tale was over.

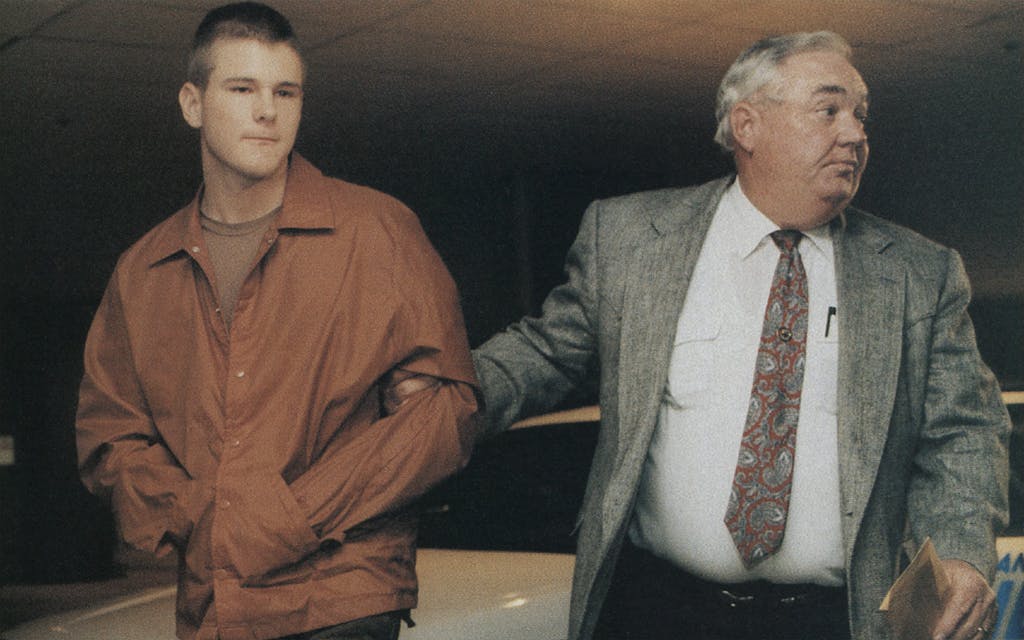

When the detectives arrived in Colorado Springs, David insisted that he couldn’t imagine why Diane would tell such a blatantly false story. But the cops told him they had found his friend in Burleson and had heard the story of the bloody clothing. Then the Air Force officers told the young cadet that he had a duty to reveal the truth. Finally, David broke. He sat down at a word processor and typed a four-and-a-half-page confession (reprinted in part in the Dallas Morning News) that one forensic psychologist would later equate with a Danielle Steele novel. David wrote that for a month after his evening with Adrianne, he was tormented by “guilt and shame.” The “perfect and pure” relationship between him and Diane, he added, had been defiled by “the one girl [who] had stolen from us our purity.” Eventually, he told Diane about his tryst. “For at least an hour she screamed sobs that I wouldn’t have thought possible. It wasn’t just jealousy. For Diane, she had been betrayed, deceived and forgotten.” He then said Diane gave him an ultimatum: kill Adrianne. David agreed. “I didn’t have any harsh feelings for Adrianne,” he wrote, “but no one could stand between me and Diane.”

And so, David admitted, he called Adrianne on the night of December 4, 1995, and said he wanted to see her. He picked her up in a Mazda Protege owned by Diane’s parents. Diane was hiding in the hatchback. They drove out to a secluded country road, and Adrianne reclined the passenger’s seat, no doubt hoping for another romantic interlude. According to David’s confession, while he held Adrianne, Diane raised up from her hiding place and hit her in the head with a dumbbell that belonged to David. Adrianne, however, did not die. “I realized too late that all those quick, painless snaps seen in the movies were just your usual Hollywood stunts,” David wrote. “Adrianne somehow crawled through the window and to our horror, ran off. I was panicky, and just grabbed the Makarov 9mm to follow. To our relief (at the time) she was too injured from the wounds to go far. She ran into a nearby field and collapsed. . . . In that short instant, I knew I couldn’t leave the key witness to our crime alive. I just pointed and shot . . . I fired again and ran to the car. Diane and I drove off. The first things out of our mouths were, ‘I love you.’ ” And then Diane said, her thirst for revenge suddenly slaked, “We shouldn’t have done that, David.”

The police recovered the handgun along with several dumbbells from the attic of the Grahams’ home. They also confronted Diane, who by then was back in Texas. She stared at the officers. Then she quietly went to the station to give her own confession. She was put in a solitary cell on a separate floor from David—she looked like a harmless teenage girl in a sleeveless shirt and blue jeans. Every day, she did push-ups and sit-ups in her cell. She asked her mother for history and government textbooks so she could continue her studies. She said little to the guards or to her fellow female inmates, except for one prisoner who regularly cried because she missed her children. Diane sang her a contemporary Christian song she had memorized back in high school titled “Faith.”

In Mansfield, as everywhere else, the question on everyone’s mind was, Why? It was one thing, residents said, to read about urban gang kids shooting it out over a rivalry, but how did the culture of the streets—where loyalty and vengeance are valued above life and law—infect upstanding small-town kids? There were the usual discussions about teenagers’ values being shaped more by shabby movie violence and the angry lyrics of their favorite singers than they were by moral lessons from their parents. Other citizens were shocked to learn that more than one of David’s closest friends suspected that David was involved in Adrianne’s murder, yet never said anything to the police. It was as if the most important thing among these teenagers was not “narc-ing” on a friend.

After the initial wave of national publicity over the arrests, Anna Barrett, a reporter for the Mansfield News Mirror, began looking for positive stories to write about the high school to help the community’s morale. “But something has changed in this town,” she said. “You can feel it.” Indeed, within a month after the arrests, a junior at Mansfield High was shot in the face with a shotgun and killed. A girl who had been on the cross-country team hanged herself because of personal problems. As for Bill and Linda Jones, they changed their phone number to avoid the phone calls from reporters, television shows, and movie producers. One producer, explaining why David and Diane’s would be a great miniseries, said in an interview, “It’s a modern-day Romeo and Juliet—only they kill someone else instead of each other.”

What remained unfathomable was how David and Diane could convince themselves that only death could eliminate the one blot on their perfect teenage love affair. How could they imagine that sexual betrayal was a far worse crime than murder? It seems clear that David convinced Diane that Adrianne was a seductress who lured him behind the elementary school. According to one police source, just before Diane hit Adrianne in the head, she looked at her and said, “I know who you are! I know what you’ve done!”

Perhaps a trial will provide the definitive answer to why they did it. The district attorney’s office has not determined whether it will seek the death penalty for the two eighteen-year-olds. There is an outside chance that David’s attorney, Dan Cogdell of Houston, will get David’s confession thrown out of court because he had been confined to his quarters at the Air Force Academy for more than thirty hours before the police took the confession. If a judge rules that the confession is admissible, however, then it is possible that Cogdell and John Linebarger, a prominent Fort Worth defense attorney who has been hired by Diane’s family, will try to position their clients to point fingers at each other. “If I think attacking the Zamora girl is the appropriate line of defense, I will do it,” said Cogdell, who added that he believes Graham wrote his confession to cover for Diane. A couple of investigators agree with him, believing that Diane had a Lady Macbeth–like control over David’s life, coaxing and taunting him into letting his impulses and desires overcome his scruples. But others suggest that David, who brought guns and violence, sex and betrayal into Diane’s sweet and studious life, exercised his spell over her by enlisting her as a partner in murder—using death to bind them together for life. There is even a third police theory that David, wanting to prove that he cared nothing for Adrianne, took one shot, and Diane, consumed with fury, took the other.

Still, it is difficult to imagine that David and Diane will someday turn into adversaries in court. When David was being escorted to the county jail in Fort Worth, a television reporter asked if he had anything to say to Diane. David looked at the camera and said, “I love you.” As for Diane, one afternoon she motioned toward a guard and asked if she would pass on a message to David.

“What is it?” the guard asked.

Diane paused. “Tell him, ‘Greenish brown female sheep.’ ”

- More About:

- Military

- Longreads

- Crime

- Mansfield

- Fort Worth