This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It seemed inconceivable that some damned fool would steal Parnell McNamara’s daughter’s horse, in broad daylight no less. Though there were about fifteen horses in the McNamara family stable in Bosqueville, west of Waco, the thieves targeted the two horses penned behind the family rodeo arena, just across FM 1637. One was Marisa McNamara’s beloved sorrel mare, Penny, and the other a registered quarter horse named Mr. Deck Note, owned by a close friend, Tonia Smith. Horse-trading is a primary occupation in the rural areas of Central Texas, and the sight of men loading horses into trailers in the middle of the day didn’t attract attention. It was a cool and clever operation, its very ordinariness providing ideal cover. In any other place, at any other time, it might have been the perfect crime.

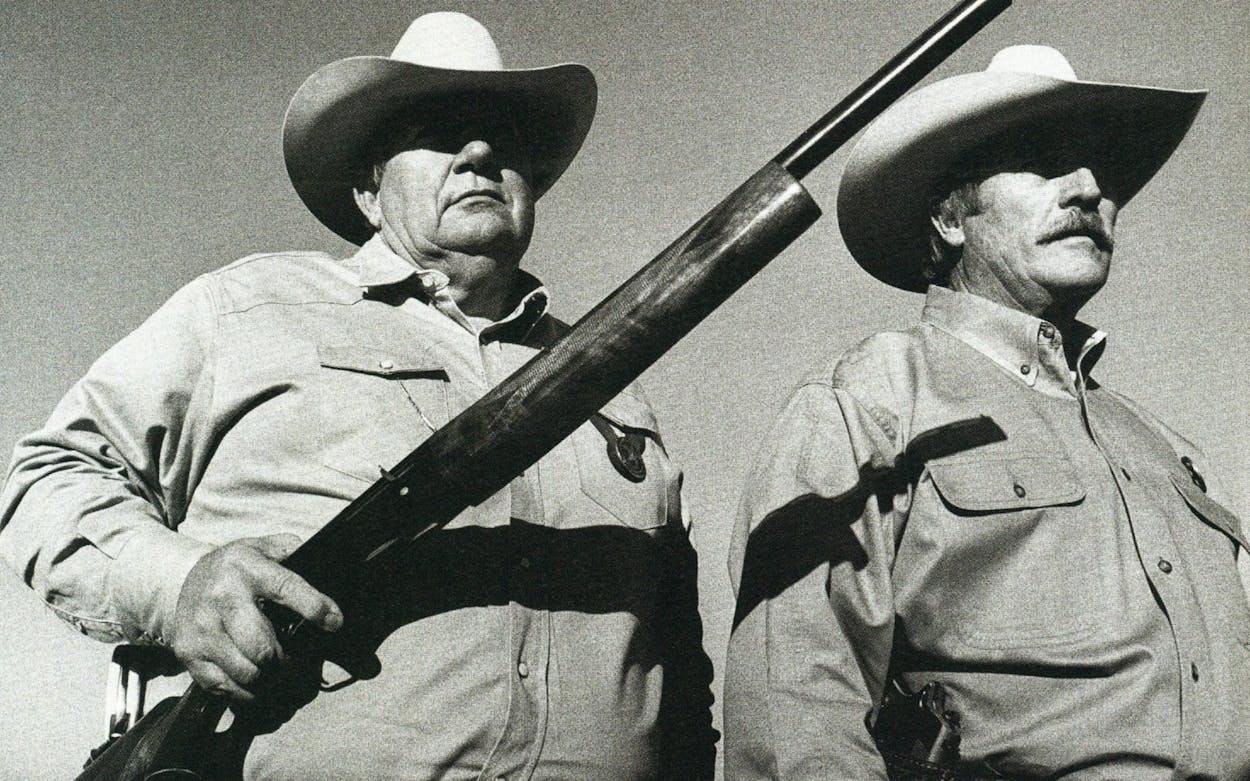

What the crooks didn’t know on that June 1996 afternoon was that Parnell McNamara, 51, is a deputy U.S. marshal with a reputation for inordinate stubbornness. Parnell is a throwback to a time when a select few made it their mission to track down—simply because it was the right thing to do—elusive bad guys. Like serial killer Kenneth McDuff, whom Parnell and his 50-year-old brother, Mike, also an ornery deputy U.S. marshal, had trailed and help corral. On the day of the horse theft, Parnell was on his way to Seagoville to deliver a load of Bandidos motorcycle gangsters to the federal prison when his 19-year-old daughter called him on his mobile phone with the terrible news.

A tall, leathery man with a dust-colored mustache and the steely gray eyes of a wolf, Parnell took the information in his usual stoic manner. “I’ve got a load of crooks right now, honey,” he told his daughter, “but I’ll be there as soon as I can.” The note of desperation and the sense of loss in Marisa’s voice must have touched a raw, primal nerve in the lawman: Stealing a horse was one of the most personal of violations, not altogether different from kidnapping a child. One does not trespass on such hallowed ground. Less than 24 hours earlier, Parnell had been helping his daughter practice her barrel racing in that very arena, as they did almost every night after work. No girl ever loved a pet more than Marisa loved that mare. Now the horse was gone, and the chances of recovering her were slim.

Once his prisoners were delivered, Parnell wheeled the prison van around and sped toward Waco. Though the crime was the jurisdiction of Waco city police, he wasn’t about to wait for justice to take its customary course—down a dead-end street, likely as not. Within a few hours he and Mike had rolled resolutely into action, printing and distributing posters with a photograph of Mr. Deck Note—unlike the plain-colored Penny, Mr. Deck Note had an easily identifiable white spot on his rump—and offering a $2,000 reward. Crime Stoppers offered an additional $1,000 and videotaped a reenactment of the crime that was shown on the local news.

Finally, they fell back on a century of Texas law enforcement tradition, recruiting an old-fashioned posse among close friends. The posse included Secret Service agent Robert Blossman, assistant U.S. attorney Bill Johnston, and Special Ranger Eddie Foreman. Though outsiders might have thought it legal overkill, the posse was the sort of reaction folks in Waco have come to expect from the McNamaras and their friends. “How long has it been since the U.S. marshals, the U.S. attorney, the Secret Service, and the Texas Rangers galloped across the prairie in pursuit of horse thieves?” Johnston mused from his office on the banks of the Brazos River in Waco, his face flushed with pride. “Probably, you have to go back to the James Gang.”

The McNamaras and their ad hoc posse are the spiritual descendants of an unforgiving school of frontier lawmen who recognized the fundamental, unbreakable bond between man and horse. A horse was among the necessities of life in the nineteenth century. “If a thief stole your horse and left you afoot halfway between Waco and Austin, it was a death sentence,” says the posse’s commander, Eddie Foreman, a field inspector for the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association (TSCRA) and Texas Ranger. A good horse was likely to be a man’s closest companion and the last creature he would abandon in a crisis. The law of the frontier paid tribute to this bond, brooking no excuse and advocating every possible effort to bring horse rustlers to justice.

Until the present century, hanging was the legally prescribed punishment, though sometimes not the most convenient one. In 1874 an outraged mob broke into the Bell County jail in Belton and shot to pieces nine suspected horse thieves. (Stealing cattle was also a hanging offense but with some variations in style. Cattle thieves caught in the act were almost always hanged on the spot, since herding the outlaws along with the pilfered cattle back to town was universally viewed as inexpedient.) Quasi-legal posses flourished in the nineteenth century. One particularly effective group was Colorado’s Uplift Society, so called because of its motto: “It is essential to forgive all horse thieves, and they can best be forgiven after they are hanged.”

Many of the folks I spoke to at the J&J Trading Post in Bosqueville tended to agree with this traditional philosophy. Five other horse stealings had been reported in the previous nine months, along with some missing saddles and tack. A stolen horse had been tied to a tree and shot. Anger and frustration ran deep in the communities of Bosqueville and China Spring. Stolen horses are difficult to recover—in only one of the five cases had any been found—and the thieves harder still to prosecute. Reddish-brown horses like Marisa’s sorrel, for example, all look the same to most jurors. Most owners don’t bother branding horses, and without a brand or some other identifying mark (such as a lip tattoo), proof of ownership is subjective. Some breeder’s associations require their animals to be DNA-tested before registration, but the time and expense of testing every animal suspected of being stolen make this an ineffective tool for investigators.

Leslie Wilch, a Baylor graduate student whose horse, Gypsy Queen, was swiped from the China Spring stables of the Baylor University Riding Club, told me hopefully but erroneously, “Technically, it’s still on the books that you can hang horse thieves. I wish they would do it now.” Rancher-businessman Harold Cobb, who had lost a horse and two saddles to thieves, considered sleeping in his barn with his shotgun, in case they returned. Reflecting on this prospect, he lamented, “The way the law reads now, if I shot the bastards, I’d be the one in trouble.” The way the law reads now, stealing a horse is no worse than stealing a TV set: Unless a thief steals more than ten horses, or horses worth at least $20,000, the scoundrel won’t even serve prison time. Today horse theft is the lowest class of felony, punishable by no more than two years in state jail and a fine of up to $10,000. Probation is mandatory for first-time offenders. Something has been lost, something deep in our character. Without most of us realizing it, the crime of horse stealing has faded from our collective outrage.

In most cases, thieves haul the stolen horses to one of the numerous auction barns around the state, where they are quickly sold as workhorses or as animals destined for one of the two slaughterhouses in Texas: Bel Tex in Fort Worth and Dallas Crown in Kaufman. Though horsemeat is not approved for human consumption by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, it is regarded as a gourmet item in some European markets. Restaurants in Paris and Brussels pay up to $15 a pound for horse tenderloin. (The less-choice cuts of horsemeat are processed and sold back to American shoppers as dog food.) To protect themselves from incriminating evidence, thieves sometimes cripple horses that are easily identifiable, cutting a tendon below the knee or driving a four-inch nail up the quick of the animal’s hoof. Horses that limp into the auction barn are automatically doomed for the “killer market.”

Middlemen for the slaughterhouses haunt auction barns, buying lame or worn-out or otherwise bargain-priced horses for a couple hundred dollars. There’s no room for sentiment in this grisly trade: Buyers look at a horse like Penny and don’t see a pet or an image of our Western heritage. They see one thousand pounds of hanging meat, at 65 cents to 85 cents a pound. The killer market establishes the minimum price of horseflesh. In 1983, when the horsemeat market plunged to 10 cents a pound, a horse dealer in Falls County starved his herd because it was more cost-effective than shipping horses to the slaughterhouse.

The Texas Legislature took steps last session to protect stolen horses from ending up on the grill, passing a law effective September 1997 that authorizes officials from the TSCRA to inspect each horse purchased by a slaughterhouse. But with Bel Tex killing four to five hundred horses per week and Dallas Crown two to three hundred, some stolen animals get past the inspectors. The killer market is legal, of course, even defensible: “It’s the best thing that ever happened to the horse business, because it gets rid of a lot of cripples or crazies,” says Larry Gray, a TSCRA supervisor in Fort Worth.

That’s one point of view. Another was expressed by Lonesome Dave Snyder, an old cowboy who for the past four years has lived in McNamara’s stables with his horse, Diamond. Lonesome Dave explains in his pained, serious way: “Me and Parnell, we don’t just have horses, we love ’em. Back in my drinking days, I’d ride bareback up to the store. I’d hold up two fingers, they’d bring me out two beers, and so on through the evening. Eventually I’d go to sleep and Diamond would take me home. He’s more than a horse, you see. He’s my buddy.” For months after the thefts, Lonesome Dave sat up all night, a ten-gauge sawed-off shotgun in his lap and an authentic thirteen-knot hangman’s noose dangling from a rafter above his head. He borrowed the noose from Parnell, who had learned the all-but-forgotten craft from an old deputy sheriff. When something is weighing on Parnell’s mind, as it was after the break-in, he sits alone in a camp chair at his stable, absentmindedly tying nooses, the way some folks doodle.

The Uplift Society is a relic of bygone days—we don’t hang horse thieves anymore. But it’s still okay to assemble a posse. This one couldn’t have had a better commander than Eddie Foreman, a large, jovial man whose infectious sense of humor belies an unyielding commitment to the law. Like all field inspectors for the TSCRA, Foreman is a commissioned Texas Ranger, an arrangement that dates back to 1893 and pays homage to the state’s emotional and economic bonds to its livestock. Foreman was a cowhand before getting into law enforcement 31 years ago, and he acknowledges that some livestock are more equal than others, at least emotionally. “Who loves a cow?” he says with a laugh.

Foreman’s blue-ribbon posse was as relentless as it was historically deep, starting with the McNamaras. Parnell and Mike’s great uncle Guy McNamara, was the McLennon County constable from 1902 to 1915 and later the chief of the Waco Police Department, a deputy U.S. marshal, and finally, the U.S. marshal for the Western District of Texas, from 1933 until his death in 1947. Their father, the legendary T. P. McNamara, ran the U.S. marshal’s office in Waco for 37 years and was so dedicated to his hometown that in the sixties he turned down a chance for promotion—to full U.S. marshal—to stay in Waco. His sons are cut from the same timber: When Parnell and Mike joined the United States Marshals Service in 1970, fresh out of Baylor, they agreed to waive all pensions and benefits for a promise that they would never be transferred to another city. Mike and Parnell’s duties are not that different from their father’s: tracking down federal fugitives, serving federal warrants, and transporting federal prisoners.

Everything about Parnell echoes tradition, including his strong will and direct manner. He lives in the house his great-grandfather built shortly after the family emigrated from Ireland in the 1870’s. Parnell’s no-nonsense commitment to the law is exemplified by his massive personal arsenal, which includes two highly lethal weapons once owned by his father—a 1928 Thompson submachine gun and “Shorty,” a prepare-to-meet-your-maker extremely short double-barreled shotgun with a pistol grip. Mike is reserved and less physically menacing than his brother, but he is more intellectual, and his almost infinite patience makes him a serious threat to outlaws. Friends joke that Parnell is always late, but Mike makes up for it by being early.

Bill Johnston and Robert Blossman are also the sons of well-known lawmen. Like the McNamaras, they speak of their famous fathers as though they were a living part of their lives and memorialize them in dozens of portraits that wall their homes and offices. Johnston grew up in Dallas, where his father, Wilson Johnston, was a crusading assistant district attorney under Henry Wade during the wild fifties and sixties. “He used to ride night patrol with [Sheriff] Bill Decker, tracking down criminals,” Bill says, dropping his gangling six-foot-five frame deep into his swivel chair, flopping his boots on the desk, and enjoying the view of the Texas Ranger Museum across the freeway. “I involve myself as much as I ethically can with agents from other bureaus because that’s what my dad did.” Bill, who is 38, graduated from Baylor School of Law and in 1987 became the first assistant U.S. attorney permanently assigned to Waco.

The 44-year-old Blossman came to Waco in 1985 as the city’s first full-time Secret Service agent and remains a one-man bureau. He grew up in the nearby Hill Country—first in San Saba, where his father was a deputy sheriff, and later in Johnson City, where his father was a special agent for the Secret Service and was assigned to the LBJ Ranch. Lyndon Johnson took a liking to Ben Blossman, impressed by the way the agent could field-dress a deer. Robert was an all-around athlete at Llano High School in the early seventies, though rodeoing was his favorite sport. He also rode bulls and bareback bucking broncos and wrestled steers at Southwest Texas State University. On his father’s advice, Robert applied for and was accepted as a Secret Service agent in 1976. When Ronald Reagan was elected president in 1980, Robert was assigned to the presidential protection division, traveling to China, South America, and Europe with the president. Reagan, of course, was a famous horseman himself, and Robert’s background got him the assignment of riding along when the president galloped across his ranch in California, down Virginia bridle paths, or over South American pampas. Blossman has the same dogged devotion to duty and love of the chase as the other members of the posse, and he sometimes quotes this line from Ernest Hemingway: “There is no hunting like the hunting of man, and those who have hunted armed men long enough and like it, never care for anything else thereafter.”

Blossman, Johnston, and the McNamaras see and talk to one another regularly at the federal courthouse, ride together on weekends, and gather for large family outings. Parnell and Robert used to team-rope at Central Texas rodeos. Unfortunately, the tight bond of friendship that unites them is rare among agents from assorted law enforcement groups. In most cities turf wars and backstabbings are the norm, not just between agencies but within the ranks of the same bureaucracy. While these four old friends have taken their share of flak for their independence—and may get some more following the current media attention to this case—their style has often produced spectacular results, snaring in the federal net hardcore felons who might otherwise have slipped away from state authorities.

The most infamous was serial killer McDuff, whose appetite for raping and killing young women had been a topic of conversation in the McNamara household since the sixties, when T. P. McNamara first tangled with him. McDuff would eventually be sentenced to death for the murder of three Fort Worth teenagers. But in 1989 McDuff was inexplicably paroled. That same month police officers began finding the bodies of young women along the Interstate 35 corridor. Over lunch in downtown Waco, the McNamaras and Johnston, the U.S. attorney, discussed their strong suspicions that McDuff was the killer and complained that state and local authorities were ignoring this obvious lead. “We festered and fumed over it at lunch,” Johnston recalls. “That afternoon I found a deputy sheriff who had an informant who had gotten a tab of LSD from McDuff. Any state drug crime is a federal drug crime if we choose to take it, and marshals have jurisdiction over drug cases.” On the basis of the informant’s statement, a federal arrest warrant was issued. The McNamaras led an armada of lawmen who tracked the killer down and turned him over to the state for trial. McDuff received two death sentences and waits for his final justice.

Similarly, the state was able to make its eventual case against Ricky Kevin Smith, a suspect in the brutal rape and murder of an eleven-year-old Waco girl, Cheryl Logan, only because Robert Blossman discovered that Smith was also wanted for the federal offense of forging a government check. Johnston secured a warrant for Smith’s arrest. Armed with the warrant—and backed up by the McNamaras and Parnell’s trusty sawed-off shotgun, Shorty—Blossman chased the suspect from his housing project, across a vacant lot, through a mob of his angry friends, and then hauled him to jail. Smith got ten years on the check charge. While he was doing federal time, the state managed to collect evidence to indict him for the wanton murder of the girl.

“Bill Johnston believes in looking not just at the particular crime but at the individual—who he is, what he’s capable of doing,” Blossman says. While Johnston cannot actively participate in raids, he often stands by to advise agents on the law and draft warrants. He explains it this way: “Because we are sons of lawmen, we are especially tormented by crimes. We look for reasons to get involved. We believe it makes the community safer.” Adds Foreman: “The reason our area is not overwhelmed with crime is that we have peace officers who work together and a prosecutor who is not only willing to take the cases but devotes time to making the charges stick. Bill Johnston has done more to promote good relations between local and federal agencies than anyone in any place I’ve ever heard of.”

In the beginning Foreman and the others kept Parnell at arm’s length from the investigation, since he was technically a victim. That didn’t prevent the McNamara brothers from doing their own detective work. “This called for old-fashioned legwork,” Mike McNamara observes. “You don’t catch a horse thief by pecking on a computer.” Every morning and every evening after work, they tacked up posters in pawnshops, feedstores, sporting goods store, cafes, and other public places. They questioned horse traders, interviewed informants, and traded tips with other lawmen. Within a week, people began giving names to the posse.

Two names in particular emerged as prime suspects—Gary Hoctel, 43, and Lonnie McNew, 50, a pair of drifters from Ohio who had arrived in Central Texas about a year earlier, shortly before ranchers began reporting the thefts. (A third name the lawmen heard was Matthew Rothesbarger, a friend of Hoctel’s who had moved back to Ohio.) Hoctel, a horse trader by profession, had acquired free title to a handsome, well-equipped hundred-acre horse ranch in China Spring, a ten-minute drive from the McNamara ranch. McNew, who trained and raised horses, rented a smaller spread near Robinson. A number of witnesses had heard Hoctel and McNew brag that they were selling horses with phony registration papers. A woman who was being held in the McLennan County jail informed the posse that Hoctel kept a briefcase full of phony registration forms.

Foreman suspected that the two missing horses would eventually lead them on this paper trail. Though hunting down horse and cattle thieves is the TSCRA’s raison d’être, he spends much of his time dealing with con men who forge or switch registration papers to sell cut-rate nags for Thoroughbred prices. “It’s like they’re buying Hyundais and selling ’em as Mercedes-Benzs,” Foreman explains. Breeder’s certificates are fairly easy to alter. Many breeders merely sign the form and fill in the names of the sire and the dam, leaving blank the boxes indicating the age, sex, and color of the colt or filly. “A crook could buy a solid-colored paint cheap, say $300, sell that horse to the slaughterhouse or wherever, but keep the registration papers,” says Foreman. “Meanwhile, he’d look for a loud little paint, finish filling in the papers, and sell him for $2,500.”

One good source for blank certificates is the killer market, where papers of horses long since slaughtered are bought and sold. Another is auction barns. “I grew up around auction barns,” Blossman tells me. “You heard it all the time: ‘I’ll sell you the horse, but I’m keeping the paper.’” In many ways the altering of registration papers is far more serious than stealing or even selling Hyundais as Mercedes: Cars can’t breed, but an Appaloosa passed off as, say, a paint can contaminate an entire herd. “It might take a breeder ten years to discover that one of his horses has phony papers,” Foreman explains. “By that time, his gene pool is contaminated, his reputation ruined, and he’s out of business.”

The posse’s big break came on September 6, about ten weeks after the theft, when Parnell received a telephone call from Teresea Erwin, who had bought a horse from McNew in May. The registration papers turned out to be phony. A banker by profession, Teresea and her husband, Randy Erwin, started a small horse farm on the edge of Gatesville in 1993, breeding and showing registered paints. Paints are a popular breed because of their loud color patterns—white on red or white on black. The Erwins knew there were risks: there’s a fifty-fifty chance the offspring of a loudly colored sire and dam can be born solid, which in breeders’ language means without color. Solid paint colts are worthless as breeders.

Teresea was looking for a trainer for a newly purchased mare when she was introduced to McNew at a horse show in Belton in February 1996. McNew had droopy, watery eyes and walked with a limp, but his looks were softened somewhat by a sort of country charisma. Impressed with his riding ability and his supposed credentials, she hired him. McNew was such a good trainer the Erwins didn’t see the con coming.

One day while the Erwins were visiting McNew’s ranch, he tried to convince them that they needed a quarter horse stud to upgrade their operation. Of course, he had one for sale, a shiny black colt named Malachi. The Erwins bred paints, not quarter horses, but McNew informed them that good breeders hedge their bets. “Color breeds, like your paint, your Appaloosa, your buckskin, your palomino, they’re hot right now, but they can turn cold on you real quick. Over the long haul your blood breeds, like your quarter horse, are your best bet.” McNew gambled that the Erwins were too inexperienced to know the rules: that the offspring of a quarter horse stud and a paint mare cannot be registered as a quarter horse. He also gambled that they wouldn’t realize that Malachi wasn’t a quarter horse at all, but a solid-colored Appaloosa. “McNew saw us for what we were—novices, hungry for knowledge,” recalls Teresea, a petite forty-year-old.

The Erwins wisely declined on the black colt, but McNew was back in a couple weeks with another offer—a registered white-on-red paint filly with an outstanding bloodline for an unbelievably low price. He told the Erwins that he and Gary Hoctel—whom he introduced as his nephew—had bought the horse from a woman in Hillsboro named Betty Miller. Hoctel was younger and more articulate than McNew, and also more arrogant.

When Teresea got a close look at the horse, her heart sank. “Her eyes were white and wild, and she was so nervous you couldn’t touch her,” she says. “She had a respiratory infection, what we call ‘the snots,’ and she was thin and malnourished.” Still, $2,500 sounded like a good price, and the Erwins couldn’t say no. Determined to train the filly herself, Teresea worked with the horse twenty to thirty hours a week for more than three months. The filly gradually gained weight, got over the snots, and came to trust Teresea enough to follow a voice command and allow herself to be led into a trailer. Teresea was feeling the exhilaration of a miracle when a telephone call shocked her back to reality.

The caller identified herself as Betty Miller and said to Teresea: “You bought a paint filly out of my mare? Well, I’m sorry to tell you this, but my mare didn’t have a filly, she had a colt—and it wasn’t a paint.” Miller had indeed sold two solid colts to McNew and Hoctel. Though the colts had outstanding bloodlines, they were worthless to her breeding program and not worth registering. Miller had left the age, sex, and color boxes blank on the certificate. McNew easily transformed a solid colt into the loud paint filly that he sold to the Erwins.

Miller had learned about McNew’s scam from his old pal, Hoctel—apparently McNew and Hoctel had a falling out and this was Hoctel’s revenge. Teresea’s filly actually came from a killer auction in Waco, what Hoctel called a Thrifty Nickel. At this point Teresea didn’t know who or what to believe. She telephoned the auction and eventually learned that the filly had come without papers from New Mexico and had been bought by a man named McNew for about $500.

When the Erwins confronted McNew, he denied that the papers were phony but promised to return their money, which he eventually did. In the meantime a warm and sympathetic Hoctel telephoned Teresea out of the blue, advising her that the best way to get her money back was to do what they did—cheat. Keep the papers, shut her mouth, breed the mare, sell the babies, make money. “Everybody does it,” he told her. Teresea said she couldn’t do that. “It’s only a big deal if you make it one,” the con man replied. “Did you like the filly before Betty called? Then button your lip, slap her on the ass, and that’s what she is!”

As soon as he’d heard Teresea’s story, Eddie Foreman suspected that the crooks were running a double con, with one selling her the horse and the other telling her what happened and recruiting her to be part of the scheme. “If Teresea did what Hoctel told her,” Foreman theorized, “they’d come back later and shake her down.”

Erwin decided to call Hoctel back, this time with a tape recorder. Unaware that he was being recorded, he spilled the whole operation, careful to make it appear that McNew was the bad guy. McNew had swindled a number of horse owners in Florida and Georgia, Hoctel said, including a former catcher for the Oakland Athletics. When he first arrived in Texas, in 1994, McNew traded a rancher in Elmont two months’ worth of riding for a sorrel stallion named Zan Parr Majors, a son of the world-champion quarter horse Zan Parr. Hoctel didn’t think much of the horse’s looks or potential virility: “He was just a nickel hunting change.” McNew bought a stack of phony papers from a Waco man who specialized in the killer trade and put papers on a colt, claiming he was the son of Zan Parr Majors. Says Hoctel: “Then he made out a stallion report like he’d bred all these mares to Zan Parr Majors. But he had no mares—they were all phantoms!” Eventually, after a series of phone calls, faxes, and letters, Hoctel and McNew sold the bogus colt—as well as Zan Parr Majors and some other horses—to a breeder in Oklahoma.

U.S. attorney Johnston had been looking for an opening—a way to give their mixed-pedigree posse federal jurisdiction—and now he saw it. Horse stealing isn’t a federal crime, but mailing or faxing phony papers to perpetrate a fraud scheme certainly is. Eddie Foreman had collected an impressive array of witnesses and additional evidence, including the set of phony papers given to Teresea Erwin and the incriminating tape she had made of Hoctel. The posse had tracked down the trucker who hauled the wild-eyed filly to the Waco auction from New Mexico; he remembered the horse distinctly. Another witness had seen the filly on the auction block and heard Hoctel call out to McNew, “Buy that filly. I got papers to match her!” That was more than enough to get a search warrant. Everything in order, Johnston telephoned Blossman and the McNamaras, and Foreman’s posse galloped into action, serving Hoctel and McNew with warrants and searching their ranches.

To everyone’s surprise, Hoctel freely admitted that he altered registration papers: “Every horse trader does it,” he told the posse. He showed them his briefcase of phony certificates. He also showed them a videotape of the spurious colt. But Hoctel denied stealing Marisa McNamara’s horse or anyone else’s. “I’ll screw you out of your last penny and laugh when your kids go hungry,” he boasted. “But I never stole a horse!” Later, a polygraph expert found that Hoctel was being deceptive on the question of horse stealing. McNew denied everything, but the posse found plenty of incriminating evidence at his home, including a catalog for the Shawnee sale with the page touting Zan Parr Majors’ supposed colt conveniently dog-eared.

Eventually, the posse developed evidence pointing to Hoctel as the mastermind of the theft at the McNamara ranch but indicating that McNew wasn’t there. The second man at the crime scene was Matthew Rothesbarger, Hoctel’s friend from Ohio. When subpoenaed to come back to Texas and subjected to several polygraphs, Rothesbarger admitted that he had helped load Penny and Mr. Deck Note into Hoctel’s trailer, though he said he believed that he was assisting in a sale, not taking part in a crime. A few days later the horses were hauled to the auction barn in Groesbeck.

Searching records at the auction, the posse discovered sales receipts for two horses that matched the descriptions of Penny and Mr. Deck Note. Penny was purchased by the same killer trader who Hoctel said sold the bogus papers to McNew, and Mr. Deck Note was purchased by a roper from Mexia who had outbid the killer trader by a mere $5. Marisa’s mare was one of the two hundred or so horses slaughtered at Bel Tex a day or so after the auction, but Tonia Smith’s quarter horse was recovered—haggard, frightened, three hundred pounds lighter, but basically okay. “When I saw Tonia crying and throwing her arms around that horse,” Parnell told me, close to tears himself, “that moment made the whole thing worthwhile for me.”

In October 1997 Hoctel and McNew decided against a jury trial—where a Secret Service handwriting expert was ready to nail them—and pleaded out to federal fraud charges. Hoctel is doing ten months in federal prison and faces state charges for horse theft when he gets out. McNew did four months of home detention and is on probation for five years. Hoctel’s attorney complained that if it hadn’t been Parnell’s daughter’s horse that was stolen, none of this would have ended up in court. He’s probably right. As far as anyone can tell, this is the first time a stolen horse has led to a conviction in federal court, at least in modern times. As for the argument that everyone alters registration papers, that too is a given.

“It was just their bad luck to have picked this place,” Eddie Foreman concludes, chuckling merrily at the irony. “I tell horse traders: Before today, you could get fifty dollars for a set of bogus papers. If I catch you after today, you’ll get five years in the federal pen.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Horses

- Crime

- Waco