Nobody could make sense out of what happened to Mark Kilroy. It was all mixed up with black magic, white magic, drugs, mestizo superstition, gringo hedonism, coincidence, and random selection. We had warned ourselves about this sort of thing many times and still didn’t believe. It was the curse of el otro lado — the other side. Antonio Zavaleta, an expert on curanderismo who teaches at Texas Southmost College in Brownsville, was sometimes called to the other side of the border to supervise ghostbusting. “Look,” said Zavaleta, who had taught sociology and anthropology to two members of the murderous gang responsible for Kilroy’s death, “I’m a scientist. I have a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Texas. But when I went over there, I put a cross around my neck.”

By the time Mark Kilroy’s body was found on April 11 at Rancho Santa Elena, his disappearance had been the subject of fascinated media speculation for a month. The 21-year-old junior at the University of Texas had gone to South Padre Island along with thousands of other students during spring break and had simply vanished one night in the border town of Matamoros. From the beginning his disappearance seemed like an eerie and arbitrary event — a true mystery. When Kilroy’s fate was finally known, the mystery was even greater, because few of us were conditioned to accept the reality of human sacrifice to Satan.

Officials on both sides of the border had begun to suspect black magic a couple of weeks before the bodies of Kilroy and fourteen others were discovered. A psychic had reported a vision in which Kilroy’s body appeared alongside what looked like a witch’s caldron. A satanist in Brownsville had confessed to murdering Kilroy and burying his body on the beach — though under questioning, he recanted. When lawmen finally began to sort things out, the ritual killings seemed almost predestined. A map drawn two years ago by confessed mass-killer Henry Lee Lucas had predicted with inexplicable accuracy that the bodies of victims of satanic rituals would be found about where Kilroy and others were found.

The beginning of the end of the search for Kilroy was suitably bizarre. Serafin Hernandez Garcia, a nephew of the cruel and clever gangster boss Elio Hernandez Rivera, ran a routine roadblock on Sunday afternoon, April 9, and stupidly led federales to the ranch that his family used for its smuggling operations. Serafin was no towering intellect — he displayed none of the savvy that had made his uncle the leader of a gang of smugglers and pistoleros who had terrorized Matamoros and the state of Tamaulipas for years — but he was no dummy either. Yet he went through that roadblock as if he believed himself to be invisible and bulletproof.

Later that same day federales started searching the Hernandez ranch, Rancho Santa Elena. They had turned up thirty kilos of marijuana when one of them made a discovery that chilled his blood. To the unpracticed eye of a norteamericano, it appeared to be an ordinary storage shed with some melted candles, cigar butts, and empty bottles on the floor and some greasy caldrons in the yard. But the Mexican cops saw something else. They saw a devil’s temple, a place where black magic had been practiced. When they reported this astonishing news to their comandante, Juan Benitez Ayala, the investigation came to a screeching halt — much to the distress of American lawmen who believed that the smugglers knew something about the disappearance of Mark Kilroy. But Benitez was adamant: The search could not resume until the black magic had been neutralized.

Mexico has always been a country with a rich legacy of magic, born of the dynamic fusion between Christianity and ancient Indian religions. A visit to any marketplace reveals a tradition tracing back to the Aztecs — an enormous variety of strange and powerful herbs, potions, and amulets. Brujos, or shamans, work the villages, casting spells or relieving them for small fees. Even in cities as large as Matamoros ancient superstitions are a way of life; a maquiladora recently was spared being shut down only because a curandero was able to dehex a piece of expensive machinery with which a worker had been seriously injured. Magic is omnipresent; the plot of a popular mid-eighties prime-time soap opera in Mexico, El Maleficio (“The Evil One”), revolved around the premise that a wealthy businessman in Oaxaca was able to sustain power by praying nightly to Satan. Magic is also double-edged; for every evil there is a counterbalancing good. American lawmen who had visited the office of the comandante in Matamoros had noticed strings of garlic, strings of peppers, and white candles, articles commonly used in Mexico to ward off evil. It was no surprise then that Benitez called off the search until a curandero could be summoned to the ranch to cast out the demons.

After the curandero did his magic, things happened fast. On Monday afternoon a caretaker at the ranch identified a photograph of Mark Kilroy and remembered seeing him handcuffed in the back of a Suburban in the equipment yard. In an interrogation room of the Matamoros jail, Elio Hernandez Rivera, Serafin Hernandez Garcia, and two other suspects who had been arrested at the ranch confessed to kidnapping Kilroy and witnessing his ritual sacrifice. Serafin told investigators that he had buried Kilroy, and he led the way to Kilroy’s grave, which was marked by a piece of wire sticking out of the ground. The other end of the wire had been attached to Kilroy’s spinal column so that when his body decomposed members of the cult could pull out the vertebrae to make into a necklace. When Kilroy’s body was uncovered the comandante noticed that his legs had been cut off above the knees and asked Serafin if that was part of the ritual. “No,” Serafin said. “It just made him easier to bury.” Serafin had a baby face, a weak chin, and a Zapata-like mustache that seemed stuck to his face by accident. He was no peasant recently arrived on a wagon of maize; he was a spoiled suburban kid with a taste for designer jeans, tinted sunglasses, and fast American cars with cellular phones. Serafin worked at gunpoint in the hot sun for hours, digging up bodies. He seemed to resent the forced labor but was otherwise nonchalant, remorseless — curiously without passion. By midafternoon a dozen corpses lay in a row.

The story hit the wires before the last body had been exhumed. In a few hours all the major television networks and most of the major news organizations on both sides of the border had dispatched teams of journalists. Several media outlets chartered planes. Agents for Geraldo Rivera and Oprah Winfrey were on the phone. On the highway between Matamoros and Reynosa, campesinos working in the corn and wheat fields of their ejidos — communal farms — stopped and leaned on their hoe handles as jeeploads of federales raced by, closely followed by a stream of media vans and television-satellite trucks. A boy herding scrawny Mexican cattle removed his hat until the procession had passed.

Officials on both sides went out of their way to accommodate the media, effecting coverage in their own peculiar styles. U.S. Customs agent Oran Neck was crisp and to the point. Drugs caused this to happen, he emphasized. Lieutenant George Gavito of the Cameron County Sherriff’s Department was wry and laconic. When a reporter asked how the federales had gotten confessions so quickly, Gavito pointed to a bottle of mineral water — federales like to shake the bottle and squirt the water up the noses of reluctant witnesses. Press conferences were held twice daily in front of the courthouse in Brownsville, and politicians who had hurried to the Valley to assist and commiserate with the Kilroy family made their own agendas available. A Port Isabel legislator announced that he was introducing a law that would allow the killers to be tried for capital murder in Texas, even though the murders had taken place in Mexico, where there is no capital punishment. Everywhere the cameras turned — the courthouse in Brownsville, the federale headquarters in Matamoros, the killing field — there was Jim Mattox, the attorney general of Texas, his face as grave as ashes, mumbling pronouncements on the horror of it all.

The real drama was on the Mexican side, and the young comandante damn well knew it. Benitez was a new breed of federal authority in Mexico — young, educated, tough, moderately honest. He had a perfect Indian face, Bambi eyes, and a shaggy haircut, and he usually wore jeans and a Philadelphia Eagles football jacket. Mexican officials had discovered that Benitez’s predecessor and most of his top officers had squirreled away $5.5 million in cash and jewelry in confiscations and bribes. The violent border town of Matamoros was considered the end of the road for a comandante, but Benitez took to the assignment with unexpected zeal. So far the results had been spectacular: Drug busts had skyrocketed, and now he had captured practically the entire hierarchy of the infamous Hernandez gang. You could see in his eyes that the magic was working.

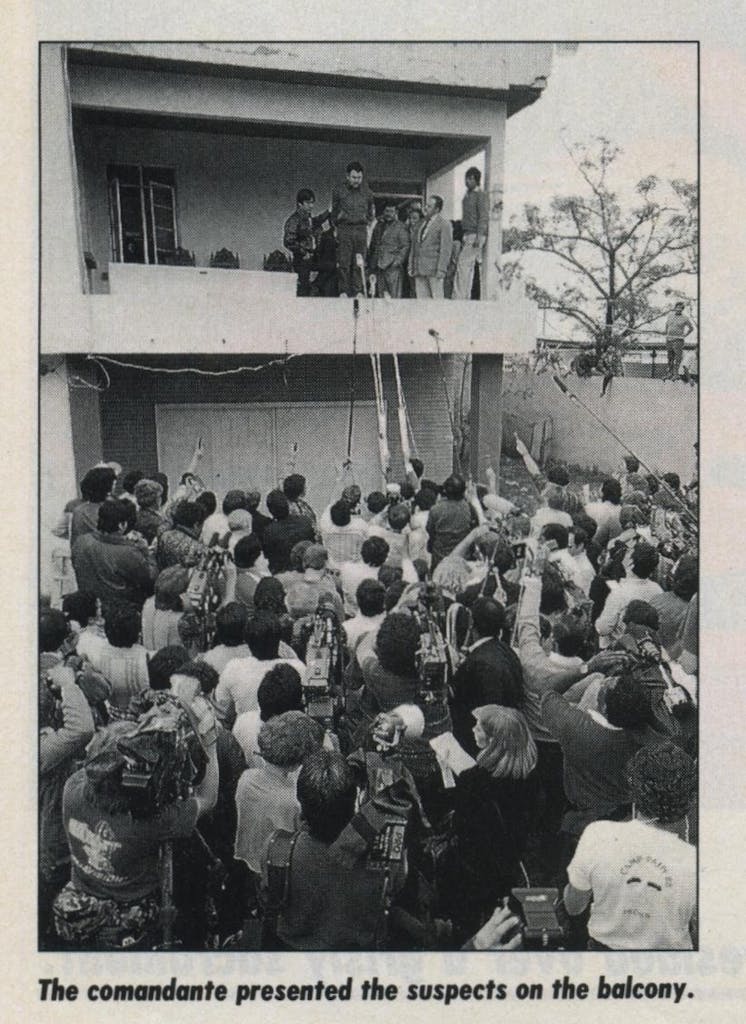

With a contingent of 250 international journalists jammed in the courtyard behind federale headquarters, the comandante appeared on the balcony with the four suspects in custody; warrants had been issued for the arrests of seven others. To the astonishment of American journalists, all four freely answered questions about their roles in the ritual murders. They seemed eager to confess. Elio Hernandez acknowledged that he had been ordained an executioner priest by the cult’s high priest and godfather, the fugitive Cuban sadomasochist Adolfo de Jesus Constanzo. Constanzo had personally executed Kilroy: Indeed, the reason Kilroy had been abducted was the Cuban’s explicit order to find an American college student for the ceremony. As TV cameras zoomed in, Elio proudly displayed the badges of his office — groups of satanic symbols branded on his arms, chest, and back. Even after two days in the Matamoros jail, Elio was undaunted. A Mexican reporter wrote that the young leader of the gang had challenged the comandante to shoot him: “Go ahead,” Hernandez had said. “Your bullets will just bounce off.”

Mexican journalists instinctively played to the morbid. From their point of view, death was far more fascinating than life. This wasn’t a story about drugs, it was a story about magic. They described in grisly detail how the Satanists cut the hearts out of victims much as the ancient Aztecs had done. Editors of even the more traditional newspapers saw nothing distasteful in running photographs of the corpses — “sin genitales,” read one caption.

Forty-eight hours after the story hit the wires, journalists were still flocking to the Valley. There wasn’t a vacant hotel room or a rent car to be had. A crew representing the Fuji network of Tokyo arrived two days late, just in time to film the most dramatic event of all — the discovery of the thirteenth body. No sooner had the Fuji crew set up its camera at Rancho Santa Elena than a truckload of federales appeared with one of the prisoners, Sergio Martinez, known within the cult as La Mariposa (the Butterfly), a pejorative term usually reserved for homosexuals.

The handcuffed Martinez led a squad of federales armed with automatic weapons to a spot just outside the corral fence. There he stopped and pointed to the ground. One of the federales handed him a shovel and a pick, and Martinez began to dig. The sun was high, and the humidity from a morning rain mixed with the unflagging stench of rotting hay and decomposed flesh that had permeated the site since the first bodies were uncovered.

Cameramen wearing surgical masks and kerchiefs over their mouths and noses moved in close, and a sound man dangled a boom mike over Martinez’s head as reporters fired questions. Martinez kept saying he didn’t kill anyone, he just kidnapped and buried them. After 45 minutes a knee and part of a foot protruded from the ground where Martinez was digging. There was a blast of putrid wind, and everyone backed away, even Martinez, who ignored the machine guns as he gagged and gasped for air. A cameraman removed his surgical mask and offered it to Martinez, who crawled back into the hole and continued digging. The body was that of a man in his thirties, blindfolded and gagged, his chest ripped open and his heart gouged out. Sin genitales.

The comandante warned the media to stay away from Martinez — which everyone took to mean “Don’t get between him and our machine guns”- but the Butterfly seemed incongruously docile and harmless. As federales removed the thirteenth body, Martinez leaned against the fence, answering questions put to him by the Spanish speaking assistant of a New York Times reporter. It was a lengthy interview, and from the emotion in the Butterfly’s voice, he might have been describing the Mexican Revolution. But the translator returned, shaking her head.

“What was that all about?” asked the Times Reporter.

“Not much,” she replied. “He just said he didn’t know why he did it.”

The comandante pandered irresistibly to the media. For example, he made no attempt to seal off the crime scene. During almost any hour of the day journalists could be found stomping about the ranch, poking in mounds of dirt and in haystacks, looking for something — anything — that no one else had found. American camera crews intentionally overlooked two tiny tennis shoes discarded near a trash pile; they suggested something too horrible for the six o’clock news. A Mexican radio station, however, broadcast a rumor that cultists were still on the prowl and looking for children to kidnap and murder, causing a number of Valley parents to take their children out of school.

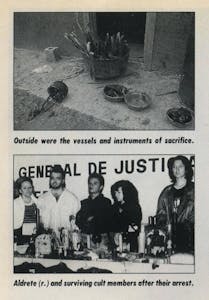

Reporters tied handkerchiefs across their faces as they stepped inside the devil’s cathedral, a small shed with a tin roof and red tar-paper walls. The air was foul and thick. On the concrete floor were the remains of an altar and the accoutrements of black magic: black candles, cigar butts, bottles of a cheap cane liquor known as aguardiente. There were also white candles, peppers, and pods of garlic used by the white magician brought in by the comandante to purify the site.

Just outside the door — apparently arranged by the federales so that the media could not miss their significance — were the vessels and instruments of the sacrificial ceremony: four caldrons and a machete. Three of the pots were small and contained chicken and goat heads, thousands of pennies, some bones, and some gold beads. The other vessel was a large iron kettle with a cluster of wooden stakes immersed in a thick, evil-smelling goo of blood and body parts, both human and animal. The iron kettle was surprisingly similar to the object described two weeks earlier by the psychic.

As the comandante related it, the ceremony went like this: First, the high priest offered up the sacrifice, cutting the victim’s throat or, as in Kilroy’s case, taking off the top of his head with a machete. The victims were usually killed first, then mutilated, though not always. Then the brains, hearts, lungs, and testicles were boiled in the iron kettle, and the resulting brew was passed among members so that they could drink and be sanctified. After that, laymen of the cult buried the remains in and around the corral behind the shed. The ultimate piety and conceit of the cult — its unforgivable stupidity — was the abiding belief that this act of unholy communion would make its members invincible.

Nothing during that whole incredible week since the bodies had been discovered was more remarkable than the show of faith demonstrated by the family of Mark Kilroy. At a press conference and later after a mass at St. Luke Catholic Church in Brownsville, the Kilroy’s spoke calmly and with deep conviction. “I don’t feel any anger at all, to be honest with you,” said James Kilroy, adding that he hoped that if and when the killers got to heaven, they would find his son and apologize. Helen Kilroy asked people to pray for her son’s murderers. Maybe the Kilroy’s would fall apart later. Maybe when they got home and started putting Mark’s things away for the last time and knew that a part of their lives was gone forever, maybe then they would cry out and surrender to the agony of their loss. But there in the Valley, in the presence of an insatiable media feeding on the details of butchery and cannibalism, the Kilroy’s demonstrated a grace under pressure that few journalists had ever witnessed.

Mark Kilroy and Bradley Moore had been talking about spring break since the start of the fall semester. At least twice a week Bradley called Mark in Austin or Mark called Bradley in Bryan, and they talked about the deeper meanings of life — beer, girls, the beach, the Miss Tanline contest, and nights across the border, in Matamoros. Mark was a junior pre-med major at the University of Texas, and Bradley was a sophomore electrical engineering major at Texas A&M. Before college, they had been basketball teammates and good buddies at Sante Fe High. Both had made the spring break scene at South Padre Island the previous year but not together.

For Bradley Moore, who had finished his exams the previous day, spring break started Friday, March 10, at noon. That was when he left his mobile home in Bryan and drove his Mustang to Austin to pick up Mark. Then they headed for Santa Fe, where they would rendezvous with two other old pals, Bill Huddleston and Brent Martin. On the way, they talked about cars and school and what they planned to do this summer. “We talked about how it would probably be our last summer at home together,” Bradley recalled.

Santa Fe is on Texas Highway 6 between Houston and Galveston. It is a small, middle-class town with wholesome, middle-class values and a large interest in high school sports. Mark, Bradley, and Brent had played basketball, and Mark and Bill had played baseball. All four boys — young men, actually — were tall, athletic, and clean-cut. None of them used drugs. All were serious students. They were the kind of boys you would like your daughter to date and maybe marry, and Santa Fe was the sort of place where you’d like your grandchildren to grow up.

Shortly after midnight that Friday, the four boys started for South Padre Island in Brent’s Cutlass, following the long Texas coastline to its end. There was heavy fog that night, and the going was slow. Counting the two times the boys stopped to eat, the journey took nine hours. It was mid-morning by the time they checked into the Sheraton on South Padre. The hotel had been fortified for spring break. All of the furniture had been removed from the lobby. The four boys from Santa Fe showered, ate, and hit the beach.

The big crowds hadn’t arrived yet. This was the opening weekend of South Padre’s five-week spring break season, and students from all over the country were beginning to pour over the bridge from Port Isabel. The island was about to become a gigantic stage on which competing forces struggled for the souls of a quarter of a million students. Beer companies were sponsoring an unprecedented variety of entertainment, including free movies, free concerts, free calls home, and surf-simulator rides. Religious organizations from as far away as Madison, Wisconsin, were handing out pamphlets and free suntan lotion and urging students to pray rather than party. A beer company offered the free use of a swimming pool to students who didn’t mind being part of a filmed commercial, and the boys took advantage of it. Mark and Bradley used a free phone line to call their parents. That night they met some girls from Purdue who were sharing an adjoining room and partied until dawn.

By Sunday the boys had more or less established a daily routine. They would hit the beach early and spend the morning soaking up rays. After lunch they would wander back to the part of the beach behind the Sheraton where the daily Miss Tanline contest was held. The cops had warned the contest sponsors about nudity, but when the emcee tried to prevent the contestants from removing their tops, the crowd went berserk. Later in the afternoon the boys would return to their room and try to take short naps, usually without success. Then they would plan their evening’s entertainment.

On Sunday night they headed for Matamoros. First, they dined at the Sonic Drive-In in Port Isabel, where they met some girls from the University of Kansas who were also on the way to Matamoros. The girls followed Brent’s Cutlass along the narrow, dangerous 24-mile highway that cuts across the tip of Texas. They parked both cars on the Brownsville side of the international bridge and walked across. They spent the whole evening at a place called Sgt. Pepper’s, then the boys and the girls went their separate ways.

Monday was another glorious day on the beach. Mark struck up a conversation with one of the contestants in the Miss Tanline contest, a coed from Southwest Texas State University. In the early evening the boys checked out a condo party that some of Mark’s former frat buddies at Tarleton State were throwing — Mark had attended TSU before transferring to UT. About ten-thirty they decided to go back to Matamoros. Again they parked on the Texas side and walked across.

That night the border town had gone mad. The full wave had hit, and 15,000 spring breakers jammed the narrow sidewalks and spilled into the streets. The nightclubs on the main tourist drag, Avenida Alvaro Obregon, had placed sandwich boards along the way, advertising specials on margaritas and beer. Once within the first block past the bridge, the boys looked for the bar with the shortest waiting line. They selected Los Sombreros, a spot with a lot of neon and music loud enough to shatter brick. They didn’t know it, but Los Sombreros wasn’t exactly your old college inn. In July 1988 the son of the owner of another nightclub had been killed in a shoot-out at Los Sombreros, supposedly by a Hernandez gang member known as El Duby. A Matamoros cop who had been following El Duby had disappeared and hadn’t been seen again. Barroom shootings were not novelties in Matamoros. Neither were people disappearing off the street. That happened every night, though usually not to gringos.

From Los Sombreros the boys wandered deeper into the madness, to the London Pub, which for the purposes of spring break had renamed itself the Hardrock Café. It was even louder and wilder than the first place, and the boys stood at the bar, dodging beer cans thrown from the balcony. Mark met some girls, and for a while the others didn’t see him. It was nearly two o’clock when Bill Huddleston suggested that they head back to the island. When Bill, Bradley, and Brent walked out of the bar, they saw Mark leaning against a Volkswagen, talking to the girl from the Miss Tanline contest.

All up and down Avenida Alvaro Obregon, people were leaving the bars, most of them heading back to the bridge, but some moving aimlessly in the other direction or ducking down side streets to smoke a joint. Making progress in any direction was like swimming in a whirlpool. Bradley and Brent had walked ahead of the other two boys and were waiting in front of Garcia’s, the gringo watering hole and gift shop, adjacent to a wooded area where vendors get their last shot at tourists crossing the bridge. Mark stopped in front of the steps of a private home to say goodbye to the girl from the Miss Tanline contest, then waited for Bill to catch up. Bill remembered Mark asking him if something was wrong. “I’m just tired,” Bill replied. “Just not in a partying mood.” Then he ran ahead and ducked behind a tree to relieve himself. When he joined Bradley and Brent in front of Garcia’s two minutes later, Mark had vanished.

The three searched for their friend until long after the bars had closed and the streets had emptied. But there wasn’t a trace. It was as though Mark Kilroy had dropped off the face of the earth.

Sitting in his pickup truck watching the spring breakers flow along Avenida Alvaro Obregon, Serafin Hernandez Garcia might have pondered the irony of his new religion, if he hadn’t needed to pee so badly — and if he were the type to ponder. Nobody had mentioned this part. Nobody had told him that one of his jobs was to kidnap people so that his uncle Elio and the Cuban could sacrifice them to the gods. The gods were insatiable. True, the Hernandez family’s marijuana smuggling business had recovered from last year’s series of misfortunes. Things had never been better on that front. Also, since embracing the Palo Mayombe religion, Serafin’s grades had improved. (He was a law enforcement major at Texas Southmost College and proud of it.) Serafin had converted to Palo Mayombe to please Elio, who was only two years older and more like a brother than an uncle. He had also done it because he thought it would bring him luck. Now it was too late to back out.

There were dozens of Hernandezes on both sides of the border — brothers, cousins, nephews, in-laws. Twenty-year-old Serafin represented the new generation: middle class, relatively well educated, conditioned to a life of plenty. For as long as he could remember, the drug business had provided. Poverty was something the old people talked about, something long before Serafin’s time. His father, Serafin Hernandez Rivera, and grandfather and most of the others had been born and raised on an ejido near the village of San Fernando, on the highway between Matamoros and Ciudad Victoria. Ejido Ramirez was as poor as they came until Saul Hernandez Rivera came up with the idea to use the ejido as a marijuana area. Ten years later they were rich. They owned ranches and villas all over Mexico, drove expensive cars, and were able to educate their children. Serafin was born in Mission, Texas, and educated at Nimitz High in Houston, where his father ran the Texas end of the family’s business. For the past seven years his family had lived in Brownsville.

Serafin Senior was the oldest of four brothers — 5 years older than Saul, 17 years older than Ovidio, and 23 years older than Elio. But Saul was the one with balls. That’s what it took to run marijuana out of Matamoros in the early eighties. U.S. drug interdiction in the Caribbean had caused traffic to be rerouted through Mexico to Texas, greatly enhancing business — and murder — in Matamoros. Dealers and second-echelon mobsters killed each other regularly, usually by way of machine-gun attacks on downtown streets. In 1984 a team of assassins in a homemade armored truck attacked a clinic where a minor mob boss named El Cacho was being treated, killing six innocents. The raid allegedly was ordered by another mob boss, El Profe, whose pistol had put El Cacho in the clinic in the first place. Though the Hernandezes were small-timers, they had the protection of a prominent and powerful Matamoros businessman who, according to reports in the newspaper El Popular, was the boss of bosses of organized crime in the border town. In July 1986 the publisher and a star reporter of El Popular were gunned down in front of their paper. The chief suspect was Saul Hernandez. Six months later Saul was cut down by machine-gun fire in front of a restaurant. His assassins were said to be drug rivals.

When Saul died, so did the moxie, skill, and connections that had made the Hernandez family successful. For the first time in memory, the family found itself bitterly divided. As the eldest brother, Serafin Senior tried to assume leadership, but he was hopeless. A month after Saul’s murder Serafin Senior was arrested in the U.S. after a bungled attempt to land a load of dope on an airstrip in Grimes County. He hasn’t yet been brought to trial, but his arrest compromised the Texas end of the business. On the Mexican side, meanwhile, Elio had seized power. Though he was the youngest of the brothers, Elio was most like Saul — ruthless, clever, ambitious, and willing to try new things. Some of the Hernandez cousins, nephews, and in-laws remained loyal to Serafin Senior, but many more fell in with Elio, including Serafin Junior and Ovidio.

Then there were other problems within the family. One of their pistoleros, El Duby, was wanted by authorities for questioning in the July 1988 shoot-out at Los Sombreros. Ovidio was feuding with a cousin, Jesus Hernandez, over a dope transaction in which Ovidio apparently pocketed $800,000 that belonged to Jesus. In the summer of 1988 a frightened Elio notified the police that Jesus had kidnapped Ovidio and Ovidio’s two-year-old son and threatened to kill him unless the money was repaid. When his loved ones were released unharmed, Elio refused to press charges.

What the family needed, Elio decided, was protection. In the world of the Hernandezes, the best protection was magic. Witches and curanderos were as much a part of their daily lives as lawyers and doctors were to, say, the Kilroy family. How a simple man like Elio hooked up with a prince of darkness like Adolfo de Jesus Constanzo is still a mystery. There are three theories, all plausible: (1) Constanzo had connections with powerful drug lords in Central Mexico and had worked with the Hernandezes on previous deals; (2) El Duby knew Constanzo through his own connections in Mexico City; (3) Elio’s girlfriend, Sara Aldrete, dabbled in black magic and had met Constanzo through friends in Mexico City’s Cuban community.

Aldrete had read books on Santeria, an Afro-Caribbean religion that relies on animal sacrifices to achieve power and punish enemies. Constanzo had grown up in a Cuban neighborhood near Miami, where the practice of Santeria was common. His mother was said to be a witch who placed hexes on neighbors and left headless chickens and goats on the doorsteps of her enemies. When Constanzo was eighteen his mother sent him to study another Afro-Caribbean religion called Palo Mayombe. But whereas practitioners of Santeria used animal parts in their rituals, practitioners of Palo Mayombe used human parts that were stolen from graves.

Elio contacted Constanzo at a luxury apartment in Mexico City that the Cuban shared with a circle of male companions. Constanzo was a shadowy, duplicitous, charismatic young man who frequented the gay bars of the city’s Zona Rosa and affected a flashy lifestyle. He was 26, older and far more sophisticated than Elio and others in the Hernandez gang. He was glib, relatively well educated, and highly persuasive. There was a Manson-esque intensity about him, an aura that was partly rehearsed, partly instinctive, and fully evil. The Cuban offered to act as the Hernandez gang’s high priest, protecting its members from all enemies and promising riches beyond their dreams — in return for a share of their drug profits.

It was less than a mile from Rancho Santa Elena to the Rio Grande. Periodically, the Hernandez gang gave thanks to the Palo Mayombe gods, then smuggled hundreds of pounds of marijuana into Texas. The Cuban apparently made up the gang’s religion as he went along, using various aspects of Santeria, Palo Mayombe, and voodoo as the mood struck him. Members of the cult smoked ritual cigars, drank ritual rum, slaughtered ritual chickens and goats, and prayed to various deities including Oshun, the god of money and sex. Constanzo insisted that his followers call him El Padrino — the Godfather — and introduced various forms of mind control in the guise of religious mumbo jumbo. As Charles Manson had used the Beatles song “Helter Skelter,” the Cuban used a movie called The Believers, in which a father and his son are caught in a web of black magic.

The tie that bound members of the Hernandez gang was drugs, not religion, but as the ceremony got stranger and their involvement got deeper, that changed. The Cuban was probably the first to suggest using human sacrifices, but it also may have been Elio or even Sara Aldrete. Of all the converts, Aldrete was the most zealous and the most mysterious.

An exceptionally tall woman with long brown hair and an athletic build, Aldrete lived an uncanny double life — honor student at Texas Southmost College by day and witch by night. Those who knew her as a cheerleader for the soccer team and a nominee for TSC’s who’s who found her courteous, friendly, and always eager to please. There was nothing to suggest her dark side. Antonio Zavaleta, who knew Aldrete well, said: “She sat in my anthropology class all semester, an A student, always present, always friendly. I never saw her wear an emblem, an amulet, a talisman, any sign of black magic — and I’m trained to watch for such things; never heard her ask a weird question, even when we talked about weird religions.” And yet Aldrete drove across the international bridge every night in her new Ford Taurus, went to her private room at her parents’ home in a middle-class Matamoros neighborhood, and prayed before a blood-splattered altar. The police believe she took part in at least one human sacrifice, that she personally selected the victim (a man who had insulted her), lured him to the ranch, and supervised a slow death that included cutting off his nipples with scissors and boiling him alive.

At first the victims were selected from the ranks of enemies — rival drug dealers or dirty cops who had gone back on an agreement — strictly business to Elio’s way of thinking. The Cuban made Elio, and later El Duby, executioner priests, branding their arms, chests, and backs with a red-hot knife. Elio was a real sweetheart of a priest. He was said to have cut out one rival’s heart while the man was still alive. The planned execution of a Matamoros cop named Sauceda produced fireworks when Sauceda pulled out a gun, and Elio had to shoot him before the ceremony began. The cop’s sudden and untimely death left the gang without a victim to sacrifice. Elio sent three of his men out to grab the first person they could find, who happened to be a fourteen-year-old boy looking for his lost goat. They threw a gunnysack over the boy’s head and took him to Elio, who promptly decapitated the boy with a machete, never bothering to look at his face. As the headless body flopped across the floor, Elio was struck by something familiar. It was the boy’s gray-and-green football jersey. Terror flooded Elio’s dark eyes as he reached for the gunnysack: He had just executed his own nephew.

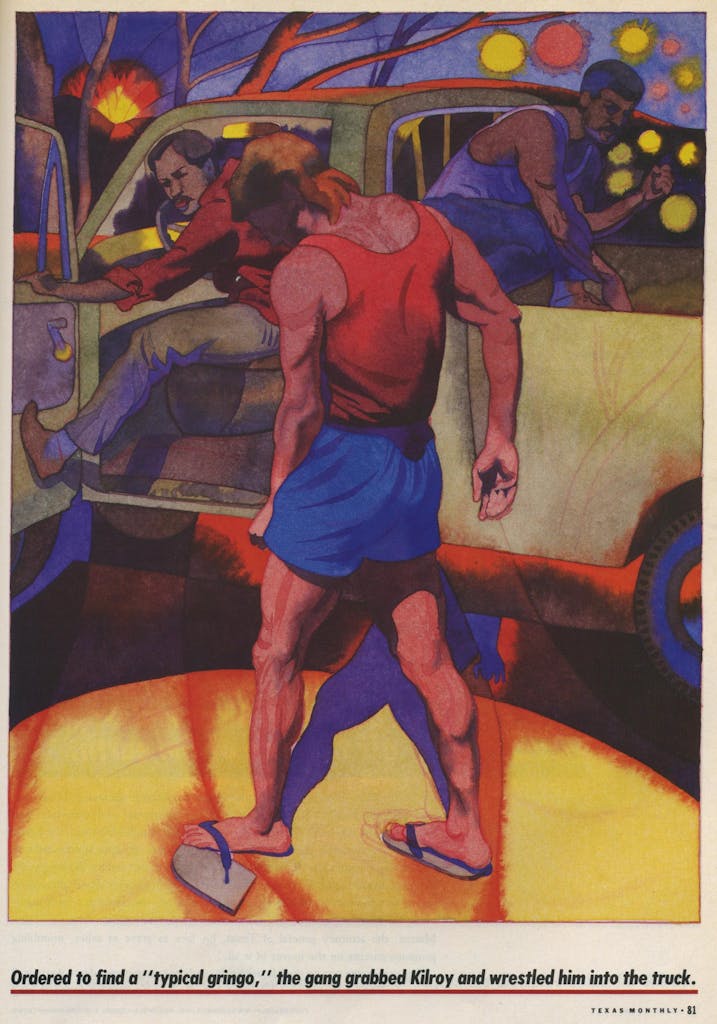

Though Mark Kilroy was selected at random, there may have been something about him that attracted Serafin Junior and his three companions. The Cuban had told them to find a typical gringo, and Kilroy’s blond good looks and wholesome manner must have been irresistible. They grabbed Kilroy and wrestled him into the pickup between Serafin and another gang member named Torres. A few blocks down the avenue, Serafin stopped to relieve himself and Kilroy escaped, but a second carload of gangsters caught the student and handcuffed him in the back seat.

They drove through the back streets of Matamoros and past an industrial district. After a while the number of small bars and vendor’s huts began to thin out and newly planted fields stretched off into the distance. The country air smelled musty and overused. There was a quarter moon, and by its light Kilroy might have had a chance to see that his kidnappers were his own age. Serafin had graduated from Nimitz in 1986, the same year Mark graduated from Santa Fe. Both of them had played baseball. They could have been on the same field, playing by the same rules.

Around a long, sloping curve, the car turned onto a narrow dirt road that snaked between two corn fields. Presently, the car’s headlights caught a barn with some farm equipment on one side and an irrigation levee on the other. The gangsters left Mark Kilroy handcuffed in the back seat of a Suburban. He didn’t see them again all night. An aging caretaker came around after dawn and gave him something to eat — some eggs, bread, and water.

Roughly twelve hours after Kilroy’s abduction, the Cuban and his disciples came for him. They wrapped duct tape over his eyes and mouth and took him across a field, his hands still cuffed behind his back. Then they guided him through the door of a shed, where the air smelled like rotting meat. It was early afternoon, the time of day when the boys would have been drifting down the beach to watch the Miss Tanline contest. Whatever was going through Mark Kilroy’s mind, whatever he imagined would be his fate, it wasn’t nearly as terrible as what was about to happen.

By Friday, the fourth day after the discovery of the bodies, the story had lost steam and dropped off page one. The Kilroys had gone home, and so had the politicians and most of the media. Nobody had claimed the $15,000 reward, though an extortionist in the Galveston County jail had tried to hit on the Kilroys for ransom. Few noticed and fewer stopped to record the activities of the peasants and campesinos who had come down from mountain villages or traveled, sometimes hundreds of miles, from their ejidos, looking for lost loved ones among the rows of mutilated corpses. They stood on the sidewalks in front of funeral homes, not sure what to do next, or in small groups at the ranch, where the search for more bodies continued.

In the shadows of the sacrificial shed, while bulldozers and backhoes excavated the putrid black soil that had been the devil’s graveyard, a priest prayed. Nearby a woman from Ejido Ramireno waited with her two sons, watching and wondering if a sixteen-year-old friend from her ejido would be among the victims. Seventy-six-year-old Hidalgo Castillo wondered the same thing about his 52-year-old son, Moises Castillo. Moises lived in Houston, but once a year he went to Ejido Morelos to work his corn fields. He had disappeared in May 1988, and in light of all that had happened, the old man feared the worst. He was right. Two days later Mexican authorities found the bodies of Moises Castillo and another man in shallow graves across the highway — victims number 14 and 15.

In the lobby on a Matamoros funeral home, Isidoro and Ericada Garcia waited while one of their daughters slipped behind a curtain to view the remains of a boy who had been decapitated and whose lungs and brain had been cut out. Devout evangelicals, the Garcias worked a farm two miles from Rancho Santa Elena. Their fourteen-year-old-son, Jose Luis, had vanished on February 25 — three weeks before Mark Kilroy had disappeared. There had been no press conferences for Jose Luis, no rewards, no attorneys general or network TV. The Garcias didn’t even have enough money to buy a body bag to bury their son, if the body behind the curtain proved to be their son.

It was Jose Luis, all right. “He had no head,” his sister reported. “It was chopped off on the side. But I knew it was him by the shirt he was wearing. It was gray and green, his favorite football shirt.”

The Garcia’s seemed almost relieved, which, strangely enough, was the same reaction the Kilroy’s had when they finally learned their sons fate. The waiting had seemed eternal. Now they were at peace. Now the white magic could do its work.

When Ericada Garcia spoke with Tom Ragan of the Brownsville Herald, it was without a trace of bitterness or irony. “If it weren’t for the Kilroy boy,” she said, “none of the other men, including my son, would ever have been found.”

Adolfo de Jesus Constanzo may have been more twisted and evil than anyone suspected. While promising to protect the Hernandez gang, he was using their connections to steal from other drug dealers. The police weren’t the only ones looking for the ill-fated gang. Constanzo had a group of followers separate and apart from the Hernandezes. It included an inner circle of Mexico City friends who may have been involved in the ritual killings of at least eight additional victims.

When Serafin Hernandez blundered past that roadblock and doomed the Matamoros sect, Constanzo suggested a vacation to Mexico City. He flew out of Brownsville the day the bodies were discovered, accompanied by Sara Aldrete, El Duby, and four or five others. When police discovered some of Aldrete’s clothing in the abandoned safe house, they assumed that she had become the newest victim of the Cuban’s murderous ritual; the so-called witch was the most expendable member of the cult. But the final twist was more demonic than even the Hernandez gang had imagined.

Three weeks later, when Mexico City police surrounded the building where the gang was hiding, the Cuban went berserk. He began firing his machine gun and tossing bundles of money out of the fourth-floor window. Constanzo had taken the precaution of ordaining El Duby and transferring to him the power to make human sacrifices; now he commanded El Duby to perform the ultimate ritual — Constanzo wanted to die with his lover and bodyguard, Martin Quintana Rodriquez. El Duby hesitated, but the Cuban slapped him and warned him that failure to carry out this last assignment would make it hard on him in hell. Constanzo sat on a stool in the closet and positioned his lover beside him, then he nodded, and El Duby squeezed the trigger of his machine gun. When police stormed the apartment a few minutes later, El Duby, Aldrete, and three others surrendered quietly.

As for the devil’s ranch where Kilroy and others were sacrificed, it remained a citadel of black magic until there was a proper purification ceremony. One quiet Sunday afternoon, when no one was looking, the federales slipped out there with a curandero. He went inside the shed, mumbled incantations, sprinkled salt on the floor, and made the sign of the cross. Then federales sloshed gasoline over the shed and burned it to the ground.

- More About:

- Longreads

- Crime

- Brownsville