This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It was summer in San Antonio and things were in their normal state of anarchy. The district attorney was a lame duck, accused of being both too hard and too soft on the police department. The police department was a shambles. The mayor was out to get the city manager, the city manager was out to get the police chief, the police chief was out to get the police officers’ union, and the union was out to get nearly everybody who didn’t wear a badge and carry a gun. There is always some blame-shifting, ax-grinding, and backstabbing going on backstage in San Antonio, but in the summer of 1986 it was spilling into the streets. Even so, the story that police officer Farrell Tucker told on that fateful Monday morning in mid-August was incredible.

Tucker told assistant chief Frank Hoyack that his best friend, Officer Stephen Smith, planned to assassinate the assistant chief and two other officials—deputy chief Robert Heuck and district attorney Sam Millsap. A few hours later, while on a semi-official undercover operation, Tucker shot and killed Smith. Why? Many a final edition may yellow with time before that question is answered, but the possibilities were rich with intrigue. Speculation ran the gamut of absurdity from simple, cold-blooded murder to a media ploy to boost circulation or even a half-baked conspiracy devised by high-level officials in which two rogue cops were supposed to solve a problem by shooting each other.

San Antonio is a city with a wild West mentality, a blood-simple alchemy, and a 24-hour attention span. Life is both cheap and eternal: that stain on the wall could be somebody’s brains, or then again it could be the Virgin Mary making one of her periodic apparitions. Over the years the media have devised a formula that plays on the public’s addiction to fresh headlines: always suggest that there is more here than meets the eye, even when there is obviously less. Today’s sensational murder becomes tomorrow’s sensational funeral and the next day’s relentless probe. News does not get old here, merely upstaged. Politicians have learned that the best way to get themselves off the front page is to leak a story about someone else.

By the time Tucker went to assistant chief Hoyack with his story of an assassination plot, rumors that a cabal of vigilantes was operating within the police department had raged for months. The rumor went public in November 1985, when the San Antonio Light published a story saying that the city manager believed that there was a killer cop on the prowl.

Though there had been a number of unsolved sniper killings and nighttime terrorist attacks, the Light story focused on a single incident, the December 1982 slaying of Bobby Folsom, a young man who was apparently burglarizing a car when he was gunned down. The killing took place in front of the apartment building where Stephen Smith’s girlfriend (and future wife), Lea, lived. One of the first spectators at the scene was Smith himself, who told investigators that he and Lea had just returned from a shopping trip. Lea supported his story. The shot was fired at night, from a distance of 75 yards, through a chain-link fence; obviously the sniper was an expert marksman. Rumors circulated that Smith had bragged to other officers that he had executed a burglar—and that his friend Farrell Tucker had gotten rid of the murder weapon for him. Police officials said that there was not enough evidence to prosecute. And that being the case, they also concluded that civil service regulations prevented them from firing Smith or even relieving him from patrol duty. Though Smith’s name wasn’t mentioned in the killer cop article, everyone at the department knew that he was the subject.

The killer cop rumor was enhanced by other revelations, the most bizarre being that some members of the elite SWAT team were sporting tattoos of twin thunderbolts—the mark used in World War II by the Nazi SS. Written beneath the thunderbolts were the words “Total Hit.” Chief Charles Rodriguez, the Southern Californian the city had hired in 1983 to reform its police department, ordered the tattoos removed, and—as was the case any time Rodriguez ordered anything—the union protested, or rather a protest was channeled through the union’s social entity and mouth organ, the San Antonio Police Officers’ Association. The thunderbolts were benign, it was said, a symbol on the order of the one used by ZZ Top. No explanation was offered for the words: presumably they referred to the SWAT softball team. Whatever the case, the chief’s order was more or less ignored.

The media had their own quarrel with the new chief, who was aloof and circumspect and unavailable except at weekly press conferences. For as long as anyone could remember, reporters had had free access to the police; before Rodriguez came, it was not uncommon to see the chief having coffee with media types. Rodriguez put a stop to that. He established an office of public information, which despite its fancy name served to shield not only the chief but also everyone else in the department from media prying. The media retaliated by publicizing the frequency with which the chief was out of town—that is to say, out of touch.

The police officers association had a separate beef with the Light, which the association believed was dwelling on the negative aspects of police work. Things got nasty when association lawyer Joe Scuro stupidly and mistakenly told some editors that the reason a certain female reporter was picking on the department was that she had been jilted by a cop.

At that point the Light started digging into the activities of the association. The series of articles that followed revealed, among other things, that the association members had started referring to each other by Mafia-type nicknames and that Scuro, known to insiders as the Godfather, was mailing intimidating letters to citizens who dared to file complaints of police misconduct.

The department’s state-of-siege mentality may have been exaggerated, but clearly some police officers were running amok. In the months after the Light’s killer cop story, members of the San Antonio Police Department were arrested and indicted on charges of brutality, burglary, drug dealing, and using their badges and guns to gain sexual favors, sometimes from citizens of their own sex. A veteran of 21 years on the force was caught kissing and fondling a male Mexican national whom he had dragged into an alley. Yet another long-running homosexual scandal involved a Bible-thumping patrolman charged with sodomizing his teenage ward, though the charges were later dropped. The situation got so ludicrous that, according to squad room humor, it would be a real relief when some cop finally got caught in the back seat of his patrol car with a woman.

But the high jinks involving police officers weren’t funny. The homes and cars of several high-ranking officers, including deputy chief Robert Heuck, were raked by gunfire. In July 1986 the home of assistant chief Frank Hoyack was firebombed. A month later an anonymous letter sent to public officials and media representatives accused chiefs Heuck and Hoyack of molesting children. From the way that the letters were addressed, using certain police department abbreviations, it was apparent that they had been written by someone inside the department.

On Monday, August 18, five days after the letters arrived, Farrell Tucker went to Hoyack with his story of an assassination plot. Hoyack was running the department because Chief Rodriguez was away on vacation—out of touch again. Most San Antonio cops thought Hoyack should have been the chief in the first place, a feeling Hoyack did not go out of his way to discourage. No doubt Rodriguez would have handled Tucker’s allegations according to the book, but Hoyack had been a San Antonio cop for 27 years and operated according to a traditional informality that made the San Antonio Police Department a virtual anachronism in major-city law enforcement circles.

An icy jolt of déjà vu must have run down Frank Hoyack’s spine as Tucker spilled out his astonishing story of Stephen Smith’s hit list. Almost everyone in the department believed that Stephen Smith was one of those responsible for the firebomb that had been thrown through the assistant chief’s garage window. Except for a fluke, Hoyack and his wife would have been killed. In his seven years on the force Smith had five black marks in his file, three for using excessive force. He was regarded as a “shooter”: Smith had shot two suspects in the line of duty, one of them dead. Other cops said that Smith carried an arsenal of unauthorized weapons in his patrol car. Smith’s most recent brutality charge had resulted in a criminal indictment and an indefinite suspension—he was fired, in other words. The incident for which he was indicted took place in August 1985, almost nine months before he was fired. It happened at South Park Mall, where Smith had disarmed and arrested a shoplifting suspect named Alfonso Perez. Though Smith had handcuffed the suspect in the back seat of his patrol car, Perez managed to escape. When Smith finally caught up with Perez, the indictment alleged, he hit him in the face. Ironically, in the view of some cops, the incident that finally cost Stephen Smith his badge was a justifiable use of force.

Tucker was no angel either. He too had five bad marks in his personnel file. True, he had never shot anyone in the line of duty, but his tight friendship with Smith made him suspect. Smith and Tucker had graduated with the same police academy class and shared many interests, including a passion for firearms. The two were among a small group of policemen and civilians who regularly armed themselves with high-powered AR-15 rifles and other weapons and conducted what they labeled strategic exercises in an isolated pecan grove in Medina County, south of the city. Following the December 1982 sniper killing of Bobby Folsom, Tucker had been questioned at length about several vigilante assaults. He was asked point-blank if he and Smith and a third, unnamed cop had a hit list. “That’s ridiculous,” Tucker had responded.

In 1984 Rodriguez ordered Tucker to undergo a psychological evaluation. The psychologists recommended that Tucker be removed from the field for six months, but somehow the recommendation never reached the chief. A year after that, Tucker was wounded when another officer’s rifle discharged accidentally; the two cops cooked up a story about a sniper to spare the other cop from being disciplined for carrying an unauthorized weapon. They finally admitted the lie, but not before a massive land and air search involving two dozen officers was under way. The chairman of the disciplinary review board, deputy chief Marion Talbert, had advised Chief Rodriguez that this was a perfect opportunity to get rid of a bad cop—meaning Tucker—and recommended that he be fired. But the chief waffled. The board’s recommendation sat on the chief’s desk for months, and Tucker ended up doing a thirty-day suspension on a lesser charge.

In light of Tucker’s record, the decisions that Hoyack made in the hours just after he heard Tucker’s tale of would-be assassination seem unorthodox, not to mention wildly improvisational. First Hoyack called the two other targets of the alleged plot, deputy chief Heuck and district attorney Millsap. The three agreed to rendezvous with Tucker at a North Side restaurant, a place where they were not likely to be seen by other policemen. There, Tucker repeated the allegations, which he had learned the previous day from Smith’s wife, Lea. The assassination plot was only part of it. Lea had told Tucker something else: Smith was the phantom sniper who had been terrorizing the city.

Smith and his wife had fought early Sunday morning, Tucker said. Smith beat Lea, and she fled to her mother’s house, where she telephoned their mutual friend, Farrell Tucker. This wasn’t the first time Tucker had been asked to intervene in their quarrels. When Tucker arrived at Lea’s mother’s house, Lea told him that she feared for her life. Then she detailed three of the shootings she had witnessed—once when Smith gunned down a man attempting to burglarize a car in front of her apartment and two other times when he used an AR-15 rifle in sniper attacks. On one occasion, Tucker remembered her saying, Smith “stalked and shot” a man in a car; the man didn’t die, but the bullet turned him into a vegetable. Smith had also blown up a van with a military-type explosive, Lea told Tucker, and now he planned to stalk and assassinate the three officials seated across the table. Tucker had made an appointment to meet Smith later that day, ostensibly to discuss his marriage difficulties.

Tucker was clearly frightened, or so it appeared to the three officials. They were frightened too; all had received death threats in recent years. Tucker worried that by the time he kept his appointment with Smith late that Monday afternoon, Smith would have learned what Lea had told him. Though Tucker was a street-tough cop and an expert marksman, he was considered no match for Smith. Cops are taught to aim for the body, Tucker remembered, but Smith always went for the head. Nevertheless, Tucker told the others that his scheduled meeting with Smith was “unavoidable,” and he volunteered to carry a concealed tape recorder and gather what evidence he could.

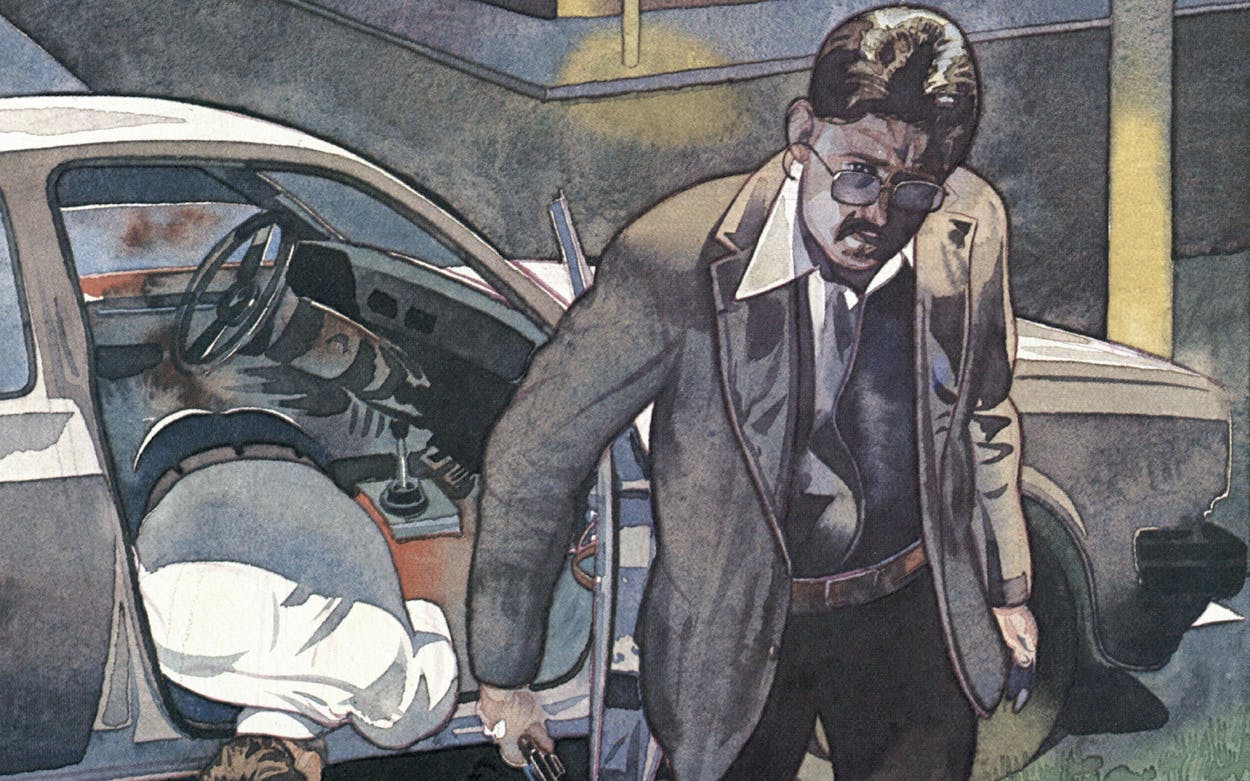

At that point, nobody was sure who to trust. But Hoyack and the others agreed that they needed more evidence, and Tucker seemed to offer their best hope. Instead of using the sophisticated recording equipment available to both the police department and the DA’s office—not to mention the FBI or other readily accessible law enforcement agencies—they decided to purchase their own small voice-activated tape recorder. Millsap volunteered to buy it—he was the only one with the purchase price, $180. Eventually, several other ranking police officers and a police psychologist were included in the plan, but when Tucker met Smith late that afternoon, there was no one else around—just the two of them in Smith’s compact car. As Tucker related events later, Smith had just pulled away from the curb when he suddenly aimed his 9mm pistol at Tucker and said, “You know, don’t you?” Smith ordered Tucker to surrender his .45. Tucker handed his uncocked weapon to Smith, who placed his own gun under the seat and trained the .45 at Tucker’s head. “I knew that he planned to kill me as soon as he cocked the gun,” Tucker told investigators. Tucker said he managed to grab a second gun, a .357 hidden in his waistband beneath the tail of his coat. Before Smith could cock and fire, Tucker blasted him at near point-blank range with five shots from his .357. The car veered out of control, jumped a curb and came to rest near the apartment complex where Smith lived.

The cop with the record for violence was dead, the cop with the record for lying was the only living witness, and San Antonio was strapped with what had to be the strangest killing in the long history of a city infamous for strange killings.

There was bound to be an orgy of blame-fixing after Stephen Smith’s death, and the vacationing chief was the perfect scapegoat. Unpopular at city hall and an object of ridicule among the police department’s rank and file, Charles Rodriguez was doomed anyway—Farrell Tucker just hurried his tenure to its inevitable conclusion. The trouble with this rationale was, everyone knew the department’s problems predated Rodriguez.

Several years before Rodriguez was hired, the city commissioned an outside consulting firm to study and identify the problems. The study cost $150,000 and recommended more than one hundred reforms, but none of them addressed the real issue: Who polices the police? According to the city charter, the city manager has that authority, but a decade of concessions and appeasements to the union has made that authority meaningless.

Since 1974, when a public referendum gave the police the right to collective bargaining, the department’s power structure has become so warped, so heterogeneous and bottom heavy that rank has nothing to do with power; the chief is, in effect, a figurehead. The dynamics have gone crazy; the government is paying the lunatics to run the asylum. This is a paradox that the insular Rodriguez seemed unable to deal with or even recognize. On most labor issues the city is rigidly conservative—when members of the garbage collectors union got too uppity, the city put the union out of business by firing its entire membership. But San Antonio is first and foremost a military town, with an ingrown martial fidelity: the military is to this city what the steel industry is to Pittsburgh. Long before Rodriguez arrived, there was a virtual wartime posture in which any politician’s failure to support the police department was tantamount to treason. “There are certain rules set down by the civil service code and the collective bargaining agreement, and we all have to live by them,” city manager Lou Fox said. “Chuck Rodriguez never understood that.”

The police association had been around for decades, so when San Antonio cops were permitted to unionize, they naturally formed around the association. In effect, the association and the union became indistinguishable, and in time so did the association and the department. “Before Rodriguez,” police association attorney Joe Scuro said, “the police officers’ association was a social group that met twice a year for a Christmas party and a summer picnic. By the time he had completed misapplying what he thought were professional management concepts, we had developed into a full-scale union.” Scuro is too modest. Though it is true that Rodriguez took a confused situation and brought it to the brink of chaos, the association already had a degree of control unprecedented among law enforcement organizations in Texas. Rodriguez’s command may have been unfortunate, but the association seldom missed an opportunity to exploit the misfortune. Even before Rodriguez arrived, the association threatened a protest strike. A few weeks later the group made a point of not inviting the new chief to its Christmas party. Members groused when he changed the radio code—simplified it, actually—and made fun of him when he redesigned the chief’s uniform and gave himself an extra star. To the cops in the squad room, Rodriguez became known as Teflon Charlie and Chuckie Chief.

Rodriguez was a stickler for form and method, a martinet but a martinet without command presence or an instinct for the jugular. He couldn’t bring himself to negotiate, nor could he intimidate his men into backing off. Previous chiefs had accepted the fact that even minor policy changes had to be negotiated with the association; otherwise, the departmental hierarchy was certain to be overwhelmed by a blitzkrieg of grievances. Some were as trivial as who got to take a police car home after work, but trivial or not, the grievances had a paralytic effect on the department: on 35 occasions since the collective bargaining agreement, members of the association filed grievances to halt policy changes with which they disagreed, and on 25 of those occasions they won. Some of the grievances, on the other hand, attacked the fundamentals of command. The chief wasn’t able to transfer cops who performed poorly, even in critical positions, nor did he or any of his senior officers have a voice in promotions. Attempts to dilute the association’s influence—appointing a single nonvoting civilian to the nine-member police disciplinary review board, for example—were crushed in the bud. Sammy Miller, who worked ten years for the police department before becoming a private investigator, explained, “The idea of having a civilian on the review board is considered communistic.”

When the chief wasn’t butting heads with the association, he was crashing against the impregnable civil service code. The civil service commission invariably overturned the department’s own review board rulings. In the two years after Rodriguez was made chief, for example, eight of the nine cops who had been judged guilty of abuse of force and suspended got their judgments reversed by the commission. Particularly offensive to Rodriguez was the so-called 180-day rule, a civil service regulation that prohibited the department from punishing an officer more than six months after an infraction—except in certain clearly defined criminal matters in which suspension was automatic anyway. This rule also prevented the chief from fully considering an officer’s past record when determining the punishment for a particular act of misconduct or from establishing a pattern of misconduct over a period of time. In the case of Stephen Smith, for example—and maybe Tucker too—a pattern of misconduct was more pertinent than any single act.

When Fox hired Rodriguez in November 1983, he recognized that bringing in an outsider was a calculated risk, especially an outsider who was also Hispanic. The city had never had a Hispanic chief: there was an inviolable tradition that the department be commanded by an Anglo who had come up through the ranks. Tradition was part of the overall problem. “There was a lot of inbreeding of attitudes, a lot of hidebound practices that wouldn’t be easy to give up,” Fox said. “The police association had made great inroads and had considerable influence with the city council.” Rodriguez had the precise qualities Fox sought: thirty years with a major city law enforcement agency—the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department—a master’s degree in public administration, a Spanish surname, and fluency in the Spanish language; what was more, he had experience in the area of community relations. Fox apparently didn’t stop to consider that the community with which Rodriguez had relations was a thousand—it might as well have been a million—miles from San Antonio.

From the start, Rodriguez came across as high-handed and arrogant, a man who gave the appearance that he would be taking the first plane back to civilization as soon as he had instructed the natives in the rudimentary elements of hygiene. At his first roll call, Rodriguez advised the assembled cops that they were at least ten years behind law enforcement agencies in Los Angeles. This was true, of course, but cops in San Antonio resented the way Rodriguez seemed to go out of his way to throw L.A. superiority in their faces. “He wouldn’t listen to what you were telling him,” recalled Sergeant Jimmy Willborn. “You’d be explaining some technique or procedure, and you’d see him staring off in space, then he’d interrupt and say, ‘When I was in Los Angeles. . .’ ” Every previous chief had been a member of the association, but that wasn’t Rodriguez’s style. In his view, no officer in a supervisory position had any business belonging to the association. “It seems to be a conflict of interest,” he said. “How can you make a decision for management when you have a stake in the other side?” He placed great emphasis on chain of command and considered it improper for the chief to be represented by an association president who was only a sergeant.

The sergeant in this case was Harold Flammia, a headstrong, quick-tempered, fiercely proud Italian American, dubbed “THE .44-CALIBER MOUTHPIECE” by one headline writer. Flammia, who was elevated from association treasurer to president midway through Rodriguez’s administration, seemed predestined to play the role of a street cop’s street cop. A year before Rodriguez arrived, Flammia shot and killed a burglary suspect, but in the exchange he was critically wounded. For weeks he lingered near death. He underwent twelve operations and was twice administered last rites. When Flammia recovered, he sued one of his doctors for malpractice and collected a large settlement, something in the half-million-dollar range. Under state law the city was entitled to claim a part of the settlement, but when it tried there was such a protest from the association that the claim was withdrawn. Flammia had not only emerged from his ordeal a hero; he also had the financial independence to speak his mind, which he did at every opportunity.

There were racial and sexist overtones in some of Flammia’s more vitriolic attacks. The sergeant was particularly scornful when Rodriguez jumped the department’s highest-ranking black officer, James Robinson, from captain to the newly created position of assistant chief. A veteran with 21 years on the force, Robinson is one of 55 blacks in the 1317-man department (the city’s black population is only 7 per cent) and the only black cop with a rank above sergeant. Flammia accused Rodriguez and Robinson of trying to bust the union by fostering splinter groups composed of Hispanics, blacks, and women, a charge stoutly denied by both. “Flammia doesn’t give those minority groups much credit for intelligence,” Robinson said. “They came together, without any encouragement fromf anyone, because they had a common cause.” Two of the three splinter groups were formed before Rodriguez arrived, and—as Rodriguez pointed out—membership in any of those minority groups required membership in the association.

One of Robinson’s jobs was to oversee the police academy, and members of the association were outraged when entrance standards were lowered or, in some categories, abandoned. As in most police academies, there is no longer a height requirement; one recent academy class became known as the Smurfs. “When I pointed out to the chief that we had just graduated a woman who was four foot nine and weighed less than a hundred pounds,” Flammia said, “he told me size makes no difference, anyone is trainable. We had one woman wash out of the academy because she was too weak to pull the trigger. Robinson wants the standards lowered so he can hire more minorities, so he can look good, so he can be chief some day.” According to Rodriguez, height requirements are irrelevant, as well as illegal. “If it were up to Flammia, everyone would be five foot eight, or whatever Flammia is,” Rodriguez responded. “Flammia wants the old macho type they had twenty years ago, where they rush in and manhandle every situation. We want our officers to use procedure and technique, not bulk and brawn.”

Much of Flammia’s criticism appeared in the pages of the police association magazine, the Centurion, where in the Mafia lexicon Flammia was known as Loco Brazi. Flammia writes and edits most of the articles and uses his own column to deliver screeds outlining his general philosophy. Sample: “If you take all the bleeding heart reform minded liberals and put them in one group, they collectively wouldn’t make a pimple on John Wayne’s ass!!! (Rest his soul).” One Centurion item went after the local founder of Mothers Against Drunk Drivers, who happened to be the wife of a veteran robbery detective. When the detective complained, a subsequent item hinted that a certain robbery detective better watch out or he might find himself sleeping with the fishes. Flammia and association attorney Joe Scuro insisted that all the Mafia talk was meant as a joke, but some police officers took it seriously enough to threaten to resign from the association.

Flammia had several face-to-face altercations with the new chief, but the one that ultimately broke off relations between the two men came in 1984 after a rash of police shoot-outs. At roll call one day Flammia told his squad, “I’ve attended my last police funeral. Your first duty is to protect yourselves and others. You can’t stop and worry about the consequences.” Though this statement seems not unreasonable, a reporter who happened to be there at the time wrote that in effect, Flammia was telling his men to shoot first and ask questions later. Rodriguez ordered Flammia to his office. According to a witness, the dialogue quickly degenerated into an exchange of personal insults.

The chief and the sergeant stopped speaking after that, but the inevitable collision course accelerated. In late 1985 and early 1986—attorney Joe Scuro calls it Rodriguez’s “purge period”—the chief suspended 22 officers. All but one of the suspensions were overturned by the civil service commission. Though the review board had already determined that the complaint against Stephen Smith for beating suspected shoplifter Alfonso Perez in the South Park Mall parking lot was valid—and had recommended that he be fired—Smith was not one of those suspended.

In disciplinary matters Rodriguez ran hot and cold. The chief dismissed a cadet for using an unloaded pistol while rescuing an elderly woman from a mugger—cadets are not authorized to carry weapons, even unloaded ones—but he refused to fire Milton Barrera, the veteran cop who had been charged with sodomizing his teenage ward. When a situation called for a strong hand, Rodriguez’s response was often curiously mild. He blamed the civil service commission for the inept way that the Stephen Smith affair was handled and pointed out that he inherited this problem from the previous administration. Even though the evidence that Smith had gunned down Bobby Folsom in front of Lea’s apartment was circumstantial, Rodriguez had another opportunity to fire Smith in January 1984, when the review board determined that Smith had beaten a prisoner who was handcuffed and strapped in the back of a patrol car. Instead, Rodriguez let him off with a three-day suspension. Again, in August 1985, the review board upheld the brutality complaint against Smith for smashing the face of Alfonso Perez, but again the chief vacillated, allowing the 180-day statute of limitations to expire.

Despite Rodriguez’s standard complaint that the civil service code had him hogtied, there appear to be ample reasons clearly stated in the code to suspend an officer under the circumstances. It doesn’t take a grand jury indictment to fire a cop. Among other reasons, the department can dismiss a police officer “whose conduct (is) prejudicial to good order” or who violates “any rules and regulations of . . . the Police Department.” Maybe the civil service commission would have overturned a suspension or maybe not; Rodriguez did not elect to find out.

That didn’t prevent district attorney Sam Millsap from recommending Smith’s criminal prosecution. The indictment came down in the spring of 1986, during the heat of an election campaign, and Millsap’s opposition—Sergeant Harold Flammia included—blasted the incumbent for what many perceived to be excessively harsh treatment of police officers. During that same period, ironically, Millsap dismissed the sodomy case against patrolman Barrera. Attempting to prosecute Smith is not what cost Millsap the election, but it is what almost cost him his life.

Nobody seemed to notice at the time, but there was a pattern between Stephen Smith’s problems with the department and a string of unsolved vigilante attacks. Shortly after the Perez beating—and the complaint that eventually cost Smith his badge—the home of a Hispanic family who had befriended Perez was riddled by gunfire. There had been an almost identical incident the previous January, three months after another suspect charged Smith with brutality. And in 1983 the home of a public utilities service worker who had turned in Lea Smith for sleeping on the job was attacked at night by two gunmen. Each of the attacks on the homes and cars of ranking police officers followed incidents in which Smith had been disciplined.

Except for Flammia’s criticism of the district attorney, the police association remained abnormally silent on the Stephen Smith affair. A few weeks after Smith was killed, however, Flammia called a press conference and blasted the department for not firing Smith—or at least taking him off the street—back in 1982, when Bobby Folsom was gunned down. If that had happened, of course, the police association would have screamed bloody murder.

Chief Rodriguez wasn’t the only one on vacation the week Smith was killed. City manager Lou Fox, a handsome, trendy, wisecracking bachelor whose lifestyle revolved around jogging and attending consciousness-raising seminars, was in Mexico. He was sharing a condominium with the ex-wife of one of his assistant city managers—as readers of Paul Thompson’s column in the Express News learned that Sunday morning, the same morning that Lea Smith supposedly told her dirty secret to Farrell Tucker. Fox was already in hot water with the mayor and the city council. Henry Cisneros had adopted a puritanical view of Fox’s relationship with an assistant’s ex-wife. According to Thompson, Cisneros had extracted a promise from Fox that the affair would end and had been assured that it was over. “What I made clear to Lou was that he had to shape up or ship out,” the mayor was quoted as saying. “I was very explicit.” When Cisneros made this remark, he had no idea that Fox and the woman were, at that very moment, vacationing together in Mexico. Like others in San Antonio, the mayor read it first in Thompson’s column.

Getting clipped by Paul Thompson is no small matter in San Antonio. Nowhere else in Texas, or anywhere else so far as I am aware, do newspapers exercise so much clout—they don’t merely report the news, they frequently create it. In this respect, no one has more muscle than Paul Thompson. For thirty years Thompson has cranked out one of those gossipy, self-righteous, guardian-of-the-people columns that used to pass for investigative reporting. Most such columns died off in the sixties, but Thompson’s endures like a rusty sword in the hands of a contemptuous minor deity. Six days a week he rails against potholes, uncollected garbage, bans on smoking, women’s rights, and—to use Thompson’s own description of Lou Fox—“a flip sophisticate with faddist leanings.” When an aide telephoned Fox and read him that column, the city manager grabbed the first plane home.

That Monday, while events within the police department were speeding Stephen Smith toward his rendezvous with death, Fox was in executive session with the city council, fighting for his job. The mayor was carrying on about “a mini-Peyton Place,” and council members were seriously wondering if Fox possessed the good judgment to continue managing the tenth-largest city in the country. Fox heard nothing about the assassination allegations until late that evening, when Hoyack telephoned and told him about the shooting. The city manager had known about Stephen Smith since the sniper murder in December 1982, and subsequently he had learned some things about Tucker. It had crossed Fox’s mind that he might someday be the victim of a crazed sniper, and he had asked to see photographs of both Smith and Tucker, in case it became prudent to recognize them in a crowd.

When the full impact of what had happened registered, Fox recalled, it was “almost like serendipity.” In the seven days that followed, Fox once again established that he was a first-rate crisis manager. After assuring the city council that there was no reason to believe Tucker wasn’t telling the truth, he asked for and received Rodriguez’s resignation and named Hoyack acting chief, even though Hoyack was sure to be part of the investigation. The mayor made public his own belief that San Antonio had barely averted the sort of massacre that had put the small town of Edmond, Oklahoma, on the map the same week. Critics may argue that what Lou Fox saw as serendipity only served to compound San Antonio’s embarrassment, but one thing is certain: Fox got his personal life off page one.

Farrell Tucker had become a hero, at least in the public mind. A lot of cops had their doubts; they wondered if Tucker wasn’t just a cold-blooded, albeit extremely cunning, killer. Nobody in the department knew much about Tucker, except that he was Smith’s best friend. Both had been MPs in the army. Tucker had seen combat in Vietnam and claimed to have worked as a special agent for Army intelligence. Tucker was four years older than Smith, more confident and outgoing; Smith tended to look on Tucker as an older brother. They were both products of white middle-class upbringing—Tucker from a small town in Arkansas and Smith from Terrell Hills, one of San Antonio’s premier silk-stocking neighborhoods.

Though both were dedicated street cops, neither was well liked within the department. They weren’t company men. They were loners who operated outside the brotherhood. This didn’t mean that the brotherhood wouldn’t support them—they were still cops, that was the bottom line. Chief Rodriguez had complained that there was “a code of silence” in which good cops instinctively sheltered bad cops. Sergeant Flammia laughed at this notion, but testimony developed by the grand jury supported it. Whether the silence was motivated by brotherhood or just fear of retaliation, the rumors were apparently true: Smith had bragged about his vigilante activities to other cops, and he had implicated Tucker in at least a few of the crimes.

But there was always a lot of loose talk among cops. It was a way of blowing off steam. Stress went with the territory. Smith and Tucker patrolled the redneck dives and dark alleys of San Antonio’s tough South Side, and they did it by choice. Working high-crime areas shatters idealism, erodes perspective, warps reality. There was a minor incident in which Tucker shot some dogs that were allegedly threatening children; he became a hero in the neighborhood, but other cops wondered if he wasn’t losing control. “Tucker developed a mind-set that it was a jungle out there, that it was us against them,” said deputy chief Marion Talbert, Tucker’s commander. So did Smith. So do a lot of cops. What seems like excessive force to a review board—not to mention to the media or the public at large—can mean survival to the cop on the scene. That’s why, as former patrolman Sammy Miller says, having a civilian passing judgment seems, in some perverse way, totalitarian.

Many reporters knew Smith and liked him. Smith was good-humored and unfailingly courteous, so frail and slender that it was somehow comic to see him walking beside Lea, who was six foot four and worked as a laborer for the public utilities system. Tucker looked only marginally tougher, a rotund figure with short, stout arms, a baby face, and the pouting mouth of a school-yard bully. There was something disarming, even likable about Smith’s self-effacing manner. When he was accused of hitting a suspect with the butt on his pistol, Smith joked with reporters, “You know that’s not the end of the pistol I use.” KSAT-TV’s Mary Walker had interviewed Smith in 1982, not long after Smith had gunned down a shotgun-wielding robber in front of a fried-chicken franchise. There is a poignant moment in the interview when Walker reminds Smith that he shot the suspect five times and Smith replies in a tone of boyish innocence: “He didn’t go down until the last shot.”

Richard and Lillian Smith, Stephen’s parents, never liked the idea of their son’s being a cop, though Stephen had never wanted to be anything else. “He wanted to change the system, to right wrong,” Lillian said as we talked one evening in the dining room of their sprawling Spanish-style home in Terrell Hills. “He was always for the underdog.” Stephen’s sister was crippled, and so was his best friend at Alamo Heights High; Lillian recalled her son’s patience and compassion in dealing with them. Stephen had a need to belong, to be a part of something. He wasn’t talented enough to play football, so he served two years as student manager of his high school team, meaning he got to wash jockstraps and tape ankles. Classmates remembered him as a shy, polite boy who kept to himself but was gushy, almost puppylike, with anyone who paid him attention. He was religious and had read the Bible from cover to cover—later, after he joined the force, his religious inclination took on what one friend called “an Old Testament ferocity.” Lillian fought back tears as she talked about her son and the incredible set of events that permanently altered their lives. This wasn’t the sort of thing that happened to families in Terrell Hills.

When Richard Smith thought about Farrell Tucker’s version of his son’s being killed— and he thought about it constantly—his face reddened with rage and frustration. He hadn’t talked to Tucker, except when Farrell called and asked the family’s permission to attend the funeral. Richard Smith still couldn’t believe Tucker had had the gall to ask to attend the funeral, or that he had consented.

Already the newspapers were speculating what Richard Smith knew in his heart: his son was murdered. “Assassinated” would be more accurate. The medical examiner was telling the grand jury that almost all the physical evidence disproved Farrell Tucker’s account of the shooting. It would have been almost impossible for Smith to have been looking at Tucker when he was killed, for example. More important, the lack of blood on the .45 and gunpowder residue found on Smith’s right palm suggested he was unarmed and probably grasping for the .357 when Tucker blew him away. Richard Smith took another sip of his Scotch and said in a barely controlled rage: “Two deputy chiefs, paper shufflers who haven’t been on the streets in twenty years, playing gumshoe. No backup. A cheap tape recorder. Then Farrell shoots my son five times in the back or side of the head. I’ll guarantee you this: if you shot my son one time, the other shots would be in the front because he’d be coming at you.”

The autopsy showed that only the first two shots hit Stephen Smith in the side of the head, killing him instantly. He was already dead before three additional slugs passed through his right arm and abdomen. The point was, hardly any of Tucker’s account made sense. If Smith had intended to kill Tucker, why was Smith driving? Why didn’t he disarm Tucker before they got in the car? By Tucker’s version, Smith was simultaneously steering, shifting gears, taking Tucker’s .45, and placing his own 9mm under the front seat, all the while keeping a gun trained on Tucker’s head. Surely an expert marksman like Stephen Smith could have cocked and fired the .45 before Tucker had time to retrieve his backup weapon. “Tucker always carried a second gun, and Stephen damn well knew it,” Richard Smith said.

After the shooting, police searched Smith’s apartment and turned up an arsenal of weapons—seventeen handguns, six rifles, five shotguns, 50,000 rounds of ammunition, and two homemade bombs. A subsequent ballistics test on one of the rifles, an AR-15, established that it had been used in two unsolved and apparently unrelated sniper slayings in the spring and summer of 1985; as far as police could determine, neither victim had ever had any encounter with Stephen Smith. A second search of Smith’s apartment—this one by the FBI, which was conducting a separate investigation—shed light on Stephen Smith’s taste in books. Most of the books had been ordered from Soldier of Fortune magazine, and they included such intriguing titles as The Shotgun in Combat, Dead or Alive, They Shoot to Kill, The Revenge Book, Son of Sam, and a particularly vile little volume suggesting ways to punish enemies, Techniques of Harassment.

The scope of the grand jury investigation was limited to a single issue: Was Tucker justified in killing Smith? Unfortunately, the thirty-minute cassette in the voice-activated tape recorder had run out before Tucker even got in the car with Smith. The medical examiner’s report was solid evidence that Tucker was lying, but then Tucker was the target of this investigation, not the key witness. One key witness was Lea Smith, and she refused to talk unless she was granted immunity from prosecution. San Antonio attorney Sid Harle, a former assistant DA who was appointed special prosecutor, could go along with some degree of immunity if it meant widening the net of the investigation. After all, if Lea knew about her husband’s vigilante raids, then she also knew who else was involved. “As it turned out,” Harle said later, “it wasn’t that simple. Under Texas law we needed a corroborating witness.” In the end, Harle was forced to grant partial immunity not only to Lea Smith but also to her husband’s closest civilian companion, a former Army Ranger and Black Beret weapons expert named Bill Brown.

Brown confirmed that Smith was indeed the phantom gunman who had terrorized San Antonio for the past four years. “He talked a lot about his God-given right to do the things he was doing, that God actually told him to do those things,” Brown told me several hours after he had testified before the grand jury. Brown was prohibited by orders from the grand jury from spelling out exactly what God had instructed Stephen Smith to do, but it was obviously something terrible. Brown, a music major at San Antonio College and the son of the former superintendent of schools in Atascosa County, was among the small cabal of gun nuts and midnight crusaders who ran with Smith. All were civilians, and the group included Clyde Skeen, a gunsmith, and Richard Redwine, a former reserve deputy with the Bexar County Sheriff’s Department. Though Brown had met Farrell Tucker on several occasions, most of what he knew about Tucker came from Smith. The former Black Beret didn’t say exactly what Smith told him about Tucker, but he did tell me: “Those are the two most dangerous guys I’ve ever met.”

After seven weeks of testimony, the grand jury indicted Farrell Tucker for murder. Skeen was indicted for lying to the police about a shotgun Smith had checked out of the police property room—police think it was the gun used in the attack on the home of deputy chief Heuck, but the ballistics evidence in that particular case has been misplaced. Redwine was charged with taking part in the shotgun attack of a van owned by a former Internal Affairs officer. The grand jury found no evidence that any police officer except Smith took part in the raids; all of the testimony linking Tucker is hearsay and inadmissible. Smith may have exaggerated Tucker’s role in the attacks—or he may have lied about them completely—but if Tucker knew anything at all about his best friend’s secret life, it was enough to end his career as a police officer. He must have at least sensed that Smith was cracking up. He could have known, for instance, about the anonymous letter accusing their superiors of molesting children: copies of the letter were found in the rear seat of Smith’s car, in plain sight. Was Tucker a patsy? Was he stupid? Was he crazy? Was he crazy like a fox? Was Tucker, as special prosecutor Sid Harle seems to believe, a diabolically clever killer who hatched a plot in which two high-ranking cops and the district attorney serve as his alibi witnesses? A jury will decide what happened, but no one except Farrell Tucker may ever know for sure.

The grand jury’s decision poses more questions than it answers. When reporters asked Harle if the grand jury report exonerated Chief Hoyack and the others, he replied, “They used extremely poor judgment, but they are not necessarily subject to criminal prosecution.” Harle paused for a moment, then added, “However, I encourage further investigation. The federal government or another grand jury or somebody needs to look into the way the San Antonio Police Department has been run for at least the last five years.”

The reaction at city hall was in character. Everyone scrambled to get on the right side of the inevitable power struggle. The mayor, who had been a strong supporter of deputy chief Hoyack a month earlier, was now demanding that Hoyack step down. City manager Lou Fox, the only one with the power to force Hoyack to step down, refused. Councilman Jimmy Hasslocher, who sided with Fox, told reporters that an incident like the Smith murder “builds character” and therefore Hoyack was almost indispensable. Councilwoman Helen Dutmer argued that the police department didn’t have any problems in the first place, until somebody got the notion to reform it. A week later Hoyack resigned, stalling but not terminating the showdown between the mayor and the city manager.

Paul Thompson wrote that Fox had “allegedly leaked” a story to the Light, saying he had ordered Rodriguez to fire Farrell Tucker eighteen months ago, when he read the psychologist’s letter urging that Tucker be taken off the street. An admission that Fox knew about this letter could be an open invitation to lawsuits, some of which were already being contemplated against the city. Rodriguez denied that Fox had ever told him to fire Tucker, and Fox responded by threatening to cut off the ex-chief’s $6000-a-month severance pay if he didn’t put a lid on his public utterances. The only sure winner in all this is the San Antonio Police Officers’ Association, which apparently managed to keep its skirts clean during the whole sordid affair. Maybe there are other Smiths and other Tuckers in the ranks, maybe not; if the city is lucky, it will never have to find out. In the meantime, a new contract is being negotiated, which will almost certainly improve the association’s position. Sergeant Flammia, for example, has asked to be freed from his normal patrol duties and paid by the department to run the association full time. Flammia maintains he doesn’t care who the new chief is, as long as he has the backbone to rid the department of its bad apples and stand up for what is right.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Police

- Longreads

- San Antonio