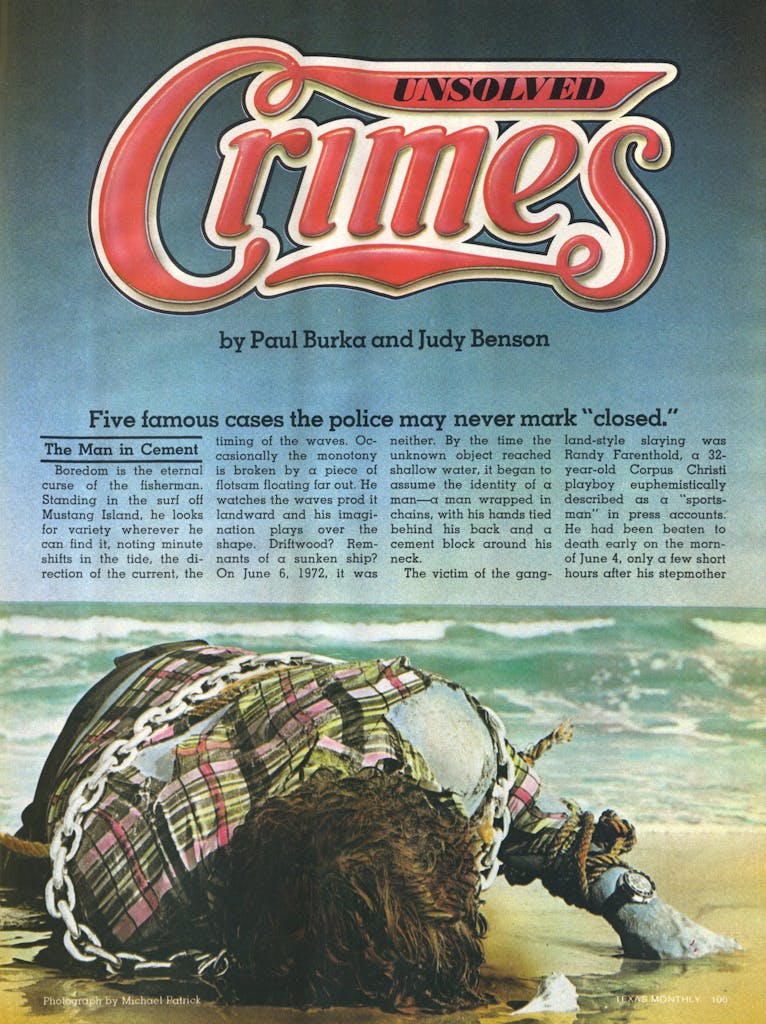

The Man in Cement

Boredom is the eternal curse of the fisherman. Standing in the surf off Mustang Island, he looks for variety wherever he can find it, noting minute shifts in the tide, the direction of the current, the timing of the waves. Occasionally the monotony is broken by a piece of flotsam floating far out. He watches the waves prod it landward and his imagination plays over the shape. Driftwood? Remnants of a sunken ship? On June 6, 1972, it was neither. By the time the unknown object reached shallow water, it began to assume the identity of a man—a man wrapped in chains, with his hands tied behind his back and a cement block around his neck.

The victim of the gangland-style slaying was Randy Farenthold, a 32- year-old Corpus Christi playboy euphemistically described as a “sportsman” in press accounts. He had been beaten to death early on the morn- of June 4, only a few short hours after his stepmother Sissy had lost her first bid for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination to Dolph Briscoe.

Possible motives for the crime were numerous. Robbery certainly had to be considered; there was no money on the corpse, but there was an expensive waterproof wristwatch. (It was still working.) Or Farenthold, who was known to gamble for high stakes, might have been killed because he failed to cover his tosses. But he had a good reputation for paying his gambling debts. A third possibility caught the attention of the FBI, which entered the case to investigate a possible obstruction of justice. Farenthold had filed a complaint against four men subsequently indicted for conspiracy to defraud him of $100,000.

The indictment alleges that the four men—two from Corpus Christi, two from Louisville, Kentucky—arranged, for Randy to buy Mafia skim money at a discount. The transaction, according to the indictment, was to have taken place in a Houston motel room, but just as the exchange was about to begin, the group was held up and robbed by a menaced man brandishing a shotgun. Too late, Farenthold decided that he’d been conned and went to the police. Since the case against the men depended on his testimony, charges had to be dismissed after his death. But police believe that other parties unknown could have had a motive, too—someone who arranged the contact, perhaps, or helped finance Farenthold’s part of the deal and didn’t want his role exposed in court.

Sheriff’s deputies thought they were on the right track a month after the murder when they found a car with hair and traces of blood similar to Farenthold’s in the trunk. Almost four years later, they’re still looking for the driver.

The Ladies Who Danced With Death

The one overwhelming fact of life is chance. Once Hazel Frome and her daughter Nancy had decided to drive from San Francisco to Parris Island, South Carolina, they might have chosen the northern transcontinental route instead of the southern road through El Paso—but they didn’t. Or their Packard might not have developed a noise in the motor just before they reached the Texas border city—but it did. The local Packard garage might have had the necessary parts to repair the car—but it had to order them and wait five days instead. And Nancy and her mother might be alive today—but they aren’t. It took one last cruel act of chance—the wrong meeting with the wrong person in the wrong place at the wrong time—to produce a double torture-murder case that 38 years later remains in the Department of Public Safety’s files, unsolved.

Hazel, 46, and Nancy, 23, left their car on the afternoon of March 25, 1938, and requested that it be ready at 6 a.m. the next day. That night—after all, it was only one night—the socially prominent women did something a little out of character; they went to Juarez and lived it up. They were seen dancing with an unknown American in a Mexican cabaret. When they returned to the hotel shortly before midnight, they got the bad news about the car, and for the next four days, they shopped in the Juarez marketplace and danced away the nights.

Four days after they finally left El Paso, a county sheriff found them, dead and mutilated, in the desolate wasteland six miles east of Van Horn and half a mile south of U.S. 80. Both women had been savagely beaten and choked; in addition, a large piece of flesh had been bitten from Mrs. Frome’s arm and Nancy’s body was marred by cigarette burns. Both women had been shot—but by different guns. They were partially undressed but had not been raped. Valuable jewelry had been ignored. There was, in short, no apparent motive.

There were, however, plenty of clues. The Packard was found abandoned 56 miles east of the spot where the bodies were discovered. The car’s spare tire had no inner tube; perhaps the Fromes had stopped to fix a flat tire, only to encounter a not-so-good Samaritan. An El Paso truck driver reported seeing a black sedan following the Packard early on the afternoon of the murders; several hours later the two cars passed him going the opposite direction, followed closely by a third car with mysterious markings on the side. A vehicle with a similar insignia had been used by narcotics smugglers, leading police to speculate that the Fromes may have been mistaken for dope runners who double-crossed their ringleaders. Police interrogated more than 3000 persons, from highway travelers to narcotics addicts, all to no avail.

It is a different world now. Packard stopped making automobiles in 1958, and garages willing to repair cars overnight vanished long ago. The Cortez Hotel, where Hazel and Nancy Frome spent their last five nights, booked its final guest in 1970; it has been converted into a Job Corps center. Even the desert itself is different, a victim of the encroaching city and land developers. As for the police, they too have changed. Once confident of solving the case, they have lost their optimism with the years. As late as 1965, Department of Public Safety Director Homer Garrison could say, “I think there’s a good possibility this case will still be solved someday.” If it is, Garrison won’t be around to see it. He died in 1968—30 years after Hazel and Nancy Frome.

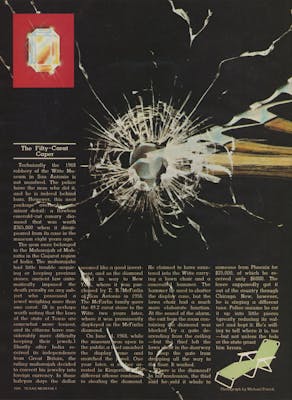

The Fifty-Carat Caper

Technically the 1968 robbery of the Witte Museum in San Antonio is not unsolved. The police have the man who did it, and he is indeed behind bars. However, this neat package overlooks one minor detail: a flawless emerald-cut canary diamond that was worth $365,000 when it disappeared from its case in the museum eight years ago.

The gem once belonged to the Maharajah of Mahratta in the Gujarat region of India. The maharajahs had little trouble acquiring or keeping precious stones, ancient law automatically imposed the death penalty on any subject who possessed a jewel weighing more than one carat. (It is perhaps worth noting that the laws of the state of Texas are somewhat more lenient, and its citizens have considerably more difficulty keeping their jewels.) Shortly after India received its independence from Great Britain, the ruling maharajah decided to convert his jewelry into foreign currency. In those halcyon days the dollar seemed like a good investment, and so the diamond found its way to New York, where it was purchased by E. B. McFarlin of San Antonio in 1956. The McFarlin family gave the 49.2 carat stone to the Witte two years later, where it was prominently displayed as the McFarlin diamond.

On June 4, 1968, while the museum was open to the public, a thief smashed the display case and snatched the jewel. One year later, a robber arrested in Kingsville for a different offense confessed to stealing the diamond. He claimed to have sauntered into the Witte carrying a lawn chair and a concealed hammer. The hammer he used to shatter the display case, but the lawn chair had a much more elaborate function. At the sound of the alarm, the exit from the room containing the diamond was blocked by a gate descending from the ceiling—but the thief left the lawn chair in the doorway to keep the gate from dropping all the way to the floor. It worked. Where is the diamond? .In his confession, the thief said he sold it whole to someone from Phoenix for $25,000, of which he received only $6000. The fence supposedly got it out of the country through Chicago. Now, however, he is singing a different tune. Police assume he cut it up into little pieces (greatly reducing its value) and kept it. He’s willing to tell where it is, too—but not unless the feds or the state grant him favors.

The Case of the Missing Millionaire

Robert L. “Tex” Roberts was—perhaps still is—an aging, eccentric, cigar-smoking millionaire. He lived with—and perhaps still lives with—an older female companion, Jessie Forsyth. No one knows precisely what he is doing today because Tex Roberts and Jessie Forsyth vanished mysteriously from his suburban Dallas mansion six years ago and haven’t been seen since. Roberts’ ample fortune has disappeared too—though less mysteriously—and so have two other people, and an attorney has served a prison term, making the Roberts affair one of the most bizarre missing persons cases on record.

It began on the night of August 15, 1970, when Roberts, whose real name wasn’t Roberts—he was born Leroy Sevier—summoned his friend and bodyguard Al Bergeron concerning a matter of “utmost importance.” After finishing some personal business, Bergeron went to the mansion. He found the usually locked front door ajar but no one home. (The independent Roberts kept no servants.) It was not unusual for the 85-year-old Roberts to leave the house suddenly, but it was virtually unprecedented for 89-year-old, infirm Jessie Forsyth to accompany him. After waiting several hours for Roberts to return, Bergeron called the police.

A friend called Bergeron two days later with news of a special delivery letter from Tex, who wrote that he had left the state on business and that attorney Leon C. Horton would be managing his affairs during his absence. Two days after Roberts disappeared, Horton filed deeds to virtually all of Roberts’ real property, including the mansion on Spring Valley Road, at the Dallas County courthouse. The property had been sold to a management company created and owned by Horton. Next Horton tried to cash Roberts’ ample holdings of stocks and bonds. Despite the fact that Horton had a document giving him power of attorney, no Dallas bank would negotiate the transactions. But an Amarillo bank did, and Horton converted the securities into cash, transferring the proceeds into his own commercial accounts. Then Horton withdrew the funds—to send to Tex, the attorney told Bergeron, pursuant to a prearranged plan. Bergeron—who knew he was a major beneficiary under his friend’s will—didn’t quite know what to think about Horton’s assurances that Tex was getting the money. He asked to be put in touch with Tex personally, but Horton insisted on protecting his client’s strict request for secrecy.

Then in January 1971, Bergeron received a Christmas card from Tex which had been mailed from Homer, Louisiana (population 4483), located near the Arkansas border. Other friends had also received similar cards, Bergeron learned—all with the addresses typed. Bergeron looked at the familiar signature again and decided it didn’t look quite right.

Now the bodyguard began to investigate in earnest. He discovered that another elderly woman who had sold real estate to Horton had disappeared in 1969, in an apparently unrelated case. He also consulted a handwriting expert and Paul Chitwood, an attorney who had previously done legal work for Roberts. Chitwood decided a court of inquiry was necessary, and Judge Dee Brown Walker agreed.

The inquiry was hampered from the start when Horton was assaulted in the courthouse parking garage; his briefcase, containing important documents including the original power of attorney, was stolen. Nevertheless, the handwriting expert (using copies) testified that Roberts’ signatures were, in his opinion, not genuine. Horton and Ardis O’Dell Reed, the notary who witnessed Roberts’ signatures, were subsequently indicted for their roles. A Randall County grand jury also indicted the lawyer for converting common stock to his own benefit. He was convicted of theft by false pretext and sentenced to a ten-year prison term, and was later convicted on four counts of forgery in Dallas. Other than Horton himself, no one except Ardis O’Dell Reed may know for certain where Tex Roberts is, but after he was released on $15,000 bond, Ardis O’Dell Reed vanished for over two years. When he finally surfaced, the Dallas DA’s office mysteriously lost interest in the case and agreed to a probated sentence.

The Trail of the Vanished Gems

If you should happen to spot a short, muscular man with a long stride walking down the street with a screwdriver in his hand, wearing cheap rubber rain shoes and surgical gloves and possibly even a handsome piece of jewelry or two, Walter Fannin would like to hear from you. Fannin has been looking for him, unsuccessfully, for almost twenty years. The man in the rain shoes is not Fannin’s long-lost rich uncle (though he is rich); indeed, Fannin doesn’t even know his name. But he would like to. For Fannin is chief of detectives for the Dallas police force and the short, stocky man is the King of Diamonds, the most daring—and most successful—jewel thief ever to operate in Dallas.

From 1956 to 1966 a cat burglar heisted more than $1 million in jewels from palatial homes in north Dallas and the Park Cities. He made “impossible, Topkapi-like entrances through seemingly inaccessible windows and slipped away unobserved on all but one occasion. The list of his victims read like the Dallas social register: James Ling, Clint Murchison, Sr., P. E. Haggerty (then president of Texas Instruments), and at least a dozen others. Each time the thief knew exactly what he was doing. He never cracked a safe but simply lifted the goods from a bathroom dressing table. He took only women’s jewelry—and only the best pieces at that, never costume jewelry and never ordinary items like pearls. On one venture, which netted him $215,000 in stones, the King apparently leaped fifteen feet from a wall to a narrow second-story bathroom window ledge. Even Rudolf Nureyev would have difficulty performing such a feat.

The King reaped so much publicity he became an inspiration for lesser thieves, who attempted to emulate him without success. Arrests were made, some jewels recovered, but the King himself was never caught. All police have is a single description, plus the certain clue that the King must have had close contacts in Dallas society. The search centered for a while on a young gigolo, but the police could prove nothing. The King’s last performance came more than a decade ago, in February 1966, and Fannin now says resignedly of the cases, “They’ll never be solved.”

- More About:

- Crime