This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On a hot June day thirteen years ago, Dominique de Menil flew to Munich to meet a Turkish businessman named Aydin Dikmen who wanted to sell her two Byzantine frescoes. Mrs. de Menil was a charming and elegant woman with a large fortune and social connections that stretched around the globe; Dikmen had a sketchy background, was neither charming nor elegant, and would later figure in a scandalous trial that would capture the attention of the art world. But Mrs. de Menil didn’t know anything about Dikmen at the time, and that afternoon, she and several of her associates piled into two Mercedes that he had arranged for and set off to look at the frescoes. Based on photographs that she had been shown, Mrs. de Menil anticipated that the Turkish businessman was going to show her work of unusually fine quality.

Dikmen led the caravan from the center of Munich to a shabby working-class neighborhood on the edge of the city. The members of Mrs. de Menil’s party were nonplussed by this, as they had expected a more fashionable destination, but Dikmen explained that he was using an address in the neighborhood as a cheap place to store the frescoes temporarily. He then led Mrs. de Menil and the others up a flight of stairs and into an apartment where they encountered an extraordinary scene: The only illumination in the place came from two candles (Dikmen explained that the apartment had no electricity), and by their dim light, the group could make out two segments of plaster, propped against a wall. One featured the image of an angel, and the other depicted John the Baptist. The priceless frescoes had been crudely broken into several dozen pieces—the rest of them were packed in a huge crate. Mrs. de Menil was sickened by what she saw. “The pieces were too much chopped up to derive any impression of beauty,” she said recently. “It was like a miserable human being that has to be brought to the hospital.”

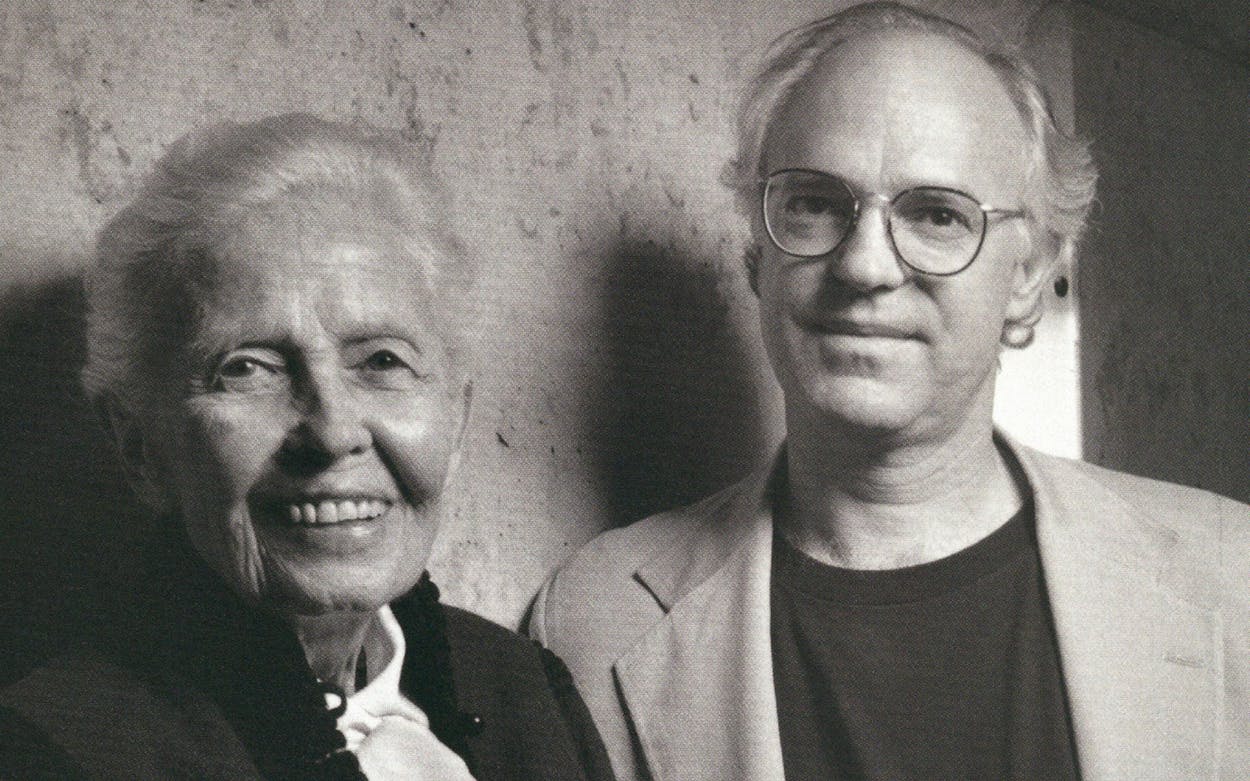

And so she decided to rescue the frescoes. Over the last decade, Mrs. de Menil has subsidized a painstaking restoration of the works, and she commissioned her son, Francois, who is a 51-year-old architect, to design a chapel in Houston to house them. When the Byzantine Fresco Chapel opens to the public in February, she will unveil what is perhaps the most significant example of Byzantine art to be found in this country.

But she doesn’t legally own it. In the months that followed her strange trip to Munich, Mrs. de Menil learned that Dikmen had lied to her about the origin of the frescoes—and that in fact they had been stolen. When she decided to buy them anyway, the issue of where they belonged became a dilemma. Because of the care she has lavished on the frescoes, many people in the art world view Mrs. de Menil as the savior of the works and see no harm in her wish that they remain in Houston. In culturally sensitive times such as these, however, the purchase of another country’s stolen patrimony is a touchy issue, and she has been subjected to an uncomfortable degree of scrutiny from people who believe that the art should be returned to its homeland. Mrs. de Menil, who took care not to break any laws by acquiring the works, deeply resents any criticism of her actions. When asked why she felt it was important that the frescoes remain in Houston, she said, “The Byzantine tradition is a great tradition. You cannot see such an important example of the Byzantine tradition in America or in most parts of Europe.” But while the other parties with a claim to the frescoes have gone along with her wishes for the time being, the question remains: When the moment comes to settle the frescoes’ fate permanently, will everyone agree that Francois’ chapel is their rightful home?

The utter incongruity of that afternoon in Munich—of someone like Dominique de Menil meeting with a fly-by-night character in such a seedy setting—was driven home to me when I visited her at her airy, modern house near Houston’s River Oaks neighborhood in October. Mrs. de Menil is 88 years old, white-haired and fragile, but age has not diminished her strength of character. When we met, she was dressed in a cream silk blouse, black cardigan, checked wool pants, and brown leather sandals with socks, and she eased herself gingerly into one of the chairs in her living room.

Mrs. de Menil was born in Paris into the Schlumberger family, which had built a fortune in the textile business; in the twenties her father, Conrad Schlumberger, invented a tool that tested the contents of newly drilled oil wells, leading the family to amass an even greater fortune. As a child, she collected stamps, matchboxes, and fossils; later on, with her husband, Jean de Menil, a Parisian banker who eventually became an executive with the Schlumberger companies, she began collecting art.

First the couple collected modern art, then they got into African artifacts, and then objects from other parts of the world. “I’m interested in everything,” she told me. “I was born curious.” Most of the art Mrs. de Menil owns (her husband died in 1973) is now housed in the Menil Collection, a stark, minimalist gray building on Sul Ross Street that was designed by Italian architect Renzo Piano. The museum is small, but the work it contains is of international stature.

Although her family was Protestant, Mrs. de Menil converted to Catholicism after her marriage, and eventually she became absorbed in the art of the Eastern Orthodox church of Byzantium. With her purchase—through a London art dealer named Yanni Petsopoulos—of the private collection of a British real estate dealer named Eric Bradley in the early eighties, she became the owner of one of the finest collections of Byzantine art in this country. Highlights of her Byzantine holdings are displayed to the public on the ground floor of the Menil Collection, but the bulk of them is kept upstairs in a locked room, where rows and rows of somber Greek Orthodox icons and colorful Russian Orthodox icons stand on shelves that stretch from floor to ceiling.

The antiquities trade is a shady business in which articles frequently pass through the hands of disreputable middlemen before they wind up in the hands of reputable dealers, and once Mrs. de Menil got into the market for ancient art, it was inevitable that she would be presented with an artifact of questionable provenance. In the spring of 1983, Bertrand Davezac, the curator of antiquities at the Menil Collection, heard that Yanni Petsopoulos had a client who was looking to sell a Byzantine artifact of major significance. Aside from icons, which are commonly found on the market, other Byzantine works are typically part of the architecture of buildings—they are often mosaics or frescoes—and because they are fixed in place, they rarely come up for sale. Davezac was going to Europe in June anyway—he was scheduled to join Mrs. de Menil in Paris to help her take a group of Houston collectors on a museum tour—and it would be easy to include a stop in London. But when Davezac arrived at Petsopoulos’ offices and inquired about the major work that was supposed to be for sale, Petsopoulos did not know what he was talking about. The dealer pointed to an icon of John the Baptist that was hanging on the wall behind him. “You mean this?” he asked.

“Well, that is very beautiful,” Davezac said, “but my understanding was that you had something very out of the ordinary, an object of some kind for which you thought the ideal place would be the Menil Collection.”

“Oh, yes,” said Petsopoulos. “The frescoes that a Turkish collector owns.” The following day, Davezac arrived in Paris with photographs of the Byzantine frescoes that Petsopoulos had passed along. They showed the interior of a tiny medieval church. Painted across its dome was a Byzantine figure of Christ known as a Pantokrator (the ruler of all things) and a ring of angels and saints; painted across its apse was a depiction of the Virgin Mary flanked by two archangels. The photographs were poor, and the frescoes looked as if they had deteriorated with age, but when Davezac showed them to Mrs. de Menil, she was struck by the power of the work. “Fresco is a very difficult art,” she told me. “You paint on fresh plaster, and you have to go fast. So I could see from the photographs that we were dealing with a master. The swing of the drapery, the way the fingers were made, all denoted a master.”

Nothing in Mrs. de Menil’s Byzantine collection approached the significance of the two frescoes, and she immediately arranged to see the objects themselves. They were in Munich, where Aydin Dikmen was living at the time, and Mrs. de Menil and Davezac arrived in the German city the next morning, where they rendezvoused with Walter Hopps, the director of the Menil Collection, and Elsian Cozens, Mrs. de Menil’s longtime assistant. That afternoon, the de Menil contingent met Yanni Petsopoulos in a downtown hotel, where he introduced them to Dikmen, who appeared nervous, as well as to an associate of the Turkish businessman’s whose name nobody can recall. “I expected perhaps to meet a gentleman, probably a classy individual, and then be taken to his house, where he would show us a beautifully displayed piece of Byzantine art,” Davezac told me. “That was extraordinarily naive of me. When we saw those two characters, my heart sank. They looked so seedy. We knew we weren’t dealing with decent people.”

Nobody in the de Menil party spoke any Turkish or German, the only other language that Dikmen knew, so the afternoon’s conversation took place in a cumbersome, convoluted fashion, with Dikmen’s acolyte translating from Turkish into Greek, and Yanni Petsopoulos translating from Greek into English. In this roundabout manner, Dikmen informed the de Menil group that he was in the ship-scrapping business but dealt in antiquities on the side. He also told them that he had found the frescoes when he dug up a little basilica while excavating the site of a new spa in southern Turkey—a story that struck his listeners as improbable.

Although Dikmen presented the de Menil party with an official export permit from the Turkish authorities to back up his claim, they suspected that it was not legitimate. Beyond that, the damage that had been done to the frescoes, the poor light in which they were being shown, and the centuries of dirt and soot that obscured the images rendered the objects far less impressive than Mrs. de Menil had imagined they would be. But at Davezac’s urging, she agreed to pay Dikmen some earnest money (the de Menils won’t say how much) to secure the right to buy the frescoes at some point in the future and arranged to have them sent to London, where experts working for the Menil Collection could inspect them more thoroughly. If the experts were satisfied with their quality, Mrs. de Menil agreed, the Menil Foundation would pay an established sum of money into an escrow account in Switzerland. Again, the de Menils declined to specify the amount.

When Mrs. de Menil returned home to Houston, she immediately got in touch with Herbert Brownell, a New York attorney and former U.S. attorney general, for advice about the legality of buying the frescoes. Brownell responded that the law was uncertain on the subject. Furthermore, he didn’t know whether the laws of Germany, where the objects had been offered for sale, or the laws of the United States, where the Menil Foundation is based, would apply. Finally, while the United Nations had established rules for recovering national treasures, it wasn’t clear whether Dikmen’s frescoes fell into that category.

Deciding to take the most cautious approach possible, Mrs. de Menil asked Brownell to conduct a search for the frescoes’ true owners. Brownell sent a letter to the embassies of nine countries that had once been part of the Byzantine Empire, alerting them to the fact that some ancient frescoes had recently come on the market. “While our clients have no reason to believe that there is any impediment to the purchase of these paintings,” it stated, “given their present location in Western Europe, they feel that the importance and quality of the material is such that it would be appropriate and correct to approach the relevant authorities in all the countries that might be concerned, in order that any possible claims to these paintings could come to light.”

Meanwhile, Davezac began to suspect that the frescoes might be from Cyprus, rather than Turkey, as Dikmen had claimed, because of their clear stylistic parallels to other works from that island. Indeed, when Andreas Jacovides, Cyprus’ ambassador to the United States, got Brownell’s letter, he immediately contacted his government. “We got the reply ‘Hold it, they are from such-and-such a church in the occupied part of the island,’ ” Jacovides remembered in a recent phone conversation. Two other countries—Turkey and Lebanon—also claimed ownership of the frescoes, but only Cyprus was able to back up its claim with documentation.

In the years following Turkey’s invasion of Cyprus in 1974, the art market was flooded with objects torn from the island’s ancient churches and monuments. After Turkey gained control of the northern half of the island, there was widespread looting of cultural works from that region, particularly from Greek Orthodox sites. Many of the robberies were methodically carried out, indicating that international art-theft rings had probably moved into the area. Ambassador Jacovides learned that the frescoes Mrs. de Menil was interested in had been stolen from a small thirteenth-century church near the town of Lysi, in northern Cyprus. Sometime in the late seventies or early eighties, thieves apparently visited the church, cut the frescoes into 38 segments, glued cloth to their surfaces, and ripped the painted plaster from the ceiling in pieces. In other words, the frescoes were war booty.

Once Mrs. de Menil learned that the frescoes had been stolen from Cyprus, she had to decide whether to inform law enforcement officials or deal with the thieves. Because she feared that going to the police might cause Aydin Dikmen to destroy the frescoes or sell off the pieces to different parties to get rid of evidence linking him to the robbery, she decided to make a deal. In the summer of 1983 she entered into protracted negotiations with Cypriot government officials and with His Beatitude Archbishop Chrysostomos, the head of the Church of Cyprus, even visiting the island in person in an effort to gain permission to keep the frescoes in Houston temporarily instead of returning them to their homeland right away. By December of that year, she had obtained the approval of the Cypriot officials to pay Dikmen a sum that she called a “ransom” (when I asked her how much it was, she said she couldn’t remember), even though a final agreement about the frescoes’ fate was still pending. “We faced the difficult decision of whether to say, ‘Wait, it’s stolen property’—in which case we would run the risk of having the frescoes go underground—or making some kind of arrangement,” said Ambassador Jacovides. “It was felt at the time that it would be better, for the sake of preserving the frescoes, to have the arrangement.”

Funds were deposited into the Swiss escrow account that December. The following month, the 38 segments of fresco were transported from Munich to London, where they were stored in a shipping warehouse. Employees of the Menil Foundation examined the segments and had them analyzed to ensure their authenticity. In July Mrs. de Menil had the pieces transported from the warehouse to a rented loft space in London, where she left them in the care of Laurence Morrocco, a leading expert in the restoration of Byzantine art. When Morrocco first saw the frescoes, the cloth that the thieves had glued on them was still attached to many of the pieces. He was able to remove the cloth successfully, but then he had to affix a protective paper covering to prevent damaging the frescoes while he handled them. Because the protective covering obscured the images on the fragments, Morrocco didn’t know whether he had joined the fragments at the right points until he was near the end of the restoration effort, which took almost four years.

“My nightmare was that some of the lines which crossed the saw cuts would not connect perfectly, and the whole rhythm of the painting would be lost,” he wrote in a book about the frescoes that the Menil Foundation has published. “The effect would be like a great violinist playing a fine instrument that was slightly out of tune: Instead of something uplifting, a discord would be created.”

Because northern Cyprus was still a military zone, Morrocco was not able to visit Lysi until he had almost completed the restoration project. His most difficult problem was estimating the shape of the small church’s dome and apse; although the diameter of the dome was relatively easy to calculate, he couldn’t determine its curvature, as most of the fragments had lost their original shape after they were removed, and some were even bent so that they curved the wrong way. Morrocco began by building a dome out of Styrofoam. He then made copies of the fresco segments out of a flexible polyurethane material and reshaped the dome until the polyurethane pieces fit together neatly when placed face down on top of it. Once he had determined the original curvature of the fragments, Morrocco rigged up a steam bath to ease the pieces back into shape. Finally, he made a polyurethane shell that looked like a bowl, and laid the fresco fragments into it. Once they were joined together temporarily, in what he hoped was the correct fashion, he carefully removed the frescoes and applied a strong backing to give them rigidity: First a layer of cotton muslin was attached, then a layer of canvas, then sheets of polyvinyl chloride. Essentially the same process was repeated to assemble the fragments from the church’s apse. The final layer would consist of an extremely strong fiberglass commonly used in the hulls of racing boats.

Before Morrocco applied the layer of fiberglass, however, he was able to arrange a visit to Lysi. He spent several days searching for the church before he finally found it. “It was as if it had just happened,” he wrote of the scene he found inside. “The saw cuts were still visible in the plaster left behind when the fragments were ripped off. I could see how the thieves had cut crudely around the circumference of the base of the dome, leaving the angels’ ankles and feet on the wall. Small pieces of the fresco lay scattered around the floor amidst dirt, straw, and sheep droppings.”

After measuring the church’s interior, Morrocco was horrified to discover that while he had recreated the dome exactly, he had miscalculated the width of the apse: It was fifteen inches less than he had thought. When he returned to London, he had to slowly squeeze his reconstruction together until it conformed to the right dimensions. Now he was ready to remove the frescoes’ protective covering. Special scaffolding had to be built inside the loft to allow Morrocco and his assistants to work on the interior of the dome and the apse. “We worked in sections, gradually loosening the layers of facing paper by wetting the surface with cotton swabs soaked in solvent,” Morrocco wrote. “Masks had to be worn, as the fume buildup inside the dome was considerable.” He was inordinately relieved when it looked as though he had correctly put the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle back together. “[M]iracle of miracles—everything seemed to join up. Even those difficult, almost vertical, lines on the angels’ wings seemed to run smoothly across the saw cuts . . .”

In April 1988, after Morrocco had filled in the cuts and repainted the damaged areas, the frescoes were crated up and flown to Houston. “And then for the first time I saw the frescoes in their totality,” said Mrs. de Menil. “I was not disappointed.”

American regulations concerning stolen art, which were murky when Dominique de Menil acquired the Lysi frescoes, became more explicit after 1989. That year, the Republic of Cyprus successfully sued an inexperienced Indianapolis art dealer named Peg Goldberg to recover some mosaics that had been stolen from the sixth-century church of Panagia Kanakaria in the village of Lythrankomi. Goldberg had bought the mosaics from Aydin Dikmen the year before. Her possession of stolen artifacts had come to the attention of Cypriot government officials after she attempted to sell her mosaics to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu for $20 million—$19 million more than she had paid for them. Cyprus’ subsequent case against Goldberg, which became the subject of a two-part article in The New Yorker, turned on her failure to diligently search for the mosaics’ rightful owners. While Goldberg had contacted several countries to see if the mosaics had been reported stolen, she had neglected to contact the Republic of Cyprus.

Because they had also had dealings with Dikmen, both Mrs. de Menil and Walter Hopps were deposed as part of the lawsuit. During the trial, it became public that Yanni Petsopoulos had tried to sell Dikmen’s two Byzantine frescoes to at least one other party before he ever spoke to Bertrand Davezac. Petsopoulos had approached Gary Vikan, who was then a senior associate at the Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies in Washington, D.C. The dealer had told Vikan, too, that the frescoes—for which he was asking $600,000—had been discovered accidentally at a construction site in Turkey, but Vikan didn’t buy the story. When he was called to the stand during the Goldberg trial, Vikan testified that he had found the frescoes’ documentation questionable and had told Petsopoulos that he wasn’t interested in doing business because he thought the objects being peddled were illicit antiquities. Reached by telephone at the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore, where he is now the director, Vikan explained why he didn’t pursue the deal. “This was archaeological stuff and I didn’t know where it came from,” he said. “It was different from a coin or a ring or an icon, which can wander the world over. This was part of a building, it had come from a certain place, and that place was unknown. That bothered me.”

Although Mrs. de Menil knew a lot about buying art, it seems that, initially at least, she was more gullible than Vikan, as she apparently thought the frescoes had come on the market legitimately when she first heard about them. Nevertheless, according to Tom Kline, an attorney now with the Houston-based law firm of Andrews and Kurth who represented Cyprus in its lawsuit against Peg Goldberg, there is no comparison between Goldberg’s purchase of the Kanakaria mosaics and Dominique de Menil’s purchase of the Lysi frescoes. “It’s night and day,” Kline said recently. “The de Menils always made the assumption that the frescoes were very valuable and could have been stolen, and it seems to me they did everything you would want them to do to find the true owners. Peg Goldberg’s efforts to determine where the Kanakaria mosaics came from were less than thorough.”

To the Greek Cypriot residents of Cyprus, the most disturbing thing about the looting of their island that took place after the Turkish invasion was the religious nature of the objects that were stolen; they believed that the artwork possessed spiritual powers. As Dan Hofstedter wrote in The New Yorker, icons were “traditional vehicles of contact with the Almighty.” For Greek Cypriot officials, the question of whether they would be able to recover objects stolen from their island once they appeared on the market was therefore a particularly sensitive one. According to the final agreement between the Menil Foundation and the Church of Cyprus, which was not signed until 1987, Mrs. de Menil does not legally own the frescoes, as one cannot obtain good title to a work of art that has been stolen. Instead, she acquired the frescoes on behalf of the Church of Cyprus, which retains its original claim to them. But Mrs. de Menil succeeded in persuading the church to allow the frescoes to reside in Houston—where the Menil Foundation would display them in a chapel consecrated as an Eastern Orthodox church—for an established period of time. The de Menils hope the chapel will be used by Houston’s sizable Greek immigrant community. “It’s much more a religious approach than a museum approach,” Mrs. de Menil explained. “A religious object in a museum loses its function. It becomes an object. So the principle I’ve applied is to restore religious art to its function.” After a lapse of twenty years, a period that began on January 1, 1992, the frescoes’ fate will be revisited. In other words, the question of whether the frescoes will return to Cyprus remains open. And the de Menils hope that returning them will not be necessary. “I think by that time the frescoes will have become part of the fabric of Houston,” said Francois. “We would want to keep them here, as long as the Church of Cyprus is willing.” The agreement also stipulates that the building and the land be deeded to the Church of Cyprus for as long as the frescoes are there. “So in a way it is as if the frescoes are on Cypriot soil,” Francois said.

Experts in Byzantine art take the view that Mrs. de Menil did a great service in purchasing the frescoes because it seems unlikely that otherwise the segments would ever have been reunited with such skill. “I can imagine fifteen pieces spread out in fifteen houses all across France and England and Germany,” said Gary Vikan. “I can imagine someone buying them lock, stock, and barrel, and then putting them in a barn for fifty years. Or buying them and putting them back together poorly.” According to Dan Hofstedter, however, the agreement between the Menil Foundation and the Church of Cyprus was viewed bitterly by some people in Cyprus. “A Cypriot civil servant who had negotiated with the Menil [Foundation] told me that ‘the dynamics of the conversations’ had left him with the feeling of ‘blackmail,’ ” he wrote in The New Yorker. “If Cyprus didn’t cave in to the Menil’s self-serving proposal, he felt, the foundation would pull out altogether, leaving the frescoes to their fate.”

Apparently the representatives of the Menil Foundation did convey some sense of threat during their talks, but it is possible that that was a mistake on their part rather than a deliberate tactic. “My impression is that the threats were coming from the smugglers and were simply passed on by the de Menils,” said attorney Tom Kline. “But maybe Cyprus didn’t know what was coming from the de Menils and what was coming from the smugglers.” Today, at any rate, the government of Cyprus clearly supports the construction of the chapel in Houston. Several Cypriot officials, including Ambassador Jacovides (along with Houston Rockets superstar Hakeem Olajuwon), now sit on the board of the Byzantine Fresco Foundation, which was formed to oversee the chapel’s finances and administration. The Cypriot government officials’ current goodwill may owe something to a favor the Menil group performed. While negotiations over the fate of the Lysi frescoes were still in progress, they served as intermediaries between Cypriot officials and Aydin Dikmen in an effort to recover additional stolen Cypriot artwork from the Turkish dealer. Dikmen had sold Peg Goldberg only some of the Kanakaria mosaics he possessed, and the Menil staff worked with Constantine Leventis, a wealthy philanthropist and the Republic of Cyprus’ ambassador to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, to force Dikmen to return two other sections of mosaic by refusing to release the money that had been put in the escrow account until he cooperated. “I believe that Constantine Leventis exerted some influence to slow down the transaction regarding the Lysi frescoes, and the de Menils helped him with that,” said Tom Kline. “I think it’s fair to say they assisted Constantine Leventis in getting some of the mosaics back.” In her deposition for the Goldberg case, Mrs. de Menil also said that the Menil Foundation paid to transport the mosaics back to Cyprus.

By 1988 the Lysi frescoes had been fully restored and the negotiations with Cyprus had been completed, but because the project had strained the finances of the Menil Foundation, work on the chapel in Houston did not begin until 1995. (The acquisition and restoration of the frescoes, as well as the design and construction of the new chapel, have added up to more than $5 million.) In the meantime the frescoes were stored in the basement of the Menil Collection, a situation that apparently displeased His Beatitude Archbishop Chrysostomos of the Church of Cyprus. Archbishop Chrysostomos has his own museum in Nicosia, where the Kanakaria mosaics recovered from Goldberg and Dikmen now reside, and he probably felt that the Lysi frescoes belonged there as well, if they weren’t going to be put in a chapel in Houston as had been agreed. However, the archbishop’s concerns were apparently assuaged once the de Menils threw their energies into completing the project, which was facilitated by a large fund-raising effort, and he is expected to preside over the consecration of the chapel in May. Said Tom Kline: “Whatever bad feelings may have existed seem to have dissipated now that it’s clear they’re doing something that’s going to be world-class.”

The Byzantine Fresco Chapel is located at the corner of Branard and Yupon streets, a few blocks from the Menil Collection. The project has been the subject of a lot of talk in Houston, primarily because Mrs. de Menil kept the job in the family. “It’s a great way to make your son famous,” carped one local architect. “I wish my mother had that kind of money.” But the chapel has already won two architectural awards. Francois de Menil’s building is an attractive mélange of blue-gray stone, gray slabs of cast concrete, and a dark, pewter-colored metal. (The building’s exterior blends in with the Menil Collection and the surrounding houses, which are all painted a distinctive dark gray.) Initially, a London firm had designed a structure that was a replica of the church near Lysi, but Francois and others convinced his mother that putting a copy of a thirteenth-century building in the middle of modern-day Houston was not the right approach. “My son showed me that I was well on the way to building another Disneyland,” Mrs. de Menil said. “Next time I would build a little pagoda to present some Chinese relics.” Francois’ design refers to the Lysi chapel but does not attempt to replicate it. Inside a main hall that encloses a steel box, large translucent panels of glass are arranged in the outline of the little chapel. The glass panels don’t quite touch; Francois wants the broken outline to suggest the desecration that occurred in Lysi while simultaneously resurrecting the shape of the original building.

After touring the unfinished chapel with Francois, we went over to Richmond Hall, a part of the Menil Collection complex where the restored frescoes have been housed for the past year. The dome was standing face down on the floor, and Francois and several contractors were deciding what kind of black paint to use on the back of its fiberglass shell. The apse stood behind the dome, a thick plastic curtain taped over its front. It was frustrating to get so close to the frescoes and still be unable to view them, and I was wondering if I could ask to see them when one of the contractors suggested that we pull aside the plastic curtain covering the apse. Against a deep blue background, the Virgin Mary was painted in reds and browns and paler ocher colors. The work, which had an earthy quality, was riddled with ancient cracks and seams (while Morrocco had repaired the damage done by the thieves, he did not disguise the damage done by time). The Virgin’s face bore an expression of quiet serenity; her arms were spread out in welcome, and a veil was draped around her shoulders. According to Annemarie Weyl Carr, an art history professor at Southern Methodist University, Byzantine legend holds that the Virgin’s veil carries mysterious powers of protection—when carried into war, it is supposed to have thrown enemy armies into confusion.

In late November the apse and the dome were brought into the chapel and huge cranes and pulleys built into the structure were used to raise them into place over the glass panels. Francois’ gray-and-black chapel embraces the frescoes, and their vibrant colors and liveliness should leap out at viewers.

On February 8 the chapel will be formally opened to the public. Just inside the entrance, a panel of text will explain the story of how the frescoes came to be in Houston. “It’s an unusual building, and it’s an unusual circumstance,” said Francois. “You could just walk in and look at the frescoes, but we think it’s important to know the story—to understand the rape and the rescue of the frescoes.”

- More About:

- Art

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston