Shimofuri is a Japanese word with several translations. One of them is “a layer of winter frost,” which is what Wagyu beef producers in Japan mean when they describe the color of highly marbled Wagyu. The red color we associate with American beef is dimmed by the abundant white fat of Wagyu, which turns a cut of steak lighter shades of pink as the percentage of fat increases. This is what American Wagyu producers are chasing as they try to pair Japanese genetics with American feeding programs to achieve beef that could grade far above USDA prime. G Five Cattle & Meats in Sulphur Springs is doing it better than any Texas Wagyu producer I’ve tried.

Last month, I pulled up to the gravel parking lot of G Five’s retail shop along the Interstate 30 service road. The metal building sits on the south side of the highway, ten minutes west of the East Texas town of Sulphur Springs. While most customers order their G Five steaks online, it’s at the storefront where you’ll see the beef displayed behind the glass doors of freezer cabinets that line the side wall.

The steaks are shrink-wrapped and separated into full-blood Wagyu beef and a crossbreed of Wagyu and Angus. The full-blood Wagyu includes a “reserve” section for beef with an exceptionally high marbling score. Of all the Wagyu I’ve been able to purchase from Texas producers, I’ve never seen a cut so highly marbled. I decided to go home with a thick New York strip steak despite its high price of $82.25.

With so much marbling, more fat drips, so it’s best to keep half of your grill free of coals as a safe zone to move the meat to if flare-ups occur. Mine came out a perfect medium-rare. I served it in quarter-inch slices and shared with friends. The rich, fatty beef is more satiating than most American beef, so a twenty-ounce steak was enough for four of us to feel satisfied. I wanted to order more, and decided to talk with G Five’s founder, Marvin Garrett.

Garrett retired as an engineer in Louisiana before moving to East Texas on land he purchased in 2007. In 2012 he decided to raise some Angus cattle. He had only cows, so he had them artificially inseminated (AI) with the genetics of an Angus bull. A few years into the operation, he heard about the Wagyu breed, and used those genetics for the AI process. Once those F1 crossbred cattle reached maturity, he had one processed for his home freezer. As Garrett describes on his website, it was “the best beef I ever had.” By 2016 he had bought his own black Wagyu bulls, and began developing the traits that are now showing up in his cattle.

The G Five herd is currently around 550 head. That includes Angus, full-blood black Wagyu cattle, and crossbreeds on the Sulphur Springs ranch and at Schechinger Farms, Garrett’s preferred feedlot in western Iowa. He sends most of his F1 cattle there to fatten them before harvesting, but far fewer of the full-blood Wagyu cattle, which are fed for at least a year, get the same fate. He keeps most of the heifers and the most-promising-looking bulls to grow the herd. That means over the last three months, G Five has had only seven head of full-blood Wagyu processed for the store, and thirteen of the F1. That’s not enough to be a reliable supplier to steakhouses, but that’s the goal. “We want to get into boxed beef, selling to restaurants and meat markets, if I can get a fair price for it,” Garrett said.

For now, Garrett’s excited about the recent jump in marbling. “The quality has gone up significantly in the last two years, and specifically this year,” he said. All the beef is processed at BRK Meats in Carthage, and Garrett bought them the same MIJ camera the Japanese use to measure the intramuscular fat percentage in their Wagyu beef. (Iron Table Wagyu uses the same technology.) Among other data points, the camera calculates a beef marbling score (BMS) from 1 to 12, which is the foundation for beef grading in Japan. The BMS for Japanese cattle that grade as A5 ranges from 8 to 12. Prime grade is the highest in the U.S., which would be roughly equivalent to a BMS of 4 or 5. Over the last twenty carcasses G Five has received from its processor, the average BMS is a staggering 9.2 (up from 7.25 in 2022).

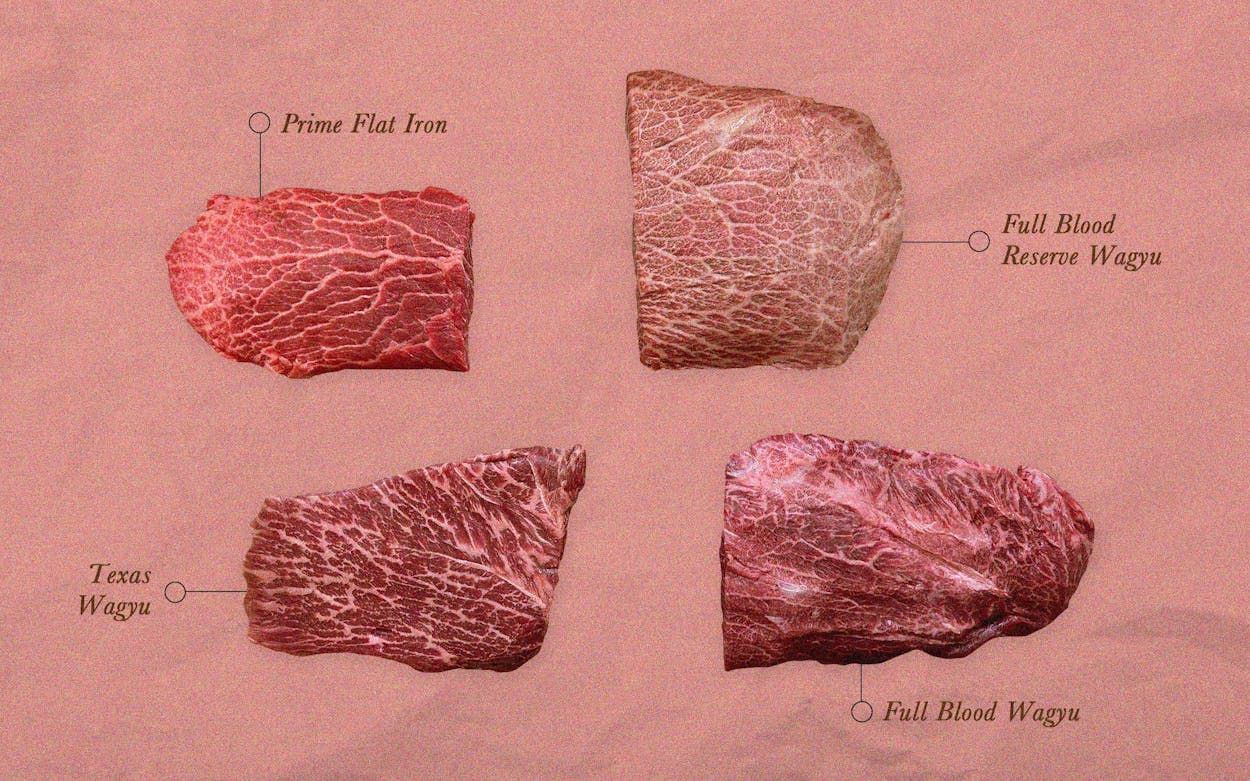

As the high BMS scores became more consistent, Garrett felt it was time to create a “reserve” designation for any of the full-blood Wagyu beef with a BMS of 9 or higher. G Five had just implemented the reserve program days before I walked in. Garrett’s daughter, Dana, was so proud of a BMS 12 carcass that had just been delivered that she fetched several cuts from the deep freezer to display for me. A few weeks later, I asked Garrett his opinion on a cut that would show off the reserve beef well, and he suggested a flat iron. I ordered three: one reserve ($56.50 per pound), the other a full-blood Wagyu ($46 per pound), and another Wagyu-Angus crossbreed that G Five labels Texas Wagyu ($35 per pound). I grilled them all at home to taste alongside an all-natural prime-grade flat iron from Central Market.

G Five’s Texas Wagyu was visually similar to the prime flat iron. It seemed more tender, but that could have been bias on my part since I knew what I was eating. The full-blood Wagyu was much more juicy from the additional fat, and the flecks of marbling were finer than in the other two. Then came the reserve flat iron. The marbling was so fine and abundant, it was as if a regular steak was wearing a veil. Each slice was intensely buttery as the rich flavor of the fat dominated the beefy notes. It was a hugely different eating experience from the rest.

My apologies in advance, but G Five does not yet have a huge supply of this beef, and it will sell out quickly. Garrett said the beef he’s selling now is proof his methods are working, but it takes time to replicate success. “You make a change, and you don’t realize the results until two or three years later,” Garrett explained. From what I’ve tasted, I can at least say G Five has the right formula to show Texans how good Wagyu beef can be.

- More About:

- The Wild West of Wagyu

- Steak

- Sulphur Springs